A Crossing of

the Ways

If we had stopped to ask one of the peasant children tending the striped piglets in that kitchen garden in Bronze Age Denmark, “Where is Elfland?” then she might have pointed to the southeast, adding a little wave of her hand to indicate how impossibly far away it was. Southeast was the direction from which the longboats came with their cargoes of gold, tin, copper, and, sometimes, beautiful foreign brides. Where else could such things have come from but Elfland? Or, the girl might have pointed to one of the nearby mounds. Not the one still under construction for a recently dead chieftain, but a cairn where the bones of one of the early farmers lay and to which the girl’s own family periodically offered sacrifice. Then again, she may have scrubbed the air in a circular motion to indicate that Elfland is all around us.

Let’s follow her first set of directions. Bronze was so important to southern Scandinavia and northern Germany in the years 1800 to 500 BC that the period was given its own region-specific name: the Nordic Bronze Age. Danish archaeologist P. V. Glob described the people who lived in that place at that time as “a people rich in gold” 18 and identified the hundred years around 1250 BC as a brief golden age. But none of the resources that came to define it were to be found in Scandinavia; gold and the tin and copper that make bronze all had to be fetched from afar.

Some of our mound people enjoyed kinship ties with the more advanced peoples of Central and Eastern Europe. Others were bound by economic ties. The ancient Danes acquired the tin, copper, and gold they needed and wanted by dispatching their own amber, seal oil, furs, livestock, pine resin, and probably slaves to the Central and Southern European markets. The kings and queens of Old Elfland probably stayed at home to defend their borders and warm themselves at their open hearths, for they could afford to crew and outfit the ships to go on their behalf. Then, when the raw materials arrived, they set the local smiths to working them into swords, axes, daggers, razors, cult objects, and glittering personal ornaments. Meanwhile, the members of the upper classes who would receive these finished products occupied themselves with patrolling their territories, bankrolling festivals and funerals, and riding out on forays into the neighboring little kingdoms.

The shipmasters, like the smiths, were further down the social scale than the princes whose cargoes they carried. But they seem to be the ones who made the most lasting impression on the later peoples of northern Europe and even us today. The element “dan,” also “don” and “dn,” appears in several European river names and comes from a Proto-Indo-European root meaning “to flow.” The same element occurs in the names of a few peoples of ancient Europe, both on this and the other side of the veil. Denmark in Danish is “Danmark.” Some would have the name refer to an at least semi-mythological King Dan who, ironically, was Swedish, while others point to an equally misty people known as the Dani. Or, “Dan” might simply mean “lowland.”

I prefer door number two. The Dani, if they existed, would have been a river people—not a people who lingered on the banks but who plied the waters in their long, oared boats, stopping only long enough to make a trade before moving on to the next market. The ship19 was central to both the economy and the religion of Old Elfland. Ships were carved on rocks and etched on razors, cast in miniature as cult objects and toted through the fields at festival time. A ship was the means by which the sun returned to the eastern horizon after it had set in the west.

If the Dani originally came from the Mediterranean, where sails had been in use for centuries already, they had discarded them before they arrived on Danish shores. The northern Bronze Age traders kept mostly to the river courses, seldom straying far from land. Though the sail never made it into their hands, the mound people were certainly influenced by the Mediterranean peoples. They had a predilection for outsized spears and double-headed axes, and the graceful figures we see gliding across the faces of Archaic Greek vases have been reproduced more clumsily in the Scandinavian rock carvings. These influences most likely arrived aboard ships.

I’m not suggesting that any Mycenaean shipmaster ever got up in the morning with the intention of sailing to Denmark; I’m sure he never heard of the place. But he may have set sail for Thrace to sell some of his cargo to another trader loading up for a trip upriver where he would touch base with a guy who had connections in the Carpathians. There would have to be some portage along the way, but eventually, the gilded bird’s head prow of a rowboat would nose its way into Old Elfland with news of the wider world.

Where did all these river-faring folk originally come from? As one can see with the Goths, Huns, and Americans, by the time a people has forged for itself a wide-ranging reputation, it is often no longer a single ethnic group but an amalgam of tribes. This was probably also the case with the people we will simply call “Dan.” Keep in mind that they are an “asterisk” people, which is to say that we have no direct evidence they actually existed as such; we can only infer.

Homer used “Danaoi” as another name for the Achaeans or mainland Greeks in his Iliad and Odyssey. The Danaoi were the “tribe of Danaus,” Danaus being a mythical figure who, like Denmark’s King Dan, was probably made up to explain the name of a people whose true origins had been forgotten. Interesting to us is the fact that the Greeks credited Danaus as the world’s first ship builder and that he was said to have fathered fifty daughters, forty-nine of whom murdered their husband on their wedding night in what is, hopefully, an exaggerated memory of the sacred marriage.

Greek is an Indo-European language, so there’s a good chance that the “Dan” in “Danaoi” also means “river.” Around the same time that the Danaoi were fighting it out with the Trojans (1200ish BC), a Danuna people were leaving their homes in Anatolia to join the roving Sea Peoples in the eastern Mediterranean. The Sea Peoples were more or less homeless. After scuffling with the Egyptians, the Danuna may have gone to seek their fortunes among the less organized tribes of Europe.

The medieval Irish literature, which records older mythological traditions, speaks of the Tuatha Dé Danann, a race that dominated Ireland before the Irish themselves had arrived. The Tuatha Dé Danann were skilled in everything from metallurgy to magic. They eventually lost control of the country, but the victorious Irish continued to revere them as gods. At some point, the Tuatha Dé Danann retreated inside the hills and became the fairies of Celtic lore. Their name means “Tribe of the Danu,” Danu being an asterisk goddess. We know nothing about the Irish Danu except her name, but there is a goddess Danu in the Rig Veda, her name deriving from that same ancient root meaning “to flow.”

But the little peasant girl in the farmyard would not have been thinking of any of this when we asked her for directions to Elfland. The barrow, however, would have loomed large in the corner of her eye as she went about her daily business. She would have had a healthy respect for it, if not an actual fear of the draug or living dead who lingered inside it. But more numerous than either the old stone passage graves or the more recent flat-topped mounds were the cup-marked stones that popped up throughout the landscape. These, too, were portals to Elfland.

Cup-marked or bowl stones are found throughout Eurasia, but it’s here in Old Elfland that we find them in their highest concentration. The “cups” in most of these stones were pecked out during the Neolithic and added to over the course of time. In addition to the cup marks, which were made to hold offerings, there are handprints, footprints, and four-spoked wheels representing the sun. Footprints indicated the presence of a deity, as they still do in Hinduism and Buddhism. The worshippers who made offerings at these stones may have believed that humans could not perceive the whole of a god any more than a two-dimensional resident of Edwin Abbott Abbott’s classic novella Flatland could perceive a three-dimensional being.

The arrangement of the “cups” or hollows scattered across these stones appears haphazard. It’s tempting to think the stones might be maps of the night sky, but no constellations have been definitively identified. The stones look lonely nowadays, but thousands of years ago they would have been the focus of bustling activity. The pictographs would have been filled with red ochre; milk, honey, and tallow would have been poured over the stones and flickering lights placed in the hollows—at least, that is how I imagine it. The details are uncertain.

We know that by the historic era the cups held offerings of milk, but in The Chariot of the Sun, Peter Gelling proposes that the cups were originally made for kindling new fires using bow drills and tinder. People didn’t go around kindling fires every day. It was such a hassle, in fact, that the Tybrind Vig people carried around glowing embers inside their canoe, stoking up the fire as needed rather than starting one from scratch. It was always easier to keep an old fire going than to strike a new one. Creating a fire out of nothing was always either a desperate act or a ritual one. The sexual connotation of whirling a wooden rod around inside a hole is hard to miss, so the making of this “spark of life” may have been central to a fertility ritual.

In later periods, it would be mostly women who petitioned the spirits resident inside the stones. They came to ask for the gift of a child or for a loved one to return from a journey. Because the stones were frequented by infertile women, they would also have been good places to leave unwanted babies. Such children, with their strong links to the ancestral spirits, probably enjoyed a privileged upbringing in the village. Perhaps this was the story behind the popular Anglo-Saxon girl’s name Aelfgifu, “elf gift.”

There’s another place where we might we find evidence of the Old Elflanders’ own elves. Those little striped piglets had to be taken into the forest regularly to dine on beech mast and acorns, and when the peasant girl led them in among the trees, she knew she was entering a realm where dwelt another kind of elf: the black elf.

If a prince of Old Elfland wanted to surprise his young son with his first sword, it was not enough to send for the bronze ingots from the south and to engage a smith, for the smith also needed charcoal. Without charcoal, there was no metallurgy: no swords, no daggers, no belt buckles, brooches, or little golden boats. And not everyone knew how to make it. Charcoal burning was a specialized craft carried on deep in the forest by a people who were almost a race apart from those who employed the finished product. The charcoal burners probably only rarely, if ever, met up with a prince face-to-face. They may not even have spoken the same language as he did. Even as late as the nineteenth century, charcoal burners in England and on the continent had their own superstitions and their own vocabulary.

Because no charcoal meant no bronze, these people were indispensable to Bronze Age society. But because they lived most of their lives in the wilderness, minding their kilns deep in the forest and getting very dirty in the process, they were also reviled. Could these masterful but lowly artisans have been the inspiration for medieval Icelandic scholar Snorri Sturluson’s Svartálfar or “black elves,” who lived under the earth and were as swarthy as the “light elves” were dazzling? It’s certainly a thought. The charcoal burners’ own elves—for everyone has their own elves—probably would have resembled the tricksy wood-elves of Mirkwood rather than Tolkien’s gossamer High-elves of the West.

We seem to find elves wherever the paths of two or more disparate peoples cross. But in this day and age, as Tolkien put it, “our paths seldom meet” 20 and “we encounter them only at some chance crossing of the ways.” 21 Short of climbing into a mound, there doesn’t seem to be much chance of meeting up with an elf nowadays. One can go and see the mound people laid out in their glass museum cases, but most of us would like to be able to encounter elves closer to home. Our predicament is not a new one. By the time northern Europe had become literate and the Irish had started committing stories of the Tuatha Dé Danann to parchment, elves had become much thinner on the ground. But perhaps it has always been so. Perhaps the elves are always just out of reach, creatures of our dreams and not of our waking lives, a possibility we will investigate further in our next chapter.

CRAFT: Elf Stones

The gods of the Viking Age (793–1066 CE) were divided into the Aesir (singular Áss), or sky gods, and the chthonic Vanir (singular Van), more or less. The Aesir were the dominant group, arriving to ride roughshod over the Vanir sometime in the Late Nordic Bronze Age, perhaps. Njord, Frey, and Freya, the most prominent of the Vanir, were gods of fertility and the dead. But just because they were gods of the underworld doesn’t mean they were frightful. On the contrary, the word “Van” is related to the Old English “win” meaning “friend.”

Of the two groups, the sometimes incestuous Vanir were more likely to have been at work already in the Early Bronze Age. It’s possible that the bride and groom in the sacred marriage were brother and sister, like Frey and Freya. Like the Egyptian pharaohs, the kings and queens of Old Elfland may have practiced royal incest in order to keep all that wealth and land circulating within a very small family circle. The whole process of raising the mounds may have been to remind the nonroyal populace that the rulers who lay within them were children of the gods, just as the kings of both Sweden and Denmark would later claim to be descended from Odin or Frey.

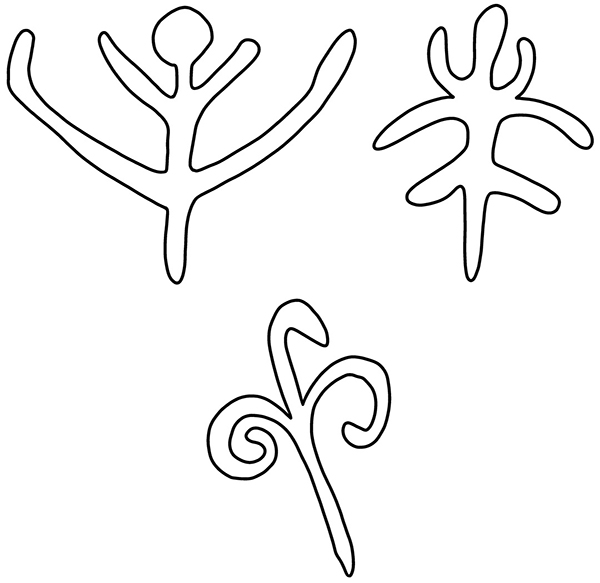

In the following pages, I present some of the cult symbols the mound folk used to honor or petition the Vanir. They’re all quite simple in design. The rock art of the Nordic Bronze Age was not chiseled as the ornate rune and picture stones of the Viking Age were; they were pecked into the surface of the rock with a hand-held stone, a much more tedious process than carving. It was so laborious that we can be sure there is nothing on those bowl stones, rock faces, and cover slabs that did not absolutely need to be there.

In this craft, you’ll be painting the symbols on the stones, so you’ll have a much easier time of it. Please do not apply your paints to a stone that’s already rooted in the landscape. By all means bring it gifts of milk, bread, berries, tallow, or beeswax, but do not alter it permanently. The dwarves are famous for popping in and out of stones and sometimes even leading the hero through the glittering halls within. You wouldn’t want to impose your decorating choices on a stone that’s already inhabited.

You will need:

Some small, smooth stones, possibly but not necessarily borrowed from the train station parking lot across the street

White or black acrylic paint

Paintbrush

Gold or silver metallic paint markers

Coat your stone with either black or white paint. When dry, draw on your chosen symbol or symbols (from the following pages) with the metallic paint marker. Don’t worry about irregular surfaces: they will make your piece more interesting. I like silver on black to make me think of the moon and the sparkling silver brooches that a nineteenth-century north German bride would have worn on the breast of her black woolen Sunday dress. Gold on white is appropriate for Winter Nights through Yule when we need to be reminded that the bright sun is indeed coming back someday.

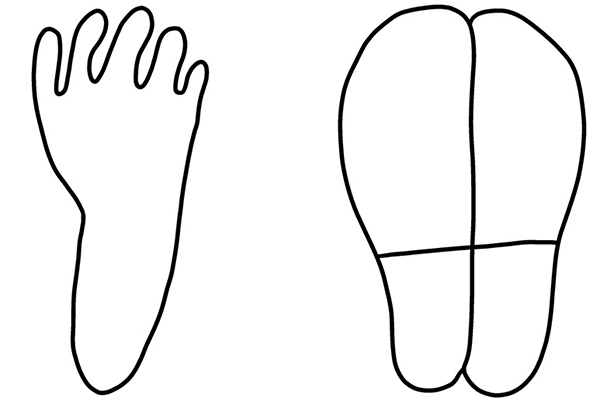

Footprint

There is a funny story about how the goddess Skadi chose the god Njord for her husband by his feet alone. She’d been holding out for the beautiful Balder, but Njord had the prettiest feet. Njord was a god of the sea and the winds. If some of the footprints we see on the stones are his, they were probably reddened by seafarers before they embarked on their journeys.

Why are footprints so powerful? Perhaps because they persist long after the person who made them has passed on, either down the road or into the next life. In chapter 23 of The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki, the character Elk-Frodi stamps on a stone so hard that it creates a deep depression. He promises his brother Bodvar that he will swing by from time to time to check on the print. If he finds it full of blood, he will know his brother has died by violence and he will avenge him. Elk-Frodi is only half human. The other half—the bottom half—is elk, so it’s actually a hoof print he makes. Still, this episode seems to echo the idea that the act of reddening a footprint in a stone could spur a god to action.

Frodi and Frotho were mythical Danish and Saxon kings. Their reigns were marked by peace and prosperity and their bodies revered in death. They were said to have lived so far back in the beforetime that they may have been the god Frey himself, as worshipped during the golden days of the Middle Bronze Age. Their names mean “fruitful one.” Frey, who, like many of the figures on the rocks, was famously depicted with an oversized phallus and was first and foremost a fertility god. He was responsible for bumper crops, and, when he chose, he could shower his followers with gold. Whether the mound people knew him as Frey or by some older, non-Indo-European name, many of the footprints are probably his too.

Sometimes, the prints are of bare feet. Others look oddly modern, as if some city-bound professional had stood on the stone in his hard-soled leather shoes, waiting for a train. This image is actually thought to represent a pair of sandaled feet with thongs wrapped around the instep.

We tend to assume that those who made the offerings believed the prints had been left by a god or elf walking over the stone, but the literature offers a different possibility. When a dwarf disappears into his stone, the last part of him the hero sees are the soles of his feet.

I like the one footprint alone, like this one taken from an Iron Age Danish cinerary urn. The “businessman’s shoes” are from a cluster in Scania in Sweden.

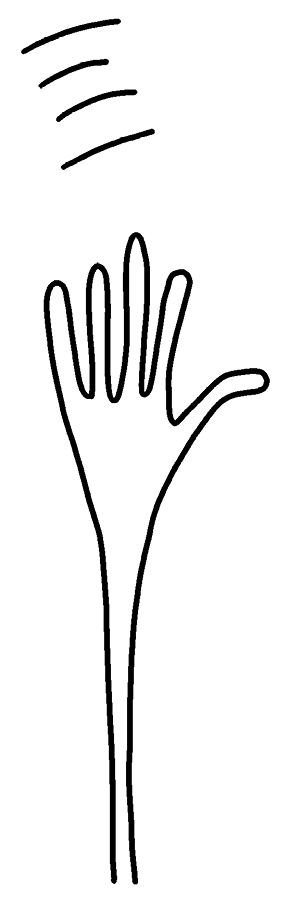

Hand

There are a dozen or more footprints for every handprint carved on a southern Scandinavian rock. At first, this surprised me. To the artist’s eye, the handprint is more graphically striking, more “intelligent,” than the footprint. The inked footprints of a newborn are presented to the proud parents at the hospital, but when the child gets to kindergarten and learns to talk and draw and build things, it’s a plaster handprint the parents get for Christmas.

Actually, the hands are there on the rocks, but they’re usually attached to lively stick figures. These hands are ridiculously large in relation to the body. They are held out to either side of the little round head with all the fingers spread. If these spread hands are the worshipper’s way of expressing reverence for the radiant sun, it would explain why we don’t see more lone handprints, for the sun is much more effectively represented by the spoked wheel.

And then there are the hand stones, twenty-seven of them, found scattered across Old Elfland from Denmark’s Zealand to Sweden’s Bohuslän and Norway’s Østfold. They were not carved in situ but on portable slabs about the size of small shields. Most of them served to cover the stone cists in which human ashes were placed, but those from Zealand were found at the site of some sort of cult center rather than a grave.

All the hand stones look pretty much the same. The double-

jointed thumb is always on the right. Four strokes above the hand are not incidental; they appear on all the hand stones. Most date from 1100–500 BC. The only thing we really know about them is that they had something to do with a new religion or a new sector of the old religion that was pushing for cremation. The fact that the hand is not disembodied but attached to a forearm means the artist wanted us to know where it was coming from: below. A hand thrusting itself through the earth of the grave is a gesture of the revenant, but the bodies in these graves had already been reduced to ashes. Some scholars believe the upraised hand signaled the expectation of rebirth. P. V. Glob thought the five fingers plus the four dashes equaled the nine months of gestation.

I like the hands because they’re so skinny and weird-looking. They remind me of the day I brought the first ultrasound image of my second baby into work. It was too soon to tell if the fetus was a boy or a girl. All I could do was point to the tiny skeletal hand and say, “Look! It’s an elf!”

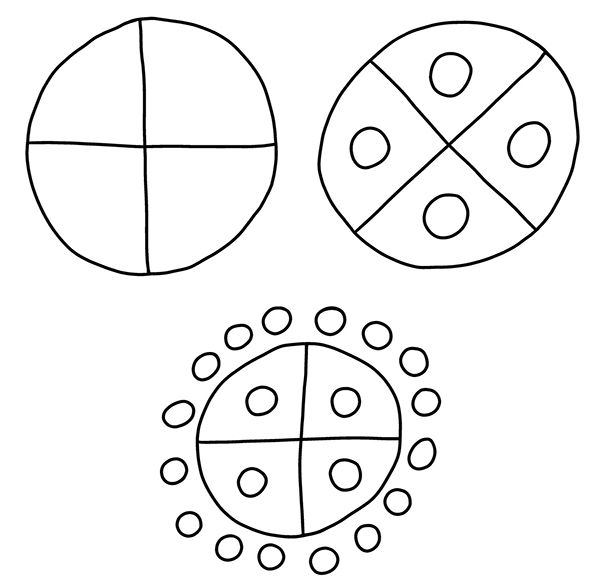

Sun Wheel

What came first, the sun wheel or the cart wheel? Since petroglyphs are hard to date, we can’t be sure. Did the first farmer to see a cart rolling across the moor say to himself, “Look at that little house running along on four suns!” or did another farmer pause before his own cart one day and say to himself, “A wheel is round. It turns. Its spokes radiate out from the center. How like the sun!”?

Sun wheels come in several varieties, from a simple circle divided into quarters to the elaborate example from the Danish island of Bornholm. You can paint these on your stones, or if you have the space, you can draw a large circle with sidewalk chalk and substitute tea lights for the dots.

And then there’s this one from Tegneby, Sweden. Am I absolutely certain that it represents the sun? I am not, though John Lindow calls it a “possible sun disk.” 22 The Tegneby disk is very wonky-looking, kind of like the Little Prince’s planet overtaken by baobabs. I have made mine a little more regular while trying to preserve the careless charm of the original. Like the original, it has only seven branches, not eight as one might expect.

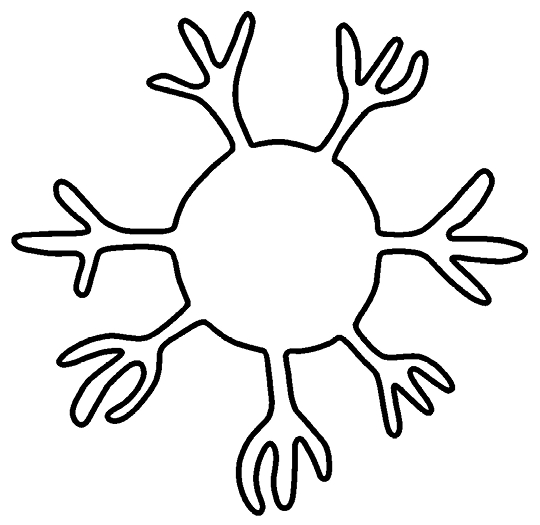

Tree

Nowadays, it’s considered entirely normal to decorate trees at Christmastime, not so much at Easter. But, in fact, Eastertide trees and Maypoles are by far the older traditions. In the Nordic Bronze Age, a budding or flowering branch was part of the springtime fertility rites. There’s one in the hand of the ploughman pecked on a rock from Litselby in Bohuslän. To see him for yourself, turn to plate 60 of P. V. Glob’s The Mound People where he is identified as “phallic man ploughing.” In Chariot of the Sun, Peter Gelling agrees that the fellow in question may be wearing “large artificial genitals for the occasion” 23 of plowing the first three furrows in the earth. Could this be the god Frey hard at work or just an ordinary farmer who’s excited to be out in the fields again after the long dark winter?

All in all, the branch he holds is not the best of Bronze Age springtime cult trees. I have found some more striking examples sprouting from images of ships. What are the trees doing aboard the ships? Perhaps these ships were the first to slip out of the underworld, laden with gifts for the living, as soon as the waters had thawed. The tree with the round knob on top is from Östergotland; the other two are from Bohuslän. Both sites are in Sweden.

SPELL BREAK: A Slice of Bread

On the whole, the elves in the Danish stories are not all that threatening. They and their later Danish countrymen had been neighbors for thousands of years and they were distant blood relatives too. Usually, each group knew what to expect from the other. Towering over wood and moor, the elves’ houses were plain to see, so meeting up with them was never much of a surprise.

The folktale “Playing with the Children of the Mound Folk” 24 was collected on the Baltic island of Bornholm—a realm of granite cliffs, forests, and standing stones—in 1892. It very specifically takes place “to the south of Gudhjem.” 25 The story’s title is misleading because the children are ordinary farm children while their singular playmate, a hungry little girl, is the stranger. It is not clear how we are supposed to know the little girl is a child of the mound folk. Is she wearing a string skirt? Is her hair stained a dark tannin brown? Do bronze or golden hoops swing from her ears? Perhaps there is a bluish cast to her skin?

Of course, if her home address is the nearby Hestestenene or “Horse Stones,” a group of four standing stones on a daisy-strewn green overlooking the sea just west of Gudhjem, then she might be a child of the Neolithic. As such, she would not have known gold or bronze or even horses. According to Bornholmer lore, the Horse Stones mark the place where a newlywed couple and their horse-drawn carriage crashed into the sea. Sacrificial bridegrooms and horse-drawn chariots are very much the stuff of the Nordic Bronze Age, so perhaps the ancient Bornholmers were accustomed to sacrificing the bride too. While most of the island’s monuments are much older than the Bronze Age, there are also plenty of stones bearing the pecked-out images of footprints, ships, and sun wheels.

Whether she is a Bronze Age princess, a Neolithic chieftain’s daughter, or neither of these, the little girl always seems to arrive on the farm around snack time, and she is always given a small piece of bread. So things go, until one day the mother of the farm children offers the girl a large slice of bread on the condition that she tell her where she lives. Is the farmwife looking for confirmation that the girl is, in fact, an elf? Perhaps she just wants to meet the little girl’s mother, and so she does, because just at that moment a “strange woman” 26 pops up to scold the farmwife: “If you want to give, then give, but don’t ask questions of an innocent child.” 27 She takes the little girl away with her and the farm children never see either of them again.

Curiously, the social roles are reversed in this story. Usually, it is the otherwordly character who offers a gift or at least the promise of riches to the mortal. Here, it is the mound child who receives conditional charity from a mortal. The mound folk of Gudhjem have obviously fallen on hard times. Not only have the Bornholmers converted to Christianity; the island has become famous for its many little round churches. How is a mound person supposed to make ends meet in the face of this upstart new faith that frowns upon the traditional sacrifices? Yes, the elves are having to rely on handouts, but they are still a proud people. A gift freely given was all right, but an offering with strings attached was an offense.

Just for the fun of it, I tried reading this story once more as if the title “Playing with the Children of the Mound Folk” were spot on. It’s a very short story, taking up a little more than half a page. Nowhere in it are the little girl or the offended woman identified as mound folk or as elves. They are described only as “strange.” But surely we appear as strange to the elves as they appear to us. Could it be the “farm children” are the children of the mound folk and a mortal girl has strayed into their yard to play?

There are plenty of stories about elves making hay and moving their cows from one pasture to another, so there is no reason to believe the mound folk of Bornholm did not keep farms of their own or have numerous children to help with the chores. The little girl’s mother, not realizing where her daughter had been wandering off to every day, finds her at last and catches her just as she is about to bite into a large slice of elven bread. Everyone knows that if you eat their food, you must stay with the elves forever. Understandably distraught, the mother whisks her little girl away before the mound mother can claim her.

All water under the bridge now. As I said, this story was collected in 1892 and was probably inspired by events that had happened at least a hundred years before. Whichever side of the veil they started out on, those children are now all long dead and are free to play with one another if they want to.

18. Glob, The Mound People, p. 98.

19. Because they were propelled by oars, not sails, they are technically boats, but if the term “ship” was good enough for Glob, Gelling, and Davidson, it is good enough for me.

20. Tolkien, Tolkien On Fairy-Stories, p. 32.

21. Ibid.

22. Lindow, Norse Mythology, p. 271.

23. Gelling and Davidson, The Chariot of the Sun, p. 79.

24. Kvideland and Sehmsdorf, Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend, p. 233.

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid.