Shan State, in eastern Burma, encompasses a beautiful plateau of rolling highlands, lakes and forests that extend all the way from the central plains to the borders of China, Laos and Thailand. This vast hill tract, which accounts for around a quarter of the country’s total surface area, has always been something of a land apart – geographically remote, difficult to govern and perennially vulnerable to invasion. For most of the past four decades armed conflicts of one kind or another have rendered much of it off limits to foreign tourists. Ceasefires signed by the Burmese government with more than a dozen insurgent groups have significantly improved the situation, although low-level fighting between the government and the Shan State Army continues to rumble on in a few remote areas. The main tourist destinations, however, are now at peace, with a corresponding rise in visitor numbers – not just in the popular destination of Inle Lake, in the west of Shan, but also the much less explored frontier districts of the state’s far east – heartland of the so-called “Golden Triangle”.

History

The present-day population of Shan State is mostly descended from Mongol soldiers who accompanied Kublai Khan in the late 13th century and never left. Since then, the region has been dominated by a mosaic of petty princedoms ruled by saopha or sawbwa, chiefs who were allowed to retain their regalia and privileges after the Konbaung Dynasty annexed the area in the 18th century. In return, the chiefs paid tribute to Mandalay and provided troops for the Burmese army. Shan soldiers were at the forefront of the Konbaung’s wars of conquest in the south of Burma and played a seminal role in the First Anglo-Burmese War of 1824–26.

In order to ensure the good behaviour of the Shan Chiefs, the Burmese kings kept their sons as de facto hostages at court. The British did something similar after they took the region in the late 1880s, only instead of holding the Shan boys in the capital, they sent them to public schools in the hill town of Taunggyi, and later to universities in Britain. The result was a generation of anglophile local rulers who were more sympathetic to British rule than that of their former Burmese overlords. When the latter came to dominate the nation’s political life following independence, many of the Shan chiefs began agitating for self-rule, leading to the formation of an embryonic insurgent army on the Thai border.

The political situation became even more unstable in 1950, after 20,000 troops of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army swarmed across the frontier to oust Kuomintang (KMT) forces that had settled in the area. While the Chinese communists fought from the east, the Burmese battled from the west. In the end, the KMT were defeated and the People’s Liberation Army headed home triumphant, but large numbers of Chinese troops chose to stay behind in Shan – the first of several waves of immigration from neighbouring China that has totally changed the ethnic complexion of the state’s eastern flank.

A full-blown Shan insurgency erupted in 1964 after General Ne Win’s military coup. Fuelled by income from the Golden Triangle’s booming opium trade and illegally mined rubies, this rumbled on for nearly four decades until the government and various strands of the Shan State Army (SSA) signed a ceasefire agreement in 2011–2012 (although fighting continues in places).

Armed rebellion has also dogged neighbouring Kayah State, homeland of the Karen people, which has seen some of the worst atrocities committed by the Burmese government and their insurgent adversaries in the modern era. Although the situation in Kayah looks more peaceful now than it has for many years following a ceasefire agreement of 2012, the region can still only be visited on government-sanctioned tours.

What to see

The strife of the recent civil wars feels a world away from serene Inle Lake, the region’s main attraction, whose glassy waters are cradled by verdant hills on the placid, western rim of the Shan plateau. While you’re in the area it’s well worth making a detour up to the former British hill station of Kalaw, a genteel Raj-era town whose colonial architecture and mild climate make it an ideal springboard for treks into the neighbouring hills, home to a colourful array of ethnic minority groups.

Young residents of the stilt houses of Nampam village.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

East of Shan’s administrative capital and main market town, Taunggyi, the landscape grows more rugged as you approach the so-called “Golden Triangle”, where the Burmese border meets those of Thailand, Laos and China. Fought over for much of the 20th century by rival states and drug lords, this backwater region is nowadays stable and accessible again. A strong Thai influence pervades the streets of its attractively old-fashioned capital, Kengtung, home to assorted Buddhist monasteries and temples, while the hilly hinterland is populated by minority groups whose way of life has changed little since the Konbaung Dynasty ruled more than a century ago. Overland travel to Kengtung is, however, currently forbidden, and the town can be only be reached by air (from Mandalay, Yangon or Heho near Inle Lake).

Inle Lake

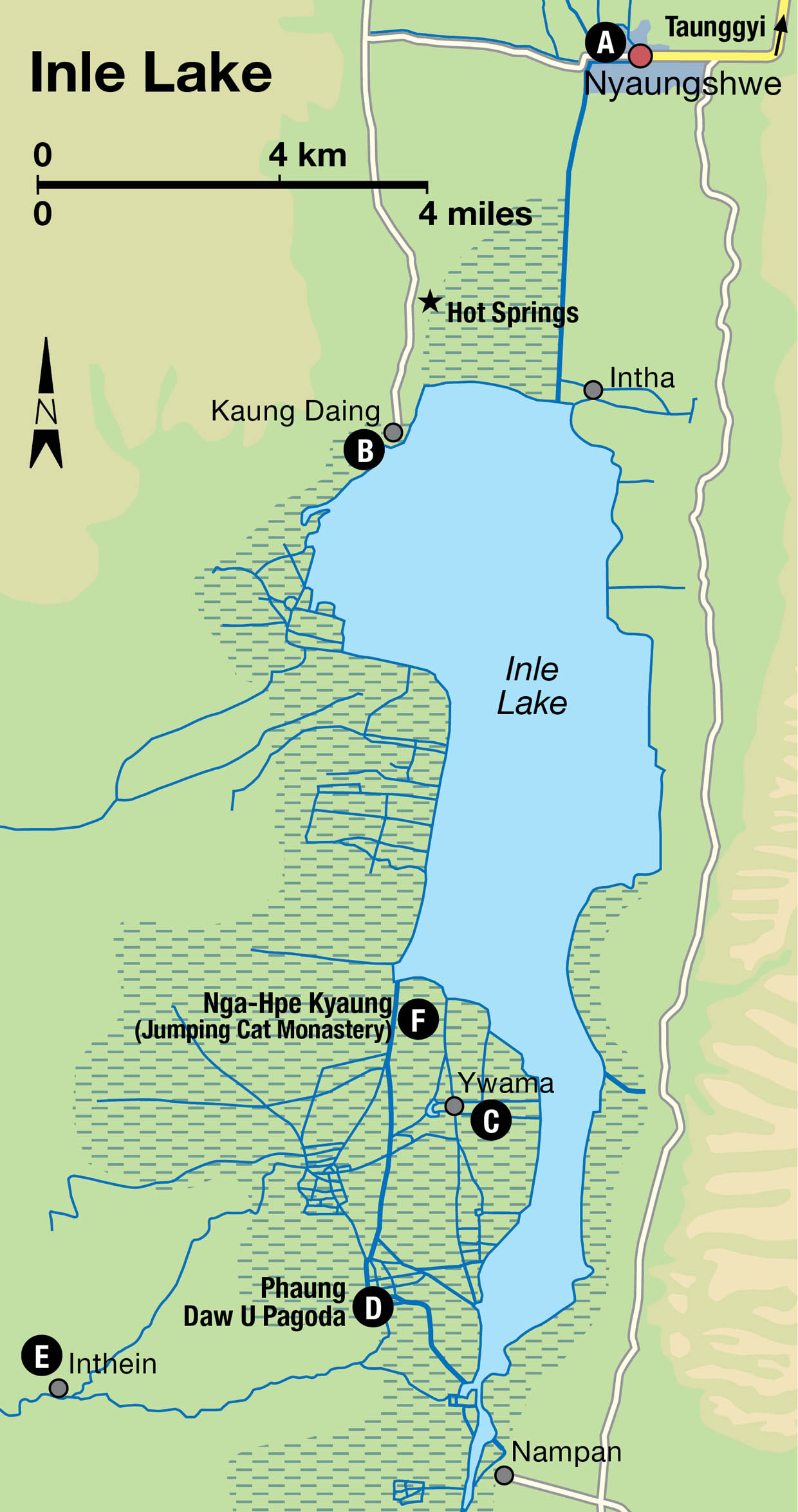

Thanks to its cooler climate and picturesque setting in the lap of the Shan Hills, Inle Lake 1 [map] these days attracts serious numbers of visitors during the winter tourist season. In between leisurely sojourns gazing from their hotel verandahs across the water, travellers while away days taking boat trips to ruined stupas, hot springs and the stilted villages of the local Intha people. The Intha are responsible for Inle’s defining image – that of the local “leg-rowing” fishermen, who propel themselves across the lake’s surface by wrapping one leg around oars fixed to the stern of their flat-bottomed canoes.

One legged rowing technique and floating gardens, Inle lake.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Around 70,000 Intha live in the various towns and villages scattered around the shores of the lake, which measures approximately 21km (13 miles) from top to bottom, and 11km (7 miles) across. .An immigrant tribe from Dawei in Myanmar’s far south, the Intha left their former homeland in the 18th century to escape the perpetual conflicts between the Burmese and Thais. As well as their distinctive rowing technique, they are also skilled metalworkers, carpenters and fishermen – local men setting long conical traps, which are used to catch Inle’s metre-long carp, giant catfish and eels, are a common sight.

You will probably also see the Intha’s “floating gardens”, or kyunpaw, created by collecting weeds from the surface and lashing them together to form metre-thick strips. These are then anchored to the bed of the lake with bamboo poles, and heaped with mud scooped from the bottom. One advantage of the method is that it can be used regardless of fluctuating water levels. Crops – including cauliflower, tomatoes, cucumbers, cabbage, peas, beans and aubergine – are grown year-round.

Surplus produce is taken by boat to the local markets, which are held each day in different villages around the lake (rotating between villages on a five-day cycle). These also provide a popular day-trip destination for visitors, attracting minority people dressed in their finest traditional garb, and are a great source of authentic souvenirs, such as locally handwoven Shan shoulder bags and longyis made from lotus silk.

Canoeing around Nampam village on Inle Lake.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

With regular connections to Heho airport (40km/25 miles northwest) from Yangon, Mandalay and Bagan, getting to Inle is straightforward if you fly. Overland it’s a tougher undertaking by bus or taxi along mountain roads via the junction town of Shwenyaung, or the highland capital Taunggyi to the lake’s principal town and transport hub, Nyaungshwe.

Sampling the goods in Kalaw market.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Nyaungshwe

Nyaungshwe A [map], the oldest of about 200 Intha settlements around Inle Lake, stands on a 5km (3-mile) -wide belt of silt and tangled water hyacinth on the north side of Inle Lake. Since the recent revival of tourism, the town has grown considerably and now holds the lion’s share of the area’s accommodation, restaurants and other visitor facilities. Lake trips by motorised boat, canoe or bicycle are the main focus here, but you could spend an enjoyable morning looking around the Yadana Man Taung Pagoda, the town’s principal Buddhist shrine, whose centrepiece is a towering, gilded stupa made to a unique seven-stepped design.

The largest monastery in Nyaungshwe is the Kan Gyi Kyaung, a couple of blocks east of the Yadana Man Taung on Myawady Road, which boasts a resident population of around 250 monks. Photographers, however, tend to make a beeline for the Shwe Yaunghwe Kyaung, a couple of kilometres north of the centre, whose teak-built ordination hall is lined with picturesque oval windows – the young novices know the drill and pose cheerfully in them for visitors as soon as any turn up.

For something a bit different, the Red Mountain Winery (www.redmountain-estate.com; daily 9am–6pm; free), a short drive (or longer bike ride) southeast of Nyaungshwe off the road to Maing Thauk, is worth a visit. The main engine behind Myanmar’s fledgling viticulture industry, Red Mountain’s French winemaker and team turn out some surprisingly good vintages, including reds, whites, plus a rosé and port. Sampling one of the winery’s inexpensive four-glass taster sets on the terrace of their beautiful outdoor pavilion is a nice way to pass an hour.

Kaung Daing

Kaung Daing B [map], to the southwest of Nyaungshwe on the lakeshore, is the site of a couple of large upscale resort hotels. The village also has some enjoyable hot sulphur springs (daily 8am–6pm; charge) and is a popular destination for day-tripping tourists wishing to see the local Padaung tribeswomen, with their fantastically elongated necks clad in brass coils. The small community, who live on a reserve near the village, are originally from Loikaw in Kayah State.

Ywama

About 12km (7.5 miles) from Kaung Daing on the southwest side of Inle, the village of Ywama C [map] is about as touristy as the lake gets, with a clutch of hotels, restaurants and lanes lined with souvenir stalls, as well as a fleet of water-borne trinket sellers hassling any visitors who venture out on boats. Every tour group in the region comes here once every five days for the village’s famous “floating market”, which started out as a purely authentic local bazaar but has been overwhelmed in recent seasons.

Ywama serves as a springboard for boat trips to the nearby Phaung Daw U Pagoda D [map], venue of one of the country’s most important festivals. The event centres around the procession of four sacred images which are enshrined with a fifth in the temple. These were carried back to Burma by the widely travelled 12th-century King Alaungsithu upon his return from the Malay Peninsula, and then deposited in a cave near the lake. They were not rediscovered until centuries later, since when they’ve been covered with so many layers of gold leaf that they’re unrecognizable as Buddha figures.

A barge carrying the Buddha images of Phaung Daw U Pagoda during the festival of the same name.

Photoshot

The Phaung Daw U festival

The Phaung Daw U Pagoda’s annual festival, celebrated during the Buddhist month of Thadingyut (September/October) to mark the beginning of Buddhist Lent, is Shan State’s principal religious celebration, attracting devotees from across the region and beyond. Its focal point is the parade of the temple’s amorphous Buddha statues around Inle’s 18 largest settlements aboard a re-created royal barge with a huge gilded karaweik bird at its prow. Celebrations, which lasts around 20 days, are a reminder of the pomp that once attended the Buddhist courts.

Only four of the five sacred images are used in the parade. Legend has it that all five were at first employed in the procession, but that in 1965, a storm capsized the barge carrying the images, and it sank to the bottom of the lake. Only four images were recovered and these were taken back to the Phaung Daw U Pagoda, where, lo and behold, the fifth one was also found, still covered with weeds. Since then, this fifth image has never left the pagoda. Today, the spot on the lake where the barge capsized is marked by a pole crowned by the sacred mythological hintha bird. The Phaung Daw U festival draws crowds from all over Myanmar, arriving in boatloads carrying elaborate offerings. They come not only for the “royal” procession, but also for the famed leg-rowing competitions, where crews of Inle oarsmen race each other in sprints around the lake.

Inthein

Among the most popular day-trip destinations on Inle Lake is the village of Inthein E [map], which sits at the end of two long, winding rivulets running inland just southwest of Ywama and the Phaung Daw U Pagoda. Lined by reed beds and open fields, the channels narrow as they approach the village, which is famous for its collection of crumbling Shan stupas. The most accessible of these is Nyaung Ohak, a short stroll south across a footbridge from the village proper. While some have been restored with fresh coats of limewash and gold leaf, many more are half-collapsed and overgrown with weeds. Stucco reliefs of guardian deities and mythical creatures flank the ornately carved fronts of the older monuments. From Nyaung Ohak, you can follow a long covered walkway lined with souvenir stalls uphill to the Shwe Inthein Pagoda, a much larger complex of 17th-century stupas arranged around a central shrine. The views over the lake from here are magnificent.

Tip

Find out the name of the village where the Phaung Daw U festival will take place on the day that you wish to see it and hire a boat the night before. Be sure to start out early (preferably before 5am) as festivities kick off before dawn.

The largest numbers of visitors descend on Inthein when it hosts one of the lake’s famous five-day markets, which fills a dusty market square in the centre of the village. To escape the melee, follow the lane running from the northwest corner of the square and take the footpath striking left off it shortly after to the stupa crowning the hilltop above, from whose base extends another stupendous panorama over Inle and its mountain backdrop.

Crumbling stupas at Inthein Paya.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Nga Hpe Kyaung (Jumping Cat Monastery)

Formerly one of Myanmar’s wackier visitor attractions, Inle’s Nga Hpe Kyaung F [map], better known as the “Jumping Cat Monastery”, thanks to the resident felines who were until recently trained to leap through hoops in exchange for titbits. The cats are still in situ, although the resident monks have now abandoned the practice of urging them into displays of feline acrobatics, fearing it was exhausting the animals, who now simply lounge around, doing what cats generally do. The monastery remains worth a visit, even so, thanks to its fine old teak architecture, the superb collection of antique Buddhas in its meditation hall and the sweeping views outside – while the presence of the occasional (albeit non-jumping) cat adds its own particular charm.

Performance of a show held in Heho which features jumping cats.

iStock

Taunggyi

The administrative centre and main market hub for the Inle Lake region is Taunggyi 2 [map], seat of the Shan Council of Chiefs during the British colonial period. The town was founded by Sir James George Scott, one of the most respected colonial officers in the history of British Burma. A devoted student of Burmese history and culture, Scott, under the pseudonym Shway Yoe, wrote the book The Burman, His Life and Notions – generally regarded as the 19th century’s finest work on Burma, and one which remains frequently consulted to this day.

Despite its altitude, Taunggyi no longer enjoys as mild a climate as it did in the past, and lacks the traditional atmosphere of settlements around the lake itself. If you come here at all it will probably be to visit the five-day market, visited in large numbers by the region’s hill tribes who flock here to buy and sell home-grown fruit and vegetables, and to stock up on household essentials imported from China.

In the city centre, close to a monument to Bogyoke Aung San, stands the small Taunggyi Museum (also known as Shan State Museum, Mon–Fri 9.30am–4.30pm; charge), worth a look if you’re interested in the region’s hill tribes, with displays of 30 or so costumes from Shan minorities.

Pa-O guide at Kakku Pagoda.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Kakku

The archaeological site of Kakku 3 [map] (also spelt “Katku”), 42km (26 miles) south of Taunggyi, comprises a forest of ancient stupas rising in spectacular fashion from a valley on the far side of the mountains from Inle Lake. There are said to be 5,257 individual pagodas here, arrayed in rows. Some date from the Bagan period (11th to 13th centuries), but others may even have their origins in the distant Mauryan Empire of the Indian ruler, Ashoka (304–232 BC). Little else is known about them but closer examination reveals a remarkable wealth of decorative detail.

Tip

Hotel and guesthouses in Nyaungshwe can arrange a car for trips to Kakku. The round-trip fare costs around US$40–60 in a vehicle seating four to six people.

Kakku lies on Pa-O land, so in addition to the entry charge you have to employ a local Pa-O guide to show you around. Book ahead at the tourist office in Taunggyi if you’re not on a pre-arranged tour.

Kalaw street scene.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Kalaw

Perched on the western rim of the Shan Plateau, Kalaw 4 [map], 70km (44 miles) west of Taunggyi, was once a favourite hill-station retreat for British officials and their families during the hot season – little wonder, considering its beautiful setting amid bamboo groves, orange orchards and pine woods. In common with mountain retreats in the Himalayan foothills of India, the town retains a faded colonial atmosphere, and a noticeably cosmopolitan mix of people descended from the Sikhs, Tamils, Nepalis and Indian Muslims who were drafted in as a labour force in the late 19th century. In addition to this cultural legacy, the British left behind some attractive gardens and Victorian buildings, but most visitors come here to trek in the surroundings hills. Kalaw also hosts one of the region’s most vibrant five-day markets, for which minority people descend en masse from the hills dressed in traditional costume.

Trekking from Kalaw

Innumerable trails thread through the green, forested hills around Kalaw, but the ones most commonly followed by foreign visitors are those leading to Inle Lake. Passing numerous Buddhist pagodas and villages of the Palaung, Danu, Pa-O and Taungyo tribes, the routes take between two and three days to cover, and usually wind up at the ruined stupa complexes of Inthein, from where you’ll be transferred to your hotel by motorboat. The trails are not all that physically demanding, but standards of comfort vary greatly in the village houses and monasteries where you’ll overnight along the way. Bring a flashlight and plenty of insect repellent. Treks can follow stretches of surfaced road, winding over ridges into lush valleys, across patchworks of tea plantations, tanaq-hpeq bushes (whose leaves are used for rolling cheroots), orange groves and rice paddies, so you’ll need footwear that can cope with a variety of terrain, as well as warm clothes for those chilly evenings in the hills.

Green Hill Valley Elephant Camp

A worthwhile excursion from Kalaw, especially if you’re travelling with children, is the delightful Green Hill Valley Elephant Camp (www.ghvelephant.com). This privately run centre, set in a beautiful conservation area a 45-minute drive out of town, cares for sick and retired forestry elephants, using profits from tourist visits to protect traditional local lifestyles and some 60 hectares (150 acres) of woodland. Visitors can undertake treks through the surrounding countryside, as well as getting the chance to feed and bathe the resident pachyderms under the watchful eye of their mahouts, and perhaps also take a short elephant ride.You can do your bit for local conservation by joining a tree-planting programme.

Hill-tribe etiquette

Trekkers should follow certain guidelines to protect hill-tribe sensibilities and promote good relations. Use common sense, accompanied by a friendly smile. Always ask permission before entering any building or before taking a photo. Avoid photographing old people, pregnant women and babies. Avoid touching, photographing or sitting beneath village shrines. Avoid stepping or sitting on doorsills as, according to custom, this brings bad luck. Avoid changing clothes in public and always dress modestly. Avoid public displays of overt affection and excessive wealth. Always try to speak calmly and quietly.

Posing for a group photo at the entrance to Pindaya caves.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Pindaya

Pindaya, a three- to four-hour drive northwest of Nyaungshwe (Inle Lake), is famous across Myanmar as the site of the extraordinary Shwe U Min Cave Temple 5 [map] (daily 6am–6pm; charge), a huge, convoluted complex of limestone grottoes crammed with around 9,000 Buddha images. Varying in size and style, the figures were mostly installed between the 16th and 18th centuries, and are made of gold, silver, marble, lacquer, teak and ivory.

The caves honeycomb a steep hillside rising above Pone Taloke Lake. They are accessed via a network of covered stairways and lifts leading to ornately gilded and decorated entrance pavilions. It’s obvious from the start that the Buddha statues are very much objects of active veneration: worshippers young and old bow before them, offering flowers and incense in clasped hands to honour the principles of kindness, compassion and tolerance which the images embody.

The most revered cave is the Antique Pagoda, built by King Sridama Sawka more than 2,000 years ago, comprising myriad golden Buddhas sitting in red niches stacked one above the another.

Padah-Lin Caves

Situated near the village of Ye-ngan, northwest of Pindaya, are the Padah-Lin Caves 6 [map] (open daily), Myanmar’s most important Neolithic site. Countless chips created by the hacking away of stone axes have been found here, leading archaeologists to believe the caves were a site of tool- and weapon-making in prehistoric times. In one of the caves, traces of early wall paintings can still be seen. Images of a human hand, a bison, part of an elephant, a huge fish, and a sunset are clearly visible.

Eastern Shan: Kengtung and Beyond

The far east of Shan State is one of the most remote corners of Myanmar open to foreigners. Separated from the rest of the country by a convoluted mountain range, it has retained strong cultural affinities with neighbouring Thailand and Laos, from where its original settlers migrated with the Chiang Mai Dynasty in the 13th century. Opium has long been the region’s principal cash crop, and protracted armed struggles for control of the narcotics trade have until recent years kept much of the so-called “Golden Triangle” off limits to outsiders.

East from Taunggyi, the rough but scenic Highway 4 crosses endless green ridges and river gorges to reach the capital of eastern Shan State, Kengtung (although sadly foreigners are not currently allowed to use this road and must fly into Kengtung). Between the 14th and mid-20th centuries, this route served as the major trade artery from China. Mule trains were used as transport; today, trucks have taken over but the link remains as vital as ever. The wares have changed over the centuries, however, so now instead of carrying tea, silk, camphor and walnuts from Yunnan and, on the return journey, lacquerware, silver and cotton, the modern commerce consists mainly of electronic goods and gemstones.

Kengtung

Kengtung 7 [map], the “Walled City of Tung” (although increasingly referred to as “Kyaingtong”), can seem rather unprepossessing at first acquaintance but improves rapidly on closer inspection. Laid out around Nawng Tung Lake, its medieval centre preserves a taste of old Asia, with a wealth of striking Tai Khün temples and markets frequented by the many hill tribes who inhabit the town’s rugged hinterland, including the Akha, Palaung, Kachin, Lahu, Pa-O, Shan and Wa.

In the centre is clustered a group of impressive 19th-century Buddhist sites. The Maha Myat Muni (“Wat Phra Jao Lung” in Shan/Tai) boasts an interior richly decorated with gold paintings on a red background; the even more spectacular Zom Kham (Wat Jom Kham) is a tall, gilded stupa topped by a golden hti that’s inlaid with precious stones. The monument is believed to date from the 13th-century migration from Chiang Mai’s Lanna Kingdom.

If you’re in Kengtung on its weekly market day, you’ll be treated to a feast of traditional costume. The Kung, who make up around 80 percent of the town’s population, wear horizontally striped green longyi, while women of the Lahu tribe wear black dresses with wavy patterns. The Lu are noted for their silver elbow and wrist bangles, but the most colourful are the Shan-gyi (Big Shan) women, in their yellow blouses, longyi, and green-striped headdresses. Local specialities on sale at the market include dried frogs and gingered quail eggs.

Northern Shan

While Inle Lake and its environs in the southwest are the main lure for travellers to Shan State, its northern region has attractions, too. The most frequented route is by rail from Pyin U-Lwin to Lashio (For more information, click here) via the Gokteik Viaduct, but you can also travel northeast by bus or car. Kyaukme is the first town of significance on the Pyin U-Lwin−Lashio road. Located 85km (56 miles) from the ruby, sapphire and jade mines of restricted town of Mogok in the northwest and the silver mines of Namtu in the northeast, Kyaukme is an active trading town for gem stones and jewellery and is a good place to shop for them.

Hsipaw

Hsipaw 8 [map], an old mountain valley town on the sinuous Tu River, was once the administrative centre for the state of the same name, one of nine formerly ruled by Shan princes. The town is noted for its haw, or European-style palace (not open to visitors), where the last sawbwa, Sao Kya Seng, and his Austrian-born wife, Inge Sargent, lived until the military coup of 1962, when the chief disappeared. He was later found to have been murdered by the regime – events described in vivid detail in Sargent’s bestselling biography, Twilight Over Burma.

Washing off water buffalo near Kalaw.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The majority of travellers who make it as far northeast as Hsipaw tend to come in order to trek to hill-tribe villages in the area, which are far less frequented and accustomed to foreigners than the country around Kalaw. For those travelling independently, trips of varying lengths, from day hikes to full-on expeditions lasting a week or more, may be arranged through local hotels and guesthouses.

Hsipaw’s main pagoda is the Mahamyatmuni Paya on Namtu Road, a much more modest complex than its namesakes further south but which is worth a visit for its immaculately painted stupas and gleaming brass Buddha statue, backed by a halo of flashing red and purple UV lights. Of more traditional interest is the old quarter just north of the centre where, among numerous antique wooden buildings, stands the Maha Nanda Kantha Kyaung, home to a Buddha made entirely from strips of woven bamboo.

For a great panoramic view over the town, head 1km (0.6 miles) south to Five Buddha Hill, where the terrace fronting the Thein Daung Pagoda offers a popular spot for a late-afternoon stroll, whence its local nickname, “Sunset Hill”.

Bawgyo Pagoda

A good time to be in Hsipaw is the full moon in March when the Bawgyo Pagoda, 8km (5miles) west of town, hosts its annual festival. Focus of the event is a spectacular stupa encased in a pavilion whose pillars, walls and domes are adorned in elaborate, multicoloured mirror mosaic – an amazing spectacle at night, when the complex is brightly lit.

During the festival, the temple’s four Buddha images are paraded around the precinct for pilgrims to make offerings of gold leaves. Members of the tea-growing Palaung minority people attend the Bawgyo festival in great numbers. Ox-carts trundle in with pottery, lacquerware, baskets and other handicrafts to sell, while vendors set up stalls offering food and games of chance. Lively pwe (shows) are held in the evening.

Buddha statues in the Pindaya caves.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The Bawgyo Pagoda images

According to local legend, a celestial being gave the 11th-century King Narapatisithu of the Bagan Dynasty a piece of wood out of which four Buddha images were carved. The king built the Bawgyo Pagoda to house the images for his people to worship. The rest of the wood was planted in the courtyard and it miraculously took root. The tree is still thriving and is considered sacred.

The four Buddha images are enshrined in the inner sanctum of the Bawgyo Pagoda and brought out only once a year during the March pagoda festival to allow devotees to venerate them and gild them with gold leaves.

For many years in the past, due to fears of robbery, the images were kept in the haw in Hsipaw for safekeeping. When it was time to take out the images for display, there would be a grand ceremonial procession, including a parade of elephants, to accompany the images back to the Bawgyo Pagoda.

During the reign of the sawbwa, the festival was the only time when gambling was allowed; it was also an important social event that brought together the Shan, as well as ethnic minorities from all over Burma, to display and sell their goods.

Lashio

The end of the Mandalay rail line is Lashio 9 [map], 100km (66 miles) away from the Chinese border. The last large town before the start of the historic Burma Road to China, which supplied the nationalist Kuomintang forces in World War II, it retains a frontier atmosphere, with a mostly Han-Chinese population. Devastated by a fire in 1988 and largely rebuilt in concrete and corrugated iron, the town is far from the prettiest in Myanmar. If you come here at all it will probably be en route to or from the airport – the nearest to Hsipaw. With time to kill, the most worthwhile option is the ornately gilded Thatana 2500-Year Pagoda, nestling amid the forest on a ridge top overlooking the centre. The town centre markets are also worth a browse, including the covered market between Lanmadaw and Samkaung streets and the night market on Bogyoke and Thiri roads. Just south of the centre look out too for the town’s attractive main mosque, rebuilt after the previous mosque was burnt to the ground during anti-Muslim riots in 2013..

Tip

Outside town, on the twin-peak summit of Taungkwe, is the Taungkwe Zedi, which offers great views of Loikaw. You can also visit the Lawpita Falls, which drive a large hydroelectric power plant.

Kayah State

Southwest of Shan is the diamond-shaped state of Kayah is the smallest in Myanmar. Until recently off limits to foreigners, the state can now be visited on government-sponsored tours, while independent travellers are also allowed as far as the state capital, Loikaw ) [map], now linked by railway and road to Aungban. Eight ethnic groups comprise the state’s inhabitants, among which the Padaung are the best known. Padaung women wear brass coils (often mistaken for rings) to make their necks appear elongated. In reality the heavy coils depress their collarbones, creating the illusion of a longer neck.

The best place to see the Padaung and other tribal groups such as the Bre, Yinbaw, Taungthu and Kayah, is at Loikaw’s Thirimingala market.