Glory of

the Elves

W hen it comes to Christmas preparations, Scandinavians stick to a strict schedule. There are specific dates on which one must start the baking, soak the cod, repair last year’s tree ornaments, and cook the porridge for the resident nisse. If you lose track of the date, you’re lost. In Migratory Legend number 6030, which has many variants, a mortal has misplaced the calendar and wonders aloud how many days it is until Christmas. A helpful troll or hidden person overhears and gives the answer. And that’s how we know the elves celebrate Christmas too.

Before there was a Christmas, they would have celebrated the Viking Yule, and long before that they would already have been observing the winter solstice in a very big way. All these solstice-related activities would have occupied the mound people both while they still lived and long after they had repaired to their tombs to become elves. In the imaginations of the Old Norse poets, the elves had always been closely connected to the sun. Just as humans with elven ancestry were supposed to be more beautiful than ordinary mortals, full-blooded elves were said to be more beautiful than the sun. The Old Norse term álfröðull has been translated as “elf candle,” “elf beam” (as in sunbeam), and “elf glory.” It denotes the sun.

We know that offerings were made to the elves at cup-marked stones because it was still happening when churchmen, folklorists, and other concerned citizens started to write about such matters. Sun wheels almost always appear on cup-marked stones, and if there is a national flag of Elfland, it’s almost certainly emblazoned with a sun wheel. According to the Old Norse poem “Alvísmál,” the elves themselves referred to the sun as “the fair wheel.”

While the elves were never baptized into the new faith, they were celebrating Christmas by the Middle Ages, and they were doing so by dancing and moving about. Into the 1800s, they could still be depended on to take over the odd Icelandic farmhouse on Christmas Eve while the residents were at church. They’d push all the furniture against the walls to make room for swirling skirts and flying coattails as they danced across the floor. Some of these dances were wedding dances, but only if the elves could procure a mortal groom or bride—preferably one with a basket of rye bread in hand.

Humans, too, danced at Christmastime. The original purpose of the medieval Danish ballads quoted and discussed in this book was to provide accompaniment to the dance, especially at Yule when everyone gathered together in the warmth of the hall. The “burden” of each ballad was a line repeated between verses to signal a particular movement of the dance. If these had been line dances, we could probably dismiss the idea that they ever had anything to do with the cult of the sun, but they were danced with linked hands in a circle. Though it was no longer the case in the Christian era, they may once have been danced to encourage the sun to stick around a little longer each day after the winter solstice.

Jul is still the name for Christmas in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, Jól in Iceland.60 Like the modern English “Yule,” the words may mean “wheel.” The medieval and even nineteenth-century dancers often wheeled on out of the hall or farmhouse over the snow-crusted earth and down to the water. The docks were probably one of the foci of the mound people’s solstice ritual, for there they could enact the reappearance of the sun as it made its way out of the watery darkness of the underworld.

Fire, an indisputable element of sun worship, also had its place in the Yuletide dances. In the Swedish “judge’s dance,” a burning taper was passed from hand to hand, and the Icelandic “fairy dancers” of the early twentieth century wound their way down the rocky promontories on New Year’s Eve and Twelfth Night to light a bonfire in the town square with their torches. Round and round the fire they danced until the flames had consumed all. They were called fairy dancers not just because they danced the fairy dance but because they dressed as fairies too, half of them in white, half in black like the doomed Thidrandi’s dísir. The fairy king and queen who led the dance wore tinkling metal crowns, and if you ask me, they were just begging to be stolen by the hidden folk.

In Småland in southeastern Sweden, an “angel dance” took place after the Christmas Eve smorgasbord. I think it’s safe to say that these “angels” were once elves.

The longest night of the year was, in a way, the death of the sun. In the northern countries, death is very much on the mind at Christmastime. Graves are adorned with greens and candles, and not so long ago, ghost stories were told, visits expected from the ancestors, and there were all kinds of fortune-telling games to determine who was going to die in the coming year. Even on the dance floor, one could not escape the sense of doom. As they used to sing in the Færoe Islands, “Spare not your shoon, tread hard the floor; God alone knows if we meet at Yule once more.” 61

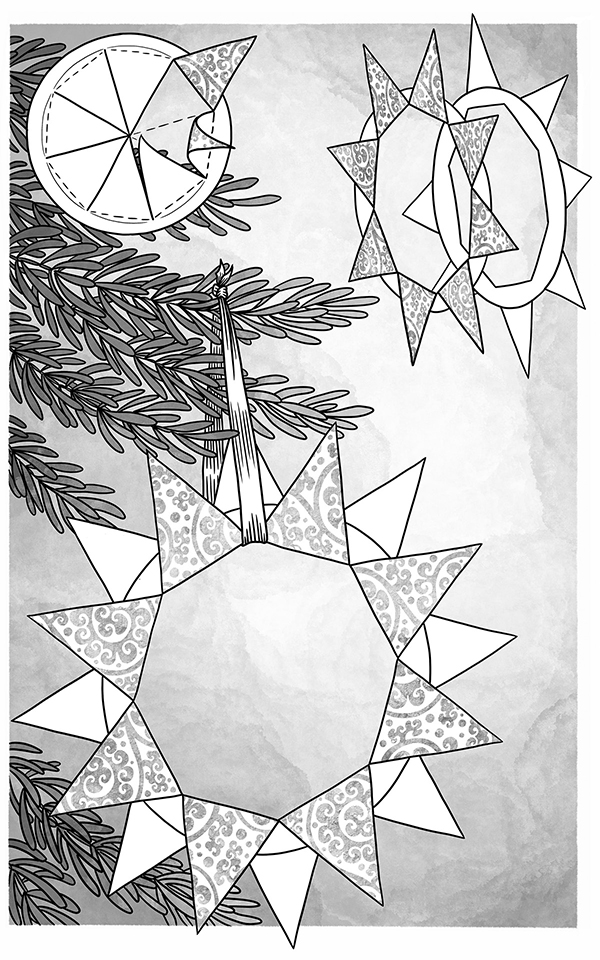

CRAFT: Álfröðull Ornament

The disk that’s pulled along on the Trundholm Chariot is only one of many golden sun ornaments that have been broken out of the soil of Sweden and Denmark. Some large, some small, most of them were cast in bronze then covered in gold foil and incised with concentric rings composed of spirals. Those that have no apparent purpose other than to be adored are simply “sun disks,” while spiked versions like those worn at the waists of Egtved Girl and Borum Eshøj Woman are called “tutuli” (singular, “tutulus”).

Several of the Danish oak coffins contained bowl-shaped mugs that probably held milk. The outside was decorated with a sun or star shape formed of little tin pins hammered into the wood. (Either way, it’s still a sun, for one elf’s sun is another elf’s star.) The following project is partially inspired by the form on the bottom of the cup from the Guldhøj mound. That star, too, has eight points positioned around an open circle, while the star at the center of the Balkåkra Sun Drum’s surface has the difficult and puzzling number of seventeen.

You can hang these stars on the tree individually or tie them onto a string to make a garland.

You will need:

Pencil

Nepali lokta paper (see CRAFT: Elven Pennons inChapter Six) or any paper that is printed on one side and solid on the other or a different solid color on each side, such as double-sided origami paper

Juice glass

Scissors

Glue

String or ribbon

Place the mouth of a juice glass on your paper and trace around it. Cut out the circle. Fold the circle you have made in half, then in quarters, then in eighths. Unfold. Place the slightly smaller bottom of the glass in the center of the circle and trace around it. Cut along each crease from the center to the edge of the inner circle to make eight “pie slices.” Fold each one up and out to make the point of a star. Glue each point down with just a dab of glue.

Repeat all steps to make a second star.

Glue the two stars back to back to make a sixteen-pointed star. Thread a string or ribbon through it and hang it on the tree.

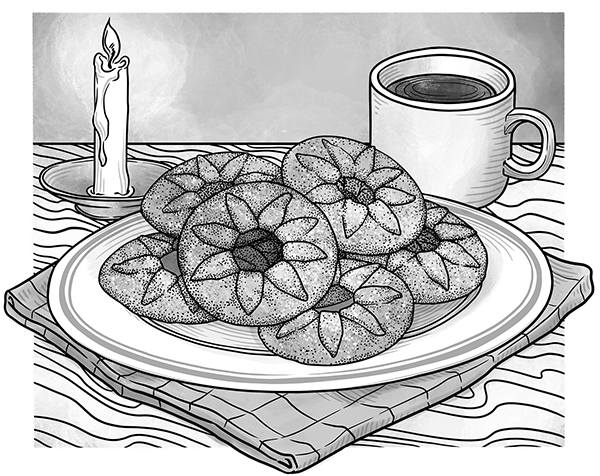

RECIPE: Álfröðull Cookies

To shape these cookies, we use the same technique as the paper Álfröðull ornament except that we make the inner circle smaller, and each cookie is just one layer, a star with eight points rather than sixteen. They look very pretty on a plate. I expect the “jolly old elf” himself would not be displeased to find them waiting for him by the fireplace on Christmas Eve. You can also string a ribbon through each one and hang them on the tree, but don’t forget to eat them before you take it down!

Ingredients:

¼ pound (1 stick) unsalted butter

¾ cup sugar

1 egg

1 tsp. vanilla extract

1 tsp. almond extract

A healthy dash of rum, whiskey, or whatever hard liquor you happen to have on hand

2 cups white flour, plus a little more for dusting

2 tsp. baking powder

2 tbsp. whole milk

You will also need:

1 large juice glass, mouth about 3 ¼ inches in diameter

1 shot glass or cup of similar size

Plastic wrap

Baking parchment

Sharp knife

Cream butter and sugar together. Beat in egg. Add extracts and rum. Add flour, mixed with baking powder, a little at a time, alternating with the milk as the dough stiffens. You will need to work it with your hands to get it thoroughly mixed. Shape into a smooth ball, wrap in plastic, and chill for half an hour.

Preheat oven to 400°F.

Roll out dough on floured surface to about 1⁄8 inch thickness. Cut out circles using the juice glass. Place circles on cookie sheet lined with baking parchment. Press the shot glass gently into the center of each circle, pressing just hard enough to make an impression. With a sharp knife, divide the space inside the circle into eight points. Carefully peel back each point and press down gently.

Bake for 10–13 minutes or until cookies are golden and points are lightly browned.

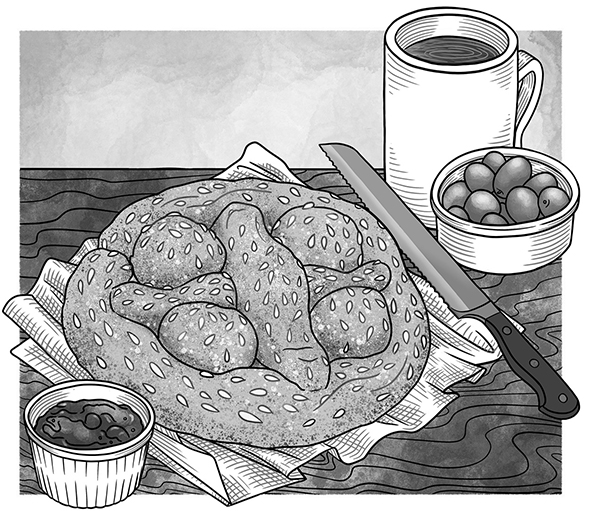

RECIPE: Christmas Rye Bread

There are several instances of nubile Scandinavian girls vanishing when they go to the storehouse to fetch bread on St. Lucy’s or Christmas Eve. The “bread” they would have been fetching is the ring-shaped crispy rye bread that hangs from a rod in the ceiling and that you can now buy in gaily wrapped packages at IKEA. Any other bread would have been eaten fresh from the oven. I’m guessing the elves grabbed the girl on her way out of the storehouse and that the bread may even have been their primary target.

While barley and wheat have been grown in Scandinavia since about 3000 BC and oats since 1000 BC, rye did not appear on the scene until the early Iron Age. At first, only a few families would have been growing it. Maybe they were Germans. The native farmers, intrigued by this new grain, would probably have tried to barter for some seed. If the rye-farming incomers had misunderstood them or been foolish enough to shut the door in their faces, the native farmers might have repaid them by snatching both girl and bread out of the farmyard under cover of darkness.

This recipe is for a fresh rye bread that’s baked specially for Christmas.62 The sun wheel shape is not traditional, but I’ll bet it once was back in Old Elfland.

Ingredients:

1 tablespoon butter, plus a little more for greasing

1 cup buttermilk

1⁄3 cup molasses

1⁄4 cup sugar

1 package active dry yeast

1 tablespoon orange zest

½ teaspoon aniseed

½ teaspoon caraway seed

1 teaspoon salt

1 cup light rye flour

1 ¾ cups white all-purpose flour plus a little more for dusting work space

1 egg yolk

Pearl sugar, if you can get it. Otherwise, white granulated sugar

9" cake pan, greased with butter

In a small pot, heat one tablespoon butter, buttermilk, molasses, and sugar until very warm but not scalding. Pour into a large bowl and stir in yeast until dissolved. Stir in orange zest, seeds and salt. Add flours a little at a time, mixing well first with a spoon, then with hands when dough stiffens. Shape dough into a smooth ball, place in a greased bowl, cover with a dishtowel and let rest in a warm place for fifteen minutes.

Dust counter or cutting board with flour. Turn dough ball out onto it and knead for about ten minutes. Return to bowl, cover with towel and let sit in warm place for about an hour, until dough has doubled. I like to poke two eyes and a round mouth into my dough: when the face has disappeared, I know my dough has doubled.

When dough has doubled, punch it down and turn it out onto the board. With a sharp knife, cut it in half. Roll one half into a long log. This is the outer ring of your sun wheel. Place it in the greased pan against the rim, but don’t press it into place. Cut the other half of dough in half again and roll it in into two logs. These are the “spokes” of your wheel. Place them crosswise in the pan, one over the other. Cut the rest of the dough into quarters and roll each one into a ball. Place them in the spaces. Cover and let rise another hour in a warm place.

Preheat oven to 350°F.

Brush top of dough with beaten egg and sprinkle with sugar.

Bake for 35–40 minutes. Let cool a few minutes, remove from pan and serve warm with butter.

SPELL BREAK: We Meet at Yule Once More

Nowadays, a quick swipe of the epithelial cells on the inside of your cheek can tell you how much Neanderthal DNA you might have, but there is as yet no test for elven blood. Still, one can dream, and I did. Several years ago I had one of those intriguing third-person dreams—you know, the ones where you’re not taking part in the action and the people in the dream don’t even know you’re there? In this one, such a test had in fact been developed and all those with elven blood were being encouraged to move to Iceland, which, in the context of the dream, seemed to be a stand-in for Elfland. Once they arrived, they were given full sovereignty along with modest homes, washers, and dryers. Unfortunately, I woke up before I could determine if this was supposed to be for the elves’ own protection or to remove them from normal human society.

You may never know your exact percentage of elven DNA, but trust me, it’s there. Earlier in this book, we saw how Sir Bosmer was withdrawn from the human gene pool by the lovelorn Elf-maid, but sometimes the genes flowed the other way. While the changeling rarely lives long enough to reproduce, adult elf women did occasionally make a point of injecting themselves into a royal line. They often didn’t stick around to mother their children but left them behind to rule and/or cause trouble.

Sir Bosmer’s Elf-maid came in the gloaming of a Midsummer’s Eve. Chapter 11 of The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki, which records the misadventures of an ancient Danish royal family, the Sköldungs, takes place a half turn of the year’s wheel later. King Helgi’s elf woman comes knocking on his bedroom door during the darkness of Yule. Tap tap tap. The weather outside is frightful, and Helgi wants to do the right thing, so he springs up to open the door even though, like Sir Bosmer, he isn’t expecting anyone. I’m sure Helgi wasn’t in the habit of answering his own front door (he was a king, after all), but this is the door of a small detached bedchamber inside the gate, and Helgi would have been confident that whoever it was had already been vetted by his housecarls.

But this visitor probably didn’t enter by the gate. The figure on Helgi’s doorstep is neither fair as the moon nor white as a candle, as one usually expects elf women to be. Instead, she is “poor and tattered,” 63 and not even recognizably female. To sleep with her is the last thing Helgi wants to do, but that’s exactly what she demands.

Helgi allows the stranger to creep under the covers but insists she keep her clothes on. As the loathly lady settles beside him on the straw mattress, she is transformed into a woman every bit as lovely as Sir Bosmer’s seductress. As she explains to the astonished Helgi, she has been traipsing all over Denmark trying to get into a king’s bed in order to break the ugly curse her stepmother cast over her. Curse broken, the beautiful elf woman is all for leaving now, but Helgi, predictably, is all for her staying the night.

The quickie wedding he suggests is obviously a euphemism—the saga was written down in Christian times when such out-of-wedlock dalliances were frowned upon. The elf woman conceives a child that very night, as she confides to Helgi in the morning. She instructs him to come and pick up the child down at the docks at the same time next year. Here we have the familiar Christmas recurrence that is preserved in the later folktales in which girls disappear one Christmas Eve to reappear briefly at the next.

But deadbeat dad Helgi flounts both the tradition and the elf woman’s instructions, and two more Yules go by without his claiming or even looking for the child. On the third, three women ride up and set a little girl down in front of his hall. The little girl had been named Skuld, “that which will be paid,” after one of the three norns. Are these mounted women norns themselves? Skuld’s mother was identified only as “an elfin woman,” 64 but she could be one of those norns who are also elves.

In keeping with her nornish calling, Skuld’s mother speaks a prophecy: Helgi will reap some rewards for having freed her from her stepmother’s curse, but he’ll also pay for having ignored her instructions. Helgi does indeed score some victories before he is cut down by a treacherous son-in-law.

Little Skuld, who stays on in her father’s hall, turns out to be a handful. She grows up to become a “powerful sorceress,” 65 but whether her powers are the result of her elven blood or the study of her craft, we do not know. She was probably beautiful too, since those with elven blood were supposed to be better-looking than ordinary people. She marries the powerful King Hjorvard, then belittles him because he is not as powerful as her half-brother Hrolf. Unable to bear Hrolf’s and her husband’s unequal standing, she assembles an army worthy of Narnia’s White Witch,66 calling forth “elves, norns and countless other vile creatures,” 67 even draugs, to do battle with King Hrolf. Predictably, the fighting takes place on the frozen moor at Yuletide.

This story contains just about all of elfkind except dwarves, but they, too, are distantly represented. The slain hero Hrolf is buried with his sword Skofnung, “the best sword ever carried in the northern lands,” 68 a blade that rang with a musical note whenever it hit bone. So precious is Skofnung that it’s stolen out of the mound a few hundred years later by an emigrant on his way to Iceland. There, the poet Kormak gets to wave it around a bit before it makes its way home again to Denmark. Such a remarkable sword could only have been forged by dwarves.

But the pertinent question is whether or not the half-elven Skuld had any children. I think she must have. Elves were instruments of fertility, after all. Just by handing over an apple, as a very dís-like “wish maid” does in The Saga of the Volsungs, an elf could jumpstart a couple’s baby-making powers. During the final battle with Hrolf, Skuld commands a spectral boar, a totem of the fertility god Frey. The tusked boar was also a popular helmet crest among ancient Germanic warriors. Frey, however, was never a war god. The boar was probably his symbol because wild sows had so many little striped piglets. So no, I can’t imagine Skuld was barren.

The reason her children are not mentioned in the saga is probably because they and their descendants were wise enough to lie low after Skuld suffered her own inevitable downfall. An elf in the family tree was something to crow about, but Skuld was also a witch.

According to the lab technicians at Geno 2.0, 19 percent of my DNA is of Scandinavian origin. Since both sides of my family have been traipsing back and forth across northern Germany for as long as oral history and church records can remember, it’s likely that most or all of these genes passed first through Skuld’s Denmark, maybe even through Skuld herself. If she ever actually existed, I’m hoping Skuld wasn’t as bad as the saga makes her out to be. The author’s Christian stance is clear, so he would naturally be biased against a half-elven sorceress. If we could hear the story recited by a tenth-century pagan scop, we might get a very different picture of King Helgi’s illegitimate daughter. Then again, it’s not as if there were no evil witches or wizards back in pagan days, so maybe she really was as bad as all that. Either way, I’ll continue to look out for an official letter promising me a free two-bedroom house with washer and dryer in Elfand.

60. In Finnish, a non-Germanic language, it’s Joulua, a loan word from the Finns’ Germanic-speaking neighbors.

61. Olrik, A Book of Danish Ballads, p. 6.

62. There is a recipe for the crispy kind on pages 116–117 of my book Night of the Witches.

63. Byock, The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki, p. 22.

64. Byock, The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki, p. 23.

65. Byock, The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki, p. 70.

66. There’s no question that Tolkien did read The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki, but did C. S. Lewis? The similarities between Skuld and the White Witch are so striking that I’m guessing J.R.R. recommended the saga to C. S. one Thursday evening in Magdalene College when the Inklings gathered to discuss their work.

67. Byock, The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki, p. 71.

68. Byock, The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki, p. 68.