4

Earnings Manipulation Shenanigan No. 2: Recording Bogus Revenue

The previous chapter discussed situations in which companies record revenue too soon. While this is clearly inappropriate, the acceleration of legitimate revenue is less audacious than simply making the revenue up out of thin air. This chapter describes four techniques that a company might employ to create bogus revenue and warning signs for investors to spot these nefarious shenanigans.

Techniques to Record Bogus Revenue

1. Recording Revenue from Transactions That Lack Economic Substance

Our first technique involves simply dreaming up a scheme that has the “look and feel” of a legitimate sale, yet lacks economic substance. In these transactions, the so-called customer is either under no obligation to keep or pay for the product, or no product or service was even transferred in the first place.

In his brilliant 1971 hit song, John Lennon challenged us to “imagine” a perfect world. Imagination has undoubtedly helped the world become a better place, as people’s creativity has broken boundaries and led to countless innovations. Imagination has inspired talented scientists, for example, to diagnose the unknown and find cures for diseases. Similarly, technology pioneers (like Bill Gates and Steve Jobs) imagined exciting ways to create new products, such as Microsoft’s Windows and Apple’s iPhone, that enhance our enjoyment of life.

Occasionally, though, imagination can run amok. Many corporate executives have given imagination a bad name when they’ve used theirs to get too creative with reported revenue. For example, insurance industry leader AIG imagined a perfect world for its clients (and itself), in which they would always achieve Wall Street’s earnings expectations. Imagine, AIG must have thought, how happy clients would be if they never had to experience the indignity (and stock price decline) that accompanies an earnings shortfall.

AIG and several other insurers began to market a new product called “finite insurance.” This solution would guarantee clients the ability to always produce earnings that were acceptable to Wall Street by “insuring against” earnings shortfalls. In a sense, this product was an addictive drug that allowed companies to cover up quarterly blemishes by artificially smoothing their earnings.

And not surprisingly, customers were hooked. Everybody was happy. AIG found a new revenue stream, and customers found a way to prevent earnings shortfalls. However, there was a big problem: some of these “insurance” contracts were not legitimate insurance arrangements at all; rather, they were complex and highly structured financing transactions.

How Was Finite Insurance Abused?

Let’s turn to Indiana-based wireless company Brightpoint Inc. to see how some finite insurance transactions were economically more akin to financing arrangements. It was late 1998 and the bull market was racing, but Brightpoint had a problem: earnings for the December quarter were tracking about $15 million below the guidance given to Wall Street at the beginning of the quarter. As the quarter closed, management feared that investors would be unprepared for this news and, as a result, that the firm’s stock price would be hammered.

Enter AIG and its “perfect world” products. AIG created a special $15 million “retroactive” insurance policy that would “cover” Brightpoint’s unreported losses. Here’s how the policy worked: Brightpoint agreed to pay “insurance premiums” to AIG over the next three years, and AIG agreed to pay out an “insurance recovery” of $15 million to cover any losses under the policy. This sounds like your normal insurance policy, except for one big problem: there was no transfer of risk, since the policy covered losses that had already happened. You can’t insure your house after it burns down!

Brightpoint proceeded to record the $15 million “insurance recovery” as income in the December quarter (which netted out its unreported losses). AIG recorded what amounted to bogus revenue on the insurance premiums over the next three years. Economic sense dictates that this transaction was not an insurance contract because no real risk had been transferred. Indeed, the transaction was nothing more than a financing arrangement: Brightpoint deposited cash at AIG, which AIG eventually refunded as purported “insurance claim payments.”

Regulators Considered This Scheme to Be a Scam

Brightpoint got into trouble with the SEC for inappropriately masking its problems. AIG found itself in the SEC’s crosshairs as well for knowingly structuring the insurance policy in such a way that it allowed Brightpoint to misrepresent its actual losses as “insured losses.” In November 2004, AIG agreed to pay $126 million to settle litigation with the Department of Justice and the SEC on charges that it had sold products that helped companies inflate earnings via the use of finite insurance.

Peregrine Dupes Investors with Sales That Lack Economic Substance

Creating bogus revenue from transactions that lack any economic substance extends far beyond insurance companies. Plenty of technology companies apparently got the memo of how easy it is to employ this shenanigan. Take, for instance, San Diego–based Peregrine Systems, which got busted for a massive fraud scheme that involved recognition of bogus revenue.

The SEC charged that Peregrine improperly recorded millions of dollars of revenue from nonbinding sales of software licenses to resellers. The company apparently negotiated secret side agreements that waived the resellers’ obligation to pay Peregrine, which means that revenue should not have been recorded. Employees at Peregrine had a great name for the scheme: “parking” the transaction. Sales that were near the finish line were often “parked” to help Peregrine achieve its revenue forecasts. Peregrine engaged in other deceptive practices as well to create bogus revenue, including entering reciprocal transactions in which the company essentially paid for its customers’ purchases of its software. In 2003, Peregrine restated its financial results for several earlier quarters, reducing previously reported revenue of $1.34 billion by $509 million, of which at least $259 million was reversed because the underlying transactions lacked substance.

Be Aware That with Bogus Revenue Come Those Fake Receivables

Peregrine obviously did not receive cash from customers on these nonbinding bogus revenue contracts, resulting in bogus receivables festering on the Balance Sheet. As we have learned, a rapid increase in accounts receivable is often an indication of deteriorating financial health. Peregrine knew that analysts would naturally begin questioning the “quality of earnings” if the bulging receivables balance remained stubbornly high. To avoid these questions, Peregrine played several tricks that made it seem like the receivables had been collected. These shenanigans inappropriately lowered the receivables balances, and in doing so, improperly inflated cash flow from operations (CFFO). We break down the mechanics of this chicanery and discuss Peregrine’s Cash Flow Shenanigans further in Chapter 10.

Symbol Wants in on the Action

Symbol Technologies found a creative way to recognize revenue that lacked economic substance. From late 1999 through early 2001, Symbol conspired with a South American distributor to fake more than $16 million in revenue. It instructed the distributor to submit purchase orders for random products at the end of each quarter, even though the distributor had absolutely no use for those products. Symbol never shipped the products to the distributor or any of its customers. Instead, to fool the auditors into believing that a sale had occurred, Symbol sent the products to its own warehouse in New York; however, it still retained all “risks of loss and benefits of ownership.” The distributor, naturally, did not have to pay for the warehoused product and could “return” or “exchange” the goods at no cost when it placed legitimate new orders for any product that it needed. Without a doubt, the only purpose of this charade was to give the appearance of a legitimate sale so that Symbol could record revenue.

Watch for Barter Transactions with Related Parties Investors should always be wary in seeing sales booked when no cash is paid (i.e., a barter transaction). And when such transactions are with a related-party customer, investor concerns should rise to the highest level.

Consider how D.C.-based comScore tried to cover up sluggish 2014 sales growth in its core business of selling web traffic data to advertisers. Management entered into agreements with other data providers to exchange certain “data assets.” Because no money changed hands, these transactions were disclosed and described as “nonmonetary” in its Footnotes to the Financial statements. Arrangements in which goods or services are swapped are inherently suspicious, because the amount of sales recorded for the exchange is subject to the company’s own estimate of its value, and that amount can easily be inflated, or even conjured up entirely, reflecting no real substantive economic activity.

These nonmonetary (barter) arrangements accounted for $16.3 million of total 2014 sales (5 percent of total sales), representing a big portion of comScore’s reported growth. Not only were these transactions suspicious on a stand-alone basis, but almost all (88 percent) of these barter sales were to related parties of comScore. By the third quarter of 2015 the company had already recognized $23.7 million of additional barter revenue (now representing 9 percent of total revenue). And by the end of 2015, investors had raised enough troubling questions about the true nature of these arrangements that management found it impossible to properly file its financial statements. And by failing to file, comScore was eventually delisted from the Nasdaq stock exchange.

TIP

Be extremely cautious when a company reports barter or “nonmonetary” sales, especially when the buyer is a related party.

Failing to Detect Accounting Tricks at Autonomy Costs Hewlett-Packard Billions

As Hewlett-Packard (HP) tried to jump-start its struggling business, it went shopping in October 2011 for an acquisition across the pond and paid $11.1 billion for software maker Autonomy Corporation. That turned out to be a colossal mistake; one year later, HP took an $8.8 billion impairment charge, recognizing that it had materially overpaid for Autonomy. Worse yet, HP claimed that most of this massive loss was linked to serious accounting improprieties.

When this bad news became public, not only did HP’s share price plummet 12 percent in a single day, but HP alleged that Autonomy executives had fraudulently inflated revenue to trick investors. In short, HP’s leaders claimed that they were duped by Autonomy.

The SEC investigated these allegations and concluded that Autonomy indeed used a variety of schemes to vastly overstate sales in the years prior to the acquisition. In many cases, these tricks allowed Autonomy to accelerate revenue recognition on software sales earlier in the selling process; in some cases, however, the revenue may have been completely fabricated as Autonomy was not ultimately successful in closing a deal with the end user. For example, it not only sold products to a distributor but later repurchased from that same distributor unwanted, unused, or overpriced products, initiating a “round-trip” cash payment that would come back to Autonomy. According to the SEC, this scheme alone inflated Autonomy’s reported revenue by nearly $200 million between 2009 and 2011.

2. Recording Revenue from Transactions That Lack a Reasonable Arm’s-Length Process

While recognizing that revenue on transactions that lack economic substance should never be considered legitimate, transactions that lack a reasonable arm’s-length process are sometimes appropriate. But prudent investors should bet against it. That is, most related-party transactions that lack an arm’s-length exchange produce inflated, and often phony, revenue.

Transactions Involving Sales to an Affiliated Party

If a seller and a customer are also affiliated in some other way, the quality of the seller’s recorded revenue may be suspect. For example, a sale to a vendor, relative, corporate director, majority owner, or business partner raises doubt about whether the terms of the transaction were negotiated at arm’s length. Was a discount given to the relative? Was the seller expected to make future purchases from the vendor at a discount? Were there any side agreements requiring the seller to provide a quid pro quo? A sale to an affiliated party or a strategic partner may be an entirely appropriate transaction. However, investors should always spend time scrutinizing these arrangements, as it is important to understand whether the revenue recognized is truly in line with the economic reality of the transaction.

Be Wary of Related-Party Customers and Joint Venture Partners A representative case in point is the alleged fraud at Syntax-Brillian, the Arizona-based maker of high-definition televisions. In 2007, Syntax-Brillian was flying high. Extraordinary demand in China sent sales of TVs soaring, and the start of a marketing relationship with ESPN and ABC Sports generated a buzz about its Olevia HDTVs. The company more than tripled its revenue in fiscal 2007, with sales approaching $700 million, up from less than $200 million the prior year. Yet one year later, Syntax-Brillian was bankrupt and under investigation for fraud.

Syntax-Brillian’s demise was not a surprise to investors who understood the extent to which the company’s reported results benefited from transactions with related parties. For example, the company’s staggering revenue growth came from a 10-fold increase in sales to a suspicious related party. The sales accounted for nearly half of Syntax-Brillian’s total revenue, and the related party was an Asian distributor named South China House of Technology (SCHOT). Syntax-Brillian’s relationship with SCHOT was much more incestuous than a typical customer-supplier arrangement. The two companies seemed to be involved in a tangled web of joint ventures (which also, oddly, included Syntax-Brillian’s primary supplier). Syntax-Brillian was close enough with SCHOT that it granted it 120-day payment terms and routinely extended those terms even further.

Syntax-Brillian described SCHOT as a distributor that would purchase its TVs and then resell them to retail outlets and end users in China. Many investors failed to question the company’s significant uptick in sales to SCHOT, as they believed that demand in China was high, with people upgrading their TV sets heading into the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. Investors were also cheered by reports that the Beijing Olympic Village itself was planning to fit its facilities with Olevia TVs.

Then suddenly, in February 2008, Syntax-Brillian cryptically announced that the Olympic facilities would no longer be installing the TVs that the company had “sold” to South China House of Technology. Even though Syntax-Brillian had already recorded revenue from the sale of these TVs, it agreed to “repurchase” more than 25,000 TVs for nearly $100 million. The company did not need to come up with the cash because the receivable from SCHOT was, of course, still outstanding. With this significant right of return and no receipt of cash, Syntax-Brillian should never have recognized this revenue in the first place!

Syntax-Brillian’s elaborate related-party transactions (and many other red flags, such as surging receivables) were in plain sight for any investor who read the SEC filings. Take, for example, the following reference to SCHOT found in Syntax-Brillian’s March 2006 10-Q that would have led even the most novice investor to raise questions.

Watch for Transactions with Parent Companies Consider the case of Hanergy Solar, the Chinese manufacturer of clean energy equipment (and dirty accounting tricks). In 2013, business was just starting to heat up as revenue grew 18 percent to HK$3.3 billion. The following year, revenue tripled to HK$9.6 billion. From May 2013 to May 2015, Hanergy’s stock surged 1,300 percent, bringing the total market value to a whopping HK$40 billion and making founder and chairman Li Hejun one of China’s richest men.

Digging just beneath the surface of reported revenue growth revealed a shocking fact: Hanergy’s primary customer also happened to be its majority owner, Hanergy Group Holdings (the same name was no coincidence). In 2013, 100 percent of Hanergy’s revenue came from sales to its parent company. Hanergy had other customers in 2014, but the parent still made up 61 percent of revenue. Moreover, Hanergy barely received any cash from sales to its parent, causing accounts receivable to swell to sky-high levels, resulting in DSO ballooning to 500 days at the end of 2014 (with 57 percent of its trade receivables listed as past due). Clearly, these sales were not arm’s length in nature.

By May 2015, the gig was up. One morning, when Chairman Li failed to show up for the annual meeting amid investigations of insider trading, Hanergy’s stock fell 50 percent before trading was suspended by the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

Be Alert for Suspicious Revenue from Transactions with Joint Venture Partners New York–based brand management company Iconix (ICON) was launched in 2004 by Neil Cole, younger brother of the fashion mogul Kenneth Cole. ICON had a relatively straightforward business model: purchase trademarks related to fashion brands and then license out the right to manufacture and sell clothes under these brand names. Customers generally paid ICON royalties based on a percentage of sales for each brand.

Iconix spent its first few years buying up established, but tired, fashion trademarks (such as London Fog, Joe Boxer, Starter, and Umbro). While the company may have generated a positive return on its trademark investments over time, the slow-and-steady business model failed to produce strong organic growth. To jazz up its revenue growth, management resorted to creative accounting games. One trick was to accelerate sales and earnings by carving up its trademark assets into geographic regions and selling certain ones outright. So in 2013, for example, Iconix sold its Umbro trademarks in South Korea for $10 million, recording a gain on sale for the full $10 million. Inexplicably, this gain was recorded as a component of revenue—rather than as a one-time gain from an asset sale.

In some cases, Iconix would actually create the customers that would buy these regional trademarks. In 2013, for example, it formed a 50-50 joint venture with supply-chain partner Li & Fung and transferred several trademarks to this JV. Iconix claimed not to control this JV (despite it being named Iconix SE Asia), and therefore was also able to record these trademark transfers as part of its total sales. The company disclosed in its September 2014 filing that sales to this JV alone had generated $18.7 million, which accounted for 16 percent of its total revenue for the quarter—essentially out of thin air!

3. Recording Revenue on Receipts from Non-Revenue-Producing Transactions

So far, we have addressed bogus revenue generated from transactions that are completely lacking in economic substance and ones that may have some economic substance but lack a necessary arm’s-length process. We now investigate situations in which bogus revenue arises from misclassification of cash received from non-revenue-producing activities.

Investors understand that not all cash received necessarily would be revenue or even directly pertain to the company’s core operations. Some inflows are related to financing activities (borrowing and stock issuance) and others to the sale of businesses or other assets. Companies that recognize ordinary revenue or operating income from these noncore sources should be viewed suspiciously.

Question Revenue Recorded When Cash Is Received in Lending Transactions

Never confuse money received from your friendly banker with money from a customer. A bank loan must be repaid and is considered a liability. In contrast, money received from a customer in return for a service rendered is yours to keep and should be considered revenue.

Apparently, auto parts manufacturer Delphi Corporation failed to understand the distinction between a liability and revenue. In late December 2000, Delphi took out a $200 million short-term loan, posting inventory as collateral. Rather than recording the cash received as a liability that needed to be paid back, Delphi improperly recorded it as the sale of goods—as if the inventory posted as collateral had been purchased by the bank. As you will see with Delphi in Chapter 10, not only did this twisted interpretation allow Delphi to record bogus revenue; it also provided bogus cash flow from operations.

Pay Attention to Accounting for Vendor Rebates

When purchasing goods from a vendor, cash normally flows in one direction—from the customer to the vendor. Sometimes, cash will flow in the opposite direction, usually in the form of a volume rebate or refund. Booking these cash rebates as revenue would clearly be inappropriate, as they should be considered an adjustment to the cost of inventory purchased. However, the creative folks at Sunbeam did not see it that way. Sunbeam played a neat trick to boost revenue in which it advanced cash to vendors and then recorded revenue when that cash was repaid. Additionally, Sunbeam would commit to future purchases from a particular vendor in exchange for an immediate “rebate” from that vendor, which Sunbeam, or course, recorded as revenue.

Royal Ahold, owner of U.S. supermarkets Stop & Shop and Giant, played similar games with its vendor rebates. Executives manipulated vendor accounts to create fake rebates that boosted earnings and allowed the company to reach its earnings targets. Overstated rebates totaled over $700 million in 2001 and 2002, which led to massively overstated earnings. The executives who perpetrated this scheme were ultimately found guilty of fraud and sent to prison.

Similarly, in September 2014, British grocer Tesco announced that it had overstated its profits by recording too much income related to supplier discounts and rebates. Turmoil ensued as the stock fell by over 50 percent since the beginning of the year. Tesco’s chairman, CEO, CFO, and other key executives and board members left the company. In September 2016, the U.K.’s Serious Fraud Office announced that it would prosecute three former employees for fraud and false accounting.

4. Recording Revenue from Appropriate Transactions, but at Inflated Amounts

The first three sections of this chapter focused on sources of revenue that were wholly inappropriate, as they lacked any economic substance, failed the necessary arm’s-length test, or were derived from non-revenue-producing activities. The companies profiled in this section, on the other hand, generally meet the broad guidelines for recognizing revenue. The transgression, however (and not an insignificant one), concerns recording revenue in an amount that seems excessive or misleading to investors. Excessive or misleading revenue might result from (1) using an inappropriate methodology to recognize revenue and/or (2) grossing up revenue to make a company appear much larger than it really is.

Enron Uses an Inappropriate Methodology to Recognize Revenue

As we discussed in Chapter 1, long before Enron became infamous as the “biggest accounting fraud,” for many years it operated as a small gas pipeline business in Houston, Texas. During the 1990s, the company gradually transitioned from a producer of energy to a company that facilitated trading in energy and related futures.

To understand Enron’s new business, and how it would impact the company’s reported financial statements, it’s worth considering a simple commodity brokerage transaction. Typically, if a broker facilitates a transaction with a $100 million notional value and a 1 percent commission rate, the broker would recognize just the $1 million commission as its revenue and gross profit. Enron, however, took a much more aggressive (and inappropriate) approach to recording this type of transaction. Enron would have “grossed up” this transaction by recording revenue of $101 million offset by cost of goods sold of $100 million, resulting in the same gross profit of $1 million. This uber aggressive accounting is why Enron showed the odd combination of rapidly growing revenue and puny profit margins.

A Chance Meeting with Enron CFO Andrew Fastow

So that was our working thesis for years, but we were unable to speak to senior management people to confirm this thesis because they were locked up in prison. But in December 2015, Howard’s path crossed with that of former Enron CFO Andrew Fastow, as both were invited speakers at a conference in Park City, Utah. During the Q&A of Fastow’s presentation, Howard had the opportunity to describe what he believed to be the main accounting fraud (using the same commodity example as above), and he asked Andrew whether the thesis was correct. Was Enron grossing up the notional value of a transaction and counting that amount as its revenue, rather than just counting the commission earned? His first five words to the answer were, “You are fundamentally correct, but … ,” and he then went on to describe why this underlying accounting rule was not applicable to Enron. Howard just rolled his eyes and smiled, as the thesis had been confirmed.

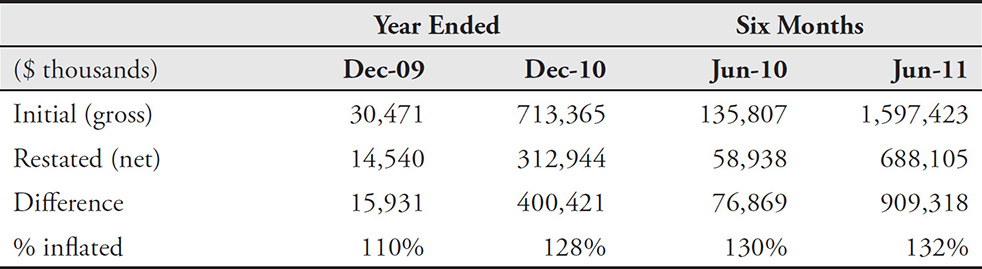

Watch for Companies Grossing Up Revenue to Appear to Be Much Larger E-commerce phenom Groupon burst onto the scene in November 2008, and only 17 months later it was privately valued at a billion dollars—the quickest that any company had reached that threshold. Then by its third birthday in November 2011, Groupon went public, raising an astonishing $700 million, becoming the second largest tech IPO at that time (after Google’s $1.7 billion raised in 2004). But before its public offering, Groupon had a tough time gaining SEC approval for its IPO, as it had to amend its registration statement eight times. The most consequential restatement pertained to Groupon’s revenue recognition, resulting in changes that sliced its revenue by over 50 percent. (See Table 4-1.)

Table 4-1 Groupon’s Gross and Net Revenue

Groupon’s main shenanigan was trying to make the business seem larger by booking as sales the gross amount its members paid for a deal, without deducting the sizable portion it owed to the merchants. In the restated registration documents (contained in Form S-1A), the SEC mandated that Groupon change from the “gross” to “net” method, causing revenue to melt down from almost $1.6 billion to only $688 million, a decline of 57 percent during the six months ended June 2011.

Surprisingly, investors seemed to ignore this very ominous development; the November IPO proved to be a major success, with Groupon’s share price jumping 31 percent on the first day traded as a public company. It closed at $26.11 on November 4 with a market value of $16 billion. But things began to unravel quickly with another (company-initiated) restatement in early 2012. And by its first anniversary in November 2012, the share price plummeted to $2.76—an astounding 90 percent decline for one of the most anticipated IPOs. Investors had seen enough, and by February 2013, CEO Andrew Mason was dismissed.

When traditional businesses migrate into e-commerce, there are often opportunities to revisit the gross vs. net revenue distinction. Take, for example, the games played by advertising agencies who began placing ads online. These companies typically record revenue for the commission fees that they earn on ads placed by their clients on television or radio spots, newspapers, or billboards. However, most agencies have approached online ads differently, electing to recognize revenue on a gross basis, thereby including the full value of the ads in reported revenue. It might seem simple enough for investors to see through this shenanigan; however, in many cases the online ad revenue is commingled with other agency fees recognized on a net basis, making it quite difficult to assess the true performance of the agency’s commissions. Since online advertising tends to grow as a share of the advertising market each year, this revenue treatment has been providing an artificial boost to reported sales growth of the agencies.

Looking Ahead

This chapter and Chapter 3 both addressed techniques for inflating revenue. These tricks included either recognizing revenue too early or recording revenue that, in whole or in part, was bogus. Chapter 5 looks at techniques for inflating income, but it moves further down the Statement of Operation. While they are not part of revenue, one-time gains may create distortions in the operating or net income of a company.