2

The invention of Classics and the emergence of class

What does ‘Classics’ mean?

Pagan Latin and (to a far lesser extent) Greek authors were read by English-speaking elites long before. But British Classics, under that title and as we know it today, was born as a discipline during the period between the Glorious Revolution and the mid-18th century. This was against the background of the Bill of Rights, the circumscription of the powers of the monarchy, the Whig and Anglican ascendancy and, in 1707, the Act of Union. This chapter traces the emergence of the label and of the closely related term class to designate a social, economic and political status. It enquires into the reasons why they emerged when they did, and explores some challenges made to the claim of the wealthier ‘gentlemen’ class, on account of the difficulty of the ancient languages and the costly leisure required to acquire them, to exclusive ownership of classical authors.1

Thomas Brown (Figure 2.1), a brilliant satirist, translator and a major influence on Swift, Addison and Steele, was also known to be a linguistic innovator.2 His Letters from the Dead to the Living, which are informed by Lucian of Samosata’s satirical Dialogues of the Dead, include one written by a fictional physician. ‘Giuseppe Hanesio, High-German Doctor and Astrologer’ records from the Underworld the many cures he had effected when he was alive. His patients had included Pope Innocent XI and the Sophy of Persia. He had also cured the Mughal emperor ‘Aurung-Zebe’ of epilepsia fanatica: ‘by my Cephalick Snuff and Tincture, I made him as clear headed a Rake as ever got drunk with Classics at the University, or expounded Horace in Will’s Coffee-House’.3 The joke here is that the notorious religious intolerance of the fanatical Aurung-Zebe (Muhi-ud-Din Muhammad) had been deactivated by making him the opposite of clear-headed. He had been made as confused as rakish students reading classical authors at the university, ‘Classics’ here apparently meaning, rather than ancient authors or texts, his fellow students and perhaps tutors of Greek and Latin themselves.

Brown had an axe to grind against university teachers of ancient languages. He was born into a relatively poor Shropshire household. His father, a farmer, died when he was eight. He was only educated because his county offered free schooling at that time. By scholarships he proceeded to Christ Church, only to develop an aversion to the then-Dean, Dr. John Fell, a disciplinarian. The story goes that Brown, who loved to drink, was about to be expelled, but Fell challenged him to translate Martial I.32. A literal translation of this poem would run, ‘I do not love you, Sabidius, and I am unable to tell you why. All I can say is this: I do not love you’.4 Brown is said to have responded,

Brown, to whom the discussion will return later in this chapter, left Oxford without a degree. He eked out an income to support his libertine lifestyle, first as a schoolmaster in Kingston-upon-Thames and then as a Grub Street writer and translator. His own experience of rakishly getting drunk on or with ‘Classics’ at university surely lies behind that early instance of the term.

Less than 70 years previously, ‘classics’ could still mean ‘war trumpets’ or ‘trumpets-calls’, as the neuter noun classicum, plural classica, did in canonical ancient authors.6 In 1635 King Charles I commissioned an epic poem on his predecessor Edward III’s achievements from Thomas May, renowned translator of Lucan’s Civil War. In one passage May draws a comparison with the impact made by Julius Caesar’s army in France long ago,

By ‘dreadfull Classicks’ being heard in parts, May does not mean that Caesar subjected the Gauls to long recitations of ancient Greek and Latin literary works.

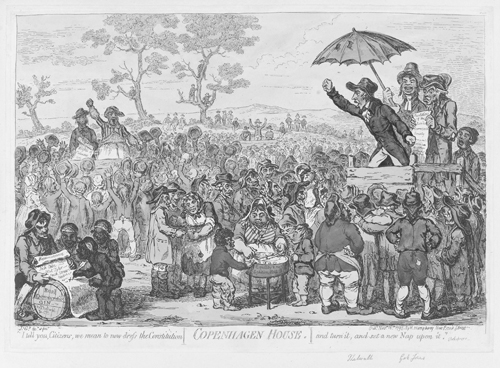

What have military trumpets to do with either class or Classics? When the Romans heard their Latin noun classis, from which was derived that word for trumpet, classicum, it contained a resonance that we do not hear when we say either Classics or class: deriving from the same root as the verb clamare (‘call out’), a classis consisted of a group of people ‘called out’ or ‘summoned’ together by trumpets. It could be the men in a meeting, or in an army or the ships in a fleet. The word has always been associated with Servius Tullius, the sixth of the legendary kings of early Rome, who was thought to have held the first census in order to find out, for the purposes of military planning, what assets his people possessed (Livy I.42–.4). This explains the ancient association of the term class with an audible call to arms. Yet, by not long into the 18th century, the term was adopted in order to distinguish different strata within English society: in 1796 the radical democrat John Thelwall refers to the treatment of the different ‘classes’ by Servius Tullius when trying to arouse the British working class to imitate the French revolutionaries.8 (Figure 2.2) The working poor of England began to be called members of ‘the lower classes’ rather than just ‘the poor’ or members of ‘the lower orders’. The word ‘poor’ was too imprecise; the notion of hierarchical ‘orders’ too inflexible and too infused with medieval and feudal notions of birth-rank to accommodate the unprecedented new levels of social mobility.

The language of ‘rank’ lingered in John Locke’s Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693), written at the precise moment when ‘Classics’ was being invented as a subject label: ‘that most to be taken Care of is the Gentleman’s Calling. For if those of that rank are once set right, they will quickly bring the rest into order’.9 A new definition of the ‘Gentleman’ can be seen at work here (see below, pp. 29–33), but alongside the old term ‘rank’, the term class, which (like its ancient prototype) implied a status with an economic basis rather than an inherited rank, was a result of the incipient erosion, during the early industrial revolution, of the transparent and relatively stable hierarchical ranking system which had earlier governed the English social structure.10 The French and German languages soon imitated the English one, often replacing the terms état and Stand with classe and Klasse. Nevertheless, for most of the 18th century the labouring and artisanal classes were often spoken of as a mass of ‘commoners’ or ‘common people’. The term ‘working classes’, in the plural as a category including workers in industry, agriculture, craft, itinerant trade and domestic service, as well as unemployed people who could only hope to find work in those spheres, first appears at the time of the French Revolution.11 By 1815 the now-familiar double-barrelled terms ‘middle classes’ and ‘working classes’ had become accepted parlance.12 The more modern socio-economic usage emerged when writers such as Robert Owen began to employ the formulation ‘working class/es’ within widely read essays and journals in the second decade of the 19th century.13 The plural the Classics, meanwhile, had been used in English by 1679, as we shall see, to designate the corpus of Greek and Latin literature.

It is to the legendary first census that there must also be traced the origins of the term Classics. In Servius’ scheme, the men in the top of his six classes—the men with the most money and property—were called the classici. The ‘Top Men’ were ‘Classics’. This is why the late 2nd-century ce Roman miscellanist Aulus Gellius, could, by metaphorical extension, call the Top Authors ‘Classic Authors’, scriptores classici. This was to distinguish them from inferior or metaphorically ‘proletarian’ authors, scriptores proletarii (Noctes Attici XIX.8.15). Gellius recalls Cornelius Fronto exhorting him and another author that, when they were in doubt whether a noun should be singular or plural, to do as follows:

The metaphors are even more specific than that: classicus adsiduusque, here translated ‘of class and substance’, could equally well be translated ‘of the taxpaying class’, one specific meaning of the term adsiduus.

Every tradition of writing, art, music and sport—English Literature, Dutch painting, Jazz, motorcycles, horse races—now claims its own ‘Classics’, and in the case of English Literature, this custom began in the early 18th century not long after it was applied to texts in ancient Greek and Latin.14 But the most venerated Classics amongst all others have always been the authors of Greece and Rome—the supposed primi inter pares or ‘first amongst equals’ when compared with all the cultural Classici produced in world history. In its earliest instances, there is an additional definite article the prefixed to the term Classics, enacting a final sub-division by which the most elite texts of all can be identified by the few refined individuals supposedly able to appreciate them. The unit at Harvard University which studies these Greek and Roman ‘Hyper-Classics’ still styles itself ‘The Department of the Classics’.

The involvement, historically, of the study of Greece and Rome in the maintenance of socio-economic hierarchies is thus obvious in the very title Classics. Over the last three decades some scholars have considered abandoning it altogether, and replacing it with a label such as ‘Study of the ancient Mediterranean’ or ‘Study of Greek and Roman antiquity’ or even, in jest, ‘Ancientry’.15 Their motive has been to expand the study of the ancient communities where Greek and Latin were spoken to include all the other languages and peoples who shared this world, from Sumerians, Nubians, Phoenicians and Carthaginians to Gauls, Batavians and Etruscans. But surely the class connotation of the nomenclature Classics is ideologically just as objectionable as the ethnic one that privileges Greek and Latin over other ancient tongues.

The Attic Nights was a favourite Renaissance and Early Modern text, first printed in 1469.16 By 1602, the adjective classic, variously spelt classick, classicke and classique, is found occasionally, if only in scholarly contexts, to describe a canonical author or text of any era: William Perkins writes in a theological work written in 1602, ‘Neither Plinie (who writ after Paul) nor any other ancient classique author, doth make mention of Phrigia’.17 He needs to distinguish between ‘ancient’ classic authors and more recent ones, and seems to include St. Paul’s epistles amongst ‘classical’ works. Amongst scholarly writers, we find the term classic qualifying ‘folio’ in 1628,18 and a ‘word’ in the Latin language in 1646.19 By 1645, with the circulation in European circles of the Greek treatise On the Sublime attributed to Longinus (the first English translation, by John Hall, was published in 1652), Sir Dudley North fuses the idea of a top literary class derived from Aulus Gellius with the new interest in sublimity: ‘Farre more sublime and better Authours have discovered as little order, and as much repetition; witnesse the Collections of Marcus Aurelius, St. Augustines Confessions, and some of a higher Classe’.20 By 1694, the former Archbishop of Canterbury Willian Sancroft can be praised posthumously by another divine for having been ‘an admirable Critic in all the Antient and Classic Knowledge, both among the Greeks and Romans’, although here, too, the words ‘Antient and Classic’ probably include biblical literature.21

The inclusion of biblical literature and patristic writers in the category of ‘classic’ authors persisted in some quarters for decades. Anthony Blackwall, the author of an influential 1718 An Introduction to the Classics; Containing a Short Discourse on their Excellencies and Directions how to Study them to Advantage, felt impelled to correct any impression that he was disrespecting Christian texts with a long essay on the subject seven years later in 1725. Its title is The Sacred Classics Defended and Illustrated; or, An Essay Humbly offer’d towards proving the Purity, Propriety, and true Eloquence of the Writers of the New Testament. The title page further eleborates the arguments: in the first part, ‘those Divine Writers are vindicated against the Charge of barbarous Language, false Greek, and Solecisms’. The second part shows

Naming a discipline

By late in the 17th century, the plural noun with a definite article, ‘the Classics’, begins, infrequently, to mean both texts written in antiquity by non-Christian ancient authors in Latin and ancient Greek, and the authors of these texts. The 17th-century examples, however, remain few. The earliest we have identified appears when a schoolmaster writes to an implied specialist audience of teachers. His book is a guide to Latin syntax published in 1679, authored by one Jonathan Bankes. The author’s intention was to simplify the famous 16th-century Latin grammar of William Lyly: the full title is Januae clavis [‘Key to the door’] or, Lilly’s syntax explained its elegancy from good authors cleared, its fundamentals compared with the Accidence, and the rules thereof more fitted to the capacity of children. In the preface, Bankes explains the system he has used for explaining the different types of verb: ‘The Rules … are explain’d by adding the Verbs … whose variety is shewn, and whose difficulties are cleared by contracted sentences out of the Classics’.22 So there it is, although of course ‘the Classics’ here means authors or books in classical Latin rather than both Latin and Greek.

By 1684, at least in educational contexts, ‘the Classics’ can mean ancient authors or texts including Greek ones as studied by well-to-do junior males. That year, a translation of Eutropius’ Breviarium historiae Romanae was published, and its authorship credited to ‘several young gentlemen privately educated in Hatton-Garden’.23 Hatton Garden was a new residential development off Holborn, with splendid houses, favoured by the rich wishing to flee the squalor of the old city after it had succumbed to a bout of plague in 1665 and been ravaged by the Great Fire of 1666. The Eutropius translation, apparently the first into English, served as an advertisement for their school. It was prefaced by a poem entitled ‘To the ingenious translators’, and praising their efforts, by the Irish poet Nahum Tate (whose adaptations of Shakespearean plays were currently all the rage in London): ‘Auspicious Youths, our Ages Hope, and Pride, / Exalted minds’. Tate praises their teacher while regretting his own less happy experience of reading ancient authors: he had been

Later in the poem he recommends that they read not only Cicero but Demosthenes.24

The prose preface to this fascinating volume is by the Hatton Garden schoolmaster, Lewis Maidwell (1650–1715), one of Dryden’s correspondents. It is dedicated to John Lowther, 2nd Baronet of Whitehaven in Cumbria, who spent some of the vast income he derived from the coal pits there on sending his two sons to the school. They were amongst the translators.25 Its list of excellent things the boys may find in ancient authors includes material which shows they might expect to study Homer, Plutarch and Dionysius of Halicarnasssus, who is quoted, briefly, in Greek. Maidwell argues that England is lacking a system of education for boys which is making sufficient use of their intellectual potential: if more fathers took their sons’ education seriously, ‘the sleepy Genius of our Nation would rouse itself … Your nice assistance in Education well imitated, might adorn our Country within itself, and save many the trouble of dry-nursing their Youth abroad’. He specifies France and Italy.26

Yet the impact of French scholarship can be seen at work even in Mr Maidwell’s school for proudly English boys. This translation was published the year after the Delphin edition of Eutropius, the work of Madame Dacier.27 The 25 Delphin volumes of Latin texts, with Latin commentary by 39 scholars, were commissioned for Louis, le Grand Dauphin, beginning in 1670. The editions were masterminded by the duc de Montausier, the dauphin’s governor, and the Jesuit-trained scholar Pierre Daniel Huet, with a team including both Anne Dacier and her husband André. They transformed educational practice and intellectual life across Europe.28 One of the authors published early in the series, in 1681, three years before Maidwell’s students’ Eutropius, had been Aulus Gellius himself.29

The impact of the Delphin series can be seen from a different, comic perspective, in 1712. Richard Steele published a satirical article in the Spectator containing what he claimed were letters he had recently received from two schoolboys. One of them, a 14-year-old, complains that his father, although wealthy, does not think that training in ancient authors will do his son any good, and will not buy him the (expensive) books he needs to further his studies of Latin authors: our teenager laments, ‘All the Boys in the School, but I, have the Classick Authors in usum Delphini, gilt and letter’d on the Back’.30 By 1712, acquisition of the famous French ‘Delphin Classics’ series had become indispensable to what was beginning to be called ‘a classical education’.

They remained so until 1819, despite the launch of rival series,31 when they were superseded by the new series of well over 100 leather-and-gilt volumes of The Latin Writings after the system of the Delphin Classics, with Variorum Notes, masterminded by the entrepeneurial Abraham J. Valpy, who hired editors including George Dyer (see below pp. 169–71). By this time, some regarded the Delphin editions as allowing boys to ‘cheat’ insofar as they contained easier Latin paraphrases in the margins. Valpy used texts from diverse sources, added his own critical apparatus, and combined information from the Delphin editions with updated matter from other series. In Hardy’s Jude the Obscure, Jude Fawley’s attempts to teach himself Classsics draw on Hardy’s own experience as the son of a rural stonemason who struggled to further his classical education while apprenticed to an ecclesiastical architect.32 In chapter 5, Jude is given a decrepit horse and a creaky cart to deliver bread near Marygreen. He sits with a dictionary on his knees, and a crumbling Delphin edition of a Latin author, Caesar, Virgil or Horace, which he could just about afford

A key agent in shaping the early 18th-century fashion for the classical curriculum, when the Delphin Classics were cutting-edge, was Henry Felton, in his A Dissertation on Reading the Classics, and Forming a Just Style, written in 1709 and published four years later. Felton had been educated at Charterhouse and St. Edmund Hall, Oxford. He wrote the work as domestic chaplain to the Duke of Rutland, and dedicated the work to his pupil, John, Lord Roos, later the third Duke. It embeds its recommendations for imitating the example of the classic writers not only in style but in the morality of the great men they portrayed and the distinctive new vocabulary surrounding the new 18th-century concept of the gentleman: civility and politeness.34

The book cites the rhetorical handbooks of Cicero, Quintilian, Longinus and Aristotle as its ancient forerunners, but places itself at a particular time and place in its advocacy of the Classics. It celebrates the Duke of Marlborough’s successes in Belgium and France; it talks at length about the need for a new, politer, more civil style of speaking and writing than had prevailed in the Restoration period. It insists that all education needs to be subservient to the duties of the Christian religion, but also that ‘humane’ education can be immeasurably enriched by the study of the Classics:35

Felton’s pedagogical handbook was popular for the next 40 years, running into 5 editions and numerous reprints, playing a seminal role in the establishment of the Classics as the polite and refined curriculum for any aspiring gentleman.

A curriculum for gentlemen

By 1715, socio-economic class appears in discussions of the correct content of education for a gentleman, for example in The Gentleman’s Library, Containing Rules for Conduct in All Parts of Life: the author answers the hypothetical objection that ‘the refin’d Education’ he is recommending ‘is calculated but for One Class of People: That I have accommodated my precepts to the Rich alone, and neglected to sute them to the Children of the Plebean’. He answers that every father should ‘consult his Fortune and Circumstances’ and Cut his Coat according to his Cloath’.36 The volume assumes a classically educated reader: its Latin and Greek quotations from a wide range of authors are often untranslated.

The modish new syllabus prompted many publishing ventures. John Pointer’s new textbook Miscellanea in Usum Juventutis Academicae of 1718 provided everything a schoolmaster might need—instructions for ‘Reading the Classick Authors’, ‘A Chronology of the Classick Authors’, ‘A Catalogue of the Best Classick Authors and their Best Editions’, information on pagan mythology and Latin exercises. The maturing discipline in turn prompted the publication of a new genre of book designed to help the teacher in his tasks. These involved not only the grammatical, syntactical and rhetorical explication of the texts but also the classroom discussion of the myths, religion and geography to be found in them and occasionally even their aesthetic value and material objects and artworks which could illuminate them.37 And, by 1736, we find the term ‘class’ in its modern, socio-economic sense being used alongside ‘Classics’. It occurs in a polemic questioning the point of asking boys to spend such a large proportion of the hours available for education on acquiring proficiency in the ancient languages, when reading relevant material, such as newspapers, had a more obvious application to the aspiring businessman.38

This adventure in lexical history leaves us with a question: why did Classics/the Classics acquire its new name, identity and function in this precise period of British history, when a new ruling order was being created?39 One factor is that education was being discussed with a new self-consciousness. The thinkers influential in the 18th century were united in stressing the importance of education, whatever their views of what its contents should be, from Locke to Rousseau, Shaftesbury to Johnson. But British educators, while imitating the French, were also keen after the Glorious Revolution to distinguish the new Anglican gentlemanly classical curriculum from the Continental model, especially the French one. The French querelle between the ancients and the moderns was transformed to suit local English literature,40 and the rise of the Classics and Dryden’s translation of Virgil are inseparable from that cultural dispute. There was also a debate on whether boys should be educated at home or at school. The Spectator’s educational expert, Budgell, found Locke’s preference for home-schooling unrealistic.41 Swift strongly favoured school education.42 Even the über-aristocrat Lord Chesterfield sent his son to Westminster for three years. But the most significant factor was socio-economic: the rise of a new Whiggish mercantile segment of the ruling class. This process, which was beginning to transform Britain, is often subsumed by historians under terms like ‘emergence of the bourgeoisie’: it entailed the appearance of the anonymous-exchange market and the evolution of what Jürgen Habermas defined as the ‘bourgeois public sphere’ (bürgerliche Őffentlichheit), accompanied by an explosion in printed communication and accelerating urbanisation.43

Most importantly, the Whiggish sons of tradesmen and the Tory sons of hereditary nobles were increasingly being schooled together.44 Classics emerged to provide a curriculum which could bestow a shared concept of gentlemanliness upon them all. The 18th century saw exponential growth in private boarding schools, mostly small and run by Anglican priests, offering a classical curriculum aiming to provide the patina of gentlemanliness and access to Oxford and Cambridge.45 In early 17th-century England, the sons of gentry had often been educated beside merchants’ children at town grammar schools, but after the Restoration they were educated at home by tutors, or sent to one of the tiny group of richly endowed public schools.46 Divisions had become very visible in education. A fresh tone and model of manliness was required for the new and heterogeneous audience after the Bill of Rights 1689.

A new species of gentry among the merchant sector bought land and wanted prestige and a high ‘class’. In this context of the contestation of status and social mobility, substantial wealth had become attainable by a wider sector of the literate population and they wanted cultural capital and the status of gentlemen to match:

And once they had made it, they usually began to exclude those who had not, to ensure themselves safe positions high up the social hierarchy.

The process whereby youths from landed and mercantile families are fused into a collective of gentlemen by reading Classics is literally enacted in the Reverend Thomas Spateman’s three-part play for use in schools, The School-Boy’s Mask (1742). This traces the careers of a group of men, born into aristocratic, professional and business backgrounds, from their schooldays to old age. The boys who don’t read their Classics at school or in young adulthood (Rakish, Tinsel, Wild-Rogue, Fondler) become boorish louts who mix with prostitutes, acquire debts and die miserable early deaths in drunken squalor and poverty. The aristocrat who models himself on the heroes of Plutarch and Cornelius Nepos (Lord Grand-Clerck) founds a charitable infirmary and is rewarded with a dukedom. Bookish and Goodwill excel in Oxbridge classical studies and eventually become a Bishop and Lord Chancellor, respectively. Even their less talented friend, Rival, by working hard at his classical books and eschewing vice, lays the foundations of a successful career as a Doctor of Medicine.48 The moral of the tale is brought out most explicitly by Lord Grandclerck, who says that classical education, the qualification of the true gentleman, needs to be difficult. The entrance to the ‘delightful Land’ of Learning is surrounded by thorns, ‘to keep off the great Vulgar, and the small;’ its fruits ‘are too delicious to be gather’d by those who are not willing to be at some Labour to obtain them’.49

The concept of the gentleman was ambiguous. It might denote status, moral behaviour, or wealth (but only if invested in landed property); at other times the focus was refined manners and the good taste and ‘polite’ education becoming inseparable from education in the Classics.50 In his 1742 novel Joseph Andrews, Henry Fielding directly asks whether a low-born man with a noble character and refined education was not as admirable as one who was genteel by birth: ‘But suppose, for argument’s sake, we should admit that he had no ancestors at all … Would not this autokopros have been justly entitled to all the praise arising from his own virtues?’51

It emerges that it was only for the sake of argument that this possibility has been raised. Joseph is refined in conduct and principled, but can never, as an autokopros, become a gentleman. The term autokopros (never instanced in ancient Greek), invented by Fielding and glossed by him as ‘sprung from a dunghill’, links failure at gentlemanly status with a failure to know the ancient Greek language. Only someone who knew Greek could be familiar with the term he is imitating, autochthōn, the Athenians’ own title glorifying the antiquity of their bloodline and its intimate relationship with the land they occupied. So only someone who trained in the gentlemanly classical curriculum could even understand why Joseph Andrews could never be a true gentleman after all.

In the 18th century, ideas about good breeding, honesty and good character were scrutinised in fiction as they shaped the revised concept of the ‘Gentleman’ as intimately bound up with education in the Classics, and thus different from the gentlemanly consummate courtier of the Renaissance.52 Samuel Richardson’s Sir Charles Grandison (1753) ‘is a systematic attempt to devise every conceivable kind of situation in which an English gentleman may be called upon to display his gentlemanliness’,53 an aim which Richardson explicitly formulated in his preface. Fielding portrays depraved town gallants and brutal country ‘gentlemen’, but set against them a range of middle-class heroes—Parson Adams, Dr. Harrison, Squire Allworthy—whose moral characters, civility and kindness qualified them, even if they were not highborn, for the soubriquet of ideal gentlemen. Both Smollett’s titular heroes Roderick Random and Peregrine Pickle desire to establish themselves as gentlemen, in novels where the author fulminates ‘against the depravity vulgarity and sycophancy’ of the born-and-bred upper classes of both Bath and London.54

From 1711 onwards, Addison, along with his collaborator Richard Steele, influenced the idea of the gentleman profoundly. Addison wanted The Spectator to proselytise for good breeding and for ‘wit tempered with morality’, ‘effective among all the different sections of a rapidly growing middle class, as well as among the established upper class’.55 He targetted the whole male reading public, including longstanding rivals and antagonists—men of the court, the town, the city and the country. These values were discussed and promulgated in public coffee houses and private clubs.56 Simultaneously, the idea of taste emerges—a strange fusion of the aesthetic and the ethical, but tied to new forms of consumerism, including the book trade, the burgeoning entertainment industry,57 the grand tour and the taste for the antique in architecture and internal décor. The 18th-century passion of the titled and rich for collecting classical or al’antica sculptures to grace their Palladian and neoclassical interiors, gardens, and alcoves was partly ‘self-conscious expressions of refinement on the part of the owners, consistent with Lord Shaftesbury’s idea of civic humanism: that to be truly virtuous one must display such refinement to spur like-minded individuals to honourable action’.58 The visual arts of the ancient world were accessed in Britain through new compendia of prints, such as Domenico de Rossi’s Raccolta di statue antiche e moderne (1704) or Jonathan Richardson’s An Account of Some of the Statues, Bas Reliefs, Drawings and Pictures in Italy (1722), which served as a handbook for well-off grand tourists for centuries.59

People’s Classics at the London Fairs

By the first decade of the 18th century, therefore, the study of ancient Roman and Greek authors had acquired the title by which we know it today, a set of desirable textbooks, and a status and role as the basis of the intellectual, cultural and moral education of the English (from 1707 the British) gentleman. This accompanied a new taste for the antique in other spheres than education. But the Classics were also being accessed differently, by city-dwellers of all social classes, in popular entertainments, some of which had transparently subversive overtones in terms of their celebration of working-class identity and self-fashioning. In particular, the working classes of London were given access to rowdy versions of canonical classical epic at their summer fairs.

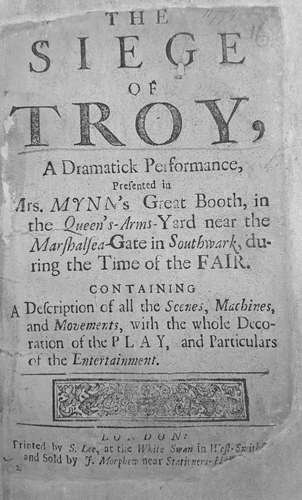

The painted board at the centre of Hogarth’s famous ‘Southwark Fair’ (painted in 1733 and engraved in 1734 or 1735) reads ‘The Siege of Troy is here’ (Figure 2.3). Hogarth had always been interested in the way that classical culture could be commodified. He opens his memoirs with the sad picture of his father, a classical scholar of repute, plunging his family into poverty after the failure of his project for a Latin dictionary.60 Fairground theatre was a better business prospect. The show Hogarth portrays, performed amidst other colourful entertainments, was Elkanah Settle’s ‘droll’, The Siege of Troy;61 the woman just left of centre ‘drumming up’ business is either Mrs Mynn, the entrepreneurial show-woman who produced it, or her daughter Mrs Lee. In the droll, the Trojans, led by a plebeian cobbler named Bristle, survive the siege of Troy and hold a carousal. It was a favourite at the London Fairs from its première at Bartholomew Fair, probably in 1698, until at least 1734, when it was performed by two different companies—one of them using puppets—at Southwark Fair.

Settle had been a successful playwright. His productions had included a Restoration drama on a Herodotean theme, Cambyses (1666).62 But he fell out of favour and shortage of funds drove him to accept the post of London ‘City Poet’, responsible for producing the pageants of the Lord Mayor’s Show.63 City pageants and fairground theatricals had much in common, besides their outdoor setting. The Lord Mayor’s Show was traditionally held on October 29th. Contemporary sources speak of cartoonish images of faces stuck on windows, candle-lit balconies, and waves of soldiers, clowns and Company men in livery—vintners, brewers, butchers and apothecaries—jostling to take precedence in the procession, carrying symbols of their crafts.64 Mumming and colourful costumes abounded: preparations for one of Settle’s shows are described thus in 1705 by the satirist Thomas Brown:

Dead cats and joints of meat were hurled. Caged lions were displayed at the Tower and mad people at Bedlam. The mob could become riotous.66 The atmosphere was similar to that of Bartholomew Fair, in the early 1700s still the largest fair. Its ancient function—to serve as a textile market—had largely been replaced, reports the eye-witness, by ‘rioting and unlimited licence’. He describes ‘the rumbling of Drums, mix’d with the intolerable Squalling of the Cat Calls and Penny Trumpets … the Singeing of Pigs, and burnt Crackling of over Roasted Pork’.67 From the upper floor of ale houses visitors enjoyed a view of the booths, and the actors ‘strutting around their Balconies in their Tinsey Robes, and Golden Leather Buskins’; typical entertainments were rope-acrobats, sword-dancers, horse-vaulters, ‘monstrous’ freaks of nature (three-breasted women, three-legged cockerels) and performing dwarves.68

Fairground theatricals were a particular attraction since the two licensed theatres were closed during the fairs. As in Hogarth’s picture, the booths offered a variety of entertainments. Mrs Mynn (or Mynns/Minns) ran a troupe of strolling players who certainly performed at the Cock-Pit in Epsom in 1708 and claimed to have performed ‘at Windsor for the Entertainment of the Nobility’.69 It is unknown when they first worked with Settle, but Theophilus Cibber states that he was

The poet Dryden died on 12th May 1700. But he had lived to endure seeing Settle exploit the success of his own masterful translation of the Aeneid (1697), the publication of which had been nothing short of ‘a national event’.71 Settle’s Trojan droll premièred in 1698 or 1699. There are two versions of the first printed edition of 1707. They claim respectively that its text represents the version of this ‘Dramatick Performance’, presented in Mrs. Mynn’s Great Booth, ‘over against the Hospital-Gate in the Rounds in Smithfield, during the Time of the Present Bartholomew-Fair’ (i.e. in late August 1707) and ‘in the Queens-Arms-Yard, near Marshallsea-Gate in Southwark, during the Time of the Fair’ (i.e. in early September). (Figure 2.4.) But both texts have an identical preface ‘To the Reader’ informing us that The Siege of Troy ‘made its first entry now Nine Years Since in Bartholomew Fair’. The current production is the third, and has had so much money and labour spent upon it that it is not inferior to any of the ‘operas’ performed in the Royal Theatres.72

The Siege of Troy has been called the ‘most remarkable of the Bartholomew-Fair dramas which found their way into print’.73 Its spectacular effects were agreed to have exceeded those of any other spectacle.74 These effects, including the elephants, castles, temple and chariots, are carefully reconstructed from original sources in Sybil Rosenfeld’s pathbreaking study The Theatre of the London Fairs in the 18th Century.75 The script is fascinating in its subversive treatment of heroic epic and classical mythology. It enacts the Troy story as related in Aeneid II from the arrival at Troy of the wooden horse and the self-mutilated Sinon to the burning of the city and the Greeks’ departure. The aristocratic and divine characters speak rhyming iambic couplets as they do in Dryden’s Aeneid translation. Those from the Greek camp are Menelaus, Ulysses and Sinon; in Troy there are Paris, Helen, Cassandra and Venus. But a sense of how packed Mrs Mynn’s booth platforms must have become, as indicated in Hogarth’s depiction, is conveyed by the other 53 cast members listed under ‘Actors’ Names’:

The crucial element from the perspective of the droll’s socio-political impact is that ‘numerous Train of Trojan Mob’, whose identity as ‘Spectators of the Wooden Horse’ is shared with the external audience of the droll. Some of that Mob have sizeable speaking parts, and these characters, although nominally Trojan, come over as working-class city-dwellers indistinguishable from Settle’s own public.

In 1614, Ben Jonson had laughed at the taste for introducing such a contemporary frame to classical mythical stories in the puppet-show in the final act of Bartholomew Fair, ‘The ancient moderne history of Hero, and Leander, otherwise called The Touchstone of true Loue, with as true a tryall of friendship, betweene Damon, and Pythias, two faithfull friends o’ the Bankside’ (Act V scene 3).76 Rosenfeld concludes that the ‘populace could not be trusted to stand too much of the classical legend even though it was accompanied by scenic marvels; the comedians had to be brought on to amuse them with the rough and tumble life they knew’.77 But another way of looking at the fusion of past and present in the world created by the droll is as a complex metatheatrical response, in a cross-class context, to the elite connotations of the classical material. There are two collectives responding to upper-class antique heroics, the Trojans within the play and the Londoners in the audience. The boundary between them is jeopardised.

In the second scene we are transported to ‘Bristle, a cobler, and his wife’. These lower-class Trojans speak raucous prose. Mrs Bristle wants to go and see the wooden horse, but her husband Tom Bristle objects to her leaving the house:78

Fortunately for Mrs Bristle, the Trojan Mob enters and she escapes domestic violence. In a magnificent spectacle, Paris and Helen now appear riding in a ‘Triumphant Chariot’, drawn by elephants painted on the flats. Ten more painted elephants support ten castles crowded with richly dressed attendants, with a vista of Troy beyond. Paris and Helen admire each other in rhyming couplets. A crazed Cassandra enters to condemn the adulterous pair, before Venus descends in a swan-drawn chariot and the attendants sing a celestial chorus.79

In Act II, Ulysses and Sinon persuade the Trojan mob, now led by Bristle who has appointed himself their Captain, to breach the Trojan Walls and drag in the horse. Cassandra is distraught, and performs miracles designed to ‘preach bright Reason’ to Paris. The next spectacular scene ‘discovers the Temple of Diana’ at Troy, complete with eleven golden statues of the Olympian gods, including Diana, and a heavenly vista. When Paris and Helen arrive, Cassandra waves her wand, and the statues’ costumes miraculously turn black as the vista ‘is changed to a scene of Hell’. But only the audience and Cassandra can discern the truth of this transformation: Paris and the Priest see nothing altered, and agree that she is insane.80

The vertiginous alternation between heroic and demotic is underlined by the next scene change to a street in Troy. The Greek army, streaming out of the Trojan horse, disperses to begin its work of destruction; Captain Bristle and the Mob, unaware of the danger, enter for a night of revelry and fantasies of social levelling:81

As they carouse, the siege ensues, the Grecians setting fire to houses and abducting maidens. Menelaus slays Paris; Helen commits suicide by hurling herself into the flames. But the members of the Trojan Mob led by Captain Tom Bristle survive. Menelaus pardons them:82

The droll ends amidst revelry. Ulysses draws the moral that adulterous ladies endanger whole countries, a theme which has been reinforced by the extra-marital flirtations of Mrs Bristle.

The Siege of Troy is thus subversive on several levels. The blame for the Greek expedition against Troy is exclusively laid on the shoulders of Trojan royalty and the renegade Queen of Sparta. The royal culprits, Helen and Paris, both expire. The action ends with a Trojan working-class leader about to rebuild the city; this is radical enough in itself, but also repudiates the tradition of Troy’s annihilation asserted by the canonical classical authorities Virgil and Homer. The aristocrats’ rhyming couplets and elevated diction are deflated by juxtaposition with the indelicate dialogue of the Trojan commoners, who are given all the laughs. There is a further level of insouciance. Royal propaganda had associated William III with Aeneas, and his arrival on the sands of Torbay in 1688 with Aeneas’ arrival in Latium; Dryden’s publisher Jacob Tonson insisted on superimposing William’s features on those of Aeneas when he reproduced in Dryden’s Aeneid the engravings from John Ogilby’s 1654 translation.83 Settle omits Aeneas from his Trojan droll, thus avoiding offence to either Catholics or Anglicans amongst Mrs Mynn’s customers. But in 1698, by refusing to use Troy to pay homage to the King, he threw into further relief his rejection of Aeneas as hero of the tale and preference for the plebeian cobbler. Moreover, the invention of the identifiably London/Trojan hybrid Bristle gives a makeover to the familiar story of Brutus the Trojan who had founded London as the ‘New Troy’; the political message of a working class with a continuous identity and recreational culture (note ‘The Siege of Troy is here!’ in the present tense on Hogarth’s billboard) needs to be understood in the context of seven decades of serial changes in constitution and kings.

Settle’s rivals were aggravated by his ability to make money from the same material (and even stage properties) to different audiences. His generic versatility also challenged customary distinctions between ‘high’ and ‘low’ arts, especially when he had the temerity to publish, in addition to the text of the Opera, attractive souvenir volumes containing the script of the droll, adorned with a woodcut depicting Captain Bristle.84 But, as we shall see in Chapter 17, worse was to come. The Siege of Troy was turned into an even ‘lower’ medium than a fairground droll—an itinerant puppet show.

Whose Classics?

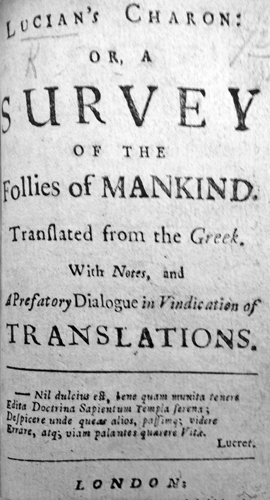

The new identity and desirability of training in the Classical languages, as an obligatory accoutrement of the Gentleman, had also, by as early as 1700, inspired an altercation between those who despised reading the classical authors in translation and those who advocated it. In this debate, the arguments anticipated by three centuries those put forward today in discussions about the best way to give the nation’s youth access to the ancient world. Thomas Brown, the first man to use ‘Classics’ without a definite article, and the author of the colourful description of the Lord Mayor’s Show quoted above, was also probably the author of a wonderful piece of English prose published in 1700, the ‘Preface’ to an anonymous book, Lucian’s Charon: or A Survey of The Follies of Mankind. Translated from the Greek. With Notes, and A Prefatory Dialogue in Vindication of Translations (Figure 2.5). The dialogue itself is one of Lucian’s most elegant little dramas: Charon ascends to the world of the living and is taken on a whistle-stop tour of archaic civilisation by Hermes. The 1700 preface, however, is an original dialogue between two men, Eumenes and Philenor, on the theme of studying classical literature in translation. The arguments put forward by Philenor are diverse and cogent.

Philenor has published a translation, thus disappointing Eumenes. Philenor points out that translation of Greek masterpieces was good enough for the Romans, since Cicero, Ennius, Pacuvius and so on had all been translators. But Eumenes is having none of it:

This is a curious case of putting the cart before the horse: we must not translate Greek and Latin into English because it has cost so much effort to learn those ancient tongues. Philenor sensibly responds that this does not represent an obstruction of learning. On the contrary, we ‘shou’d think now that nothing in the World has a greater tendency to its advancement. Those rich Treasures of Knowledge & Learning among the Antients are no longer now lock’d up in unintelligible Words’. Translating texts by the ancient Greeks and Romans into English

The patrician Eumenes plays the class card. If every man can read Plutarch and Cicero in his own native tongue, this will ‘make Learning common, cheap, and contemptible, when every ordinary Mechanick shall be as well acquainted with these Authors as he that has spent 10 or 12 Years in the Universities?’ At the climax of his rant against reading ancient authors in translation, he cites the same proverbial pearls cast before swine that Edmund Burke was to invoke 90 years later, quoted at the opening of this book:

Philenor points out that Eumenes looks upon

He quotes Montaigne to the effect when you observe the young men ‘when they are newly come from the Universities, all that you will find they have got is, that their Latine and Greek has only made ’em greater and more conceited Coxcombs than when they went from home’.88 And he triumphs when he argues that one of his aims has been to ‘excite’ the desire of readers to improve their knowledge of the ancient language.89 The pearls of ancient culture will not be besmirched by the swine forming the multitude. Whether consumed in fairgrounds or through mother-tongue translations, they just might edify and delight them instead.

Conclusion

By the end of the second decade of the 18th century, the battle-lines which still shape debates over Classics had been drawn up. Classics, along with the textbooks required to study it, had emerged as a product that could be purchased by any parent with the money to keep his son in education, rather than remunerative work, late into his teens. It did not matter whether the money was ‘old’ and related to land-ownership, or ‘new’ and related to colonial ventures or commerce, since the appearance of competence in Classics bestowed the status of a gentleman and a guarantee of his good taste and moral refinement. The length of time it took sometimes reluctant children and youths to acquire apparent competence in classical languages was central to its attraction, since proficiency in them obliquely drew attention to the financial prosperity, as well as the gentility and good taste of the family paying for the education. The issue of the usefulness of Classics to working life, especially business, was already raised; so was the fear—however faint—that enjoyment of Classics, if not controlled by an over-riding Christian faith, might have undesirable moral consequences.

But Britons who were not able or willing to bankroll their sons’ classical educations were already fighting back. The Greeks and Romans could be approached by other routes that did not require those years glued to grammars and dictionaries. They could increasingly be read in mother-tongue translations, by great poets like Dryden and Pope, even though this was obviously derided as a vulgar and inferior mode of access to the Classics by those who had purchased the veneer of a higher social class offered by the linguistic training. The material covered in ancient authors could be enjoyed even by the completely illiterate in accessible entertainments such as fairground drolls. These also provided the opportunity to laugh at the elitist associations of classical education, as well as the elevated subject-matter and style of much classical literature, and thus wage a form of cultural class war in the most pleasurable of contexts.