Durin’s Day

In Ireland, the hollow hills have been opening on the eve of All Hallows since the Middle Ages, at the very latest. But that’s Ireland. What was happening in Old Elfland at the end of October? By the Viking Age, the descendants of the mound people were celebrating something called “Winter Nights.” There’s no reason to believe that Winter Nights was a newfangled holiday, just as there was nothing particularly novel about the Vikings’ gods or home lives. At this time, the Scandinavians were channeling all their innovative thinking into their ships, which were now expertly rigged and aggressively seaworthy. They had developed a passion for taking those ships as far out to sea as they could, though that impulse, too, echoed the riverine wanderlust of their Bronze Age ancestors.

The ancient feast of Winter Nights is known to us only from a few mentions in medieval manuscripts. It was held in mid to late October, the most sacred time of year for the festival’s pastoral celebrants, for this was the season when the herds were brought in from those dangerous troll-ridden summer pastures. Only the best and the brightest of the livestock were kept through the winter. The rest were slaughtered, salted, rendered, and served up fresh to the hordes of guests, both living and dead, who descended on the hall. What better time for the tribes to gather and make plans for the coming year? As at the Irish Samhain, a multiday festival held when the Pleiades reached their highest point in the night sky, prophecies were spoken and engagements might be announced, leaving plenty of time for a Yuletide wedding.

In 2002, I happened to be in the northernmost German province of Schleswig-Holstein on Halloween. It didn’t seem right. There were pumpkins for sale at the farm stands, but the nubbly German Kürbiss is the color of a blood orange. It can even be green. It’s a far cry from the smooth golden American pumpkin that all but begs you to carve a scary face into its rind. Just a few years before, the Kürbiss had been for pickling only. Now, children were urged to carve them into goblin-faced lanterns, a privilege which had previously been reserved for the turnip, and only for St. Martin’s Day (November 11), not for Halloween.

There was a threat of trick-or-treating in my aunt and uncle’s suburban neighborhood. My aunt prepared some little parcels of cookies, just in case, then we waited to see what would happen. A few polite takers appeared at the door over the course of the evening. The transactions were completed without incident, but I could tell that, behind the smile, my aunt was thinking, “What nerve!” Earlier, the sexton of the local church, having gotten wind of this upstart tradition, remarked that when he was a boy, children had gone begging at the proper time: New Year’s Eve.

With the coming of Christianity, Winter Nights was eclipsed by All Saints’ and All Souls’ Days. Centuries later, when these Catholic holy days lost their importance in the Protestant north, the dead began to limit themselves to visiting their families only at Yule. German school children do get a week off in October, but the break has no religious significance; it was originally so they would be on hand to help harvest the potatoes, a New World species that soon became a staple of the German diet. Some of them do still help out on the family farm at this busy time of year, but the rest hit the Mediterranean beaches.

The old Scandinavian observance of Winter Nights may have survived, in a way, as an ink and paper holiday. In C. S. Lewis’s The Silver Chair, we find the so-called gentle giants of Harfang preparing to celebrate the Autumn Feast—on the menu: Marsh-wiggle and young Briton. And in Tolkien’s Middle-earth, “the first day of the last moon of Autumn on the threshold of winter” 43 is Durin’s Day, the dwarvish44 New Year’s Day. Neither author was short on imagination, but since they were both influenced in many ways by ancient pagan tradition, I think it reasonable to assume that they drew on what they could glean of the old autumn festival when creating their own fictional holidays.

Our winter starts on December 21, but for the ancient Germanic peoples (as well as for Tolkien’s dwarves and hobbits), it began in October already. In keeping with Germanic tradition, Tolkien called the tenth month of his Shire Calendar 45 “Winter-filth.” Winter-filth has only thirty days, so Durin’s Day cannot fall on our Halloween. In The Hobbit, the dwarf Thorin Oakenshield goes on to explain that, on Durin’s Day, “the last moon of Autumn and the sun are in the sky together.” 46 It is this phenomenon that allows Thorin to unlock the secret door in the Lonely Mountain. Just before the last ray of the sun hits the door, Bilbo spots a “thin new moon” 47 just above the horizon. So if you want to put a Tolkienian spin on your own dwarf-centered autumn feast, keep an eye on the calendar to see when October’s crescent moon will be sharing the sky with the setting sun. (The new moon is the phase in which the moon is not visible at all, so I’m assuming Tolkien meant the first trace of the crescent moon.)

Whatever kind of celebration you decide to hold, stand firm: the stereotypical witch figure is allowed to riot through the whole month of October, so your friends, family, and neighbors can hardly complain if you wish to dedicate just one day to the dwarves.

Who or what exactly is a dwarf and how does he differ from an elf? Durin, lord of the dwarves, looms large in the history of Middle-earth. Tolkien drew the name from the Old Norse poem Völuspá, in which he is said to be the most famous dwarf after someone named Motsognir. The Völuspá does not say why. The Hobbit’s Dwalin, on the other hand, is just another dwarf in Thorin’s company, but his namesake, Dvalin, makes quite a career for himself in the Old Norse literature. Dvalin was one of the dwarves who crafted Freya’s mysterious golden accessory, Brisingamen, and who got to sleep with the goddess as payment. In Fáfnismál, he commands his own troop, and it was he who acquired the runes for his race. Durin and Dvalin appear together in The Saga of King Heidrek the Wise to forge the cursed sword Tyrfing, though in the poem “The Waking of Agantyr,” only Dvalin is given the credit.

Mostly, Dvalin stands for dwarfkind in general. Some of the norns are described as “Dvalin’s daughters.” Poetic kennings for the sun include, oddly enough, “Dvalin’s plaything,” and, more understandably, “Dvalin’s deluder,” since dwarves caught out in daylight quickly turn to stone. Unlike Tolkien’s Durin, Dvalin did not have his own day.

If you have already looked up “dwarf” in the appendix, you know that the dwarves, while not quite elves, are nevertheless members of elfkind. Winter Nights was an unspecified number of evenings long, and one of those evenings was devoted to the elves. The Álfablót marked the onset of winter, but an impromptu Álfablót, or “sacrifice to the elves,” could be made whenever needed. “Go and sit on an elf mound,” was the prescription given whenever fertility, guidance, inspiration, or healing was needed. By the twelfth century, this prescription had been reversed. In the Danish ballad “The Elfin Howe,” the now-Christian audience is warned not to “Tarry … by the Elfin Howe / Nor lie down to slumber there.” 48

But before and even during the piecemeal conversion of Scandinavia, contact with the elves was considered to be so beneficial that rituals were performed atop elf mounds that were not, strictly speaking, elf mounds at all. In Kormáks Saga, the sorceress Thordis advises Thorvald (not to be confused with the Christian Thorvald Koðransson), who is suffering from a slow-healing wound, to propitiate the elves by making them a meal and reddening the hill on which they reside with the blood of a bull slain by Kormák, the guy who inflicted the wound in the first place. This is Iceland, so the hill to which Thordis directs Thorvald can only be a natural hill that is presumed to be the habitation of elves because it resembles the true elf mounds of the Viking homelands.

The seasonal Álfablót took place at home on the farm, just one of several Winter Nights events. We know startlingly little about it. We know some kind of sacrifice was made, probably of livestock since this was slaughtering time. Secrecy surrounds the observance, but that may only be because the single sketchy report we have of an Álfablót comes from a Christian scald who was firmly denied entrance to one in 1018.49

Another Winter Nights event was the Dísablót, the sacrifice to the dísir. Like the dwarves, the dísir are also members of elfkind, though rather haughty ones. You might think that two “races” more disparate than dwarves and dísir could not be found. The vast majority of dwarves that we’ve heard of are male. They inhabit caves, boulders, and rocky spaces. They work with their hands, creating such masterpieces as the god Frey’s collapsible ship Skiðblaðnir, his gold-bristled boar Gullinborsti, and Odin’s magic ring, Draupnir. Dwarves were known to men and gods by their personal names, but, despite this intimacy, they expected little, if anything, from mankind.

The dísir (singular “dís”) were nameless ancestral goddesses who influenced the family fortunes in return for regular sacrifices, preferably of the bloody kind. They are exclusively female, and rather than toiling at the workbench, they functioned in another dimension entirely. They were the ones behind the curtain, tugging at the strings of destiny. Unlike the dwarves, the dísir concerned themselves very much with the doings of men, but they were no soft-hearted fairy godmothers. Nor could they be side-stepped.

In the Saga of Olaf Tryggvason, an Icelander named Thorhall foresees that someone on the farm is going to be sacrificed at the upcoming Winter Nights. Thorhall and his contemporaries are among a people who are in the process of moving away from paganism and human sacrifice and towards Christianity. Sídu-Hall, the owner of the farm, had decided earlier not to hold the traditional Dísablót at all, but now, just to be safe, he slaughters a bull in hopes of fulfilling the prophecy without shedding human blood. That night, while the family is huddled inside, there comes a series of loud knocks on the door. Sídu-Hall’s son, Thidrandi, is the only one reckless enough to answer it. Seeing no one at the door, Thidrandi steps out into the yard and is transfixed by the sight of nine black-clothed women sweeping down from the north and nine women in white riding up from the south. To make a short story even shorter, the white-clad women arrive too late to save Thidrandi, and the black-clad women make mincemeat of him. The scholarly consensus seems to be that the black figures were the family’s own dísir, upset at not receiving the sacrifice they had ordained, while the white figures were the bearers of the new faith. So this was one round that Christianity lost in Iceland.

Closely related to the dísir were the valkyries, but a valkyrie did not serve the whole family. She attached herself to just one member: the hero. She helped guide him on his journey and decided when that journey was over. I don’t think anyone who enjoyed the attention of a valkyrie ever died of old age, for the valkyries made sure he was cut down at the height of his powers, not unlike the sacred bridegroom. There were many valkyries and, like the dwarves, they were known by their personal names.

Though the dwarves were not contractually bound to the hero as the valkyries seem to be; they often pop up in the literature to offer the hero a bit of wisdom or an important gift. The dwarves Durin and Dvalin forged the sword Tyrfing for Svafrlami, proudly presenting it to him and cursing him with it in the same breath. The dwarf Regin forged the sword Gram for Sigurd the Dragonslayer, though Sigurd had to coax him to do a proper job of it. And then there was the German dwarf Baldung who gave the hero Dietrich a magic root with which to vanquish a wild man. There was even a case in which a dwarf, Sindri, lent the hero Thorsteinn the use of his own dís on a journey.

And let’s not forget Princess Alfhild of Alfheim who, in the Saga of King Heidrek the Wise, reddens the altar of her family’s dísir at Winter Nights. Though the altar is not described in the saga, it was probably a cup-marked stone somewhere on the property, perhaps the same stone at which the elf-named Alfhild sacrificed to her distant elven relatives at other times of the year.

Elfland often eludes us, but we spend our whole lives within a dwarf-defined space. The gods formed the dwarves from the maggots infesting the flesh of the giant Ymir. Shortly thereafter, they used Ymir’s skull to make the dome of the sky and appointed four dwarves—Northri, Suthri, Austri, and Vestri—to hold it up. Even if you don’t speak Old Norse, you probably recognized the names of the four cardinal directions. So unless we leave Earth’s atmosphere, we are always in Dwarfland.

Don’t be surprised that you can’t see these dwarves, for dwarves have the power of making themselves invisible. Sometimes it’s through the use of a ring, but more often it’s a Tarnkappe or Tarnhut, a magic hood or hat. The Tarnkappe, like the dense woolen caps worn in the Nordic Bronze Age, also protected the dwarf from sword blows.

It is generally agreed that dwarves are not naturally handsome. After all, they’re made out of maggots, and they were only invited into Freya’s bed because the goddess was so desperate to get Brisingamen from them. If a dwarf wanted to look good, he could use magic to make himself attractive to gods and humans. Ugliness, or loss of glamour, was the sign of a dwarf in distress, like Koðran’s wretched spámaðr. If the dwarves have learned to use the internet (and I don’t see why they wouldn’t have; they’re very clever) then they’re probably all over the dating sites. Watch out for them, but be respectful: you never know when you might find yourself in need of a magic root or a really fine sword.

CRAFT: Paper Skínfaxi

Take one look at the thirteen-inch-high Trundholm Sun Chariot and I’m sure you’ll agree with me that it could only have been made by dwarves. Who else could have done such fine work back in 1400 BC? Whatever cult commissioned this singular piece must not have subscribed to the idea that the sun traveled back to the east on a ship through the murky waters of the underworld, because this chariot was designed to carry it both ways. The day side of the disk is covered in fragments of incised gold foil while the night side is plain dark bronze, though also worked with spirals as if it, too, were meant to be seen. The metal horse hitched to it is decorated with delicate lines and dots, including the suggestion of a mane.

The Trundholm horse and chariot were plowed out of the ground in 1902 by an unsuspecting Danish farmer on the large island of Zealand. The date of 1400 BC is only approximate and is actually a little early for such a chariot to be trundling over the Danish moors, but only by a few hundred years. I can’t tell you much more about the chariot, but I can tell you that the horse’s name is Skínfaxi.

Or is it? Skínfaxi, “shining mane,” is the horse who pulls “Day” across the sky in several lines of Old Norse poetry. As far as we know, Skínfaxi works alone. The first fifty or sixty times I looked at pictures of the Trundholm horse, I assumed that he was working alone too, but, as Peter Gelling points out in Chariot of the Sun, only one rod seems to attach the traces to the axle of the carriage. Could there once have been another horse on the other side of the rod, helping to pull the load? The chariot is now displayed with the lone horse riding atop the rod, looking slightly awkward and even a little embarrassed.

The chariot did not come out of the ground intact. Pieces are still missing, so it’s impossible to know exactly how the whole thing was put together. A similar ensemble was pulled from a mound in Helsingborg, Sweden, in 1895 and included not one but two little horses. Elsewhere in the poetry, the sun is indeed drawn by two horses, Árvak and Alsvin. Árvak and Alsvin belong to a very old Indo-European tradition of twin horses/brothers who summoned the dawn. To the Vedic Hindus of 1400 BC, they were the “Ásvins.” In pulling the sun chariot over the lip of the horizon, these twin horsemen necessarily precede the dawn, so they may represent the first two rays of light that pierce the night before sunrise. Recently, archaeologists have recovered a few more pieces of the Trundholm Sun Chariot but so far no second horse.

If the Trundholm version of Skínfaxi did in fact pull Day through the skies above Old Elfland all by himself, I imagine it was his alter ego, Gandalf’s Shadowfax, that drew it back through the caverns of the underworld at night.

There are no receipts to prove the dwarves forged Skínfaxi or any other horse, but they did make a gold-bristled boar for the god Frey. He was so pleased with it that I can’t imagine he didn’t also order up a few fine steeds. During the Iron Age, Frey was accustomed to receiving sacrifice in the form of horses at Lejre on the island of Zealand.

The following project makes a footloose and fancy-free Skínfaxi, freed from his traces after a long day’s work.

You will need:

Black card stock

“Antique Gold” craft paint

Square-tipped paint brush, at least ½ inch wide

Scissors

Glue

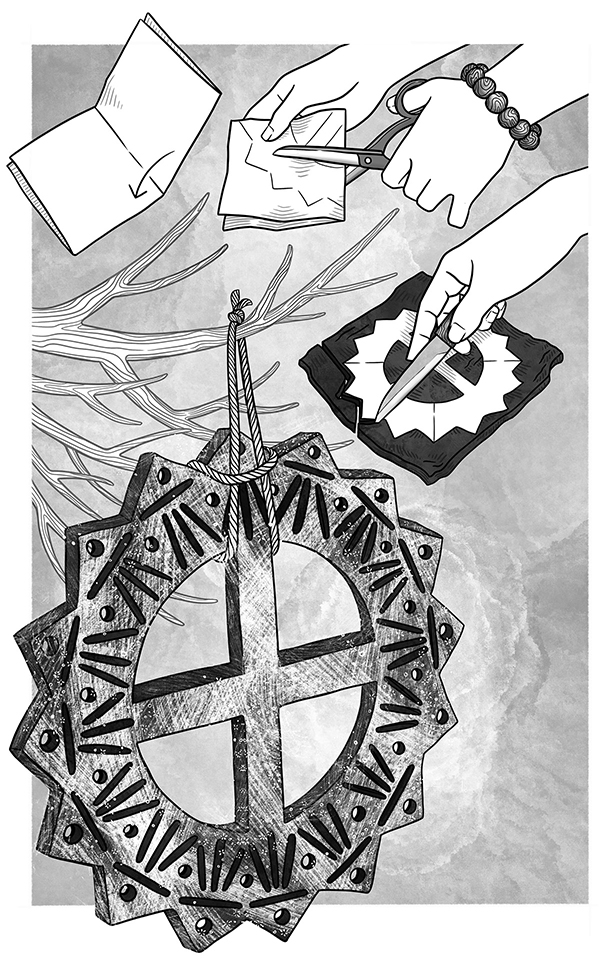

Paint the card stock gold using a dry brush. You want minimal coverage, with plenty of the black card showing through. Let dry.

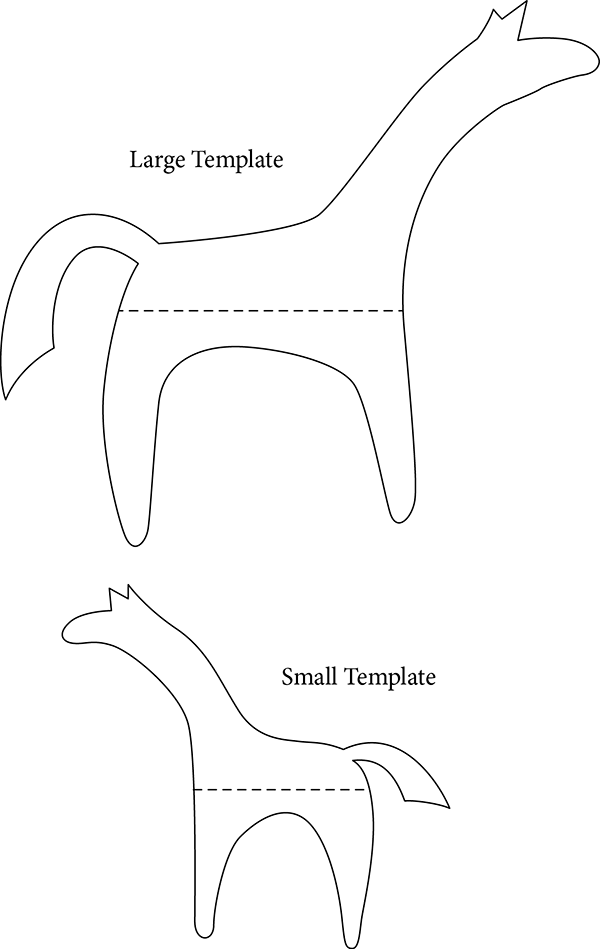

Choose either the small or the large horse template. Copy, cut out, and trace two horses on your card stock. Remember to turn the template over for the second horse. Cut out and crease as shown by the dotted line on the template. Glue the two halves of your horse together above the crease with the gold side of the paper on the outside. Stand him up on your workspace while you make him a companion.

CRAFT: Elf Cross

Yes, I know: this is the dwarf chapter, but as you will see throughout this book, the branches of elfkind have always been tangled. Since the dwarves are known for their skill in metallurgy, I’m putting this craft here. The Swedish ellakors or “elf cross” usually took the form of a thin disc of silver engraved with an equal-armed cross. You didn’t order it from a catalog; you didn’t exactly “order” it at all; and you had little say about what the finished product looked like.

First, you had to gather nine pieces of silver from nine different people, old buttons and buckles they wouldn’t mind not getting back. Then you took yourself to the house of the local silversmith, where you placed the pieces under the table cloth. After a conversation about the weather, the crops, the neighbors, anything except the elf cross you wanted him to make for you, you shared some schnapps with the smith then changed places with him at the table. More chitchat ensued, with you listening very carefully when he talked about the state of his farmstead. Then you went home.

The exact procedure varied from province to province, but when a certain number of Thursdays had passed (Thursday nights being the most auspicious times for forging magical objects) you returned to the smith’s house, bearing a gift of whatever you thought was most needed on the farmstead. The earlier ritual was re-enacted, after which you found your finished elf cross waiting for you under the tablecloth.

It really was worth all that rigmarole. If you were ever pursued by elves, especially a dangerously amorous water elf like the one who abducted Sir Bosmer, the amulet might save your life. Attracted by the glint of silver, the elf would grab first at the amulet whose red string would then give way, causing the elf to fall back into its stream or lake and giving you time to run away.

No, the following craft does not require silver. Instead, we roll children’s modeling clay out thin like dough and cut shapes into it as we would a Pennsylvania Dutch cut-paper valentine or paper-thin Icelandic snowflake bread. Be sure to hang your elf cross on a red thread; any other color might not be as effective.

You will need:

1 four-inch square of white paper

Scissors

1 package black modeling clay (I like Crayola Model Magic)

Rolling pin or glass

Small, sharp knife

Strip of thin cardboard or cardstock

Silver metallic acrylic paint

Square-tipped paintbrush

Red string or embroidery thread

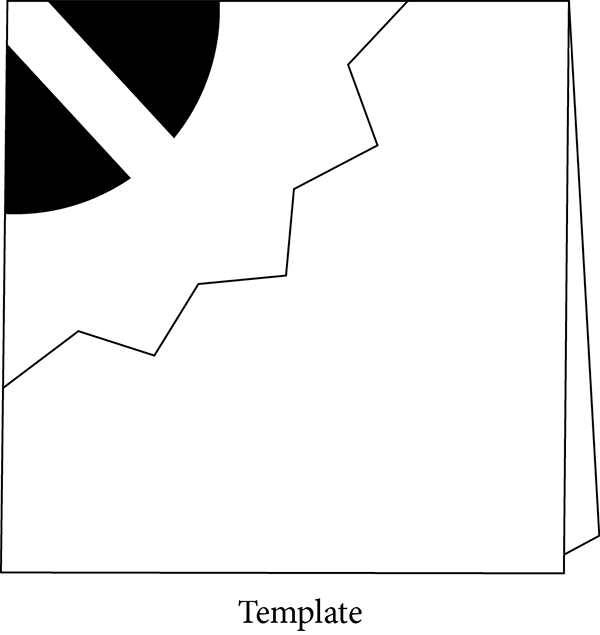

Fold your square of paper in quarters. Draw the design shown in the folded corner. Cut out and unfold. This is your template.

Roll out the modeling clay to about 3⁄8 inch thickness. Lay your template on top and cut around it with a sharp knife.

Use a very thin knitting needle and the end of a strip of cardboard to incise the dots and lines. Let dry overnight.

Using a very dry brush, paint your cross silver, letting plenty of the black modeling clay show through to give it a tarnished, antique look.

Hang your cross from a red thread.

SPELL BREAK: Knocking on Elfland’s Door

I have never been to Sweden, but if I ever do go, I’ll head straight for Halland on the Kattergat, the bit of sea that separates southwestern Sweden from Denmark’s Jutland and which the mound people’s sailless longboats were probably able to cross without much difficulty. When I get there, I’ll make tracks for Tvååker, where the folktale “Investigation of a Grotto” 50 takes place. Once I reach the town, I’ll be looking for a certain ridge, the north side of which is supposed to drop off into the above-mentioned grotto.

The word “grotto” puts me in mind of Circe and the turquoise waters of the Mediterranean. Why not just call it a cave? Cave, cavern, or grotto, the only way to explore this one is to lower the hardiest—or foolhardiest—of the local men down through the entrance by a rope. What were the villagers in the folktale hoping to find in there? It seems to me that whenever the practical Scandinavian peasant went poking into mounds or rock formations, he was looking for one of two things: building stones or treasure.

It would be very inconvenient to haul building stones up by rope one at a time, clutched in the arms of our stalwart spelunker, so we must assume they were looking for treasure. The cave was already known as the “troll’s parlor,” 51 which makes me think of polished woodwork glowing in the light of the hearth, a place to enjoy hot tea and seedcakes, not unlike a hobbit-hole. The resident troll was said to be one Hakon. In the Viking Age, Hakon was a name for kings and earls, so this would be a high-born troll and our local-on-a-rope (we’ll call him Sven) was probably expecting something a little grander than Bilbo Baggins’ sitting room.

While the Swedish troll was more or less the equivalent of an elf, the trolls had a special reputation for sitting on piles of treasure. In Småland to the east, they had a story about a little boy who was spirited into a mountain. The boy was eventually freed by the emergency tolling of the church bells, but not before he got a glimpse of the inside of the mountain. He reported that it had “gleamed,” 52 presumably with silver, for it was forevermore called Silver Mountain.

What Sven did find after he had crawled some way into the mountain outside Tvååker was an oversized iron door. It was locked from the inside, but Sven, no doubt scraped and bruised by now, was not ready to give up. He pounded his fists against the door, then pressed his ear against it to hear the startled residents of the mountain exchange muted words, probably something along the lines of “Who could that be?” and “Quiet! Pretend we’re not home!”

If Sven had gone on pounding, would the trolls eventually have opened the door? I’m afraid we’ll never know, for just then his antsy friends decided he had been down there too long and pulled him up again. After that, we are told, no one ever tried to explore the cave again.

If you have been to that cave in Tvååker since then and have found nothing of interest—no troll-made security door, no susurrations, no gleam of gold through the keyhole—then I would suggest you had arrived at the wrong time of year. Try again on Durin’s Day, or if that doesn’t fit with your plans, just wait until the moon shines down into the cave and touches the smooth arched stone you thought was not a door. With any luck, silver glyphs will appear on the surface just as they do at the entrance to the Mines of Moria in The Fellowship of the Ring. You should bring keys to both the elf and dwarf runes if you wish to read what was written there back in the days of Durin. Then all you have to do is “Say ‘Friend’ and enter.” 53

43. Tolkien, The Hobbit, p. 60.

44. Tolkien’s elves celebrated their New Year on April 6.

45. Tolkien, The Return of the King, p. 384.

46. Tolkien, The Hobbit, p. 60.

47. Tolkien, The Hobbit, p. 228.

48. Olrik, A Book of Danish Ballads, p. 22.

49. Sturluson, Heimskringla, p. 300.

50. Lindow, Swedish Legends and Folktales, p. 59.

51. Ibid.

52. Lindow, Swedish Legends and Folktales, p. 97.

53. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring, pp. 321–322.