KEY 5:

IT IS ABOUT THE FOOD

I remember standing in the hospital cafeteria and thinking, There is nothing here for me. I can’t eat any of this, and then I looked around and—it hit me. Everyone runs on food. Every hug, every kiss, every page ever written is because of food. Without food there is no life. Everyone has to eat! I was so disconnected from the real purpose of food as nutrition and so focused on the emotional uses of food that I forgot that we all run on food. This was an important realization in my recovery and still strikes me as important.

—TA

Many people come to us for help and tell us they want to “get better,” but they don’t want to change the way they eat, gain any weight, or accept their ideal or natural weight. They want to gain insight into family dynamics, talk about their feelings, and discuss underlying issues, but they are very resistant and sometimes even unwilling to deal with or change their problematic food behaviors. We understand this. We both initially felt resistant to changing our eating behaviors in the beginning of recovery.

In Key 3 we explained that eating disorders are not about food because: a) food itself does not cause the problem; and b) there are many other aspects, other than issues of food and weight, that are involved in an eating disorder. The reality, however, is that it is possible to recover without ever gaining insight or dealing with underlying issues that caused your eating disorder, but if you don’t change your relationship with food, you cannot recover. Key 5 is devoted to understanding and changing your relationship with food.

Are You Too Rigid, Too Chaotic, or Both?

Most people with eating disorders struggle with issues of control around food and are either too rigid, too chaotic, or both. Those who restrict are too rigid, those who binge (whether they purge or not) are too chaotic, and if you do both, you vacillate between rigidity and chaos. Finding balance in your relationship with food is the goal and challenge. Rigid control over your food and weight actually leads to being out of control of your life. Your rigid rules and fears are actually controlling you, rather than the other way around. If you binge, you most likely feel chaotic and long for some degree of control. You may find that you do not easily fit in one category, or stay on one end of the spectrum, but rather vacillate between rigidity and chaos. People often slide between the diagnostic categories from one type of eating disorder to another. Regardless of what kind of eating disorder you have, you are not eating or living in balance. Your life has become driven by thoughts and beliefs regarding what you think you should look like and what you think you should do to make that happen.

Carolyn: At some point early on in my work as a therapist I realized that all my clients had tenets related to food and weight that they were trying to live by, even though they had never formally written them out or told anybody. After hearing these over and over I compiled a list called “The Thin Commandments” of these rules or beliefs clients had reported to me over the years and published it in my book, Your Dieting Daughter (1997). Look over the list and see which ones seem familiar.

The Thin Commandments

• If you aren’t thin, you aren’t attractive.

• Being thin is more important than being healthy, more important than anything.

• You must buy clothes, cut your hair, take laxatives, starve yourself, and do anything to make yourself look thinner.

• Thou shall “earn” all food and shall not eat without feeling guilty.

• Thou shall not eat fattening food without punishing oneself afterwards.

• Thou shall count calories and fat and restrict intake accordingly.

• What the scale says is the most important thing.

• Losing weight is good, and gaining weight is bad.

• You can’t trust what other people say about your weight.

• Being thin and not eating are signs of true willpower and success. (pg. 13)

Food Rules

Aside from beliefs like The Thin Commandments, most people with eating disorders have developed what we refer to as “food rules.” Even if you have not written them down, spoken them out loud, or formally considered them rules, you likely hold certain beliefs about what you should or should not do with food. Some of our clients immediately recognize what we mean when we ask about their food rules, but others need examples and time to think about what rules they are actually following. For example, you might have a rule about not eating anything after 9:00 p.m., not eating dessert, or that you must purge if you eat something “fattening.”

The reason you have developed food rules or other rules regarding your weight is to provide you with a way of “keeping yourself in line.” Rules can give you a sense of control and assurance that nothing bad or unexpected will happen. Food rules are objective, measurable, and they limit choice, making you feel “safer” when you are tempted or anxious around food. It is easy to believe that these rules will alleviate the mistrust you feel about your own appetite, desires, and decisions. If you believe you cannot trust yourself or your body, it makes sense that you would develop rules, whether consciously or not, to keep you in line.

Writing Assignment:

What Are Your Food Rules?

Take a moment to write out your food rules in your journal. Write down as many as possible, the reason for each rule, and what you think it does for you. Write the rules as well as your beliefs, if you know them.

Next, it is important to evaluate your rules. Look over your rules one by one. For each rule ask yourself, how did I come up with this rule? Do I plan on following this rule forever? What happens if I break the rule? The following questions will help you evaluate and reconsider your rules.

• Is this rule based on facts or fears?

• How does this rule inhibit relationships? How does this rule enhance them?

• Do other people have to follow this rule to be OK, and if not, why do I?

• Does this rule allow for any flexibility, for unusual situations like being sick, or having an especially active week?

• Does this rule allow for special occasions or holidays?

• Would I tell anyone else to follow this rule? Why or why not?

• What am I giving up by following this rule? What am I gaining?

• What would it take for me to give up this rule?

It’s important to see your food rules for what they are, how they limit your life, and how they make you feel. To work at getting well you need to begin to challenge your rules, let go of them, perhaps even adopt healthier ones, and develop a more satisfying relationship with food.

Changing Your Relationship With Food

Following food rules or engaging in eating disorder behaviors can temporarily feel empowering and seem helpful. The problem is that this does not work in the long run, because even if you gain a sense of control, it is only an illusion and temporary at best. You probably feel afraid to let go of your rules and your behaviors, or change your weight, because you fear what would happen. Change can feel scary. You don’t know what will happen, and you aren’t sure if changing will be worth it. The fact that we and countless others stay recovered is a testament to just how much better it really is on the other side of an eating disorder. If this was not the case, we would have returned to our eating disorders and would not be trying to help you.

Letting go of eating disorder behaviors and finding balance with your food takes awareness, practice, and of course, patience. Even if you feel attached to your behaviors and resistant to changing them, we encourage you to be as open as possible to what we have to say. Nobody except for you can decide whether you want to change or not.

In order to begin changing your relationship with food, it is important to look at your current behaviors, so you can be honest with yourself about what you are doing and what you need to work on and change. Even though you might not be sure that you want to let go of a specific rule, belief, or behavior, the fact that you are reading this book suggests you want something to be different, or at least you are thinking about it. The following writing assignment will help you start looking at goals you have and thus changes you might like to make.

Writing Assignment:

What Are Your Food Goals?

Whether or not you feel ready or able to achieve your goals, it is helpful to have them written down so you are clear about them and are able to revisit them regularly. Take some time, try to be honest, and set aside your fears for now. Answer the following questions as if you are not afraid of losing control or gaining too much weight or being deprived, or any other fears that might come up for you.

• What would you like to do with food that you currently can’t do (e.g. eat a variety of foods, eat without feeling anxious or guilty, eat with friends, go to restaurants, eat things you really like)?

• What behaviors would you like to stop doing with food, but currently can’t stop (e.g., counting calories, eating all night, cutting up food into bits, only buying fat free food, bingeing)?

• Describe what you think a healthy relationship with food looks like. How would you would like your relationship with food to look if you did not have to worry about your weight?

• Compare your two answers. Referring to your journal will help you stay connected with your intentions and goals as you explore the ideas in this key and begin to work toward change.

You may have so many goals that it seems overwhelming, or you don’t know where to start. We suggest you pick a few to start with and focus on those until you make progress, and then you can move on to other ones. Even if you are willing to choose one goal to start with you are on the right path.

It might take a while to unravel the issues involved in both the development and deconstruction of some strongly held beliefs and ingrained behavior patterns. You developed your behaviors over time to help yourself in ways you might just be starting to understand, or maybe do not yet understand at all. To break your patterns you will need to start challenging your food rules. A good place to start is by looking at your rules about “good” foods and “bad” foods.

Letting Go of “Good” and “Bad” Food Labels

Writing Assignment:

Good and Bad Foods

Many people follow some kind of rule about what are considered “bad” or forbidden foods and what are “good” or allowed foods. The list of good and bad foods can change based on the latest and most popular diet being promoted. If you have an eating disorder, you most likely have this list in your mind. Make a written list of the foods you consider good and bad and add any reason or information that makes you think this. Examine your own evidence or lack of evidence that supports your beliefs.

We have very important news for you: as far as your weight is concerned, there is no such thing as a “good” or “bad” food. If you label a food “bad,” it usually means you think it has too many calories, not the right kind of calories, or is a food that makes you feel out of control, all of which will supposedly lead to weight gain. If you label a food “good,” it most likely means the food is low calorie, and/or you hope it will help you lose weight or prevent weight gain. The list of what is considered good food and bad food can change based on the latest popular diet being promoted in the media. One year, fat is bad and the next year, carbohydrates are bad. We are well aware that different foods contain different nutrients. Some foods are more nutrient-dense than others, and some foods, such as certain kinds of fats, are better for your health than others, but as far as your weight is concerned, a calorie is a calorie. Weight is determined by calories consumed versus calories burned. No food is bad or should be forbidden. Your body does not gain weight from 300 calories of yogurt and fruit any more or less than it does from 300 calories of pasta and meatballs. This is a very hard belief to break down, so you may need to read that last sentence over and over. After you read this key, we hope you will be able to fight against your eating disorder self more effectively when it tells you certain foods are bad or will make you gain weight. We are also going to introduce you to a philosophy of eating that is simple really, but at first you will find it difficult to do, because it will be far from what you are doing now and you may not trust it. You may initially have to follow a meal plan or a more specific structure than the one we are going to present you with now (more to come on this) but we will start by teaching you the end goal so you can have it in your mind.

Conscious Eating

Conscious eating is the ultimate goal for you and your relationship with food. When we use the term “conscious,” we mean using knowledge and awareness. When you practice conscious eating you place an emphasis on awareness of your body signals, incorporate general education about nutrition, take into account any relevant health information, and eat the foods you truly enjoy. Some of our clients have misused nutrition information or “health food” doctrines as a way to justify restricted eating. Eating only raw foods or organic foods or vegan foods might have some health benefits for a person without an eating disorder, but if you have an eating disorder you cannot afford to hide behind these kinds of nutritional dictates. Until you recover from your eating disorder, such rigid extremes have no place in your life and will continue to keep you in an unhealthy, good food versus bad food mindset. As long as you have an eating disorder, there is no way to justify that you are doing this kind of eating for health reasons. The health consequences of your eating disorder far outweigh those of eating cooked food or non-organic produce. Even well after recovery we do not recommend such rigid eating standards that would undermine conscious eating. Eating consciously is a powerful alternative to restrictive food rules and chaotic eating disorder behaviors. Eating consciously helps you decide when, what, and how much to eat, and ultimately allows for a healthier relationship with food and your body. Conscious eating is a shift in thinking and takes attention and patience to learn, but eventually becomes second nature and takes no effort. Feeling doubtful? We don’t blame you a bit. We know it might be hard to believe that there is a way of eating that will help you heal your eating disorder and allow you to feel safe around food and maintain an appropriate weight.

Becoming A conscious Eater

Since it takes knowledge and awareness to be a conscious eater, we provide guidelines that explain what kind of knowledge and awareness we mean. We trust and follow these guidelines and we have seen them work with our clients. At first some of the guidelines or how you can follow them may be confusing, but as you read through the key you will gain a more thorough understanding. We recommend discussing the following concepts with a dietitian who has experience treating eating disorders for more information, or to enhance our conscious eating philosophy and help you with this process.

Conscious Eating Guidelines

1. Be conscious of your hunger. Eat when moderately hungry; don’t wait until you are famished.

2. Eat regularly. Do not skip meals, and if possible, don’t go over four hours without eating.

3. Allow yourself to eat all foods (unless you are allergic or have some other serious health issue).

4. Eat what you want, while also being conscious of how foods make you feel, what you have already eaten, and relevant health issues (for example, candy may not be a good conscious choice if you have diabetes or if you haven’t eaten any protein all day).

5. All calories are equivalent when it comes to weight (that is, a calorie is a calorie).

6. For meals, eat a balance of protein, fat, and carbohydrates. Your body needs all of these to function properly and efficiently. Deprivation of foods or nutrients leads to physical and psychological problems and can actually trigger eating disorder behaviors.

7. Stay conscious of your fullness and your satisfaction. You can eat a lot and not be satisfied. Texture and taste of food is important for satisfaction and eating enough is important so your body registers the experience of being comfortably full. The goal is to feel full and satisfied, but not physically uncomfortable in any way.

8. If you do overeat (which is normal to do sometimes), reassure yourself that your body can handle the excess food if you simply get back on track. It is OK to wait until you are hungry before eating again, but don’t wait too long.

9. Enjoy food and the pleasure of eating. At times, enhance your eating to dining, using candles, nice dishes and flowers on the table.

10. Make conscious choices to avoid foods that make you physically feel bad after eating them.

As you can see, all of the guidelines are specific ways to help you be conscious and present when eating, knowledgeable about your choices, and aware of how your body feels. Developing a healthy, balanced relationship with food (not too restrictive or permissive) is an empowering and life-altering experience. The Conscious Eating Guidelines will help you find balance in your relationship with food. Even if this is not your first step in terms of changing your relationship to food, know that you can get there and commit to yourself that you will give it a try.

Putting the New Guidelines into Practice

When you are ready you can begin to put our new eating guidelines into practice. The “conscious” part is the core and will make all the other parts possible to follow. Some people resist the idea of adopting what they think of as even more guidelines. Many clients tell us they are already too conscious about everything they eat, eliminating every food they believe to be “bad” or “unhealthy.” Others are very self-conscious and worry about what people will think or say about their food choices. Many clients who are overweight feel self-conscious about eating certain foods in front of others. They fear judgment or comments like “how could she be eating that?” We understand how hard it is to ignore or not care about what others think, but it is really important that you give yourself permission to eat all foods. There are also those who are unconscious when eating and lose touch with body signals, hardly taste the food they consume, and have little awareness of how much they are eating. The goal of conscious eating is to be conscious enough to stay connected to your bodily sensations of hunger and fullness, conscious enough to be aware of other people and the conversation around you, and conscious enough of health and nutrition information to make appropriate choices without depriving yourself.

When the brain is hijacked by an eating disorder your ability to eat consciously is impaired. If you have an eating disorder, you are probably no longer eating according to your hunger and fullness, and may not even recognize these cues. Most likely, you have been ignoring or overriding your body signals for a long time. Neglecting your hunger signals can alter your sensitivity to them and eventually make them difficult to detect. For example, if hunger is something you have tried to control, it might now trigger stress or anxiety rather than simply cueing you to eat. If you generally restrict your food you might experience hunger as a “good” feeling, because you feel powerful or successful when you deny yourself. If you overcome or resist your hunger it might feel like confirmation that you are “in control” or perhaps losing weight. If you are someone who binge eats, hunger may trigger fears of deprivation, or may have come to represent a variety of feelings, even shame. Responding to hunger by eating often makes people think they are weak or failing somehow. If this is true for you, you have forgotten that by responding to hunger you are taking care of your body and your energy level and optimizing the functioning in your brain and what we know is important to you—your metabolism. Feeling full can also be problematic and can signal feelings of panic, irritability, and remorse instead of satisfaction and contentment.

Having an eating disorder transforms normal, healthy body signals into stressful, anxiety-provoking feelings. Most people with an eating disorder end up abandoning body signals altogether and begin relying on external cues like dieting guidelines, food rules, or calorie counting. In fact, your decisions about when, what, and how much to eat are probably based on the kind of beliefs expressed in The Thin Commandments rather than from your body. Luckily, you can rebuild trust in your body as you practice conscious eating and start listening and responding to your body again. The great thing about conscious eating is that the body is quite adept at knowing and letting you know when, what, and how much you need to eat without risk of any mental or physical harm.

There are going to be obstacles at first, but if you don’t give up and keep working at it, you will get there. If you are underweight or very restrictive, you might find yourself full very quickly due to slowed digestion, and because your stomach is not used to the sensation of having a normal amount of food in it. Also, if you are highly anxious about eating, you might feel hunger or experience a sensation of fullness after eating only a small amount. If you have been bingeing, you might not be able to feel fullness after eating a normal amount of food. All of these conditions will resolve themselves and return to normal as you begin to normalize your eating. You may have to initially use a specific meal plan to help normalize your body and retrain yourself to feel hunger and fullness. The thermostat that tells us the endpoints, hungry or full, is broken and it is reset in the process we label recovery. Following a meal plan retrains your mind and body to think about and experience food differently. A meal plan helps you reestablish patterns by actually rewiring your brain and body signals establishing healthy habit patterns that then shape your future decisions regarding what and when to eat. Awareness is achieved by mindfulness practices. Meal plans are an effective first step for many clients and will be discussed in more depth later in this key.

If you are still feeling skeptical about conscious eating, you may need to gather your own evidence before you trust that these new guidelines work. We often ask our clients to agree to try this approach for just one day, to see how it feels. You can also take the guidelines to a dietitian to discuss your doubts, fears, and any questions you may have. The more you are able to follow conscious eating, the more trust you will develop in yourself and your body.

Keeping Food Journals

A food journal is a way to gather data on what you are currently doing with your food. As you begin to make changes, your food journal will help you to see how things are going for you. After only a couple of days of keeping a food journal, it is easier to recognize the areas where you need more work. Many clients resist the idea of keeping a food journal. Some report feeling more anxious when having to write down their food or see the foods they listed. Others admit they don’t want to face the truth about what they are doing with food. Still others feel overly controlled and then rebellious just writing things down. Whatever your reasons may be for not keeping a food journal, there are better reasons for working through your resistance and trying it out. To change a behavior you need to be clear about the behavior you want to change and be able to track your progress in some way that is measurable. Your food journal should consist of a series of five categories where you will be recording information.

Each entry in your food journal should include:

• The time you ate.

• The type of food you ate.

• The approximate amount you ate.

• Your hunger level before the meal.

• Your fullness level after the meal.

• Any feelings or thoughts you had about eating or anything else.

• Whether or not you felt the urge to purge after eating, and whether or not you gave in to that urge.

Please see the appendix at the end of the book for a sample of a food journal.

The Hunger Scale

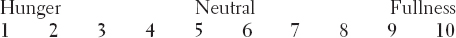

Reconnecting with your own hunger and fullness is an important part of a food journal and an important step toward conscious eating. In each entry of your food journal, you record the amounts and types of foods you have eaten and rate how hungry you felt when you started eating and how full you felt when you finished. The hunger scale is a continuum which starts at 1 for extremely hungry and ends at 10 for extremely full. The following is a brief description of each number:

1. Extremely hungry, lightheaded, headache, no energy.

2. Still overly hungry, irritable, stomach growling, constant thoughts of food.

3. Hungry for a meal, sensing hunger, thinking about food and what would be good to eat. This is the ideal hunger level for eating a meal.

4. A little bit hungry, a snack would do, or making plans for eating pretty soon.

5. Neutral: don’t feel hungry or full.

6. A little bit full, not quite satisfied, have not eaten enough.

7. Satisfied and comfortably full, could get up and take a walk. This is the ideal target for conscious eaters to stop.

8. A little too full, happens sometimes, wait until hungry again to eat, but not too long.

9. Overly full, uncomfortable, like what happens on holidays, try to learn from this.

10. Extremely full, painful, likely after an episode of emotional eating or binge eating. Very physically and emotionally distressing.

Over time, you will find using a food journal helps you become aware of how it feels in your body when you are satisfied, as well as when you are a little hungry, too hungry, a bit too full, or overly stuffed. You will be able to see how much time lapses between your meals, which can help increase your understanding about why you may have become too hungry and when you might need to add a snack. As time goes on, you will see patterns emerging. For example, most people notice that if they allow themselves to get to a 1 or 2 on the hunger scale, they are more likely to eat to an 8 or above later. It is harder to stop eating at the appropriate level of fullness when you start off overly hungry. Many of our clients tell us they hardly eat during the day if they have a social event to attend at night. They believe not eating all day will help them feel less anxious about eating normally when out socially. Other clients undereat during the day to “balance” the overeating they are afraid of engaging in at night. What both groups don’t realize is that being overly hungry at a meal is a big set-up for overeating, and anxiety around food is increased rather than decreased. People with eating disorders tend to find themselves at the extreme ends of the hunger scale more often than not. The goal is to find the balance, and not let yourself get too hungry or too full.

It is important to note that some people have a very difficult time with the hunger and fullness scale. Some report that they just cannot seem to get in touch with the “feeling” of hunger, much less a certain level of hunger. Others report that their hunger is erratic with no pattern or explanation or it varies wildly according to their mood or menstrual cycle or the weather. Still others get caught up in the subjectivity of it all, trying obsessively to figure out the exact number that fits them before and after each meal. Knowing your hunger level on a scale from 1 to 10 is not critical. What is critical is to not let yourself get too hungry or too full. As dietitian Ralph Carson says, “When talking about hunger and fullness I like to use the analogy of filling our car with gas. The important thing is, don’t let your car run out of gas and don’t overfill the tank once it’s already full.”

Food journals can help increase your overall awareness and help you set goals in specific areas. Eventually you will learn to use your knowledge and awareness to develop new habits and patterns of eating that will help you normalize your weight and facilitate recovery.

Writing Assignment:

Tuning into Your Hunger and Fullness

Tune in for a moment right now and see if you can determine, using the scale from 1 to 10, how hungry or full you are right now. You may not be sure, but do the best you can to estimate. When you start keeping a food journal you will be tuning in several times a day, and you will get better and better at gauging your hunger and fullness.

Take one day to fill out a food journal and record your hunger and fullness every time you eat. Don’t worry if this is difficult at first. It takes practice. Try talking it over with someone or ask a friend to try to do a hunger and fullness scale also. It might be fun to do it together with someone.

We tell our clients to continue to use the hunger and fullness scale until they feel they can easily tune in to their hunger and fullness. Knowing your hunger and fullness is an important step toward becoming a conscious eater. We recommend using a food journal for as long as you find it helpful. You will need to see if using the food journal and the hunger scale is a method that works for you.

Meal Plans

Some people who come to see us are so lost, afraid, or out of control with their food that they want or need a specific meal plan. A meal plan can be a useful first step toward beginning to eat more or regain control over behaviors such as bingeing and purging. A meal plan is a structured way of determining, ahead of time, what and how much you are going to eat each day. Meal plans can be set up and adapted in a variety of ways. Many of our clients resist having a meal plan, while others are desperate for one in order to feel “safe” and make sure that their eating habits are accounted for and not slipping out of control.

If you need to gain weight, a meal plan will most likely be necessary because: a) you aren’t in touch with hunger and fullness signals or they are inaccurate; b) eating according to hunger and fullness does not facilitate weight gain; c) you are probably too afraid to eat what you really want or what you need in order to gain weight; and d) you probably have lost track of what is an appropriate serving or what a real meal looks like. For all of these reasons you may need more structure. You might also need a meal plan because you are too afraid and entrenched in your current eating behaviors to try anything new and make any solid changes without specific structure and support. A meal plan will provide guidance and a sense of control around your eating and help get you started.

Since there is no way for us to know the foods you like, how much you should be eating or what foods to include in your meal plan, or many other individual considerations, help from a dietitian or other professional who specializes in the treatment of eating disorders is recommended. What we can do is introduce you to the basic principles of a meal plan and offer some helpful suggestions.

Making a Meal Plan

To make a meal plan, you come up with a written list of what you plan to eat for breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snacks. Meal plans can vary and range from being very general, such as listing how many calories you have to consume a day, to stating how many servings of protein, carbohydrates, and fat you need for each meal and then filling it in with your choices each day, to a very specific plan with the foods and portion sizes. (For example, Breakfast: 3 scrambled eggs, ¾ cup melon, and a bagel with 2 tsp of butter and 2 tablespoons of jam.) We don’t usually advocate these kind of exact portion sizes. We prefer using hand estimates such as 1 cup = a fist, 3 ounces = palm of hand, and a tablespoon = a large thumb. The idea is to get in the ballpark of portion size estimates because exact amounts do not matter. Whatever your meal plan looks like, it should be a step toward lifelong eating and recovery, not a “diet.” When working with meal plans, start where you can and then gradually increase or decrease the variety and frequency of your eating according to your own goals and needs. The idea is to create a balanced meal plan with the appropriate amount of calories to help you move toward recovery. Both of us started with meal plans. Our own personal experience and that of our clients has shown us that meal plans can provide the structure, containment, and safety needed to make difficult changes and let go of eating disorder behaviors. If you decide to try a meal plan and find yourself feeling overly controlled and rebellious as a result, you might need the freedom and flexibility offered by following the Conscious Eating Guidelines. If you are not yet ready or willing to go to a dietitian or eating disorder professional, find someone else in your life who can offer you the necessary support and accountability. Voicing your commitments or intentions to another person increases the likelihood that you will follow through. Meal plans are often a helpful first step in the recovery process and a bridge to the ultimate goal of conscious eating. If you would like to read more about the concepts we have outlined in this key, refer to the Resources section at the end of the book.

Personal Reflections:

Gwen: Early in my recovery, I needed to follow a meal plan. I was out of touch with my body, my hunger and fullness, and what was the appropriate amount to eat. I needed specific guidance and structure. Although I was initially afraid and resistant, it was actually easier to have a meal plan and not have the stress of making decisions in the moment. The meal plan helped me gain weight in a way that didn’t feel out of control, get back to a regular schedule of eating, and incorporate a variety of foods back into my life. As I continued to get better I was able to follow my meal plan easily without any anxiety. Over time, I started to feel like my meal plan was another “diet” to follow, and I found myself feeling too con-fined and limited by it. I was afraid to branch out, but I wanted to eat more freely, and I had good role models encouraging me to do so. Fortunately, following the meal plan and eating regularly had helped me reconnect with my hunger and fullness and prepared me to begin using these signals to guide my eating. Navigating this next step in my recovery was still very challenging. Sometimes I was still hungry or not satisfied by what I had eaten, but I was afraid to eat more, or eat something different. I found a dietitian who explained a concept called “Intuitive Eating,” which she said I was ready for. I could feel my anxiety and anger begin to surface as I listened to her explaining what sounded like a description of how to eat “normally,” as if it was so simple. She sensed my resistance and suggested I try it for just one day. Trying it one day sounded reasonable to me so I agreed. It felt very strange and I didn’t trust myself much, but at the end of just one day, I felt better both physically and emotionally, and was thus encouraged to continue working with this approach. After a few more days of using my knowledge, the experience I had gained on my meal plan and my awareness of hunger and fullness to make decisions about eating, I knew I had discovered the tool for the final step in healing my relationship with food. This new way of eating gave me the freedom with food I wanted but feared, and the guidelines made sense and provided the sense of safety I needed. I slowly started to trust myself more and believe it was OK for me to eat all foods. There were times when I ate more than usual or ate when I wasn’t hungry. The process took some time, but eventually, for the first time ever, I was eating freely, enjoying foods I had been avoiding for years, and maintaining my weight. It felt amazing.

Learning to eat in this way helped me to turn an important corner in my recovery. For the first time in many years, I trusted myself to know what to do with food without using outside information for guidance.

Carolyn: When I had anorexia there were no dietitians around, no books on eating disorders, and no places to find guidance on what to do about my eating and weight. The first professional I went to for help had never even seen anyone with an eating disorder, much less worked with anyone with the illness. He asked me to drink a soft drink in front of him so he could see what I would do. I did not go back. So the second person I saw, a female therapist, who had also never seen or heard about eating disorders told me I should eat by myself, if eating made me feel guilty. I knew if I did that, I would eat even less. After a lot of stops and starts, fear and resistance, I knew I had to find a way to stop my weight loss. I ultimately had to come up with ways to help myself begin to eat more normally again. I offer readers a few tips that helped me along the way.

I started saying to myself that “Full is not the same thing as fat.” I would say it over and over again to calm myself when I would eat and begin to think I was fat. I stopped looking in the mirror when I got dressed, because I would see myself as too fat and want to not eat what I had planned. I bought loose, baggy, but nice clothes so I wouldn’t notice the weight gain as much or the feeling of my stomach after meals. When I would want to try a new scary food I would start by having a very small portion of it, like half a piece of pizza or even less, and then eat other safe food to make up the calories. I did this to reassure myself that nothing bad would happen and I would not be fat the next day. Over time I would get to the point of having a whole piece of pizza and eventually two pieces, slowly replacing my safe foods with this new one I really liked but had been afraid of. I did this many times with many new foods. I stopped looking up the calories in food. It was hard and numbers remained in my head for a while, but over time the automatic counting happened less and less, and eventually I stopped it completely. I went out with friends to help me be accountable for eating. I bought food I really liked and kept it in my house (I used to buy food I didn’t like because it helped me not eat much). If I wanted to eat a favorite food I had to also eat something that was important nutritionally. I did this because there were times when I would eat a cookie or ice cream and then be afraid to eat anything else. I wrote down what I ate and at the end of the day if I did not have enough food, I would make myself add more to get the total I had committed to. It took a long time for me to get to the amount of food where I gained weight, but doing it this way did help me eventually get there. I started having one day a week where I would go to a restaurant and order whatever I wanted. Again, this increased over time, to the point where I could always do it. And, finally, I stopped weighing myself. This was one of the most helpful things I did to recover, and it changed everything.

Accepting Your Natural Body Weight and Not Weighing Yourself

In order to repair your relationship with food and become a conscious eater, you will have to end your relationship with the scale. You will need to stop weighing yourself, stop making weight loss a life focus, and stop using a number to measure your self-esteem or gauge your self-worth. After all, the number on a scale is simply measuring “the force with which your body is attracted to Earth.” Remember, our definition of being “recovered” includes when you can accept your natural body size and shape and no longer have a self-destructive relationship with food or exercise. When you are recovered, food and weight take a proper position in your life, and what you weigh is not more important than who you are; in fact, actual numbers are of little or no importance at all.

Letting go of your emphasis on weight and weighing is so important to your success in changing your relationship to food that we put it in this key. We are fully aware that an eating disorder is the result of a variety of issues and that wanting to lose weight or change your shape does not cause an eating disorder. We also know that if you keep your weight goal as the driving force in your life, you will not be able to discontinue behaviors that interfere with your recovery.

Learning to Accept Your Natural Body Weight

A discussion about ideal, natural, or healthy body weight often generates a lot of anxiety, resistance, and confusion. Just as you are learning that your body can be trusted to give you accurate signals about hunger and fullness, you must also learn to trust that your natural weight is predetermined by your genetics and not by your desire. Many of our clients have a hard time accepting their natural body weight, not because they are overweight, but because they are not the weight they would like to be. If you are engaging in eating disorder behaviors to maintain your weight, you really can’t know your natural weight. Your body will send you signals (which are detailed below) when you are underweight. When you are at your natural weight, these signs will disappear. Many people have an idea what their natural body weight is and feels like, but we have listed some indicators below in case you are not sure.

Natural Weight Range, Physical Indicators

• Weight range is maintained without engaging in eating disordered behaviors (for example, restricting, bingeing, purging, or compulsive exercise).

• Having regular menstruation every month and normal hormone levels (as age appropriate).

• Normal blood pressure, heart rate, and body temperature.

• Normal blood chemistry values such as electrolytes, white and red blood counts, etc.

• Normal bone density for age.

• Normal levels of energy (not exhausted, shaky, or agitated all day).

• Normal or at least some sex drive.

Natural Weight Range, Psychological and Social Indicators

• Ability to concentrate and focus (reading, movies, work, school).

• Normal social life with authentic, in-person relationships (not just online).

• Decrease in or cessation of obsessive thoughts or food cravings or urges to binge.

• Can choose freely what to eat both when alone and with others.

• Can eat at restaurants, at friend’s houses, at parties, and on vacations.

• Does not have to eat according to certain rituals.

• No erratic mood swings.

Our bodies react negatively to being under or over our natural weight in spite of what we want or how we feel about it. It might be hard to believe, but even a few pounds below normal can cause abnormal physical and psychological changes. Starvation is a threat to survival and our bodies let us know when we are threatened. Even though the consequences are not as immediate, our bodies also give us signs when we are overweight in the areas of abnormal findings in blood pressure, lab values, hormones, energy, difficulty doing normal daily tasks, and many more.

Letting Go of Weight Loss as a Goal

One of the most difficult, yet important, shifts in your thinking will need to be letting go of weight loss as a goal. Orienting your focus toward making peace with food and your body instead of losing weight can seem impossible and feel disorienting. Many people with eating disorders have spent too much time, energy, and other resources struggling to lose weight, only to stay trapped in eating disorder behaviors. Here is a very simple explanation. If you have anorexia, weight loss is clearly inappropriate. In fact, your already low weight and your inability to acknowledge that or stop your drive to remain underweight is part of the diagnostic criteria of your condition. You have to let go of weight loss as a goal, or even maintenance of your low weight as a goal. If you have bulimia, then you will by definition be engaging in bingeing and then in some way compensating for it. Think about it—if you want to recover from bulimia, but you also have weight loss or not gaining weight as a goal, then what do you do the next time you overeat, or even just eat and feel bad about it? Your two goals (a) lose weight or avoid weight gain and (b) stop my bulimia, conflict with each other. If you keep weight loss or avoiding weight gain as a goal you will try to get rid of your food (purge) to avoid any weight gain. Here is one client’s reflection on giving up her goal of losing weight:

“The goal of losing weight has been the goal that I have worked the hardest at. That alone makes it hard to give up on. I don’t remember when it wasn’t the first thing on my mind and often the only thing. To let go of it feels like cutting off a part of me. I constantly have to remind myself that I don’t need to order the salad because weight loss is not my goal anymore. It is so ingrained that I keep forgetting. At first it felt disorienting. I realized that without weight loss as my goal, I felt really lost and empty. I began to see that life was passing me by. How did I get so self-absorbed and dull? I finally am at a place where I can truly say I want a better life more than I want to lose weight.”

—JR

If you place too much emphasis on your body or weight, you lose sight of the more important things in life. Even if you have gained excess weight or a physician has told you that you need to lose weight for health reasons, you are still better off putting the emphasis on your health and happiness instead of a number. The bottom line is this: if you are trying to lose weight, you cannot progress in recovery from an eating disorder, no matter what you weigh or what kind of eating disorder you have. We are not saying that it is never OK for anyone to lose weight—we cannot know if that would be appropriate for you or not. We are saying that for recovery from an eating disorder, your focus has to be on getting over any eating disorder behaviors and developing a healthy relationship with food. Some people may gain weight in doing this and some people may lose weight. In either case, it is your body returning to its proper natural state.

Writing Assignment:

Letting Go of Your Focus on Losing Weight

What would happen if you just decided to stop trying to lose weight? What did your eating disorder promise you if you reach this perfect weight? Do you think it is true, or have you noticed this to be true? How else has the desire to lose weight interfered with recovery? Write about what it might be like to focus first on recovery and then deal with any leftover issues regarding your weight.

Weighing

Weighing yourself is detrimental for the recovery process of any eating disorder. In surveys of recovered clients, they report that not weighing was one of the most important aspects to their success.

“Not weighing was instrumental in maintaining my recovery. I was a scale addict before treatment and would consistently return to my eating disorder behaviors, trying to manipulate the number on the scale. It is almost hard to believe that I do not weigh myself anymore and numbers never cross my mind. The scale no longer matters. It never helped me and for years interfered with my recovery. I will never ever weigh myself again for that reason. It is so freeing to not know. My identity is no longer based on a number. The number never got me anywhere; it only trapped me into not paying attention to my hunger or my body, which is all I really need to do to know what and when to eat. A scale never did and never can never give me that.”

—JD

Weighing yourself will impede your progress in a number of ways. We recommend that you stop weighing yourself and get rid of your scale. The three most important reasons are:

1. If you are underweight, seeing the numbers going up can be very stressful and compound your anxiety. Sometimes clients are on the right track and feeling positive about recovery until they weigh themselves and see the number. Weighing yourself can delay, prolong, and even halt recovery. We have never seen it help anyone. If it is necessary that your weight be monitored, have a dietitian, therapist, doctor, or someone else you trust weigh you without telling you the number.

2. If you binge and purge you might find that your weight goes up when you stop these behaviors. If this happens you might conclude that you need to keep purging or you will keep gaining weight, which is not true. Your body needs to adjust to having food inside of it and this adjustment period takes a little time. You may also retain fluid temporarily, which will resolve with normalized eating, or your weight gain might be due to necessary rehydration. Imagine a simple garden hose. Now image the hose is filled with water. It weighs more, but it has not gotten bigger. It does not look any different on the outside. Sometimes, when clients stop bingeing and purging they gain a little bit of weight during the first few weeks, but often lose it again when their bodies adjust to consistent eating. If you need to have your weight monitored, because you are at a dangerously low weight or are too afraid to simply stop weighing and need a first step, let someone else weigh you (more on this later).

3. If you are a binge eater or for some other reason are above your natural weight, weighing yourself can be detrimental to your recovery. For real recovery, healing your relationship with food is the goal, rather than losing a certain amount of weight each week. Using the scale as a measure of progress can backfire for a number of reasons. If you are successful with your goal of not bingeing after dinner or not turning to food when angry, but the scale doesn’t reflect back what you think it should, it is very easy to get discouraged and return to the behavior. Not seeing the numbers on the scale go down fast enough can make you give up. It often takes a while for the results of healthy behavior changes to show up on the scale, so weighing can be very misleading.

Regardless of the behaviors you are working on, or how much you weigh, get rid of your scale. If you need to check your weight for any reason, such as you need to know if you are gaining weight or you need reassurance that your weight is not going out of control, get someone else to do it. Consult with a dietitian, therapist, doctor, or someone else you trust who is willing to weigh you and tell you only whether you are on track or not. Have an agreed-upon goal and weight range and come up with the terms or conditions that indicate the need for giving you information. We recommend that you set a goal to reach and then be told when you get there, or if you are going in the opposite direction. If maintaining your weight is the goal, whoever is weighing you should tell you if you are maintaining or not. You are maintaining if you are within 2–3 pounds of your maintenance weight. We know it is hard giving up the scale and letting go of weighing yourself, but it is one of the most important behaviors to change if you want recovery. We no longer weigh ourselves, we teach our clients not to weigh, and you will see that it works for you too.

The following is just a sample of what clients have to say about weighing:

“Prior to treatment, I would weigh myself several times a day, and the quality of my day would depend on the numbers I saw. I felt that the numbers on the scale defined me. When I was fixated on a number I could not focus on anything else, including recovery. I would be upset if it was not what I wanted it to be, and it never was. I always thought I could lose more or had to not eat to keep it low. There was nothing good that ever came from weighing. It took time and trust to stop. I first let my dietitian weigh me for reassurance because I was afraid, but eventually I did not even need that. All I needed was to stop my eating disorder behaviors and follow my meal plan long enough to realize I would be OK and did not need a number on a scale to tell me anything.”

—JW

“Not knowing my weight the entire time I was at Monte Nido was incredibly helpful in weaning me off the scale. Once I left treatment there were a few incidents where I thought I had to know my weight and I thought I could handle it. Every time I stepped on a scale, whether the number was the same, higher, or lower than I expected, I became consumed with the number. I would go over and over it in my mind, wondering how to change it, why it was what it was, and how I could make it stay that way or get better. Weighing was always a mind trap and immediately affected my eating and my mood. I finally got it that I was fine without weighing and it was unnecessary and even disruptive to my recovery and my life. I continue to not weigh myself today and it feels good to know the number has nothing to do with who I am.”

—KM

Personal Reflections: Weighing

Gwen: At the height of my eating disorder, I was weighing myself several times a day. It felt like a compulsion that I had no control over. There were times I felt so desperate to know my weight that I would go to a drugstore and unwrap every scale and stand on it, pretending that I was a responsible consumer wanting to buy the best scale rather than the obsessed and desperate woman I really was. Making sure that I hadn’t gained any weight was the only way I could lessen my anxiety. It reassured me that I was still the same, still OK, and still in control of things. But the reassurance I got never lasted and within a very short time, I would feel the familiar urge to get on the scale again.

My morning weight would determine what kind of a day I would have, how I felt about myself, what I would eat, and what I would wear. If I gained even one half of a pound, my mood would spiral downward and I would isolate myself in self-reproach and become more restrictive. If I stayed the same weight, I was usually disappointed, but not devastated, depending on what I had done the day before. If I lost weight, I felt a warm jolt of joy, satisfaction, and calm. I felt more confident to go out into the world. I thought that if I lost weight, I would feel safe and free to eat what I wanted, but that day of relaxed eating never came. Instead, the more weight I lost the more anxious and insecure I became. If the number I saw didn’t reflect my hard work I would implode with anger, and sulk for days in a depressed funk, isolating from everyone while raging a private war against my body.

Carolyn and Gwen In Session

Carolyn: When I told Gwen that I did not tell clients their weight she was upset. Gwen was extremely anxious and untrusting. I wasn’t sure she would stay in treatment. I felt strongly that she needed to know that I understood her fears. I also felt that she needed to know that my philosophy of weighing was important to her healing and not just a rule I used to control my clients. I needed to work cooperatively with her and let her know I would not just blindly enforce a rule, but would try to help her understand and agree.

Carolyn: “I don’t tell people what they weigh because I have found that it does not help and, in fact, is information that they use against themselves.”

Gwen: “But that doesn’t seem right and I don’t understand how I use it against myself. I think I should have the right to know my weight.”

Carolyn: “Gwen, I am going to explain why I don’t tell people their weight and why I think it is harmful for you. I don’t weigh myself and my goal would be that you would ultimately decide not to weigh yourself, either. After this conversation, though, if I have not convinced you then I will tell you what you weighed today.” (I rarely say I will reveal someone’s weight. I did this because I was concerned about losing Gwen’s trust and after saying this, I could see Gwen’s body relax, as she realized I was really listening to her. )

Gwen: “OK.”

Carolyn: “First of all, I don’t think we should measure ourselves with a number on a scale. It never worked for me when I had my eating disorder or when I was trying to get better.”

Gwen: “But if I don’t know my weight I will be more anxious. Knowing my weight just helps me to reassure myself.”

Carolyn: “Really, can you tell me how it helped to reassure you before you came here? It does not seem like it was really helping at all.”

Gwen: “If I don’t see my weight I will be too afraid that I am gaining and will probably want to restrict even more.”

Carolyn: “You restricted your food the whole time you were weighing yourself. Let me guess, if you weighed more you restricted in order to lose it; if you weighed the same you restricted because you wanted to lose more or were afraid you might gain; and if you lost weight you restricted because a) it was working, or b) you were afraid to gain it back.”

Gwen: (smiling) “Actually, that is pretty true.”

Carolyn: “I won’t keep you in the dark. I am not saying you should just gain weight. We will set specific weight goals. For example, let’s start with a five-pound weight gain goal and I will tell you when you reach it. This is how I can protect you from sabotaging yourself. If you see the numbers you will want to interfere with the progress.”

Gwen: “Yeah, I have to admit what you are saying is true and no one has really explained it to me that way. But I think I am afraid I will gain too much.”

Carolyn: “But I already said that I would tell you when you made your first weight goal. You will know when you have gained five pounds.”

Gwen: “I don’t know. I just can’t get myself to say I don’t want to know the number; somehow I feel like I need to know.”

Carolyn: “Of course you want to know it. It is kind of like a smoker who quits but wants a cigarette. I wouldn’t expect you to say you want to gain weight, either. To get better you will have to do things that feel scary and that go against what makes you feel comfortable and “safe.” If you keep doing the same things you will not get better. Does that make sense?”

Gwen: “Yes, but it really stresses me out. It’s been 15 years of doing this and knowing my weight.”

Carolyn: “OK, how about this. I want you to take 24 hours to think over all I have said. Let’s talk tomorrow and see if you can come up with a good reason why you still want to know your weight, and how it will help you. If you can come up with even one good reason, I will tell you your weight.”

Gwen: “OK.”

Carolyn: The next day Gwen admitted that for the first time she felt truly understood. She felt hopeful that I might even be able to help her. She admitted that she had been unable to think of a reason why a specific number would help her and so I did not reveal her weight to her that day, or on any other occasion during the course of her treatment.

Final Thoughts

We hope you are on your way to taking steps toward becoming a conscious eater. Whether you are trying to listen to your hunger and fullness, make or follow a meal plan, give yourself permission to eat challenging foods, or find ways to cope other than turning to food, this will facilitate your recovery and free up your life. There are many overt eating disorder behaviors we have yet to address that are related to food and engaging in them will sabotage your recovery efforts and undermine the process completely if you are not able to stop engaging in them. There are also numerous behaviors such as exercising that might seem harmless to some people, but if you have an eating disorder you will need to explore these, as they could very well be sabotaging your recovery. Learning to change or let go of problematic behaviors is very difficult, but continuing them is not an option if you want to recover. Helping you change specific behaviors is the topic of our next key.