4

4

In which Colonel James Drax holds a feast at his sugar plantation on the island of Barbados (1640s)

How the West Indian sugar islands drove the growth of the First British Empire

When Colonel James Drax, the first sugar baron in the English West Indies, slaughtered one of his cattle, he would invite his fellow planters on the island of Barbados to a lavish entertainment. Richard Ligon, the manager at another early sugar plantation, attended one of these occasions and described the splendid feast. The first course was an extravaganza of more than a dozen different beef dishes, from boiled rump and marrow bones to pies of minced tripe and tongue seasoned with sweet herbs, suet, spice and currants. Among them was also an olio podrido, a highly spiced Iberian beef stew. The second course included more beef dishes as well as Scottish-style collops of pork; boiled chickens; shoulder of goat dressed with blood and thyme; a loin of veal cooked with oranges, lemons and limes; suckling pig in a brain and claret-wine sauce seasoned with salt, sage and nutmeg; as well as rabbits, pigeons, turkeys, capons, fat hens, and two Muscovy ducks larded and well seasoned with salt and pepper.1

The third course consisted of an array of imported delicacies such as Westphalia hams and dried beef tongue; pickled oysters and caviar; anchovies and olives; and ‘Virginia Botargo’, a fish roe relish, which Ligon thought was the best he had ever tasted. Sweet dishes of custards and creams were dotted among the savoury specialities, including pastry puffs made with imported English flour. Baskets filled with fruit also delighted Ligon, especially the pineapples then virtually unknown in England, which he regarded as so delicious they were ‘worth all that went before’.2 The bewildering array of food was complemented by an equally lavish choice of drinks: mobbie, distilled from sweet potatoes; perino, made from cassava; imported French brandy; Madeira, Rhenish wines and sack; and the ‘infinitely strong’ Kill-Devil: rum made from the ‘skimmings of the Coppers that boil the Sugar’.3

Drax lived like a prince in the Jacobean mansion he had built on his plantation. The wealthiest man on Barbados, he entertained according to seventeenth-century aristocratic ideals of hospitality and sociability. But it was no easy feat to emulate the English aristocracy on a country estate thousands of miles from London. The European delicacies he served had weathered an arduous journey to reach his table, first crossing the Atlantic in the hold of a ship and then carried from the port of Bridgetown ‘upon Negroes’ backs’ up and down steep gullies to reach Drax’s inland plantation, which was inaccessible by cart. And this had to be done at night so that the heat of the sun did not spoil the comestibles.5 On an island where beef was rarely eaten, since cattle were too valuable as draught animals, only Drax could afford to set aside animals to raise for meat, and reserve as pasture land that might otherwise have been used to grow sugar. On Barbados this feast centred around dishes of beef was fabulously extravagant.

It was something of an honour for Richard Ligon to be invited, as he occupied a delicate social position, somewhere between friend and socially inferior employee. He worked on a neighbouring sugar plantation as secretary, adviser and occasional overseer. During the English Civil War he had fought alongside the owner, Sir Thomas Modyford, in the royalist Exeter garrison. Although he was allowed to go free when the city finally fell to parliamentary forces, he found himself ‘destitute of subsistence’ and ‘a stranger in my own Country’ now that England was a Protestant Commonwealth.6 At the age of 60, Ligon was rather old for a colonial venture, but he decided to try his luck with Modyford’s party of royalist refugees, who initially planned to set up a sugar plantation on the island of Antigua. But with the loss of one of the ships on the voyage out, Modyford’s plans changed and he decided to stop in Barbados, where he bought into an established sugar plantation owned by Major William Hilliard, who was keen to leave its running to a partner while he returned home to ‘suck in some of the sweet air of England’.7

Ligon’s arrival in Barbados in 1647 coincided with the moment of the island’s transition from a nondescript English settlement into the wealthiest plantation in the British Empire. It far outshone the Munster Plantation, which occupied this position in the 1630s. In the account of his experiences–A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados (1657), written in a debtors’ prison on his return to England–Ligon described how the introduction of sugar transformed the island. Land prices skyrocketed. Colonel Modyford paid £7,000 for his half-share in Hilliard’s 500-acre sugar plantation, which had cost only £400 five or six years previously, when tobacco and cotton were the island’s main crops. Ligon correctly predicted that once all the small plantations of 20 or 30 acres not large enough to embark on the capital-intensive project of growing sugar had been amalgamated into large plantations, this tiny Caribbean island, not much bigger than the Isle of Wight, would become ‘one of the richest Spots of earth under the Sun’.8

Captain John Powell claimed the uninhabited island of Barbados for the English when sailing home from South America in 1625 on a voyage undertaken on behalf of the Courteen textile trading company. He erected a cross and inscribed the name of the English king on a tree. With William Courteen’s financial support he returned two years later, accompanied by his brother, Henry Powell, and 50 hopeful settlers; among them was the 18-year-old James Drax.9 The new colony was planted just as English attitudes towards empire were changing. By the 1620s, Virginia was sending 200,000 lb of tobacco a year to England, where sales were booming, and one pound of the weed could fetch as much as £1.10 This was evidence that a colony reliant on an agricultural cash crop could be worthwhile. Henry Powell left the men to construct a makeshift initial settlement and set sail for Dutch Guiana, from where he returned with food, tobacco plants and seeds, as well as three canoe-loads of Arawak Indians. With the help of the Arawaks, on whose agricultural knowledge the settlers depended, the Englishmen hoped to emulate the success of Virginian tobacco planters.11

One of the settlers was 19-year-old Henry Winthrop. He optimistically promised his father John in England that, in return for two or three servants a year plus supplies, he would send back 500–1,000 lb of tobacco. But Henry’s crop was a disappointment. His father complained that it was ‘very ill conditioned, foul, full of stalks and evil coloured’. He was only able to sell it for pennies rather than shillings per pound, and he warned Henry that, given that he had to provide for his other children, he would not be able to send him further assistance. By the time John’s admonitory letter arrived in Barbados, Henry was already on his way home and ready to try another colonial venture; three years later, he would join his father on his founding voyage to Massachusetts Bay.16

Unlike Winthrop, Drax managed to make some profit from his tobacco, and this allowed him to begin buying up more land and servants to work it.17 Nevertheless, Barbadian tobacco was of poor quality, and when in 1630 the market price of even the superior Virginian product fell to a tenth of its previous value, it became clear that the crop was never going to make the Barbadian planters’ fortunes. They experimented with cotton, ginger, indigo and fustic wood (which produced a yellow dye). Drax, Hilliard and another of the first settlers, James Holdip, used their tobacco profits to move into cotton. They acquired plants and know-how from the Dutch, who dominated Caribbean trade in the 1630s. At first cotton did well. New settlers were attracted to the island and its population grew sevenfold. But at the end of the decade, the value of cotton and indigo declined as the market became saturated. The three men cast around looking for a new crop, and sugar caught their attention.18

In the 1630s, the north-eastern coast of Brazil was the global hub of sugar production. The world centre of sugar manufacture had gradually moved from northern India to the Levant in the early medieval period, and by the fifteenth century Cyprus and Sicily were Europe’s main suppliers. But when the Portuguese discovered the Azores in 1427 and Madeira in 1455, they found that the climate of these Atlantic islands was better suited to growing sugar than the Mediterranean, and when they took Brazil in the 1540s, they expanded production into their new colony.19 One hundred years later, as Portugal’s position as the pre-eminent European maritime power was on the wane, the Dutch West India Company seized control of the Brazilian sugar plantations as well as Portugal’s slave-trading forts dotted along the West African coastline. Dutch vessels now criss-crossed the Atlantic Ocean, bringing African slaves to work on the plantations, and returning laden down with huge cargoes of sugar destined for Antwerp’s refineries. Drax and his associates would have been aware of this trade, and it was reportedly a Dutch visitor to Barbados who persuaded him and some other planters to try their hands at cultivating this potentially lucrative crop.20

Drax visited Brazil in 1640, almost certainly to learn how to cultivate and process sugar cane. Yet when Ligon arrived on Barbados seven years later, sugar planting was still ‘in its infancy’.21 Initially the sugar that Drax, Holdip and Hilliard were producing was wet with molasses and of little worth. However, by the time of Ligon’s departure in 1650, they had mastered the art. They had learned that the canes needed to be planted close together so as to hinder the growth of the vigorous vines that would otherwise wind their way up the young plants and kill them.22 They had worked out that they had to wait 15 rather than 12 months for the cane to ripen, and that in order to prevent bottlenecks at the mill it needed to be planted at intervals so that it matured on a rolling schedule. For once cut, the cane could only be left two days before it soured and spoilt the entire batch of juice.23

If the Newfoundland fisheries were pioneering in their industrial scale and organisation, the West Indian sugar plantations were the world’s first agro-industrial factories where the human needs of the workforce were subordinated to the demands of production. Rather than adopting the Portuguese system whereby wealthy planters built a sugar mill and were supplied with cane by sharecroppers, Drax emulated the more efficient Dutch factory-plantation units, which controlled every aspect of the process from cultivation to refining.24 Industrial principles of the division of labour were even applied in the fields, where the workers were separated into specialised planting, weeding and cutting gangs. The careful timing required for the harvesting and grinding of the cane meant that the cutters had to synchronise their efforts with those of the men working on the mill who fed the canes through its immense rollers (turned by five or six oxen) to press out the juice. The system reduced the workers to the role of mechanical parts in a larger machine. Even the mules, carrying the canes from the fields to the rollers, became automatons, plodding backwards and forwards without need of human guides.25

The boiling houses where the juice was crystallised into sugar prefigured by more than a hundred years the factory floors of the textile mills. The slaves were organised into shifts so that there was no break in the production process. Ligon described how the work went on from ‘Monday morning at one o’clock, till Saturday night… all hours of the day and night, with fresh supplies of Men, Horses and Cattle’.26 As with the grinding of the canes, timing was crucial. Once squeezed out of the canes, the juice was channelled into a cistern where it could not remain for more than a day, otherwise it soured. From the cistern it passed through five enormous heated coppers, constantly surrounded by gangs of men who stirred and skimmed the bubbling juice. A lime temper made of ash and water was added to the last four coppers to aid the crystallisation process. The men working around the final copper had the skilled job of catching the moment when the sugar reached crystallisation point. They would then quickly pour in two spoonfuls of salad oil and hurriedly ladle the juice into the cooling cistern without allowing the copper–still over the furnace–to catch and burn as it was emptied.27

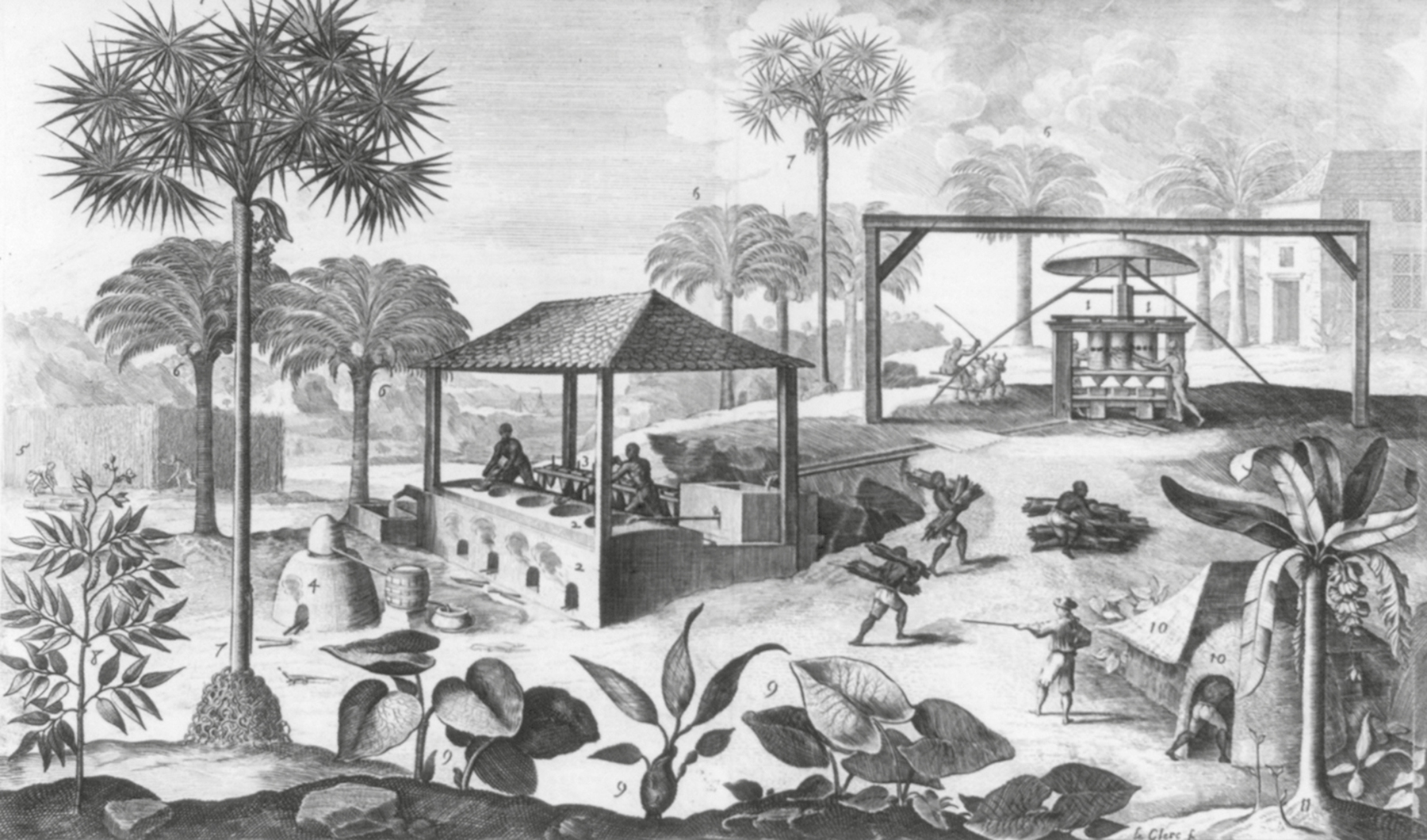

A view of an early West Indian sugar mill and boiling house. This picturesque depiction with its focus in the foreground on West Indian foliage and a quaint slave hut would appear to belie the brutality of the first agro-industrial enterprises if it were not for the menacing figure of the white overseer supervising the slaves carrying sugar cane up to the ox-powered mill.

The acute time-sensitivity of the process, the need for discipline and careful organisation, the bringing of field and factory together in one place and the fact that the planter owned all the capital assets from land to labour to processing plant–and could therefore take all the profit–made the sugar plantation a manifestation of capitalism in its hitherto most rapacious form. The plantations were agro-industrial complexes far in advance of farms and industries in Europe.28 The sickly miasma that enveloped the sugar works foreshadowed the pall of smoke that would hang over the dark satanic mills of England’s Industrial Revolution.

‘I never more will drink Sugar in my Tea, for it is nothing but Negroe’s blood,’ wrote the ship’s purser Aaron Thomas in his sea diary at the end of the eighteenth century.29 When his frigate took part in an expedition to the West Indies, he was shocked to see how sugar was made. But in the early years of sugar production it was as much white men’s blood as it was Africans’. Barbadian planters used white indentured servants to do the hard work of clearing the virgin forest and cultivating and processing their first crops.

In the century between 1530 and 1630, about half the rural peasantry in England were pushed off the land by agricultural improvement.30 Some acquired new skills and found work as artisans, others were able to hire themselves out as labourers on the enclosed estates, but by the 1620s, large numbers of landless labourers roamed the countryside looking for work.31 The American colonies took advantage of this to secure a labour force for their short-staffed plantations. English merchants would recruit young men and women from the rural poor and transport them across the Atlantic, where they were sold to a planter for a fixed period, normally four to five years. At the end of their term, they were promised a one-off payment of £10 to use to set themselves up in the New World.

Advocates of indenture saw it as a safety valve, ridding the English countryside of a potentially insurrectionary vagrant population and putting them to useful work producing tropical agricultural commodities.32 Indentured labour was a form of temporary slavery, as servants were bought and sold and were powerless to renegotiate the terms of their contract with masters who frequently abused their position of power.33 The planters did not feel the sense of paternal responsibility for their workers that, at least theoretically, ameliorated the position of English agricultural labourers. They viewed indentured servants as chattels, and, indeed, referred to these men and women as ‘white slaves’.34 The Cromwellian state made good use of the system: it ‘Barbadosed’ 12,000 Irish rebels and royalists, transporting them into servitude in the West Indies, whence they were forbidden to return.35 Seventeenth-century planters did not suffer from the racial delusion (which developed later) that white men were unfit for hard labour in the tropics. Cromwell’s political prisoners found themselves ‘grinding at the mills, attending the furnaces, digging in this scorching land… cutting, weeding, and hoeing’.36

Despite the arrival of at least 8,000 white servants on Barbados in the 1640s, the demand for workers on the labour-intensive sugar plantations was insatiable. When the first slave-trading ship to visit the island sailed into Bridgetown harbour in 1641 carrying hundreds of enslaved West Africans, they were eagerly bought up by the wealthier planters. More slave ships soon followed.37 African slaves were more expensive than indentured labourers–a healthy African cost between £25 and £30 compared to £12 for an indentured servant–but the large planters’ sugar profits enabled them to make the long-term investment in workers they would own in perpetuity.38 After a five-month trip to the West Indies in 1645, George Downing, a ship’s chaplain, wrote to his uncle, John Winthrop (by then established as governor of Massachusetts), to explain how a planter might get started with indentured servants, but once he had earned enough, he would procure ‘Negroes’ upon whom the return on investment was excellent: ‘The more [Africans] they buie, the better able they are to buye, for in a yeare and halfe they will earne (with gods blessing) as much as they cost.’39 By 1660, there were around 20,000 enslaved Africans on Barbados.40 The appalling working conditions, malnutrition and disease led to such a high mortality rate among the slaves that in 1688, English sugar islands needed 20,000 new slaves a year just to maintain their labour force.41 This constant demand for new workers for the sugar plantations stimulated the growth of the English slave trade.

Over time, slave labour came to dominate, but at first African slaves and indentured servants worked as cogs in the wheels of the sugar machine alongside each other, manuring the fields, digging trenches, trashing and cutting the cane, passing it through the mill and boiling the sugar. It was gruelling and dangerous labour. The cane subjected the workers to numerous painful and easily infected leaf cuts; many lost limbs when they were pulled into the rollers by accident, or were badly scalded by boiling sugar juice. Subject to brutal floggings and cruel punishments for minor indiscretions, they lived ‘wearisome and miserable lives’.42 If they got wet working in the field, they had nothing to change into as they were provided with only one set of clothes. They slept on bare boards, and while their masters gorged on boiled rump steak and marrow bones, the indentured labourers and slaves regarded the skin and entrails of the oxen as a high feast.43 Their staple food was spoiled Newfoundland salt fish and loblolly, a cornflour gruel they detested.44 If a slave resorted to stealing food, a common punishment was to string him up on a gibbet with a loaf of bread hung just out of reach for him to contemplate while he starved to death.45

Meanwhile, on the back of the slaves’ labour, the planters grew rich. Once the sugar juice had passed through the boiling house, it was poured into conical pots and left in a still-house for a month. Liquid molasses slowly drained out of the pots, leaving behind soft, dry brown muscovado sugar. This was packed into bales and carried by mules down to storehouses in Bridgetown to await the arrival of a European ship to take it to the London refineries.46 Sugar planting required patience–it took 22 months from planting the cane until it was transformed into saleable sugar–but it was worth the wait. Drax calculated that his first crop of good-quality sugar, which sold at £5 per hundredweight on the London market, increased his income per acre fourfold.47 Those who had the capital to invest in land, labour and equipment followed Drax’s lead, and within a couple of decades they had stripped Barbados of its forests and replaced them with a sugar monoculture.48 Industrial economies of scale applied to sugar planting–contemporaries calculated that a planter needed at least 200 acres of sugar cane to clear a profit after the expensive investment necessary to set up a mill and a boiling house–and so by 1650, land on the island was concentrated in the hands of a tiny elite of fewer than 300 planters.49 In the last two years of the 1640s, Barbados exported sugar worth over £3 million, catapulting it into the position of England’s richest colony and making its planters as wealthy as aristocrats.50

Colonial trade–and especially the trade with the West Indian sugar islands–had a profound economic, political and social impact on seventeenth-century England. New World goods required further processing when they arrived at the ports. Tobacco had to be cured and rolled and muscovado sugar refined into white lump sugar. Sugar bakeries, as the refineries were known, sprang up in London and ports around the country. In 1692, there were 19 in the City and another 19 in Southwark, contributing to the great clouds of smoke hanging over London.51 These promoted subsidiary industries supplying them with coppers and mining the coal to fire the furnaces.52 But the requirements of the English refineries were nothing compared to the demands arising from Barbados. The deforestation of the island to make way for sugar cane meant that all the coal to fuel the furnaces that heated the coppers had to be imported from England.53

Thomas Dalby, who wished to demonstrate the financial and commercial benefits of the West Indian colonies to the British Isles, listed the many other manufactures besides coppers and mills needed by the planters. ‘All their Powder, Cannon, Swords, guns, Pikes, and other Weapons… Axes, Hoes, Saws, Rollers, Shovells, Knives, Nails and other Iron Instruments… Sadles, Bridles, Coaches… their Pewter, Brass, Copper and Iron Vessells and Instruments, their Sail-Cloath, and Cordage… all which are made in and sent from England.’54 He claimed that every ‘White Man, Woman, and Child, residing in the Sugar-Plantations, occasions the Consumption of more of our Native Commodities, and manufactures than ten at home do’.55 England and Ireland supplied the plantations with ‘great quantity of Beef, Pork, Salt, fish, Butter, Cheese, Corn and Flower, as well as Beer’. In the 1680s, the Irish salt beef trade to the West Indies was worth about £45,000 a year, which was equal to 40 per cent of the value of all English exports to the sugar islands.56 Ligon advised that anyone intending to set up a sugar plantation on Barbados could double his investment by bringing out a cargo of English goods. There was a ready market, he assured would-be investors, for linen shirts and petticoats, Irish rugs for bedding, stockings and Northampton boots and shoes; there was also great demand for black ribbon due to the high rate of mortality on the islands.57 Dalby pressed his point home when he reminded his readers that all those ‘Industrious People Employ’d at home in manufacturing’ were increasingly reliant on the colonies.58 There was some truth in his claim. In the 1680s, about 20 per cent of all England’s exports of manufactured goods were absorbed by the extra-European market. Barbados alone consumed one third of all the exports London sent to the colonies.59

European trade was still the mainstay of the seventeenth-century English economy. Europe consumed almost all of England’s woollens and stuffs, Yarmouth herrings, lead and tin, and provided most of the flax, iron, timber, pitch and tar needed by the nation’s textile, metal and shipbuilding industries.60 But European trade was stagnant, its value increasing only incrementally each year. From the 1660s onwards, the dynamic sector of the economy was colonial trade, the value of which quadrupled in the last quarter of the century. While England sent the colonies growing quantities of goods and commodities, in return the amount of sugar and molasses, tobacco, coffee, rice, pepper and spices flowing into England increased each year, until by 1700, more than a third of England’s imports were tropical groceries.61 By this time about a third of England’s exports were now re-exports of these commodities. In the northern European ports, where the demand for English woollens and fish was low, colonial goods helped to balance England’s trade deficit.62

On the Continent, calicoes and tobacco were the most popular colonial goods, but in England the desire for sweetness was overwhelming. The English loved sugar even before they began producing it in their own colonies. A German traveller in Elizabethan England noticed that the teeth of aristocratic women (including the queen) were rotten, due to the fact that they constantly sucked on comfits, mixed sugar with their wine and even used it to glaze their roast meats.63 As production got off the ground in Barbados and more sugar than ever before began arriving in the port of London, its price halved and domestic consumption trebled as the circle of people who could afford it widened. By the 1690s, there were 40 confectioners in London, selling jams, bonbons and pastries to the well-heeled.64 An occasional sugary treat was now within the financial reach of a skilled craftsman, and the economist Gregory King noticed that the availability of sugar had increased the amount of fruit and vegetables eaten by the rural population. Now that it was affordable to make apples and pears, gooseberries and redcurrants palatable, they appeared frequently in pies and preserves on farm dining tables.65 By the late seventeenth century, sugar was no longer used as a spice but as a principal ingredient in an increasing number of recipes. In the space of a few decades, it had become a kitchen staple.

Unlike the Asian and Middle Eastern trades, dominated by wealthy merchants organised in companies, trade with the Americas was conducted by a medley of men from the middling sort. Shopkeepers, soap boilers, tailors and craftsmen invested in American ventures.66 These small-scale merchants formed a distinct City-based group, which supported Parliament in the early stages of the civil war, and once the Commonwealth was established in 1649, they gained a level of influence within the government disproportionate to their real social and economic weight. Cromwell embarked on a militant foreign policy promoting English interests against their erstwhile allies the Dutch (resulting in the first Anglo-Dutch War, of 1652–4), and authorised England’s first government-led expedition to conquer the colonial territory of a European rival: in December 1654, a fleet sailed for the Caribbean, where the following year it captured the island of Jamaica from the Spanish.67 In addition, the Cromwellian state sought to shut European competition out of the colonial trade and allow the English government to reap the rewards. The Navigation Act of 1651 stipulated that the produce of English colonies in the Americas could only be transported on English ships. In 1660, a further Act decreed that all colonial goods were to be channelled through England even if their eventual destination was Europe–and they could only be re-exported once the proper customs duties had been paid. Likewise, all slaves, food and manufactures sent to the Atlantic colonies were to be carried on English ships. In return, the 1661 Tariff Act placed prohibitive duties on foreign sugars entering England, thus giving West Indian planters a protected home market.68

In sugar the English found a commodity that compensated them for the lack of silver deposits in their colonies. At the end of the seventeenth century, England imported 320,000 hundredweight of West Indian sugar, worth about £630,000. The Crown earned 2s. 8d in customs duties on every hundredweight.69 But it was not just the intrinsic value of sugar that contributed to England’s prosperity. As valuable as the commodity itself was the bustle of commerce and industry that grew out of the sugar trade. The West Indies lay at the heart of the First British Empire, binding all the other colonies together in a web of exchange that stimulated the growth of maritime skills and knowledge, industry and financial services. The seventeenth-century economist Charles Davenant recognised that these were ‘more truly [the] riches of a nation than (gold and silver)’.70 The First British Empire fostered the growth of a new class of planters, merchants, financiers and industrialists whose wealth, based on the proceeds of trade rather than land, eventually gained them sufficient economic, social and political power to challenge the dominance of the landed aristocracy. The Atlantic trading system that developed out of England’s American empire underpinned the structural changes and economic development that eventually culminated in Britain’s Industrial Revolution.71