LighTs in

the ForesT

Consider the story of the reluctant convert Koðran. In the Saga of the People of Vatnsdal, a story about events unfolding in the tenth century, we are told that Koðran and his wife were among the first Icelanders to be converted to Christianity by a visiting German bishop. According to this version, they “accepted the faith and were baptized at the outset.” 28 But two other sources, Kristni Saga and Thorvalds Thattr viðforla (“The Short Tale of Thorvald’s Travels”) tell a more interesting story. In these versions, Koðran confides to his son Thorvald (who for some reason is unschooled in the family’s traditions) that he cannot accept the new faith because he does not wish to betray his spámaðr.

The spámaðr, for his part, regards the bishop as a rival for Koðran’s loyalty, as indeed he is, and makes his displeasure at the visit known. The term “spámaðr” could be interpreted simply as “seer,” but this is no human fortuneteller; he lives inside a stone and appears to Koðran only in his dreams. Koðran and his family have a good thing going with this creature of the landscape: he can see into the future, as the spá in his name indicates, counsels Koðran accordingly, and keeps an eye on the cows.

One can’t help but root for the spámaðr. Koðran, however, allows the bishop to pour holy water over the stone which is his guardian spirit’s abode. That night, the spámaðr appears to Koðran in his dreams, telling him how his little spá children have been scalded by the holy water now leaking through their roof. Cold-hearted Koðran allows the bishop to repeat his efforts, and finally the poor creature and his family must pack up and look for a new home, but not before appearing to Koðran once more to complain of the unfairness of it all.

Before the arrival of the bishop, the spámaðr had been quite easy on the eyes. Now, he is “dark and hideous to behold.” 29 His nicer clothes have been ruined by the indiscriminate sprinkling of the holy water and he wears only a wretched black hide. Is the spámaðr the spirit of one of Koðran’s ancestors or an indigenous one? Although both Inuit hunters and Irish monks had passed through, the permanent settlement of Iceland did not begin until AD 850. There were no cairns, artificial mounds, or cup-marked stones in Iceland. Nevertheless, the Norse settlers perceived the place as awash with spirits akin to those they had left behind in their old homes. But what concerns us most is not where the spámaðr came from but how he communicates with Koðran: in his dreams.

Now if I had been that spámaðr, I might have tried to appeal to the bishop directly, to appear to him in his dreams in my loathliest form yet and chase him off my farmstead. But it was only with Koðran that the spámaðr had a long-standing personal relationship, only Koðran who had offered him sacrifice, so it was only to Koðran that he could appear. As far as the bishop and the clueless Thorvald were concerned, the spámaðr did not even fully exist.

Such “dreams” in which elves appear can also be courted in the daytime. In Swedish Legends and Folktales, John Lindow very helpfully identifies those conditions under which people were likely to see or to believe they had seen that which normally goes unseen. If one’s vision were obscured by darkness, mist, or the glaring brightness of noon, if sound were distorted as by an echo, or if the witness were already afraid, an encounter with elfkind (or at least the perception thereof) was more likely to occur. But there is one more important ingredient: the witness’s preconceived notions about what might be out there in the first place. And those notions are provided by the culture to which he or she belongs.

Toward the end of chapter VIII, “Flies and Spiders,” in The Hobbit, Bilbo and the dwarves are perfectly set up for an elven encounter. “At that very moment, Balin, who was a little way ahead, called out, ‘What was that? I thought I saw a twinkle of light in the forest.’ ” 30 As they near it, the twinkle becomes a sumptuously dressed party of elves enjoying a torch-lit feast. Bilbo and the dwarves are lost in the darkest forest of all: Mirkwood. They have had little to eat except for a nasty bit of black squirrel. In Middle-earth, of course, elves are real, but this is only an apparition, one which disappears as soon as Bilbo stumbles into the circle of light.

When Bilbo later wrote of the adventure in his memoirs, he would make the next hobbit who read it much more likely to perceive the wink of sunlight on autumn leaves as torchlight illuminating an elven feast, especially if he, too, were hungry, lost and exhausted. Likewise, a young girl hurrying home through a Swedish forest at dusk would be more likely to interpret a mossy snag as a hill man simply because her mother had warned her to be on the lookout for the dangerous hidden folk. And if that person, whether hobbit or nineteenth-century Swede, went on to tell his or her story in turn, it would become part of the tradition.

John Lindow is a folklorist and academic. We can hardly expect him to climb out on a lichened limb and tell us that elves are real. Tolkien, while also an academic, went a little further. He was willing to concede that elves might just be “true” 31 and might even “exist independently of our tales.” 32 If that is so, then they will not have died with those of our ancestors who believed in them; they will still be available to us, a people who rarely if ever talk about elves.33 And if it turns out that elves are nothing more than the products of our imaginations, they are still no less “real” for it, just as dreams, cravings and thoughts are real and adhere to certain rules.

I find that dreams dreamt after a certain amount of stress are more likely to produce an encounter with elves. But don’t forget that you are a creature of your own time and place. Don’t expect to see Koðran’s black-cloaked spámaðr or a randy hill man in moss-stained frock coat standing at the foot of your bed. Those might not have been those spirits’ “true” forms either, for as Tolkien reminds us, “the trouble with the real folk of Faërie is that they do not always look like what they are.” 34

First, let’s define “stress.” I experience a special kind of stress when I am staring down a deadline. Writing the kind of books and articles I do, this stress can be especially conducive to dreams of Elfland. It’s as easy to get lost in research as it is to lose one’s way in Mirkwood. Many times I have left the path of a final draft to chase after a minor character in an obscure, untranslated saga to find myself hopping from textual tussock to textual tussock over the dark waters of a scholarly bog, dreading the appearance of corpse candles as the daylight fades.

Immersion in an exciting new subject can also bring about dreams of a heightened, elven crispness. I remember a magical dream I had one September while enrolled in a Japanese language class. The class was in the evening—not a good time for me because my brain likes to wrap things up around seven. I had recently developed a passion for Japanese folk toys, and during the day I was reading everything I could about kokeshi dolls and bean-jam-bun-boys, the library books a balm for not having the money to collect the toys themselves. One night I dreamt I was visiting my grandmother in the city of Kiel, towards the south of Old Elfland. The dream city had a very different vibe from the real Kiel in which she’d lived, the buildings taller and closer together, the streets more crowded. While exploring this bustling dreamscape, I stumbled on a little shop crammed full of papier-mâché spirit foxes, long-nosed goblin masks, and all the other toys I’d been reading about.

But what does this have to do with elves, you ask? Japan, of course, has its own branch of elfkind, like the spirit fox and long-nosed goblin who still receive offerings and are celebrated as toys. But there weren’t any actual elves in the dream—unless you count my grandmother, who was long dead by then and might have joined their ranks. She had always struck me as a very no-nonsense sort of woman, but according to my aunt and the books my grandmother left behind (Otfried Preussler’s Krabat and the darker short stories of Roald Dahl) she had a taste for the macabre. A slightly spooky career on the other side of the veil might have been just the thing to appeal to her. As an Irish mystic once confided to author W. Y. Evans-Wentz in The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries, “I think anyone who thought much of the Sidhe [fairies] during his life and who saw them frequently and brooded on them would likely go to their world after death.” 35

But the reason I have mentioned this dream is the feeling that it gave me. The atmosphere felt like that of Elfland or what Tolkien calls “Faërie.” I’ve had plenty of dreams about finding extra rooms inside my apartment or traveling somewhere I’ve never been, but those were just ordinary dreams. My dreams of Elfland usually begin in familiar territory before the setting gradually shifts to one of welcome unfamiliarity. My native worn-down Watchung Mountains suddenly look like real mountains: the streets scaling them steepen dramatically, and at the top of the ridge, instead of another row of box colonials, I find a stream in the middle of an almost Andean expanse of wilderness, waving stands of pampas grass on either side.

For several years, an abundance of tall yellow grass was the hallmark of my dream Elfland. Though it often fringed the trail of a hiker’s paradise, sometimes it was simply growing in a neighborhood I’d never been to before, one in which a child’s birthday party was taking place and to which, in the dream, I had to deliver a present. One time, it was growing next to a small red house. I wanted to own that house in the worst way, and when I woke up, I was disappointed to realize that I could never have it, not because I couldn’t afford it, but because it didn’t exist in this world.

The German island of Sylt in the North Sea is mostly coastline and therefore mostly sand, with long yellow beach grass waving from the hillocks overlooking the sea. Sylt, too, belonged to the Bronze Age culture of Old Elfland, and it was there that I first remember someone pointing out to me a Bronze Age burial mound. Before I started work on this book, I’d forgotten about the beach grass, but there it is in the grainy Instamatic photos we took on the trip. I like to think that the lasting impression of that grass was the gift of whatever elf resided in that mound, a gift that resurfaces now and again in my dreams.

My first elven encounter, however, was not a dream but a memory. At least, I have always perceived it as a memory of a lived event, not a dream. Still, I was very young when I first committed it, so who knows? And how much of a difference is there between the two, really? After all, Koðran’s spámaðr appeared to him only in dreams, but Koðran never doubted that their conversations had actually taken place. He even acted on the advice he was given in those dreams.

As elven encounters often do, mine took place in the liminal space between wilderness and human settlement, at the boundary of the phragmite-fringed wetlands and the muddy lots of a new housing development. A few of the houses were finished, others only framed. I was a preschooler, but for some reason, probably financial, my mother never enrolled me in what they called nursery school in those days. I didn’t mind. I was happy to roam the neighborhoods with my stay-at-home father, eating melted sugar and butter sandwiches beside one of the trails in the nearby swamp and exploring the residential streets at its edges.

It was while exploring the freshly tarred Crocodile Drive with my father that I spotted the children: a brown-haired girl and a brown-haired boy, both about my age, playing in a sandbox installed among the rust-brown rocks and swamp clay of their desolate new yard. We regarded each other in silence. They did not ask me to stop and play nor was I sure I would have wanted to. Soon, my father and I had passed them and gone up the hill to walk home again along the shoulder of the main road.

Though our encounter had been brief and uneventful, those children held a strange fascination for me. I wanted to see them again. I was to be disappointed, for later visits proved there was no Crocodile Drive—I couldn’t read yet, so my father relayed the street names to me. At least, I thought he had. There was, in fact, no street there at all, just hard-packed earth and a thicket of native laurel where the street, the house, and the sandbox had been. Over the course of the next ten years and more, the neighborhood expanded. New roads were built. I walked up and down them with my dog—I had a dog by then—but none of them were Crocodile Drive either in name or appearance or overall feeling. Since then, I have walked down streets in other towns that had a certain indescribable magic about them, but, unlike Crocodile Drive, I’ve always been able to find them again.

As I’ve already confessed, I was only about four years old at the time of my supposed encounter. I could easily have gotten my streets mixed up and transposed the children from one yard into another. I’m sure we saw plenty of other interesting things on our walks, so why do I remember those children, that sandbox, with such clarity? I can only say that there was something extraordinary about that street and those children, ordinary though they had looked. I would think of them from time to time long into adulthood, handling the memory carefully, confiding it to no one, knowing how fragile such things can be, how the edges blur with each telling. In writing about it, I know I am compromising it yet again, but you wanted to know about elves.

I didn’t think of my experience in elven terms until I read Sarah Ellis’ short story “Tunnel.” In fact, I can tell you exactly where in the story I was when I made the connection. Peering through the tangle of vines at the mouth of a drainage pipe that runs under the road, six-year-old Ib asks Kenton, the bemused teenage boy who is babysitting her, if the pipe leads to “that other place.” 36 To which Kenton asks, “What other place?” And Ib replies, “Where those other girls play. I think this goes there.” 37

I don’t want to ruin the rest of a very short story for you, but rest assured that “those girls” are no ordinary girls, and Ib’s later statement, “I don’t really like those girls,” 38 made a lot of sense to me. Did I like the children on Crocodile Drive? Not really. Nor did I feel they either liked or disliked me, which is all very much in keeping with Tolkien’s statement that “elves are not primarily concerned with us, nor we with them.” Rarely do they come right into the house, and when they do, they are not there to seek us out; they are merely passing through. They are probably even less interested when we are the ones passing through their territory, as I was that morning.

There is one more detail that supports the elvenness of my encounter. The house I saw near the sandbox children was like all the others in this new development: a yawning colonial revival with four or five bedrooms, a dressing room, playroom, and den—a mansion compared to the six-room Cape Cod that I lived in. In other words, these children were of a higher station than me, just as the elves in so many of the tales are more richly dressed, better spoken, and even prettier than us poor mortals who happen to run into them.

I don’t think it’s too far-fetched to trace this social disparity between us and the elves all the way back to the Bronze Age when, probably for the first time, there was a drop-dead obvious difference between the classes. Ethnicities were continuing to overlap, but whatever their origins, the privileged classes would have been taller and less rickety than the laborers. Back in the good old days of flint-knapping, no one would have glittered, no matter how rich they were, but by the Bronze Age, the elite could be identified not just by their glowing health but also by the spiked disks on their belts, the bronze swords at their hips, and the gold hoops in their ears.

There were only ever a handful of these scintillant swaggerers, a tiny upper class supported by a swollen and no doubt grumbling lower class who would depose them before the Bronze Age was over. I have mentioned that the bloodlines would have had to cross and cross again in order to produce the population that exists in northern Europe today. I doubt that many dairymaids or charcoal burner’s daughters were carried into the longhouses as brides. Better to fetch a noble bride from afar as the in-laws of the Egtved and Skrydstrup Girls did. No, the mingling of the classes must have occurred outside the marriage bed, behind the woodpile, on a lonely stretch of forest track as darkness closed in. The Nordic Bronze Age prince who, returning home in especially high or low spirits from a skirmish or inspection of his lands, spotted a not unlovely peasant girl along the way and decided to have his way with her would eventually become the hill man, elf king, or “fairy lover” of the medieval ballads and eighteenth-century folktales. Let’s take a look at him in action.

SPELL BREAK: The King of Hollow Hill

According to the editors of Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend, the story of “The Girl and the Elf King” 39 takes place on the small island of Bøgo in the Baltic Sea. Bøgo is not a lonely island; it’s surrounded by the larger islands of Møn, Zealand, and Falster, a wonderfully central yet private location, the perfect spot in which to bury an elf king—and bury one they did, back around 3700 BC. The king is no longer in residence. Nothing much has been found inside the passage grave known as Hulehøj, or “Hollow Hill,” except a few tools and pieces of pots. It seems, however, that our king of Hollow Hill was still active in the years preceding 1893, when this tale was collected.

Hollow Hill is not actually mentioned in “The Girl and the Elf King.” It is at the “Elves’ Moor” that a pretty young dairymaid disappears one day. She responds to no one’s call, and when the other girls finally find her there, she is in a daze and they must drag her home by force. She tells them how she fell under the enchantment of a “handsome man” 40 and how she had been unable to escape on her own. How far things went with this elf king the girl doesn’t say, but day after day she’s compelled to return to his embrace.

The elf king does not appear to be interested in making her his bride, for he releases her at the end of each day to go home with her cows. She doesn’t seem to be suffering; she’s just a little “bewildered” 41—but this elven dalliance is no doubt hurting her chances of landing a mortal bridegroom. Finally, someone in the village who knows about these things tells her how to break the spell. When next they meet, the girl must ask the elf king to turn around so she can see if he looks as good from behind as he does from the front.

She has to ask him three times before he will comply. And when he does, sure enough, his back is as hollow as the hill in which we are assuming he dwells. The girl likens his back to a baking trough, but it puts me in mind of an oak trunk coffin or one of the later more finished caskets the Scandinavian undead liked to haul around on their backs (see “Draug” in the Appendix). Of course, whoever the original owner of the passage grave was, he or she would have lived back in the New Stone Age, would not have been buried in a coffin of any kind and would never have glittered with gold or bronze as an elf king is expected to do. But a king is a king, and while he probably enjoyed a somewhat lower standard of living, he was of a much higher station than the nineteenth-century dairymaid.

It’s a similar state of affairs in the Norwegian tale, “Outwitting the Huldre Suitor with Magic Herbs,” in which an obnoxious huldre (see “Hidden Folk” in the Appendix) boy promises a Norwegian farm girl “wealth and luxury all her days” 42 if only she’d marry him. The girl outwits him with the help of another village elder, but he comes back to taunt her once more. By this time, the girl has married an ordinary fellow, given birth to a slew of children, and is having trouble feeding them all. Times are tough. The would-be huldre lover, who is apparently still just a boy, comes to her while she is hard at work gathering in the autumn harvest to remind her of the riches she has given up.

Would the elf king have eventually taken the Bøgo girl with him into his hollow hill and showered her with riches or with autumn leaves? I think not. I think he was only interested in a bit of fun. No doubt he already had a wife back in Elfland, one who may have been trying her luck with the woodcutters on the same island. Fortunately, our dairymaid has the last word. Once she has exposed him for the otherworldly creature he is, the elf king is forced to walk away.

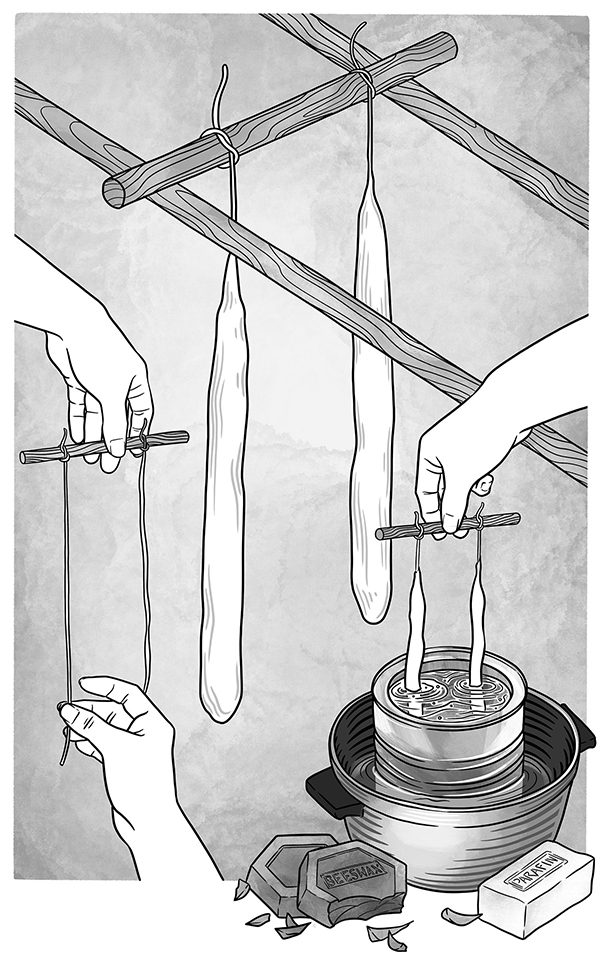

CRAFT: Elf Candles

There were no candles in the Nordic Bronze Age, though the mound people may have had the rushlight or rushdip, a kind of skinny pre-candle. A rushlight was the pith of the water-loving rush plant (genus Juncus) dipped several times in tallow. Autumn was the time to make rushlights and, later, candles, because there would be plenty of tallow to melt down after the slaughter. You, too, can make candles out of tallow, but be prepared for them to gutter liberally and not smell very nice. The elves are supposed to enjoy gifts of tallow, but I find beeswax an acceptable, sweet-smelling alternative.

One Old Norse kenning for the sun, álfröðull, which will be discussed further in Chapter Six, is sometimes translated as “elf candle.” These skinny little elf candles can be stuck upright in a bowl of sand where they will burn for about thirty minutes.

Beeswax comes in one pound blocks, but you need only fifteen ounces to make your candles. The leftover ounce goes in your birch soap, the recipe for which can be found in Chapter Eight. You can, of course, make entirely beeswax candles, but I like to mix beeswax with paraffin for a pale, slightly translucent candle. Amounts do not need to be exact as long as you keep more beeswax than paraffin melting in the coffee can. Too much paraffin will make your candles droopy.

You will need:

A sharp knife

A cutting board

15 oz. yellow beeswax

8 oz. paraffin

#6/0 or thinner square braid cotton wick

One coffee can

A pot large enough to comfortably hold the can

2 long dowels

12 short (about 6 in. long) dowels

2 kitchen chairs

1 expendable chopstick

With the sharp knife, start shaving off pieces of your beeswax on the cutting board. Place the shavings in the coffee can as you go. When the can is about half full, place it in the pot in a hot water bath. As it melts, you can add more beeswax and bits of your paraffin blocks. (It won’t all fit at once, but that’s okay because you’ll need to add more as you go.) This process will take a while. Keep the water hot but not boiling; you don’t want it splashing into the wax.

While the waxes are melting, cut your wick into seven-inch lengths. Tie them in pairs on the short dowels.

Place the two kitchen chairs back to back and use the two long dowels to make a rack. You might want to put some newspaper on the floor to protect it from splatters. Hang your wicks on the rack, ready and waiting.

When the can is filled almost to the top with melted wax, it’s time to prime the wicks. Submerge the first pair of wicks in the wax. They’ll want to float to the top. Push them under with the chopstick and hold them there until no more bubbles rise up. Remove them, hang them on the rack, and repeat with remaining wicks. None of the wicks will hang straight at this point. Don’t worry about it.

When all wicks have been primed, dip the first pair quickly in and out of the wax. Straighten wicks between your fingertips after each dip. Soon they will hang straight. Dip each pair about fifteen times for a 3⁄8" diameter base. Keep adding more wax to the can as you go to keep the level high.

When the finished candles are cool to the touch, cut them off the dowels and they’ll be ready to burn or store. Remove the coffee can from the water bath carefully, place on a towel, let harden, and store with a lid until your next candle making session.

28. Thorsson, The Sagas of the Icelanders, p. 265.

29. Battles, ”Dwarfs in Germanic Literature,” p. 48.

30. Tolkien, The Hobbit, p. 164.

31. Tolkien, Tolkien On Fairy-Stories, p. 32.

32. Ibid.

33. Yes, I know: Iceland is the exception. Icelanders talk quite a lot about elves.

34. Tolkien, Tolkien On Fairy-Stories, p. 31.

35. Evans-Wentz, The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries, p. 68.

36. Ellis, The Road to Hel, p. 6. Ellis’ stories are all pure fiction, as far as I know, but her book Back of Beyond: Stories of the Supernatural recalls the spirit of the folktales recounted in Barbara Rieti’s Strange Terrain: The Fairy World in Newfoundland, from which Ellis draws the epigraph for her collection.

37. Ibid.

38. Ellis, The Road to Hel, p. 9.

39. Kvideland and Sehmsdorf, Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend, p. 216.

40. Ibid.

41. Ibid.

42. Christiansen, Folktales of Norway, p. 132.