Stendhal was a perverse man. When not in Paris, he pined for Italy; when in Italy, he pined for Paris. When in Civitavecchia, more understandably, he pined for most other places. ‘Sun every day,’ he noted mournfully on 17 April 1831: ‘I’ve already reached the stage of praying for rain’ (CG, IV, p. 138). So much for azure skies. It further turned out he did not at all enjoy the business of being a consul, at least not in a minor port endemically stricken by malaria. He was supposed to be overseeing the way French vessels were treated by Papal customs officials; he wanted to be conducting high diplomacy. As a result, he decided to hand over as much as possible of his work to his subordinate and to write very long and clever letters to his superiors about how they might better conduct the affairs of state. These proved to be poor decisions.

Stendhal’s subordinate – the French consulate in Civitavecchia hardly abounded with subordinates for the purposes of delegation – initially struck him favourably, in the one sense that he seemed biddable. It is for this reason that he ignored his predecessor’s parting advice to adopt extreme caution when dealing with Lysimaque-Mercure Caftangioglou-Tavernier, soon to become the bane of Stendhal’s life. Half-French, half-Greek, Tavernier has come down to us as a kind of Mediterranean Uriah Heep. When Stendhal found him, he was performing the duties of chancellor of the consulate, but without in fact having been appointed to this post and consequently without remuneration. Stendhal eventually helped Tavernier secure this position permanently on 19 May 1834, not that this helped improve their relations. Indeed, after particularly harsh words on both sides, Stendhal accepted Tavernier’s resignation on 7 June, only to find himself forced to reappoint him a week later. Clearly, a lot of Stendhal’s bad temper while performing his duties related to the nature of those duties and the town where he was required to perform them, but it did not help that he henceforth found himself both stuck with, and to a large extent dependent on, a compulsive and malevolently oleaginous liar. That dependency was, of course, his own fault: had he been willing to stay in Civitavecchia and do his work assiduously, he would doubtless neither have needed Tavernier nor himself remained for long in such a lowly post. Instead, he took heroic amounts of sick leave, to some extent with the connivance of the French ambassador in Rome.

Already in the summer of 1831, he was off to Albano and Grottaferrata in search of clean air and pleasant company in the hills south of Rome; when he had had enough of that, he returned to Rome, where he behaved as though in Paris, making jokes that terrified his audience, well aware that they could get into serious trouble just by listening to the outrageous things he said. George Sand offers us the following account of visiting Avignon’s Notre-Dame des Doms with Stendhal in 1833:

In the corner, an old painted wooden Christ, life-sized and truly hideous, became for him the subject of the most incredible commentary. He had a horror for such repulsive monstrosities, prized by the people of the South, or so he said, for their barbarous ugliness and brazen nudity. He wanted to attack the image with his fists.1

We may judge the effect of his various outbursts when in the Papal States themselves by the slyly charming reprimand sent to him in 1832 by Louise Vernet, the wife of the director of the French Academy in Rome and, consequently, Stendhal’s frequent host:

I’ll wager that you do not realize, Sir, that I am very cross with you. This unawareness makes you all the more culpable in my eyes. I want to give you the opportunity to atone for your misconduct by asking you to come dine with us next Sunday (24 June) at precisely eight o’clock. There will be a small company. I shall have an opportunity to set out my grievances and to take my leave of you for I am planning to leave Rome for some time. Horace and I would be very upset if you were to send your excuses. Do not add a further misdeed to all your others. (CG, IV, p. 460)

In this period, Stendhal made friends with Donato Bucci, a dealer in Etruscan vases, the wealthy Cini family in Rome and Abraham Constantin, a painter from Geneva, with whom he shared rooms near the Spanish Steps. Another favourite destination was Siena.

Giulia Rinieri, it turned out, had no interest in marrying Stendhal, marrying a cousin instead in 1833: no woman ever proved irresponsible enough to accept one of Stendhal’s proposals. She did, however, want to remain in touch with him. Even as passion cooled on her side, she continued to profess deep friendship for Stendhal and, astonishingly, she appears to have been entirely sincere in doing so. If Stendhal kept going back to Siena, mildly to the interest of the Austrian-controlled police, it was in large part to meet up with her when she was visiting her hometown.

In 1832, Stendhal spent at best a third of the year in Civitavecchia; the rest of his time he divided fairly evenly between new travels around Italy and extended sojourns in Rome. He started and discontinued an autobiography, the Souvenirs d’égotisme; he then started and discontinued an autobiographical novel, Une position sociale, telling the story of a certain Roizand, secretary to the French embassy in Rome, in love with the ambassador’s wife – echoes of his feelings for Alexandrine Daru. In 1833, when once again in Rome visiting the Caetani library, he acquired copies of a job lot of manuscripts chronicling various Italian scandals of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Immediately, it occurred to him that they would make for fine source material – but he was too indolent to do anything with them for the moment. Eventually, though, it occurred to him that he ought to do something productive with his time. So, in 1834, he mostly stayed put in Civitavecchia and Rome, working on a new project.

In the autumn of 1833, Stendhal had been on leave, this time in Paris. He had spent a few days staying with Clémentine Curial – it is to Stendhal’s credit just how much his lovers all seemed still to like him, even after they had left him. He also caught up with another old female friend, Mme Jules Gauthier, who gave him a copy of a novel she had written, entitled Le Lieutenant. This he finished reading at the start of May 1834, when he finally wrote to her with his suggestions, which included that she revise the novel completely and change the title to Leuwen, ou l’élève chassé de l’École Polytechnique (Leuwen; or, The Student Expelled from the École Polytechnique). Helpfully, he had already started rewriting her novel for her, when he suddenly had another of his brilliant ideas: ‘don’t send it to Mme Jules but make of it an opus’ (OI, II, p. 195). What better subject, when wilting under the azure skies of central Italy, than the rain of northeastern France.

Lucien Leuwen is a political novel – along with Flaubert’s L’Éducation sentimentale (A Sentimental Education, 1869), arguably the great French political novel of the nineteenth century. In the autumn of 1833, Stendhal had met and spent some time with Clémentine Curial’s disgruntled legitimist friends, nostalgic for the Bourbons and their own lost political clout; he had also witnessed at first hand the staggering lack of enthusiasm among all classes for Louis-Philippe (his decision to designate himself King of the French as opposed to King of France notwithstanding) – it turns out you need to be popular to be a populist. It was time to write once again about the muddy roads of France.

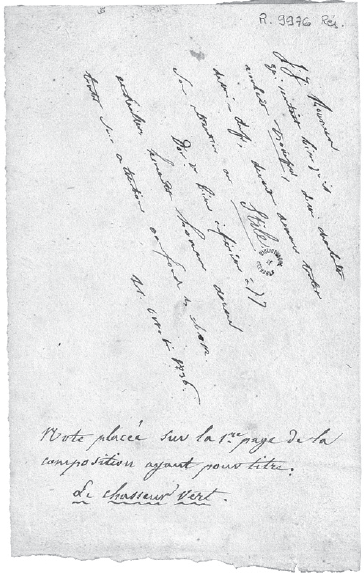

Manuscript note by Stendhal, on an unbound sheet, formerly the first page of Le Chasseur vert (The Green Huntsman), the first volume of Lucien Leuwen: ‘J.-J. Rousseau, who understood perfectly well that he wished to deceive, half a charlatan, half a dupe, had to give his full attention to his style. / Dom[ini]que, far inferior to J.-J. and for that matter an honest man, gives his full attention to getting to the bottom of things. 21 October 1836’ (OI, II, p. 283).

When Napoleon fell in 1814, one of his generals, Jean Lamarque, was told by a minister in the new government that France would finally get a rest from all the turmoil of the Revolution and empire. He is said to have offered the following reply: ‘That’s not a rest you’re talking about: it’s a halt in the mud’ (OI, II, p. 1271). Lucien alludes to this phrase when he likewise characterizes the Orleanist monarchy as ‘a halt in the mud’ (OI, II, p. 91). Orleanism, even more than the Restoration, exemplified the permanent disenchantment generated by the failure of the Revolutionary project, broadly construed. Its seeming purpose was simply to contain the anger of the working classes; its citizens lived in fear not so much of the government, which was largely impotent, but of each other, everyone having, in some way, compromised and betrayed his or her own ideals. How to earn the trust of others when one lies habitually to oneself? Muddy Orleanism exemplified ‘the genius of suspicion’ (OI, II, p. 430) that defines modernity, or what Nathalie Sarraute, after Stendhal, dubbed ‘the era of suspicion’, in an essay of that same title published in 1956. Stendhal is talking about the end of the Revolution’s Rousseauvian dream, whether utopian or dystopian, of free citizens hiding nothing from each other, needing in fact to hide nothing from each other on account of their upholding the same universal values. It is this dream that Stendhal hopes to realize in his sincere communication with the happy few. But he is aware that most readers of Lucien Leuwen, as of his other works, will be suspicious of him just as he, in his turn, is suspicious of them. Luckily, they don’t understand a word he’s saying.

Lucien Leuwen is also an intensely personal novel. If Une position sociale started to tell the story of Stendhal serving as a French diplomat in Italy, Lucien Leuwen tells the story of Stendhal serving the empire in Germany, but with the action bathetically transplanted to Orleanist France. The first book of the novel is largely set in Nancy, but actually the ‘café-hauss [sic]’ that Lucien visits on the outskirts of the city is Der grüne Jäger (The Green Huntsman), the establishment Stendhal remembered frequenting in Brunswick, while paying his court to Mina de Griesheim in 1807 – Mina had, of course, returned to the forefront of his mind when he wrote Mina de Vanghel in 1829, and she would keep popping up, for example when he composed first Tamira Wanghen and then Le Rose et le Vert in 1837.

Lucien Leuwen is also, like Armance and Le Rouge et le Noir before it, a novel about high society. Lucien must make his way around first the salons of Nancy and then the salons of Paris. Almost everyone he meets is both dull and false, yet how can he ever find anything out about himself if he doesn’t engage with things – and people – not as they should be, but as they are? Lucien Leuwen, even more than Le Rouge et le Noir, is a novel about surviving in the midst of relentless mediocrity.

Lucien Leuwen is also a novel about friendship. Stendhal writes often about friends, typically as very minor characters who nevertheless offer the protagonists both empathy and loyalty at key moments of distress. In the novel, the hero’s friendships with Gauthier – named after Mme Jules Gauthier, but modelled on Louis-Gabriel Gros from Grenoble – and even more importantly with Coffe and with Théodelinde de Serpierre are each brought into the foreground of the text. Gauthier is necessarily a distant figure, based as he is on a much older former teacher: he is entirely admirable and therefore finally limited in a novel that shows just how well Stendhal understood that there is no such thing as ‘entirely admirable’ in this world pieced together out of the broken ideals of the French Revolution. Coffe and Théodelinde de Serpierre, by contrast, are Stendhal’s pen portraits of his friends, both male and female.

Coffe is fair-minded, critical and instinctively envious. It is an odd combination that leads him to think very differently from, and often quite poorly of, Lucien. Not that the latter notices: it is at the moments he most reveals himself to Coffe that Lucien feels the closest to him. Stendhal provides a brilliant account of Coffe’s thoughts at these times: the more closeness Lucien assumes, the greater the distance Coffe establishes in his own mind. Already, in Le Rouge et le Noir, we were given the story of a young man, Julien, completely isolated in his childhood and desperately eager to make connections with other human beings; but Julien had endured a hard life and, whereas he hopes for closeness from others, there is almost always a distance that he himself preserves as a means of controlling the way he’s perceived: Julien is not very generous; Julien is a narcissist, at best only ever capable of fleeting moments of generosity. But Lucien has been isolated by the comfort and ease of his life – his father is a millionaire many times over. Lucien offers his friends closeness and hopes to receive it in return; he reveals himself to them and hopes to be understood; he wishes to be forgiven his good fortune, even though that good fortune has been his curse, leaving him forever in his father’s shadow. The closest he comes to receiving such understanding is from Théodelinde.

Modelled on one of the daughters of Georges Cuvier, the zoologist and naturalist, to the extent that she is impossibly tall, not particularly good-looking and therefore unmarriageable by the standards of the day, Théodelinde is in fact Clémentine Curial and Giulia Rinieri, absolutely without the possibility of sex. Fascinatingly, Bathilde de Chasteller, Lucien’s love interest, named after Clémentine’s deceased daughter Bathilde, represents both Mina de Griesheim and Métilde, with only the faintest of possibilities of sex but absolutely without the possibility of marriage.

Théodelinde is good to Lucien, and he loves her for her goodness, almost to the point of passion, which is another way of saying that he conceives for her a passionate admiration of the type that Stendhal had conceived for Giuditta Pasta. Pasta, like Gros and Destutt de Tracy before her, had found Stendhal’s esteem irksome and superfluous in some undefinable way. Did it come across as a needy invitation to reciprocate that esteem? Did it ring false, like an attempt at flattery? Stendhal never found out. But all his life, alongside a woman to love, Stendhal wanted a true friend and that friend was always most likely to be a woman. Théodelinde de Serpierre represents an effort to write that friend into existence. She does not judge, yet is endlessly perceptive. She takes everything in the spirit it is intended: ‘it was with real pleasure that he talked with Mlle Théodelinde’ (ORC, II, p. 827). She reciprocates Lucien’s affection not as a way of unburdening herself of some sort of unwanted debt, but because, instinctively, she likes him and can tell what he is thinking even when he is saying nothing or saying things he doesn’t mean. She is enormously relaxing: the sister Stendhal would have wanted Pauline to be, the sister he’d always wanted. ‘Mlle Théodelinde was his friend [. . .]; by her side, his heart found some solace’ (OI, II, p. 858). Thus it is that ‘Lucien felt for Théodelinde a form of friendship that was almost a passion’ (OC, II, p. 239).

Lucien Leuwen is also a novel about love. More than any other Stendhalian text, it is a novel about a man not knowing whether a woman loves him and about that woman not knowing whether that man loves her. Consolingly, both love each other; distressingly, neither will ever find out. It is a novel about all the strange thoughts we have when we are in love, and all the strange narratives we produce, and all the elation we experience, and all the devastating loss that then follows. Dominantly, the narrative is presented from Lucien’s tortured perspective, but every now and again, miraculously, the perspective changes to that of the otherwise largely silent Bathilde. On some level, the latter is Henriette Gagnon, in Stendhal’s patchy and largely silent recollection of her.

Lucien Leuwen is again a novel about paternity and maternity more broadly construed. Lucien is manipulated by his father, who turns out finally to be being manipulated in his turn by Lucien’s mother. Both parents are finally revealed as Wizard of Oz figures: tiny people projecting much larger versions of themselves onto their son’s sense of self. Stendhal is not here talking about his own father, so much less intelligent and plausible than François Leuwen, and still less his own mother, who never had the opportunity to truly make a mess of things. He is talking about power, always transparently patriarchal and sometimes obscurely matriarchal in its structures: the Leuwens wish to make decisions for their son, save him from himself, alter him, improve him. Freedom, Stendhal concludes, consists in not submitting to such power.

Finally, Lucien Leuwen is also a novel about empathy and narcissism. François Leuwen correctly identifies that Lucien is a dupe: that his heart is ‘constant’ and ‘all of one piece’ (ORC, II, p. 399). He therefore resolves to teach him a lesson: he bribes an ambitious married woman, Mme Grandet, with the promise of finally obtaining the political advancement she has always craved. Like Mme Roland, she hopes her husband will be appointed to high office so that she might govern in his stead. Unlike Mme Roland, she is willing to prostitute herself for this to happen. François Leuwen’s object, however, is to break his son’s heart into pieces, not with a view to distressing him – he is not a cruel man – but rather to educating him. Mme Grandet feigns love for a startled Lucien, who is taken in by her apparent sincerity. That sincerity is no more than a narcissistic projection: from his father’s perspective, sincerity can never be anything more than a narcissistic projection. Except that he makes an exception for himself and his wife: François is sincere with Mme Leuwen and vice versa. He also understands that Lucien’s own sincerity, some unconvincing moments of cynicism aside, also constitutes an exception. Ironically, at the moment when Lucien discovers how he has been mocked and betrayed and tricked, Mme Grandet is herself sincere with him – not that he notices.

Stendhal worked on Lucien Leuwen from May 1834 to 23 September 1835, when he abruptly abandoned the process of revising his completed first draft, perhaps because it suddenly occurred to him that he couldn’t publish it if he also hoped to continue serving as Louis-Philippe’s consul – the novel very plausibly directly represents Louis-Philippe as a wily old crook, doing his best to cover up the fraudulence of his power. Why this problem hadn’t struck Stendhal before is anybody’s guess. Possibly he had been overly optimistic that the riots of 1834 would lead quickly to the collapse of the regime. Possibly, he had decided simply not to think about the consequences of eventual publication – to write and be damned. What seems likely is that the new Press Laws of September 1835, in effect reversing the gains of 1830 with regard to freedom of expression and rendering the political comments in the novel potentially actionable, jolted Stendhal back to the realities of his situation. It was time to find a new project.

Immediately, he switched to the Vie de Henry Brulard: he was 52 now, even more overweight, hardly in the best of health. The opening lines of the Vie suggest that Henry decided to pick up his pen when he reached the milestone age of fifty: in Rome, looking out over all those historic buildings palimpsestically representing all the eras of the city, as a transparent metaphor for the palimpsest of memories that will constitute the story of his life – Freud would eventually use exactly the same metaphor for our retrospective explorations of the self through time.2 There’s still some life in Henry: he thinks he might have ‘imprudently’ (OI, II, p. 541) fallen in love again, just the day before writing, during a long conversation with the actress Amalia Bettini – it transpired that he had not. Mostly, however, he was conscious that his life was now behind him – hence, no doubt, his decision to have his portrait painted in 1835, twice. One portrait was formal, the other informal.

In the formal portrait, Stendhal is shown wearing a cross – he had received the letter naming him a chevalier in the Legion of Honour, pleasingly in recognition of his services to literature, on 12 February 1835. It was time to establish a final record of himself. While waiting to die, he would now give himself over less to living and loving and much more to writing, to pick up once again on the activities listed in his projected epitaphs.

Stendhal wrote the Vie de Henry Brulard in the course of some four months, between 23 November 1835 and 26 March 1836, very much for himself, not that this has stopped the book from posthumously emerging as the most important, interesting, self-aware and formally inventive literary autobiography of the French nineteenth century. It is, of course, unfinished. After abandoning his last proper attempt to write the story of his own life, Stendhal wanted to publish another big novel, to go with Le Rouge et le Noir, of which he was understandably really quite proud. He also wanted to publish something that might make him some money. Finally, he wanted to leave Civitavecchia. All these various imperatives pointed towards securing another period of leave. In February 1836 he asked the new minister of foreign affairs, the historian and political rising star Adolphe Thiers, for some time off. Permission was granted on 12 March, pending the arrival of a temporary substitute. Stendhal arrived in Paris in May 1836, having been graciously accorded three months of leave. He would stay for three years, exploiting his good relations with Thiers’ successor, Mathieu Molé, the man who had originally appointed him consul – Stendhal was becoming very adept at not turning up to work.

While in Paris, Stendhal tried to pick up again with Clémentine Curial, not that he got anywhere, her writing to him on 22 August that ‘One cannot use ashes to restart a fire, that love had died and been buried in 1826, and that he should content himself with the status of a friend’ (CG, V, p. 754).3 He also tried to seduce Mme Jules Gauthier: they had, after all, already produced a child together in the form of Lucien Leuwen. Again, he didn’t get anywhere, receiving the following rebuff, written as he stood plaintively beneath her window:

Silvestro Valeri, Stendhal, c. 1835, oil painting. This painting formerly belonged to Mérimée.

Do not regret this day, which must count as one of the finest of your life and the most glorious of mine! I feel all the calm joy of a great success: you laid excellent siege, I defended myself well, there was no surrender and no defeat, both camps emerged with glory intact. You won’t deny it, in your heart of hearts there is a satisfaction that derives from what those full of doubts such as myself call our consciences. For my part, I am happy, and yet I love you and to love is to want what I, your friend, wanted. You therefore do not want what you want, and my clever instinct has correctly guessed your virtue. Beyle, call me coarse and stupid, a cold-hearted woman, silly, timorous, idiotic, whatever you like, for insults will not efface the happiness of our divine conversation, which truly honoured our hearts, our minds, elevating us to the dignity of noble sentiments. Beyle, believe me, you are a hundred thousand times better than people think, than you think yourself, and than I thought two hours ago! Adèle (CG, V, p. 778)

Jean-Louis Ducis, Stendhal, 1835, oil painting. Stendhal is holding his favourite cane, ornamented with a gold pommel.

So instead he started writing the Mémoires sur Napoléon, his second stab at expressing himself on a subject that went beyond what could be expressed. This kept him going until the middle of 1837, when he abandoned it. He was still groping. Eventually, he hit the muddy roads of France by way of research for the Mémoires d’un touriste, nominally a species of diary kept by a pig-iron merchant travelling around the country. There was a market for this sort of thing, plus he could plagiarize Mérimée, who had already been appointed to his day job as inspector of monuments and who must have given him permission to lift material from his Notes d’un voyage dans le Midi de la France (Notes on a Journey Through the South of France, 1835), Notes d’un voyage dans l’Ouest de la France (Notes on a Journey Through the West of France, 1836) and Essai sur l’architecture religieuse (An Essay on Religious Architecture, 1837) at least, Mérimée read the Mémoires d’un touriste and raised absolutely no objections himself. Stendhal also plagiarized Aubin Louis Millin, the author of a Voyage dans les départements du Midi de la France (1807–11), who didn’t give him any kind of permission to use his work, but who had safely died in 1818 and so was in no position to complain. The political judgements cast by the Tourist are all Stendhal’s own, however:

First page of the ‘Egypt’ manuscript, part of the corpus of the Mémoires sur Napoléon, as prepared by Stendhal’s copyist and dated ‘Brumaire [18]36’ (N, p. 651).

‘As for me,’ the Tourist antiphrastically announces, ‘I consider myself to be a very sincere friend of our King’s administration and I also believe very sincerely that there’s limitless corruption. I don’t mind so much about the money: it’s the acquired habit of swindling I mind. (VF, p. 211)

The fault lies, in fact, with Napoleon, for perverting the Republic:

At the start of his reign, Bonaparte took advantage of the enthusiasm generated by the Revolution. One of his great projects was thereafter to substitute this feeling with a personal enthusiasm for him, along with vile self-interest. (VF, p. 45)

But at least Napoleon was disgusted with himself and the subjects he had corrupted, implicitly unlike Louis-Philippe, all too eager to corrupt the French people using whatever means at his disposal. The Mémoires d’un touriste contain Stendhal’s definitive political judgement on Napoleon:

beautiful took precedence over his self-interest as a king. This was quite obvious after his coup of 18 Brumaire: often, contempt would etch itself on his fine, well-formed lips, at the sight of one of his subjects, so faithful and so obsequious, pressing forward to attend him when he appeared in the mornings at Saint-Cloud. ‘This must be the price I have to pay to become emperor of the world’, he seemed to be saying to himself. And so he encouraged mediocrity. Later, when he punished the generals who still had some spirit in them, Delmas, Lecourbe, etc., and the Jacobins, his sentiments were of a different order – he was afraid. (VF, p. 262)

This, then, is the sentimental history of the ever-muddier age Stendhal had lived through: enthusiasm had turned to servility; esteem had turned to distrust and contempt; and finally everything had turned to self-interest, suspicion and fear.

Now that he was travelling along the muddy roads of France, Stendhal also felt himself ready to write about azure skies once again, translating and commenting on some of those Italian Renaissance manuscripts he had picked up in 1833, and which he now started placing in the Paris literary press as short stories. Still he was groping, but he was about to catch hold of something solid.