Do we ‘snap back’ to the way things were before COVID-19, or do we learn from the dramatic changes that occurred during the pandemic to build a more equitable and sustainable Australia?

Before COVID-19, Australian children and young people fared badly on international wellbeing indicators, ranking 21 out of 41 European Union/OECD countries. A profit-driven culture has weakened the health and welfare systems designed to protect our children and young people. Our youngest citizens have been more negatively affected by the pandemic and are likely to feel its consequences for decades to come.1

We place children’s and young people’s development at the centre of society. How do their communities and environments affect their wellbeing? How have the dramatic changes during COVID-19 affected them? And how can we optimise a civil society that could wrap around and nurture our youngest citizens after COVID-19?

Civil society and uncivil society

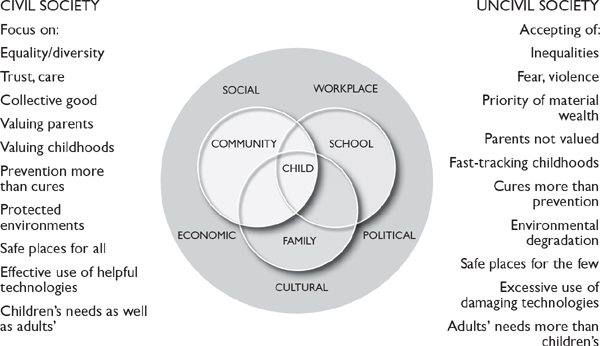

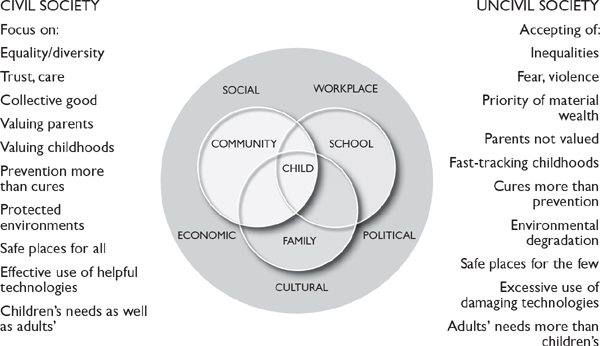

A child in the family is surrounded by a close circle—school, community—within a wider circle of environmental influences: workplaces, social, economic, political and cultural (see Figure 1). These influences cannot be controlled by those close to the child, yet they can either enable or disable healthy child development. If these environments are dominated by influences on the left, then a civil society exists that benefits not only children but all age groups. If, however, these environments are dominated by influences on the right, this has a devastating effect on the health and wellbeing of all. Before COVID-19, Australia was more dominated by factors on the right.2

Figure 1: Societal factors that promote a civil society for young people

Before COVID-19

Before COVID-19, our economy was internationally lauded as having had a ‘remarkable run’. Our universal healthcare system was judged one of the best in the world, providing essential services to all Australians. We had some of the lowest rates of smoking internationally, and the rates of serious alcohol drinking in teenagers were falling. While introduced too late, universal paid parental leave was a huge gain, both to enhance parenting and to make a statement about valuing children and those who care for them. Our system of family benefits was better than that of the United States.

However, despite these strengths, wealth inequality had disproportionally increased, eroding the quintessential Australian ‘fair go’. One in six Australian children lived in poverty (OECD definition), with the sharpest rise occurring during the so-called ‘economic boom’ from 2003 to 2007. Trust in our political and public institutions was falling, with almost three-quarters of Australians suspicious ‘that people in government only look after themselves’ and over half viewing government as ‘run for the big interests’.3

Inequalities are particularly toxic for children and young people. One in three children from disadvantaged backgrounds will start school behind on at least one developmental milestone. Children from low socioeconomic backgrounds are also more likely to be obese, experience tooth decay and suffer from mental health problems. These problems track through adolescence into adulthood, setting up a lifetime of disadvantage.4

After World War II, a social-democratic consensus prevailed that built publicly funded health and welfare services in many countries. But this was undone in the late 1980s with the wave of privatisation that characterised the neoliberal age. Wealth creation and individual greed took over, with excessive focus on consumption, profits and shareholders’ rents.

The neoliberal agenda successfully constructed a narrative portraying the public sector as weak and a drain on society. This infiltrated our social architecture, damaging our society and services such as health, child care, disability and vocational education as they were increasingly outsourced to for-profit organisations.5

The fee-for-service model of medical care focuses on disease care rather than prevention. Moreover, it tends to increase the costs of care, much of which may not be necessary, and some not actually safe.6 For instance, pathology services nationally are dominated by a small number of large corporates whose main aim is to make profits rather than serve their populations.7 Fee for service drives an oversupply of specialists in cities and a significant lack of access to necessary services outside the metropolitan area.

Medicare needs to be overhauled, with consideration given to abolishing fee for service and remunerating doctors well for the work they do. It currently works neither in the interests of patients nor of many doctors: during the pandemic, many GPs have had their income cut as people avoided doctor visits.8

This funding model has led to vast inequalities in access to health and welfare services, the most obvious being for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. But this is also the case for rural populations and those from low socioeconomic backgrounds. For instance, compared to those from the least disadvantaged backgrounds, the most disadvantaged were 2.5 times more likely to state a barrier seeing a dental professional or filling a prescription.9

We were also in the grip of a mental health crisis, where our ‘dysfunctional public mental health system [saw] patients cycle in and out of emergency rooms’.10 Our private paediatric mental health system was also failing, with lengthy wait times for appointments, large out-of-pocket costs and a lack of services in rural areas. Mental health services were out of reach for those most in need.

As a result, despite our so-called world-class universal healthcare system, our most vulnerable were falling through the cracks. Perhaps not surprisingly, for the first time in history, our children are likely to have shorter lives than their parents.

Socially, we were also fractured and becoming a more individualistic society. One in four Australians reported feeling lonely for at least half of every week, and only one-third reported that they trusted their neighbours—most likely because they don’t know them well enough. On average, we spent four-and-a-half hours commuting to work each week, substantially reducing family time. Our workplaces were becoming a two-class society, marked by those with stable, well-paid employment with benefits (sick leave, parental leave), and those in the rising ‘gig economy’ employment without such benefits. Young people were more likely to be in the latter category.

Politically, corporate lobbyists, aided by the shock jocks and News Corp, had become all-powerful and much more successful at influencing government decisions than evidence, data and science. It seemed that many politicians and corporate leaders regarded science as an annoyance that they could ignore or even denigrate.

It was clear that economic growth and vested interests came before our children’s health and wellbeing. For example, in the midst of our obesity crisis (one in four children and one in three adults being overweight/obese), junk-food advertising to children thrived and our leaders refused to consider a sugar tax. Despite two decades of obesity research illustrating the role of diet in the obesity pandemic, and the fact that it was estimated to cost Australia $11.8 billion each year,11 our leaders ignored the science.

In the case of climate action, the people were protesting—especially our children, who were watching their future natural world being sacrificed for the short-term financial gains of a select few. The world’s leading climate scientists made dire predictions about what lay ahead if we continued down our path of destruction, particularly for our children and young people. Yet our leaders continued to ignore the science, subsidising the fossil fuel industry annually to the tune of an estimated $29 billion or, on a per capita basis, $1198 per person.12

Economic growth was the mantra guiding decisions before COVID-19 and came at the cost of our children and young people’s environments and communities. This hardly paints a picture of a society that we would want to ‘snap back’ to.

During COVID-19

In a dramatic shift, the pandemic saw our leaders prioritise our health over the economy. Governments not only listened to our scientists but acted on evidence, used data and valued science. The rapid embrace of science reversed almost twenty years of ignoring calls to avoid the health effects of climate change, tackle obesity, prevent mental health problems and reduce the Indigenous ‘gap’. Scientists were no longer denigrated but praised. Our health professionals, teachers and childcare workers were valued for their essential services. And Australians’ trust in our government and public services rose dramatically.13

Profits and lobbies and partisan politics were cast aside, and human lives and societal wellbeing were paramount. This led to the most fundamental changes in our social architecture that we have witnessed in recent times, including free child care, a fair basic income for those looking for work, and financial assistance to retain employees during the height of the pandemic. This social democratic agenda was implemented almost overnight.

We also witnessed the strength of our civic values and society, as people put the health and wellbeing of others above all else by ‘staying home to save lives’. There was more time together and the pace of life slowed. We retreated to our neighbourhoods (albeit at a distance) and, for some, this likely forged new connections and relationships. Commute time became a thing of the past and breakfast with the family a daily ritual. And in an outcome that may help working mothers, dads at home realised how big (and enjoyable) the task of child-rearing is.

Yet the pandemic also exposed the vast inequities of our society and the weaknesses of our systems. Many in ‘gig economy’ employment had no benefits, and many, particularly young people, lost incomes almost overnight. Similarly, online homeschooling and telehealth marginalised our most vulnerable children and young people, where online learning and consultation were out of reach.

The pandemic also demonstrated the problems with mass privatisation. The pathology industry allegedly threatened the federal government that they would stop COVID-19 testing unless the subsidy increased from $24.40 to $100, claiming that they were only making a ‘small profit’. But with mass testing and millions of tests already completed, this hardly points to small profit. It shows how the government can be bullied by the private sector when health care becomes a commodity rather than a fundamental human right.

As ‘lockdown’ restrictions ease, there are also worrying signs that the economy will be prioritised ahead of our health and wellbeing, and that the profits of a select few will determine our recovery path.

The pandemic exposed the dire consequences of our rising inequities, and the weaknesses of our increasingly privatised health and welfare systems. With this reflection, it is clear that although we might think we have lost much during the pandemic, we can also consider what we might have to gain after COVID-19.

After COVID-19: What should we do next?

1. Urgently address the growing inequalities in wealth by improving our unfair and unnecessarily complex taxation system and ensuring our welfare systems keep people out of poverty.

2. Transfer our health and welfare systems back to the public system to improve healthcare access and quality and create new jobs: economist Richard Denniss has pointed out that ‘capital intensive mining and construction projects … create far fewer jobs per billion dollars spent than spending on health and community services’.14

3. Fund universal free child care to reduce inequities in school readiness and ensure all parents who want to work have the opportunity. This could also help reduce the gender wage gap, enhance women’s superannuation and add to tax revenues.

4. Value all workers and ensure they have fair conditions, to end the ‘gig economy’ and help reduce inequities—for example, by ensuring all parents have paid carers’ leave to attend to sick children, and holidays to enjoy family time.

5. Commit to zero emissions by 2050. The existential threat of climate change is the biggest threat to the survival of our natural world and future generations, and to the health and wellbeing of all, particularly our children and young people.

6. Ensure our citizens’ voices are heard.

• Implement the Uluru Statement from the Heart. This will enshrine the First Nations Voice in the Constitution. Such an act could improve the value and quality of First Nations’ services immediately.

• Implement citizen engagement strategies to ensure that citizens’ voices are heard, rather than the voices of vested interests and lobbyists. The ‘Wales We Want’ initiative is a prime example of how successful such strategies can be.15

7. Make decisions based on evidence, and value science. This will improve outcomes and transparency, thereby helping to improve trust in governments and our institutions.

8. Measure societal progress via a wellbeing framework (for example, a wellbeing budget). Many countries are trying various models of engaging their citizens to guide their national budgets based on wellbeing rather than on GDP as a singular measure.16 These models put human, social, natural and economic capital at the heart of budgeting.

This wish list needs an intergenerational lens to see the benefits—one where we put civil society ahead of profits. Yet if we could deliver on these wishes, there is no doubt that both children and society would thrive. Turning the juggernaut around is a major challenge, but as Rebecca Solnit says, ‘Shared calamity makes many people more urgently alive, less attached to the small things of life and more committed to the big ones, often including civil society and the common good.’17