3 Flat Cat Canyon

SCENERY:

DIFFICULTY:

TRAIL CONDITION:

SOLITUDE:

CHILDREN: NOT RECOMMENDED

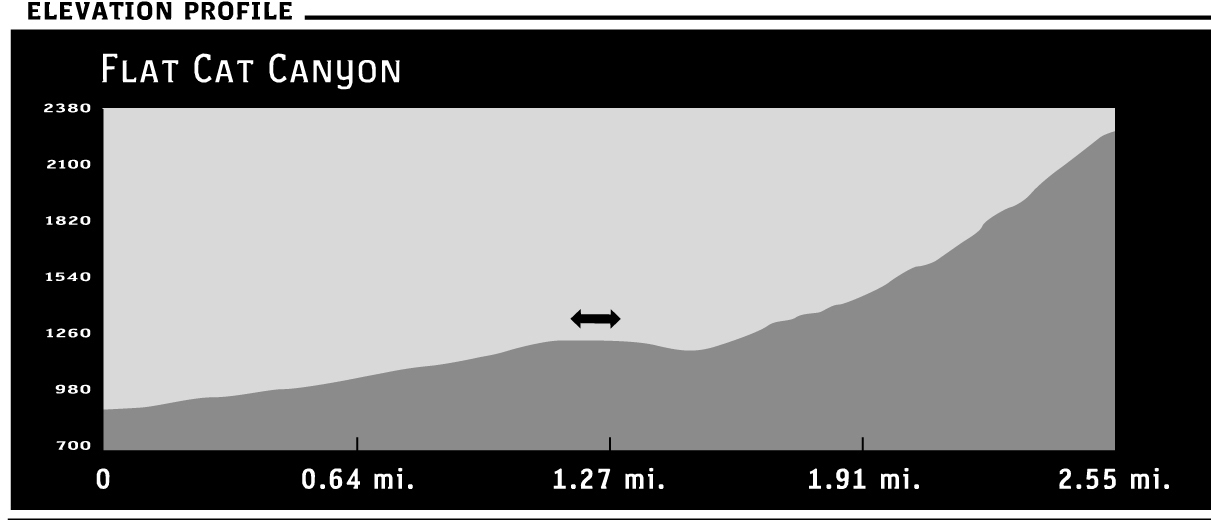

DISTANCE: 5 miles round trip

HIKING TIME: 6–7 hours

OUTSTANDING FEATURES: Desert flowers, rock formations, expansive view of the desert valley, palm oasis, and trickling water

This extreme trek up a densely vegetated, boulder-populated ravine offers a sense of accomplishment at hike’s end. But expect a tough climb, eking out a route as you scale boulders toward a hidden palm oasis at 2,500 feet (a 1,700-foot elevation gain). Don’t attempt this hike unless you’re experienced and physically prepared for a tough challenge; also, make sure you have plenty of water and lots of time for a slow, grueling pace. Ravine temperatures can drop significantly from those on the desert floor, so wear layers to escape a chill. Also consider a double layer of pants to protect your skin from tangles with prevalent and unforgiving acacia catclaw. And be aware of any expected bad weather—you don’t want to get caught in this steep canyon ravine in storms and flooding.

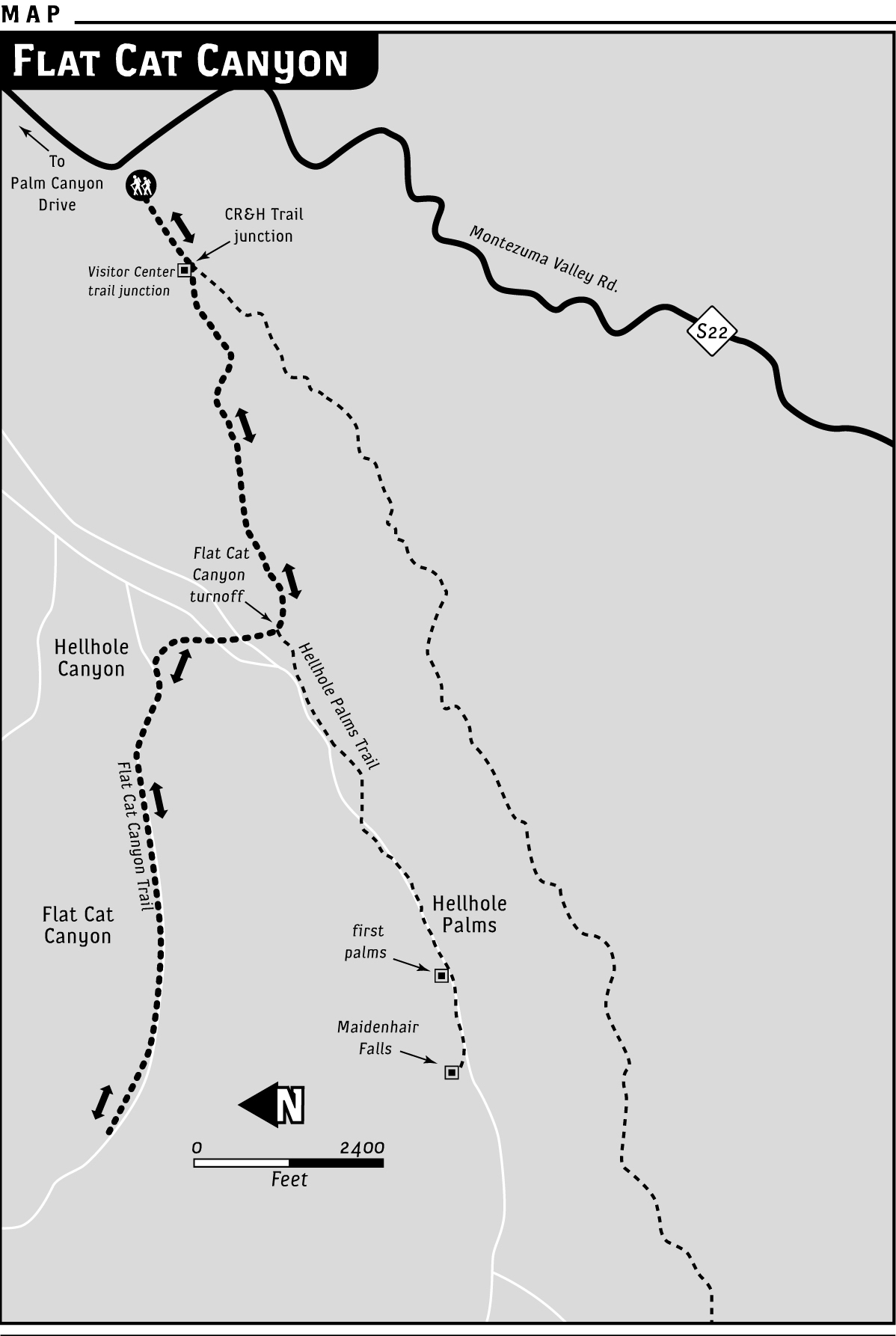

Directions: From Interstate 15, take the Pala–Highway 76 Exit and drive east for 33.6 miles to CA 79. Turn left, traveling 4.1 miles to County Route S2, where you’ll turn right and drive another 4.6 miles to CR S22–Montezuma Valley Road (commonly called the Montezuma Highway). Turn left. Drive approximately 14 miles to the trailhead on the left, which sits almost 1 mile above the Visitor Center.

| GPS Coordinates | 3 FLAT CAT CANYON | |

| UTM Zone (WGS84) | 11S | |

| Easting | 555319 | |

| Northing | 367893 | |

| Latitude–Longitude | N 33º 14’ 52.8130” | |

| W 116º 24’ 22.1743” |

From the trailhead staging area, move generally southwest toward the mountains on the Hellhole Canyon Trail (see Hellhole Canyon to Maidenhair Falls). After 1.2 miles, head north on the flat path, away from Hellhole Canyon. Move toward the narrower, adjacent (to the north) canyon; this is Flat Cat Canyon, named for a dead “flat” bobcat found by rangers in a cavern near the top many years ago.

From the trailhead staging area, move generally southwest toward the mountains on the Hellhole Canyon Trail (see Hellhole Canyon to Maidenhair Falls). After 1.2 miles, head north on the flat path, away from Hellhole Canyon. Move toward the narrower, adjacent (to the north) canyon; this is Flat Cat Canyon, named for a dead “flat” bobcat found by rangers in a cavern near the top many years ago.

At first, this less-defined route may make you feel as if you’re cutting aimlessly across open desert. Don’t worry—you haven’t fallen down Alice’s rabbit hole, though you may glimpse the long ears of a jackrabbit loping among the cholla cacti and the silver-green mounds of chuparosa. Also watch for small, shallow depressions in the sand. These are the dusty “tubs” made by kangaroo rats that roll in the sand to bathe.

Cut across a sand wash channeled out by floodwaters, and turn to the right for a short distance. Tracks are usually plentiful in this area. You’re likely to see the hoof prints of bighorn sheep, along with coyote and fox tracks, which are difficult to tell apart. A coyote’s claws are usually more defined on imprint than a fox’s.

The (southern) ridge of Flat Cat Canyon will be on your left. At its rocky endpoint, take a look at the interesting metamorphic rock that looks like enormously magnified phyllo dough, its many layers baked a deep brown. Head north again for a short distance, then southwest into the ravine’s opening. The trail will be what you make of it at first, picking your way through cacti and rocks.

Generally, the best way to start heading up the ravine is on the right, where a gently ascending sand wash makes for fairly easy stepping (heading more to the left requires more-difficult rock scrambling).

Watch for birds’ nests in the spindly trees and bushes (acacia, palo verde, creosote). The verdin, a small, yellow-capped bird native to the desert, builds a globed nest with an opening near the bottom. On outer tree limbs you may see a few nests in close succession; the male verdin builds several of them so his mate can choose the one in which they’ll raise their young.

Also look for spring flowers, sometimes blooming even in fall and winter after rains. Dark-purple desert Canterbury bells bear yellow stamens. Bright desert gold poppies rise from fringelike leaves. Magenta-pink monkey flowers with darker magenta markings and gold-yellow stamens provide low-growing splashes of color.

A few stands of boulders that you can step over give way to less readily scaled ones. As the hike progresses, you’ll be required to puzzle out the best handholds and steps to ascend the canyon. Among increasing boulder problems and nasty tangles of catclaw bushes, the route is slow going. You’ll see the leavings of canyon-dwelling wood rats near rock crevices. The piled deposits of elongated oval droppings are called “middens,” although the creatures themselves remain unseen.

A nice little ledge about 1.75 miles from the trailhead is a good place to pause and gaze down at your progress thus far. The desert valley is distant, the cars moving along Montezuma Valley Road almost soundless from this vantage point. Perhaps stop to rest and have a drink or snack. You’ll hear and see hummingbirds. Ravens fly overhead, and you might spot quail. With binoculars, take in close-up views of the rocky ridges on either side of the canyon. You might get lucky and spot a group of well-camouflaged bighorns resting on a rocky ledge.

The next 0.25 miles or so is difficult terrain. Moving to the left side of the gorge is a little easier going at this point—easy being a relative term on this challenging hike. Once you scale a couple of difficult boulder sets, you’ll come to a flat, open area. The terrain lasts only about 60 yards, so savor the moment. Be sure to look up into the ravine. This is your first opportunity to spot the palm oasis peeping into view. Tired and sweaty, you may have begun to doubt its existence. Spotting those palm fronds peeking above a boulder may feel like finding buried treasure, or how Columbus must have felt upon finally spotting land. Even for the most experienced, this extreme hike is a challenging adventure.

Only a little more than 0.5 miles remain to reach the palms, but don’t get too confident (and possibly careless). Quite a few demanding boulder puzzles remain. Moving steadily, you’ll need 40 minutes or more to reach the first palm tree.

Staying left remains the easier route. Past the first palm, work your way down into the center of the narrow canyon. From there, you’ll reach several more palms, where water trickles around and over rocks. Be careful, watching every step. A pile of jumbled rocks forms a cavernlike space here. Before realizing it, you may find yourself stepping over its top. Fallen palm fronds don’t provide solid footing, and spaces between the rocks could easily allow a foot to slip through, causing injury.

You can continue a little farther to the largest grove of palms if you’re up to more exertion, or finish the hike in the shade near any one of the smaller groupings. A vee of light-revealing sky above the desert valley is your view from the dim shade of the oasis.

The canyon towhee (a grayish-brown bird with reddish underside highlights) may hop close, curious to have a look at the new visitors. The perky bird’s wings taunt you as it flits away. Contemplating the trip down, you may wish you could sprout a set of wings yourself—for an easy descent. Be sure to give yourself plenty of time (two and a half to three more hours) for the return trip.