Introduction

In her study of the transition from slavery to free labor in nineteenth-century Maryland, Barbara Fields refers to freedom as a “moving target” that was constantly being redefined in contests over economic and political rights that freedpeople attempted to assert and planters sought to deny.1 At that time, the meaning of freedom for the nation’s working class was being transformed as the rise of industrial capitalism pushed the status of self-reliant property owner out of reach for large numbers of wage earners. Historically, Americans had considered property ownership essential to the enjoyment of liberty and the basis of citizenship in a democratic republic, but when freedpeople and their allies suggested that real freedom required a redistribution of land and resources in the South to ensure economic independence for former slaves, political leaders balked. They believed the future lay in large-scale agriculture, not small farms. If freedpeople and poor white southerners received land that allowed them to live and work on their own terms, who would be left to labor on the plantations, and what would stop propertyless northerners from demanding similar reforms?

By the late nineteenth century, the debate was settled in favor of a more restricted definition of freedom that granted legal and political rights to freedpeople but left most of them dependent on white landowners for employment. Former slaves were not to become independent small farmers but instead joined white workers as free laborers, selling themselves in the marketplace for the best price they could find. Even those limited gains disappeared after white supremacists regained control of the state governments in the South and the federal government withdrew its presence from the region, leaving black people unprotected against the onslaught of disfranchisement and segregation legislation passed in the 1880s and 1890s. The Jim Crow laws served to limit workers’ bargaining power and maintain an ample supply of labor for plantation owners by denying black people access to education, economic opportunities, and the legal system. Most African Americans ended up as sharecroppers, working land owned by white people in return for a portion of the proceeds from the crops they grew each year. Paid only once annually, sharecropping families relied on plantation owners to supply housing, food, clothing, and other necessities throughout the year, the costs of which were deducted from their pay at harvest time.2

Until the 1930s, black labor was so cheap in the South that planters had little incentive to mechanize their operations. That began to change during the Great Depression, when the federal government moved to limit production and raise farmers’ incomes by paying them to take land out of cultivation. Plantation owners were supposed to retain tenants and sharecroppers on their farms and share the subsidy payments they received from the government with their workers, but loopholes in the legislation enabled many landlords to evade this responsibility. Thousands of families lost their homes and livelihoods when landowners reduced the number of workers they employed and invested their government checks in tractors and other labor-saving technology instead. Agricultural mechanization accelerated during World War II as many black laborers left to work in defense industries, which reduced the supply of workers and raised labor costs, and it received a final push with the rise of the civil rights movement and the threat of black political empowerment in the 1950s and 1960s. In those decades, economic and political considerations drove plantation owners to get rid of their remaining laborers as quickly as possible, leading to mass evictions that displaced hundreds of thousands more people.3

The civil rights legislation passed in the mid-1960s freed African Americans from the oppressions of the Jim Crow system during another period of capitalist transformation that threw long-standing assumptions regarding the meaning of citizenship into disarray. Just when white workers had managed to secure a new version of the republican ideal rooted in unionized manufacturing jobs with generous pay and benefits, New Deal social welfare programs that offered a modicum of economic security, and federally subsidized home ownership, the ground shifted again as the nation made the transition to a postindustrial, globalized economy that rendered a good proportion of the labor force obsolete. The black plantation workers who were pushed off the land by the modernization of southern agriculture were not to join the industrial working class in the post–civil rights era. Instead, they were the first to experience the transition from free labor to displaced persons that awaited millions of other workers in this new era of economic restructuring.

Rural black southerners found that equal rights were easier to establish on paper than in practice in communities where their labor was expendable and white racists controlled access to the means of economic survival, including employment, credit, housing, and public assistance. African Americans who ventured to register to vote or participate in elections risked being fired from their jobs, evicted from their homes, denied loans, or cut from welfare rolls. Thousands of others faced unemployment and homelessness as the southern sharecropping system headed into its final death spiral. Black people’s economic dependence severely limited their political independence, and civil rights leaders understood that raising black southerners’ economic status was a prerequisite to ensuring the other rights they had fought for in the 1960s. For many people, simply obtaining such basic necessities as food and shelter was a more immediate concern than was voting. As Alabama activist Ezra Cunningham explained, “You can’t eat freedom. And a ballot is not to be confused with a dollar bill.”4

Cunningham’s insight reflected his and others’ long involvement in a struggle for social justice that predated the civil rights movement and continued beyond it. A farm owner and schoolteacher in Monroe County, he quit his teaching job when the superintendent asked him to take the children out of class to pick cotton. He taught farming techniques to black soldiers returning from the war in the 1940s and encouraged African Americans to register to vote in the 1950s. When national civil rights groups came into Alabama at the height of the freedom movement, Cunningham was among the hundreds of local people who participated in demonstrations and voter registration drives that successfully pressured the federal government into outlawing racial discrimination. Activists’ struggles did not end there, however. In the decades following passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts, Cunningham and other movement veterans worked to draw attention to persistent forms of racial oppression that required more action. Their goals extended beyond desegregation and political participation to encompass measures designed to ensure economic security, including jobs with adequate incomes, affordable housing, and access to medical care. Civil rights and social justice activism merged in various initiatives aimed at asserting economic rights that were needed to solidify the legal and political rights won in the mid-1960s.5

Activists’ battles for both ballots and dollars faced steep challenges. The economic revolution wrought by mechanization threatened to negate the political revolution brought about by the civil rights movement. In plantation counties where hundreds of sharecropping families were once employed cultivating the cotton and other cash crops that enriched their landlords, human beings gradually disappeared from the fields as tractors, herbicides, and mechanical harvesters took over their jobs. Farm employment in the South declined from 5.6 million to 3.1 million between 1940 and 1960, and another 1.2 million positions were gone by 1969.6 With these changes came a fundamental shift in the relationship between white and black people. For most of the region’s history, the central concern of white landowners was how to force black people to work for them, a problem they solved by restricting economic opportunities and political rights for African Americans in the slavery and Jim Crow eras. In the 1960s, the focus shifted to deciding what to do with workers whose labor was no longer needed—and who could now vote. Just when black southerners seemed poised to take their place as equal citizens in their communities, many of their white neighbors wondered whether there was a place for African Americans at all.

As the new economic order took shape, planters and political leaders argued that the best solution to unemployment was for displaced workers to leave the region and seek work elsewhere. In response, African Americans asserted that they had a right to stay in the communities where they had lived and worked for generations. Both sides understood the political implications of black out-migration from counties where African Americans made up significant voting majorities. As Mississippi activist Lawrence Guyot observed in February 1966, “even if Negroes get registered, we still have to worry about keeping them here.” For their part, white leaders viewed out-migration as a way to dilute black political power and avoid the considerable expenditures needed to address the unemployment problem. Robert Patterson, a segregationist who founded the Citizens’ Council in 1954 to oppose the civil rights movement, called black Mississippians an “economic and political liability” and stated, “The only thing for the Negro to do is to voluntarily migrate.”7

This book examines the ideological debates and political struggles that occurred in the cotton plantation regions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana as residents wrestled with the dilemmas posed by agricultural displacement and black political empowerment after the mid-1960s. I use the terms “displacement” and “displaced worker” in the same way they were used by contemporary observers in the mid-twentieth century: to refer to people employed in agriculture (farm owners, tenants, sharecroppers, and day laborers) who lost their jobs when their labor was no longer needed. Most of these people would also meet the technical definition developed by the Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics in the mid-1980s (when displacement affected large numbers of industrial workers nationwide) and still in use today: “persons 20 years and over who lost or left jobs because their plant or company closed or moved, there was insufficient work for them to do, or their position or shift was abolished.”8

Economic restructuring and the passage of civil rights legislation necessitated a renegotiation of social relationships and generated sharp contests over the distribution of power and resources in southern plantation regions. When some activists called for government action to address mass unemployment and poverty, opponents argued that these problems resulted from the normal workings of a free market economy and required no intervention. Casting displacement as a natural phenomenon that was beyond human control absolved planters from responsibility for the crisis, denied any need for redistributive economic policies, and preserved the disparities in wealth produced by generations of exploiting black people’s labor. Fierce defenses of free enterprise and limited government replaced Jim Crow laws as a key means of maintaining regional elites’ political and economic power. These ideas also informed responses to mass layoffs and labor displacement that occurred on a national scale as the United States made the transition from industrial capitalism to finance capitalism in the late twentieth century. Understanding what happened to black workers in the plantation South therefore helps us make sense of developments that shaped other Americans’ experiences in the post–civil rights era.

The three Deep South states examined in this book were notorious for the mistreatment their white residents inflicted on African Americans in the slavery and Jim Crow eras, and they emerged as centers of black political activism in the 1960s. The fertile lands located along floodplains in northern Louisiana and western Mississippi and stretching east through the Alabama Black Belt were home to some of the richest white people and the poorest black people in the nation. As both white and black residents understood, these two facts were connected, for the vast fortunes that planters accumulated rested on denying black laborers a fair share of the wealth they produced. White supremacists in the plantation counties frequently led the way in devising mechanisms for disempowering African Americans that were later adopted throughout the South. In the 1960s, well-publicized events such as the desegregation and voter registration efforts of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in Louisiana, Freedom Summer in Mississippi, and the Selma to Montgomery march in Alabama placed local activists in these states at the forefront of the black freedom movement.9 Clashes between supporters and opponents of racial equality in this region helped shape other Americans’ understanding of the civil rights struggle and its aftermath. The media spotlight and close attention from federal policy makers gave participants on both sides powerful forums for disseminating their contrasting views. Events in these plantation counties strongly influenced national perceptions and responses, making them a logical focus for this study.10

This book is informed by, contributes to, and connects several historiographical strains that have emerged in the past two decades. Whereas many accounts of the struggle for racial justice end with the passage of civil rights legislation in the 1960s, more recent scholarship has highlighted the persistence of racism and black political activism in later years. Local community studies by historians Emilye Crosby, Todd Moye, Cynthia Fleming, Hasan Jeffries, and Françoise Hamlin have examined ongoing freedom struggles that continued beyond the civil rights era in such places as Wilcox County, Alabama, and Sunflower County, Mississippi. These works reveal the depth of opposition to black equality that existed in the rural South, the ongoing challenges facing impoverished communities, and continued racial disparities. Complicating the popular notion that the civil rights movement ended racism in the United States, they demonstrate how white supremacists obstructed further progress and perpetuated inequality after the 1960s.11

Other scholars have shown how racial ideologies took new forms as overt expressions of bigotry became less acceptable. Joseph Crespino’s study of the ways white Mississippians adapted to the end of Jim Crow demonstrates important connections between opposition to racial equality and the rise of the conservative movement in the late twentieth century. Analyses by Kevin Kruse and Matthew Lassiter of white suburbanites’ reactions to federal civil rights enforcement provide insight into the ways segregationist arguments evolved into defenses of individual liberty and limited government that seemingly had no racial motivations. Rather than asserting that African Americans were inherently inferior to white people, as they had in the past, opponents of the freedom movement expressed support for integration while resisting every practical means of achieving it on the grounds that these represented a tyrannical use of federal power. Through this process, a form of “colorblind racism” replaced the blatant forms of discrimination of earlier decades. Rejecting the proactive measures that were needed to overcome racial inequality, policy makers instead moved to adopt racially neutral approaches that effectively froze existing disparities in place.12

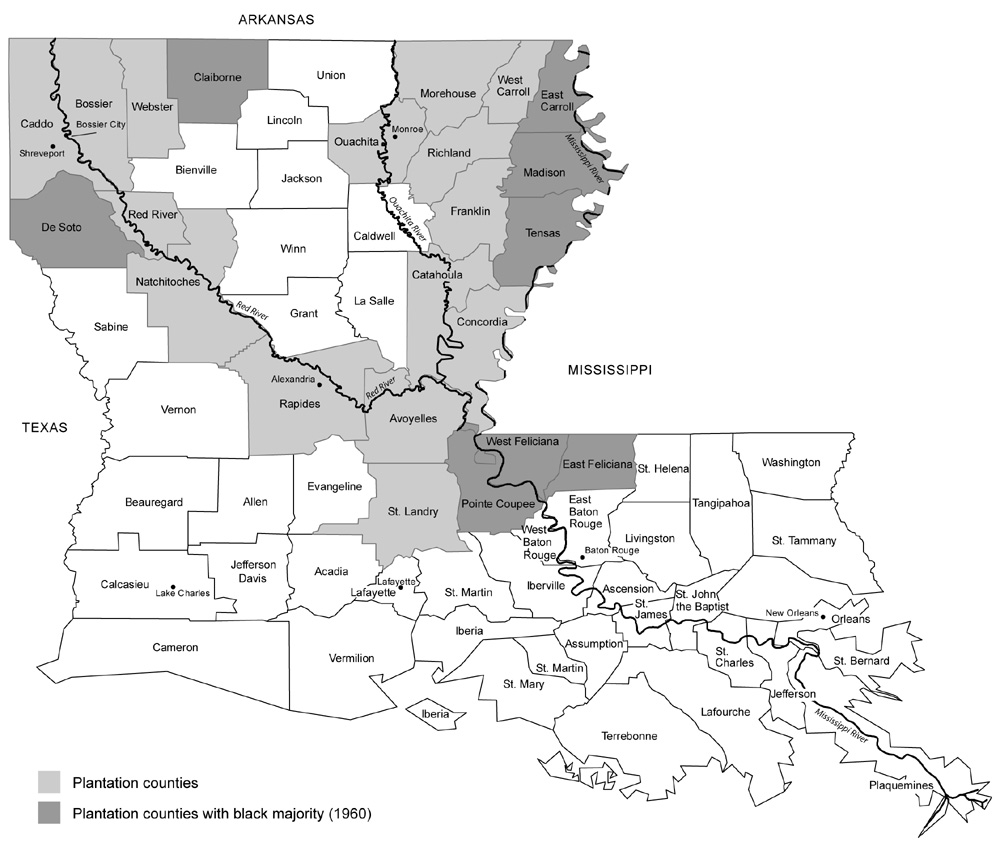

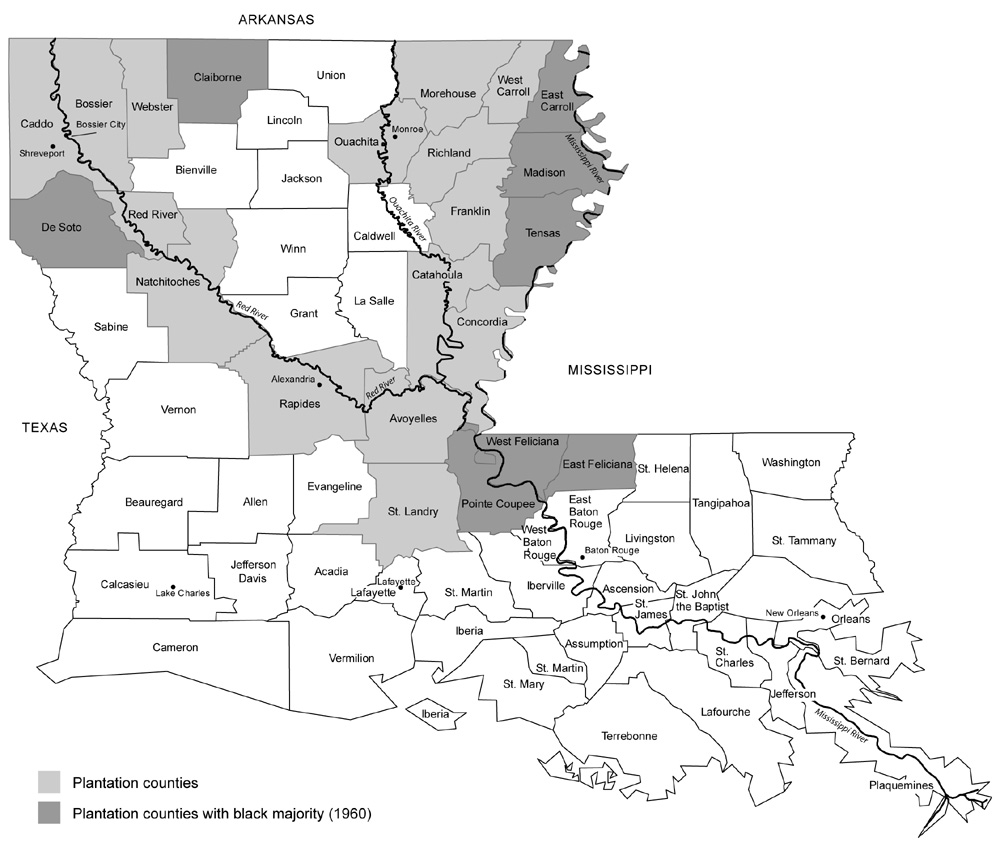

Map 1. Louisiana Cotton Plantation Region

Sources: Bureau of the Census, Special Report of Multiple-Unit Operations in Selected Areas of Southern States (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1947), xviii (fig. 10); Gavin Wright, Old South, New South: Revolutions in the Southern Economy since the Civil War (New York: Basic Books, 1986), 83; Charles S. Aiken, The Cotton Plantation South since the Civil War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 6; Bureau of the Census, Census of the Population: 1960, vol. 1: Characteristics of the Population, pt. 20: Louisiana (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1963), 24–25 (table 13).

Map 2. Mississippi Cotton Plantation Region

Sources: Bureau of the Census, Special Report of Multiple-Unit Operations in Selected Areas of Southern States (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1947), xviii (fig. 10); Gavin Wright, Old South, New South: Revolutions in the Southern Economy since the Civil War (New York: Basic Books, 1986), 83; Charles S. Aiken, The Cotton Plantation South since the Civil War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 6; Bureau of the Census, Census of the Population: 1960, vol. 1: Characteristics of the Population, pt. 26: Mississippi (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1963), 24–25 (table 13).

Map 3. Alabama Cotton Plantation Region

Sources: Bureau of the Census, Special Report of Multiple-Unit Operations in Selected Areas of Southern States (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1947), xviii (fig. 10); Gavin Wright, Old South, New South: Revolutions in the Southern Economy since the Civil War (New York: Basic Books, 1986), 83; Charles S. Aiken, The Cotton Plantation South since the Civil War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 6; Bureau of the Census, Census of the Population: 1960, vol. 1: Characteristics of the Population, pt. 2: Alabama (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1963), 24–25 (table 13).

Continued racism necessitated continued activism long after the 1960s. Historians such as Thomas Peake, Mark Newman, Stephen Tuck, Chris Danielson, and Timothy Minchin have shown how ongoing pressure from civil rights groups and individual activists was crucial to realizing the rights set out in the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and National Urban League all continued to act as important voices for African Americans in the post–civil rights era, drawing attention to persistent discrimination and lobbying Congress on issues relating to racial justice. Although internal conflicts and financial troubles destroyed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and badly weakened CORE in the late 1960s, small cadres of local activists and a few outside supporters continued the freedom struggle in the communities these groups had helped mobilize earlier in the decade. The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), Delta Ministry, and Selma Inter-Religious Project were among dozens of organizations that fought to enhance rural black southerners’ political and economic rights in the post–civil rights era. The Scholarship, Education and Defense Fund for Racial Equality (SEDFRE), a national organization founded by former CORE members, supported these efforts by providing leadership training and technical assistance to community groups and black elected officials in the 1970s.13

In addition to securing equality under the law, a central concern of the freedom movement was economic justice. African Americans did not have access to the same educational and employment opportunities as white Americans during the Jim Crow era, leaving them at a disadvantage even after civil rights legislation outlawed racial discrimination. For these reasons, activists called on the federal government to create employment, provide job training, assist unemployed people, and foster broader economic development in rural southern communities. A small step toward addressing these issues came in 1961 when Congress created the Area Redevelopment Administration to provide aid to distressed areas through grants and loans that encouraged new business development, infrastructure investments, and job training programs. Local political and business leaders prepared the plans and made the decisions that determined how to allocate these resources, however, and they paid little attention to the needs of poor and nonwhite people. When authorization for the agency expired in 1965, its responsibilities passed to the newly established Economic Development Administration (EDA) in the Department of Commerce. Although local governments still initiated projects, federal officials decided which ones to fund and enforced antidiscrimination provisions that regulated use of the money, allowing for more participation by African Americans.14 Pressure from civil rights activists also helped inspire the federal government’s War on Poverty, launched in 1964 with the Economic Opportunity Act. One of several measures aimed at realizing President Lyndon Johnson’s vision of a “Great Society” that offered all citizens the same chance of success, the legislation created the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) within the executive branch of government and provided for direct federal funding of programs initiated by local community groups, including many that were led by participants in the black freedom movement. Recent scholarship by Annelise Orleck, Susan Youngblood Ashmore, William Clayson, and others has shown that the OEO’s community action programs (CAPs) were key sites of contestation in the fight for racial and economic justice, making the War on Poverty an essential element in the story of post-1960s black political activism.15

My work brings these historiographical strands together in a regional study emphasizing the centrality of labor displacement in shaping developments in the plantation counties after 1965. Existing accounts tend to treat the changes in southern agriculture as the backdrop or a side note to other events rather than the driving force behind the actions of white supremacists and social justice activists in this period. Leaving these shifts in the political economy unexamined creates the impression that the motivations of those who resisted the freedom struggle were static and aimed at preserving the racial hierarchies created by slavery and Jim Crow.16 A full understanding of this period requires moving beyond frameworks that examine ongoing struggles over race and rights simply as extensions of earlier conflicts to acknowledge the transformation in class relationships that occurred with the conversion of black southerners from cheap labor to unneeded labor. Presuming that white leaders’ goals were unchanging makes the policies they pursued seem like attempts to maintain timeless racial traditions rather than what they really were: a concerted effort, necessitated by new circumstances, to cast off a large population of unemployed and poor people. As this book shows, plantation owners’ responses to the civil rights revolution reflected economic and political motivations rooted in the social context of the late twentieth century, not nostalgia for the late nineteenth century. Moreover, the rationalizations they offered foreshadowed a national shift in thinking that occurred as the United States entered a period of economic restructuring that threw millions of people out of work in the 1970s and 1980s. What happened in these rural counties established precedents for the treatment of other Americans whose lives were disrupted by the vicissitudes of the market in later decades.

On the other side, this book challenges the notion that economic marginalization was the inevitable outcome for workers whose labor was no longer needed and that nothing could alter sharecroppers’ fate once the forces of agricultural modernization took hold.17Rural black southerners were not powerless victims of inexorable processes that were beyond anyone’s control. They understood that political decisions rather than inalterable laws of supply and demand created impoverished people and communities. These activists offered innovative solutions to social problems that could have placed the region—and the nation as a whole—on a significantly different trajectory if they had not encountered such strong resistance from opponents. The conflicts that ensued in the plantation counties after the passage of civil rights legislation and their long-term consequences for white as well as black Americans demonstrate how race and class domination act in concert as intertwined and mutually reinforcing systems of oppression. Post-1960s social justice activism reflected participants’ awareness of these connections and the need to address them simultaneously through efforts to enhance economic security along with racial equality. The initiatives undertaken in these decades were not futile or insignificant, and they provide useful lessons for citizens seeking to fully realize the unfulfilled promises of the civil rights era.

Chapter 1 of this book describes the extreme hardships facing plantation workers as they made the transition from free labor to displaced persons simultaneously with the rise of the civil rights movement and the demise of Jim Crow. White supremacists responded to black civil rights gains by accelerating the displacement of farm families from the land and blocking efforts to provide alternative means of support for thousands of unemployed people who were left without homes or income. Southern welfare and economic development policies were designed to encourage black out-migration from the region, enabling wealthy white families whose fortunes were built on exploiting black labor to avoid responsibility for those workers once they were no longer needed. At the same time, reducing the number of African Americans living in the plantation counties helped minimize the threat posed by black political empowerment. By the mid-1960s, these policies had forced hundreds of thousands of African Americans to leave the region and generated rising unemployment and poverty rates for those who remained.

Local activists and their allies from outside the South knew that political rights alone could not solve these problems. Civil rights legislation did not represent the culmination of their goals but was instead a necessary starting point from which to launch a new phase of the freedom struggle focused on securing economic justice. They envisioned a reordering of the region’s political economy along lines that ensured a living wage for working people, adequate social supports and retraining programs for the unemployed, a tax system that generated the revenues needed for public investments in education and infrastructure, and opportunities for all citizens to participate in democratic decision making. As outlined in Chapter 2, activists responded to the economic crisis in the rural South by publicizing widespread hunger and poverty and pressuring federal officials to act. African Americans who had lived and worked in the plantation counties for generations made it clear that they did not want to leave and argued that they had a right to remain in their home communities instead of being forced to move elsewhere to look for jobs. They proposed alternatives to out-migration that called for increased public expenditures on education, job training, and improved social services for displaced workers. Their lobbying and clear evidence of the misery that resulted from the policies pursued by state and local governments in the plantation regions convinced the federal government to step up antipoverty efforts.

Chapter 3 examines the impact of the War on Poverty in the plantation counties and the threat that it posed to the people in power. Direct access to the OEO’s grant-making divisions enabled black residents to bypass racist administrators of state and county offices who had previously controlled access to federal assistance, bringing millions of dollars into impoverished areas. Antipoverty initiatives provided services and job opportunities for poor people, encouraging displaced laborers to stay in the South and work to improve conditions in their communities. In its first few years, the radical potential of the War on Poverty was demonstrated in inventive and effective projects that included early childhood development programs, cooperative farms and businesses, and comprehensive health services for low-income people. The OEO’s mandate to include representatives of the poor in program planning enabled rural black southerners to directly influence the distribution of resources in their communities for the first time in their lives. All of this threatened the interests of regional elites, and they responded by attacking the programs. Opponents used exaggerated (and often fabricated) charges of corruption and mismanagement to paint the War on Poverty as a waste of taxpayer money and undermine public support for the effort. Political pressure and budget cuts weakened the OEO’s support for black southerners’ rural development projects and generated some bitterness among participants in antipoverty programs. By the end of the 1960s, many activists were disillusioned with government efforts to solve social problems and sought alternative solutions that fostered black autonomy and economic independence.

Contrary to racist perceptions of African Americans as lazy welfare recipients who preferred dependence on government assistance to making a living on their own, black southerners were intensely interested in self-help efforts that enabled them to break free from white control. Chapter 4 examines the rise of the low-income cooperative movement and the opportunities it offered for rural poor people to take charge of their economic destiny. In response to layoffs and evictions, activists formed cooperative enterprises that provided employment to people who lost their jobs because of their political activities. More than just a survival tactic, cooperatives were a crucial part of the freedom struggle in the post–civil rights era. They represented an attempt to establish a measure of economic independence for rural poor people and thus facilitate political participation in a region where many African Americans still feared losing their homes or livelihoods if they tried to challenge the social order. Creating black-owned businesses founded on cooperative principles also demonstrated that alternatives existed to capitalist economic structures that exploited and then discarded black labor. Despite some internal weaknesses and hostility from white supremacists that hindered their effectiveness, cooperatives showed significant promise as a model for alleviating rural poverty. In the late 1960s, activists formed the Federation of Southern Cooperatives (FSC) and secured funding from the OEO and the Ford Foundation to pioneer a comprehensive plan for regional economic development that aimed to establish cooperatives as the path forward to a more equitable and sustainable future for rural poor southerners.

As the cooperative movement emerged and coalesced into the FSC, the national political winds shifted direction when voters elected a more conservative Congress in 1966 and gave the presidency to Republican candidate Richard Nixon in 1968. Chapter 5 describes how the political discourse of the 1970s echoed the sentiments expressed by southern opponents of the civil rights movement and the War on Poverty in the 1960s, tracing changes in federal policy that reflected the growing acceptance of these ideas among government officials and the population at large. Citing the need to halt the trend toward federal intervention in the economy and other areas of American life, Nixon proclaimed an era of “New Federalism” that reduced funding for antipoverty programs and restored control over economic development to state and local governments. These moves neutralized the transformative potential of the War on Poverty and left existing power relations intact, leaving poor people without strong advocates in government or adequate assistance during a decade of rising unemployment and economic distress.

As shown in Chapter 6, Nixon’s reversal and the difficulty of securing private funding in a faltering economy hindered the FSC’s attempts to expand and build upon the achievements of the low-income cooperative movement. Even so, the organization made significant contributions to the freedom struggle in the post–civil rights era. The services it provided to cooperatives ensured the survival of many black-owned enterprises and encouraged African Americans to remain in rural southern communities instead of migrating away. Its Rural Training and Research Center in Sumter County, Alabama, trained hundreds of cooperative managers and members, providing vital services to small farmers and other rural people who were mostly ignored by federal agricultural agencies. The FSC’s activist staff continued the struggles for civil rights and social justice by working to increase black representation in economic development initiatives, encouraging black political participation, and organizing local communities to fight persistent racism. Predictably, these efforts generated resistance from powerful white southerners. In 1979, accusations that the FSC was misusing government grants to fund political activities sparked an eighteen-month-long investigation that disrupted and weakened the organization, despite finding no evidence of wrongdoing. The federation’s troubles were compounded in the 1980s with the election of conservative Republican Ronald Reagan to the presidency and an even sharper shift to the right in the national government.

Chapter 7 analyzes the Reagan administration’s approaches to social problems and their consequences for rural poor southerners. Seeking to end excessive government interference in the economy, the president and his advisers cut taxes, weakened civil rights enforcement, and reduced funding for social programs that served low-income Americans. Like his political allies in the South, Reagan was convinced that private enterprise and market forces were the most efficient mechanisms for creating wealth and distributing resources. Such policies worked no better in the 1980s than they had before the 1960s, however, and conditions in the plantation counties worsened during this decade. At the end of Reagan’s second term, the region was still plagued by unemployment, poverty, inadequate health care, substandard housing, and out-migration. The FSC and other social justice organizations did what they could to alleviate the crisis, but budgetary constraints and the indifference of the nation’s political leaders posed massive obstacles to their efforts. Although the FSC survived and continued its work into the twenty-first century, it was never able to complete the social revolution that its founders hoped to bring about in the 1960s.

Chapter 8 examines connections between the experiences of black workers in the rural South and those of other Americans in the late twentieth century. Antigovernment sentiment and extreme individualism of the type promoted by opponents of the freedom struggle made their way into mainstream thinking on the subjects of unemployment and poverty after the 1960s. Like their southern counterparts, white northerners reacted angrily to federal initiatives aimed at integrating their schools and neighborhoods, generating a growing antipathy toward government. Candidates for public office found that opposing federal overreach, calling for cuts in social programs, and blaming poor people for their own problems were effective methods for attracting votes both within and outside the South, even as many Americans faced layoffs and declining job prospects in deindustrializing communities. At the same time, a stagnant economy that seemed impervious to policy makers’ efforts to revive it opened space for laissez-faire theorists to promote a more hands-off approach. Economic policy in the 1980s and 1990s emphasized spending cuts, deregulation of businesses, and evisceration of the social safety net rather than attempts to boost demand for goods and services by raising incomes. These decisions threatened Americans’ economic security and generated increasing inequality throughout the United States, undermining the purchasing power of consumers and creating a debt crisis that caused the near collapse of global financial institutions in 2008. When the resulting recession threw millions of people out of work, opposition to government intervention in the economy prevented Congress from adopting the kinds of creative solutions to poverty and unemployment that existed in the 1960s. As noted in the Conclusion, however, the FSC’s social justice agenda lived on in efforts to support family farms and sustainable agriculture as well as renewed interest in the cooperative business model as an alternative to existing economic structures. The political and ideological struggles examined in earlier chapters of this book thus left lasting legacies on both sides of the debate.

Developments in the rural South after the mid-1960s served as a rehearsal for similar processes that eventually affected other Americans in the era of deindustrialization, globalization, and the rise of finance capitalism at the turn of the twenty-first century. Participants in these struggles raised and tried to answer questions that remained relevant decades later, offering contrasting theories regarding the causes of poverty and inequality, the role of government in the economy, and the ability of free markets or government initiatives to fully attend to human needs. The outcomes had consequences for all the nation’s people, not only for African Americans. Examining how residents of the plantation counties adapted to the social transformations that shook their world in the mid-twentieth century and paying attention to the ways that racial, economic, and political concerns intersected with one another enhances our understanding of ongoing debates over how to deal with the displacement of large numbers of workers during periods of economic restructuring.