15

Acquisition Accounting Shenanigan No. 1: Artificially Boosting Revenue and Earnings

Acquisition Accounting Creates Distortions on the Financial Statements

One reason investors have difficulty in interpreting financial statements of acquisitive companies is because certain costs that typically should be reflected as expenses on the Income Statement are instead found on the Balance Sheet in goodwill or intangibles. Moreover, some cash outflows typically reflected as reductions in cash flow from operations are classified as investing outflows on the Statement of Cash Flows.

Thus, the first two manifestations of distortion (shifting operating costs to the Balance Sheet and shifting cash outflows from the Operations section to the Investing section) should be considered the consequence of the acquisition process, rather than an overt action by management to mislead. As such, we are not criticizing management; rather we are alerting investors to the inherently misleading information resulting from acquisition accounting conventions.

Shifting Operating Costs to the Balance Sheet

Consider two different companies in the drug industry. Company O grows organically, while Company A grows through acquisitions. Company O spends 15 percent of its $1 billion sales on R&D and charges to expense $150 million annually; in contrast, Company A spends only 3 percent of its $1 billion revenue on R&D, or a $30 million expense, as it acquires most of its new drugs through acquisitions. In comparing the results for the two companies, Company O will report a much smaller profit, as it must recognize $150 million as an expense. Company A, in contrast, would expense just the $30 million for the modest R&D spent, plus a relatively small amortization expense on the acquired intangible assets. However, over a five-year period, Company A will likely have spent much more than Company O to gain access to new drugs and to acquire entire companies. But under GAAP-based acquisition accounting conventions, most acquisition-related costs would not be expensed but rather would reside on the Balance Sheet, often with the lion’s share shown as goodwill or intangible assets.

The key point is that acquisitive companies should logically report higher profits than organic growers, simply because certain necessary costs of growing their business (like R&D) have already been incurred by someone else and thus are not be charged as an expense against revenue.

Shifting Operating Cash Outflows to the Investing Section

As we will discuss in the next chapter, the same benefit received by the acquiring company on the Income Statement can also be seen on the Statement of Cash Flows. Specifically, cash paid to access products by acquisition would be reflected as a cash outflow in the Investing (and not Operating) section of the Statement of Cash Flows. This convention under acquisition accounting rules would make M&A-driven companies appear to generate much more operating cash flow than their organic peers. Again though, the M&A-driven companies will have a much larger cash outflow because of the much higher cost they pay to acquire an entire company.

Another important anomaly relates to the cash flow generated by an M&A-driven company. Recall that increases in working capital (i.e., rising inventory or receivables) would ordinarily be reflected as a reduction in cash flow from operations. However, if that working capital came from an acquisition, rather than organically, it would be reflected as a reduction in cash flow from investing activities (and not operations). Again, the acquisition accounting conventions would allow M&A-driven companies to appear to be bigger generators of operating cash flow, but this may be a mirage. (Chapter 16 shows a variety of tricks to inflate cash flow from operations during the acquisition process.)

The Sun Will Come Out Tomorrow

One of our favorite Broadway musicals, Annie, has a memorable song, “Tomorrow,” sung by little Annie. The statement “The sun will come out tomorrow” expresses her hope for a very bright future. In much the same way, serial acquirers have mastered the art of convincing investors of a sunny future after a deal closes—no matter how cloudy the past. To increase the odds that the sun will indeed shine very brightly tomorrow on the newly merged company, the following Acquisition Accounting Shenanigans come in very handy.

The main objective in using AA Shenanigan No.1: Artificially Boosting Revenue and Earnings is to inflate the acquirer’s revenue and profits after the deal closes.

Acquisition Accounting Techniques to Artificially Boost Revenue and Earnings

1. Inflating Profits Through Tricks at a Target Company Before a Deal Closes

Think back to the important themes we discussed in Part Two, “Earnings Manipulation Shenanigans.” Unlike the first five EM shenanigans, which inflate current profits, EM Nos. 6 and 7 represent tricks to make future periods look sunny. And that’s exactly the goal of the target and acquirer: to make the postclosing period beautiful. One way to accomplish this goal is to depress earnings in the period just before the deal—called the stub period.

Watch for a Slowdown in Revenue at the Target Prior to the Acquisition Close

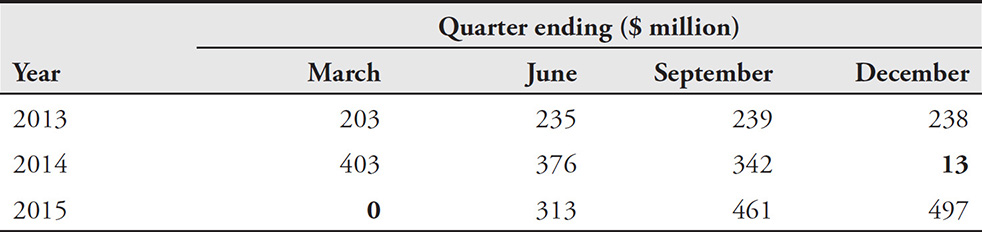

Investors in Valeant would have found a very puzzling pattern if they had paid close attention to the revenues of the company’s acquisition targets just prior to consolidation. In many of these cases, reported revenue at the target slowed down dramatically before the deal closed when compared with prior periods. No example, however, was more extreme than at Salix. Table 15-1 shows Salix’s quarterly sales from 2013, 2014, and 2015. Notice a few interesting patterns in the numbers: (1) during the last three quarters of 2013, sales were virtually unchanged; (2) during the first quarters in 2014 (when Salix management was actively shopping the company), sales grew rapidly when compared with the same prior-year periods; (3) during the last quarter of 2014 and first one of 2015 (when Valeant was in the process of closing the acquisition), sales completely dried up; and (4) the last three quarters of 2015 (after Valeant acquired Salix), sales grew dramatically.

Table 15-1 Salix Quarterly Revenue, 2013 to 2015

Let’s dig a bit deeper to make sense of these strange numbers and trends. Starting in 2014, Salix made a strong push to report terrific sales growth to maximize the price an acquirer would pay. Trying to spruce up the financial statements before a deal might be fairly common. But stuffing inventory to distributors that have no customers to buy those products goes a bit too far. Indeed, this aggressive channel stuffing caught the attention of the regulators and eventually cost the CEO and CFO their jobs.

But the accounting games were far from over. In the fourth quarter of 2014, for example, Salix reported almost no sales at all—a mere $13 million. So compared with the same quarter in 2013, sales declined an unbelievable 95 percent. How is that even possible? We can think of only two possible explanations: (1) the numbers are correct and Salix’s business had completed imploded—very unlikely, as Valeant chose not to abort the deal—or (2) the numbers are rigged and Salix had intentionally refrained from booking any business during Q4 2014 to allow Valeant to include that revenue in the periods after the deal closed on April 1.

After the deal closed, Valeant booked a whopping $1.3 billion (or $424 million per quarter) in Salix product sales over the remaining three quarters of 2015. While we claim no “smoking-gun” evidence to prove inflated revenue at Valeant from spring-loading sales, the numbers in Table 15-1 look convincing.

Watch for Unusual Sources of Revenue at the Time of an Acquisition

Agreements between two parties just before they merge clearly lack an “arm’s-length” element. Consider Krispy Kreme’s nifty scheme to inflate revenue when it was about to reacquire one of its franchises in 2003.

Before the acquisition closed, Krispy Kreme sold doughnut-making equipment to this franchise for $700,000. As part of the deal, Krispy Kreme increased the amount that it would pay to acquire the franchise by the same $700,000 to cover the price of the equipment. This arrangement clearly had no real net economic impact, so no revenue should have been recorded. Krispy Kreme, however, did not see it that way, and so it recorded the sale of equipment as revenue rather than as an offset to the increased franchise purchase price. Not surprisingly, this ruse helped Krispy Kreme maintain its streak of consistently exceeding Wall Street expectations.

Target Company Takes Large Expense Write-off During Stub Period

With the goal of deflating earnings during the stub period, companies not only refrain from reporting all their sales, but can also take big write-offs during the period. Specifically, a company might write off assets causing the stub period to be burdened with expenses that otherwise would have been charged to the newly merged company. It is simple to execute. The target company simply announces a write-off to streamline its operation in advance of the two companies merging.

2. Inflating Profits by Hiding Losses at Deal Closing

As we discussed in Chapter 6, Olympus Corporation pumped billions into money-losing investments to accelerate sluggish growth at the company. The company chose to keep the assets at full cost on the Balance Sheet, against the wishes of its auditor. As the amounts grew to an uncomfortably large amount, Olympus knew it had to find another trick to make the balance in its investment account disappear.

In October 2011 when Olympus fired its newly appointed CEO, Michael Woodford, it was revealed that the company had been operating a tobashi scheme (a scheme that makes problems “fly away,” in Japanese) in which $2 billion was said to have been siphoned off to cover bad investments made up to 20 years before.

Around 2008, Olympus had bought three companies and paid far more than they were worth, according to Woodford. This inflated price (totaling 30 percent of the deal value) was labeled “fees to a middleman.” Woodford pointed out that the cut for investment bankers typically would be 1 to 2 percent, so the $674 million paid on the $2 billion deals likely was a payment to cover losses and move the investments off the Balance Sheet to an unconsolidated related-party entity.

When Woodford, who was responsible for considerable business across Europe, noticed this shenanigan in 2008, he attempted to tender his resignation over the “strange” European acquisitions. He was given plausible reassurances and promoted to run Olympus’s entire European business. Over the next few years, Woodford was promoted to COO and eventually became the chief executive officer. As he then became aware of the true nature of these and other accounting tricks at the company, he made the board aware of his deep concerns. Unfortunately, rather than investigate the prior executives, the board fired Woodford. Shortly thereafter, the fraud was revealed.

3. Creating Dubious New Revenue Streams After Closing

Both buyers and sellers of businesses have great flexibility in structuring a deal to create dubious future revenue streams. For example, assume Buyer Ben wants to purchase Seller Sam’s business, and they come to terms on a price of $5 million, which is the fair market value of the company. Buyer Ben then says to Seller Sam, “I will instead pay you $6 million (rather than the $5 million), provided you also agree to pay me a $1 million licensing fee next year.” This change has no real economic impact to either Buyer Ben or Seller Sam, but the change in structure allows Ben to show $1 million more in revenue in the year following the acquisition. Seriously, this type of nonsense actually does happen.

Watch for Either a Buyer or Seller Creating an Unrelated Nonrecurring Revenue Stream

Occasionally, we see either a buyer or seller of a business cleverly create a recurring revenue stream by bundling a seemingly unrelated agreement into the acquisition accounting.

One clever scheme to create revenue out of thin air, using the cover of an acquisition, was employed by FPA Medical (FPAM). In 1996, FPAM paid $197 million to nursing home operator Foundation Health to purchase a group of medical practices. As part of the acquisition, however, FPAM guaranteed that Foundation’s patients would receive continued and uninterrupted access for the next 30 years. In exchange, Foundation (the seller) agreed to pay FPAM $55 million in rebates over two years. As FPAM received the $27.5 million payment each year, it recorded these amounts as sales revenue. As we thought through the essence of this transaction, we considered it quite aggressive to record any revenue for the transaction. In real economic terms, FPAM paid $197 million and received $55 million rebate over two years, resulting in a net acquisition cost of $142 million and zero revenue on this deal.

Turning the Sale of a Business into a Recurring Revenue Stream

Some companies will sell a manufacturing plant or a business unit to another company and, at the same time, enter into an agreement to buy back product from that sold business unit. Like the FPAM-Foundation deal, when cash is flowing in two directions, opportunities abound for playing games regarding how the flows are classified.

Consider the November 2006 deal between semiconductor giant Intel and fellow chip manufacturer Marvell Technology Group. Intel agreed to sell certain assets to Marvell. At the same time, Marvell agreed to purchase a minimum number of semiconductor wafers from Intel over the next two years.

In studying the footnotes to the financial statements of both companies, we learned that Intel priced this business below market value (presumably booking a smaller gain on that sale), but it was made whole as Marvell agreed to later purchase wafers at above market prices (thereby creating a new and inflated recurring revenue stream). In short, Intel used a shenanigan that resulted in shifting some of the one-time gain related to an asset sale to increase its recurring revenue from selling a product to a customer.

Question the Management of the Acquirer When Changing Accounting Practices of a Target Inflate Profits While the first AA Shenanigan showed how the target company could play games to aid the acquirer, the acquiring company still has a lot of cards it can play to inflate profits after the deal closes. Recall that in Chapter 3 we discussed the accounting change made just after Valeant acquired Medicis. In the first quarter after the deal closed, Valeant changed the revenue recognition policy for Medicis so that sales would be recognized sooner, thereby inflating Valeant’s revenue and profits. Medicis sold through its distributor, McKesson, which then sold to its customer, the physicians. Medicis historically used the more conservative “sell-through” approach, that is, booking no sales until the distributor sold to the physicians. To goose sales at the Medicis unit after the deal closed, Valeant had Medicis immediately switch to the more aggressive “sell-in” approach and started recognizing sales much earlier—when product was sent to the distributor. Not surprisingly, this brazen change in revenue recognition caught the attention of the SEC, which notified the company in a formal letter and asked it to explain any reasons for this change.

4. Inflating Profits by Releasing Suspicious Reserves Either Before or Just After Closing

During the closing process of a deal, a variety of new opportunities are created for management to provide an artificial boost to income at a later point. Management can include taking a charge for layoffs or projected legal payments and later releasing part of these reserves back into income as management deems such payments will be much less than first anticipated (the quintessential example of this shenanigan is CUC, profiled in Chapter 1). The acquirer can also set up a bigger-than-necessary reserve for contingent consideration payments that might be paid to the owners of the target company, then later release some of the reserves back into income when they are deemed unnecessary.

Releasing Deal-Related Reserves When Contingency Payments May Be Payable

Let’s assume you buy a business paying $60 million and later might have to pay an “earn-out” for as much as another $40 million if the acquired business achieves certain agreed-upon targets. That $40 million would be recorded as a “contingent consideration liability” on the Balance Sheet. Say, one year later, the business performs below expectations and the expected payout drops to $30 million. You must make an accounting entry reducing (debiting) the contingent consideration reserve and reducing (crediting) operating expenses, which results in a $10 million increase to earnings. On the face of it, the outcome seems illogical. You increase your profits when the business you bought underperforms. From an accounting perspective, however, the reduction of the future earn-out is considered a gain.

If a company wants to play games with its contingent consideration reserve, it is quite easy to do. Both inflating the initial fair market value of the total estimated payments to be made and later asserting that the acquired business is performing poorly (and little or no future payments will be made), management, like a master magician, can take out its wand and create profits out of thin air.

Watch for Big Gains from Reductions of Contingent Consideration Liability Apparel manufacturing giant Li & Fung materially boosted its operating income during the first six months of 2012 by lowering an acquisition-related contingent consideration liability from potential earn-out payments. This simple management decision resulted in a $198 million gain (51 percent of its operating profit) during the six-month period. Investors should have raised concerns about the disappointing performance of the acquired businesses, because the reduction in the contingent liability indicated that certain of the acquired businesses must have missed performance targets set by Li & Fung as of the acquisition date.

Looking Forward

Chapter 15 demonstrated how managers, under the cover of an acquisition, can cleverly inflate profits and trick investors. The following chapter shows how managers can use the acquisition structure and flexibility to inflate reported cash flow from operations.