SIX

Into the Breach

German General Ludendorff’s plan for spring 1918 was not to capture Paris, but rather to demolish Allied armies before American forces could intervene on the battlefield. He hoped a bold stroke would conclude the war in Germany’s favor. On March 21, the Germans opened their spring offensive. They targeted the juncture between the English and French armies along the Somme River to drive a wedge between the two allies. The Germans had spent the winter retraining part of their army for “storm trooper” tactics to bypass strong points and break through enemy lines, just as the Russians had used in the previous year against Austria. They severely mauled the British Fifth Army and broke through to the open countryside.

The moment of crisis had arrived. The Allies requested American soldiers to take control of part of the front line. Pershing yielded to the emergency and allowed American units to be interspersed among Allied units wherever they were most needed, as his Christmas orders from Secretary Baker had allowed. The most combat-ready force was the 1st Division, which was shifted west by train to reinforce the French. Other units occupied quiet sectors of the front so French forces could join the main fight. Altogether, Pershing loaned the Allies 132,000 doughboys.1

The Germans lacked the ability to exploit their breakthrough on the Somme. If they had had tanks, their momentum might have fully cut off the British army, just as they would do at Dunkirk in 1940. But the Germans had no tanks, and their infantry could only travel so fast before outrunning artillery and supplies. British and French reinforcements arriving by train and truck managed to contain the breakthrough and drive the Germans partly back, ending their first offensive by April 4. But the crisis was far from over; in fact, the Germans had merely made their opening move.

Ludendorff believed that the British were the most vulnerable of all the Allies. All he had to do was drive their army into the English Channel. Ludendorff launched his second offensive against the British on April 9, achieving another breakthrough in Flanders, but one that was soon contained. The French heavily reinforced the British, making it more difficult for Ludendorff to finish off the British Expeditionary Forces. He would redirect his attention to the French army to peel off the reinforcements, then planned to resume the attack on the British once they were vulnerable again.

It took this emergency for the Supreme War Council to finally appoint an Allied commander in chief to make battlefield decisions for all of the armies. Given that the war had mostly been fought on French soil, the command fell to a Frenchman: General Ferdinand Foch. And given the high casualties that the British army had suffered, the Allies agreed to provide far more shipping to bring American doughboys over in huge waves. The million-soldier commitment the Americans had made soon doubled to two million. Pershing cabled back to Washington, “Send over everything you have ready as fast as you can. The responsibility for failure will be ours.”2 The British allocated more shipping to bring soldiers across the Atlantic, while American shipyards doubled their efforts to launch more ships. The pace of doughboys arriving in Europe had been slow, but now it quickened significantly, rising by several hundred thousand each month until the American Expeditionary Forces reached two million men in France. This tipped the manpower scales in favor of the Allies. The downside was that most of the soldiers were shipped out with only partial or even minimal training, and none of the doughboys were well armed. The Americans would rely on the Allies to provide heavy weaponry, including artillery and machine guns.3

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George expressed his frustration with how the Americans were building up their army. He was a leading advocate for “amalgamation,” allowing British and French forces to train and fight alongside the Americans, believing there was too little time to bring the doughboys to a combat-ready state. The Americans had been in the war a full thirteen months already and with little to show. Pershing refused to take advice from the Allies nor scatter his precious untested forces. “The result was that an amateur army was fighting a professional army,” Lloyd George complained with much justification.4

After mauling the British army in Flanders and along the Somme, Ludendorff uncharacteristically delayed his next offensive until late May, possibly because of high rates of influenza in the German army. During the lull, Pershing agreed to send the 1st Division into a limited battle to test its combat readiness—and to prove American resolve to fight. The target was the German-occupied town of Cantigny, a small salient that cut into Allied lines. The attacked was staged on May 28 and quickly captured the town. Colonel George Marshall, who fractured his ankle when his horse fell, described the battle: “The general artillery bombardment opened with a tremendous roar and Cantigny itself took on the appearance of an active volcano, with great clouds of smoke and dust and flying dirt and debris, which was blasted high into the air.”5 The Germans unleashed a furious counterattack, pounding the doughboys with heavy artillery even as the supporting French artillery pulled out to counter the latest German offensive. Still, the Germans failed to push the Americans out of Cantigny, and the 1st Division remained in the sector for the next two months. The 28th Infantry Regiment, which bore the brunt of the fighting, suffered more than 1,600 casualties in the three-day battle. One of the Americans who fell during the battle was author Willa Cather’s cousin, Lieutenant Grosvenor Phillips Cather, who was leading his men against a German counterattack. Another participant in the battle was Major Theodore Roosevelt, the former president’s son. He would later land in the first wave at Utah Beach on D-Day in 1944, dying a month later from a heart attack. Captain Clarence Huebner, who led an infantry company at Cantigny, commanded the 1st Division at adjacent Omaha Beach.6

Artillery was the big killer during the war, and as one historian noted, “The Great War was, in reality, the Great Artillery War.”7 The term “shell shock” was coined to describe the psychological and physical outcome from high explosives. George Marshall noted how shell shock would impact even the strongest soldier: “A 3-inch shell will temporarily scare or deter a man; a 6-inch shell will shock him; but an 8-inch shell, such as these 210-mm. ones, rips up the nervous system of everyone within a hundred yards of the explosion.” It left men trembling uncontrollably and sometimes comatose with a thousand-yard stare for hours or even days. Every man had a breaking point. Some men never recovered psychologically.8

As the Battle of Cantigny was unfolding, the Germans opened a new offensive against the French army on May 27. Thirty German divisions broke through the Chemin des Dames region and pushed toward the Marne River. If Paris was sufficiently threatened, the Allies would reinforce this sector, and Ludendorff could then concentrate on wiping out the English army in Flanders. In four days, the Germans drove the French back thirty miles and took 60,000 prisoners. They now had a foothold on the Marne, where they were turned back from Paris in 1914. They rapidly approached the river crossing at Château-Thierry.

Red Cross volunteer Isabel Anderson had just returned to Paris for some rest when the latest German offensive commenced. She packed her belongings into an overstuffed trunk. “Thinking I might never get a hot bath again, I took two, one at midnight, the other at three in the morning,” then departed at five after a brief rest.9 She and the other volunteers departed for the front, where they helped set up a hospital near Compiègne, northeast of Paris. “Just as soon as we were ready to receive the soldiers, they began to come in from the trenches. They were terribly shot to pieces, and many had head wounds, which were perhaps the worst of all.” The Germans were bombing Paris by airplane, and a giant artillery piece known as Big Bertha was trying to destroy a nearby railroad bridge. It was a scene of considerable excitement as the wounded poured in to triage. “From my window at the hospital I counted seven balloons hovering over the trenches, and saw airplanes constantly passing,” both French and German.10

Big Bertha, as it became known, was actually a half-dozen giant cannons that the German firm Krupp manufactured. They could lob artillery shells seventy-five miles, though not always accurately. “This gun was a marvelous product of technical skill and science,” Ludendorff wrote, who admired the gun’s ability to hit Paris from far away. “Part of the population left the capital and so increased the alarm caused by our successes,” he bragged. As the Germans advanced toward the Marne River, hundreds of thousands of French refugees fled toward Paris.11

German success meant another Allied crisis. The French lacked the reserves to stanch the German tide, and General Philippe Pétain called Pershing for help. Pershing yielded the 2nd and 3rd Divisions to confront the Germans at the apex of their advance. The 3rd Division took up a defensive position at Château-Thierry, the vital Marne River crossing, on May 31. A fierce battle ensued at Château-Thierry, with the Americans holding the south bank while the Germans continually attacked from the north. German artillery plastered the town, but doughboys took up positions in the rubble and, armed with machine guns, repulsed wave after wave of German infantry attacks. The German advance faltered and a seven-week stalemate resulted while both sides peered over the river from their respective sides of the wrecked town.12

While the 3rd Division held off the Germans at Château-Thierry, the 2nd Division moved into the dense Belleau Wood on June 4, just to the northwest, to close a gap in the French line. The 2nd was a composite division of regular army and marine brigades. Commanded by General James Harbord, the Marine 4th Brigade pushed into the thick forest and engaged the Germans. They had little artillery support, so the battle was a straightforward infantry fight with rifles, bayonets, hand grenades, and machine guns. Embedded American journalist Floyd Gibbons accompanied the marines into the hellish forest and recorded the most famous line from the battle when Gunnery Sergeant Dan Daly led his platoon forward on a suicidal attack across an open field, shouting, “Come on, you sons-o’-bitches! Do you want to live forever?”13 The marines eventually drove the Germans out of Belleau Wood after five weeks of horrific fighting. More than five thousand marines became casualties in the fierce battle, which had taken on four German divisions. The French renamed Belleau Wood as Bois de la Brigade de Marine. The high casualties revealed flaws in Pershing’s open warfare doctrine, as many casualties could have been avoided if the marines had proper artillery support.14

Gibbons was shot twice and suffered a compound fracture to his skull at Belleau Wood. He recovered in a hospital ward with fourteen soldiers from a wide range of ethnic backgrounds. “There was an Irishman, a Swede, an Italian, a Jew, a Pole, one man of German parentage, and one man of Russian extraction,” he wrote. “Here in this ward was the new melting pot of America . . . They are the real and new Americans—born in the hell of battle.”15

With the German offensive and American concentration near Château-Thierry, Billy Mitchell brought his aircraft brigade to assist in the battle from above. They faced off against the best fighter pilots the Germans had, including the Flying Circus, the famed squadron once led by the famed Red Baron, Manfred von Richthofen. (Richthofen was shot down and killed over the Somme on April 21.) The Germans flew in large formations of Fokker fighters that dominated the skies, while the more inexperienced Americans flew the obsolete Nieuports. Mitchell desperately asked for the more modern, nimble Spads to take on the faster Germans. His command suffered a heavy loss of pilots, including Theodore Roosevelt’s youngest son Quentin, who was shot down over German lines on July 14. The following month, the French began equipping the American squadrons with Spads.

The Germans gave the young Roosevelt a funeral with military honors, and a photographer forwarded a photograph of the plane wreckage showing Quentin’s lifeless body. It might seem a morbid gesture, but it was sent out of respect for the former president so that he and his family would know that Quentin had served and died honorably—and that he was killed instantly. The former president was devastated at the loss of his youngest son. His own health rapidly declined in coming months.16

The American air service focused on pursuit aircraft. It had a few bombers as well, though they were not well equipped or well led. A squadron of six American bombers led by Major Harry Brown took to the air on July 11, got lost, landed at a German airfield, and were captured. The Germans dropped a cheeky message on an American aerodrome, “We thank you for the fine airplanes and equipment which you have sent us, but what shall we do with the Major?” Mitchell came to rely on British, French, and Italian bombers instead.17

In one month, the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Divisions had taken part in some of the heaviest fighting of the war and held their own against the Germans. Though the Americans had lacked experience and suffered high losses, they proved their fighting mettle. Pershing reinforced his bloodied frontline soldiers with two divisions, the 26th and 42nd, forming the 1st Corps under Hunter Liggett facing the German salient on the Marne River that now bulged toward Paris. It was the first step toward an independent American army in France.

Ludendorff launched his final offensive on July 15—the day after the French Bastille Day holiday—in an attempt to break out of the Marne salient and capture Reims. It became known as the Second Battle of the Marne. The French 4th Army was expecting it and had made significant defensive preparations. The German attack east of Reims was halted with heavy losses, but west of the city they crossed the Marne River on pontoon bridges and briefly broke through French lines before reinforcements contained the advance. About 85,000 American troops hurriedly reinforced the French. In the path of the German advance now stood the American 3rd Division, which held Château-Thierry and a key ridge overlooking the Marne River crossings.

Hearing that the Germans had commenced their offensive, Colonel Billy Mitchell took to the air personally to scout the front line. It was a cloudy day with a low ceiling, forcing him to stay close to the ground, but fortunately he did not run into German pursuit aircraft. He flew along the Marne, following the river’s course when suddenly a great volume of German artillery fire landed on the south bank, which the 3rd Division was defending. He flew in closer and discovered five bridges that the Germans had thrown over the river. Columns of infantry were marching across. “Looking down on the men, marching so splendidly, I thought to myself, what a shame to spoil such fine infantry,” Mitchell wrote.18 But this was war. Landing at his aerodrome, Mitchell ordered his brigade of pursuit aircraft to take to the air and strafe the German infantry. The French sent bombers to hit the pontoon bridges. The 3rd Division held its position, blunting the German offensive, and earned its nickname, “Rock of the Marne.”

Three days into the latest German offensive, Ferdinand Foch, the supreme Allied commander, marshaled forces for a counterattack on the German Marne salient. The American 1st and 2nd Divisions, along with a French colonial division, were placed on the vulnerable western part of the German bulge. They were to counterattack directly into the salient, their goal to take Soissons, a vital supply route. Their attack was to begin on July 18. The 2nd Division had trouble assembling, as the roads were so crowded with vehicles that they could not reach the area until the middle of the night, and numerous units got lost in the dark. Colonel Paul Malone, commander of the 23rd Infantry Regiment, got the men to the front with the help of his entire staff and a French regiment’s runners. Many men did not reach the front until after the artillery bombardment began, and they had no opportunity to reconnoiter: they simply went straight into the battle. Malone noted, “The Second Battalion leading the attack had gone over the top at H hour (4:35 A.M.), but to reach its position it had been necessary to advance during the last ten minutes at a run, the men reaching the jumping-off trenches breathless and exhausted.” The Americans were in luck: despite the lack of reconnaissance, their attack smashed through the German line. The Battle of Soissons took the Germans by surprise.19

Over the next four days, and Americans advanced seven miles and took thousands of prisoners, but at a high cost. The 1st Division suffered 7,500 casualties, while the 2nd Division—only engaged on the first two days of the counterattack—had 5,000 casualties. The attack threatened the German supply lines, and Ludendorff not only halted his final offensive, but also began evacuating the Marne salient.20

Fifty-three years earlier, General Ulysses Grant had attacked Robert E. Lee’s army at Cold Harbor and in a single afternoon lost 7,000 men. The 1st Division’s casualties at Soissons were greater than the entire Union Army had experienced at Cold Harbor. Colonel George Marshall was saddened at the horrific combat losses. All of the division’s colonels, except for three, had been killed, and every battalion commander was a casualty. These had been Marshall’s friends.21 The Battle of Soissons was so costly in part because of Pershing’s open warfare doctrine. It was too reliant on riflemen attacking with limited or no artillery support. Time and again the inexperienced doughboys charged machine gun nests frontally, positions that artillery could have eliminated. The result was unnecessarily high casualties.

The Battle of Soissons was a victory for the Allies and proved the turning point of the war. They had seized the initiative from the Germans, who would never regain it. Ludendorff advanced reinforcements to prevent the Marne salient from collapsing, and in turn the Germans canceled their planned attack on the British in Flanders, as they had deployed their reserves. The last German offensive had ended. Chancellor Georg von Hertling said, “We expected grave events in Paris for the end of July. That was on the 15th. On the 18th even the most optimistic among us understood that all was lost. The history of the world was played out in three days.” Hindenburg wrote how it dashed the Central Powers’ hopes: “The effect of our failure on the country and our allies was even greater, judging by our first impressions. How many hopes, cherished during the last months, had probably collapsed at one blow!”22

By early August, Franco-American forces had pushed the Germans out of the Marne salient and back to their starting point, the Hindenburg Line. The Second Battle of the Marne was a clear Allied victory but a costly win: some 300,000 American troops were engaged in the fight, and more than 50,000 were casualties. But even more important, the German army was spent. Morale plummeted as soldiers grew tired of the fighting, the poor rations, life in the muddy trenches, and propaganda aimed at them to go home—or to make common cause with the Bolsheviks. With a growing number of American soldiers in France, the Allies seized the initiative to drive the Germans from France. Pershing’s dream of fielding an independent army under American command would soon become a reality. The spring crisis for the Allies was finally over—but for the Germans, their crisis was just beginning.23

While Ludendorff evacuated the Marne salient, the Australians and Canadians struck back against the denuded German lines along the Somme River on August 8, completely surprising their foe. British Field Marshal Douglas Haig executed a brilliant combined arms operation at Amiens that penetrated deep into German lines, demolished six German divisions, and took thousands of prisoners. Ludendorff called August 8 the “black day of the German Army.” He realized that the army’s losses and morale had declined to a point beyond salvaging. Germany had lost the war, even though the soldiers were still fighting.24

The Influenza

Another enemy was lurking that would kill millions, one even deadlier than German machine guns: the 1918 influenza pandemic. With conscription, millions of young men were brought together in cramped barracks. The close proximity became a breeding ground for infectious diseases. Measles struck the U.S. Army in late 1917, killing 5,741 soldiers from secondary infections, mostly pneumonia. But this paled in comparison to one of the deadliest pandemics that would ravage the world: the so-called Spanish flu.25

The influenza probably began in Haskell County, Kansas, in January 1918, then soon spread to Camp Funston (now part of Fort Riley) in March. It quickly overwhelmed the camp, and the contagion soon spread to other military bases when soldiers were transferred. Nearby cities and towns witnessed people falling sick as well. From there, soldiers carried the flu aboard ships to France. The British, French, and German armies soon had it. When the King of Spain got sick, newspapers reported on the illness, and since Spain was not at war, their press was not censored. The flu took on the name history assigned it: the “Spanish influenza,” though it did not originate there. The virus moved quickly, but this initial variation was not deadly. Most people recovered after three days.26

Viruses are constantly evolving, and this particular strain of influenza mutated into a far deadlier pathogen over the summer. In fact, the worst period for the flu was during the final phase of the Great War, from mid-September to December. This lethal strain first appeared at Camp Devens near Boston. People suffered severe headaches and bodily pain. Bodies turned blue like they were being strangled, while victims coughed up blood and their eardrums ruptured. Many became delirious. The deadly influenza could kill someone in half a day. The flu was especially lethal for young adults, whose vigorous immune systems filled their lungs with fluid and white cells, resulting in a higher number of deaths from pneumonia.

The influenza struck terror. People isolated themselves and avoided human contact. Those who ventured outside wore gauze masks that proved useless: they still got sick. Influenza hit the cramped steel mills and shipyards hard, and many others stayed home to avoid catching the contagion. The dead overwhelmed hospitals and morgues, and there was hardly a house in the country that did not have a sick person in it. Cities ran out of coffins. Some resorted to mass graves to bury the dead, the trenches dug by steam shovels. Troop transports witnessed crew and passengers reeling from the pandemic. Many ships buried scores of the dead at sea. The September draft was to call up 142,000 men, but authorities postponed it because the cantonments were too full of sick soldiers.27

Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt went on an inspection tour of Europe in summer 1918, visiting battlefield sites and naval facilities. He returned to the U.S. in September on the Leviathan. Like many on board, he caught the influenza and was deathly ill with double pneumonia, such that he was carried off the ship on a stretcher when it reached New York. Once he returned to the family’s Hyde Park residence, his wife Eleanor unpacked his suitcase and there found a bundle of love letters from Lucy Mercer—Eleanor’s former social secretary—to Franklin. FDR had been having an affair with the woman for two years. It devastated Eleanor. Faced with the threat of divorce and the end to his political career, Franklin stayed with Eleanor, but the intimacy in their marriage was over. They continued as political partners.28

Influenza struck the nation’s capital with a vengeance in fall 1918. Thousands were sickened, and authorities banned public gatherings, including church services and concerts, knowing that the disease was highly contagious. Still, hospitals soon ran out of space—and morgues soon ran out of coffins. Gravediggers were in short supply as well, since people were fearful of coming into contact with those who had died from the flu. Herbert Hoover noted that the influenza epidemic struck the Food Administration hard: half of his employees got sick, and many of them died. About 3,500 people in Washington, D.C. died from influenza.29

And then abruptly in December, shortly after the war ended, the virus began to weaken. The death count dropped. A third wave of influenza would strike as the virus mutated again, but it was not nearly as deadly. President Wilson would fall ill to this wave in April 1919 at the Paris Peace Conference. People continued getting sick into 1920 and even beyond, though the virus was losing its virulence.

The influenza of 1918 killed at least twenty-one million people worldwide, more than the combat deaths from the Great War. Later estimates ranged from fifty to one hundred million deaths worldwide. In the U.S. alone, an estimated 675,000 people died from the flu. The influenza was the deadliest plague in human history.30

Hemingway’s War

The United States had just entered the war when Ernest Hemingway graduated from high school in the Chicago suburb of Oak Park. After a short stint working on a farm, he went to work as a cub reporter for the Kansas City Star. Hemingway wanted to serve in the war, but he had terrible eyesight and was only eighteen, so could not be drafted. In March 1918, he enlisted as an ambulance driver in Italy. If the U.S. Army would not have him, the American Red Cross would.

Hemingway traveled to New York to await transport to Europe. He was issued a full set of uniforms and was commissioned a lieutenant. Hemingway explored Manhattan with his friends in uniform—a proposition that soon became tiresome, as he wrote his family: “We thought at first it would be fun because all privates and non commissioned officers have to salute us. But by the time we had returned about 200 salutes it had lost all its fun.”31

On May 18, 1918, President Wilson was to review a Red Cross parade in Manhattan, but instead he decided to lead the parade, marching at the head of 70,000 people down Fifth Avenue. The New York Times fairly gushed about the president: “For the thousands of the city who had never seen the President, this was an opportunity for which their gratitude yesterday knew no bounds.” Among the participants marching in that same parade was young Hemingway.32

Hemingway was strikingly handsome and a talented wordsmith, and he was always falling in or out of love with a woman. By the time he shipped out to Europe in May, the eighteen-year-old was broke, having spent $150 on an engagement ring for a girl he would never marry. However, he would eventually have four other wives.33

Hemingway briefly made his first visit to Paris—a city he would return to after the war and would forever be associated with—before being sent to Italy to his assignment, an American hospital in Milan. On his first day he helped retrieve body parts from a munitions plant explosion that had killed thirty-five people, mostly women. He would later describe the incident in his 1932 book, Death in the Afternoon: “I remember that after we searched quite thoroughly for the complete dead we collected fragments.” In June 1918, he met a Red Cross ambulance driver, John Dos Passos, a fellow Chicagoan and writer he would befriend after the war.34

Hemingway quickly grew bored at the hospital and asked for a transfer to a Red Cross canteen closer to the front. Even that was not close enough to the action, so he began delivering chocolate and cigarettes to the Italian troops in the trenches, riding to the front on a bicycle. The Italian troops referred to the smiling young man as the giovane Americano—the young American.35 He wrote a high school classmate, describing the sound of artillery and mortar shells. He was “sitting out in front of a dug out in a nice trench 20 yards from the Piave River and 40 yards from the Austrian lines listening to the little ones whimper way up in the air and the big ones go scheeeeeeeeek Boom and every once in a while a machine gun go tick a tack a tock.” He was amazed that he had graduated high school just a year earlier.36

One July 8, one of those mortar shells nearly landed on him. An Italian standing between him and the shell was killed, while another nearby had his legs blown off, and a third soldier was badly wounded. More than two hundred shell fragments peppered Hemingway’s legs, and he was also shot twice. For this the Italians would award him the Silver Medal of Bravery.37

Hemingway was the first American to be wounded in Italy, a fact that made him particularly proud and earned him much notoriety in the press. He faced a long recovery in the hospital and multiple surgeries, and it took months before he was able to walk again. While he was in the hospital, he fell in love with an American nurse, Agnes von Kurowsky, a blond beauty who was seven years older than him.38

After completing his convalescence, Hemingway returned to the States in January 1919 after nine months away. He continued writing Agnes, who remained in Italy as a nurse, planning their life together. However, she wrote him in March 1919 to say that she no longer loved him and was engaged to an Italian officer. Hemingway was heartbroken. But he would also rebound and marry his first wife, Hadley Richardson, in 1921 and they would decamp for Paris. He would write about his affair with Kurowsky in his 1929 novel A Farewell to Arms.

The Allied Fall Offensive

French Marshal Ferdinand Foch had seized the initiative from the Germans in summer 1918. He was now faced with a significant choice: continue the offensive or wait until more trained American troops were on hand. By the following summer, the War Department planned to have eighty American divisions in Europe, numbering 3.2 million soldiers. A tidal wave of doughboys was coming, and after sufficiently training the rookie soldiers, the Allies could prepare for a knockout blow to Germany in 1919.39

That was one option. The other, riskier option was to continue the offensive with the troops that were on hand, including the partly trained American Expeditionary Forces. It was a gamble to begin an offensive in the fall, as the weather would no doubt turn foul. But there were political benefits as well: Germany’s allies were abandoning ship, and the French knew that German morale was low. Likewise, the Allied populations were weary of the war and wanted peace. As thousands more partly trained American reinforcements arrived in France each day, Foch deemed it time to strike.

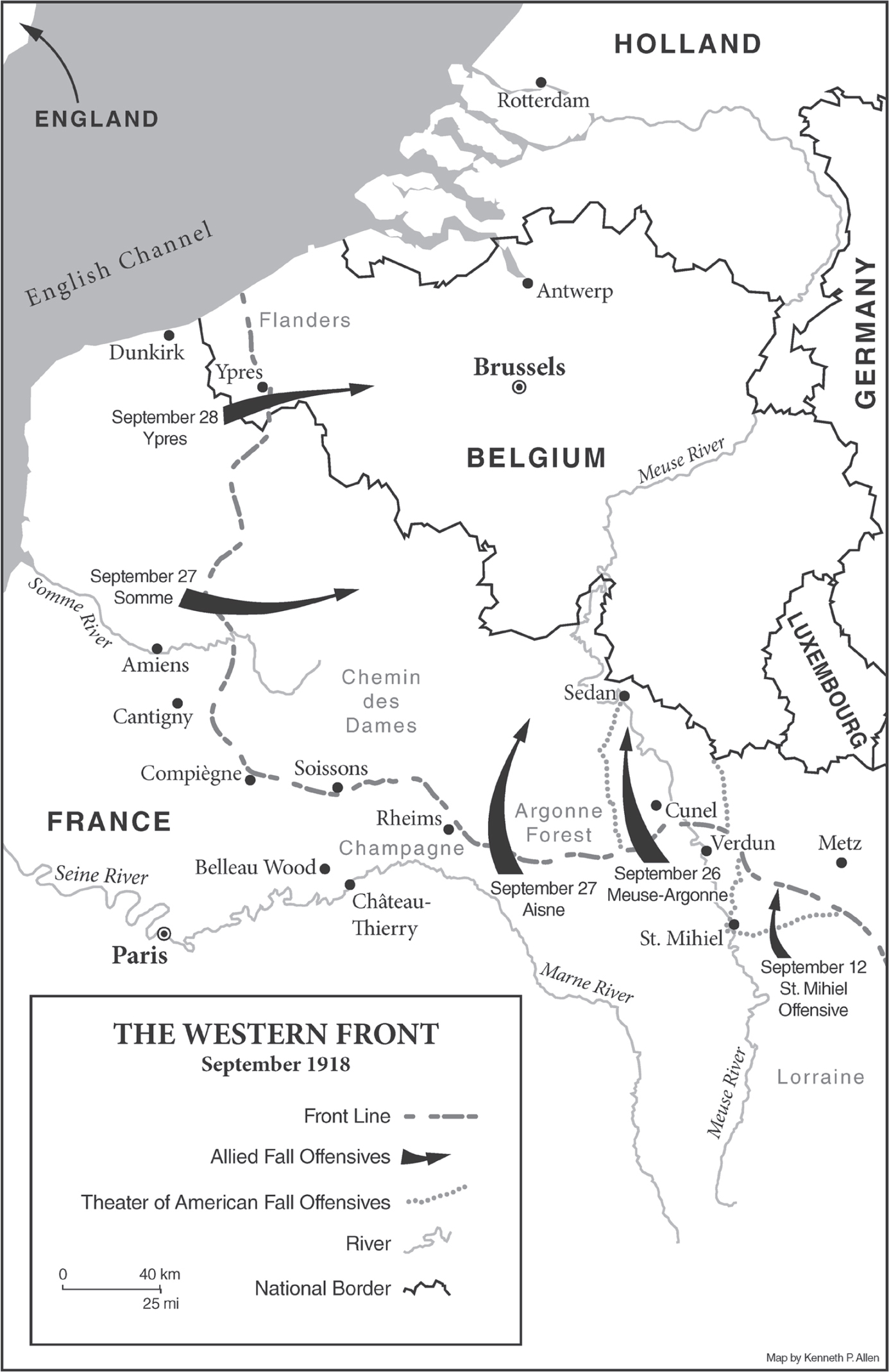

The great Allied offensive of fall 1918 would commence on September 26 and involve armies from many nations attacking the German army along much of the Western Front. The German position was a crescent-shaped bulge, stretching from Flanders in the west to the Vosges Mountains to the east. The Belgian and British armies would push east through Flanders, driving the Germans back into Belgium, while the French would pressure the center of the enemy line in Champagne. Foch ordered the Americans to attack the German left flank along the Meuse River east of the Argonne Forest, aiming for the vital railhead at Sedan. It was a massive undertaking designed to crush the German defenses that ran through northern France.

After the battles of the summer, American units were scattered across northern France, supporting the British and the French. Pershing finally concentrated most of his men on a single front in Lorraine and under a unified command to attack the Germans. He activated the 1st Army on August 10 with himself as its commander and moved headquarters to Neufchâteau to be closer to the front.

Before the fall offensive commenced, Pershing had one major task to accomplish: to pinch off the Saint-Mihiel salient. The Germans had occupied this triangular salient in 1914 and held it against repeated French attacks. The city of Verdun sat in its shadow to the west, and as the Americans drove deeper in the Meuse-Argonne region, the salient would expose them to ever greater flank attacks. Pershing wanted to eliminate the salient while also testing his newly unified army. Saint-Mihiel would become the first American-led battle in France.

Staff officer George Marshall was tasked with developing the plan to reduce the Saint-Mihiel salient. But before the offensive could commence, he was redirected to plan how to move most of the American army up to the front for the pending Meuse-Argonne Offensive. This was a massive coordination effort. The bulk of the army would shift over from Saint-Mihiel, displacing some 200,000 French soldiers who occupied the zone north of Verdun. And to complicate matters, there were only three roads to supply the Meuse-Argonne front. It would take two weeks to reposition the army sixty miles to the northwest in time for the joint allied offensive on September 26. Marshall called it the “hardest nut I had to crack in France,” but one that “represented my best contribution to the war.” His operational planning ensured that more than a half-million American soldiers got into place on time for the expected offensive.40

For the Saint-Mihiel Offensive, Pershing assembled a powerful force of 550,000 American troops and 110,000 French soldiers to attack the German salient. The army borrowed 267 light tanks from the French, and behind the lines were more than 3,000 artillery pieces, mostly British or French-made and partly manned by American gunners. The preparations for Saint-Mihiel were done in the dreary, cold downpour, as the autumnal rains had come, turning the battlefield and trenches into muck.41

For his support at Château-Thierry and the Marne, Billy Mitchell was promoted to chief of air service for the 1st Army. He assembled a force of nearly 1,500 planes to challenge the Germans over Saint-Mihiel. He offered to take Pershing’s staff on an airborne reconnaissance, but he only got one taker. “I could have taken them myself and protected them so that there would have been ninety-nine chances out of a hundred of their getting back unscathed (even if they did get killed, there were plenty of people to step into their shoes),” he wrote, probably with some irony.42

The American attack on the Saint-Mihiel salient began on September 12. In the past, the Allies had used lengthy, days-long bombardments to destroy German defensive positions and barbed wire entanglements in advance of an attack, but often all this did was give the enemy enough time to gather reinforcements for a counterattack. The preliminary bombardment at Saint-Mihiel was only four hours, designed to soften the German position but without giving them time to bring up reinforcements. This was a method that the Germans themselves used with their storm trooper tactics. In addition, the shorter bombardment meant fewer shell holes for the tanks to drive through.

With such a short bombardment, there was no guarantee that the German barbed wire guarding the trenches would be breached. American engineers came up with several solutions to mitigate this: they carried wire cutters to cut lanes and used Bangalore torpedoes to blast holes in the wire. In some places, they constructed contraptions made of chicken wire that they simply lay over the barbed wire, allowing the doughboys to walk over it.

The main attack fell on the south side of the salient. On its west side, a steep ridge confronted Allied forces. Their job was to hold the Germans in place while the main body delivered a right-punch to their rear. The main body of infantry attacked at 6:00 A.M., quickly breached the German lines and swept the enemy back miles. Colonel Douglas MacArthur led a brigade of the 42nd Rainbow Division in the assault. A brigade of French-built light tanks commanded by George Patton supported him; in fact, the two men met on the battlefield. “I joined him and the creeping [German] barrage came along toward us, but it was very thin and not dangerous,” Patton wrote about meeting MacArthur. “I think each one wanted to leave but each hated to say so, so we let it come over us.” The tanks did well, advancing with the infantry until the vehicles ran out of gas.43 The next day, the attacking force linked up with a column that had pushed through the German heights to the west. The Saint-Mihiel salient was now closed just a day after the battle had commenced. Some 16,000 prisoners were captured and 450 guns seized. American casualties were 7,000 men killed or wounded.44

Despite the massed air power, Billy Mitchell was unable to provide much airborne support for the Saint-Mihiel Offensive because of the low cloud ceiling and rainy weather. Eddie Rickenbacker managed to take off with another pilot to scout the battlefield. They flew over the retreating German lines and spotted countless fires: the Germans had torched equipment and supplies that they could not carry. Rickenbacker spotted a horse-drawn German artillery battery stretched out along a road. The two pilots zoomed in at low altitude and sprayed the column with bullets, killing horses and men and throwing the battery into chaos.45

On September 15, a U.S. Army air serviceman named Lee Duncan was scouting for a new airfield in the newly liberated Saint-Mihiel salient. He came to the village of Flirey and there found a demolished kennel. There were no surviving dogs except a female German shepherd who had recently given birth to a litter of five pups. All were on the brink of starving. Duncan took the dogs back to his unit, which quickly adopted the canines and brought them back to health. Duncan gave four of the dogs away but kept a male and female puppy. They were named Rintintin and Nénette, after the good luck charms that French children gave to doughboys. After the war Duncan returned home with his dogs, although Nénette would succumb to pneumonia. Changing the spelling of the male dog’s name, he trained Rin Tin Tin to do tricks, and got the dog into Hollywood movies in 1922. Over the next decade, Rin Tin Tin would wow movie audiences in twenty-seven films and win international fame.46

With the success at Saint-Mihiel, a rich enemy target lay just over horizon: the strategic manufacturing center and German fortress city of Metz. It was only lightly defended. But Ferdinand Foch had his timetable for the fall offensive, and the Americans were expected to attack on the Meuse-Argonne in a matter of days. The Allies missed an opportunity to capture a strategic asset at low cost. Douglas MacArthur wrote later, “I have always thought this was one of the great mistakes of the war.”47

The Saint-Mihiel Offensive turned into a deceptively easy victory for the Americans. They had not faced a resolute enemy, as the Germans had already pulled their best soldiers from the salient. As Pershing prepared the army for the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the Americans would confront a far more determined foe. Their commander still believed his troops could sweep through the German lines and avoid a war of attrition. In this Pershing would be tragically mistaken. The bulk of American forces were still not combat tested. In fact, much of the army was only partly trained.

Meuse-Argonne

Following Colonel Marshall’s logistical plan, Pershing quickly repositioned the American 1st Army from Saint-Mihiel for the Allied fall offensive, scheduled to begin on September 26. His objective was the city of Sedan, a strategic logistical point for the Germans near France’s border with Belgium, as the main railroad line supplying the German army in France passed through the city. The Prussian army had encircled French Emperor Napoleon III at the town in 1870 and forced his surrender and abdication. It was also the town where the Germans broke through the French lines during the blitzkrieg in May 1940 that led to the capitulation of France. If the Americans could capture Sedan in 1918, it would cut off much of the German army from resupply in northern France. But first they would have to fight their way through forty miles of German-held territory.

Some 600,000 doughboys were concentrated along a twenty-four-mile stretch of the front between the Argonne Forest to the west and the Meuse River to the east. Here Pershing would land his main blow, pushing the army to the northwest toward Sedan. He organized three corps on the front lines, each composed of three infantry divisions totaling 225,000 men who would assault the Hindenburg Line on day one. The French 4th Army would attack the Germans just west of the Argonne Forest.

Billy Mitchell was promoted to lead the air service for the army’s 1st Corps under General Hunter Liggett, whom he would support for the duration of the war, commanding larger air groups as Liggett took command of the 1st Army. Liggett was perhaps a surprising choice; he was past sixty years old, nearing retirement, and overweight. “We are too old to make war,” he told Pershing, who was three years younger. “If I were fifteen years younger I should not be sitting here before a map; I should be out on a horse all over the Front.” Perhaps that was true, but he was also an effective and energetic leader, and above all, Pershing had faith in him. Liggett steadily rose from brigade to division to corps to army commander during the war. He proved a skilled tactician who quietly abandoned Pershing’s open warfare doctrine in favor of combined arms operations, a leader who adapted himself and his men to the realities of the modern battlefield.48

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive was the largest military offensive in American history, a tremendous logistical feat as the soldiers and supplies moved up in long night marches. “To call it a battle may be a misnomer, yet it was a battle, the greatest, the most prolonged in American history,” Pershing wrote proudly after the war.* The offensive would last forty-seven days, ended only by the Armistice.49

Facing the American 1st Army were three formidable German defensive belts that comprised the Hindenburg Line. The Germans actually called it the Siegfried Position, and the three lines were named after female characters in composer Richard Wagner’s operas: Giselher, Kriemhilde, and Freya. The German commander in the region, Max von Gallwitz, was an experienced general who initially had just 24,000 men along the front, deceptively deployed six kilometers behind the main line. The Germans were well dug in, though they expected the main American blow to fall at Metz, as it was so close to Saint-Mihiel.50

Shortly before Meuse-Argonne, Eddie Rickenbacker was promoted to commander of the 94th Pursuit Squadron. He was already an ace pilot, but most of his kills were still ahead of him. On his first day of command—September 25—he alone attacked a German squadron of seven aircraft, shooting down a Fokker and a photography plane. For this he would be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1930.

At 2:30 A.M. on September 26, a massive artillery bombardment began of German lines. At the same time, American pilots took to the air in their Spad fighter planes and blew up ten observation balloons, their giant hydrogen-filled gas bags exploding in a rain of incendiary bullets and crashing to the ground. (The Germans sent up new balloons within days.)51 Three hours after the bombardment began, the guns shifted to a rolling barrage as American infantrymen advanced just behind it for the German trenches. The Germans were heavily outnumbered but well entrenched, and the fighting was murderous. The American army advanced slowly through the devastated landscape.

The first day was foggy, which provided some cover for the advancing Americans. The French had supplied light tanks to protect the infantry. Tanks had proved useful as mobile gun platforms during operations. However, German artillery easily knocked out the tanks. On the opening day of Meuse-Argonne, Lieutenant Colonel George Patton, who commanded a brigade of light tanks, advanced several miles into the German position in heavy fog. He was pinned down by machine-gun fire. When he attempted to charge the position on foot, a bullet struck him in the thigh. The war was over for the man who would become a legendary tank commander in World War II.52

The key to the first German line was Montfaucon, a lofty, 1,122-foot-tall citadel where the German crown prince had led the campaign against Verdun in 1916. The French dubbed it “Little Gibraltar.” The rookie 79th Division assaulted the fortress frontally. They got no help from General Robert Bullard’s III Corps to the east, which had advanced eight miles on the first day and could have swung around behind the fortress to capture it, preventing a bloodbath. Instead, German machine guns inflicted heavy casualties on the massed doughboys. The 79th finally captured Montfaucon after two days of fighting that cost the division 3,500 casualties.53

Pershing had achieved strategic surprise over the thinly held German line, but he entertained unrealistic expectations for the offensive: the objective on day one was to reach Cunel and Romagne at the center of the Kriemhilde Line (the second of the German defensive belts), nine miles north of the American jumping-off point. Instead, it would take the Americans nearly three weeks to get there, fighting the entire way. By the second day of the offensive, the 1st Army had penetrated part of the first German line, but the Americans were still far short of Pershing’s objectives. General von Gallwitz brought up reinforcements and the fighting intensified. The Germans were well trained and dug in, and the terrain heavily favored their defense. The Germans concentrated much of their best aircraft and pilots to challenge Billy Mitchell’s fighters for command of the skies, and the airborne fighting was fierce. Casualties among pilots were high on both sides.

Pershing’s doctrine of open warfare would prove a costly failure. The frontline divisions were a mixture of veteran and virtually untrained units, the latter of whom rose up in waves to assault machine gun positions and were mowed down, rather than pinning the enemy down with suppressive fire while other troops worked around the machine gunner’s flanks to take him out. As the doughboys moved forward, the artillery struggled to keep up. Poor coordination existed between artillery and infantry in many divisions, resulting in infantry making unsupported attacks with heavy losses and coming under withering German artillery fire.

The autumnal skies opened with cold rain. What passed for roads were a muddy mess, especially after four years of artillery bombardment that had devastated the landscape. Enormous traffic jams clogged the only three roads to the Meuse-Argonne as the Americans brought up immense quantities of munitions and supplies. The logistics of resupplying such a large field army broke down in the mud. Pershing had not allocated military police to direct traffic, nor engineers to continuously repair the roads. It made for a stupendous mess, such that soldiers on the front line were not always fed.

After a week of fighting that had captured the first German “Giselher” defensive line, Pershing ordered a pause to reorganize his exhausted army. The Meuse-Argonne Offensive had stalled and the casualties were high. Some of the infantry divisions needed to come off the line already, as they were disorganized and spent. This was the first combat experience for most of the soldiers, and many of the divisions lost their effectiveness after just a couple days in battle. Veteran divisions replaced the raw frontline troops, such as the 1st Division, which took the position of the disorganized 35th. Pershing renewed the attack on October 4.

Most of the initial offensive took place on the plain east of the Argonne Forest, which represented the American 1st Army’s western boundary. Combat was challenging in such heavily wooded terrain, and so Pershing decided to avoid the forest until the army outflanked it. The Germans took advantage of the woods, hiding artillery batteries and machine guns that fired upon the Americans advancing to the east. German artillery fired from the heights above the east bank of the Meuse River, catching the Americans in a crossfire.

Only one division, the 77th (known as the “Liberty” Division because it was largely made up of New Yorkers), was assigned to pin down the Germans in the Argonne Forest. As the division advanced into the woods on October 2, one battalion of 550 soldiers under Major Charles Whittlesey advanced ahead of its regiment and was cut off and surrounded. German machine gunners pinned down the Americans for five days and prevented relief forces from rescuing the battalion, while both American and German artillery pummeled the doughboys’ position. Whittlesey refused to surrender, despite running out of food and water. The story of the “lost battalion” became one of the most dramatic of the war and spurred much press coverage.54

By this point, the Americans had gained a solid foothold east of the Argonne Forest and could outflank the German position in the woods. The 1st Corps commander, Hunter Liggett, ordered the 82nd Division to assault the forest obliquely from the east, threatening to cut off the enemy line of retreat, while the 77th Division advanced from the south. The plan worked and the Germans abandoned the forest. The Lost Battalion was soon rescued. More than half of the men had been killed or wounded. Whittlesey was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. The Germans retreated to a formidable position at Grandpré.55

On October 7, the same day that the Lost Battalion was rescued, Private First Class John Barkley was in a forward observation post near Cunel when a German battalion launched a counterattack against the 3rd Division. He took shelter in a nearby disabled French tank and rounded up an abandoned German machine gun and 4,000 rounds of ammunition. From this sheltered position, he mowed down hundreds of German soldiers and blunted two counterattacks. For this achievement he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. That same day, two American divisions attacked east of the Meuse River to drive off the artillery that was firing into the flanks of the advancing 1st Army. The attack was also intended to pin down more Germans so they could not reinforce their defensive lines protecting Sedan. The attack quickly bogged down and made little headway.56

One of the more astonishing incidents of the war occurred on October 8 as the Americans were cleaning the Germans out of the Argonne Forest. When his unit became pinned down, a corporal from Tennessee named Alvin York infiltrated his seven-man squad into enemy lines, killed at least twenty-five Germans, destroyed thirty-five machine guns nests, and captured 132 prisoners. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, and later the Congressional Medal of Honor for the feat. It was particularly remarkable given that York had initially registered for the draft as a conscientious objector before a friend convinced him of the rightness of the American cause. York’s story was published in the Saturday Evening Post in 1919, making him a national hero.57

To the west of the Argonne Forest, the French 4th Army was slowly pushing back the Germans. It had notable American reinforcements, including the 369th Infantry—the Harlem Hellfighters—and the experienced 2nd Division, now under General John Lejeune. The Second captured a key German stronghold in early October, the Blanc Mont ridge, helping drive the Germans out of the Champagne region.

East of the Meuse River, the Germans prepared a counterattack on October 9. Airborne reconnaissance spotted the enemy concentration of forces, and Billy Mitchell ordered a major air attack. The French sent 322 airplanes, wave after wave of bombers that pounded the German position while American fighters held off pursuit aircraft. “Just think what it will be in the future when we attack with one, two or three thousand airplanes at one time; the effect will be decisive,” he mused, foretelling the carpet bombing of World War II and Vietnam.58 Mitchell would go on to suggest to Pershing that they assign the 1st Division to the Air Service, equip each man with a parachute, load them on bombers, and drop them into the rear of German lines to attack the enemy from behind. His 1918 suggestion foreshadowed the airborne infantry of the next war.59

Despite the October rain and supply difficulties, American forces were slowly driving the Germans back. George Marshall wrote, “The transportation of ammunition and supplies was rendered difficult over the water-soaked ground; the long cold nights were depressing to the troops, who were seldom dry and constantly under fire, and the normally leaden skies of the few daylight hours offered little to cheer the spirits of the men.” Being a soldier was miserable, as the doughboys were constantly wet and cold.60

Soldiers in France had their letters censored. They were instructed not to give away American military plans, nor reveal casualties or the conditions on the battlefield. Doughboys generally wrote glowing words to their families, probably in the hope that they would not worry. The public had no idea how terrible the conditions were in the trenches, nor what it was like to endure an artillery bombardment to the point of broken nerves, nor what it was like to witness an infantry company get ripped apart by an enemy machine gun, nor what it was like to watch a man choke to death from poison gas, nor what it was like to see a man have half his face shot off by a sniper.

While the fighting raged in the Meuse-Argonne, deadly influenza indiscriminately ravaged the armies. Pershing noted 16,000 cases the first week of October, and eventually 70,000 soldiers would be stricken—and a third of them would die from it. More American troops were killed by influenza than by German bullets. Even Pershing caught the flu, though he stayed on duty and continued leading the army from his train, parked in a wooded siding near Souilly.61

By the second week in October, Pershing was exhausted, as was every man in the army. At one point the commander broke down in tears. He had such high hopes for breaking through the German lines quickly, when in fact the brutal fighting was inflicting devastating casualties. Pershing had not been able to fight the open warfare campaign he hoped for. Instead, the advance was a slog, and the army was losing over five hundred men a day as the Germans tenaciously held on.

Pershing ordered a halt to offensive operations while he regrouped the army and the soldiers rested. On October 12, he announced a reorganization, splitting the American Expeditionary Forces into two armies: the 1st Army west of the Meuse River under General Hunter Liggett, and the 2nd Army east of the river under General Robert Bullard. The 1st Army would continue bearing the brunt of the fighting while the 2nd would pin the Germans in place. Pershing would leave command of day-to-day operations to his army commanders, though in truth he was preoccupied with Liggett’s 1st Army. That same day, Lieutenant Samuel Woodfill advanced ahead of his infantry company near Cunel and took out a series of German machine guns with just his rifle and pistol. He was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

After a two-day rest, Liggett renewed the attack on October 14. The second German line, known as the Kriemhilde Position, occupied the dominant Romagne ridge, blocking the American advance. On the opening day of the attack, the 32nd Division seized the Côte Dame Marie, the Germans’ strongest point on the line. To the east, the 42nd Rainbow Division prepared to assault another strongpoint, the Côte de Châtillon. The V Corps commander, Major General Charles Summerall, told Douglas MacArthur, “Give me Châtillon, or a list of five thousand casualties.”

MacArthur, who led an infantry brigade, responded, “All right, General, we’ll take it, or my name will head the list.” MacArthur split his brigade into two flanking movements to surround the hill, then steadily, platoon by platoon, climbed upward and knocked out the German positions. In two days, MacArthur’s brigade finally secured the strategic hilltop. The cost in human lives was high: one battalion of 1,475 men was down to just 306 men by the end of the battle. MacArthur was cited for bravery once again. He emerged from the Great War as the most decorated American soldier with the Distinguished Service Medal, seven Silver Stars, two Purple Hearts, and numerous decorations from Allied countries.62

The second German defensive line, known as the Kriemhilde Position, was now breached, three weeks after Pershing hoped to capture it. Only one final entrenched line stood in the way, the Freya Position, before the Americans could break out into the open countryside and capture Sedan. The largely green American army was gaining experience and ground against the battle-tested Germans.

Peace Negotiations and the 1918 Election

President Woodrow Wilson had spelled out America’s wartime goals with the Fourteen Points in January 1918. As the year progressed, he added eleven points through diplomatic notes and speeches so that by the end of the war there were twenty-five American conditions for peace. This included a February 11 address that asserted the right of peoples for self-determination. Another speech came on July 4, where Wilson spoke at Mount Vernon. After a rather academic and lawyerly recitation, Wilson reduced the four new points to language that people could understand. “What we seek is the reign of law, based upon the consent of the governed and sustained by the organized opinion of mankind.” If the Central Powers wanted peace, they would have to shed their ruling monarchies and adopt democratic governments. This impactful phrase would provide the foundation for Wilsonian diplomacy and American advocacy for democracy abroad.63

Wilson spelled out the last of America’s war aims on September 27, the day after the Meuse-Argonne Offensive commenced, in a public address at New York’s Metropolitan Opera. These were aimed in particular at the military junta that had commandeered the Central Powers at the cost of civilian government. He knew the war would end at some point—sooner in fact than anyone could imagine—and he set the stage for “a secure and lasting peace,” one founded on the League of Nations, an idea that would be baked into the peace treaty. He wanted to build a peace based on “the principle that the interest of the weakest is as sacred as the interest of the strongest.” It was one of Wilson’s most principled statements, and he expected the league’s covenant to be negotiated in the open and without resorting to “alliances or special covenants.”64

The opera house speech sent a strong signal to the Germans. By October, it was clear that the German army was in trouble. It was being pushed back on all fronts. Key allies like Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire had sued for peace, opening Austria’s southern flank to Allied invasion. Austria-Hungary soon made peace overtures. The German Supreme Army Command signaled that the army faced collapse, and the government of Georg von Hertling resigned. Hindenburg wrote a memo to the government that concluded: “In these circumstances the only right course is to give up the fight, in order to spare useless sacrifices for the German people and their allies. Every day wasted costs the lives of thousands of brave German soldiers.” On October 3, Prince Maximilian of Baden formed a new government and was appointed imperial chancellor. He had publicly called for peace and had opposed unrestricted submarine warfare, and his installation as chancellor was a stepping-stone toward an armistice. Maximilian would only serve as chancellor for five weeks, but his term in government would bring a close to the war.65

On October 6, Maximilian sent a note to President Wilson asking to begin peace negotiations based on the Fourteen Points and Wilson’s subsequent addresses (a total of twenty-five points). A series of diplomatic cables, routed through the Swiss government, followed between the two men. The Germans tried to save their army by appealing directly to the United States, rather than to the Allies, but Wilson deflected that by responding that an armistice was a military matter best decided by the generals—in this case, Marshal Ferdinand Foch.

The question of peaceful terms for the Germans was a contentious debate in late 1918. Famed defense attorney Clarence Darrow came down with the hardliners in the war: “Peace will come when the German military machine is destroyed, and it cannot come before,” he wrote in an article.66 Henry Cabot Lodge, the leading Republican in the Senate, made a speech in late August 1918 demanding German unconditional surrender. “No peace that satisfies Germany in any degree can ever satisfy us. It cannot be a negotiated peace. It must be a dictated peace, and we and our Allies must dictate it.”67 Theodore Roosevelt likewise called for a “peace based on the unconditional surrender of Germany.” Both Lodge and Roosevelt stood squarely against a peace negotiated on the Fourteen Points.68

Word soon leaked that the Germans were asking for peace, and that Wilson might go soft on them. As the German army retreated, the American press, GOP leaders, and Theodore Roosevelt called for Germany to surrender unconditionally, casting off Wilson’s more moderate terms. On October 13, TR denounced Wilson for his efforts for a negotiated peace. “I must earnestly hope that the Senate of the United States and all other persons competent to speak for the American people will emphatically repudiate the so-called fourteen points,” which would let Germany too easily off the hook.69

Wilson had made it clear that, if the monarchy or the military continued to rule Germany, then the country’s only option would be to surrender, rather than negotiate. The message was received: the Kaiser would have to abdicate. When the civilian German government confirmed that it was in fact speaking for its people, and not for the military, another eruption broke out in Congress: senators wondered why Wilson was not consulting with them. On October 14, Senator Henry Ashurst of Arizona paid an unscheduled visit to the White House to meet with Wilson. The senator was highly agitated and denounced any armistice before Germany was totally defeated. “If your reply should fail to come up to the American spirit, you are destroyed,” Ashurst warned.

Wilson took umbrage. “So far as my being destroyed is concerned, I am willing if I can serve the country to go into a cellar and read poetry the remainder of my life,” he intoned. He reiterated what he had said all along: the United States would make peace on the basis of the Fourteen Points, rather than demanding unconditional surrender.70

Josephus Daniels recorded Wilson’s exchange with Senator Ashurst in his diary. Wilson told Ashurst, “Why don’t you Senators sometimes give me credit with not being a damned fool?” He explained it in terms that the cowboy senator could understand: “If you and I were in a fight and you held up your hands and asked for quit and would agree to all I said, and then I made you disarm, wouldn’t that be all right?” Ashurst said that would be fine. Wilson then asked if the senator would prefer the Bolsheviks over the Kaiser—a distinct possibility if the German authorities were overthrown after surrendering unconditionally.71

Wilson meanwhile continued exchanging diplomatic notes with the Germans. Encouraged by their positive response to his peace overture, Wilson dispatched Edward House to Europe to lay the groundwork. He had immense confidence in his political adviser, remarking, “I have not given you any instructions because I feel you will know what to do.”72

Republicans were speaking out against Wilson’s goal to bring an early end to the war. The president responded with a statement of his own that would have profound political repercussions. On October 19, Wilson appealed publicly for a Democratic majority in Congress, two weeks before the midterm election. “If you have approved of my leadership and wish me to continue to be your unembarrassed spokesman in affairs at home and abroad, I earnestly beg that you will express yourselves unmistakably to that effect by returning a Democratic majority to both the Senate and the House of Representatives.” His reasoning was that the Republicans were undermining his wartime leadership: “they have sought to take the choice of policy and the conduct out of my hands and put it under the control of instrumentalities of their own choosing.” Wilson, who only five months earlier had declared, “politics is adjourned,” now demanded that Democrats control the levers of power.73

Rather than champion national unity as a wartime president, Wilson called for a partisan Congress, one made up of Democrats, to ensure he could get his agenda through. That did not sit well with many voters. There was strong dissatisfaction against the president for the way he had run the war, all but ignoring domestic affairs. Wheat farmers, who had earned a federally guaranteed price, were upset that Wilson had rejected a twenty percent rise in the price floor in a time of high inflation. The pro-Republican business community had a long-standing grudge against Wilson for reducing protectionist tariffs while raising income taxes and war profit taxes. Newspaper editors chafed at self-censorship and the government’s monopoly as a news source about the war effort. And, frankly, many Americans sided with the Republicans and wanted Germany to surrender unconditionally.74

Wilson had consulted with his political adviser, Edward House, about the speech, but House said nothing, though he sensed it would lead to trouble. House was on a ship bound for France when Wilson gave the speech. A week later, he wrote in his diary that it was “a political error to appeal for a partisan Congress. If he had asked the voters to support members of Congress and the Senate who had supported the American war aims, regardless of party, he would be in a safe position.” House regretted that he did not tell Wilson that the partisan speech was a bad idea.75

Wilson understood the firestorm that he stoked, and he knew that the talk of an armistice would affect the election. Josephus Daniels penned in his diary that Wilson “might find popular opinion so much against him he might have to go into cyclone cellar for 48 hours.” But Wilson also hoped the public understood that no one would benefit from having to fight all the way to Berlin.76

Wilson’s appeal for a Democratic Congress backfired. The midterm election on November 5—six days before the Armistice—witnessed sizable Republican gains in Congress, and the GOP now controlled both houses. The 1918 election, as it turned out, marked the death knell of the Progressive Era, but no one knew that yet. The last progressive still occupied the White House, for now.

The midterm election of 1918 was a mess of Wilson’s own making. The Espionage and Sedition Acts effectively silenced the opposition to the war—especially from pacifists on the left such as Eugene Debs. Wilson had muzzled a key part of his political base, a fact that helped him lose control of Congress as a consequence.

With the Republican capture of the Senate—commencing in March 1919 when the new Senate met—Henry Cabot Lodge would become the majority leader and the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Republicans now had a narrow command of the Senate with forty-nine seats to forty-seven Democrats. Lodge was Wilson’s staunchest opponent in the Senate, and he believed the Republican capture of Congress was a sign that the country wanted a dictated peace on Germany, not a peace of compromise.77

The Final Fighting

General Pershing sent a message to the American army on October 17, reminding the soldiers not to let up on the Germans, who were clearly in dire straits: “Now that Germany and the Central Powers are losing, they are begging for an armistice. Their request is an acknowledgement of weakness and clearly means that the Allies are winning the war. That is the best of reasons for pushing the war more vigorously at this moment.” Pershing ended, “There can be no conclusion to this war until Germany is brought to her knees.”78

The Allied Supreme War Council met in late October in to consider what terms should be part of the armistice. Pershing’s views were the most strident of the council’s: “Germany’s morale is undoubtedly low, her Allies have deserted her one by one and she can no longer hope to win. Therefore we should take full advantage of the situation and continue the offensive until we compel unconditional surrender.” His views were more in line with the Republicans, who wanted the same thing, not Wilson’s peace without victory.79

Yet Marshal Ferdinand Foch believed that if France could achieve its military goals without further bloodshed, then why not grant the Germans an armistice? The cease-fire itself would effectively be a German capitulation, even if the words “unconditional surrender” were never written. Having reached Paris on October 26 and apprised himself with the situation, Edward House realized that the war might actually end sooner than anyone expected. He cabled the president on October 28th: “Things are moving so fast that the question of a place for the Peace Conference is on us.”80

Germany’s main ally, Austria-Hungary, was squeezed on two sides: a multinational Allied force moved up the Balkans to attack it from the southeast, while Italy opened an offensive that broke through the demoralized Austrian lines. Austria-Hungary’s Emperor Karl I realized that his country was defeated, and the Austrians were granted an armistice on November 3. Germany now fought alone, all of its allies having deserted it.

After taking command of the 1st Army, General Hunter Liggett directed special attention to fixing his army’s logistics and supply lines. The army was now better led, its logistical nightmare having largely been solved, and Liggett planned an operation to break through the final German Freya line. He abandoned Pershing’s overreliance on infantry and instead concentrated heavy artillery and planned attacks with limited, attainable objectives that would allow artillery and supplies to keep up with the advancing infantry. It was this final assault that showed that the American army had reached fighting parity with the Allies and the Germans. Yet even at this late stage in the war, the army relied entirely on Allied armaments and munitions. “It is interesting to note that during the entire operation [Meuse-Argonne] the First Army did not fire one American gun, except the 14-inch naval guns, nor did it use one American shell manufactured for American use,” Liggett noted after the war.81

The Americans in the Meuse-Argonne assaulted the last remaining German defensive line on November 1. As usual there was a short, sharp artillery bombardment, then an infantry attack at 5:30 A.M. Within hours the doughboys broke through the German position, and the troops advanced northward quickly toward Sedan through open countryside. Progress was now measured in miles, rather than yards. Part of the 2nd Division made a stealthy four-mile night march through enemy lines, sweeping up many prisoners who were fast asleep.82 Another American force made a surprise crossing over the Meuse River on November 5, a move to outflank the German defenders on the eastern heights of the Meuse opposing the Second Army. Humorist Will Rogers joked, “The Kaiser was on the verge at one time of visiting the western front then he said, ‘No I will just wait a few days till it comes to me.’”83

Revolution broke out in Germany. It began with a mutiny in the High Seas Fleet when sailors cooped up in port with bad rations for four years rebelled. Communist revolutionaries, inspired by the Russian Revolution and Bolshevik coup, plotted to overthrow the German government and staged an uprising in Berlin on November 9. On that day Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated and went into exile in Holland.

In his July 4 speech declaring that Germany could not be ruled by an autocratic government, President Wilson effectively demanded that the Kaiser abdicate before peace negotiations could begin. It meant toppling the German aristocracy at a time when the Bolshevik threat was real. Nevertheless, the Kaiser abdicated, while Prince Maximilian stepped down from the German chancellorship after just a brief but vital month. A government formed under Social Democrat Friedrich Ebert once the Kaiser abdicated, handing over the reins of the government to civilians as Wilson required. (Ebert would be elected Germany’s first president two months later.) The military cautiously threw its support behind Ebert with the condition that he fight Bolshevism. General Ludendorff resigned and fled to Sweden.

On November 7, German delegates entered French lines to request an armistice, and met with Ferdinand Foch in his railcar parked in Compiègne Forest. The United Press falsely reported that day that the Germans had signed an armistice. GERMANY SURRENDERS; THE WAR IS OVER read headlines of afternoon newspapers. Jubilant crowds gathered at the White House to celebrate. Around the country, judges closed courts, schools ended early, churches rang bells, and thousands of people took to the streets, vacating their jobs and offices, some taking to drinking in celebration. A large crowd gathered at the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia. Even the New York Stock Exchange closed early. Shortly after noon, Secretary of State Lansing issued a statement denying that there was a cease-fire. In New York, the mood turned sour when newspapers reported that the armistice rumor was false. The police stepped up their vigilance and saloons closed early, lest angry, drunken crowds protest.84

Foch provided the terms of the cease-fire to the German delegation. The delegates crossed the front line to confer with their country’s leaders, then returned to Compiègne to announce that Germany would accept the terms. The Armistice was signed at 5:15 A.M. on November 11, and a cease-fire would commence in six hours. There was a poetic timing to the Armistice: The guns would fall silent for the first time in more than four years on November 11, specifically the eleventh minute of the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

On the eve before the Armistice was declared, American forces converged on Sedan, reaching the heights above the vital town shortly before the Armistice. A near tragedy was averted: General Charles Summerall was determined that the 1st Division should capture the town, and he sent the division in front of the 42nd Division at night, a maneuver that could have led to fratricide. American troops under Douglas MacArthur intervened before the two divisions started shooting at each other. (During the nighttime march 1st Division soldiers briefly arrested him.) George Marshall called it a “grandstand finish,” but Hunter Liggett was furious that his commanders were willing to risk their men’s lives just for bragging rights.85

Under the terms of the Armistice, the Germans were required to withdraw immediately from Belgium and France and completely across the Rhine River, including returning Alsace-Lorraine to France. The Allies would militarily occupy the west bank of the Rhine and demanded that the Germans hand over much of their railroad rolling stock. Germany would disband most of its army and surrender the High Seas Fleet, which would be interned in Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands off Scotland and wait there until the Allies decided how to distribute the ships among the victors. The intention of the Armistice was not to disarm Germany completely—the Allies understood the threat posed by the Bolsheviks—but to reduce Germany’s offensive capabilities. Should the Allies need to invade if the Armistice collapsed, they wanted the German army weakened such that it could offer little resistance.

Captain Harry Truman wrote his fiancée Bess Wallace the morning of the Armistice as artillery bombarded German lines, trying to use up all of their ammunition before the cease-fire began. “I knew that Germany could not stand the gaff. For all thier [sic] preparedness and swashbuckling talk they cannot stand adversity,” he wrote. “France was whipped for four years and never gave up and one good licking suffices for Germany.”86

Colonel George Marshall had gone to bed at 2:00 A.M. on November 11 at army headquarters, but he was soon woken to deal with orders for four divisions, which were to begin a march northward that morning. He canceled their march from his bed and went back to sleep, not getting up until 10:00 A.M., an hour before the Armistice began. The officers gathered for a late breakfast when a huge explosion knocked them out of their chairs. Fortunately no one was hurt. A pilot soon ran in to survey the damage; he had just landed on an adjacent field from a bombing run when his final bomb fell out of the rack near the officer’s quarters on his landing approach.87

General John Lejeune, who led the battle-hardened 2nd Division, had thrown his division across the Meuse River shortly before the Armistice while the two sides lobbed artillery shells at one another. “A few minutes before eleven o’clock, there were tremendous bursts of fire from the two antagonists and then—suddenly—there was complete silence,” he wrote. “It was the most impressive celebration of the Armistice that could possibly have taken place.” That night the cold, soaked doughboys and marines lit campfires and set off fireworks while automobiles and trucks turned on their lights. Lejeune heard many a cheering soldier shout, “It looks like Broadway.”88