10

Cash Flow Shenanigan No. 1: Shifting Financing Cash Inflows to the Operating Section

Arnold Schwarzenegger and Danny DeVito were an unlikely pair in the 1988 hit comedy Twins. The twins were born in a genetics lab as the result of a secret experiment to create the perfect child. Doctors manipulated the fertility process to funnel the desirable traits to one child while sending the “genetic trash” to the other. In so doing, they created an intelligent Adonis (Schwarzenegger), but to do so, the doctors also had to create his gnomish, conniving twin brother (DeVito).

That very same year, new cash flow reporting standards (SFAS 95) took effect, officially formalizing the Statement of Cash Flows and its three sections (Operating, Investing, and Financing). It seems that some corporate executives were reviewing the new rules while they were watching the fertility manipulation in Twins. This may be where they got the crazy idea of manipulating the Statement of Cash Flows by sending all the desirable cash inflows to the most important section (Operating) and the unwanted cash outflows to the other sections (Investing and Financing).

In recent years, many companies have seemingly been operating their own Twins genetics labs. But rather than attempting to create the perfect child, they are attempting to create the perfect Statement of Cash Flows. In this chapter, we expose one of the most important secret procedures being performed inside those labs: shifting the desirable inflows from a financing transaction to the Operating section.

Techniques to Shift Financing Cash Inflows to the Operating Section

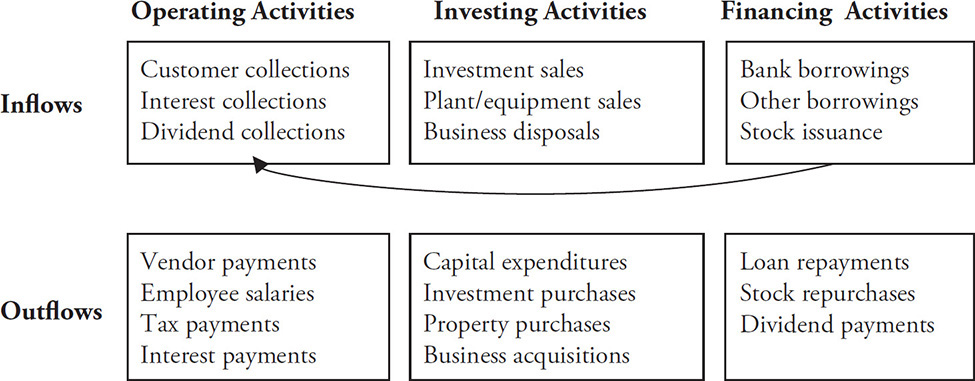

These three techniques all represent ways in which companies inflate cash flow from operations (CFFO) by shifting net cash inflows from financing arrangements to the Operating section, as illustrated in our handy cash flow map in Figure 10-1.

Figure 10-1

1. Recording Bogus CFFO from a Normal Bank Borrowing

At the end of 2000, Delphi Corporation found itself in a bind. It had been spun out from General Motors a year earlier, and management was intent on showing the company to be a strong and viable stand-alone operation. However, despite management’s ambitions, all was not well at the auto parts supplier. Since the spin-off, Delphi had cooked up many schemes to inflate its results. The auto industry was reeling, and the economy was getting worse.

Delphi’s operations continued to deteriorate in the fourth quarter of 2000, and the company was facing the prospect of having to tell investors that cash flow from operations had turned severely negative for the quarter. This would have been a devastating blow, as Delphi often highlighted its cash flow in the headline of its Earnings Releases as a key indicator of the company’s performance and its (purported) strength.

So, already knee-deep in lies, Delphi concocted another scheme to save the quarter. In the last weeks of December 2000, Delphi went to its bank (Bank One) and offered to sell it $200 million in precious metals inventory. Not surprisingly, Bank One had no interest in buying inventory. Remember, we are talking about a bank, not an auto parts manufacturer. Delphi understood this and crafted the agreement in such a way that Bank One would be able to “sell” the inventory back to Delphi a few weeks later (after year-end). In exchange for the bank’s “ownership” of the inventory for a few weeks, Delphi would buy it back at a small premium to the original sale price.

Let’s step back and think about what really happened here. The economics of this transaction should be clear to you: Delphi took out a short-term loan from Bank One. As is the case with many bank loans, Bank One required Delphi to put up collateral (in this case, the precious metals inventory) that could be seized in case Delphi decided not to pay back the loan. Delphi should have recorded the $200 million received from Bank One as a borrowing (an increase in cash flow from financing activities). As a plain vanilla loan, this transaction should have increased cash and a liability (loan payable) on Delphi’s Balance Sheet. Clearly, borrowing and later repaying the loan produces no revenue.

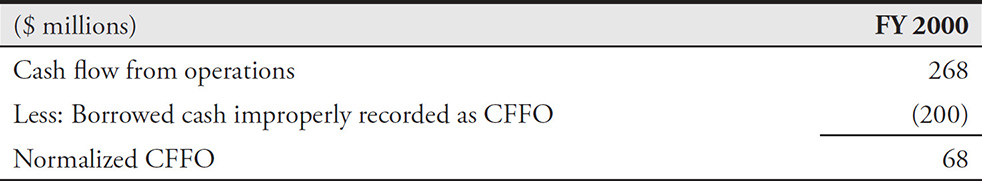

Rather than recording the transaction in a manner consistent with the economics and intent of the parties, as a loan, Delphi brazenly recorded it as the sale of $200 million in inventory. In so doing, Delphi inflated revenue and earnings, as discussed in EM Shenanigan No. 2. Moreover, it also overstated CFFO by the $200 million that Delphi claimed to have received in exchange for the “sale” of inventory. As shown in Table 10-1, without this $200 million, Delphi would have recorded only $68 million in CFFO for the entire year (rather than the $268 million reported), including a dismal negative $158 million in the fourth quarter.

Table 10-1 Delphi’s Cash Flow from Operations, Adjusted for the Impact of a Sham Loan

Remember That Bogus Revenue May Also Mean Bogus CFFO

In EM Shenanigan No. 2, we discussed techniques that companies use to record bogus revenue, including engaging in transactions that lack economic substance or that lack a reasonable arm’s-length process. Some investors become so disillusioned when they read about bogus revenue and other earnings manipulation tricks that they decide to completely ignore accrual-based numbers and, instead, blindly rely exclusively on the Statement of Cash Flows. We consider this decision unwise. Investors should understand that bogus revenue might also signal bogus CFFO. This was clearly the case in the Delphi example, as well as in many other so-called boomerang transactions. Thus, as a rule, signs of bogus revenue may portend inflated CFFO as well.

Be Wary Around Pro Forma CFFO Metrics Delphi steered investors away from its reported CFFO and instead highlighted a cash flow measure that it defined itself and confusingly labeled “Operating Cash Flow.” Normally investors use the terms “CFFO” and “operating cash flow” interchangeably; however, Delphi defined them very differently. (More on this in Part Four, “Key Metric Shenanigans.”)

In FY 2000, Delphi reported $268 million in CFFO on its Statement of Cash Flows; however, its self-defined “Operating Cash Flow” (reported in the Earnings Release) was $1.6 billion. No, we’re not kidding—a differential of an amazing $1.4 billion! Careful investors would have noticed this shenanigan and immediately become skeptical about the company, as the level of trickery was astounding and inexcusable. (Stay tuned for more on this $1.4 billion differential in Chapter 13.) Of course, even the $268 million in reported CFFO was inflated, as it included the sham sale of inventory to the bank discussed previously. The SEC must have had a field day when it sorted through all of Delphi’s schemes and charged the company with fraud.

Not only did Delphi create a misleading substitute for CFFO, but it routinely highlighted the strength of this number to investors in the title of its quarterly Earnings Releases. Investors should be cautious whenever management places such an intense focus on a company-created cash flow metric that covertly redefines the very important CFFO. Of course, management’s creative use of metrics may not always be indicative of fraud; however, investors should nonetheless ratchet up their normal level of skepticism.

Complicated Off-Balance-Sheet Structures Raise the Risk of Inflated CFFO

We have already outlined several ruses perpetrated by Enron, particularly its use of off-Balance-Sheet vehicles such as special-purpose entities. Some of the schemes that Enron concocted helped it present a misleadingly stronger CFFO. For example, Enron would create such a vehicle and then help it borrow money by cosigning its loans. The Enron-controlled vehicle then used the cash received to “purchase” commodities from Enron. Enron recorded the cash received as an Operating section inflow (CFFO) from the “sale” of the commodities.

The structure of these transactions may seem complicated, but the economics were quite simple: Enron entered arrangements to sell commodities to itself. The problem was that it recorded only half of the transaction—the part that reflected the cash inflows. Specifically, Enron recorded the “sale” of the commodities as an Operating inflow, but ignored the offsetting outflow from the vehicle’s “purchase” of these commodities. If Enron had recorded this transaction in line with its economics, the cash inflow would have been deemed a loan and hence recorded as a Financing inflow. This trick allowed Enron to embellish its CFFO by billions of dollars, to the detriment of its Financing cash flow—and, of course, of its investors.

2. Boosting CFFO by Selling Receivables Before the Collection Date

In the previous section, we discussed how Delphi and Enron created dangerous schemes in their Twins genetics labs that allowed them to record completely bogus cash flow from operations. In this section, we discuss how companies might boost CFFO with a transaction that is quite popular and considered completely appropriate: selling accounts receivable. However, the way management presents these transactions on its financial statements often leads to a great deal of confusion for investors.

Turning Receivables into Cash Even Though the Customer Has Yet to Pay

Companies often sell accounts receivable as a useful cash management strategy. These transactions are quite simple: a company wishes to collect on its receivables before they come due. The company finds a willing investor (i.e., a bank) and transfers ownership of some receivables. In return, the company pockets a cash payment for the total receivables, less a fee.

Let’s think about the underlying transaction, its purpose, and the other party’s interest. Does this arrangement sound like a financing transaction or an operating one? Many people would agree that an arrangement in which a bank simply cuts you a check looks strikingly like an old-fashioned loan—nothing more than a form of financing, particularly since management determines the timing and the amount of cash received. They therefore expect that this transaction will not affect CFFO. However, the rules state otherwise. The appropriate place to record cash generated from the sale of receivables would be an Operating inflow, not a Financing inflow. Why Operating? Because the cash received could be viewed as representing collections from past sales. Indeed, this is one of many gray areas that cause confusion among even the savviest investors.

Selling Accounts Receivable: An Unsustainable Driver of Cash Flow Growth

In 2004, pharmaceutical distributor Cardinal Health needed to generate a lot more cash. So management decided to sell accounts receivable to help the company raise cash very quickly. By the end of the second quarter (December 2004), Cardinal Health had sold $800 million in customer receivables. This transaction was the primary driver of the company’s robust $971 million in CFFO growth in December 2004 over the prior-year period.

While Cardinal Health certainly was entitled to any cash received in exchange for its accounts receivable, investors should have realized that this was an unsustainable source of CFFO growth. Cardinal Health essentially collected on receivables (from a third party, rather than from its customers) that would normally have been collected in future quarters. By collecting the cash earlier than anticipated, the company essentially shifted future-period cash inflows into the current quarter, leaving a “hole” in future-periods’ cash flow. The transfer of cash flow to an earlier period is likely to result in disappointing CFFO in the future—unless, of course, management finds another CF Shenanigan to plug the hole.

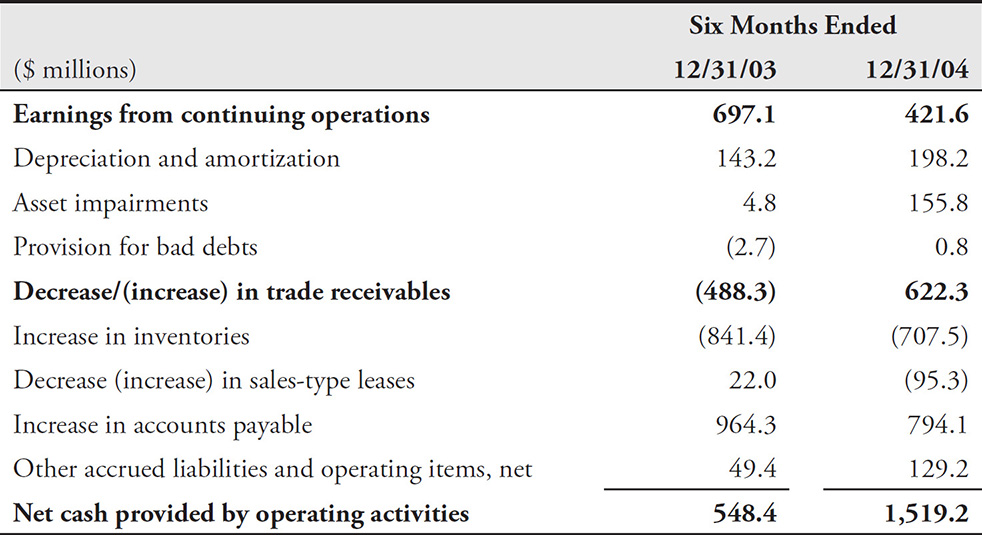

Watch for Sudden Swings on the Statement of Cash Flows Even novice investors could have identified that something important had changed in Cardinal Health’s accounts receivable and that CFFO growth was largely driven by this change. Look at the company’s Statement of Cash Flows in Table 10-2. Notice that the $971 million increase (from $548 million to $1.5 billion) in CFFO had been driven primarily by a $1.1 billion “swing” in the impact of receivables. Specifically, in the six months ending December 2004, the change in accounts receivable represented a cash inflow of $622 million, while in the previous year, the change in accounts receivable had contributed a cash outflow of $488 million. Without doubt, the massive receivable sale, not an improvement in Cardinal Health’s core business, produced the impressive CFFO improvement. To emphasize, investors should focus not only on how much CFFO grew, but also on how it grew—a very notable difference.

Table 10-2 Cardinal Health’s Cash Flow from Operations, as Reported

Sudden swings like these at Cardinal Health signal the need to explore more deeply. In this case, you would have found that the company began selling more accounts receivable. This was fairly easy to find, and the company clearly did nothing improper. In fact, the company was very forthcoming, disclosing the accounts receivable sales clearly in its Earnings Release as well as in the 10-Q filing (although disclosing it on the Statement of Cash Flows would be preferred). While perhaps casual or lazy investors were too easily impressed with Cardinal Health’s ability to grow its CFFO, savvy investors would certainly have realized that the growth came from a nonrecurring source.

Stealth Sales of Receivables

Unlike Cardinal Health, which was relatively transparent with its disclosure, some companies try hard to keep investors in the dark when their CFFO benefits from the sale of receivables. Take, for instance, the case of a certain electronics manufacturer. Sanmina-SCI Corporation reported its fourth-quarter results for September 2005 in early November. In the Earnings Release, Sanmina decided to prominently display its strong CFFO as one of its fourth-quarter “highlights.” Accounts receivable had decreased, and Sanmina also proudly pointed out the decline in receivables near the top of the release.

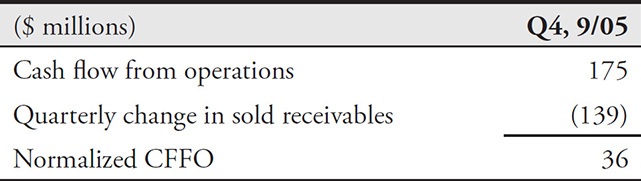

But the Earnings Release didn’t tell the whole story. Nearly two months later, deep in the 10-K filed on December 29, 2005, while many investors were on holiday, Sanmina disclosed what had really happened: the primary driver of CFFO in Q4 was the sale of receivables. Sanmina reported that $224 million in receivables that it had sold were still subject to recourse at the end of the quarter. This was quite an increase from the $84 million reported in the previous quarter. Sanmina had been quietly selling receivables for the past couple of quarters, but never at this magnitude. As shown in Table 10-3, without this increase in receivables sold, Sanmina’s CFFO would have been $139 million lower, falling to $36 million instead of the reported $175 million.

Table 10-3 Sanmina-SCI’s CFFO in Q4, 9/05, Adjusted to Remove the Impact of Sold Receivables

TIP

When normalizing CFFO to exclude the impact of sold receivables, use the change in sold receivables outstanding at the end of the quarter. In this way, you could focus on receivables outstanding last quarter but collected during this one.

Read the Quarterly Filings to Know What to Anticipate Certainly, a full reading of the 10-K would have revealed that sales of receivables drove CFFO. But could you have suspected that this was the case before the 10-K was even filed? Indeed, the answer would be yes. Astute investors would have read the previous quarter’s 10-Q and noticed that Sanmina discussed the sale of receivables no fewer than four times. They also would have noted that the company had mentioned the arrangement in passing on its earnings conference call two quarters earlier. These A-plus investors would have known that they should be wary in the fourth quarter when the CFFO suddenly surged because of a significant decline in receivables. They certainly would have been able to connect the dots.

Shun Opacity It is clearly inappropriate for companies to be opaque when reporting sensitive and impactful structured arrangements such as selling receivables. Be wary if companies fail to provide investors with details. Question their reasons for not being transparent about how they monetize their receivables. Perhaps management’s objective is simply to window-dress its Statement of Cash Flows. The worst-case scenario would be that the company is trying to hide a real cash crunch from investors. Such a cover-up clearly goes far beyond simple window dressing and points to a company camouflaging a material deterioration in its business. Dot-com high-flyer Global Crossing sold $183 million in receivables just six months before it filed for bankruptcy in 2002. Similarly, Xerox raised the ire of the SEC by silently selling $288 million in receivables at the end of 1999 to report a positive year-end cash balance of $126 million.

3. Inflating CFFO by Faking the Sale of Receivables

In the previous section, we discussed the implications of normal receivable sales for CFFO. We pointed out that in many cases, selling receivables may be not only appropriate, but also s prudent business decision. However, investors also need to understand that the cash flow that was expected in a future period has now been collected, and this inflow should be viewed as unsustainable. In this section, we take a step into more nefarious territory. We will encounter another top-secret procedure being performed in the companies’ Twins labs: faking the sale of receivables.

Sham Sales of Receivables—the “Watergate” of Shenanigans

President Nixon resigned in disgrace because of trying to cover up the break-in at the Watergate Hotel. The smoking-gun evidence apparently was included on an 18½-minute section of a White House recording that was conveniently erased to cover up the crime. Similarly, Peregrine Systems used a convenient cover-up to hide its accounting fraud. As we discussed in Chapter 4, “Earnings Manipulation Shenanigan No. 2: Recording Bogus Revenue,” Peregrine embellished its revenue in the years leading up to its 2002 bankruptcy, using deceptive practices such as recording bogus revenue and entering into reciprocal transactions. This fake revenue resulted in bloated receivables on the Balance Sheet that would never be collected. Peregrine became concerned that these bloated receivables would become the smoking gun of its bogus revenue. So the cover-up began in earnest with fake sales of accounts receivable.

In this cover-up, Peregrine transferred its receivables to a bank in exchange for cash; however, the risk of collection loss remained with Peregrine. That collection risk was huge, of course, because there were no customers—many of the related sales were bogus. Since the risk of loss had not been transferred, Peregrine remained on the hook to return the cash to the bank when the receivables inevitably were not collected.

Since the receivables had never actually been transferred, the economics of this transaction would be more akin to a collateralized loan, just as we saw with Delphi earlier in this chapter. Peregrine borrowed money from the bank and used receivables as collateral. On the Statement of Cash Flows, this should be presented as a Financing inflow. Peregrine, however, ignored the economic reality of the situation. Instead, it recorded the transaction as the sale of receivables and shamelessly reported the cash received as an Operating inflow.

Watch Carefully for Disclosure Changes in the Risk Factors Many investors overlook the “Risk Factor” section of corporate filings because it seems like legal boilerplate. Warning to investors: ignore the risk factors at your own peril. While most of the text may be similar from quarter to quarter, investors should carefully try to identify changes in the verbiage. If new risks have been added or previously listed ones have been changed, then the change is deemed worthy of disclosure by the company or its auditors, and you need to know about it.

For instance, in 2001, the year before Peregrine imploded in fraud, the company inserted an important new risk factor disclosure that should have awakened investors from their slumber. Peregrine changed its risk factor disclosure twice, first in June 2001 and then again in December 2001. The new disclosure in June 2001 informed readers that Peregrine was engaging in new customer financing arrangements, including loan financing and leasing solutions. It also reported that some customers were failing to meet their obligations. The mere fact that this disclosure found its way into the risk factors tells you it must have been significant.

Then, in December 2001, Peregrine added one small sentence to the end of the new disclosure from the June period. While it was only 12 words, it read like a five-alarm fire:

Peregrine was doing more than just finding new ways to provide its customers with financing; it was also trying to sell its accounts receivable. The cryptic nature of this new sentence, together with the hush-hush disclosure in the risk factors with no mention of it elsewhere, is extremely concerning. Peregrine was clearly hiding something big from investors and trying to comply with the minimal level of disclosure requirements.

TIP

It is well worth your time to look for changes in disclosure each quarter, particularly in the most important sections of the filings. Most research platforms and word processing software have “word compare” or “blackline” functionality. Reviewing both filings side by side is not as cumbersome as it sounds.

Computer Associates Makes an Accounting “Decision”

Computer Associates’ 2000 10-K revealed that one of its primary sources of operating cash flow that year had come from its fourth quarter “decision” to assign accounts receivable to a third party. No other details were provided. Investors were given no insight into the details of the arrangement, the mechanics of the “assignment,” or the magnitude of the impact.

Recall from Chapter 3, “Earnings Manipulation Shenanigan No. 1: Recording Revenue Too Soon,” that the SEC charged Computer Associates (CA) with prematurely recognizing more than $3.3 billion in revenue from 1998 to 2000. Well, like Peregrine, CA needed a cover-up to conceal this bogus revenue. CA found one by offloading receivables, and the company seemed to try to keep that transfer under wraps. Whenever companies disclose that a mysterious new arrangement is a driver of CFFO (or of any important metric, for that matter), investors should seek to understand the mechanics of the arrangement. Only significant changes would require new disclosure, so when you notice something new, consider it a big deal. At the benign end of the spectrum, it may simply be a nonrecurring benefit that might be important to your analysis. However, on the other end of the spectrum (think CA), it may be a red flag signaling a major impropriety.

Recourse or Nonrecourse?

When a company sells its accounts receivable, it typically it does so under a “nonrecourse” arrangement, which means that the risks of customer default are passed on to the buyer (usually a financial institution). In cases where receivables are sold on a “nonrecourse” basis, the cash received is treated as an Operating cash inflow. By contrast, in cases when the seller retains some of the credit risk (“recourse”), the transaction is considered a form of borrowing, and the cash received is classified as a Financing inflow, with no impact on operating cash flow. In these recourse arrangements, Operating cash flow and free cash flow should be unaffected.

Sometimes companies get confused and include cash received as part of cash flow from operations even though credit risks remain and the proper categorization should be in the Financing section. That was the case with Zoomlion, a Chinese manufacturer of construction equipment, when the company claimed to have sold accounts receivables on a nonrecourse basis (thus including the RMB5.2 billion proceeds as part of the operating cash flow), when in fact it still retained some credit risk. Specifically, astute analysts would have noticed that Zoomlion disclosed its obligation to repurchase equipment from financial institutions that repossess equipment as a result of customer defaults. (See the footnote below contained in the company’s 2014 Annual Report.) Even though Zoomlion is not directly on the hook for bad debts, the repurchase commitment mandated that the company provide cash should the debts go bad. In our view, this is tantamount to providing recourse, only in a more convoluted way.

Looking Ahead

A second clever way in which management may inflate operating cash flows is by pushing some of the “bad stuff” (i.e., the outflows) from the Operating section to another place on the Statement of Cash Flows. The next chapter shows just how easy it is to move these outflows to the less-scrutinized Investing section.