2 Developing Relationship-Based Approaches to Dementia Care

Learning objectives

By the end of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

- Critically consider the different relationship-based approaches to care and how they form a continuum of practice.

- Analyse the differences between individualised, person-centred and relationship-centred care.

- Examine how the use of biography can be used to implement relationship-based approaches to care.

- Investigate how you might implement person-centred and relationship-centred care in your practice.

Introduction

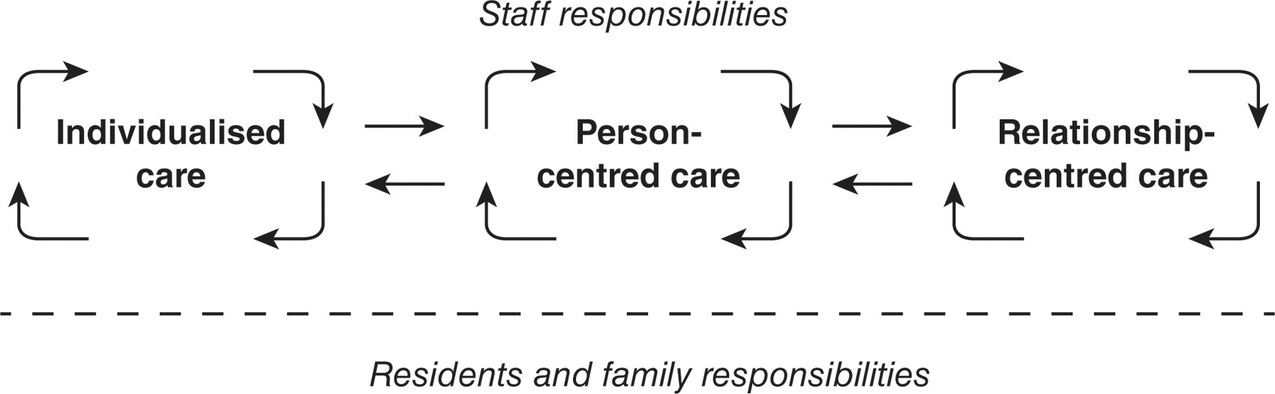

In the previous chapter we considered a range of myths that impact on the journey of the person with dementia and those important to them, from diagnosis through to death. The discussion demonstrated the value of healthcare professionals understanding how dementia affects a person and the potential for treatment and support as the condition progresses. Dementia has been likened to a journey that affects everyone differently and may take an individual to different places depending on their life experience, their personality and the type of dementia they are experiencing. Supporting people with dementia and those that care for them requires a focus on a range of relationships. In my first book Caring for Older People: A Shared Approach, I outlined three approaches to care based on my research that focused on relationships between older people, staff and families: individualised, person-centred and relationship-centred (Brown Wilson, 2012). I use the term relationship-based approaches to describe an approach that requires the development of positive relationships with the person, their family and other staff members. In my early research, I observed the same staff adopting three different approaches, individualised, person-centred and relationship-centred, for different people at different times. Those observations have been used to develop a continuum of care along which each approach is based. This means that there may be times when we, as professional caregivers, may focus on individualised care but then move to a more person-centred approach when the context enables this. This moves our practice away from the ‘all or nothing’ argument, where staff working in dementia care feel they do not have the time to implement person-centred care. In this chapter we will examine different approaches to care and how they might be implemented. We will discuss individualised, person-centred and relationship-centred care, reviewing the differences, the evidence and application of each approach. The key argument proposed in this chapter is that as we get to know a person, we understand the stories being shared with us about their life experiences, which can then be integrated into the everyday care routines for that person, whether they are in a hospital environment, or live in their own home, assisted living or long-term residential environments. Irrespective of the location, the value of relationships in care provision remains a consistent imperative in ensuring the quality of effective and meaningful care for people with dementia. Retaining this emotional connection becomes vital to the person with dementia as their ability to communicate alters.

What do we mean by a continuum of care?

As nurses and healthcare practitioners, we may adopt a model of care that the organisation in which we work dictates. At the same time, we ourselves have a worldview of what it means to provide care or to be a ‘professional caregiver’. If the two approaches do not reflect each other, there can often be tension that affects our overall job satisfaction. Students who seek to implement theoretical models of care often report a tension between what they are learning and the pressures exerted by the environment that constrains how they practise. This means many students and early career practitioners become encultured into the way the organisation wishes to deliver care, without examining other ways of working. The concept of a continuum of care provides you with the flexibility of being able to meet the competing demands of a busy environment whilst practising with a focus on relationships when supporting people living with dementia. I have adopted the concept of a continuum to describe a range from individualised developing to person-centred and on to relationship-centred care. There are gradual changes that might occur in your practice that enable you to progress from an individualised approach to person-centred care and then on to relationship-centred care – and this may be context specific and therefore different for everyone. Equally, there might be times when you need to return to an individualised focus and this is also acceptable as it means that you can return to adopting person-centred care when the context enables you to do so. Before we can understand how the continuum works, we need to consider what each approach means and how we implement relationship-based approaches in everyday practice.

Individualised care

Individualised care was initially considered as an antidote to task-centred care, where the focus was primarily on meeting the needs of the organisation and meant that the needs of older people or those with dementia were seen as secondary to the needs of the organisation. There has been a cultural shift over the past two decades with a greater focus on addressing the needs of the person with dementia.

Activity 2.1 Critical thinking

Explain how you might implement individualised care in an organisation where you are currently practising:

- Write down how you provide choices for the people you are caring for.

- What are these choices related to?

- How do you know about these choices?

- Are these choices unique to this person; if so how?

- What are the areas that are common to many people?

- How does this influence the management of your care?

- Are there any choices you are unable to accommodate – why is this?

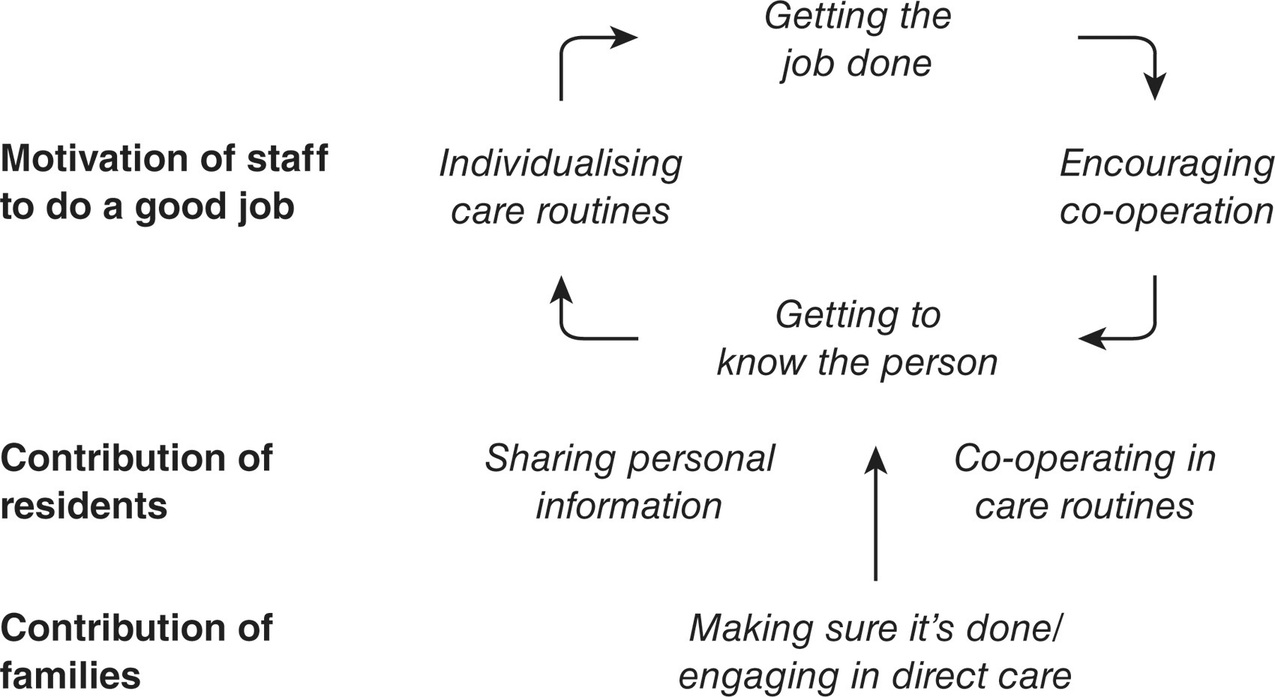

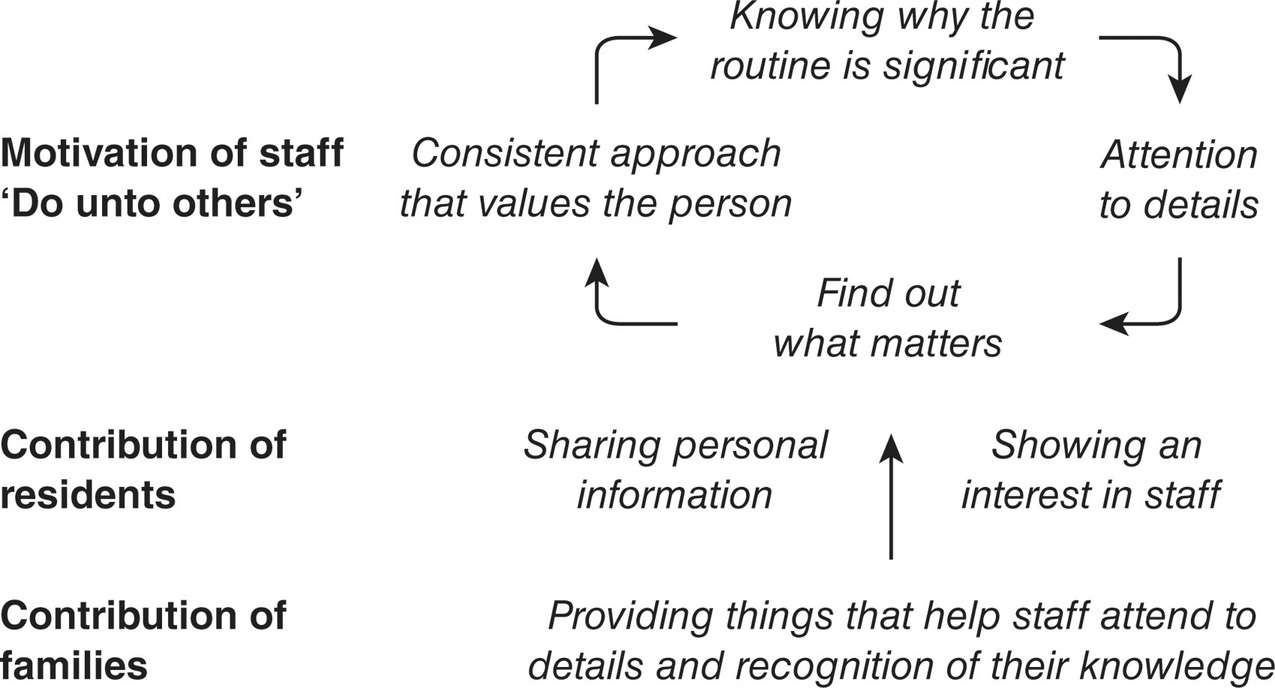

There have been some concerns raised that people implementing individualised care confuse this with person-centred care in dementia environments (Brooker and Latham, 2015). A helpful distinction might be to consider the focus of individualised care as remaining focused on the task. Returning to Activity 2.1, consider if all of the choices are related to a task of care that needs to be delivered for that person. Whilst adopting an individualised approach takes into consideration an individual’s likes/dislikes and choices, they remain focused on how we as practitioners can deliver safe and effective care that meets the identified needs of the individual. This is not poor care but was described in my research study (Brown Wilson, 2007) as the minimum standard of care that older people and families wish to receive. For example, where I observed an individualised approach to care, staff were highly motivated to do a good job and often defined this in terms of the task of care and how they were able to achieve this whilst still promoting the choices of the individual (Figure 2.1). However, we also know that choice is often provided within the confines of what the organisation is prepared to deliver and the level of deviation from the accepted norm that the organisation is prepared to permit. Returning to Activity 2.1, consider when you have not been able to deliver on the choices of an individual – why is this? When you are not able to deliver on the choices of an individual this is generally due to competing needs of the organisation. However, when we do not deliver individualised care, we could say we are falling below the minimum standard that older people and families view as acceptable care. Certainly in my research, there were times when individualised care was necessary such as when new staff were starting and didn’t know the people they were supporting or when a person was initially admitted to the environment in which staff are working. In this context, we can view individualised care as a starting point on a continuum of care where the focus is on ensuring good quality care and using care routines as an opportunity to get to know the person.

One of the concerns staff and students have shared with me over the years has been that they often feel unable to deliver person-centred care all of the time and so they tend to revert to a focus on the task with the belief that they don’t have time to implement person-centred care. However, I have seen staff adopt different approaches to care at different times of the day depending on whom they are working with and who they are supporting. In this context, the staff move between individualised and person-centred care working within the constraints of the organisation. However, many staff may still find themselves working alongside staff with different values and motivations and so may need to adopt a level of flexibility in how care is delivered as part of an overall team. Staff who described their motivation as being able to deliver good care also listened to the stories shared by residents and their families that enabled them to provide individualised care. Therefore, individualised care could be conceptualised as a starting point on a continuum, to ensure the focus remains on good quality care alongside using care routines to get to know the person (Brown Wilson and Davies, 2009).

Practice Scenario 2.1

Beatrice had been an English teacher and had won prizes for her grasp of language and spelling in particular. Her husband Rodger recounted the first holiday when he realised something was wrong when his wife started asking him how to spell words for the postcards she was writing. When he looked at the postcards, the words did not make any sense. At this point, they began to make plans for the future. When I met her, Beatrice had advanced dementia and was unable to communicate verbally. There were times when Beatrice would whisper to staff but the words did not appear to make any sense and then the staff were unable to understand her, so Beatrice would go quiet. There was a consensus by the staff that Beatrice did not understand what was happening. Beatrice often exhibited a range of agitated and repetitive behaviours that meant she was always changing seats and sitting down on people already in a seat. She would walk in quick bursts out of the lounge room but would not appear to know where she was going once she had left. She would often turn off the light when she left the lounge room engendering shouts from other residents and staff still in that room. Staff told me Beatrice had been a teacher and they were able to recount what Beatrice liked to eat, how she liked to dress and how she preferred her hygiene needs to be met. Her husband Rodger would visit every 2–3 days in the afternoon. Just before Rodger’s visit, Beatrice would become very agitated but on his arrival Beatrice would sit or walk with him and could often be seen to move to sit on his lap. After the visit, Beatrice would routinely sit quietly for up to an hour in the lounge room. On one afternoon, I noticed Beatrice had been physically restrained to a chair by a small table. I asked why this was the case as it was about the same time Rodger would usually visit. Staff informed me that Rodger was not visiting this afternoon and Beatrice had become so agitated that the staff had feared for her safety. They had undertaken a risk assessment for physical restraint and considered this was the best option. Rodger had told me that he and Beatrice would often walk in a local country park and watch the ducks, which was an activity they had shared for many years. Beatrice had loved the outdoors and had been an avid gardener.

Source: from Brown Wilson (2007), unpublished data.

Staff caring for Beatrice were highly motivated to ‘do a good job’ and they often defined good quality care as meeting the needs of people in ways that reflected their likes, dislikes and choices they might have made prior to moving into the care home. Staff could identify Beatrice’s likes and dislikes about the food and her dress and how they responded to these preferences. For example, one staff member explained that Beatrice’s annoying habit of turning the light off every time she left the lounge room could be explained by the fact she had been a teacher and would have always been the last person out of the room and so would always have turned off the light. Understanding the significance of Beatrice’s action I believe was the first step in moving towards person-centred care as this staff member understood the significance of the action for Beatrice. The key difference here was the recognition that this was more than a random behaviour but had significance in relation to Beatrice’s life history. Since Beatrice was unable to verbally share this information, staff relied on the family contribution of sharing stories about Beatrice’s life. Without the contribution of families, staff would not be able to individualise dementia care in the same way.

Recognition of a significant behaviour is a necessary first step in person-centred care but by itself is not sufficient to change the focus of care. This information now needs to be applied in ways that promote the identity of the person, developing insight into details that are significant to the person with dementia.

Person-Centred Care

Person-centred care is becoming increasingly synonymous with good quality care. Person-centred dementia care is based on the philosophy of Professor Tom Kitwood, whose pioneering work articulates how personhood is conferred to a person with dementia by the social responses and environment in which the person is located:

a standing or status that is bestowed on one human being, by others, in the context of relationship and social being. It implies recognition, respect and trust. (Kitwood, 1997: 8)

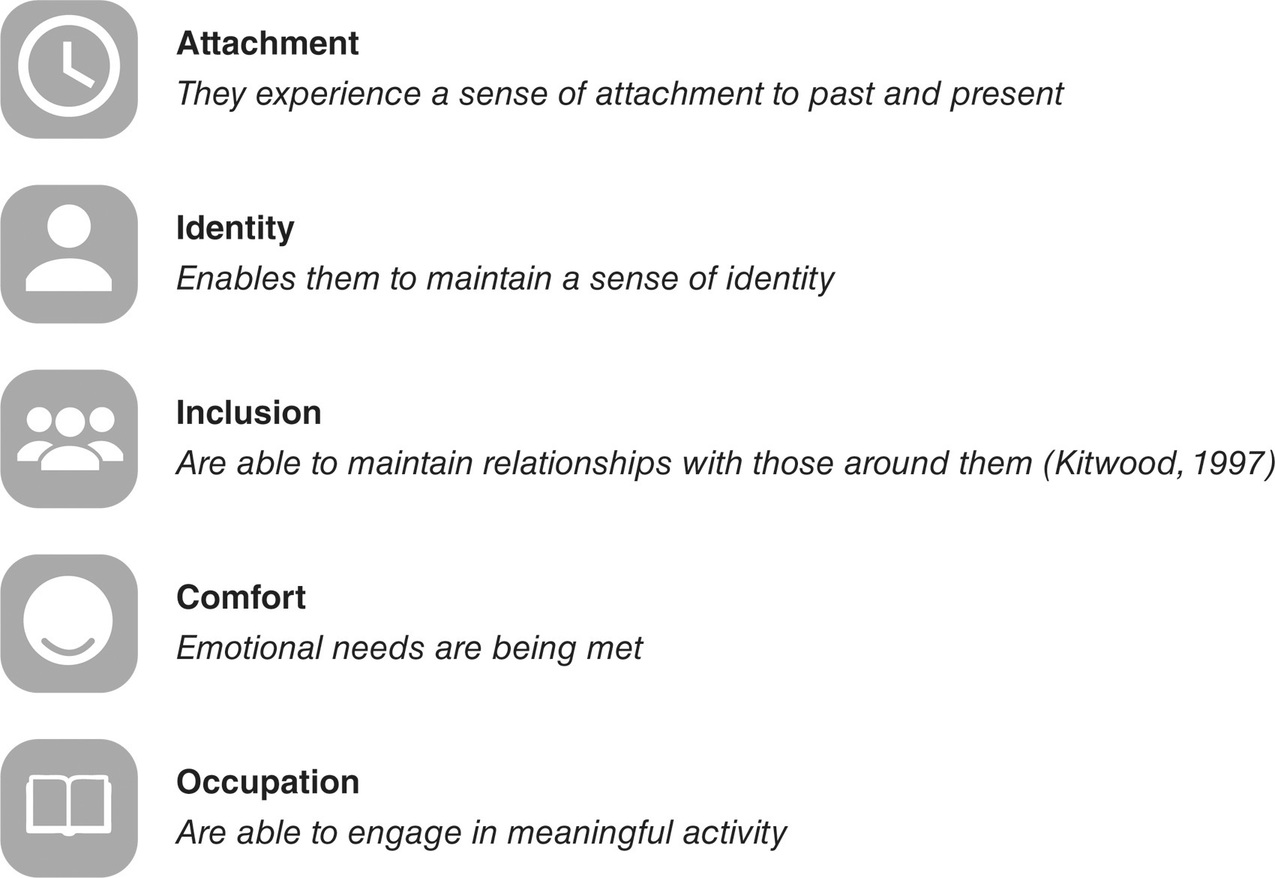

‘Dementia reconsidered’ (Kitwood, 1997) challenged the medical model and prevailing culture of dementia care by considering the viewpoint of the person with dementia. Professor Tom Kitwood identified that people with dementia have five overlapping needs which will be influenced by the environment in which they are cared for and the relationship with those who care for them (see Figure 2.2). Kitwood suggested a way forward for dementia care that proposed to make staff aware of how their actions worked against the wellbeing of people with dementia often unintentionally. He based this work on the idea of a ‘malignant social psychology’ that often robbed people with dementia of their self-esteem, confidence and eventually their personhood (Kitwood, 1997).

Figure 2.2 Five needs of a person living with dementia, based on Kitwood (2007)

The person with dementia is more likely to experience a greater sense of wellbeing when each of these domains are considered in their care (Figure 2.2).

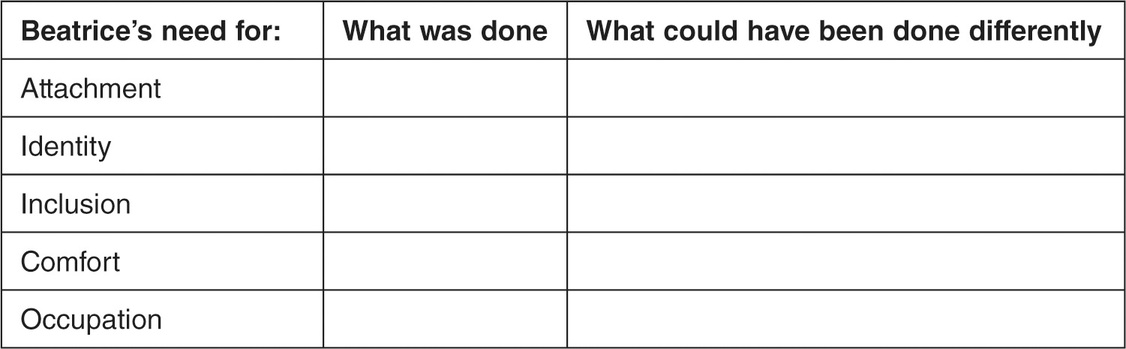

Activity 2.2 Critical Thinking

Using Practice scenario 2.1, identify how Beatrice’s needs might have been met using Kitwood’s principles in Figure 2.2.

Using Kitwood’s principles above, you would have interpreted Beatrice’s behaviour as communicating an emotional need. For example, when Beatrice was trying to sit on other residents’ laps, you might have considered this as missing her husband, so you might have suggested you could sit and hold Beatrice’s hand, so she felt an emotional attachment at that point in time. When Beatrice was engaged in repetitive behaviours, rather than restraining, a member of staff might have walked with Beatrice in the garden to engage in meaningful activity that she has enjoyed in the past, so maintaining her sense of identity. These ideas suggest a very different approach to Beatrice’s actual experience of care.

Dementia Care Mapping (DCM) was developed as a way of assessing the wellbeing of the person with dementia and the interaction they had with their environment and others using a coded observational schedule. DCM can be used both as a tool and a process (Brooker and Surr, 2006) and consists of in-depth observations of a person with dementia with their responses of wellbeing or ill-being coded at intervals (BSI, 2010). Observers are trained to code signs of wellbeing or ill-being demonstrated by the person with dementia into time frames that provide an overall impression of how long a person may experience either wellbeing or ill-being. In addition to this, actions from care workers are also recorded. Actions that fall into the categories of malignant social psychology are described as personal detractors and could include ignoring a person when they are trying to attract attention. Actions that support the wellbeing of people with dementia are described as personal enhancers and could include validating the experience of the person with dementia. As a process, feedback to staff occurs following the observation with suggested actions agreed and a follow-up observation undertaken (Chenoweth et al., 2009). Examples of these actions are included in the feedback as ways that caregivers are dealing well with certain situations or issues that may need to be improved, which in turn enhance the experience of both the person with dementia and those caring for them (Rokstad et al., 2013). Kitwood’s approach has been considered important for relocating the person with dementia as central to dementia care.

The legacy of Tom Kitwood remains central to the provision of person-centred dementia care as more organisations are now considering how to implement person-centred care as a mechanism to improve the quality of care. A reflection of this progress is that policy documents now refer to person-centred care (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2007). One criticism in the literature has been a lack of detail in how people might implement person-centred care (Dewing, 2004). Dawn Brooker (2004) has subsequently developed Kitwood’s theory of person-centred care into four key principles for practice, the VIPS Framework, being: V = Values and promotes the rights of the person; I = provides individualised care according to needs; P = understands care from the Perspective of the person with dementia; S = supportive Social psychology and social environment that enables the person to remain in relationship to others. An expert consensus group has identified a range of indicators grouped around the domains of VIPS enabling organisations to assess how they achieve each domain (Brooker and Latham, 2015). For example, a day care service used this model to evaluate its service demonstrating an achievement of above good quality in every indicator and excellence in 83% of the indicators (Association for Dementia Studies (ADS), 2010) with the conclusion that:

The service is an exemplar of positive person-centred dementia care. The staff team are passionately committed to ensuring that all the people with dementia who attend the centre have a high quality service, which meets their individual needs, promotes their abilities and enhances their wellbeing. (ADS, 2010: 9)

The VIPS Framework has been used in a range of projects to support services in achieving person-centred care alongside the development of training materials (Brooker and Latham, 2015). An early example was in the Enriched Opportunities Programme (EOP) which used these principles in extra care housing and care homes. This approach was a multi-level intervention that focused on an activities-based approach to care (Brooker and Woolley, 2007). Each of the development sites identified a senior person, known as an EOP Locksmith, who was responsible for identifying residents’ needs and developing a strategy for person-centred care as well as being responsible for changing practice to ensure the implementation of person-centred care (Brooker and Woolley, 2007). Direct care staff were also engaged to be more involved in the fun activities, which encouraged them to see the ability of the person with dementia (Brooker and Woolley, 2007). Overall, this programme demonstrated statistically significant improvements in wellbeing and depression scores alongside an increase in diversity of activity for many residents. It is important to note that these study sites were already nursing homes providing good quality care and were interested in being part of the research (Brooker et al., 2007). However, this study demonstrates that it is possible to provide person-centred care in an organisation and subsequently improve outcomes for people living with dementia.

Person-centred care may mean different things in different environments, so it is important to consider how person-centred care is implemented and how this might transfer to improved outcomes for the person with dementia. The VIPS Practice Model (VPM) was developed to support the implementation of person-centred care in residential aged care facilities in Norway to support staff to focus on the interactions between staff, the person with dementia and the environment (Rosvik et al., 2013). VPM includes a clear structure:

- A weekly consensus meeting (45 minutes–1 hour) with a set structure and set roles and functions in the team.

- Staff training underpinned with a manual with practical knowledge and examples of PCC, non-pharmacological treatment related to each indicator in the VIPS framework and assessment tools.

- Supportive management that formed a PCC expertise group common for the whole institution consisting of four experienced senior staff to be available to support the staff on request (Rosvik et al., 2011).

- A Registered Nurse responsible for speaking with the person with dementia and the family to find out about their life history and how this might impact on behaviours and emotions, becoming the coach for other staff and using this knowledge to support a change in care (Rosvik et al., 2013).

Rokstad and colleagues (2013) compared VPM to Dementia Care Mapping and education alone involving 624 people with dementia living in residential environments in Norway. Only 446 people completed the final assessments and there were no statistically significant results for behaviours or quality of life although there were promising results for depression (Rokstad et al., 2013).

Lyn Chenoweth and colleagues in Australia have also developed a person-centred model based on Tom Kitwood’s principles (Chenoweth et al., 2009, 2014). Caring for Aged Dementia Care Resident Study (CADRES) compared person-centred care (PCC) to DCM and usual care. Staff were observed to be implementing PCC (Chenoweth et al., 2009) in the following ways:

- Attending to the person’s feelings, experiences and perceptions of that person’s own reality.

- Attending to the person’s emotional, social, physical and spiritual needs and establishing positive relationships.

- Assisting and encouraging the person to maintain function and engage in meaningful life experiences.

- Creating an enriched environment.

- Avoiding triggers for distress.

An interesting observation from this study was that few care plans in the study described the care delivered (Chenoweth et al., 2009). This raises an interesting point in how staff may implement PCC but find it difficult to document how this is achieved. These interventions significantly reduced agitation in both the PCC and DCM groups (Chenoweth et al., 2009) although there were no statistically significant outcomes for staff burnout or health (Jeon et al., 2012). The costs were calculated taking into account staff time in dealing with agitation and demonstrated a cost saving per resident for the behaviours averted through person-centred care (Chenoweth et al., 2009). Further work by this team in the PerCen study (Chenoweth et al., 2014) demonstrated a statistically significant difference in both agitation and quality of life for people living with dementia with 59% of staff implementing PCC.

The studies reviewed so far demonstrate the difficulty in identifying measurable outcomes that can be influenced by positive relationships and wellbeing experienced by the person with dementia. Lyn Chenoweth and colleagues used large randomised controlled trials to demonstrate a reduction in need-driven dementia-compromised agitation and the associated costs in staff time when individually tailored solutions were developed (Chenoweth et al., 2009, 2014). This provides us with a promising direction in how we might not only implement relationship based approaches to care but also identify the benefits these approaches bring to the person with dementia and staff.

The research I conducted in residential environments in the UK adopted an inductive qualitative approach where I observed how different staff enacted the care routines and interacted with older people, including those with dementia, families and other staff (Brown Wilson, 2007). Using observation and interviews with residents, families and staff across three residential aged care facilities I was able to identify how staff enacted person-centred care (see Figure 2.3). Staff shared why they adopted different practices and what motivated their care which contributed to the detailed nature of the care interactions that enabled positive relationships leading to person-centred care and relationship-centred care (Brown Wilson and Davies, 2009; Brown Wilson et al., 2009).

Figure 2.3 Person-centred care

If we return to the idea of a continuum of care, moving from individualised to person-centred care we are moving from knowing what routines to implement to understanding why these routines hold significance for that person and consequently making a decision to implement the details that matter to the person with dementia. Staff who enacted person-centred care in this way described a motivation to deliver the care they knew the person wanted because they would like someone to do that for them when they were in that position (Brown Wilson, 2009). When I observed person-centred care in action, the contribution of families was evident in helping out with little things that took up staff time, such as tidying up clothes so they were easier to find, or helping with the afternoon tea trolley. Older people themselves would also share stories that were imbued with symbolism or recount important life events. When a person with dementia was unable to continue sharing stories, families would take on this role.

Practice Scenario 2.2

One evening I was spending time with staff and a family member when her father, who was a retired cattle farmer with dementia suddenly announced he had to ‘get the cows in and shut the gate’. The daughter explained how she had told the staff about her father’s past routine so they understood this behaviour. The staff member said she knew this background information and subsequently the routine in the care home was to explain the cows were already in and offer the gentleman a cup of tea as this was what would have happened after he had ‘closed the gate’. This approach recognised that being a farmer was still an important aspect of this person’s identity and rather than remind him he was in a care home, the staff would seek to maintain that identity by continuing the same routine he was used to in his own home.

We can see from Practice scenario 2.2 that families play an important role in contributing important information and supporting staff to understand the significance of behaviours when connected to previous routines. Not all people living with dementia have families. Staff in one dementia facility I was supporting described how they had looked at photos displayed in one resident’s room to see how she had dressed before she had dementia. In every photo there had been jewellery and the staff made the effort to ensure each day that this resident was wearing her jewellery as this had been an important part of this woman’s identity. These staff also recounted how not everyone attended to this important detail and that it can be dependent upon the person who is delivering care. Person-centred care demonstrates a consistent approach that values the person, which needs to be applied across shifts and teams and we will be exploring what this means in later chapters.

We saw earlier that meaningful activity is also an important element of person-centred care and this aspect can sometimes be lost in the care routines. Knowing that people liked gardening or enjoyed doing housework are all important ways of supporting people with dementia in maintaining meaningful activity. In one home I visited, a staff cleaner told me that one of the women would always come up and ask if she could help her in her cleaning and she would be given a cloth to help. We discovered that this lady had been a professional cleaner before she had developed dementia. Knowing this enabled the staff cleaner to engage the resident in conversation during the time the resident was helping her.

Person-centred care focuses on the person and what is important to the person, taking into account the contribution of the families and staff (Figure 2.3). Within residential environments there are often competing demands where staff tell me that it is difficult to routinely implement person-centred care. In considering the approaches I have outlined, person-centred care can be an extension of the care routines and when embedded within them, can promote a sense of wellbeing for the person with dementia. In my research (Brown Wilson and Davies, 2009), I observed teams of staff that worked in a way that enabled them to balance these competing demands and address the needs of staff and families. This was described as relationship-centred care.

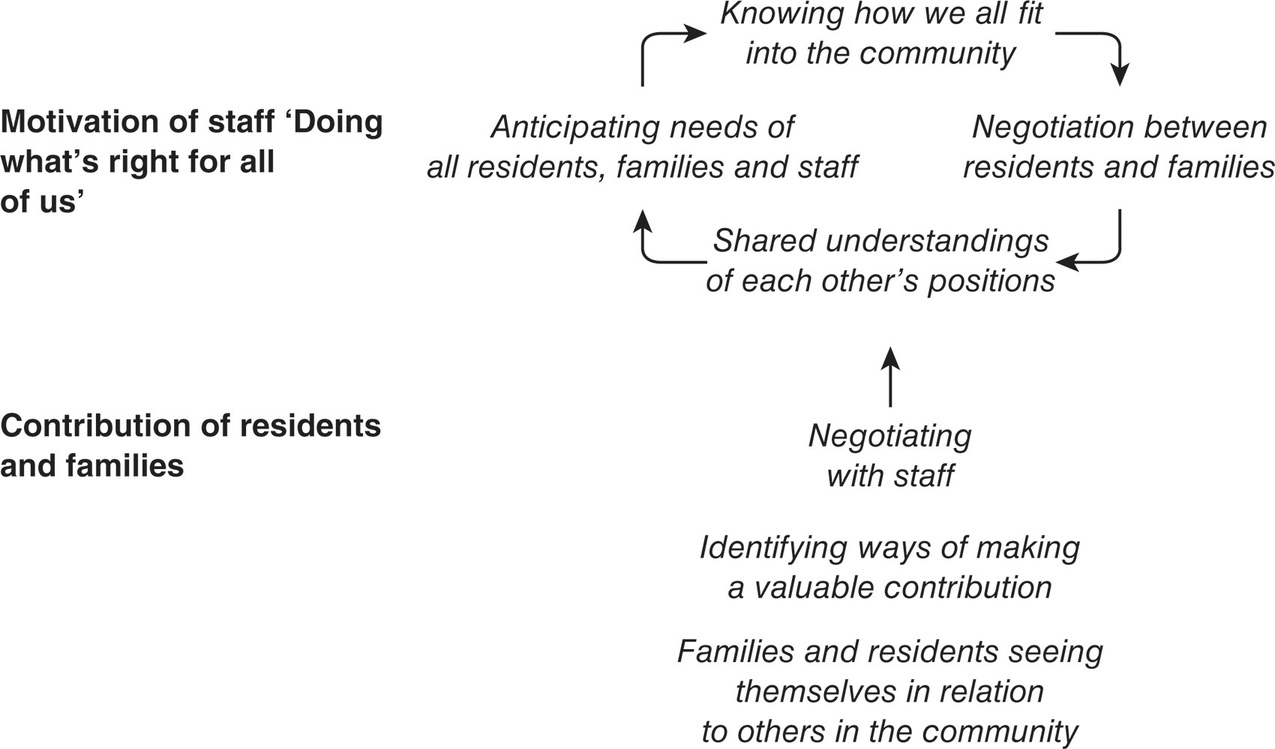

Relationship-Centred Care

Relationship-centred care is the third approach I observed that moved from a focus on the person to a focus on relationships, considering the needs of all stakeholders in the relationship. This approach understood that there would be times when both family caregivers and staff would also have needs that might need to be considered within the relationship. Relationship-centred care (see Figure 2.4) is the final approach along the continuum of care we discussed at the beginning of this chapter.

Relationships in healthcare practice have been described as central to the therapeutic encounter (Tresolini et al., 1994). This concept challenges a purely biological approach to healthcare through consideration of the significance of the relationships between practitioners and those they care for as well as the communities within which they practise (Tresolini et al., 1994). Relationship-centred care is based on a therapeutic relationship which should have as its foundation a shared understanding of what health and illness means to the person and those close to them, in the context of the community in which they live. Relationship-centred care goes beyond the holistic person-centred model to consider relationships between other practitioners as well as between the person and their community:

Figure 2.4 Relationship-centred care

Practitioners’ relationships with their patients, their communities and other practitioners are central to health care and are a vehicle for putting into action a new paradigm of health that integrates caring, healing and community. These relationships form the context within which people are helped to maintain their functioning and grow in the face of changes within themselves and their environment. (Tresolini et al., 1994: 24)

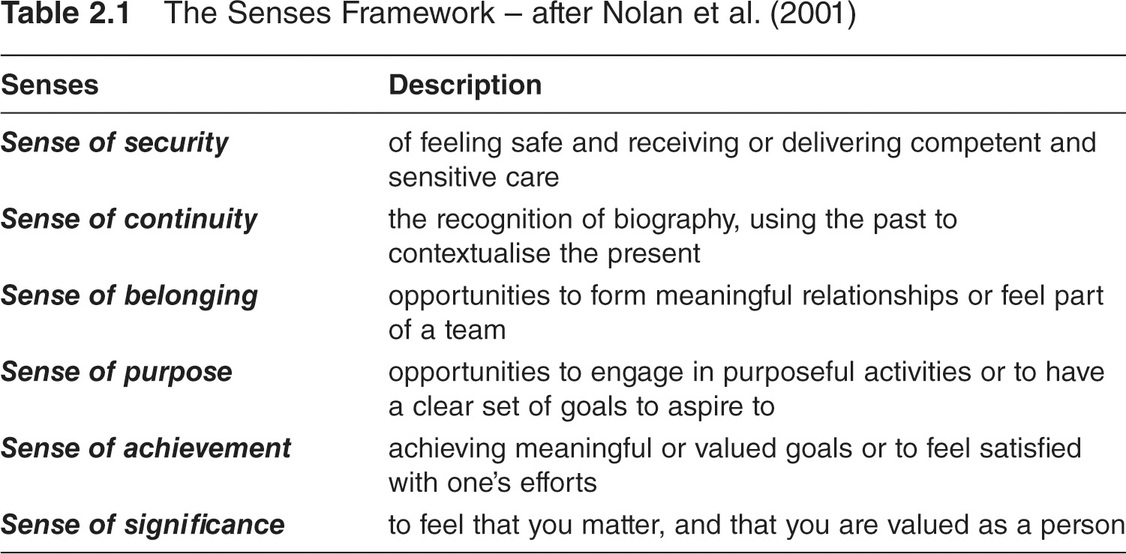

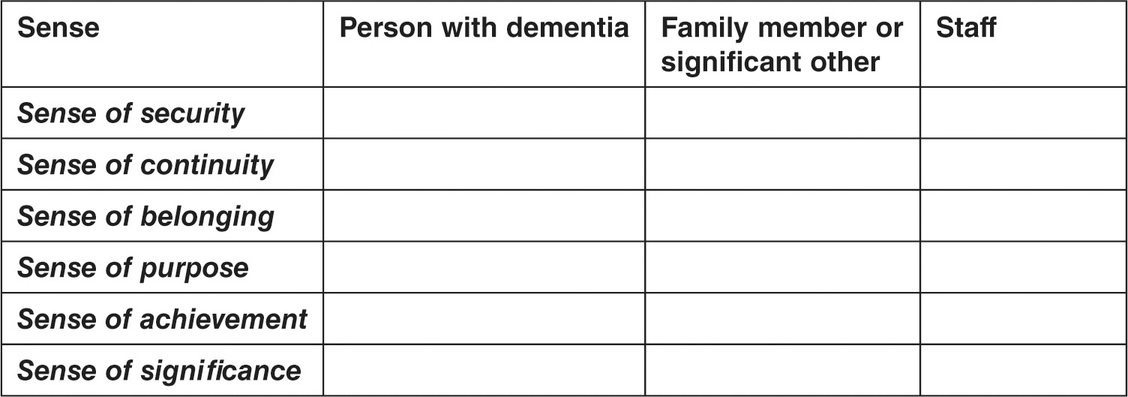

Using the principles of relationship-centred care, Professor Mike Nolan and his team (Nolan et al., 2001) developed the Senses Framework in response to a lack of a clear therapeutic direction for the care of older people (Table 2.1).

The term ‘Senses’ was chosen to reflect the subjective and perceptual nature of what determines ‘good care’ for both older people and staff, supporting the development of therapeutic relationships. The subjective nature of the ‘Senses’ would suggest that different contexts and interventions could create the ‘Senses’ for people in different ways (Nolan et al., 2004). It is proposed that when staff, older people, and their families experience the ‘Senses’ an enriched environment for care is created where positive relationships may develop (Nolan et al., 2006a). Ryan et al. (2008) described how staff demonstrated that the ‘Senses’ also provide a mechanism for how good relationships develop within dementia care triads in an organisation delivering community-based respite care. On the one hand, staff would look at the biography of a person with dementia and then identify an activity they might enjoy. The caregivers however were always informed about the activity and asked their opinion. This promoted a sense of continuity for both the person with dementia and their carer whilst promoting a sense of achievement for the staff that they were doing something meaningful and so making a difference. In this way, Mike Nolan and his team argue that relationship-centred care attends to the needs of everyone in the relationship (Ryan et al., 2008). Nolan et al. (2004) argue that respect for personhood underpins positive relationships and Clare Surr (2006) concluded that relationships with staff, other residents and families were able to both promote or undermine the sense of self for a person with dementia (Surr, 2006).

The complexity of a relationship and understanding the needs of everyone in the relationship is challenging. In the observations and interviews referred to in the previous section (Brown Wilson, 2007) I observed how staff used the biographical knowledge from person-centred care to anticipate the needs of the person and then engage in negotiation to ensure the needs of everyone in the relationship (residents, families and staff) were met. This resulted in shared understandings and a sense of community (Figure 2.4). Practice scenario 2.3 provides an example where all of these relationships were taken into account to improve the experience of all residents, staff and the family member.

Practice Scenario 2.3

Mr Au was an older man who would often move around the ward area, going up to people and trying to touch them. Other people and staff became very agitated with him and would try to make him stop, which resulted in aggressive behaviour both from Mr Au and other people towards Mr Au. The family of Mr Au never visited and staff drew the conclusion that he wasn’t cared about. In workshops I was conducting with staff, I suggested that contacting the family might help explain this behaviour. The staff contacted his daughter to discuss Mr Au’s behaviour. She told the staff her father used to volunteer in a Buddhist temple and would walk around the temple blessing people and she thought her father was following this routine. The staff then told the other residents in the ward that Mr Au was blessing them and all the other residents accepted this gesture. The staff began to accept this behaviour and Mr Au no longer displayed aggression. Initiating this dialogue with Mr Au’s daughter enabled the daughter to build a relationship of trust with the staff as they began to contact her more regularly. Mr Au’s daughter then disclosed that her father had attacked her with a knife before he was admitted to the ward and she was very frightened of him, which is why she did not visit. The staff then worked with Mr Au’s daughter to enable her to understand the dementia and provided a supportive environment where she felt safe to visit her father.

If we consider relationship-centred care using Figure 2.4, we can see that once the staff recognised the significance of the routine for Mr. Au, they were able to anticipate that this activity would upset other people on the ward. Staff then explained the context of Mr. Au’s behaviour to other residents, contributing to shared understandings. Staff now recognised how Mr. Au was contributing to the community within the ward. Staff also recognised that they also needed to focus on the needs of the daughter to enable her to contribute to her father’s care.

Activity 2.3 Critical thinking

Using Table 2.1 identify how each of the senses were being created for Mr Au, his daughter and staff.

Relationships within health and social care environments are generally developed through care and daily living routines for which people may need support (Brown Wilson and Davies, 2009). As we have seen throughout this chapter, routines can be the vehicle by which staff are able to develop knowledge about a person’s biography; this is the first step in being able to identify meaningful activity that is relevant to different people. Being able to engage in meaningful activity is a key part of feeling a sense of belonging and a sense of purpose (Nolan et al., 2006a). A person with dementia who sees their role in the care home as ‘working’ or ‘helping staff’ is able to maintain their sense of self when the role is recognised and valued by others (Surr, 2006). I propose that recognising meaningful activity promotes a sense of community where everyone’s contributions are valued (Brown Wilson, 2009). Meaningful activity in helping out in the life of the home is becoming more common for those who wish to maintain roles they may have had in their own home and contributes to an overall sense of community (Owen, 2006). People with dementia can make a contribution to the community in different ways and understanding the biography of a person with dementia supports staff in enabling that person to maintain an important role, as Practice scenario 2.4 indicates.

Practice Scenario 2.4

Staff would bring the laundry up to the lounge room each afternoon to fold and Heather would tell the other women that she had to help the staff now and move across to take her place at the table. She would talk to the staff while she was helping fold the laundry. She was often animated and spoke to the staff about her experiences as a younger woman. One day I noticed Heather wasn’t participating and asked the staff why this might be and was told that Heather was feeling tired. Heather had told the staff she needed a ‘day off’. Staff told me that this was an activity that Heather initiated on most days because she took pride in being able to do housework as this had been her role all of her married life. Heather told me that she was helping staff and this was her job. She spoke with a sense of pride when speaking about this.

Source: Brown Wilson (2007).

Families also have important contributions to make to the community of the residential environment. This can range from having conversations with other residents who might not have visitors, helping staff by organising clothes or being involved in meals or afternoon tea rounds. Engaging in different activities brings families into contact with staff and so relationships are able to be developed. Families who engaged in these actions would demonstrate to me they had developed a shared understanding of what was happening in the home. For example, one son told me how he understood there were times when staff were busy, which meant his dad might have to wait for non-essential care. However, he also told me that when his dad did need care, staff would always provide this immediately. This understanding enabled negotiation between families and staff when views about what was needed for the resident differed. For families to reach this point, staff had to engage in person-centred care by demonstrating consistent attention to important details of care.

A person with dementia may not be able to engage in negotiation verbally when they need something different but changes in their behaviour may well be an indication that a change to the usual routine is needed at this point. Understanding this and acknowledging the feelings being communicated may well be part of the negotiation process as the staff or family member considers the impact this might have on the routines for the day ahead. Anticipating the difficulties this pressure might create for different people and attempting to consider the way in which the routines might be enacted in a different way may help satisify the needs of everyone in the relationship.

Conclusion

Returning to the concept of a continuum of care, we have seen that when viewed together individualised, person-centred and relationship-centred care can be viewed as a continuum where the everyday routines provide a vehicle to develop a greater understanding of the person with dementia, their family or significant other and staff. This might be best described as a cycle of care (see Figure 2.5).

Residents and families consider individualised care to be the minimum standard where choice is offered and likes and dislikes are recognised and acted upon. This could be considered a precursor for person-centred care, as the routines become a vehicle by which staff get to know the person with dementia and their family. This could be described as knowing ‘what’ is needed in the care routines. Sharing stories leads to an increased biographical knowledge that enables staff to understand why different routines are significant and how they underpin the personhood of the person with dementia. We might describe this as the ‘why’ of care as we understand the significance of the routines from the perspective of the person with dementia. Relationship-centred care maintains the importance of the personhood of the person with dementia (Nolan et al., 2004) but also means that the needs of families and staff can also be recognised alongside the needs of that person (Ryan et al., 2008). We could describe this as the ‘how’ of care as we recognise and value that everyone in the care relationship has a contribution to make, anticipate needs, develop shared understandings and be prepared to negotiate to ensure everyone’s needs are met. To achieve this, a culture of community is required that enables shared understandings and negotiation (Brown Wilson and Davies, 2009; Brown Wilson, 2009). This is of particular relevance in communal environments where person-centred care is being enacted in a group context.

There is still limited empirical work on relationship-based approaches to care. This may be due to the difficulty in identifying relevant outcomes that are directly influenced by the process of care. This has been addressed to some degree in person-centred care as demonstrated by the good quality evidence reviewed in this chapter where we saw that agitation was directly influenced by person-centred approaches (Chenoweth et al., 2009, 2014). It was interesting to note that not all outcomes reached statistical significance and this may be due to other influences on the outcomes measured beyond the immediate impact of the care being delivered by staff. These may be issues beyond the control of staff in the wider organisation. In the next chapter, we will explore how the wider context of an organisation might impact on how relationship-based approaches to care might be implemented.

Final reflection

As people with dementia continue their journey, they will come into contact with services at times when they are less able to communicate what is important to them. Our key responsibility as professionals in this field is to consider how to develop therapeutic relationships with the person with dementia, their families and significant others as well as the staff we work with. It is very easy to simply stay at the individualised care end of the continuum and believe we are implementing person-centred care. Unless we understand the importance of biography and what this means for the person with dementia, we will not be delivering person-centred care. We will revisit the key principles from this chapter as we journey through this book.

Further reading

Books

Brooker, D. and Latham, I. (2015) Person-Centred Dementia Care: Making Services Better with the VIPS Framework (second edition). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Brown Wilson, C. (2013) Caring for Older People: A Shared Approach. London: Sage Publications.

Websites

Christine Bryden is a dementia survivor and advocate. This website provides an insight into Christine’s journey and experience: www.christinebryden.com/ (accessed 26/01/17).

The VIPS website has resources to support organisations in implementing the VIPS model: www.carefitforvips.co.uk (accessed 26/01/17).