The history of contemporary letters has, to a very manifest extent, been written in such magazines.

▸ Ezra Pound, “Small Magazines”

The history of literary movements is more often written in some long forgotten dead little magazine.

▸ Lewis Nkosi, “On Okyeame”

I

LITTLE MAGAZINES MADE literary history in the twentieth century. On that point, Lewis Nkosi and Ezra Pound would agree. But if you begin to ask for more specific details—whose history? what literature? which magazines?—these two would necessarily part ways. When Pound was writing his brief history of “the small magazine,” he had in mind an Anglo-American high modernism made in the pages of

Others, the

Egoist, the

Little Review, the

Criterion, and the

Dial in the 1910s and into the 1920s.

1 Nkosi, who made this observation in a review of

Okyeame, a little magazine published in Ghana in the 1960s, was referring more generally to modern African literature published after 1950.

2 Same medium, different time and place: modern but not necessarily modernist. And in both cases, the little magazine functioned as a world form, a place where writers, readers, critics, and translators could imagine themselves as part of a global community that consisted of, but was not cordoned off by, national boundaries.

And yet you begin to wonder if that’s all there really is to this story of the little magazine: European, British, and American modernists and avant-gardists using the medium to house and exhibit their literary experiments, and postcolonial writers adapting it in the second half of the century to accommodate the rise of independent, national literatures. This particular spin on the little magazine’s transmission ends up making Anglo-European modernism responsible on some level for the birth of modern literature in places like Africa, the West Indies, South Asia, and the Pacific Rim, which is to radically oversimplify and misrepresent the issue. The form of the little magazine, so often identified with modernism, does not, as I’ve already discussed in the introduction, belong only to England, the United States, and Europe, even if it was the vehicle that carried so many modernist texts to readers in and between them. When the little magazine comes to West Africa in the 1950s, for example, it owes as much to the legacy of Anglo-American and European avant-garde and modernist magazines as it does to an expansive network of Lusophone and Francophone newspapers and periodicals that had ballooned in the 1940s along with a lively pamphlet culture transported from India by African soldiers after World War II.

3 The African little magazine, in particular, is a strange amalgam of print media (newspapers, pamphlets, academic periodicals), something that could only emerge in the postwar conditions when independent nations were being born out of the wreckage of collapsed empires and a modernist magazine culture that was already a thing of the past.

4Though critics regularly make this connection between modernist and postcolonial little magazines, it is never given much scrutiny, treated more as an obvious historical fact than a problematic possibility that didn’t necessarily have to happen. What gets lost along the way is any sense that the two actually shared a common, if vexed, past, and when read diachronically, it can change our perspective on the print cultures of modernism and postcolonialism in some unexpected ways. Debates about the relationship between the two have tended to focus on questions of influence, genre, language, style, and technique, with some critics emphasizing the creative appropriations and others the deliberate breaks. For more than half a century, in fact, modernism itself was regularly identified with a Eurocentrism bolstered by the institutions and ideologies of colonialism that postcolonial writers could subsequently expose and attack.

5 As a result, there was considerably less interest in the continuities between them, and there remained a great deal of suspicion about modernism’s productive influence on the development of postcolonial literature in the decades after World War II.

More recently, however, critics such as Neil Lazarus, Jahan Ramazani, Peter Kalliney, and Simon Gikandi have provided new ways to frame this relationship, acknowledging the adversity but also tracing lines of connectivity and commonality that enable us to read modernism through the postcolonial and vice versa.

6 Lazarus, in particular, has argued that in postcolonial critics’ effort to break with Euromodernism, they have, in fact, gone too far and ended up ignoring a critical, anticolonial dimension that he identifies explicitly with “modernist protocols and procedures” employed by contemporary writers (not all of them postcolonial). The little magazine, I would add, is one of the “protocols and procedures” that has been repeatedly ignored by modernist and postcolonial critics alike, in large part because both groups prefer to treat 1945 as a convenient, if problematic, dividing line. For this reason, the modernist and postcolonial magazines have been unnecessarily cut off from one another even if, as I argue, the postcolonial mobilization of this medium in the West Indies and Africa allowed for the radical reconsideration of what the little magazine was to Euromodernism and what it could mean afterward.

What follows is an attempt to read modernism and postcolonialism against each other through the medium of the magazine. To do so, I focus on the little magazine both as a set of media procedures used by postcolonial writers for literary transmission and as a material object designed to function within a transnational literary field that emerged in colonial and postcolonial countries after World War II. This chapter takes seriously the idea that publishing in little magazines in these postwar years was an activity associated with an established and, for many colonial countries, inherited Euromodernist tradition. And while Gikandi has made the bold claim that postcolonial literature “would perhaps not exist” without modernism (citing the establishment of colonial schools and universities consuming the English literary canon), I would add further that it would not exist without the historically validated material practice of publishing

like a modernist.7 Not everyone, of course, wanted to be like Pound or Eliot, but for a poet like Christopher Okigbo, whom I discuss at the end of this chapter, it was impossible to ignore the fact that their greatness was first glimpsed in the pages of little magazines published in England, Europe, and the United States.

Transition, where Okigbo first brought out so many of his poems, was quite different from the

transition that preceded it by a few decades, but as I explain, the sheer variety of structural differences within this and so many other postcolonial little magazines indicates just how malleable the form could be as it moved beyond Western metropolitan centers after modernism and how the arrangement of everything from the contents and cover design to the presence or absence of book reviews, correspondence, distribution lists, and editorial blurbs reflects the complicated process by which this medium negotiated local, regional literary production and the emergence of a global literary field in modernism’s wake.

The postcolonial little magazine isn’t just one more category to add to the mix of immobile, exiled, anti-Fascist little magazines or an afterthought in modernism’s genealogy. It challenges some of the most basic assumptions that have been in place for so long to describe how the little magazine was made to function in the world throughout the rest of the twentieth century. In previous chapters, I’ve exposed some of the myths about transatlantic mobility and the harsh, though productive, realities of homelessness and exile, but in this instance, I’m interested in the fact that the postcolonial magazines had to deal with circumstances that their Euromodernist counterparts did not. And not all of them were alike. They developed in countries such as Trinidad, Jamaica, Barbados, Martinique, Nigeria, and Uganda, each one of them with unique political, economic, and social situations, literary histories, and print institutions and cultures. Together, however, they managed to transform the little magazine into a medium that could consolidate national and regional literatures while also constructing transnational networks capable of catering to a widely dispersed diasporic readership.

Before any comparative analysis of postcolonial and modernist magazines is even possible, we need to enlarge the geography and expand the timeline. It’s a step, in fact, that requires adjusting a narrative about the rise and fall of little magazines that has been in place for almost a century: born on or around 1910 during Ford Madox Ford’s brief reign as editor of the English Review (1908-1909) or the founding of Harriet Monroe’s Poetry (1912), Harriet Shaw Weaver’s the Egoist (1914), and Margaret Anderson’s the Little Review (1914), reaching middle age in the 1920s with the Dial, the Criterion, the transatlantic review, and transition, and taking its last gasp in the late 1930s with the closing of the Criterion and the NRF. Accurate to a degree, this tale is, finally, partial, incomplete, and misleading. What do you do with La revue indigène (1927) in Haiti, Vöörslag (1926) and Drum (1951) in South Africa, Trinidad (1929) and the Beacon (1931) in Trinidad, Tropiques (1941) in Martinique, Kyk-over-al (1945) in Guyana, Bim (1942) in Barbados, Focus (1943) in Jamaica, Black Orpheus (1957) in Nigeria, Transition (1961) in Uganda, and Okyeame (1961) in Ghana?

Here we have a dozen little magazines outside the usual transatlantic or trans-European orbit, and this is only a tiny fraction of the titles and places they were published. They appeared during the rise and, in some cases, after the fall of the Euromodernist little magazine, and none of them were actually plugged into this network. In most cases, they flew under the radar, some of them becoming part of an emerging flood of Francophone and Anglophone magazines crossing and recrossing the Atlantic, others remaining stubbornly anchored in their town, province, or nation (sometimes voluntarily, other times involuntarily). And perhaps that’s why they have been so easily excluded from view. They have nothing explicitly to do with the production or reception of European modernism (western, eastern, or central), many of them belonging instead to that pile of “long forgotten dead little magazines” that Nkosi first identified back in the mid-1960s.

A medium-based history, however, brings modernism and postcolonialism together, not because they circulated the same texts or writers but because they encouraged similar literary and critical practices. In fact, it’s interesting to discover how familiar the origin narratives are for both. Take, for instance, Malcolm Bradbury and James McFarlane’s classic account in

Modernism: A Guide to European Literature, 1890-1930: “It was largely through such magazines that the evolving works of modernism achieved their transmission, sought out their audiences, as

Ulysses did through the American

Little Review. And, gradually, it was the selfconsciously small paper, in an era of large publishing ventures, that began to take over not only the localized work of particular movements but the larger tasks of cultural transmission.”

8 Now compare it with a statement in 1950 by A. J. Seymour, editor at

Kyk-over-al (Trinidad, 1945-1961), which refers specifically to the West Indies but will get modified by later critics writing about Africa: “It is difficult to over-estimate the importance of the Little Reviews appearing in the West Indies because they have been and still are the nursery of literature.”

9 At the most basic level, this repetition suggests that the framework used to describe modernist literature can easily be emptied out and recycled for its postcolonial successor. In Seymour’s account, the “Little Reviews” (still capitalized and kept in the plural), which once named a specific modernist magazine, have become a generic signifier for the medium itself in the postwar, and soon postcolonial, period. This slip reveals a connection, but one that has been deflated. For as much as Seymour wanted to suggest at the time that West Indian writers were repeating history, it was, in fact, a history that remained to be written, making the “Little Reviews” in the West Indies more like nurseries than museums. Seymour, it turns out, was on to something here; but subsequent critics didn’t pick up on the modernist magazines’ postcolonial legacy, and it didn’t inspire much critical reflection on the pronounced differences between the two.

II

While the little magazine in Europe, England, and the United States developed in response to an increasingly commercialized literary culture, in the West Indies and Africa, it was in response to colonialism and decolonization. These contexts, in fact, generated one of the most striking differences between little magazines in the “West” and those in the West Indies and Africa. The little magazine may have played a significant role in the realization of modernism’s larger cosmopolitan project, which involved the emphasis on a denationalized internationalism, but just the opposite was true for the postcolonial magazines: they helped to generate national and regional literary fields, which, instead of being isolated from one another, actually fostered transnational linkages that had never existed before.

10Little magazines published in the West Indies and Africa fostered the kinds of literary and critical affiliations that would end up reinforcing their status as both national, regional

and international, cosmopolitan. It was an association that editors and reviewers attributed to the rise of a global book business firmly anchored in modernism’s metropolitan centers (London, New York, and Paris). One reviewer in

Black Orpheus (1964), for instance, pointed out that magazines like

Bim (Barbados) and

Présence africaine (Dakar) were “reservoirs for Afro-Caribbean literature” precisely because they published “a great deal of indigenous writing that might otherwise never be printed in English, French, and American journals which demand a kind of compromise from their overseas contributors in order to make their material suitable for their own readers.”

11 For A. J. Seymour, whom I just mentioned, the so-called third-world magazine was a repository for the “values of the past” with the power to guide African and West Indian writing in the future.

12 And for Emilio Rodriguez, a reviewer at

Bim, little magazines were an antidote to the exclusionary practices of “metropolitan publishing houses,” allowing for the preservation of a “national linguistic expression” that would otherwise have been lost.

13 Indeed, the little magazine’s impact on the emergence of global literary production often came from its isolation, and these various testimonies articulate the strange paradox that the formation of national languages and literatures within this medium actually required occupying a position on the margins of the system free from the burden of ever having to pass through a Western metropolis for validation.

The

Beacon, which appeared irregularly in Trinidad between 1931 and 1933 (thirty issues in all), was one of the places where it all began, intended to counteract the demoralizing effects of the West Indian magazines where, as Albert Gomes put it, “immaturity assumes concrete form.”

14 In this context, “immaturity” was synonymous with a lack of originality and reflected, in Gomes words, “what slaves we still are to English culture and tradition.”

15 And at a time when magazines like

transition and the

Criterion were busy catering to an established modernist tradition on the other side of the Atlantic, the

Beacon was designed to take on the role of cultural agitator. In this case, however, the target for this agitation was more explicitly a foreign British empire that had effectively controlled literary production up until that point through both its ownership of the machinery and the dominance of its literary models. Writers like Gomes, C. L. R. James, and George Mendes contributed prose fiction to the

Beacon, interspersed with more politically explosive essays about colonialism in East India and Africa, which repeatedly offended the Catholic Church, the British government, and the indigenous middle-class elite and often ended in boycotts, bans, and seizures.

16The

Beacon was an early example of what soon became the more common practice of adapting the little magazine as an anticolonial device. And all of the qualities associated with the littleness of modernist magazines in the West were getting modified to accommodate the development of a modern Anglophone literature in the Caribbean. All too often this relationship between modernism and the formation of postcolonial literatures gets read as a process of subversion taking place within, through, and against European high-modernist styles, languages, conventions, and genres, but what gets repeatedly ignored is the presence of medium itself as both a concrete and a symbolic form for literary and critical transmission.

17 So many of these newly emerging writers from the West Indies were not just working through imported, modernist models they were using the same medium to do so, and I want to emphasize that the very idea of any anticolonial subversion came to involve a simple strategy for publication. To publish in a little magazine in the 1930s, ’40s, or ’50s was to be part of a tradition that was already tried and tested, complete with a long list of underdogs who had managed to make their mark. In this context, however, littleness was associated, consciously or not, with the reality of writing as a subject living under foreign domination instead of voluntary exile, and it identified as much a connection with this Euromodernist tradition as it did a marked departure.

Consider, for example, one of the few explicit references to the little magazine tradition as it appeared in an editorial from

Kyk-over-al (1950): “Traditionally the little review in Europe has been the vehicle for experimental writing and free expression of criticism without concession to the convention of commerce. In Britain, there has been a recent island outcrop of periodicals displaying literature and the arts on a regional basis (e.g. Wales, Scotland and even a smaller unit such as the Reading area of England), and at the same time making available the best ideas from outside the area. In the West Indies also the little review has begun to express West Indian culture.” Here’s another one thirteen years later in

Transition: “And so the small American magazines, which were the first publishers of Hemingway, Faulkner, Frost, Pound, Eliot, William Carlos Williams, Katherine Anne Porter—and, in fact, an estimated 80 percent of all American writers of any literary stature since 1912—have been run out of the pocketbooks, if not the sheer nerve of their editors.”

18 Many people have heard some version of this story before, but when it gets spun in

Kyk-over-al or

Transition, the moral is different. These little magazines in Europe, America, and Britain, now part of a tradition, have become something to emulate, and magazine editors living in colonies on both sides of the Atlantic were beginning to wonder if the process could be repeated under radically different historical, political, and economic conditions, in island outcrops instead of urban centers.

Unlike genres, styles, or even literary techniques, however, the little magazine didn’t have any single national origin precisely because it had already been adapted by so many different cultures in such a short period of time. Still, if it was going to be identified with a European, British, or American modernist tradition (to use the locations identified earlier), it did not have to be pinned down to a specific place, and I suspect that this was why the little magazine was so readily adaptable in such an uncritical way in the decades that followed. Writers living in colonized countries, so many of them barred from a book industry abroad and frustrated by the absence of one at home, used the little magazine as their own: it was a resource capable of providing them with an opportunity to generate an independent literary field.

Bim (1941) in Barbados and

Kyk-over-al (1945) in Trinidad are frequently identified as two of the most successful examples of this process in the West Indies, both of them starting out as isolated island ventures before expanding outward to embrace the entire region and eventually coming to define a West Indian literature that included writers such as Sam Selvon, George Lamming, Edward Kamau Braithwaite, Andrew Salkey, V. S. Naipaul, Derek Walcott, and Roger Mais.

19“Regional cradles” is the term Reinhard Sander employs to describe

Bim and

Kyk-over-al.20 They nurtured new writing, of course, but the term also describes the fact that they were at a crossroads in the Caribbean, each of them bringing together writers, isolated in the past, who began to imagine the possibility of a collective literary future.

Bim, once referred to as “an oasis in that lonely desert of mass indifference,” was the earliest and longest lasting of them all, and it started out, modestly enough, as an alternative to the periodicals sponsored by the conservative, and by all accounts dull, literary clubs.

21 It didn’t take long before

Bim was transformed from an “island magazine,” as George Lamming remembers it, to “a regional magazine,” and this shift was made possible by the fact that writers from around the archipelago were beginning to circulate their work more than ever before.

22 By 1948, when the Montego Bay Conference was held to discuss the possibility of a West Indian Federation,

Bim was already seven years old, and it served the following year as a platform for the

Caribbean Quarterly, an academic periodical sponsored by the recently founded University College, West Indies, in Jamaica.

The 1940s were a pivotal decade in the history of Anglophone West Indian literature. For the first time, a small network of independent magazines worked together to connect writers on the various islands, all beginning to imagine themselves serving the same literary, and quite possibly political, future. The mass exodus of so many West Indian novelists to London in the 1950s, however, has effectively obscured the fact that these magazines continued to exist, sharing writers and critics and often reviewing one another in an act of regional solidarity. Though the

Beacon folded shortly after James and Mendes went abroad in 1932,

Bim and

Kyk-over-al kept on running, the former bringing out issues until 1961 (five years before Guyanese independence), the latter making it all the way to 1981. I bring up the fact of their longevity in order to emphasize that mass migration to the metropolis actually ended up having a positive effect on the Caribbean magazine scene. Not only did writers such as Lamming, Selvon, Salkey, Naipaul, and Braithwaite continue to publish pieces back home, but their positive critical reception abroad effectively brought their native countries into the metropolitan spotlight. So if, as Simon Gikandi contends, the condition of exile was the “ground zero of West Indian literature,” generating a nationalist identity and fanning the desire for decolonization, it was the little magazine that played a formative role in the articulation of any independent literary and political program, opening up its pages to discussions regarding a West Indian identity that was being realized as much through literary production as it was through political action (the shortlived West Indian Federation being the primary example, 1958-1962).

23The BBC’s

Caribbean Voices program facilitated this transatlantic exchange between London and the West Indies, bringing together exiled writers, who would read from their work, with critics reviewing the latest publications.

24 The little magazines where so many of them first got their start weren’t forgotten in the process:

Bim, for instance, would frequently publish work that was already broadcast, sometimes even choosing to pass along original material straight to the radio. At the same time, Frank Collymore would communicate regularly with BBC programmers about the selection of material, and on one occasion, Henry Swanzy, the producer, scheduled a reading from Derek Walcott so that it would coincide with a review of

Bim,

Focus, and

Kyk-over-al because he knew that audiences across the Caribbean “would be turning on their radios.”

25 For writers and editors back in the Caribbean, there may have been a legitimate fear that a radio program of this stature, one produced in London no less, could put an end to the little magazine, but it never did. And as Gail Low has recently discovered in her work in the BBC archives, the eradication of this print outlet was never the intention. Swanzy was particularly sensitive about undermining the influence of little magazines in the Caribbean, occasionally offering to review issues of

Focus, Bim, and

Kyk-over-al in order to reaffirm the idea that the BBC’s “‘main purpose’ was to stimulate West Indian writing in the West Indies.”

26West Indian writing

in the West Indies: that may be true, but it was not always writing

for the West Indies. The gradual move from a more local literature organized by island to a regional one organized by archipelago eventually led to an international one organized along the shadow lines of a diaspora that led all the way back to Anglophone West Africa. That, in fact, was one of the ways that the West Indian little magazine continued to maintain its relevance over the decades: after helping to regionalize West Indian literature, it established links with a West African literary scene that exploded in the 1960s and came to include Gabriel Okara, Wole Soyinka, Christopher Okigbo, Chinua Achebe, J. P. Clark, and D. O. Fagunwa. Already by 1957, when the first issue of

Black Orpheus appeared in Nigeria, a new narrative of the little magazine was being written, and it was one that involved a celebrated cast of West Indian

isolatoes, first nurtured in regional cradles like

Bim and

Kyk-over-al, who then managed to prove themselves on an international stage, putting the West Indies on the map of a much expanded British literary scene.

27Based on the success of these

isolatoes, it’s no surprise to discover that many of them helped launch this awakening of Anglophone literature in West Africa. In the first three years and seven issues of

Black Orpheus, during what Bernth Lindfors has called its “West Indian infancy,” writers from this region dominated the pages, contributing eighteen of the twenty-six poems and six of the ten short stories and serving as the subject for twelve of the sixteen essays (including those devoted to French West African poets and novelists).

28 With numbers like these, it’s safe to conclude that Anglophone Africa was looking westward during this early period, and a magazine like

Black Orpheus was more than heartened by the fact that so many West Indian writers, all of them raised in colonized countries, had created a new literature that was nationally, regionally, and internationally relevant. Indeed, it was a fate that awaited this new generation of West (and soon East) African writers as well, one that makes it impossible for us to ignore how far the little magazine traveled since the days of its infancy in the United States, England, and across Europe, stubbornly refusing to die out even if so many individual titles found it impossible to stay alive.

III

When the little magazine arrived in West and East Africa, the issue of readership and distribution was complicated immediately. Transport and communications technologies were lagging far behind those connecting London, Paris, and New York, making the most basic movement of people, print, and paper from region to region difficult, costly, and time-consuming. Sure, there was an infrastructure that British, French, and Belgian empires helped to create, but with the independence of dozens of African countries in the 1950s and ’60s, movement by land, sea, and air became even more difficult, unreliable, and expensive. In the early years of

Transition, which was based in Kampala, Uganda, there were plans to publish a West African edition with more space for criticism and the potential to reach a wider non-African public. Once

Transition’s editors Rajat Neogy and Christopher Okigbo realized just how expensive such a collaborative venture would be (including exorbitant air freight costs for the distribution), they were forced to drop it.

29 That may help to explain why Okigbo arranged for the simultaneous publication of his own poem “Lament of the Drums” in

Transition and

Black Orpheus in 1965, much like Eliot did for his

Waste Land: it was one way to meet the demand of two audiences at once.

30The rise of the little magazine in Africa is intimately linked with two related changes in the geopolitical and world-economic order in the mid-twentieth century: decolonization and the formation of the global book business.

31 The withdrawal of Western empires from African nations in the 1950s and ’60s coincided with the entrenchment of commercial conglomerates eager to establish their interests in newly independent nations, and the book business was no exception. British publishers (Oxford University Press, Heinemann, Longman), in particular, realized the potential of an untapped Anglophone market and soon began consolidating their interests. This commercial literary exchange between imperial metropoles and their former colonies was also working in the other direction: Anglophone African and West Indian writers were getting published by these same British firms and becoming part of a postcolonial novel boom that is still with us today.

32Amos Tutuola’s

Palm-Wine Drinkard was one of the first modern African novels to reach a wider Western audience. It was composed entirely of Yoruba folktales woven together around the figure of the trickster (in this case one who loves palm wine) and written in what Tutuola described self-consciously as “wrong English.” When Faber and Faber published the novel, it included an image of an original manuscript page in Tutuola’s own hand with a few editorial corrections in order to authenticate their latest discovery.

33 Eileen Julien has called this novel and so many others produced during these decades “extroverted.”

34 It is a term that identifies those novels produced in one place (in this case Nigeria) for consumption in another (in this case England). And there is a very real cost to this extroverted literary production. Extroversion is, very often, dependent on exclusion. Writers like Tutuola, Cyprian Ekwensi, and Chinua Achebe were being published abroad throughout the 1950s, but their books very often could not be afforded or, in some cases, even found in their native countries.

35This is where the little magazine comes in. While so many commercially motivated foreign publishers were “extroverting” African literature, the little magazine, you could say, was “introverting” it by bringing together, issue by issue, modern Anglophone texts for an African readership.

36 Looking specifically at

Black Orpheus and

Transition, Peter Benson has argued that this process was critical to the formation of a postcolonial literature in Africa. And more recently, Peter Kalliney has pointed out that it was enabled, in part, by the promotion of a modernist autonomy once associated in the first half of the twentieth century with political and aesthetic detachment. For some of the African writers who were publishing in these magazines, however, autonomy was redeployed to signify nationalist, anticolonial engagement and a rejection of Cold War ideologies promulgated by the United States and the Soviet Union. Once it was revealed in 1967 that both magazines had received funding from the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF;

Black Orpheus beginning in 1961 and

Transition in 1962), a nonprofit front for the CIA, Neogy and Ulli Beier (founding editor of

Black Orpheus) lost their credibility, even if both were completely unaware of what had been going on behind the scenes.

37 The truth is that institutions like the CCF may have provided funding to these (and other) magazines in Africa and elsewhere, but they did not dictate what appeared in their pages, literary or critical, and made no attempt to control the message in order to maintain the utmost secrecy. Kalliney believes that this “no strings attached” policy of CIA-sponsored organizations coincided with its desire to promote democratic freedom (as opposed to Soviet authoritarianism) and “backed the idea that emerging African cultural institutions were autonomous of colonialism, of the nation-state, even of Cold War ideologies.”

38Black Orpheus and

Transition may have cultivated this sense of autonomy in order to promote an independent literary and critical sphere in countries across Africa, but the network to which they belonged, and the affiliations established therein, made it impossible to detach completely from the geopolitical games going on around them. Even if both editors, then, were ignorant of the funding that was arriving from Western political institutions, they were still involved with them. This oblique relationship, in fact, may not have compromised the content or form of their magazines, but it did force their affiliation with other titles in this foreign-funded network, including

Encounter, the CCF’s Anglo-American magazine, which was being used as part of a more extensive propaganda machine to enlist intellectual, and anti-Communist, sympathizers worldwide. In the decentralized Dada network, which I discussed in

chapter 1, it may have been possible to get off the grid in order to resist political and commercial appropriation (and the very design of the grid in the magazines was an expression of it), but this was not the case for those titles plugging into a Cold War network that was bringing countries and continents into even closer contact with one another. In an interesting twist, modernist autonomy may have been adapted for a political end, but it was not to be confused with avant-garde strategies for autonomy that were always already political, adapted by Dadaists to reaffirm their detachment from bourgeois institutions (political, cultural, and commercial). Decentralization, then, may have worked in the Dada network, which was largely based in Europe, but it should not be confused with a Cold War version that was using globalization, and a black diaspora, as an opportunity to try and consolidate power and increase the range of cultural and political influence.

When

Black Orpheus first started out in Lagos, Nigeria, in 1957, bringing out twenty-two issues until 1967, Nigeria already had a lively and established print culture in place.

39 In addition to the many foreign-controlled newspapers, there were literary magazines, leaflets, periodicals, and scholarly journals printed and distributed by the University of Ibadan. With the exception of the popular general culture magazine

Nigeria Magazine, which regularly included a literary supplement, most of them were amateurish ventures intended for a small audience composed mostly of students and faculty.

40 With a matte cover, woodcut images in bold colors, and thick paper,

Black Orpheus stood out (

figure 5.1). Between the covers, readers would find the contents laid out on the page with generous margins, free from advertisements or letters from readers (and/or the editor).

Black Orpheus was professional in quality, but it would never be confused with a popular magazine. Before long, issues were being picked up by Nigerian universities and used as anthologies for the classroom.

Black Orpheus, unlike so many of its Western precursors, was a little magazine intended for a general readership; it was not predisposed to experimental writing; it was not an enemy of the mainstream commercial literary marketplace, because there was none. There were no wealthy patrons (such as John Quinn or Harriet Shaw Weaver) to support production, so Black Orpheus relied on funding it received from a government-sponsored agency (the Ministry of Education) and, after 1961, from a foreign, Western one (the CIA). The circulation numbers were on the “high” end of the spectrum (around thirty-five hundred at its peak), and that was because it did not have to compete with other commercial or noncommercial publications for contemporary Anglophone literature. Instead of Black Orpheus catering to the fit and few, its readership was still very much in the making, and the editors were more preoccupied with finding an audience than offending one.

5.1 Front cover of Black Orpheus.

Black Orpheus from its inception wanted to do for Anglophone literature what

Présence africaine had done for Francophone literature a decade earlier: provide a space for African writers to publish their work and establish a network of contacts that would put them in dialogue with writers and readers from the West Indies, the United States, and Europe, as well as East, West, and, when possible, South Africa. And the impact of

Présence africaine on the overall scope, scale, and direction of

Black Orpheus cannot be overemphasized.

Présence africaine set the standard for African magazines during this period. It was an ambitious venture devoted to Francophone art, politics, and culture with bases of operations in Dakar and Paris. Not only did it help consolidate the philosophical and aesthetic principles behind the

négritude movement, but it was also an active ideological force behind anticolonial movements worldwide.

Présence africaine was as much a magazine as an institution with connections to the leading Francophone and French writers and intellectuals of the time (included among them Léopold Senghor, Aimé Césaire, André Breton, and Jean-Paul Sartre), and it was part of a subversive tradition of Francophone periodicals published in Paris, Senegal, and New York that were, as Brent Edwards explains, “a threat above all because of the transnational and anti-imperialist linkages and alliances they practiced.”

41

From the beginning, the founding editor of

Black Orpheus, the German expat Ulli Beier, believed that the magazine could mediate between Francophone literature and an Anglophone reading public.

42 In Beier’s one and only editorial statement in the first issue, he laments the fact that “it is still possible for a Nigerian child to leave a secondary school with a thorough knowledge of English literature, but without even having heard of such great black writers as Léopold Sédar Senghor or Aimé Césaire.”

43 Indeed,

Black Orpheus lived up to its promise of making the Francophone world accessible to a wider non-French-speaking audience, and its association with writers and editors from

Présence africaine provided the cultural prestige that it needed to get started. The title itself is a direct translation of “Orphée noir,” the title for an essay written by Sartre and appended in 1948 to the wildly popular

Anthologie de la nouvelle poésie nègre et malgache, which was edited by Senghor.

44 The Francophone and Anglophone writers were part of a shared colonial history, but if the case of

Black Orpheus is any indication, there were often marked ideological differences.

Black Orpheus, though sympathetic to the

négritude movement, eventually distanced itself, focusing more explicitly on literature. Contemporary political and social critiques were avoided, and there was an almost stubborn attempt to keep Anglophone writers free from politics.

The task of reading

Black Orpheus for its form requires taking a panoramic view of its entire print run with an eye toward the structural additions and omissions.

45 As much as the content changed with every issue, the format remained largely the same: a matte cover with a woodcut image, the magazine title in block print on the masthead, printing and publication information with names of the editorial board, table of contents, an assortment of prose, poetry, and fiction in no particular order, followed by a note on the contributors. One of the more curious, though fleeting, formal changes occurs in the fourth issue when a distribution list appears with the addresses of bookstores that carry

Black Orpheus (Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone, Kenya, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Holland, Denmark, and Sweden), a list that gets reprinted an issue later (with England, the United States, France, and Belgium added) and then is never seen again (

figure 5.2)

5.2 “How to Obtain Black Orpheus,” Black Orpheus 4 (1958): 61.

The disappearing distribution list, much like the network maps I discussed in

chapter 1 and the private list of British book dealers in

chapter 2, raises an interesting question about the real and imagined globality of little magazines in general, all of them forced to deal with the question of advertising their range and, in doing so, defining their audience. Being global in such concrete terms does have its benefits: for one thing, it provides clear geographical parameters, making the world of the magazine mappable and showing readers that they are connected to a community of others in Ghana, Germany, and Sweden who are leafing through the same material at the same time. But global concreteness can also work the other way: it can make the magazine seem more provincial precisely by drawing attention to gaps in and between places where it should be going. Where on this list is Uganda, Zimbabwe, or South Africa? How about Barbados, Trinidad, or Jamaica? The pan-African and West Indian trajectories, which became so critical to the success of

Black Orpheus in the Anglophone world, are conspicuously absent. Global distribution, then, may make more of an impact when it remains abstracted, maybe even fictional. Instead of being circumscribed by definite locations, the effect of a global magazine culture can be generated by their absence, by the possibility that a little magazine printed in Nigeria could end up making its way to Sri Lanka or São Paolo.

46Although the distribution list was dropped,

Black Orpheus developed other formal strategies for signifying its affiliation with a more expansive literary and critical scene, including the insertion of a book review section that was in place for the entire run. In the beginning, Beier did a majority of the reviewing himself, often under the nom de plume Sangodare Akanji, but with every issue, new names popped up, many of them of African writers and intellectuals on their way to becoming part of an organic intelligentsia. It would seem logical, of course, to have book reviews in a literary magazine, but in this case, the situation is not so clear-cut. Since so many African novels were being exported and published abroad, the book review was often put there in place of the book itself. The review, for that reason, was not so much concerned with consumption as it was with the less lucrative pursuit of local critical evaluation. This displaced critical practice, one that involved the recognition of books written by African writers and published in England, was part of a symbolic strategy for national and regional reclamation. Africa may have been “losing” so many of its writers to foreign publishers, but magazines like

Black Orpheus were helping to reappropriate, maybe even repatriate, them, making these same books share review space with locally produced plays, poetry, and anthologies, many of them printed by Mbari Publications (thirty of them, mostly poetry, between 1961 and ’65), a publishing house run by Beier for the sole purpose of bringing writers such as Okigbo, Soyinka, Okara, and J. P. Clark to an African audience.

In addition to the “foreign” books by African writers, it was just as common in

Black Orpheus to find reviews of the latest Anglophone little magazines coming out of the West Indies, South Asia, and around Africa. In this case, the affiliation was motivated less by a symbolic reappropriation of African writers than by the desire for solidarity. There is often a paternalistic tone in these reviews, one meant as much to encourage other ventures, some of them already in print for ten years, as to recognize

Black Orpheus’s triumphs. Something else is going on as well. The review of other magazines was a way of establishing a shared postcolonial print culture, one in which the connections between regional literatures only reaffirmed their indigenous, local affiliations. When assessing the importance of

Bim and

Okyeame, one reviewer in

Black Orpheus put it this way: “The function of periodicals in nurturing the new literatures in Africa and the Caribbean cannot be overstated. They represent necessary documentary proof of fashion and growth. Their function is not so much to preserve as to link. Often they stand at the very beginning of the development of local literature, setting up standards and providing a literary market for buyer and seller—the indigenous reading public and the artist.”

47 There is an awareness here in this synopsis that different media can perform different functions in the literary field. In this case, the reviewer contrasts the archival function of the anthology with the serial ephemerality of the little magazine; the relatively rapid production time of the magazine gives it a spontaneity that other print media lack. The monthly or bimonthly turnover of literary production, sometimes at the expense of quantity over quality, has a way of encouraging “links,” as this reviewer put it, between Africa and the Caribbean because it involves a mode of literary production in the present, one that is becoming possible because little magazines are creating the conditions for an international literary standard. Literature produced in Africa and the Caribbean, then, will not only be judged according to a national or regional literary marketplace or tradition. Rather, it will have to stand up in quality against what is coming out in other postcolonial countries with which it shares a common literary-historical trajectory.

Reviews were one place for this international critical standard to be applied, but it was even more forcefully introduced within the longer essays that began to appear under a separate heading in issue 9 (June 1961). “Criticism” is one of the more complicated generic categories in

Black Orpheus.

48 Before it began appearing, there were scholarly journals devoted to traditional, and especially oral, African literature, but there was no available critical tradition in Nigeria for modern Anglophone literature.

49 But the wider availability of a more substantial body of fiction and poetry in five years (engendered largely by

Black Orpheus) made it necessary to establish criteria on which it could be evaluated and judged both as African literature and as world literature. A majority of the critical essays that appeared in

Black Orpheus are devoted to Francophone writers and texts, but they are interwoven with more general surveys of African literature, traditional visual art and poetry (Yoruba, Hausa, and Igbo), and the self-consciously modern Anglophone arrivals (Achebe, Clark, Soyinka, D. O. Fagunwa).

50This separate category for “criticism” reflects a concrete change in the African literary field, one that involved critics from African countries worried about a European takeover and the imposition of foreign standards. The question of who speaks for African writers was hotly debated in the following decades, in newspapers, academic journals, and big magazines alike, but what interests me here is the role that a little magazine like Black Orpheus played in the process. It had European and African critics writing side by side about everything from West Indian novels to Haitian poetry to South African short stories. There was no clearly defined critical practice in place or ready-made concepts to draw from, and though Western comparisons were there to be found, some critics chose to emphasize regional contexts instead.

Elsewhere, in England, Germany, and France, where African works were being published, the question of critical standards was especially vexed. Some African writers wanted to be judged as equals with their Western counterparts; others argued for their cultural, historical, and linguistic singularity. One article about Soyinka’s trip to a drama conference in Edinburgh captures the complexity of the situation. “He was insistent,” the Scottish actress Una MacClean explains, “that drama from Africa deserved to be judged by universal standards of criticism and that the enduring value of any African drama must depend upon the adequacy of its representation of universal human experiences.”

51 For Soyinka and so many others, there was always the danger of being exoticized and treated as something marginal to Europe’s history and literary tradition. “Universal standards,” then, was his way of emphasizing the links that existed between them, a subtle reminder to his foreign audience of a shared history that went well beyond the borders of a single country or continent.

52 The critics writing in

Black Orpheus realized that the field of English literature was opening up to accommodate new human experiences from the former British colonies, and it was an association that would take some getting used to. But leafing through the pages of this little magazine, you discover that criticism was less about anchoring African literature in a European past and tradition than about imagining what such an affiliation might look like in a literary-historical future that included both.

IV

Black Orpheus certainly earned its reputation as “the doyen of African literary magazines.” But even Beier recognized that his magazine had lived long enough to experience middle age. Worried that

Black Orpheus was losing its edge and with a civil war in Nigeria on the horizon, Beier retired from his post in 1968. During an interview that same year, he explained that

Black Orpheus was a propaganda magazine meant to fill a need in what had been a barren literary field. In a decade, the Anglophone literary scene had changed significantly both within Africa and around the world. It was time, he thought, to encourage the local production of low-cost poetry magazines or, if possible, to reinvent his own magazine by changing the title simply to Orpheus.

53 That would be one way to distance the magazine from its original associations with an ideological program first established by

Présence africaine and, in doing so, reach out to an even wider audience, one in which Francophone African writers could be published alongside their English-speaking counterparts.

54 After Beier’s departure, Abiola Irele and J. P. Clark took over the editorship, keeping the original title and bringing out issues sporadically until 1976. The black internationalism that was so carefully orchestrated by Beier and his team of editors gave way to a more parochial focus on Nigeria and Ghana, which was compounded by the collapse of a distribution structure that made

Black Orpheus available only to readers in Lagos.

55

All was not lost, however. On the other side of Africa, in Kampala, Uganda,

Transition was in full swing and had been for four years, and under the editorship of Rajat Neogy, it continued laying the foundations for a network of little magazines that would connect Africa with readers, writers, and critics around the world. “Both authors and editors, as well as the reader,” Neogy wrote in one editorial, “must feel gratified when, to cite one example, a Nigerian writer in the United States has an article published in a magazine in Uganda which is replied to and discussed by correspondents in London, Nairobi, Kampala, Ibadan, Cape Town, and Edinburgh.”

56 In the magazine’s seven-year run (1961-1968) of its first phase with Neogy at the helm,

Transition became a truly international little magazine, with a print run that eventually exceeded twelve thousand (

figure 5.3).

57 Considering that East African literature at the time was lagging far behind Nigeria, that there was very little institutional funding to support it, and that a majority of the audience was hard-pressed for cash, the circulation of

Transition, which equaled the

Dial in its heyday, was no small achievement. When

Transition received ecstatic praise from the

New York Times, the

Observer (London), the

Oslo Dagbladet, the

Globe and Mail (Toronto), and

Die Zeit (Hamburg) for achieving such success on a “shoestring budget,” Paul Theroux was quick to remind everyone that “in a country like

Uganda where 90% of the population is barefoot, even shoestrings are hard to come by.”

58Black Orpheus paved the way for another little magazine in Africa by providing a crew of writers and readers trained in its pages and a design for what the medium might look like. But

Transition was very much a creation of its own, more avant-garde than its predecessor and prepared to rouse, shock, provoke, and alienate whenever possible.

59 It immediately distinguished itself from other publications by claiming, in its inaugural issue, “to provide an intelligent and creative backdrop to the East African scene, to give perspective and dimension to affairs that a weekly or daily press would either sensationalise or ignore.”

60 Topics were not introduced in one issue and then forgotten; they were meant to develop organically over time, and the editor, for that reason, functioned much like an “obstetrician” (Neogy’s phrase).

61 After Obiajunwa Wali’s “The Dead-end of African Literature?” appeared

(Transition 10), in which he argued that African writers should reject the foreign languages imposed on them by colonialism and write in their native tongues, letters poured in for two years. As a courtesy, space was always made for the debate to unfold, and it was assumed that readers would be able to keep track of its attenuated twists and turns along the way.

5.3 Cover of Transition 8 (March 1963).

Transition also found a way to make the reality of a global readership more tangible by introducing a “Letters to the Editor” section, one of the formal features that

Black Orpheus lacked. The letters included in this section ran the gamut from appreciation and bewilderment to disdain and outrage. It was the space in the magazine that allowed readers to communicate not just with the authors of the articles and the editor but with one another. Each letter was preceded by a title and concluded with a name and address where the writer could be contacted directly. As polite as Neogy was with his correspondents (even going so far as to correct silently their grammatical and spelling mistakes when necessary), he was not afraid to pit them against one another or turn their discomfort to the magazine’s advantage. Such was the case after Paul Theroux’s fierce indictment of the white expatriate community in East Africa, which was published with the sardonic title “Tarzan Is an Expatriate”

(Transition 32). Letters of complaint arrived for over a year, and Neogy decided to republish them together with the original article and offer it as a gift to new subscribers.

Though letters to magazines are often treated as a curiosity, one of the guilty pleasures readers can indulge in before getting to the real content, this was not true of

Transition. These letters were critical to the goals of the magazine because they allowed for the kind of open, sustained dialogue that could not have happened anywhere else. Positioned in the opening pages, they acted as an entryway into the discussion and helped to establish continuity from one issue to another. In the first few issues, “Letters” took up a page or two and often included statements of appreciation from countries far and wide. Later on, as the magazine gathered momentum, it was just as common for the letters to run a full four or five pages, some of them long enough to function as stand-alone essays or editorials. Abiola Irele believes that the conversational aspect gave

Transition its force and “helped reduce African problems to some kind of unified intellectual order.”

62 The lead articles in each issue were not treated as the final word; they were printed in order to be “analysed, commented upon, queried—turned inside out, as it were—and sometimes more closely scrutinized” in the letters that followed in subsequent issues, sometimes with half a dozen arguments alive at once.

63 Neogy was very tactical about the kinds of letters he would print, but in his capacity as editor, he actively engineered a space where ideas could be debated; and he did it in such a way that the barriers between professional critics and average readers were lowered. Everyone was free to have an opinion, but only if he or she was ready for debate. In a lengthy editorial on the subject, Neogy put it this way: “Unless writers and readers sense this atmosphere of ‘aggressive non-prejudice’ they will not be tempted to be provocative or even just plain naughty, and the kind of humour that accompanies such exaggerations of sensibilities will be markedly missing. More important, what might creep into the magazine’s columns is a tone of genteelness, sinister and syrupy, where everyone is quietly patting everyone else on the back.”

64By making “Letters” such a prominent formal feature of

Transition, Neogy created an expansive community of readers who could engage in a conversation about current literary and cultural events without any significant time lag. Time was indeed passing between issues, usually two or three months, but the back-and-forth helped make what was being published more urgent.

Transition, then, functioned as a cultural medium in a very literal way, bringing Uganda, East Africa, and the rest of Africa to a wider audience, making domestic issues involving African literature and politics a topic for discussion and demonstrating, finally, that the little magazine can cater to local and global readerships all at once without ever losing sight of its particular time and place. Is it a surprise, then, to find that in the mass of letters from poets, politicians, academics, and students, one arrived from Lionel Trilling in 1965 telling Neogy, “No magazine I can remember reading—except maybe the

Dial of my youth—has ever told me so much about matters I did not know about.”

65 As Trilling himself noticed,

Transition and the

Dial did have a lot in common. Though produced under radically different conditions, they created a space where modern literature could happen. The medium harnessed critical and cultural energies and delivered the message to a public that might otherwise miss out on “matters” worth knowing.

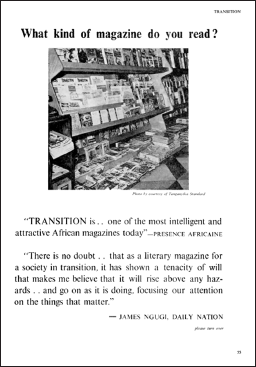

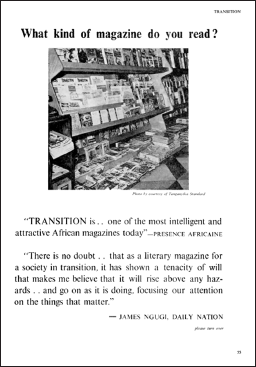

The globality of

Transition was managed in other ways as well. Evidence of its international circulation was scattered throughout the pages, from the different prices on the cover to the advertisements for oil, steel, and foreign car manufacturers to the addresses of the correspondents. One subscription flier that popped up frequently in

Transition contained an image of an unidentified bookstand with magazines arranged neatly on the shelves (

figure 5.4). Because of the angle from which the photograph was taken, only one title can be identified with any certainty. Copies of

Transition are tucked away on a back shelf, in the middle of the rack, and seem larger than the others. And that, of course, is the point. This little magazine stands out in a sea of print, and the simple question at the top, if answered correctly, is there to remind readers they can do the same: “What kind of magazine do you read?” What’s so striking about this image is its generic, placeless quality. This black-and-white bookstand could be anywhere in the world, and that, I think, is why this particular image can do what no distribution list ever could to advertise

Transition’s globality, by asking readers to consider where they are in the world by what they’re reading.

5.4 “What kind of magazine do you read?,” Transition.

In the end, all of these paratextual details suggested one thing: mobility. The world was moving through these pages, and the magazine was moving through the world.

Transition did not exist in an autonomous literary or cultural sphere free from mass consumption, capital, and geopolitical intrigue. It was itself an object of global production and consumption—an example of a postcolonial culture trying to establish itself within a much larger world system during the Cold War. The title of Neogy’s magazine couldn’t have been better chosen. It gestures backward toward Eugene Jolas’s

transition, one of the most successful little magazines published in France in the 1920s and ’30s, while at the same time acknowledging the difference, which is immediately discernible in the capital

T.66 Transition was a magazine meant to register the shocks that were being felt across Africa at a decisive moment in its history: superpowers battling, empires collapsing, nations rising, traditions dying, cultures being born. Unlike

Black Orpheus, it engaged head-on with the social and political issues of the day (love, violence, war, democracy, socialism, drugs, racism) and was unafraid to challenge hypocrisy in all of its forms, especially when it was being advertised as independence or freedom. It was politics that put an end to Neogy’s editorship. His status as the disinterested editor was severely shaken when, as I mentioned earlier, it was discovered that

Transition had been receiving financial support from the Congress for Cultural Freedom (from issue 5 onward).

67 But a second, more fatal, blow came when Milton Obote’s government arrested Neogy for sedition under an Emergency Powers Act.

68 One article by Abu Mayanja in

Transition 32 (April 1968) and a letter to the editor by Steve Lino in

Transition 34, both of them critical of Obote’s proposals for a Ugandan constitution, were cited as evidence of the magazine’s anti-Ugandan stance, and they were both used to justify Neogy’s arrest. After an inconclusive trial in which he was acquitted and then rearrested, Neogy spent four months in solitary confinement before being abruptly released.

69 Transition was revived two and a half years later in Accra, Ghana, one of the few democratic governments in Africa at the time, where the magazine could be published with relative freedom. Its first editorial replied to the events that had transpired back in Uganda and argued that the arrest of Neogy and the closing of its offices was a sign that “a magazine such as

Transition has obviously no useful function in that society.”

70 Transition was not alone. Most little magazines have had to deal with the politics of print in some form or another. The

Little Review had its censors just as

Transition had its political tyrants.

The general lesson, though, has more to do with the form of the magazine.

Transition, as I discussed earlier, prided itself on a democratic mode of communication that encouraged dialogue between everyone involved. This particular form was necessary because there was no other medium in existence that could generate a global readership of this sort at the time. And it was this opening up of Africa to the world that gave the magazine its force, making it a forum for intense political and literary discussion as well as a target for political leaders within Africa who were afraid of opposition.

Transition might not have been welcome any longer in Obote’s Uganda, but as Neogy explained in an open letter to readers, it didn’t matter: “

Transition’s home is also all Africa. And it was at home in the world outside.”

71That’s one way to look at things. It turns out, though, that

Transition really wasn’t at home in “all Africa,” at least when considering that fact that it was unable to get back to Uganda after Neogy’s imprisonment. This raises a question about what it means for any magazine, African, West Indian, or otherwise, to be at home in the world. If nothing more, the examples I’ve discussed here and throughout this book return again and again to the same conclusion: the world is not always home for the little magazine, and that’s especially true if it is meant “to offer honesty,” as Neogy once put it, “when everybody wants slogans.”

72 At least, it is not a home that you can count on being there, which is another way of saying it’s not a home at all but a refuge, a temporary place for the little magazine to spend what there is of an always limited life span. In Europe, the Fascists and Nazis were very often to blame (as I discussed in

chapters 3 and

4); in England and America, the censors and printers had a hand in it (as discussed in

chapter 2); and in Africa, there were dictators like Obote taking over decolonized nations. And maybe that’s why

Transition, like its predecessor

transition, still managed to have such an impact: it was there temporarily to record this radical, though evanescent, change in time, one whose effects continued to reverberate long after copies stopped hitting the shelves.

V

The little magazine, as I’ve been arguing throughout this chapter, is part of a much longer literary history, and its arrival in the West Indies and Africa reveals that changing the address can change the function. And if the inequities of print capitalism with its “large publishing ventures” were responsible for the production of so many little magazines in the West, colonialism, which was followed by decolonization efforts worldwide, did something similar to modern Anglophone literature shortly thereafter. But the argument that the little magazine successfully crossed this great divide separating European high modernism from a soon-to-be-decolonized “postcolonial” literature should not lead us into an all too easy conflation between the two. To do so, we risk erasing their specificity by effectively anchoring one to the other (first the magazine made modernism in the West, then it made modern literature in the colonies/postcolonies, etc.). This sequencing presumes an inheritance, affiliation, and influence that does not always play out as we might expect. With the exception of the Beacon, West Indian and African little magazines began appearing after European high modernism is supposed to have ended, but they were reacting to new historical, social, and political situations that would have been incredibly foreign to the modernist magazine editors, writers, and readers who preceded them.

I mentioned before that the practice of publishing like a modernist was one way for Anglophone writers and critics to begin building an alternative tradition (in the West Indies especially), but it turned out to be more complicated than any of them could have anticipated. The more that West Indian and West and East African literature matured in little magazines, the less this earlier modernist moment mattered as a source of legitimation, and as both examples demonstrated, the little magazine was not simply getting recycled but was getting appropriated to present other non-Western literatures that were building on foreign and indigenous traditions alike. Indeed,

Transition may have reminded Lionel Trilling of the

Dial in its early days, but even he knew that there was a difference between the two; and this difference was not just about what was getting published between the covers. What Trilling sees in 1965 is a little magazine from Uganda arriving in New York long after the

Dial stopped ticking, and it was capable of doing what no

Dial ever could, that is, bring Africa and the West together and, in doing so, make the little magazine less the provenance of modernism’s European legacy and more a promise that a modern Anglophone future was, in fact, still evolving.

To continue thinking through this relationship between modernism, postcolonialism, and the magazine, I want to focus on a single example: Christopher Okigbo’s “Limits” as it first appeared in two installments in

Transition (July and October 1962), before getting reprinted as a single poem in a volume brought out in Nigeria by Mbari Publications (1964).

73 The linguistic and formal difficulty of Okigbo’s poetry has made him both the target of detractors denigrating his deliberate obscurantism, which they identify with an inherited Eurocentrism, and the mantel for supporters celebrating his skillful fusion of Western modernist and indigenous Nigerian/ Igbo literary traditions.

74 More recently, Jahan Ramazani has argued that both positions, in fact, are not irreconcilable. A poet like Okigbo, raised in the context of this colonial hybridity, can be both, a modernist and a postcolonial writer, who uses this inherited Western tradition with its complicated poetic forms as a “tool for liberation.” “To insist in the name of anti-Eurocentrism,” he explains, “that Euromodernism be seen as an imperial antagonist is to condescend to imaginative writers, who have wielded modernism in cultural decolonization.”

75Before looking at “Limits” as an expression of this specifically modernist form of “cultural decolonization,” a few more details regarding its publication history need to be established. Though Okigbo had already published a handful of poems in

Black Orpheus, “Limits” was the first to appear in

Transition and was followed up by “Silences: Lament of the Silent Sisters” (1963), “Distances” (1964), and “Lament of the Drums” (1965). All of Okigbo’s poetry in these magazines is distinguished by the disjointed typographical arrangements on the page, with lines broken up, sometimes creating jarring visual configurations (including pictograms) with entire stanzas and words offset from the middle of the page. The printers for both magazines catered to this desire for experimental layouts, leaving big margins and blank space so that the individual lines and words could breathe. “Limits,” however, is unique in Okigbo’s catalogue because of the way in which it was published. Instead of getting brought out in a single issue, it was divided into two parts, “Limits I-IV: Siren Limits” (composed in 1961) and “Limits V-X: Fragments out of the Deluge” (composed in 1961-1962), each one taking up two full pages (though the second installment includes two rows for each section instead of one). It’s unclear, finally, why this decision to divide was made (and by whom) since “Distances” and “Silences,” which came afterward, were both printed as single installments of four pages, the first ones devoted almost entirely to the title, epigraph, and a brief note of explanation. Whatever the case may be, it turned out that by staggering the publication between July and October 1962, the appearance of the second installment of “Limits” ended up coinciding with the decolonization of Uganda, thereby becoming, quite literally, a poem that straddled both political situations.

This convergence might be nothing more than a beautiful coincidence, but it can still productively frame the way we read “Limits” in

Transition during what turned out to be a momentous transition in Uganda’s history. “Limits,” after all, is a poem that confronts the very question of Western inheritance in Africa’s colonial past (and postcolonial future), and it also stages that confrontation on the page by using the fragmented layouts and interrupted serial installments to dramatic effect. Let me begin, though, with the epigraphs, both of them set in italics (only one in quotation marks), placed in parentheses below the title at the top of the page, and left unattributed, waiting there for readers familiar with the modernist poetic tradition to begin decoding. The first is taken from Ezra Pound’s

Cantos (“&

the mortar is not yet dry”) and the second from T. S. Eliot’s

The Waste Land (“These fragments I have shored against my ruins…”).

76 Next to Joyce’s

Ulysses, these are two of modernism’s most canonical texts, and though Okigbo famously denied the influence of Eliot and Pound on a number of occasions (preferring instead Mallarmé, Debussy, Ravel, Malcolm Cowley, and Tagore), he is uncharacteristically explicit here.

The excerpt taken from Pound’s “Canto VIII” involves Sigismundo Malatesta, fifteenth-century Lord of Rimini, who is passing along a message to his

maestro di pentore, telling him that the walls of the chapel cannot be painted “as the mortar is not yet dry.” In a canto preoccupied with the way that patrons and artists can work together to revive a culture, this line conveys the idea that the moment for such a symbiosis has not arrived. When the mortar is dry, in other words, then the chapel will be painted, and the artist will become an integral part of the culture as it is evolving. The line from Eliot, which appears in the fifth and final stanza of

The Waste Land, works differently. In this instance, the voice is reflecting on some kind of poetic production that has already happened, and it is, as Michael Levenson has persuasively argued, the moment when the “fragments of consciousness” become “a consciousness of fragmentation,” which is there to recommend not unity but transcendence to a higher point of view.

77 By this point in

The Waste Land, the fragments have been “shored up” all right, but they are still left incomplete; and knowing that is infinitely better than being duped into believing that something eternal or total has been produced.

Instead of keeping the epigraph from “Canto VIII” at the top of the page, Okigbo incorporates it several times into the third section of “Limits,” always in italics and always positioned between paragraphs so that it is both in the poem and still strangely set apart. In an appreciation of Okigbo, Beier has argued that his use of a “‘ready-made’ language,” influenced by Eliot and Gerard Manley Hopkins, was one of the ways that he could paradoxically “burst out of the limitations set by the adopted language.”

78 And, indeed, that is what’s happening here in a quite literal way. This “ready-made” epigraph, however, is not just being adopted; it is being stolen (as Eliot would say of all “good poets”), lifted right out of Pound’s poem and made to appear within the context of another sequence of fragments.

79 I want to draw your attention to the fact that Okigbo has also made a subtle modification to the original line, preferring the conjunction “&” over the preposition, or adverb, “as.” “&,” which could signal some kind of causal or temporal connection, instead creates a moment of disruption, one made even more powerful by the fact that the word itself appears in the form of an ampersand:

BANKS of reed

Mountains of broken bottles.

& the morter is not yet dry…80

Silent the footfall

Soft as cat’s paw,

Sandalled in velvet,

in fur

So we must go,

Wearing evemist against the shoulders,

Trailing sun’s dust saw dust of combat,

With brand burning out at hand-end.

& the mortar is not yet dry…

Then we must sing

Tongue-tied without name or audience,

Making harmony among the branches.

In a sequence of jagged line formations, the images and alliterative sounds accumulate one at a time only to pave the way for an action that gets deferred into the future (“so we must go,” “then we must sing”). “&

the mortar is not yet dry,” followed as it is by an open ellipsis, never quite fits in. Sure, it’s there on the page, but instead of getting integrated into the main stanzas of the poem, it remains stuck in between, persistent in its refusal to disappear.

Indeed, this is not simply a moment when we have one poet alluding to another. By keeping the italics, Okigbo reminds the reader that this line first appeared as an epigraph, but it refuses any assimilation either in the lines of the paragraphs or, as could have happened, through the loss of italics. It’s almost as if the epigraph has taken on a life of its own, inserting itself forcefully onto the second page (where there is no epigraph), with the ampersand, separated by blank space above and below, trying to hold them together. Strangely enough, however, these paragraphs resist the connection, and the line itself sticks around like a dog yapping at the heels of a stranger, getting more frantic as this section continues, doubling up in the end, moving over to the left, until the main body of the poem steals the ampersand, removing the italics along the way, before bringing it all to a close:

& the mortar is not yet dry

& the mortar is not yet dry…

& the dream wakes

& the voice fades

In the damp half light,

Like a shadow,

And for what remains of “Limits,” that is the case: this line disappears in the final sections, “not leaving a mark.”

When Eliot’s line appears as the epigraph for the second installment of the poem, the effect is quite different. There is no repetition at all. But the appearance of six sections in double columns has a way of making the entire form of this section of “Limits” resemble a heap of “fragments,” and it becomes, in its own way, the very thing the epigraph names. This particular affiliation, which connects the two poems, can also work in reverse so that “Limits” reflects backward on what Eliot has written, though in this context, the fragments are those coming from the collapse of a foreign empire as it was felt far away from London’s bridges. Throughout “Limits,” Okigbo is careful to establish that his cultural tradition, though partly influenced by a foreign British invader, is also closer to other ancient religions, literatures, and civilizations in Africa and the Far East, so that allusions to Gilgamesh (the character of Enki),

The Golden Bough (the Scottish phrase