Stendhal returned to Paris in 1821 with the same elusive goal in the back of his mind as when he had returned to Milan in 1814: to rediscover the freedom he had first experienced in the rue d’Angivillers in 1803. But he was too much in turmoil readily to perceive this aim. Instead, his thoughts continued to turn around his grim curiosity as to how political events would unfold – the Restoration being surely doomed to fail – and around his lingering wish to blow his brains out. It was this confluence of ideas that led him briefly to entertain a course of action even more drastic than his suicide.

Stendhal was a very odd kind of Romantic. Octave de Malivert, the (anti-)hero of his first novel, Armance, kills himself by secretly taking poison and then pretending to die of natural causes while travelling to Greece ostensibly to emulate, but actually only superficially to imitate, Byron – the latter had of course died in Missolonghi in 1824, not poetically fighting the Ottomans but prosaically succumbing to fever and sepsis. This course of (in)action makes Octave quite a conventional Romantic hero: he’s self-defeatingly and self-pityingly ambivalent both about his participation in society and about his relationship with the woman he simultaneously loves and rejects, all in the manner of Chateaubriand’s René, Constant’s Adolphe, Duras’ Olivier and so on. In Stendhalian terms, however, Octave is no kind of hero at all, for he merely deludes himself that he is following in Byron’s footsteps: Byron doesn’t kill himself as part of a compulsive strategy of avoidance; rather, he happens to die while trying to impart meaning to his life, the way Stendhal’s hero(in)es, Octave apart, each try to impart meaning to theirs. Stendhal knew Byron personally just about well enough – he had very briefly met him, and anyway read about him in the Edinburgh Review – actually to have liked and admired him. By comparison, Octave is a very poor sap indeed. In 1821, however, Stendhal was a poor sap also. His eventual clear-eyed account of Octave’s vulnerability and self-loathing is therefore founded just as much on identification and empathy as it is on detached amusement. But Stendhal wasn’t only a sap in 1821: he was trying to impart meaning to his life, if necessary by imparting meaning to his death.

Stendhal discusses all of this himself. In the Souvenirs d’égotisme (1832), he offers the following layered account of his state of mind:

‘The most terrible of misfortunes’, I exclaimed to myself, ‘would be if the male friends amongst whom I now live, themselves so cold, were to guess at my passion, and for a woman I’ve never had!’

I told myself this in June 1821 and can see now for the first time, as I write these words in June 1832, that this fear of mine, which I must have repeated to myself a thousand times, was in fact the guiding principle of my life for a decade. It’s as a result of this fear that I became a wit. (OI, II, p. 434)

The reference to not having ‘had’ Métilde is an example of Stendhal’s habitual free indirect discourse, as revealed by the exclamation mark: this is not his opinion but the likely opinion of his cold – the French is, in fact, sec (dry) – male friends. What he feared was their all-too-predictable cynicism: What? All this fuss over a woman, and now you’re telling me you haven’t even slept with her? It is in the light of this fear that we should read both his not telling Mérimée about Métilde and the former’s reports of his friend’s alleged attitude to women. Stendhal did not necessarily tell his male friends what he was really thinking. Instead he tried to amuse them with his wit, as a way of hiding his true feelings and in the hope of thus preserving them inviolate. One of his favourite jokes was to feed his male friends their own opinions in exaggerated form, thereby both scandalizing and confusing them. ‘God gave us language to hide our thoughts’ (ORC, I, [Le Rouge et le Noir]). Stendhal eventually became a very funny man on the Parisian social scene as a way of concealing both his unhappy passion for Métilde and his resulting desire to blow his brains out, but not until the winter of 1826: ‘before then, I’d remain quiet out of laziness’ (OI, II, p. 541). George Sand, who met him travelling on a steamer from Lyon to Marseille in 1833, offers the following impressions of meeting Stendhal in her Histoire de ma vie (The Story of My Life, 1854–5):

He was brilliantly witty and his conversation reminded me of that of [the novelist and journalist Henri de] Delatouche, only less delicate and graceful, but more penetrating. At first glance, he was also like Delatouche physically: fat, with very fine features under all the puffiness of his face. But Delatouche was rendered beautiful, from time to time, by sudden melancholy, whereas Beyle’s expression remained satirical and mocking at all times. [. . .] Above all, he affected disdain for all types of vanity and endeavoured to uncover some form of pretention in each of his interlocutors in order to subject it to the sustained fire of his mockery. But I do not believe that he was unkind: he tried far too hard to appear so [. . .] We separated [. . .] after several days of jovial conviviality; but, given that the back of his mind betrayed a taste for obscenity, whether in his habits or his dreams, I confess that I’d had enough of him.1

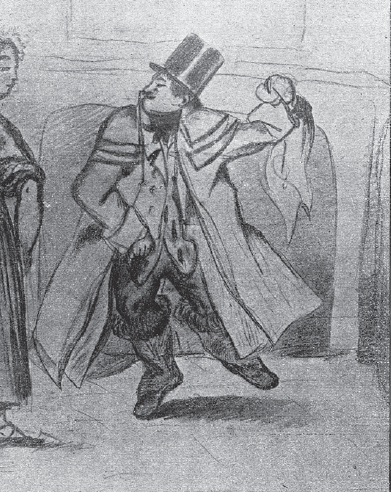

Sand never fully penetrated the back of Stendhal’s mind, thrown off, for example, by the ‘somewhat grotesque and not at all pretty’ spectacle of watching him dance drunkenly around the table in a tavern.2 She understood that he was making mock by his outlandish behaviour, but not the sentiments that underpinned that mockery. In this, she was little different to his friends. Most of these friends Stendhal had known since his school days: Romain Colomb (the eventual executor of his will), Louis Crozet, Louis Barral, Édouard Mounier, Félix Faure. He distanced himself from these last two as they advanced in their political careers and defended policies he considered to be ethically unacceptable, but generally Stendhal’s friendships, including with his former lovers, are striking for their longevity. In the 1820s Stendhal acquired an additional circle of close and trusted friends: Destutt de Tracy, the painters Gérard and Delacroix, the naturalist Georges Cuvier, Giuditta Pasta, Mérimée, Adolphe de Mareste, the Neapolitan exile Domenico Fiore and the English liberal Sutton Sharpe. The men in this group, especially Mérimée and Mareste, tended to laugh at overt displays of emotion. As a result, Stendhal would reveal what he was really thinking much more often to his female friends, with whom he was really quite warm, and even, on grand occasions, moist (in his words, humide): Stendhal was prone to emotivity, sincerity and tears. He wanted, at all costs, to protect this aspect of himself: allow himself to continue feeling something for his fellow human beings so that, when the opportunity arose, he could still make meaningful connections with the likewise sincere – we few, we happy few, we band of brothers and sisters. This is the meaning of the ending of Lucien Leuwen, which sees Lucien travel to take up a post in Italy while succumbing to ‘tender melancholy’ and ‘a state of emotion and sensitivity to the slightest things’, before lecturing himself, in the novel’s final sentence, on the need ‘to adopt a seemly degree of aloofness towards the people he was about to meet’ (ORC, II, p. 716). Stendhal wanted to find a special language with which to not hide his thoughts from the people he trusted and, mostly, these people were women. The rest of the time, he wore a cold mask of impassivity.

Newspaper reproduction of a sketch of Stendhal dancing drunkenly in a tavern, by George Sand’s lover Alfred de Musset (1810–1857).

To return to Stendhal’s own account of his state of mind in June 1821, he clearly felt himself to be very isolated, far from the woman and the friends and the city that he loved:

I entered Paris and found it worse than ugly – an insult to my despair. I had only one idea in my head: not to allow my thoughts to be discovered. After a week in the political vacuum of Paris, I told myself: ‘Take advantage of my despair to k[ill] L[ouis] 18.’ (OI, II, p. 434)

Find out what the next political development would be? Check. End it all? Check. But how serious was Stendhal? Probably not enough to have produced a detailed plan of action; probably enough to have spent entire minutes at a time convinced that he would go through with the assassination of France’s elderly, obese, in all senses impotent, restored monarch. In 1820 Louvel’s assassination of the Duc de Berry, Louis XVIII’s heir and seemingly the last plausible continuator of the Bourbon line, had no doubt reminded Stendhal of his childhood fascination for tyrannicides. Why not go out with a splash like Charlotte Corday? Certainly it would have been easy enough to kill Louis XVIII, even just on the spur of the moment: he was often to be seen patiently sitting in his carriage as it was being pulled along at a stately pace through the streets of Paris.

Killing himself by first killing Louis XVIII would not only have hastened the demise of the Bourbon line, but served as a wonderful red herring: had Stendhal acted, who would ever have guessed that his true object would in fact have been to escape the relentless grief produced by his definitive loss of Métilde? Certainly none of his male friends. In the end, though, Stendhal decided not to kill Louis XVIII, but instead to visit England.

On his journey, Stendhal stopped off in a tavern in Calais, where a drunk English sea captain insulted him. Stendhal failed to realize the seriousness of the incident until his travelling companion, a memorably blond Englishman unimprovably named Edward Edwards, told him he ought to have challenged his antagonist to a duel:

I’d already made this horrible error once before, in Dresden, in 1813, when dealing with M [blank], who subsequently went mad. I do not lack for bravery; such a thing could no longer happen to me now. But, in my youth, when I improvised I was mad [. . .] Mr Edwards’s intervention had the same effect on me as the cock crowing had on St Peter. (OI, II, p. 476)

Stendhal clearly takes his failure in Calais extremely seriously, so seriously in fact that he misremembers when it occurred. Edwards had in fact been his travelling companion in 1817, when he had first spent two weeks in London, and not in 1821 when he was escaping Paris and the prying eyes of his friends. There is a reason for the slip of memory: Stendhal’s failure to challenge the English sea captain to a duel is emblematic of his state of mind not in 1817, when he still felt relatively jaunty, but in 1821, when he had fallen apart. The Souvenirs d’égotisme are all about the decade it took him to pull himself back together. Put another way, they are all about his succumbing to emotion and trying to restore himself to reason. De l’Amour had similarly been written with the idea of establishing the critical distance that might allow him to survive the collapse of his last remaining hopes with regard to Métilde, by proving to himself that his feelings for her were, in fact, so many symptoms of a human affliction; that his love for her was, in fact, what might today be labelled limerence – an involuntary state of adoration producing obsessive thoughts, rapid swings from euphoria to despair and the strong desire to have one’s feelings reciprocated. But Stendhal was sufficiently Romantic to believe that what he felt for Méthilde was more than the disordered state of mind he dispassionately set out to describe as though he were simply an Ideologue – however ridiculous, delusional or weird, his sentiments were also noble, disinterested and true. It is Stendhal’s awareness of complexity – his own and that of others – and his refusal to reframe human beings in terms of reductive narratives that prompted him to write Armance, perhaps the least understood and least understandable French novel of the nineteenth century.

For the time being, Stendhal was still prudently holed up in London. He went to the theatre and generally overdosed on Shakespeare as a way of communing with Métilde. A couple of his friends, Mareste and Rémy Lolot, were also in town. To distract him, they decided to take Stendhal to a brothel. Already in Paris, some of his male friends had arranged for him to visit a prostitute in their company: he had not managed to perform sexually, despite or because of the extraordinary splendour of her person. ‘In 1821, love gave me a very funny virtue: chastity’ (OI, II, p. 444). It is on the strength of this first Parisian episode that Stendhal enjoys his ongoing reputation for sexual dysfunction – the stupendously detailed surviving record of his relentless sexual activity notwithstanding. His decision to include a chapter entitled ‘On Fiascos’ in De l’Amour hasn’t helped in this regard. Now, only a few months later, he once again found himself being dragged along on an expedition designed – but hardly calculated – to cheer him up. Yet, against all his expectations and despite his fear of further humiliation, Stendhal found the experience completely enchanting, as he recounts in the Souvenirs d’égotisme.

Miss Appleby and her two friends lived together on an equal footing in the smallest three-storey house Stendhal had ever seen. The young women, all very English with their chestnut hair, pallid skin and reserved manners, appeared embarrassed by the finery of their French visitors, just as Stendhal and Lolot appeared embarrassed by the indigence of their surroundings – in the end, Mareste had been too scared to come, fearing an ambush; it was only the possibility that the expedition would in fact end in an armed confrontation with a gang of English pimps that finally determined Stendhal and Lolot to embark on it. It turned out that Lolot being ‘tall and fat’ and Stendhal being ‘fat’, they could not bring themselves to sit on the tiny chairs: ‘they seemed to have been made for dolls; we were scared of them giving way beneath us’ (OI, II, p. 484). An awkward silence ensued.

Remembering their duties as hosts, the young women offered to show their guests the garden. It was 7.5 metres (25 ft) long, 3 metres (10 ft) wide, and largely taken up by the basin in which they washed their clothes and a contraption that allowed them economically to brew their own beer. Lolot was disgusted and wanted to leave; Stendhal was touched and worried about humiliating the young women, now reduced to two in number. He lost his own sense that he would be either humiliated or assassinated and spent the night with Miss Appleby, who seemed quite alarmed by the number of weapons he had brought with him and insisted on turning down the light out of modesty. The following morning, Mareste was summoned to bring wine and food: this bounty was left to the two women and the two men promised they would return later that evening.

Stendhal thought of his impending reunion with Miss Appleby all day: he had lit upon the English phrase ‘full of snugness’ (OI, II, p. 486) as a way of putting his new sensations of tranquillity into words. When he arrived with Lolot, he came bearing ‘real champaign’, as the young women excitedly pointed out. When the cork popped, they expressed great happiness, in calm and measured tones: ‘This was the first real and intimate form of consolation for the despair which poisoned my every moment alone. It’s plain that I was only twenty in 1821.’ (OI, II, p. 486)

Stendhal was in fact 38, but he was still sincere – not admirable, but sincere – in the manner of a much younger man. Miss Appleby eventually asked Stendhal if she could come to Paris with him – she apparently claimed she would eat only apples and cost him nothing. He thought about it and was deterred by memories of how difficult he had found it briefly living with his sister Pauline in 1816. It may in fact be Miss Appleby who, for a few minutes in 1821, came the closest to making Stendhal want to feel responsible for another human being. He really liked her and her company; he liked providing for her; but in the end, he didn’t want to be responsible for anybody – it was a choice he had made for himself, at least after realizing that he would never be allowed to be a support to Métilde. Stendhal’s conception of freedom worked both ways: he wanted himself to be free and assumed that everybody else wanted to be free also. He therefore ruled out formal ties with the people he loved, but that didn’t stop him from loving those people. In a nutshell, this is Stendhal’s conception of égotisme: it is what made him a warm and reliable person, full of good will and loyalty, and it is quite possibly why he never married or had children.

What Stendhal most liked about Miss Appleby was her complete lack of false airs: ‘To my misfortune, I so dislike affectation that it’s very difficult for me to be unaffected, sincere and good, or in other words perfectly German, when I’m with a French woman.’ (OI, II, p. 488) Was Stendhal sincere with women? He loved their company; he loved their conversation; often, but not always, he wanted to sleep with them; typically, he admired them, far more so than he did men; he thought them capable of sincerity (as, for example, Métilde) but he also liked them when they were insincere (as, for example, Angela and eventually Alberthe de Rubempré) so long as they were magnificently insincere and not squalidly, self-servingly so. Perhaps, therefore, he recognized that he could himself be insincere with women, although, hopefully, only ever magnificently so, insincerity being sometimes to sincerity what literary fiction is to truth. Certainly, he remained all his thinking life aware of the grotesque imbalances of power and status between men and women, even as he often took advantage of these. Perhaps what Stendhal found touching about Miss Appleby was the patience with which she fought for a better life even as it must have been clear to her that the entire system was rigged against her, hence the sudden presence of a fat paying Frenchman in her bed.

Stendhal was more generally impressed, as well as appalled, by the patience of the English. He had never seen a people work so hard and for so little money; he had no idea why they did not rise up against their employers: ‘The exorbitant and oppressive labour performed by the English worker avenges us for Waterloo and the four coalitions. At least we’ve now buried our dead and those of us who survive live happier lives than the English.’ (OI, II, pp. 482–3)

Stendhal taught himself political economy on and off for most of his adult life, and in 1825 he even went so far as to write a political pamphlet attacking the French Industrialist lobby. His main contribution to the field was the thought that political economy focuses on economic prosperity and growth without giving any proper consideration to human happiness. Insofar as there is an argument for work – and Stendhal could see how it might make sense simply to loaf around in Naples looking at the view and soaking in the sun – that argument must concern itself with the happiness work procures us or the mental pain it spares us – from 1821 to 1832 work helped spare Stendhal the mental pain of thinking too much about Métilde. It is for this reason that he started contributing articles to the English and French press, published De l’Amour, produced a biography of Rossini, wrote two pamphlets in support of his idea of Romanticism, revised and added to Rome, Naples et Florence and wrote his first novel, Armance, all between 1822 and 1827. Equally, taking plentiful holidays spared him the mental pain of thinking too much about Métilde, who died on 1 May 1825, bringing their already off-off relationship to its final stage of nonexistence. ‘Death of the author’, Stendhal noted in the margins of a copy of De l’Amour (DA, p. 422), putting Barthes and literary theory into their proper context. Always interested in the truth, Stendhal notes in the Vie de Henry Brulard that he recovered from her death really quite quickly, having already grieved for her so long in life: ‘I preferred her dead to faithless; I wrote, I consoled myself, I was happy’ (OI, II, p. 541).

Stendhal was fantastically good at finding ways to take leave, especially sick leave and unauthorized leave. It will be remembered that even his pseudonymous self was a cavalry officer on leave in Italy. As we shall see, when he lived in Italy he in fact spent much of his time on leave in Paris. When he lived in Paris, he spent much of his time on leave in Italy or, as in 1821, in England. Adrift as Stendhal was after losing Métilde, he knew that he needed to continue to hunt for happiness and that he would probably most likely find it in unexpected places. For example, in London, and more especially in Richmond, he found that English trees made him happy. He liked the way they were planted asymmetrically and seemingly allowed to grow free (OI, II, p. 478). All in all, London had proved an unexpected success.

Back in Paris in 1821, Stendhal tried to hide his melancholia with jokes. It turned out he was a funny man, and it was on that basis that he was allowed to make himself at home in literary and intellectual salons that without him continually ran the risk of listing into boredom. In 1822 he spent a lot of his evenings with his neighbour, Giuditta Pasta, in the rue de Richelieu, marvelling at the simplicity and generosity of one of the great operatic divas of the early nineteenth century. He also regularly attended the salon of one of his intellectual heroes, Destutt de Tracy, making friends with his family. He had first met Destutt in 1817, just after his return from that first trip to London: the great man spent fully an hour and ten minutes visiting Stendhal in his rooms and two days later sent him a copy of his latest book.

Destutt’s salon proved attractive also because La Fayette, internationally famous ever since his emergence as a hero of the American War of Independence, was one of its leading lights:

I immediately understood, without being told, that M. de La Fayette was quite simply a hero from Plutarch. He lived from day to day, not particularly intelligently, like Epaminondas performing the great deeds that presented themselves to him. (OI, II, p. 455)

Michele Bisi (1788–1874), Giuditta Pasta as Desdemona in Rossini’s Otello, 19th century, lithograph.

When not performing great deeds, La Fayette apparently filled his spare time pursuing inappropriately young women and mouthing the platitudes of a simplistic liberal politics. To the untrained eye, there didn’t seem to be all that much to admire, but for Stendhal, ‘accustomed to Napoleon and Lord Byron [let’s allow him his poetic licence], and for that matter to Lord Brougham, Monti, Canova, Rossini [he liked to pretend he’d met Rossini one day in an Italian inn: he hadn’t], I immediately recognized M. de La Fayette’s grandeur and that was enough for me’ (OI, II, p. 456).

Retrospectively, Stendhal can see that he lived his life in this period ‘from day to day’, in the manner of La Fayette: ‘I have always lived and live still from day to day, never thinking of what I shall do tomorrow’ (OI, II, p. 440); ‘I’ve never had enough good sense to arrange my affairs systematically. Chance has guided all my relationships’ (OI, II, p. 489). Stendhal uses this narrative of a haphazard existence, governed only by chance, (not) to explain his life in the period after his return to Paris in 1821:

Have I extracted the greatest possible happiness from the various situations in which chance has placed me over the course of the nine years I’ve just spent in Paris? What kind of man am I? Am I possessed of good sense? Is my good sense accompanied by penetration? Is my intelligence remarkable? Truth be told, I’ve no idea. Affected emotionally by what happens to me from day to day, I rarely give any thought to these fundamental questions, and when I do, my judgements vary according to my moods. My judgements are no more than fleeting insights. (OI, II, pp. 429–30)

The next paragraph shows why writing was the activity that finally consoled him for the loss of Métilde: ‘let us see if, examining my conscience pen in hand, I’ll manage to find something positively and lastingly true about myself’ (OI, II, p. 430). Writing allowed him to make some sort of sense of the person he was: find the fictional narratives that alone could account for the past, and in particular the women he had loved: ‘Most of these charming beings did not bestow their favours on me; but they literally occupied my entire life. They were succeeded by my writing’ (OI, II, p. 542). Stendhal loved, and then he wrote, as his projected epitaph emphasized. Without the narratives of his writing, it would have been as though he and his loves had never existed.

Ary Scheffer, Marquis de Lafayette, 1823, oil painting.

Stendhal allowed for the possibility that most people do not really exist, trapped in superficial and narcissistic narratives of the self that bear no relation to truth. He thought that, through writing and more especially through fiction, he could do better. In his life to date, he had been relatively pleased with himself, some mishaps such as the unfortunate incident in Calais apart. Like La Fayette, he had performed the great deeds, or at least the deeds, that circumstance had made possible for him. But writing gave him the chance to reflect on the five or six great questions that mattered to him and so to become fully adult: ‘I cannot conceive of a man without at least some male energy, without ideas that are constant and profound, etc.’ (OI, II, p. 451).

One of these ideas related to what we might term ‘female energy’. Just because he had lost Métilde doesn’t mean he had lost his capacity to esteem women. In 1824 he started an affair with Countess Clémentine Curial, codename Menti, identified by him as the most intelligent of the women he had loved, just as Métilde had been the noblest in her sentiments (OI, II, p. 545). He had first met her ten years earlier, at 6 a.m. on 18 March 1814, aged 26 and alluringly barefoot while dropping by to report the outcome of the battle of either Montmirail or Champaubert (in fact, the battle of Arcis-sur-Aube) to her anxious mother (OI, II, p. 517). This had turned out to be the erotic highlight of that particular year. Menti had been quite taken with him too, or so it eventually turned out, for in 1824 she seduced him. He could hardly believe it. He tried ‘not to let my soul become absorbed by the contemplation of her graces’ (OI, II, p. 780). He failed, and the result would be further heartache two years later: ‘The astonishing victory with Menti didn’t even give me a hundredth the pleasure than the pain she caused me by leaving me for M. de Rospiec’ (OI, II, p. 533):

What a year I passed from 15 September 1826 to 15 September 1827! The day of that horrific anniversary, I was on the island of Ischia, and I noticed a definite improvement: instead of thinking directly about my misfortune, as a few months earlier, I only remembered the melancholy in which I had been plunged in October 1826 for example. This observation consoled me greatly. (OI, II, p. 532)

One of the things Stendhal had loved about Menti was her tendency to defend him when he went too far with his jokes (OI, II, p. 635). This happened frequently, even before the winter of 1826 when, having lost Menti, he really could not have cared less about the consequences of what he said: ‘I seemed atrocious to all those pygmies so diminished by the politeness of Paris’ (OI, II, p. 464). Lots of the people who met him thought he was completely awful; the people he most liked in the entire world were the women who noticed that he was, in fact, joking.

At the end of 1826 Stendhal was back to square one: trying to get over Menti’s rejection of him and trying to make jokes as a way of deflecting unwanted attention from his male friends. But he quickly moved to square two: in 1827, aged 44, Stendhal finally wrote a novel – one exclusively for the men and women who might possibly understand that he was, in fact, joking. The project was, in any case, intended to be parodic. Claire de Duras had written a succession of brief novels about thwarted love: love thwarted by racial difference (Ourika, 1824), love thwarted by class difference (Édouard, 1825) and love thwarted by erectile dysfunction (Olivier ou le secret (Olivier; or, The Secret), unpublished). As a self-proclaimed expert on the latter delicate topic, Stendhal decided to write his own novel with a view to publishing it anonymously and so implicitly passing it off as Duras’ self-censored text. This intention was obscured by his choosing the title Armance and naming his anti-hero Octave rather than Olivier. It was further obscured by his only hinting very subtly, if at all, at Octave’s sexual impotence. The novel is a joke on its author in a variety of ways: it is a novel that sets out to frustrate its readers (a strange way to launch a career as a writer of fiction); it is a darkly comic novel about the poor sap that Stendhal had himself been in 1821, and had become again in the months that succeeded 15 September 1826; it is an attack on Romanticism written by an ostensible champion of the Romantic cause. The story tells of how a potentially impressive young man falls in love with an actually impressive young woman who very clearly reciprocates his feelings. Perversely, he misreads her, preferring his own paranoid narratives. He miscommunicates with her unaccountably over and over again until he despairs and finally kills himself. It is just as well that so few people read it at the time, given how incomprehensible they would likely have found it.

Anonymous artist, terracotta bust of Clémentine Curial, 19th century.

The novel exposes the problem of the near-impossibility of male heroism, while starting to explore the possibility of female heroism, in the France of the Restoration and indeed in the modern period ushered in by the fall of Napoleon. As its preface points out, the nineteenth century only started in 1815; arguably, we are still in that century: Armance is a novel about what it is to live amid the political, social and gender cleavages created by the French Revolution’s brutal strangling at birth of women’s rights, as finally enshrined in the Napoleonic code. Put another way, it is a novel about the Restoration, about the fraudulence of patriarchal authority and power. Put another way still, it is a novel about how the penis no longer works. Armance functions as a mirror held up to the French society of 1827. In 1829 Stendhal would write Le Rouge et le Noir, a novel that holds up a mirror to the France of 1830, but that also shows us what no mirror could ever fully capture.