Conchas ala Parmesan

Parmesan Scallops with Spinach & Peruvian Béchamel

I felt so grown-up the first time at my uncle Ruben’s house when I learned how to make conchas a la parmesana when I was ten or eleven years old. For such a common, everyday dish (in Peru, at least), it’s such an elegante presentation. The scallop shell doubles as a baking and serving dish. Years later, when I actually was grown up and working in a fancy hotel restaurant in London with equally elegant clientele, we had a few customers in from Milan in one night. They swore by the traditional Italian view that seafood and cheese should never be paired together. We got into a lively conversation (I pointed out that we have generations of Italians in Peru; we even use the word ciao to say good-bye instead of the Spanish word adios), and they eventually agreed to let me try to convince them otherwise. Instead of the more traditional mix of butter, ají amarillo, lime juice, and Parmesan, I made the scallops with my creamy Parmesan-béchamel sauce (see sidebar, page 55) as the base. They loved it and gave me big hugs and loud Italian kisses. I probably should have also thanked them. Parmesan arrived in Peru with Italian immigrants.

In Peru, the dish goes by the name conchitas a la parmesana because the scallops used are often smaller than those you find in the United States. I use massive scallops (what are called jumbo scallops in the States), so I couldn’t call this dish “little” anything. If you manage to get your hands on scallops with the orange roe still attached, even better. It’s the caviar of scallops.

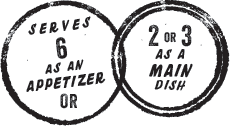

If you have all of the components ready, this is a very quick dinner party dish, but it is really important to not overcook the scallops or they will become tough. Cook them until just medium-rare, so they almost melt when you cut into them. With the butter sauce and béchamel, this is a very rich dish, so plan on one per person as an appetizer. For a casual supper, bake two conchas per person, three if you are really hungry, and bake several together in larger au gratin dishes. If your fishmonger doesn’t have scallop shells, look online for “scallop baking shells” from European importers, or use ramekins.

- 2½ tablespoons frozen unsweetened yuzu juice, thawed, or fresh lime juice

- 1 teaspoon ají amarillo paste, store-bought or homemade (page 34)

- ¾ teaspoon kosher salt

- 2 bunches baby or 1 bunch mature spinach, or 1 (10- to 12-ounce) bag baby spinach

- 6 jumbo sea scallops (about 2 ounces each), or more if smaller (about 12 ounces total), with their shells, if available

- 6 tablespoons ají amarillo butter (page 38), at room temperature

- Peruvian Béchamel (page 55)

- ½ cup grated Parmesan (about 2 ounces)

1 Preheat the oven to 400°F and position a rack in the bottom third.

2 In a small dish, whisk together the yuzu juice, ají amarillo paste, and salt and set aside.

3 Fill a medium saucepan halfway with water and bring to a boil. If using bunched fresh spinach, remove any tough stems and wash the leaves well. If using prewashed bagged baby spinach, you don’t need to stem the spinach. Add the spinach to the boiling water and stir briefly, then drain immediately. Rinse the spinach under cold water for about 15 seconds to cool it and firmly squeeze out any excess water. Spread out the leaves on a few paper towels to dry.

4 Rinse the scallops and their shells under cold running water to remove any grit and gently pat both dry with paper towels. Spread 1 tablespoon of the ají amarillo butter on the bottom of each scallop shell, or in six 8-ounce ramekins or small au gratin dishes. Divide the spinach among each shell or ramekin (a good 2 tablespoons in each), and nestle one scallop on top of each. (If you are serving the scallops as a main course, divide the butter, spinach, and scallops evenly among two or three wider au gratin dishes.)

5 Place the shells or dishes on a rimmed baking sheet and bake until the scallops just begin to turn white along the edges but are still translucent in the center, as few as 5 minutes if they are on the smaller end of “jumbo,” or up to 8 minutes if larger. Remove from the oven and preheat the broiler to high.

6 Dived the béchamel among the scallops (1½ to 2 tablespoons each) and scatter the Parmesan on top. Broil the scallops until the cheese turns golden brown, 1 to 1½ minutes, depending on how close the scallops are to the broiler’s flame (check the scallops regularly). After 2 minutes, even if the scallops still don’t have much color, remove them from the broiler so they don’t overcook. You can use a kitchen torch and quickly blast the béchamel and cheese in spots like you are making a crème brûlée crust, or serve the scallops as they are; they will still be good. Drizzle about 1 teaspoon of the yuzu–ají amarillo sauce on top of each scallop. Carefully transfer the hot scallop shells or dishes to serving plates and serve inmediatamente.

Peruvian Béchamel

Makes about ¾ cup

At home, I sometimes double or triple this béchamel sauce recipe so I have leftovers to make creamed spinach, or to spoon some on top of sautéed broccoli, cauliflower, or boiled potatoes for my kids. In honor of my Italian friends back in London, I may have to invent a seafood lasagna with plenty of Parmesan.

The sauce seasons both the spinach and scallops, so it should be on the saltier side. Adding a splash of lime juice after cooking really brightens all of the flavors. If the sauce separates as it cools, rewarm it over medium heat for a minute or two and stir until everything is reincorporated.

- 1 tablespoon olive oil

- 1 tablespoon unsalted butter

- ¼ cup roughly chopped shallots or red onions

- ¼ teaspoon ají amarillo paste (page 34)

- ½ teaspoon pureed garlic (page 37)

- 1 small bay leaf

- ¾ cup heavy cream

- ¼ cup grated Parmesan (about 1 ounce)

- 1 tablespoon all-purpose flour

- 1 teaspoon fresh lime juice

- ½ teaspoon kosher salt, or to taste

1 Heat a medium sauté pan over medium heat—not too hot. Add the olive oil and the butter. When the butter has melted, sprinkle the shallots into the pan and sauté them for 2 to 3 minutes, until translucent. With a wooden spoon, stir in the ají amarillo paste, followed by the pureed garlic and the bay leaf. Reduce the heat to medium-low and cook the sauce, stirring regularly, for 4 to 5 minutes, until the butter turns golden brown. If the butter begins to blacken, remove the pan from the heat for a minute or two, reduce the heat, then return the pan to the heat to continue cooking.

2 Stir in the cream, raise the heat to medium, and bring the cream to a low simmer. Stir in the Parmesan and the flour (don’t worry if the flour clumps a little) and stir the sauce continuously for a good 2 minutes to cook out the raw flavor of the flour. The sauce should be pretty thick.

3 Remove the bay leaf and transfer the sauce to a blender. Add the lime juice and salt and puree until very smooth. Taste, and add a little more salt if needed. Use immediately, or let cool to room temperature and refrigerate in a covered container for up to 3 days. To serve, gently rewarm the sauce over low heat.

“Peruvian-Style” Béchamel

Chefs often have recipes that start as one thing and evolve into something else seemingly entirely on their own. This béchamel sauce is one of those recipes. While working on this book, my cowriter, Jenn, asked what made me combine several different cooking techniques to make my favorite béchamel; I hadn’t even realized that’s what I had done. For me, this was just what made sense to make a really flavorful béchamel.

In Peru, classic creamy sauces like huancaína sauce (page 168) are usually pretty simple, made by pureeing together all of the ingredients. Cooked sauces tend to start with an aderezo, ingredients that are slowly sautéed to give a sturdy flavor backbone to any dish. The idea is similar to a French mirepoix, only instead of white onions, carrots, and celery, an aderezo is often made from red onions, ají amarillo or panca paste, and garlic, but it varies. Sometimes hot sauces are pureed afterward in a blender to give them a creamy consistency, but not always.

On the opposite side of the creamy sauce world, there is a classic French béchamel. You cook up a roux of butter and flour, whisk in milk or cream, and simmer the sauce until it is thick and creamy. You can’t add too many ingredients on the front end, or the sauce will get lumpy, which means the flavor tends to be rich with butter but not as complex.

Bringing the two together, to make my béchamel sauce, first, I make a really flavorful aderezo and sauté the ingredients slowly in butter to get that nice golden brown flavor. Next, I stir in the cream, bring it to a simmer, and add a little Parmesan and the flour (usually, to make a béchamel you add the flour to the butter before the cream). When you make the sauce this “backward” way, you get an incredible depth of flavor from the aderezo ingredients that you don’t get with a classic roux. Since everything is pureed in the blender after the sauce thickens, as you would with a cold Peruvian cream sauce, it doesn’t matter if you get a few lumps from adding the flour toward the end of cooking. And like any good Peruvian, I can’t help but add a squeeze of lime juice at the end to brighten up the flavors. (Adding acid to a cream sauce is usually a surefire way to end up with a curdled sauce, but since you puree everything, it doesn’t matter.) The result is a thick cream sauce with a more intense flavor.