Stendhal ends a very brief start at an autobiography, written in 1831, with the words ‘I was born in Grenoble on 23 January 1783 [. . .]’ (OI, II, p. 971). Perhaps discouraged by the pedantic accuracy of this date, he promptly gives up on the notion of completing either this sentence or the story of his life – none of his autobiographies are finished in any conventional sense, although the others are admittedly all considerably more developed than this one. The ‘I’ is in any case misleading: Stendhal rarely wrote in his own name except administratively, perhaps in some small part because his own name was not in fact his own, but rather that of his elder brother, the first Henri Beyle, who had been born almost exactly a year earlier, on 16 January 1782, only to die a few difficult days of life later. No doubt the second Henri Beyle was both conceived and conceived of as a consolation to his still grieving parents. From an early age, however, he appears to have become adept at frustrating their expectations, at least if the account of Stendhal, or rather Henry Brulard, his (pseudo-)autobiographical avatar, is to be believed – there may in fact be little reason to believe either of them.

Stendhal appears to have identified with the name Henri – he was in fact christened Marie-Henri – but seems to have preferred it in its foreign versions: the English Henry of the Vie de Henry Brulard and the Italian forms, Arrigo and Enrico, which he used in two projected epitaphs for his imagined tombstone. It was important to him to rewrite his first name: to customize it by stretching it to encompass all the many people and nationalities he had become by dint of living, writing and loving, the three activities by which he further defines himself in the epitaphs.

Stendhal appears to have been less fond of his surname, as indicated by his obsessive use of pseudonyms. As far as we can tell, his main objection to the name Beyle – pronounced and sometimes wrongly transcribed as ‘Belle’ – was to its status as a patronym. From an early age, Henry Brulard claims he equated paternity with tyranny, which is perhaps in part why Henri Beyle never went on to have children of his own. He likewise considered the institution of marriage to function as a male tyranny over women, which is perhaps why he never went on to marry – although he did propose to a sequence of women, interestingly none of whom he loved as much as the women to whom he did not propose and all of whom very sensibly turned him down. Brulard concludes that it was probably just as well that he had never been accepted, noting that ‘happiness for me is to give no orders to anyone and to take none in my turn’ (OI, II, p. 948) – that is, happiness is finally freedom, even more than it is love. If Henry Brulard lists love as ‘always my chief, or rather my only preoccupation’ (OI, II, p. 767), it is because, as a Romantic, he hoped one day to find a love that might, however improbably, take the form of a perfect coincidence of two freedoms.

Oddly, Stendhal never switched to the matronym Gagnon, associated with his beloved mother Henriette, his beloved maternal grandfather Henri and his beloved maternal great-aunt Élisabeth. Instead, he generated hundreds of often extremely silly pseudonyms: estimates vary between 170 and 350. He eventually settled on (Baron Frédéric de) Stendhal as his principal, but by no means exclusive, pen name and Dominique – after Domenico Cimarosa, the composer of his favourite opera, Il matrimonio segreto (The Clandestine Marriage, 1792) – as his pet name for himself.

Stendhal’s choice of pen name may have been intended as a nod in the direction of the writer Mme de Staël, traditionally pronounced ‘Stahl’ – we think we know that Stendhal ought to be pronounced to rhyme not only with ‘Stahl’ but with the French word scandale, on the strength of his occasional use of the verb stendhaliser as a pun on scandaliser, although there is in fact some dispute about how scandaliser was pronounced in the first half of the nineteenth century, so actually we don’t really know at all.

The name appears to have been derived from that of Stendal, a town in Brandenburg: the totemic ‘h’ for Henri/Henry may have been inserted also to make the name appear more barbarously Teutonic. As we shall see, Stendhal spent part of the Napoleonic period as an administrator in Germany, and perhaps he chose to adopt the name of a place he had passed through for personal reasons that are now mysterious. Or he may have been attracted to the name of the town on account of its having been the birthplace of the art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann.

Stendhal may have been particularly drawn to Winckelmann by the latter’s murder in Italy (Stendhal was always very interested in murders) or status as Europe’s foremost expert on art (Stendhal was, by then, trying to launch himself as an expert on Italian painting) or homosexuality, as evidence of his singularity. Stendhal may even obliquely have been signalling his own (latent? active?) bisexuality: his friend Prosper Mérimée reports that Stendhal used to insist that all the great men of history were attracted to their own sex, citing Jesus Christ and Napoleon as examples (HB, p. 446).

It is not clear whether Stendhal ever really considered himself to be a great man – in this respect, he appears more modest than Balzac, who likewise associated homosexuality with superior singularity, most notably in the recurring character of Vautrin, and for whom his own greatness was never in any serious doubt. It is similarly not clear whether Stendhal was sexually drawn to men, although on occasion he does record himself to have been captivated by male beauty. What does seem certain is that he found the idea of both male and female homosexuality at once unsurprising and charming; that many of his friendships were intense, including some with men; and that he experienced friendship – the giving and receiving of esteem – as a form of love. We shall never know if Stendhal ever slept with a man, although the balance of probabilities is that he didn’t, any more than we shall ever know whether, in Armance, Octave de Malivert is gay, sexually impotent, mad or a Romantic. Possibly Octave is latently or intermittently or indeterminately all of those things; possibly Stendhal was too. To think one has found something out about Stendhal or one of his fictional characters is typically to miss lots of other things entirely.

The artist formerly known as Marie-Henri Beyle produced an endless series of false identities, some of which he wrote about and have therefore been preserved. He appears to have had the thought that these multiple selves might successively, cumulatively and contradictorily reflect – and ultimately even constitute – his real self, increasingly divergent from the self he was born to inhabit: the self that was to have been determined by parental expectations, already formed around his dead namesake elder brother, and by his inherited identity as a middle-class provincial Frenchman.

Stendhal ought really to have stayed all his life in Grenoble and become a lawyer, following in the footsteps of his father, Chérubin Beyle, who had in fact inherited his office at a relatively young age from his own lawyer father. The French Revolution appears to have encouraged Stendhal in the thought that his life could depart radically from these and other expectations, for he conceived of the Revolution as an enabler of radical personal freedom, including his cherished freedoms to redefine and reinvent himself – hence his endless choices not just of new names and personae, but of new and changing civic and national identities.

If Stendhal used his imagination to write, unwrite and rewrite an ever-changing set of selves, it was in order the better to tend towards his real self. Curiously, however, the move away from his origins brought him full circle back to his patronym. The name Beyle resurfaces in beylisme, a word Stendhal coined in 1811 to describe his practice of defending his real self against normative external attack, most notably by rejecting the false ideas of conventional morality; it resurfaces again in the epitaphs Stendhal composed for his tombstone, in which he appears as Arrigo Beyle and Enrico Beyle. Thus at those moments when he sought most rigorously to account for what he truly was, and what he truly had been, Stendhal appears to have accepted that he was still in part the product of his patriarchal family.

There is always a tension in Stendhal between things as he would like them to be and things as they are, between the ideal and the real. The truth, at any given point in time, is probably a combination of the two, for we are always more than what we rationally appear to be, in Stendhal’s case, more than simply Henri Beyle from Grenoble, but less than what we would imaginatively wish to be – less than Arrigo Beyle from Milan.

All this talk of ‘real’ selves must sound terribly naive – happily, Stendhal is always at least one step ahead. At the centre of each of us, Stendhal gives every impression of thinking, is a void around which orbit acquired fragments of personality. His two main autobiographical projects turn around the questions of what kind of person he might have been and what value that person might have possessed – what the orbiting fragments add up to, if anything. Lucien Leuwen likewise asks himself, and finally others – his father, a friend – whether he has any value. But Stendhal understood that asking other people was typically of little use, for we are likely to be perceived very differently by each of the friends, acquaintances or enemies who come to behold us. Even more radically, Stendhal came to understand that this ‘real’ self was in fact particularly unknowable to himself. As Henry Brulard puts it, ‘what eye can see itself?’ (VHB, II, p. 535). So should we just give up trying to know ourselves? No: Stendhal found two answers to his problem. The people we most esteem are those who can most be trusted to know us and indeed to tell us what our true value might be – hence the fear they inspire. Also, we are the sum of our performances of ourselves. This idea of performance as the closest we might be able to come to representing ourselves accurately, or our fictions of the self as the closest we might be able to come to the truth of ourselves, is part of what helps us to make sense not just of Stendhal but also of such intensely histrionic heroines as Mina de Vanghel, Vanina Vanini, Mathilde de La Mole and Lamiel – the freest, most beyliste and therefore, in some important ways, most appealing of his fictional characters. In the modern world emerging after the definitive fall of Napoleon in 1815, Stendhal tells us that people – especially men and even more especially French men – take themselves far too seriously: they conform to a socially imposed idea of their own dignity and live in fear of giving rise to ridicule by departing from the expectations that surround and define their socially allotted roles. Yet, for Stendhal, it is our refusal to meet such expectations that alone gives expression to the self. It is for this reason that we should find our escape by playing inappropriate roles or, even better, by appropriating roles inappropriately. It is when we seem least the person we ought to be that we are in fact most ourselves – not so much our ‘real’ selves as our singular selves, that is to say our own creations. As Gide once again suggestively puts it when defining what he refers to as the ‘inverted sincerity (of the artist)’,

He ought not to tell the story of the life he has lived but rather to live the story of the life he will write. Put another way, let the self-portrait that is his life conform to the ideal self-portrait he would wish to see; or, put more simply still: let him be as he wants himself to be.1

Stendhal’s surviving correspondence gives a strong indication that a number of his friends did indeed learn to understand and appreciate him, making sense of his inappropriateness by laughing as opposed to taking offence. Unfortunately, the principal extended account of Stendhal written by a friend, H. B. (1850) by Mérimée, although rich in suggestive anecdotes, chooses to stress the inconsistency of its subject’s character and the changeability of his opinions as though such flightiness were a bad thing. If we are to judge by Le Rouge et le Noir, Stendhal particularly valued the unintelligibility and unpredictability of others: what he terms their singularity. Likewise, Henri Beyle valued his own unintelligibility and unpredictability, both to himself and to the people who nominally knew him best. H. B. in fact tells us more about Mérimée, and about how Henri Beyle played up to and parodied his friend’s idea of him – for Stendhal was a staggeringly perceptive man who made a lot of jokes simply for his own amusement – than it tells us about its ostensible subject. In order to make sense of Stendhal, we need to generously acknowledge his inconsistency not as something to be resolved but rather to be enjoyed. In other words, we need to recognize what John Keats, quite separately from Stendhal and unbeknownst to him, refers to as negative capability – ‘that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason’.2

Looking back at his childhood, Henry Brulard irritably reaches after fact and reason, even as Stendhal remains aware that everything is mystery and doubt. The story concocted by Henry is unnaturally consistent, partial and unfair. It positions him between two families: the real family made up of the various extant Beyles and Gagnons, and the ideal family that was the French Republic. In the process, it provides him with two imagined identities: Henry the downtrodden slave and Henry the precocious freedom fighter. Yet much is also revealed that does not fit either of these narratives – it is possible his family circumstances were not quite as grimly conflictual as he said they were.

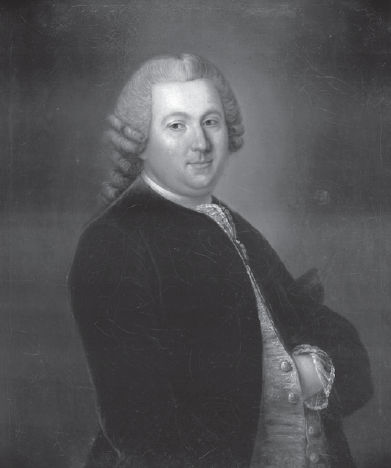

Anonymous artist, Dr Henri Gagnon, 18th century, oil painting.

Stendhal’s early childhood was almost certainly unremarkable. He appears to have loved his mother a great deal and clung to her: Henry observes that, still a small child, he loved her the way he would one day love Alberthe de Rubempré – of whom more later – and that he would have wanted to kiss her body all over, there being no clothes to come between them (OI, II, p. 556); he also fairly clearly wanted his father – to whom, in later years, he would habitually refer to as ‘the Bastard’ – dead. Henri may have been largely unembarrassed by his infant sexuality, his mother possibly less so. That said, there is no sense of her having either encouraged or, in any hurtful way, rejected him, and probably she doted on him, despite or perhaps particularly because he passed for a relatively ugly and uningratiating child.

Henriette is described by Brulard as beautiful, graceful like a doe, kind and cultured: she even spoke Italian, reading Dante in the original. He concedes that she might have been a bit too short, but otherwise can think of no flaws in her. In particular, Brulard comes to the conclusion that she displayed two notable moral qualities: ‘Henriette Gagnon was possessed of a generous and headstrong nature; I worked this out in retrospect’ (OI, II, p. 973). Her husband – the withered, careworn and in no way cherubic Chérubin – had made something of his career as a lawyer and prospered, owning an apartment in Grenoble and a small country residence in the nearby village of Claix. Just around the corner from the Beyles, overlooking Place Grenette, one of Grenoble’s main squares, lived Henri Gagnon, Henriette’s doctor father.

He had once been on a pilgrimage to visit Voltaire in Ferney, as commemorated by his proud ownership of a bust of the great man, and had been part of the delegation that had welcomed Rousseau at the gates of Grenoble when the latter came to visit the city in 1768: unsurprisingly, Dr Gagnon possessed a certain social standing, both before and during the Revolution. As befitted a man of his status, he wore a powdered wig.

He appears to have been a kindly man, indulgent to his extended family, eager, whenever possible, to avoid conflict, including by sometimes (not) shielding his grandson from the consequences of his own behaviour. In his professional life, he showed himself willing to administer not only to the wealthy but to the poor, sometimes even pro bono. Dr Gagnon’s sister, Élisabeth, appears, by contrast, to have possessed inflexible moral courage and, consequently, to have been quite difficult. In particular, Élisabeth had a code of honour, grandly associated both by her and by Henry with the values immortalized in Pierre Corneille’s Le Cid (1637), to which she adhered, at whatever personal or human cost. Élisabeth was the first of many difficult women whom Stendhal would come to adore – it’s possible women aren’t ‘difficult’, but instead more likely, in a patriarchy, jealously to guard their autonomy. Henry Brulard tells us that Dr Gagnon ‘esteemed and feared his sister’ (OI, II, p. 591).

Dr Gagnon’s flat, now the Musée Stendhal, was larger than that of Chérubin Beyle, lighter and more airy, as well as possessed of a terrace adorned by a trellis. It lay between Place Grenette and the public gardens, and was therefore much better situated than the parental home. Throughout his childhood, Stendhal unsurprisingly liked playing and studying there rather than in his father’s flat, also because he preferred the society of his mother’s family, with one exception: his aunt Séraphie. Henri came to detest his mother’s sister, just as he came to detest his own sister Zénaïde – he (thought he) adored his other sister Pauline; another sister, Marie-Caroline, had died in infancy. His very strong reaction against Séraphie is no doubt connected to the event that, in Brulard’s account, marked the start of Henry’s moral life, shaping his sense of self evermore. When he was only seven, on 23 November 1790, Henriette died in childbirth, allegedly with Henry’s name on her lips (OI, II, p. 973). In a curious note designed to confuse the police, Stendhal identifies himself as the widower of Charlotte Corday, another of his Revolutionary heroines (OI, II, p. 961): certainly Henry came to adore Charlotte, a difficult woman if ever there was one, but the note carries the trace of another, earlier bereavement. All his life after the age of seven, one of Stendhal’s many identities was that of his mother’s widower.

Photograph of the trellis at the side of Dr Gagnon’s flat, seen from the public gardens, late 19th–early 20th century.

From the young Stendhal’s perspective, Henriette had presumably been murdered by her husband twice over: first, he had, unspeakably, once again impregnated her; second, to deliver her of their importunate child, he had stupidly hired an incompetent doctor, instead of the competent doctor who would doubtless have saved her. Brulard, writing past the age of fifty, eventually concedes that his father was overcome by grief at the death of his wife, and that the marks of this grief went largely unrecognized by the young Henry: ‘[My mother’s] room was left locked for ten years after her death . . . Now that I think of it, this sentiment on the part of my father does him a great deal of credit in my eyes’ (OI, II, pp. 557–8). Put more characteristically and on the face of it less charitably: ‘My father, who adored his wife all the more because she did not love him, was made stupid by grief. This state lasted five or six years; he started to pull himself out of it by studying chemistry first in Macquer, then in Fourcroy’ (OI, II, pp. 973–4).

Note to the police, written in Stendhal’s hand, identifying the author of the Vie de Henry Brulard as Charlotte Corday’s widower.

Actually, nothing could be more movingly Stendhalian than to love a woman who does not return that love and to pull oneself out of the resulting state of emotional prostration by developing an abstract passion for chemistry. The Vie de Henry Brulard tells us that Henriette died at the age of either 28 or thirty (OI, II, p. 556); in fact, she died at 33 (OI, II, p. 973). Numbers mattered to Stendhal, and Henry’s miscalculation is no error: what he’s saying is what he goes on to say explicitly, namely that his mother died ‘in the flower of her youth and beauty’ (OI, II, p. 556); what he is also saying is that she died at the age Stendhal associated with Métilde Dembowski, also of whom more later. In De l’Amour, Stendhal argues that young women of eighteen – the women he would go on to write about with such evident admiration in his fictions, most notably Mathilde de La Mole and Lamiel – eventually turn 28. They grow up even as they are still young, suddenly becoming capable of passion (DA, p. 75). Put another way, the self-assertion and the pride and the impatience he so values – his mother’s quality of decisiveness – come to be tempered by generosity. Something of this process is captured in Le Rouge et le Noir by Mathilde’s development from metaphorical princess to metaphorical queen.

Rousseau tells us in Les Confessions – a self-conscious model for the Vie de Henry Brulard, just as both Les Confessions and Vie de Henry Brulard becamse self-conscious models for Gide’s Si le grain ne meurt (If It Die, 1926) – that he eventually embarked on an affair with an older woman, his aristocratic patroness, Mme de Warens. Artlessly, he tells us that his private name for her was ‘Maman’. Similarly, Stendhal invests his two most developed ‘angelic’, as opposed to ‘Amazonian’ female characters, Louise de Rênal in Le Rouge et le Noir and Bathilde de Chasteller in Lucien Leuwen, with an almost limitless materno-erotic charge. The two categories of ‘angelic’ and ‘Amazonian’ female protagonists were first proposed by Jean Prévost, probably the most Stendhalian of Stendhal specialists, finding his death as he did in 1944, fighting for the French Resistance in Sassenage, a village near Grenoble that Stendhal knew well. Both Louise and Bathilde are 28, and their stories come to be dominated by their (possible) status as mothers. For his part Rousseau had of course never known his mother: she was a figure of fantasy, intimately bound up with his guilt at having killed her. Stendhal, on the other hand, knew his mother and gave himself over to the pleasure of finding her again in his fictions.

Anonymous artist, Caroline-Zénaïde Beyle, 19th century, oil painting.

Anonymous artist, Pauline Beyle, 19th century, oil painting.

All that said, what Stendhal most wanted was a sister. To recap, he ended up with two of them, his third having died in infancy. We shall never know whether Zénaïde was indeed the ghastly tell-tale he made out, but we do know that Pauline was both the sister he had always wanted, and not.

His side of the extensive correspondence between them has, to a large extent, survived: Henri was a very attentive brother, one might even say overbearing. From the outset, he wished her to be free and unconventional. He also saw that, as a woman in the nineteenth century, for her to have chosen such a life would have been to expose herself to great risk. The strategy he therefore advocated was one of public compliance and personal freedom. He appears to have hoped that Pauline would become not unlike Louise de Rênal, detached from her eventual husband by her inalienable pride as a free human being. Pauline duly married François Périer-Lagrange, like M. de Rênal a dull provincial obsessed with his estates, on 25 May 1808. When this husband eventually died, Pauline came briefly to live with her ostensibly loving brother, as he recalls in the Souvenirs d’égotisme (Memoirs of an Egotist), composed in 1832:

I was severely punished for advising one of my sisters to come to Milan with me in 1816, I believe [in 1817]. Mme Périer attached herself to me like an oyster, charging me with everlasting responsibility for her fate. Mme Périer possessed all the virtues, as well as a fair quantity of reason and charm. I was obliged to quarrel with her in order to rid myself of this oyster, maddeningly attached to the hull of my vessel, who, whether I liked it or not, held me responsible for all her future happiness. The horror of it! (OI, II, p. 488)

He had dutifully written for years with unsolicited advice. What more could now be expected from him? I think it is possible that Stendhal was, finally, a not very good brother to Pauline.

It is hard to make sense of the devastation produced by the loss of his mother simply by reading Brulard’s analysis of it, for this employs some of the rhetoric found in Rousseau’s account of the death of his mother in Les Confessions (1781–8). One way to make sense of oneself, as far as both Stendhal and, after him, Gide are concerned, is to identify with the story of another. Stepping back from Brulard’s own representation of the event, however, we can quite clearly see its consequences in the account of his subsequent childhood.

Henry withdrew from his family and from other children; he quickly became, and long remained, extremely angry, especially at his father, but also at his aunt, who somehow failed to understand that he had been too devastated to show overt grief: ‘I had been unable to cry after the death of my mother. I only started being able to do so more than a year later, alone, at night, in my bed’ (OI, II, p. 676). Hence, no doubt, her cruelty to him in the immediate aftermath:

When I entered the drawing room and saw the coffin draped in black cloth which contained my mother, I was seized by the most violent despair: finally I understood what death was. My aunt Séraphie had already accused me of not caring. (OI, II, p. 567)

An unfortunate intervention by the Abbé Rey, a family friend attempting to console the grief-stricken Chérubin, had the effect of making Henry extremely angry also at Providence: ‘“My friend, this comes from God”, he eventually said; this phrase, spoken by a man I hated to another I couldn’t stand, gave me a great deal to ponder.’ (OI, II, p. 564) ‘God’s only excuse is that he doesn’t exist’ became one of Stendhal’s favourite dicta according to Mérimée (HB, p. 445) – Nietzsche would eventually ask himself whether he might not in fact be ‘envious of Stendhal’ for taking away from him ‘the best atheistical joke that precisely I might have made’.3

Another of Stendhal’s identities was therefore that of the anti-clerical atheist, although he came to like a number of perfectly estimable priests and to find sincere religious faith rather touching, not least because it struck him as evidently mad and therefore singular. More generally, Stendhal appears to have thought of madness as an exception to the prevailing hypocrisy typically encouraged by (Jesuitical) Catholicism, understanding it as a pressing need for sincere utterance, likely to make us appear ridiculous and to isolate us, but also capable of suddenly opening up unexpected paths to all-too-rare direct and urgent communication. It is possible that Stendhal was sometimes guilty of producing communication that was both too direct and too urgent, even for the tastes of the people he most esteemed.

To return to the impact of his mother’s death, Henry went overnight from being a happy child to an unhappy child, and someone had to be held responsible for this numbingly awful change. It has been argued that Henry’s anger reveals that he in fact considered himself to be to blame, on some level, for Henriette’s death, having resented the impending arrival of a sibling and hoped that the birth would go wrong in some way.4 Maybe. But what’s perhaps more important is that Henry himself identified his moral life as starting not in fact with the death of his mother, but with the uncontrollable anger to which her sudden death gave rise.

Throughout his life, Stendhal arrived at distinctive moral positions that struck many people as immoral due to being unconventional, needlessly provocative or even pitiless. Each of these derived from intense surges of anger provoked by the endless spectacle of human injustice. Henry would frequently come to be identified as ‘atrocious’, an epithet first applied to him by his aunt Séraphie; he in fact claims the label as a badge of honour, we might even say as another identity. For to pass for atrocious in the age of cant is to refuse the atrocity of an unjust world. It is possible we should all be a lot more angry; equally, Stendhal argues we should all learn to laugh more at events we can’t control, avoiding what he refers to as impotent hatred. Stendhal spent most of his adult life keeping these two contradictory thoughts in his head, as ever unresolved.

The new Henry, mere days into his moral life, started to think of himself as different to those around him: misunderstood, nobler, finer in feeling. Quickly, Henry became a heroic figure in his own mind: atrocious, ferocious, intransigent. This intransigence belonged at once to another age – the time of the ancients described by Plutarch in the Parallel Lives – and to the new age of Revolution. A further Stendhalian identity is therefore Greek and Roman: Henry as the heir to Dion, Timoleon and Marcus Brutus, Plutarch’s fearless tyrannicides; or, in new money, Henry as Charlotte Corday’s widower, for she had stabbed Marat in his bath under the influence of Plutarch’s heroes, feverishly thumbing through her copy of the Parallel Lives the day before the assassination.

Élisabeth Gagnon cannot have helped her great-nephew recover from these delusions: stern, inflexible, she provided a constant reminder that one could indeed cut an isolated, heroic figure more or less indefinitely. She further encouraged Henry to start to assume yet another of his lasting identities: perhaps also remembering his mother’s facility with the Italian language, and its happy musicality, Henry began to imagine himself descended not from the local peasantry but from glamorous Italians. Élisabeth’s tales of her forebears led him to decide that the Gagnons hailed originally from Rome: in the sixteenth century, one of Stendhal’s two favourite periods of history, the other being the extended parenthesis in his own life provided by the French Republic and Empire, a certain Guadagni or Guadaniamo murdered someone in Rome and fled the city for Papal Avignon. In reality, the entire fantasy rests only on the Gagnons having found their way to Grenoble from Provence. For Freud, such reimaginings of one’s antecedents betray the neurosis associated with his concept of the ‘family romance’;5 for Stendhal, they exemplify a drive for happiness, that is, freedom.

Stendhal’s epitaphs for himself define him retrospectively neither as Grenoblois (perish the thought), nor as Parisian (even though most successful French men and women eventually come to identify themselves as Parisian), nor even as Roman (despite his alleged ancestor the assassin), but instead as Milanese. Even though Stendhal’s German pseudonym has come to stand in for Henri Beyle’s real name in the eyes of his readers, in his own eyes his life was in fact that of a Franco-Italian hybrid: Arrigo Beyle, milanese. The hybridity is often neglected: it is easy to assume that, by proclaiming himself Milanese, Stendhal is electing an exclusively Italian identity. But this is to forget that, even as Stendhal privileged his Italian (and German) imagination, so he remained stubbornly attached to what he considered to be his French logic: ‘la lo—gique’ is how Mérimée tells us he pronounced the word, with a marked interval between the syllables for extra emphasis (HB, p. 445). As we shall see, from his childhood onwards, Henri Beyle adored mathematics, thinking of it as exempt from hypocrisy: as a pure expression of truth in an age of cant defined by lies. Over the course of his life, he developed a list of other things exempt from hypocrisy: rote memory, physical courage, winning a battle as a general, making someone laugh in conversation – you cannot pretend to be funny; you either are or you aren’t. But mathematics always functioned as the touchstone for Stendhal’s version of logic, just as opera and other vocal music, even more than literature, always functioned as the touchstone for his version of imagination. Nevertheless, we can also say that Stendhal developed a general interest in another manifestation of logic, namely philosophy, not in its ‘mystical’ German forms – in reality, he was dismissive of German philosophy for the excellent reason that he had read barely any – but in its French post-Enlightenment guise of Ideology, defined by Stendhal as the dispassionate study of how we arrive at our ideas. One of the leading lights of this movement, Antoine-Louis-Claude Destutt de Tracy, comte de Tracy, was to become Stendhal’s somewhat boggled friend in 1817, having long already been his teacher thanks to his published writings, most notably the seventeen volumes of his Éléments d’idéologie (Elements of Ideology, 1802–15).

Destutt, and then eventually the moral squalor of post-1815 France, disposed Stendhal to try to see what Voltaire terms ‘things as they are’ – in L’Ingénu (1767), Voltaire describes his hero very much the way Stendhal liked to see himself: ‘He saw things as they are, whereas the ideas we are given in our childhood make us spend all of our lives seeing things as they are not.’6 Italy, by contrast, served as the land of beauty and imagination, a stage set for opera, showing us glimpses of things as one would wish them to be – lies. Lurking within Stendhal, from his childhood onwards, was this tension, between Voltaire and Rousseau, mathematics and fiction, logic and imagination, truth and lies, Henri/Henry and Arrigo/Enrico. It was a tension that Stendhal chose to leave unresolved. He wanted many names for himself, and many identities, the better to live in the gaps between each of these, so as to be happy, so as to be free.

André Louis Victor Texier (1777–1864), after Charles Toussaint Labadye (1771–1798), Antoine Destutt de Tracy, c. 1789, line engraving.