Brulard’s slavery to his birth family had been made inexpressibly worse by what Henry portentously refers to as the ‘Raillane tyranny’ (OI, II, p. 604), for in his bid to prevent Henry from playing with common children, Chérubin entrusted him to the care of tutors. The first of these, a certain Joubert, wasn’t up to much before helpfully dying. His dreary replacement was Jean-François Raillane, a Jesuit in the fullest sense, seen by Henry as a filthy and morally and physically repulsive hypocrite. The aim of the education Raillane provided was to reinforce the aristocratic values of Brulard’s family – its misguided sense of its own dignity – and to pervert the idealism of his young charge. It also tended to treat truth as both in and of itself suspect and an irrelevance:

One day, my grandfather said to the Abbé Raillane:

‘But Sir, why teach the child Ptolemy’s system of astronomy when you know it to be false?’

‘Sir, it explains everything and is in any case approved by the Church.’ (OI, II, p. 611)

Dr Gagnon, a man of science and the Enlightenment, was shocked, but did nothing to intervene. There could surely only be one outcome to Raillane’s sustained campaign against truth: Henry would eventually succumb to the parental and societal pressure being exerted on him, cease being atrocious and instead become a crook (coquin), like so many others before and since – in the process, he would stop being his own singular creation, stop being a Merteuil.

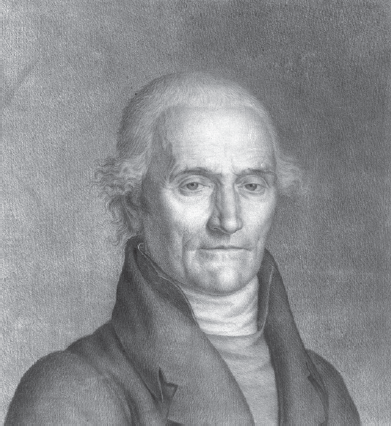

Anonymous artist, Jean-François Raillane, 18th century, engraving.

Had Raillane succeeded in his alleged endeavour, there would be no biography for me to write: Henri Beyle would have gone on to try to accumulate wealth and secure his social position in Grenoble, no doubt using his father’s connections to become a lawyer of some sort. He would have met family and class expectations: become another Candide Chenevaz. But Henry resisted, in part thanks to the influence of his great-aunt Élisabeth. The value she placed on personal honour and greatness of character meant she had very little time for stuffed shirts, including even her sweet-natured and cultivated brother. Throughout his own life, Stendhal wondered if he himself possessed greatness of character, whether in his thoughts or in his deeds: did he exemplify the qualities of generosity, courage, enthusiasm and authenticity embodied by his exemplars, Élisabeth included? Certainly, he wished to be singular. Why limit oneself to the words and behaviour expected by others, ideally to be reproduced only ever ironically and antiphrastically when in the presence of stuffed shirts, if one can instead speak and act impulsively, unpredictably and authentically when in the presence of friends? This, in essence, is beylisme: a defence and assertion of the singular self.

Élisabeth’s influence, however, also left Henry vulnerable, for it prevented him from seeing things as they are. It led him to overestimate the iniquity of others, starting with his unfortunate father Chérubin, aunt Séraphie and sister Zénaïde. It also led him to overestimate the worth of others, starting with his sister Pauline. Finally, it led him to adopt Élisabeth’s habitual hauteur, which worked against both his own and her instinctive generosity. The discovery of mathematics and logic – the discovery of truth – would, therefore, prove a welcome antidote not just to the values promoted by Raillane, but to those embodied by Élisabeth. It would allow him to think dispassionately of things as they are, starting with himself and his family.

As has already been noted, Stendhal would eventually come to see that his father had been devastated by Henriette’s death and that his father’s coldness was probably first a manifestation of extreme grief and then a response to that son’s own evident hostility; possibly it even led him to the realization that his father would have been perfectly entitled to pursue any sexual interest he might have had in Séraphie. Stendhal also came to see himself for what he was: a stocky, unattractive boy, anxious and odd, destined to grow up to be a stocky and unattractive man, at times very much in control of himself and at others not at all, perduringly anxious and odd despite all his increasingly confident displays of wit and intelligence.

The Raillane tyranny came to an end in 1794 when the ghastly Jesuit unexpectedly disappeared to take up a better job elsewhere. Then, in 1795, the Republic, Henry’s ideal parent, opened a school in Grenoble: Dr Henri Gagnon was called upon to lend his prestige to the foundation of this École Centrale. Perhaps as a result, and much to his delight, the twelve-year-old Henry was allowed to attend. Immediately, he felt part of a wider community of boys, or rather, he felt part of the Republic. His teachers were mostly of at least some inspiration and gave him a reasonable grounding in a range of disciplines. His favourite subject was, without doubt, mathematics, deemed the pure manifestation of truth: ‘How ardently did I adore the truth at that time! How sincerely did I consider it the queen of the world I was about to enter!’ (OI, II, p. 858) But M. Chabert, his mathematics teacher, found it difficult to answer Henry’s questions. Unable to explain and resolve the contradiction between two separate accounts of the properties of parallel lines, Chabert left Henry doubting whether his teacher was after all an adept of ‘the cult of truth’ (OI, II, p. 858). Was Chabert finally any different from Raillane? It is at this point, Stendhal claims, that he reached the first of two crossroads. Discouraged, he appears to have come quite close to submitting, that is to say suppressing his own critical lo—gique and so becoming a hypocrite. Had he done so, Henry optimistically argues, he would have become a rich man. But at what price?

This moment made a huge impression on him. He felt on the brink of giving up something he valued intensely about himself: the independence of mind – or ‘spirit of examination’– that went with isolation. Now ensconced in the École Centrale, what could be easier than to conform, swapping the singularity of his opinions and beliefs for easy and superficial companionship, and even for advancement?

Anonymous pseudo-portrait of Stendhal in his library, 19th century, oil painting.

I almost gave in. An able confessor, a proper Jesuit, would have been able to convert me at that moment by expatiating on the following maxim:

‘You can see that all is error, or rather that there is no such thing as either truth or falsehood, everything being a matter of convention. Adopt the convention that will most help you to be received by polite society. The rabble is Republican and will always sully that cause; side with the aristocracy, like the rest of your family, and we’ll find a way of sending you to Paris and of recommending you to women of influence.’ (OI, II, p. 859)

He could so easily have become a crook (fripon) at this point: succumbed to the vast Jesuit conspiracy begun by Raillane, and turned into a con artist – the drama of this Faustian struggle is replayed at some length in Lucien Leuwen. But fortuitously a second crossroads was reached, and the risk of giving in was definitively averted. In the process, Brulard and Stendhal both learnt, emotionally rather than intellectually, that friendship and love are indeed the products not of rivalry but rather of esteem.

Henry had been agitating to be given private lessons in mathematics, having identified a plausible tutor in Louis-Gabriel Gros, a surveyor and notorious Jacobin – his surname would eventually be given to Lucien Leuwen’s closest male friend. Eighty-year-old great-aunt Élisabeth ‘generously’ (OI, II, p. 860) came up with the necessary cash. Her heart and intelligence were those of a thirty-year-old, Henry observes (OI, II, p. 860): she had made it to 28 a long, long time ago and had barely aged since. Henry arranged for his first lessons.

What Brulard has to say about his first encounter with Gros, at the age of twelve, may appear hyperbolic, even absurd. Yet I would argue that he here gives his fullest attention to trying to express the exact truth of the matter:

In the end, chance had it that I saw a great man and did not become a crook. Here [. . .] the subject exceeds what can be expressed in words [the phrase is borrowed from Charles de Brosses: ‘le sujet surpasse le disant’]. I shall try not to exaggerate [. . .]

Encountering a man on the model of the ancient Greeks and Romans immediately made me want to die rather than not be just like him. (OI, II, pp. 859–61)

Gros was the first of what Brulard refers to as his ‘passions d’admiration’ (passionate admirations):

I adored and respected him so much that perhaps I displeased him. I have so often encountered this surprising and disagreeable reaction that it is perhaps as a result of an error of memory that I attribute it to the first of my passionate admirations. I displeased M. de Tracy and Mme Pasta by admiring them with too much enthusiasm. (OI, II, p. 863)

In De l’Amour, Stendhal defines love as admiration plus hope, which we might re-express as the formula: love = esteem + desire. Stendhal’s experience of friendship, at least after this first meeting with Gros, produced the even simpler formula: friendship = esteem. It is for this reason that Stendhal sometimes signed off his letters to close friends ‘salutation and esteem’. The absence of desire, as between Henry and Louis-Gabriel – not that Louis-Gabriel was not a beautiful man, all estimable people being beautiful: Stendhal believed that our habits of mind come to be etched on our faces – did not prevent esteem alone from manifesting itself as a form of passion. In all cases, whether autobiographical or fictional – as in the case of the friendship between Lucien Leuwen and Théodelinde de Serpierre – the intensity of this relation is founded on an esteem that takes the form of a profound and justified sense of the other’s exemplarity. Henry did not just like Gros, he wanted to be just like Gros.

All of Stendhal’s fiction would eventually turn on this notion of exemplarity. Mostly, Stendhal’s exemplars are historical or fictional – that is, in both cases, made up. But Stendhal had actually met some of his exemplars: not just Gros, Destutt de Tracy and Giuditta Pasta, but also Napoleon and La Fayette. We do not compete with our exemplars: we model ourselves on them, which is very different. They are in no way our rivals. We do not desire them, but rather esteem them, sometimes passionately.

Gros’ exemplarity took two different forms. He was, very clearly, Henry’s teacher, somebody who could finally be trusted to understand more and to explain what he understood. In other words, Gros possessed a superior perspective and was willing to let Henry share in it, to see through his eyes. But there was more to it than that: as has already been noted, Gros was a Jacobin, enthused by the new political ideals of the Republic. He had very little social standing but, despite his poverty, appeared in no way servile. He had a pride about him, as demonstrated particularly by the care he took over his appearance. Gros was in no way filthy or repulsive, whether physically or morally – he was the anti-Raillane, providing an example of freedom that helped his young charge overcome the last effects of the Raillane tyranny.

Stendhal is a writer much given to decrying vanity, which he identifies as having been a driving force within French society at least since the Renaissance, but which he believes became pervasively dominant only after 1815. What Stendhal means by vanity is caring about the perceptions of others and pretending to be what one is not in order to obtain social advancement – being a stuffed shirt. To a very large extent, Stendhal’s concept of vanity overlaps with what we might today term narcissism. But what he does not mean by vanity is pride. Mathilde de La Mole is a case in point: generations of critics have fallen over themselves to identify her as vain, narcissistic and therefore wrong-headed by Stendhalian standards, despite her being so manifestly right-headed by these same standards in so many of her ideas. Yet Mathilde’s awareness of what others think of her is very carefully distinguished by Stendhal, and by his narrator, from the impulse to pander to the expectations of others that marks almost everyone else in her society – including, to a very large extent, Julien. Like Gros, Mathilde is proud: she wishes only to satisfy herself and to live up to her own personal standards. From Stendhal’s perspective, we ought to esteem Mathilde: want to be like her, just as Henry wanted to be like Gros.

For Henry, Gros’ Jacobinism was finally neither here nor there. Mathilde admires Mme Roland and Danton in the same way that she admires Queen Marguerite de Navarre: esteem is not ideological, that is, constrained by what Stendhal dismisses as ‘partisanship’ (ORC, I, p. 614). In Lucien Leuwen, the fictional Gros is, in fact, made less admirable by his Republicanism, his vapid political utopianism clearly preventing him from seeing things as they are and making him at times dull company. Stendhal was, in fact, a political atheist, or put another way, a moderate liberal who thought most political opinions stupid. Writing as M. Van Eube de Molkirk, a characteristically silly pseudonym, Stendhal notes that he will be denounced as ‘a Jacobin, a Bonapartist, a sans-culotte, a lackey of Empire, etc.’ (S, p. 57) – Stendhal was very fond of the dismissive ‘etc.’ that allowed him to dispense with tiresome detail, his friends having already understood him perfectly well. Van Eube de Molkirk goes on: ‘The truth is that if I did have any political opinions to express, they would belong to the centre left, like those of the vast majority of people, and that I was born too late to have played any active role in the Revolution.’ (S, p. 57).

But the French Republic was more important to Stendhal than all this might suggest: all his life, Stendhal also remained committed to the affective charge of loyalty – and paranoia – engendered in him by the French Republic at the time of the Terror. Stendhal was a sensible liberal who nevertheless believed in political violence as the only way for the individual to fight against protracted injustice. As we shall see, Stendhal is the only major author of the French nineteenth century actively to have considered trying to assassinate the head of state.

The Republic was founded when Stendhal was nine; it was in effect, although not formally, suppressed when he was sixteen. The formative years of his childhood therefore played themselves out against the backdrop provided by a series of sensational political events. At the time of the Terror in 1793, Chérubin Beyle became politically suspect and briefly had reason to fear for his safety – he successfully hid in Dr Gagnon’s spare bedroom, which puts the zeal and competence of his persecutors into their proper perspective. Monstrously, young Henry’s sympathies were with the Republic.

On the national stage, Henry came to admire many of the leading revolutionaries, starting with Mirabeau and Grenoble’s own Barnave before settling very clearly on Mme Roland and Danton as his hero(in)es. The former was, by the time she was executed, a moderate. The latter played a part in her downfall as a leading member of the radical grouping known as La Montagne, before himself quickly succumbing to the Terror. Stendhal wanted to be both of these exemplars, just as Mathilde de La Mole wanted to be Mme Roland and Julien Sorel wanted to be Napoleon. As we have already seen, Stendhal valued the Revolution for the opportunities it gave to individuals to reinvent themselves by inhabiting new, freer identities; in a still more limited sense, he appears to have valued it for making him personally happy, not just by persecuting his father – lovely though that was – but thanks to the exemplary spectacle it provided.

As Stendhal surveyed the Revolutionary era, particularly with hindsight, he came to identify the familiar antagonism between con artists and their marks. The Girondins, Mme Roland included, were marks: idealists, eager to imagine that ordinary men and women would spontaneously rise up not just to defend the Republic but to participate freely, actively and disinterestedly in its functioning. Girondins, Stendhal decided, were no good at issuing orders to other people – as we have already noted, one of the definitions of happiness as far as Stendhal was concerned was to issue no orders and to obey none himself. Danton, by comparison, was a con artist, not unlike Napoleon. Both stole money and were otherwise corrupt; both abased themselves by employing expedients in the squalid pursuit of power. Nonetheless, Stendhal identifies Danton’s organization of the Republic’s defence by a conscript army and Napoleon’s Italian campaigns as the two grandest events in modern history, made possible precisely by Danton’s and Napoleon’s ability to issue orders and to have them obeyed.

Anonymous artist, Chérubin Beyle, 19th century, oil painting.

Mérimée tells us that Stendhal was never of the same opinion twice when it came to Napoleon. The historian Pieter Geyl takes this negative assessment and runs with it: according to Geyl, Stendhal never stopped to think about the emperor’s career – never troubled his head about the purpose of the ‘energy’ he attributed to his hero.1 It is easy to see how Geyl could have arrived at this conclusion, and easy also to see how the generosity of Stendhal’s outlook might have confused not just Geyl, but even Mérimée, astute though the latter could sometimes be about his friend. But, in reality, Stendhal spent an enormous amount of his time troubling his head about Napoleon’s career.

Brulard looks back at his adolescent self and notes with no little shame that Napoleon’s glamorous rise had been enough to turn his young head: ‘I accuse myself of having had this sincere desire: that the young Bonaparte, whom I imagined to be a handsome young man like a colonel in an opéra comique, should make himself the King of France.’ (OI, II, p. 864) Henry had failed to see Napoleon for all that he was – failed to see the truth. For Napoleon, if anything even more than Danton, was not just a leader of men, but a con artist. The charisma that seduced Henry from afar, as he followed the young general’s exploits first in Italy and then in Egypt, would eventually seduce him in person: Napoleon and later La Fayette were the two political figures who made the biggest personal impression on him, no doubt in part because both were also soldiers who had exhibited personal courage and generals who had demonstrated that they could win a battle – neither was a hypocrite in these two senses at least. But if Stendhal’s admiration for Napoleon as a great man on the Greek or Roman model – a modern-day Alexander or Caesar – never faded, his political assessment, especially of the emperor that Napoleon became, was to prove highly nuanced, and not only in retrospect.