16

Hinterland Greek

Introduction

The rarity of knowledge of ancient Greek and its strange alphabet gave the language a mystique in the popular imagination. In low-class circles, more often than Latin, Greek was associated with extreme, other-worldly intellectual prowess and arcane, even sinister arts. In the course of this chapter, we will find Greek being cited, used or abused in a variety of recherché contexts ranging from accusations of witchcraft, caricatures of menacing Jesuits, the dialects of the criminal underclass, the display of prodigiously intellectual dogs and pigs, the lives of notoriously uncouth Scotsmen, Welsh dream divination and downmarket pharmaceuticals and sex manuals. But the story, which will return at its conclusion to the Bible, begins with Greek’s special status within Christianity.

Popish, Satanic and criminal Greek

When in the 16th century Jerome’s Latin Vulgate, long the officially recognized Bible of the Catholic Church, began to be seriously rivalled by vernacular versions in English (et al.), the Greek New Testament attracted sustained attention. For the first complete English edition of the New Testament (1526), William Tyndale had used the Greek text as well as the Latin Vulgate. Erasmus’ Greek New Testament, published a decade earlier in 1516, had proved seminal in the emergence of Renaissance Christian Humanism and the expertise in Greek for which educated Protestants like Tanneguy Le Fèvre, head of the Protestant Academy in Saumur, France, and his daughter Anne,1 were later to become renowned; Martin Luther himself found numerous errors in the Vulgate Latin by comparing it in detail with the Greek.2 It is now held that, as an Aramaic speaker, Jesus merely knew enough Greek (the international language of the eastern Roman Empire) to communicate with Roman officials in it. But in the Renaissance and Early Modern period, it was widely believed that Jesus had spoken Greek as his first language. God himself, through Christ, was thus held to have communicated with the multitudes of the 1st century ce in Greek.3

On the other hand, especially after the Gunpowder Plot, knowledge of Greek was often perceived as suggesting ominous Jesuit connections. In the next chapter we shall see that, when in the early 18th century a Frenchman disguised as a native of Taiwan (then called Formosa, ‘beautiful’ in Latin) wanted to explain to Britons why he knew ancient Greek, he claimed that he had been taught it by a Jesuit missionary to the island.4 Study of classical Greek authors as well as the New Testament was by that time being exported across the planet by the Society of Jesus. The best minds at the Jesuit school in Rome had in 1599 enshrined several Greek authors in their official plan for education, the Ratio atque Institutio Studiorum.5 The men involved in the plot to blow up the House of Lords on 5th November 1605 included several from families who had protected Jesuit priests during the reign of Elizabeth I. Despite the attempts of Father Henry Garnet, the English Jesuit Superior, to dissuade Robert Catesby, the leader of the conspiracy, from committing any act of violence, the government was determined to incriminate the Jesuits. Garnet himself was executed. The Jesuits, with their expertise in Greek, were subsequently often blamed for any national disasters, including the 1666 Great Fire of London, the Popish Plot of 1678, and even the sinking of the Titanic in 1912.6

The mystical potency of Greek was certainly sometimes associated by Anglicans with ‘papists’. William Perrye was an idle 13-year-old in Bilston colliery town who feigned Satanic possession in order to avoid school:

The trigger for his fit was the Greek of the first verse of the Gospel of St. John, ‘In the beginning was the word, and the word was with God, and the word was God’.8 William claimed to have been bewitched by a poor old woman named Joan Cox. She was put on trial for witchcraft, and narrowly escaped conviction. The Bishop of Lichfield was summoned and unmasked the boy’s imposture. The learned divine recited the twelfth verse of St. John, ‘which the boy supposing the first, fell straightway into one of his agonies’.9 But when the famous first verse, en archēi ēn ho logos, was read in Greek, Bilston Bill did not recognise it as his customary cue. In due course, he apologised.10

All Roman Catholics, regardless of what seems here to be connections between Greek and their practice of exorcism, were conversant with Latin. Latin’s associations with popish rituals and superstition were only underscored by the Latin element in canting, the supposedly secret language of highwaymen. This was publicly exposed as early as 1610 by a writer under the pseudonym ‘Martin Mark-all, Beadle of Bridewell’. At the end of his Apologie, he explains the origins of the patois used by the criminal underclass of his day, a mixture of Latin, English and Dutch. Bridewell Prison had been established in 1553 to control London’s ‘disorderly poor’. In a fascinating section offering a history of robber gangs of England, its Beadle, or governor, describes the day when, he claims, the lingua franca of highwaymen was invented.11

Tensions had grown between the two biggest robber gangs in the early 16th century. The dominant gang for several years was led by a tinker named Cock Lorrell, ‘the most notorious knave that ever lived’. But a new ‘regiment of thieves’ sprang up in Derbyshire, led by one Giles Hather. This 100-strong gang called themselves ‘the Egyptians’. Hather’s woman, a whore named Kit Calot, was ‘the Egyptians’ Queen’. The Egyptians disguised themselves by donning black make-up. They made good money from fraudulent fortune-telling. The two ‘Generals’, Lorrell and Hather, decided to cooperate rather than compete with one another. They met as if they were establishing a new republic, ‘to parle and intreat of matters that might tend to the establishing of this their new found government’.12 This momentous diplomatic event took place in a famous cave in Derbyshire’s Peak District, then known as ‘The Devil’s Arse-Peak’ (prudish Victorians renamed it ‘Peak Cavern’). The most important measure was

The speakers of the canting tongue, most of whom will have been illiterate, did not write it down. The Dutch element will have come from the intensive contact between the English and Dutch sailors, especially those who had escaped from the ships into which they had been pressganged in the port cities of northern Europe.14 The priority of Latin was inevitable: it will have been the only language of which most members of the gangs (at least, everyone who had been to Catholic churches or through the courts of law) will have acquired at least a smattering. The lost Latinate language of the thieves and highwaymen of England was probably not ‘devised’ overnight in that cave in Derbyshire. But the fact that the ‘Beadle of Bridewell’ describes it in such detail suggests that he knew whereof he spoke.

Yet, by the time Classics emerged as a discipline at the dawn of the 18th century, it was not Latinate canting, but another underworld dialect, known as ‘St. Giles’s Greek’, which was favoured by metropolitan Georgian felons. The enterprising Francis Grose (who may have penned the burlesque of the Iliad discussed above p. 3–4) treated it to a lexicographical investigation in his Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1785; much reprinted). (Figure 16.1) Grose was responding, no doubt, to the vogue for comprehensive dictionaries (Samuel Johnson’s 1755 A Dictionary of the English Language is the most famous, but it had followed hard on the heels of Lancashire-born schoolmaster Robert Ainsworth’s Thesaurus Linguae Latinae Compendarius (1736) and Benjamin Martin’s Lingua Britannica Reformata [1749]). Grose’s subversive title parodied such scholarly works as Laurence Echard’s Classical Geographical Dictionary (1715), Andrew Millar’s An Historical, Genealogical, and Classical Dictionary (1743) and John Kersey’s New Classical English Dictionary (1757). He expressed scorn for pedantic classicists ‘who do not know a right angle from an acute one, or the polar circle from the tropics, and understand no other history but that of the intrigues between the eight parts of speech’ while looking ‘down with contempt’ on everyone else.15 Yet his biographer believes that he received a classical education in his boyhood; there is substantial knowledge of ancient authors on display in his A Treatise on Ancient Armour and Weapons (1786).16 After an army career, Grose worked as an antiquarian and draughtsman; a warm-hearted man of ready wit, after visiting Scotland he became one of Robert Burns’ closest friends.17

Grose explains in his preface that ‘the Vulgar Tongue’ consists of ‘the Cant Language, called sometimes Pedlars’ French, or St. Giles’s Greek’, plus burlesque or slang terms ‘which, from long uninterrupted usage, are made classical by prescription’. He satirically explains what he means by ‘the most classical authorities’ for the latter category: ‘soldiers on the long march; seamen at the capstern; ladies disposing of their fish, and the colloquies of a Gravesend boat’.18 Grose had served at non-officer ranks amongst the rank and file of the army, having joined a foot regiment in Flanders as a volunteer at the age of 17. When serving in the Surrey Militia, he had met many robbers and highwaymen because he was charged with a clampdown on their activities. He took their lower-class speech seriously and created a scholarly lexicographical resource. He found some material in previous collections of slang, but also conducted primary research on nocturnal strolls amongst the London underworld with his servant Tom Cocking.19

Criminal cant was called ‘St. Giles’s Greek’ because the parish of St. Giles (between Newgate Prison and the Tyburn gallows, now part of Camden) was notoriously the operating ground of thieves and pickpockets. ‘Greek’, being known by nobody except the elite, was a convenient term for the ‘cant’, a gibberish few understood.20 These entries from the dictionary show that ‘St. Giles’s Greek’ adopted a humorous approach to classical culture, Latin and learned etymologies: cobblers were called ‘Crispins’ after two early Christian saints. Blind men were called ‘Cupids’ and prostitutes ‘Drury Lane Vestals’. Ars Musica meant ‘a bum fiddle’, a person always scratching their posterior (arse + a musical instrument); Athanasian wench means a promiscuous woman, who will sleep with anyone who offers, because the first words of the Athanasian creed are ‘quicunque vult’, whosoever wants … ; Circumbendibus means a story told with many digressions; the entry under Fart includes an obscene rhyming couplet in Latin; Hicksius-doxius means ‘drunk’, by making comical pseudo-Latin out of sounds suggestive of hiccups; Myrmidons means ‘the constable’s assistants’ by association with Achilles’ stalwart men-at-arms in the Iliad; Trickum legis—a hybrid Anglo-Latin comical phrase meaning ‘legal quibble’; and Squirrel means a prostitute because it hides its backside with its tail. Here Grose cites a French authority who quoted a Latin proverb meretrix corpore corpus alit, ‘a whore nourishes her body with her body’.21

Greeklessness, race, gender and class

In a collection of essays, Grose remarks that ‘Greek is almost as rare among military people as money’.22 The same could be said in the 18th century of many more middle- and upper-class men than would have cared to admit it. The result was that Greek acquired a totem-like status, and often appeared in rhetorical situations where exclusion from not only polite society but even fundamental rights as a human being were at stake; for example, when white people wanted to distinguish their intellectual abilities from those of black ones. An African American named Alexander Crummell travelled to Cambridge University and learned Greek during his theological studies at Queen’s College (1851–1853), financed by Abolitionists. He later said that he had partly been motivated by a conversation he heard as a free but impoverished errand boy in Washington DC in 1833 or 1834, when pro-slavery thinkers were on the defensive. The Senator for South Carolina, John C. Calhoun, declared at a dinner party that only when he could ‘find a Negro who knew the Greek syntax’ could he be brought to ‘believe that the Negro was a human being and should be treated as a man’.23

The author of a Cornwall/Devon newspaper article, written in 1852, sneers at what he sees as do-gooders with cranky views on education, the sort of ‘educated man who believes that an ignorant servant, who cannot with both her eyes read “slut” visibly written on a dusty table, can … read a Greek chorus with her elbows’.24 The rhetorical effect here comes from the manifest absurdity of imagining that a working-class female could achieve the educational standard symbolised by reading Greek lyric verse. The point depends on extreme class snobbery as well as misogyny: the serving girl’s brain can never be developed (the body part mentioned is her elbows, symbol of manual labour). She is only by a syntactical hairsbreadth not dismissed as sexually depraved as well as educationally retarded.25

Of all forms of Greek, the words of the Greek tragic chorus seemed the most potent symbol of the elitist class connotations of the classical curriculum. For Victorians, the chorus symbolised esoteric intellectual matters, as people today talk about ‘rocket science’ or ‘brain surgery’. In the polemics of educational reformers, such as those who established the College of Physical Science at Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1871, the metres of the Greek chorus become the emblem of ‘useless’ education for its own sake. In 1871 a Yorkshire advocate of reformed, utilitarian and science-based education wrote an article in The Huddersfield Chronicle and West Yorkshire Advertiser entitled ‘Useful versus Ornamental Learning’: he said,

The new College grew out of the North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers, a response to the horrendous mining catastrophes in the earlier 19th century. The first session, in 1871–1872, entailed 8 teaching staff, 173 students and the 4 subjects of Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry and Geology. But the antithesis between practical science which could save miners’ lives and ‘useless’ classical scholarship was curiously subverted in the figure of John Herman Merivale, the College’s first student, who became its first Professor of Mining. He was warmly supported in his desire to alleviate mining conditions by his father, the Very Reverend Charles Merivale, Dean of Ely Cathedral, classical scholar, translator of Homer into English and author of A History of the Romans under the Empire (1850–1862). Merivale Senior also translated Keats’ Hyperion into Latin verse (1863).

The Greek of freakish animals

The freakishness which labouring-class people associated with Greek comes over in a poem called ‘The Fool’s Song’ by Thomas Holcroft, the revolutionary son of an itinerant pedlar. Holcroft was charged with treason in 1794. He considers all kinds of improbable situations with as much likelihood of coming about as a fair system of justice in Britain:

These are imagined prodigious fauna, but the provincial Englander’s concept of the distance between real life and the ancient Greek language could be weirdly proven by performing animals. The British showed their intellectual superiority over the French in 1751 during a war between educated hounds.

When Le Chien Savant (or Learned French Dog, a small poodle-ish she-dog who could spell words in French and English) arrived in London, she was trumped by the New Chien Savant, or learned English Dog, a Border Collie.28 The triumphant English Dog toured Staffordshire, Shrewsbury, Northamptonshire, Hereford, Monmouth and Gloucester, as well as the taverns of London. She could spell PYTHAGORAS and was advertised as a latter-day reincarnation of the Samian philosopher/mathematician himself.29 Exhibited in a public house in Northampton in November 1753, this Learned Dog (for there were several other rival hounds touring the country during the 18th and earlier 19th centuries) had a range of talents. The local newspaper, the Mercury, recommended a visit to the exhibition heartily:

This hound could tell the time, distinguish between colours and, at the climax of the show, display powers of Extra-Sensory Perception by reading spectators’ thoughts.31

The erudite hound tradition may have been inspired by Scipio and Berganza, the canine conversationalists in Miguel de Cervantes’ social satire El Coloquio de los Perros (Conversation of the Dogs), who understand the role played by displays of Latin and Greek in the Spanish class system. The last of Cervantes’ Exemplary Novels (Novelas ejemplares, 1613), of which English translations were fashionable reading, the dialogue is overheard by a man in hospital with venereal disease. Scipio and Berganza are the hospital guard dogs. They agree that there are two ways of abusing Latin quotations. Berganza, who learned Latin tags when owned by schoolmasters, resents writers who insert ‘little Scraps of Latin, making those believe, who do not understand it, that they are great Latinists, when they scarcely know how to decline a noun or conjugate a verb’.32 Scipio, the more educated and cynical hound, sees humans who do know Latin as more harmful. Their conversations even with lower-class cobblers and tailors are flooded with Latin phrases, incomprehensible to their listeners and therefore creating opportunity for exploitation of the less educated.

Scipio woofs references to the myths of Ulysses and Sisyphus. He would rather bark about philosophy than abuses of Latin. Like Plato’s Socrates, he becomes exasperated when his interlocutor relates anecdotes rather than producing definitions. Here is the dialogue after Berganza concedes that he does not know the Greek etymology of the word ‘philosophy’ and demands to know from whom Scipio learned Greek: Scipio responds, mysteriously,

Scipio is in danger of exhibiting the very intellectual snobbery which he purports to criticise. But it is Berganza who concludes the discussion of Classics with a striking, problematic image. He compares people who deceive others into thinking they are refined by faking knowledge of Latin and Greek with people who use tinsel to cover up the holes in their breeches. But he also suggests that such intellectual imposters be exposed by the torture methods used by Portuguese slavers on ‘the Negroes in Guinea’, thus revealing that he is not himself free from ‘human’ indifference towards the plight of slaves.34

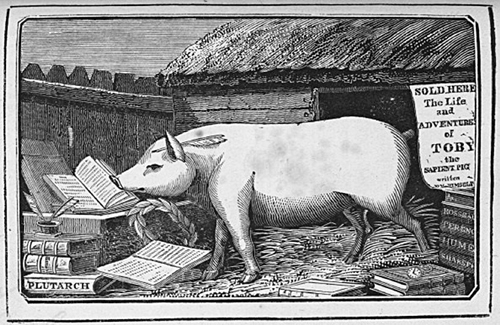

Most poignant of all, given Burke’s insulting claim that putting scholarship anywhere near working-class people was to cast pearls before swine, were the Sapient Pigs which toured pubs in late Georgian England exhibiting their prodigious intellect. The most famous billed himself as Toby, the SAPIENT PIG, OR PHILOSOPHER OF THE SWINISH RACE. There was more than one such pig; Richard Porson, who was acutely aware that he had risen from a working-class background to become the most celebrated Greek scholar in the land (see pp. 294–9), wrote a Greek epigram for one in 1785 (prior to Burke’s notorious diatribe), appending a humorous short article about him. It opens by calling the pig a ‘gentleman’, and hoping that said ‘gentleman professing himself to be extremely learned, [he] will have no objection to find his merits set forth in a Greek quotation’. Porson then supplies the Greek, and an English translation which he claims he has procured from the Chien Savant, because ‘it is possible that the pig’s Greek may want rubbing up, owing to his having kept so much company with ladies’.35

The frontispiece to the autobiography The Life and Adventures of Toby the Sapient Pig implies that the learned swine’s preferred reading was Plutarch (Figure 16.2). The poet Thomas Hood saw that no amount of learning could ultimately save a pig—or a lower-class human—from being sacrificed in the interests of the voracious ruling class. His ‘Lament of Toby, the Learned Pig’, woefully concludes with the poor porcine, despite being crammed with Classics at Brasenose College, Oxford, being fed and readied for slaughter:

Knowledge of ancient Greek authors was absolute proof of the prodigious intelligence of an animal. This is, in turn, telling evidence of the degree of difficulty—and therefore cultural prestige in financial and class terms—associated by the provincial inn-going public with such an arcane educational curriculum.

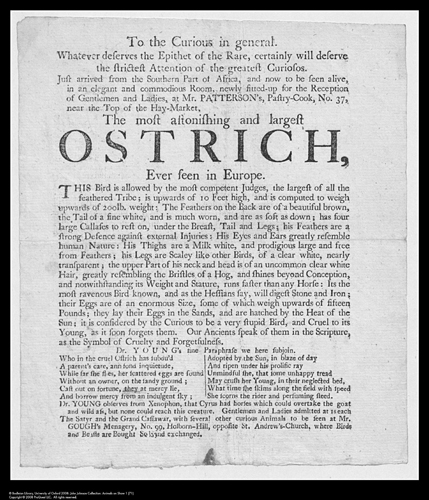

Ancient Greek authors sometimes pop up in other strange forms of plebeian entertainment involving fauna, especially in London. When Georgian showmen invited the public to view their exotic ostriches, they were sure to mention Xenophon.37 ‘The most astonishing and largest OSTRICH ever seen in Europe’ was advertised as on display at the Pastry-Cook Mr Patterson’s, no. 37 Haymarket. The advertisement informs the reader that ‘Dr. YOUNG observes from Xenophon, that Cyrus had horses which overtake the goat and wild ass, but none could reach this creature’38 (Figure 16.3). The reader is also told that a Satyr can currently be viewed, along with the rare Cassowary bird from New Guinea, at ‘Gough’s Menagerie’, no. 99, Holborn Hill. Appearances in London were even made by the terrifying snake-like monster called the basiliskos mentioned in ancient texts including Heliodorus’ Ethiopian Tale (III.8), Artemidorus’ Interpretation of Dreams (IV.56—see further below p. 337) and Pliny’s Natural History (VIII.78). There had been a 17th-century craze for the alleged discoveries of baby basilisks lurking in eggs, and examples, when dried, could reach a good price across western Europe. A handbill in the British Library entitled ‘A Brief Description of the Basilisk, or Cockatrice’ shows that at least one fake basilisk was to be viewed in London. The handbill informs us that its owner, an impoverished Spaniard named James Salgado, had presented it to some gentlemen in London when begging for financial assistance.39

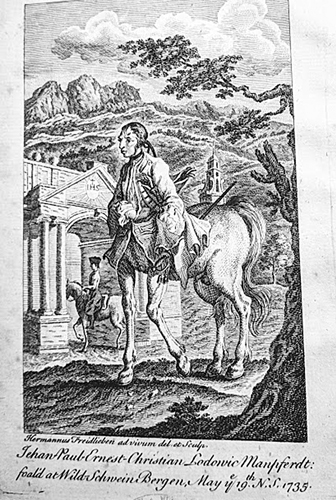

In April 1751 the London Magazine published an article supposedly exposing an April Fools’ Day scam.40 The story illustrates the kind of freak show, with an ancient Greek flavour, which snobbish readers thought credulous people of the lower classes could be tempted to pay to view. A few weeks earlier, a pamphlet had appeared announcing that ‘the surprising CENTAUR, the greatest Wonder produced by Nature these 3000 Years’ was to be exhibited on April 1st at the Golden Cross, Charing Cross41 (Figure 16.4). The pamphlet described how the Centaur, whose name was Paul Ernest-Christian-Ludovic Manpferdt (‘Manhorse’), had been born near a Jesuit College in Switzerland and had been transported with difficulty to England. The Centaur has failings, said the pamphlet, especially dunging and urinating in any company, ‘a propensity to all kinds of Indecency and Lewdness in his Talk’, and drinking an ‘immense quantity of Claret’.42 The price of seeing the Centaur was to be five shillings for nobility and gentry and one shilling to everyone else. These extortionate sums are part of the joke; a shilling was more than most working people at the time could earn in a whole day.

Uncouth Caledonian Hellenists

Further north, in Scotland, where at least until the late 19th century the education system was kinder to low-class children (especially boys) than it was in England (see further Chapter 11), there was a curious phenomenon of notable Hellenists from lowly origins who retained a preference for a lifestyle too coarse to allow them to qualify as gentlemen. William Wilkie, the ‘Scottish Homer’ fluent in ancient Greek, composed a nine-book epic about Thebes while personally ploughing his few fields in order to plant potatoes. The son of a farmer who had fallen on hard times, Wilkie’s aptitude for classical languages was spotted at Dalmeny Parish School. While he was at Edinburgh University he baffled leaders of the Scottish Enlightenment, Adam Smith and David Hume, and a friend named Henry Mackenzie recalled him as ‘superior in genius to any man of his time, but rough and unpolished in his manners, and still less accommodating to the decorum of society in the ordinary habits of his life’.43

Wilkie was forced to leave university when his father died, leaving him with nothing but an unexpired lease of a farm in Midlothian, some livestock, and three dependent sisters. He was an outstanding agriculturalist who made advances in the cultivation of the potato. A biographer recalls that while he worked at his crops

The epic, in rhyming couplets, is heavily influenced by Pope, steeped in first-hand knowledge of Homeric Greek and virtually unreadable. But in his eccentric Preface, Wilkie takes pains to stress that readers of any class can enjoy poetry set in ancient times:

Although he became less indigent, being appointed to a Chair in Natural Philosophy at St. Andrews, Wilkie was inveterately mean with money. He said, to the end of his days, ‘I have shaken hands with poverty up to the very elbow, and I wish never to see her face again’. He identified physically with the labouring class. His biographer reports that he slept in large piles of dirty blankets, and had an

He cannot have smelled pleasant, either: ‘He used tobacco to an immoderate excess, and was extremely slovenly in his dress’. Little wonder that Charles Townsend said that he had ‘never met with a man who approached so near to the two extremes of a god and a brute as Dr Wilkie’.46

While Wilkie was composing his epic, the Professor of Greek at Glasgow, James Moor, was also horrifying polite society by his appalling manners. Born in Glasgow, Moor was the son of a Mathematics teacher. He matriculated in 1725, became a protégé of the Professor of Moral Philosophy, Francis Hutcheson, and graduated MA in 1732. He taught as a school teacher and a private tutor to the children of Scottish aristocrats, before becoming the University’s librarian in 1742. He was appointed to the Chair of Greek four years later. An accomplished scholar, he collaborated with the University’s printers, the Foulis brothers (themselves risen by hard work from a working-class childhood as the sons of a maltman) on their celebrated editions of Latin and especially Greek Classics.47 But he was boorish in the extreme, living with his working-class wife in quarters regarded as unsavoury by colleagues. He spent much of his time in taverns and, when drunk, would engage in unseemly brawls; his Faculty had to discipline him for attacking a student with a candlestick. Moor died as he had often lived, insolvent.48

Arcane Greek lore

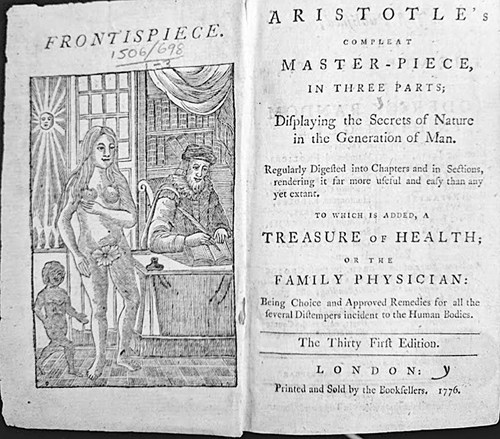

Earlier, we saw that pouring forth quotations in Greek might be construed as a sign of possession by a poor old woman believed to be a witch. The supernatural associations of Greek were combined with its aura of high erudition in the strange phenomenon whereby compounds of ancient Greek stems were used in the advertising of medicinal and cosmetic lotions and potions, simultaneously to associate them with precious wisdom and with an almost supernatural potency. ‘We must walk through Holborn and the Strand with a Greek dictionary in hand’, declares a journalist in 1851.49 This marketing technique is parodied in the black-tinted hair oil with the brand name Cyanochaitanthropopion (Blue-Black-Hair-for-Humans) sold in Samuel Warren’s 1841 novel about the adventures of an impoverished draper’s assistant, Ten Thousand A-Year.50 A similar sense of the special powers of Greek knowledge is attested by the popularity of the ancient Greek handbook of dream divination, Artemidorus’ Oneirocritica, which was available in numerous Greek and Latin editions; it was translated into German in 1540, French in 1546, Italian in 1547, English by 160651 and even Welsh in 1698.52 But the book which most clearly associated ancient Greek wisdom with arcane lore was the bestseller Aristotle’s Masterpiece or Compleat Masterpiece, sometimes entitled The Works of Aristotle, the Famous Philosopher. Although not by Aristotle, this anonymous racy manual on sex, reproduction and midwifery, with lavish and exciting illustrations, was first published in 1684 and reproduced in hundreds of variant editions thereafter, both English and Welsh.53

A copy was bought in 1700 by John Cannon, an agricultural labourer, for a shilling. He wanted to ‘pry into the Secrets of Nature especially of the female sex’. In order to verify ‘Aristotle’s’ accounts, he bored holes in the wall of the family privy to spy on the maid.54 Cannon did not find it in a catalogue put out by mainstream publishing houses. It was, writes Mary Fissell, ‘part of a low culture of ephemeral productions, and sold in a variety of venues including “rubber goods shops”, which also sold contraceptives, abortifacient pills, etc.’ Her brilliant essay describes how this ‘wildly popular sex manual … taught and titillated through the early modern period and beyond’ across the entire class spectrum.55

The reasons why the anonymous author invoked the authority of Aristotle are several. As the acknowledged expert in most scholarly fields—Dante’s ‘Master of Those who Know’—Aristotle possessed the cachet of the intellectual heavyweight.56 But he was also seen as a sex guru. This perception was connected with a prurient 13th-century fiction which described Aristotle’s affair with the courtesan Phyllis, who agreed to have sex with him if she could ride on his back as a dominatrix. The silly tale was made available in English by 1386, when John Gower told it in his collection of sex stories Confessio Amantis. But the immediate impulse to publish under Aristotle’s name was the warm response which an authentic ancient Greek text attributed to him had received. An English translation of The Problemes of Aristotle, with other Philosophers and Phisitions. Wherein are contained diuers questions, with their answers, touching the estate of mans bodie had been published in 1595.

This book is easy to read; it was written by disciples of Aristotle, probably with the intention of publicising Peripatetic biology amongst a general ancient readership. The questions will have been normal in ancient Greek society, but may well have shocked Early Modern Christians. Why do some men wink after copulation? Why do some eunuchs desire women and excel at ‘the act of Venerie’? Why do women love the men who deflower them? Why do fat men produce scanty semen?57 Aristotle’s name soon became a byword for knowledgeability—and knowingness—about sex.

Purchasers of Aristotle’s Masterpiece, believing it to be, like the Peripatetic Problems, a translation of an authentic ancient Greek work, were tempted to part with their money by an almost invariable picture of a naked woman, often being inspected by a scholarly gentleman who might be assumed to be Aristotle, reproduced opposite the title page (Figure 16.5). One popular edition included bawdy poems designed to be read out to a woman being seduced and promising mutual gratification, which it explains (inaccurately) is required for conception.58 But it also contains sensible information about care of the pregnant woman, the development of the unborn child, labour and parturition. This was one reason why it was so much consulted by women as well as men (Molly Bloom in James Joyce’s Ulysses has her own copy59), but another is that, like John Cannon, adolescent girls were desperate to find out what to expect when they had sex with men. Mary Bertenshaw was 14 and working in a Manchester factory when her friend Gladys brought in Aristotle’s Masterpiece. Mary describes it as ‘a secret book’. They read it, laughing during their breaks until their boss discovered what they were doing. But Mary was grateful that she had read the book when her mother became pregnant.60

Finally, the ancient Greek savant’s spurious manual lay behind one radical’s questioning of Christian dogma, bringing this chapter full circle back to the issue of the Bible. Francis Place went on to play a leading role in the 1824 Repeal of the Combination Act, thus helping early Trade Unionism, and later in Moral-Force Chartism. But he was originally the illegitimate son of a man who ran a Drury Lane sponging-house, born in 1771. Before he was apprenticed to a maker of leather breeches in Temple Bar at the age of 14, Francis used to tour the bookstalls of London looking for exciting anatomical pictures in medical works, and read the Masterpiece while still at school. Aristotle, who did not believe in the direct involvement of any deity in human life, would have approved of one upshot of the Masterpiece’s physiology. Greek, however inauthentic, here did work that many of Place’s contemporaries would have regarded as diabolical. For Place said that it was learning from its scientific description of the process of human conception that made him doubt forever the whole Biblical tradition of the Virgin Birth.61