Chapter 6: To Build Something, Where They Are

The Federation of Southern Cooperatives and Rural Economic Development

As the actions of federal officials threatened to negate earlier achievements by shifting responsibility for solving rural poverty back to local officials and private sector actors, participants in the low-income cooperative movement moved to coordinate their efforts more effectively and continued to craft their own solutions. The Federation of Southern Cooperatives brought the disparate groups that had been forming in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi together into an umbrella organization that promoted cooperative enterprise, provided training and financial assistance, advised members, lobbied for changes in federal policy, and secured funding for the movement from government agencies and private foundations. Initially hoping to gain support for a comprehensive rural development plan to revitalize the plantation regions and put displaced workers on a path toward economic self-sufficiency, cooperative leaders found they were operating in a very different political context than had existed earlier. Federal officials were less willing to aid cooperative efforts, and tight economic times made it difficult to secure the needed resources, even from sympathetic supporters of the movement in the 1970s.

At the same time, the FSC’s determination to ensure that African Americans retained control over their own projects and the disillusionment generated by the federal government’s fading commitment to the War on Poverty created tensions between the organization and potential funding sources. Early assistance from the OEO and the Ford Foundation enabled the federation to experiment with the cooperative model and demonstrate its promise for improving the lives of rural poor people, but when the FSC tried to secure funding to expand on this work, it encountered resistance from those who claimed to share its mission. The resulting conflicts and FSC leaders’ reluctance to scale back their agenda to please financial backers cost the organization a considerable amount of support, leaving it struggling to raise funds and serve its members. Continued attempts by opponents to obstruct the cooperative movement also hindered the federation’s efforts. Despite these difficulties, the FSC acted as an effective vehicle through which thousands of rural black southerners secured adequate incomes, job training, decent homes, and political representation for themselves and their children in the post–civil rights era.

By the late 1960s, cooperative organizers had acquired considerable experience in helping poor people establish successful business enterprises, along with a keen sense of how fragile these new self-help organizations were. Multiple obstacles threatened the long-term survival of cooperatives, including financial insecurity, the limited business acumen of members, internal suspicion and mistrust, and external hostility from opponents. The SCDP’s efforts to provide loans, technical assistance, and training to cooperatives in four states addressed some of these problems, but it was too small to meet the needs of the growing cooperative movement. The program’s creators understood from the start the necessity for a larger organization that could combine poor black southerners’ resources on a region-wide basis.

In February 1967 representatives from twenty groups met in Atlanta, Georgia, to form the Federation of Southern Cooperatives as a central service organization to meet the financial, educational, and technical needs of low-income cooperatives. The federation was officially chartered a few months later to operate in the District of Columbia and eleven southern states: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Texas. After opening an office in Atlanta in 1968 and securing several small foundation grants, the FSC began providing services to twenty-two member cooperatives. A research and technical assistance grant from the OEO enabled it to expand operations, and by January 1969 it had grown to fifty members.1

Headed by SCC’s Charles Prejean, the FSC worked closely with A. J. McKnight’s group in the states where activities of the two organizations overlapped. Prejean was born and raised in Lafayette, Louisiana, one generation removed from sharecropping. The poverty of his parents and grandparents deeply disturbed him, especially since they worked so hard for so little reward. As he watched his grandfather age and give up his farm labor job, Prejean was saddened that the old man “had nothing really left in life. . . . It seemed as if there was a person who had worked all his life and his value to society was as a worker. Once that value was no longer there he did not seem to have a place in society. I didn’t want that to happen to me or anybody else.” Prejean entered a Catholic seminary at the age of 13 with the idea of working for social justice in his rural community, but left after completing his high school training because he thought he could make a better contribution as a layperson. He met McKnight as a teenager when the priest was stationed in Lafayette in the 1950s and became involved in cooperative organizing and civil rights work under the older man’s mentorship. After completing college and working as a teacher for two years, Prejean went to work full-time for SCC, focusing on outreach and helping people set up credit unions.2

Other FSC organizers had similar activist backgrounds. According to Prejean, civil rights leadership and cooperative leadership overlapped in many rural southern communities, and local chapters of the NAACP, SCLC, SNCC, and CORE always included people who were interested in economic development as well as desegregation and voter registration. Late in 1969, with SCEF’s Ford Foundation grant due to expire in a few months, the FSC absorbed the SCDP’s programs and staff. John Zippert, Mildred and Lewis Black, Ezra Cunningham, and other activists who had gained their initial organizing experiences on civil rights projects continued their participation in the freedom struggle through the FSC. As the federation explained in one of its annual reports, the cooperative movement was poor people’s “economic response to the Civil Rights Movement,” working to capitalize on and supplement the legal and political rights black southerners had won in the mid-1960s. To Prejean, cooperatives were the obvious solution to the dilemmas confronting poor people in the region. “It just makes so much sense,” he stated. “If a community is experiencing common problems with little resources, it seemed to us it made so much sense to pool resources and use them to satisfy a common need.”3

Providing the expertise and resources needed for hundreds of existing and aspiring low-income cooperatives was a huge project. The FSC attempted to beg, cajole, and shame federal agencies and private foundations into providing the millions of dollars required to overcome the lingering effects of racism in the South, but its work was never adequately supported. The direction of national politics in the 1970s was not conducive to the continuation of innovative solutions to rural poverty that had been possible in earlier years. Poor black people lost a key ally in their struggles for economic justice as Nixon set about reorganizing the OEO and returned control over federal programs to the states and traditional government departments. Beset by the costs of the Vietnam War and anguished by the sluggish economy, political leaders were in no mood to receive requests for significant expenditures to help African Americans, even if they supported the FSC’s goals of enabling black self-help and autonomy. Along with CAPs and other Great Society projects, cooperatives faced an uncertain future and indifference from government officials in the decades after the 1960s.

Trends toward greater belt-tightening were also evident in the foundation world. In 1969 Congress moved to more closely regulate tax-exempt philanthropic organizations in an attempt to prevent wealthy Americans from using them as tax havens. Although there had been some instances of abuse that were legitimate cause for concern, the reforms proposed by the House Ways and Means Committee in May risked crippling the ability of the nation’s charitable institutions to fund activities aimed at solving social problems. Some of the proposed changes, such as a ban on efforts to “influence” elections or government policy, seemed motivated by a desire to cut off support for voter registration and other forms of civil rights activism that were encouraged by the Ford Foundation, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, and other liberal groups. Although protests from the philanthropic community convinced legislators to modify the bill, the final version of the Tax Reform Act of 1969 had the effect of reducing the amount of foundation funds that were available and limiting their use.4

From the start, then, the FSC operated in an economic and political climate that did not favor an expansion of social programs or attempts to empower poor black people to take control of their lives and communities. The small amounts of money the FSC did manage to secure from government or private sources often came with strings attached that restricted spending on vitally needed services. In July 1968 Charles Prejean told a Field Foundation executive that grants from two other foundations did not allow for emergency loans to struggling cooperatives, despite the emphasis the FSC had put on this in its grant requests. Although the FSC had used some of its general support funds to make a few loans, requests for assistance exceeded its ability to help its members. For the most part the organization was limited to providing accounting assistance and researching new products and markets—activities that would be useless if the cooperatives failed for lack of funds. “The response to the Federation has been great,” Prejean wrote, “but I am beginning to become frustrated because we have resources to help with so few of the problems of cooperatives.”5

Activists estimated the credit needs of existing cooperatives at $2 million and pointed out that much more money would be needed if the movement continued its rapid growth. With traditional lending agencies refusing to make loans to poor people’s enterprises, the FSC approached the OEO and the Ford Foundation for help in forming a special development bank to serve the low-income cooperatives. At a meeting on 18 January 1969 the OEO agreed to provide $500,000 that the FSC could use to meet the capital needs of its members, and the Ford Foundation made a tentative commitment to invest in the new cooperative bank, contingent on a feasibility study. The EDA contributed $100,000 to the project to cover administrative costs, and several other foundations, unions, and churches also expressed their willingness to invest in the venture. Participants agreed to allow the cooperatives to have controlling ownership of the bank and to define its mission as serving “human needs, with financial criteria no more limiting than necessary to the viability of the institution as one which can attract the capital needed for eventual self-sufficiency.”6

The end result of these efforts was the creation of the Southern Cooperative Development Fund (SCDF), a for-profit corporation presided over by A. J. McKnight, late in 1969. Using part of the OEO grant to guarantee a return of at least 50 cents on the dollar, McKnight and his staff secured $1 million from foundation and insurance company investors over the next two years. Cooperatives could request loans from the fund through the FSC’s state representatives, who helped them gather the information and documentation necessary to file an application. To join the SCDF, cooperatives purchased voting shares in the fund at $100 each, based on the size of their memberships. Borrowing money from the fund required the purchase of additional shares worth 5 percent of the amount of the loan. The interest rate on loans was 10 percent annually on the unpaid balance, with the possibility of interest subsidies that could lower the rate to 6 percent for cooperatives needing additional assistance. By the mid-1970s the SCDF had made loans totaling almost $3 million to its members, and the combined assets of the fund and its subsidiaries had increased to $8 million.7

The SCDF acted as a financing agency to the cooperative movement while the FSC provided technical assistance. To join the FSC, cooperatives had to be made up primarily of poor people, be incorporated entities, and pay annual membership dues. Membership in both the member cooperatives and the FSC was open to all people regardless of race. The FSC’s staff was interracial, but most of the cooperatives were all black. As Charles Prejean explained, the racial imbalance existed because most white southerners were “reluctant to join with blacks at this point in time.” Although the FSC’s immediate priority was to help the struggling new cooperatives succeed as self-sustaining business enterprises, its long-range goal was to create an economic and political base for black southerners to enable them to tackle such broader social problems as housing, health care, and jobs. By pooling their resources, people with little money or expertise of their own could gain more power over their lives and create alternatives to a marginal existence as unneeded labor.8

In April 1969 the FSC reported on some of the results of this approach after its first year of operation. The farmers’ cooperatives had purchased 9,000 tons of fertilizer at significant savings for their members. Participation in several gift shows in New York had generated orders for the handcraft enterprises. A $2,000 loan to the Greene-Hale Sewing Cooperative enabled the group to buy new machines and move into a bigger building, and the FSC also provided training to the co-op’s manager, staff, and board. Thirteen other member cooperatives benefited from FSC loans and grants totaling $332,240. The organization’s research efforts identified promising new products and markets, and it was developing a library of educational materials to help with training and technical support. It was a promising start, but much more remained to be done. The executive director’s report stated, “Although the efforts were 100%, they still only scratch the surface of the problems that are confronting us. The cooperative approach to problem solving calls not only for an adjustment to the evils of the present institutions, but for substitutions in some cases.” The theme of the 1969 annual meeting, “Another Way for Us,” reflected the FSC’s belief that building alternative social structures was both possible and necessary to meet the needs of its constituents.9

The government and foundation grants that sustained the FSC through this early phase were intended to help the organization to experiment with the cooperative model while developing a comprehensive program for rural development in the South. Drawing on its experiences with the member cooperatives, the FSC developed a five-year plan with an estimated cost of $6 million per year and submitted it to the Ford Foundation, the OEO, and several other funding sources in May 1969. None of the agencies were willing to invest the entire amount requested, and at the suggestion of Ford program staff the FSC rewrote the proposal and parceled out its various components to different organizations. The Ford Foundation agreed to provide $750,000 for services to a small number of agricultural cooperatives, and the OEO supplied a $500,000 grant to support the handcraft, credit union, and consumer cooperatives.10 Though the funds were only a fraction of what was needed, the FSC hoped to gain further support once it had demonstrated the viability of its approach.

Over the next two years, the sixteen farmers’ cooperatives covered by the Ford grant benefited from an intensive training program designed to improve the business skills of their managers and members, and the FSC hired a marketing specialist to link them to potential customers such as chain stores, food-processing companies, minority-owned businesses, and buying clubs. Field staff showed farmers how to improve crop yields and diversify into livestock production to supplement their incomes. The FSC’s purchasing program saved farmers money on supplies, with a collective reduction in spending of $68,000 on fertilizer alone. In 1971 the cooperatives made a total of $1,240,000 in sales and paid out $745,000 to farmers and harvest workers. In its report to the Ford Foundation in October, the FSC stated that its models had produced “viable business operations generating significant incomes for small farmers who had previously been written off by most conservative, conventional, unimaginative, theoretical economists.”11

In some respects the FSC acted as a substitute for federal agricultural agencies that had long ignored the needs of rural poor southerners, black and white. Despite new regulations banning racial discrimination, administrators of USDA programs continued to neglect black farmers or provide inferior service. The FES, the FmHA, and the state land grant colleges whose research departments focused on aiding large agribusinesses showed scant interest in assisting low-income cooperatives and sometimes actively obstructed them. The FSC and its members faced roadblocks everywhere they turned for help. Charles Prejean reported in 1970 that even the federally capitalized Bank for Cooperatives “will not touch us because we are poor and high risk.” Faced with this lack of support from the agencies that were supposed to serve rural people, the FSC was compelled to develop its own research programs, create its own financial institutions, and hire its own specialists in accounting, marketing, horticulture, and other fields.12

After successfully operating a training program for small farmers that taught new techniques and management skills to 1,285 operators in seven states in 1971, the FSC began planning for the construction of a permanent agricultural demonstration and training center in Sumter County, Alabama. The goal was to experiment with activities such as cattle production, feeder pigs, catfish farming, row crops, and vegetable production using irrigation and greenhouses to show farmers how to maximize the use of small amounts of land. In addition, the FSC planned to initiate manufacturing projects at the site to provide jobs and training in furniture making, metal stamping, and electronics. To critics who charged that the project duplicated services already provided by the USDA, the FSC responded: “Show us the USDA sponsored facilities that are responsive to the needs of small farmers; show us the facilities that are disseminating information useful to the small farmer in a form and context he can understand; show us the facilities that are oriented toward providing techniques and training to small farmers in enterprises that can produce new income for their families.”13

With the OEO grant and assistance from several small foundations, the federation continued its work with nonagricultural cooperatives. In Alabama, the FSC experimented with using the cooperative model to promote an integrated approach to antipoverty efforts and economic development by helping a group of displaced farmworkers to initiate self-help housing and other projects. In 1967 tenant families on a plantation in Sumter County who had asked their landlord for their share of cotton allotment payments were forced off the land after he leased their plots to a paper mill company in retaliation. Some of the families moved north, but NAACP and SCDP activists encouraged most of them to stay by providing temporary accommodation and other assistance. Forty families joined together to form the Panola Land Buyers Association (PLBA), and with Lewis Black’s help they located some land for sale in their home county. As John Zippert noted, it was rare to find white people in Alabama who were willing to sell land to African Americans. The owner of this particular tract was engaged in a feud with local elites and viewed selling it to a black group as an act of revenge.14 After three years of legal battles the PLBA finally gained title to 1,164 acres of land near Epes and applied for a cooperative housing loan from the FmHA. The PLBA also allowed the FSC to locate its Rural Training and Research Center (RTRC) at the site. Within a year of the purchase the federation had built offices, classrooms, dormitories, an auditorium, and a cafeteria at the center, along with greenhouses and barns for its demonstration projects. In September 1971 the FSC’s program staff relocated to the facility so that they could more easily serve members.15

By 1972 the FSC had grown to 110 member organizations serving approximately 30,000 families. Its cooperatives were engaged in diverse enterprises ranging from handcrafts and bakeries to metal stamping and concrete brick manufacturing. The membership also included 20 cooperative stores and buying clubs with 4,000 participants in seven states. “Co-ops have meant survival to poor people in the rural South,” the FSC reported. “They have helped people to use the resources they have—land, labor, native intelligence to build something, where they are. . . . People can taste the freedom in this, and are willing to take on the responsibilities and the blessing that come with this choice.” Charles Prejean expressed his belief that FSC members were building a base for self-sufficiency and preparing rural poor southerners to participate in broader economic opportunities becoming available in the region. As some former opponents of the movement were starting to realize, these developments promised to benefit many other people apart from African Americans. Prejean noted that once cooperatives began making purchases from white-owned businesses, those enterprises began to grow, and more white southerners could see the value of the FSC’s work.16

Responses from the FSC’s rural poor constituents were positive as well. After one meeting where members voted to allow annual dues to be set on a sliding scale depending on how much people were able to pay, Prejean observed that while this might not provide much income, “it does indicate that our members are willing to support the Federation as much as they are able.” Sumter County resident Lillie Dunn Johnson described how her life was changed after an FSC field-worker came to her house in 1974 and asked if she wanted to learn to crochet. “At 61 years of age, being Black, old, and poor, I had nothing to do and no-where to go,” she stated. “The training not only cured my illness, it changed my way of thinking, my way of meeting people, my way of living.” Organizers’ civil rights backgrounds, their willingness to live and work in the region’s most impoverished counties, and their focus on empowering people to solve their own problems instead of telling them what to do earned them deep respect from participants. In an evaluation of a three-week training session for NBCFC members, Mississippian John Perkins expressed his appreciation for the FSC’s approach. “I feel that the Federation staff was really beautiful in its preparation and presentation of the training session,” he wrote. “John Zippert, Jim Jones, and Ralph Paige did a superb job in bringing about awareness within the membership. Their skills and dedications are unquestionable.” Federation staff reciprocated such feelings in expressions of appreciation for the cooperatives and families they worked for. In a letter to the Milestone Farmers Cooperative following a meeting with its members early in 1973, FSC marketing director George Paris praised the group’s enthusiasm and stated that he was “very impressed by the interest and participation of your cooperative members.”17

In addition to directly assisting cooperatives, the federation opened up other opportunities for local people that led to fulfilling careers in the movement. Ben Burkett grew up on a farm near Petal, Mississippi, during the civil rights era, earned a degree in agriculture from Alcorn State University in the early 1970s, and originally planned to follow others of his generation to Chicago or Detroit. When his father became ill he stayed to help tend the land, earning a good income until cotton and soybean prices dropped at the end of the decade. With many small farmers facing bankruptcy, Burkett and several other landowners formed the Indian Springs Farmers Co-op to purchase equipment together. The FSC helped them to incorporate formally and supported the farmers as they switched to growing vegetables and located markets for their produce. Burkett remained in farming for the rest of his life while also serving as state coordinator for the federation’s Mississippi cooperatives. He helped develop more co-ops there and in other states and traveled internationally with other FSC staff to exchange ideas and techniques with farmers in Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. Through his work with the FSC and as president of the National Family Farm Coalition, Burkett established a reputation as an innovator and mentor to other farmers, promoting sustainable farming techniques and the right of all people to adequate, nutritious food.18

Melbah McAfee was another Mississippi native who found her calling in working for the federation. McAfee’s parents grew vegetables and raised livestock on forty acres of land in Rankin County, where she developed a lifelong love for farming and a desire to advocate on behalf of family farmers. In 1972 she took a job as the FSC’s director of consumer cooperatives, moved to the training center at Epes, and spent the next three decades in various roles with the organization that allowed her to work on empowering rural communities through cooperative leadership development. McAfee helped form more than twenty-five co-ops in Mississippi and Louisiana, trained boards and members in cooperative principles, lobbied to bring affordable housing to low-income areas, and inspired others with her passion for social justice.19

Burkett’s and McAfee’s experiences were not unique. The FSC employed hundreds of local people from the communities it served, giving many of them their first experience in professional or skilled work. Some of these trainees stayed with the federation for decades, while others went on to become elected officials, government workers, teachers, lawyers, social workers, bank managers, and business leaders. These activists spread the federation’s ideals into other arenas, advancing the freedom struggle through their participation in mainstream institutions and as leaders of their towns, cities, and states.20

Foundation staff, government officials, and other outside observers recognized the FSC’s contributions to improving conditions in the rural South. Cooperative movement sage Jerry Voorhis praised the FSC at the 1971 annual meeting of the American Institute of Cooperatives for “doing a job of outstanding importance” in its efforts to help rural poor people stay on the land instead of migrating to northern cities. The Field Foundation’s Leslie Dunbar informed Charles Prejean: “All of us at Field are greatly impressed by what the Federation has accomplished, and by the spirit in which and through which it has been done.” A program adviser in the manpower training division of HEW who had helped secure funding for a project to train cooperative managers lauded FSC staff for their “competence, perseverance, and dedication to the cause of social equality and economic progress” and predicted that FSC programs would become “one of our most significant manpower efforts for their effect on the economy of numerous rural hamlets.” Buoyed by such expressions of support, the FSC announced in its 1972 annual report: “We have arrived. . . . Our 1971–72 fiscal year . . . marked the beginning of our acceptance at the local, state and national levels as ‘the’ beacon for rural economic development.”21

Despite its record of achievement, the FSC still struggled to get financing for its activities. The Ford Foundation’s cautious approach and the lack of confidence in poor people’s abilities shown by some of its staff frustrated Charles Prejean to the point where he admitted to becoming “very obnoxious, hallucinatory and unreasonable” in his communications with the organization. Many people at the foundation held the FSC in high regard, but they had to balance their desire to support the cooperative movement against other groups’ demands for the limited social investment funds that Ford gave out each year. Other Ford staff members expressed skepticism about the viability of the low-income cooperatives or worried that the FSC’s goal of fostering black self-sufficiency could undermine efforts to alter established institutions and make them more responsive to African Americans’ needs. A summary of one staff meeting where these concerns were discussed in February 1969 concluded that the FSC could potentially play a leading role in rural development efforts, but it was too early to tell. The consensus was that Ford should “go slowly before knighting any one group with the authority and resources to orchestrate the southern cooperative movement.”22

Ford’s wait-and-see attitude made little sense to Prejean and others at the FSC. These activists had worked closely with rural poor people since the early 1960s. They knew which approaches worked and which did not, and they had identified the kinds of support and resources that were necessary for the cooperatives to succeed. Yet no one seemed willing to provide those resources, and without adequate funding it was difficult to prove the long-term viability of the projects. As Prejean put it, “We said we could prove to you that we can make a cake if we had the ingredients necessary to make that cake. You said, make a cake, then we will give you the ingredients.”23

In 1971, believing that its work with the selected sample of cooperatives in the earlier grant had demonstrated the value of its programs, the FSC submitted a proposal asking for $3 million over three years. Once again foundation staff decided that the amount was too high and suggested rewriting the proposal to request $500,000 for one year. A disappointed Prejean told Ford staffer Bryant George: “We have written you a proposal reflecting the needs of the constituency of the Federation. . . . We have no intentions of writing another proposal.” To Prejean, Ford’s efforts to direct the FSC’s work typified the misguided paternalism of white liberals who believed they knew what was best for black people. Rather than expecting the FSC to conform to the Ford Foundation’s expectations, he suggested, administrators should embrace the chance to support programs that black people developed themselves.24 Prejean worried that partial funding for projects was almost as damaging to the cooperative movement as no funds at all. When poor people’s hopes were raised but they failed to receive the resources they needed to succeed, their confidence was shaken and they became discouraged. Support from people outside the movement was also jeopardized when cooperatives that could not secure the loans, staff, or advisers they needed did not perform as well as they might have. Far from helping the cooperative movement to succeed, the Ford Foundation and other funding agencies were setting it up to fail.

Prejean outlined these concerns in a letter to foundation president McGeorge Bundy appealing the program staff’s decision. He explained that Ford’s refusal to make a long-term commitment to the FSC had made it difficult for the Federation to recruit horticulturalists, economists, accountants, and other specialists it needed to provide technical support to its members. Highly trained workers who could command better salaries elsewhere were reluctant to join an organization whose funding and future were uncertain. The FSC could take the $500,000 Ford offered, but it was not enough to ensure success. Consequently, Prejean predicted, “Ford and other FSC funding sources will become more dissatisfied because we have not made these businesses self-sustaining operations. And it will not be important that we were given the wrong ingredients to achieve their desired results.”25

A. J. McKnight expressed similar views to foundation vice president Mitchell Sviridoff. The FSC’s work was vital to the success of the SCDF, McKnight stated, because it provided the assistance needed for cooperatives to become viable and repay their SCDF loans. He explained: “We have learned from previous experience that it does not suffice merely to loan money to the low income cooperatives. The loan must be supported with technical assistance, involving management, marketing and accounting assistance.” Inadequately funding the FSC risked placing the SCDF loans in danger. As McKnight pointed out, Ford had helped create the SCDF to provide credit to fledgling cooperatives, with the hope that once they became viable businesses they could qualify for loans from traditional financial institutions. He warned, “Without the supportive technical assistance during this period from the Federation of Southern Cooperatives to the cooperatives this objective will not be realizable.”26

Ford insisted that it could not increase the amount of the money it had offered or promise continued support to the FSC after the one-year grant expired. McGeorge Bundy blamed budget restrictions and the foundation’s annual funding cycle, noting that a three-year grant to the FSC would have to come out of one year’s budget, which would leave other organizations that were just as worthy of support unfunded. “We cannot pretend that we are making enough money available to make all of the cooperative endeavors work in the rural South,” he admitted, “but we want to continue to do what we can until resources of appropriate scale are made available.” Although Prejean continued to harbor reservations, the FSC’s board of directors decided that partial funding was better than nothing. Prejean submitted a revised proposal in July 1971, and Ford agreed to fund the FSC’s activities for another year.27

The FSC’s relationship with the OEO was plagued by the same problems it encountered with the Ford Foundation: inadequate and uncertain funding, skepticism regarding the viability of low-income cooperatives, and bureaucratic interference that hindered more than it helped the movement. After using its research and technical assistance grant to expand its staff and operations, the FSC applied for another $1.3 million to support an array of programs, including marketing assistance, health services, field training, and education for its members. Doubling the size of the previous year’s grant seemed like a reasonable request given the larger number of cooperatives the FSC now served, and activists also wanted to move beyond forming cooperatives to address broad social needs in rural southern communities. The OEO had itself increased the burden on the FSC’s support services by encouraging the development of cooperatives through its community action and rural assistance programs, then referring groups to the federation for help. Like the Ford Foundation, however, the OEO asked the FSC to scale down its ambitions and reduce its request to $500,000. According to Prejean, the decision had nothing to do with the FSC’s record, and OEO staff did not question the importance of its activities. “The reason that they give us is not that we deserve a cut, or that our proposal is not worthy of full consideration but that the Nixon Administration folks are cutting everyone so that they can support their own programs,” he stated.28

The reticence of both the Ford Foundation and the federal government grew partly from doubts that the low-income cooperatives could succeed. Even as some officials lent strong support to the movement, others expressed their belief that the unconventional economic models proposed by participants were doomed to fail. According to OEO staffer Elmer J. Moore, American agriculture was “a private enterprise industry” unsuited for cooperatives, and small farms only ensured poverty for those who lived on them. Moore’s colleague Joseph Kershaw expressed amazement that “the idea of putting people back on the land simply refuses to die in this town in the face of 100 years of history where just the opposite has been taking place.” He argued that the federal government could better address rural poverty by making “the inevitable transition away from the land less painful.” Similarly, a two-year study funded by the Ford Foundation from 1969 to 1971 concluded that the cooperatives were unlikely to ever become self-sustaining. The need for some form of outside assistance was a permanent feature, not a temporary condition, and according to these authors the only entities capable of providing it were the existing USDA agencies. They suggested that the foundation’s energies might be better expended on pressuring the FES to provide more assistance to cooperatives than funding the FSC. “Unless the help of U. S. D. A. is enlisted, the situation is hopeless,” they wrote. “Any attempts to duplicate its services strike us as unrealistic, however desirable they might be if U. S. D. A. proved to be unresponsive.”29

These types of analyses, reflecting profound ignorance of the southern political economy and the racist history of federal agricultural agencies, elicited furious responses from the FSC. Charles Prejean condemned the “vicious racist attacks” of the Ford-funded evaluators and told Bryant George: “If Ford must use this document to determine the credibility of the Federation and the credibility of Black people, and if Ford must use this to further conclude that we still come short of being human beings, then it has betrayed its commitment to humanity and has misused its responsibilities as a philanthropical organization.” To overcome the reservations of federal officials, the FSC pointed to successful examples of cooperative efforts in Europe, Asia, and Africa in addition to New Deal–era experiments in the United States to demonstrate the long-term viability of its projects. As the FSC’s southern rural project director William H. Peace III noted, cooperative members themselves were as keenly interested in self-sufficiency as outside funding agencies were in seeing them become so. Yet, he argued, the FSC could legitimately ask, “Why should we have to become self-dependent?” Taxpayers’ money paid for USDA services to the nation’s giant agribusinesses, yet the government demanded that poor people who benefited from the FSC’s programs pay for these themselves.30 Moreover, the corporate farms that some analysts held up as models of business efficiency were not self-sustaining. Without the millions of dollars in government subsidies that large growers received under the Agricultural Adjustment Act, these enterprises were no more viable than the low-income cooperatives.

The FSC’s staff and members considered that they had established a strong record of achievement and demonstrated the effectiveness of cooperatives in combating rural poverty and out-migration. They had done this in spite of the limitations imposed by inadequate finances, restrictions on the use of grant money, and bureaucratic meddling from people whose own expertise was limited. The doubts expressed by foundation and federal officials, their reluctance to fully support the cooperative movement, and their efforts to steer the FSC toward meeting their own agendas instead of serving rural black southerners generated resentment and caused some people within the movement to wonder what these agencies’ real motives were. In May 1970, for example, after the OEO’s southeast regional office refused to fund a management training proposal that it had encouraged FSC members to develop, Charles Prejean wrote, “It is inhuman to encourage poor people by promising them assistance that never comes. . . . But maybe we don’t have a poverty program that is designed to help the poor. Maybe it’s only called a poverty program whose main responsibility is to lie to people and maintain the affluent in lucrative job positions.”31

Such suspicions emerged again in August 1971, when the OEO announced its intent to conduct an evaluation of the cooperatives it had funded over the past five years as part of a plan to develop “a more effective rural cooperative program.” The agency chose a Massachusetts consulting firm that had no experience with cooperatives or rural development to carry out the study over fourteen months at a cost of $360,000. Officials then invited cooperative leaders to submit suggestions regarding the design and direction of the study. In the context of their past experiences with federal agencies and recent cuts in OEO programs, Prejean and many others concluded that the real reason for the evaluation was to provide a rationale for defunding cooperatives. John Brown Jr. urged FSC members to “unite in opposing this ‘Bull shit.’ They can spend the money, but they cannot have a valid study without our cooperation.” Brown noted that many cooperatives had received only one or two years of funding from the OEO and some, like SEASHA, had recently had their grants cut significantly. Often, he claimed, the OEO had provided no support at all, “just criticisms, confusion and other practices designed to create failure.” In Brown’s view, the OEO had already decided to withdraw federal assistance to cooperatives and the study was aimed at justifying this action. He argued that this money could be better spent by giving it directly to cooperatives to help them become self-sufficient.32

The FSC and SCDF both opposed the evaluation, as did SEASHA, SWAFCA, and three smaller cooperatives that were slated for inclusion. The cooperative directors called on supporters of the movement in Congress to pressure OEO officials to abandon the study and prepared a position paper outlining their objections. “Already this movement has been studied, monitored, and evaluated to death,” they stated. “We have spelled out our needs to our government incessantly. We have written countless proposals asking for assistance. We have either been ignored completely or given crumbs.” In a letter to Senator Hubert Humphrey, William H. Peace III emphasized the hopes for a better future that cooperatives had given rural poor southerners. “The cooperative as viewed by our people is not welfare, a hand-out, or somebody else doing it for you. . . . It is self determination, decision making, and participatory democracy in action. And it is the way to a better life for many of the people in our region.” What the cooperatives needed now, Peace argued, was not more scrutiny but the “support and commitment on the part of OEO and others for the low-income cooperative movement.”33

Federal officials attempted to assure cooperative leaders that the evaluation aimed to strengthen the movement, not destroy it. Office of Program Development director Carol Khosrovi pointed out that recent amendments to the Economic Opportunity Act provided for federal funding of cooperatives as “on-going, operational projects.” She argued that FSC members could provide federal administrators with valuable information about how to help cooperatives succeed. After a meeting with cooperative directors in November failed to convince them of the study’s potential value, Khosrovi and OEO chief Phillip Sanchez reiterated that the agency’s goal was not to attack the cooperative movement or justify withdrawing support. They encouraged cooperative leaders to help design and interpret the study, saying, “We offer this not as an accommodation but as a sincere effort to improve our service to the rural poor.”34

These expressions of federal goodwill eventually won over A. J. McKnight, who stated his willingness to allow the SCDF to participate in the study in December. Several other cooperatives also changed their position, and those with SCDF loans were included by extension whether they wanted to be or not. The FSC remained adamant in its opposition, however. Its staff referred OEO officials to research done by agricultural economists Roosevelt Steptoe, Ray Marshall, and Lamond Godwin that already provided much of the information the agency claimed to need regarding the problems facing low-income cooperatives and potential solutions. Charles Prejean insisted nothing could be gained from further studies, and that even if the evaluation yielded favorable conclusions, there was no guarantee the federal government would continue to fund cooperatives.35 With the FSC’s membership facing more pressing needs and the financial future uncertain, Prejean noted, its leaders could not in good conscience support the OEO’s diversion of hundreds of millions of dollars toward another wasteful evaluation. In a strongly worded letter to Sanchez, the FSC director again expressed his organization’s refusal to participate. “We will not cooperate with the study and will do all in our power to prevent ‘white folks from making other white folk (white consultant firms)’ rich at Black people’s expense,” he stated. Prejean expressed the same views to Khosrovi, threatening to do everything he could to discredit the study if it went ahead. According to Prejean, the FSC’s board, staff, and members were prepared to face whatever consequences resulted from this action, including the loss of OEO funds.36

As expected, the OEO retaliated by refusing to consider a proposal for refunding the FSC after its grant expired in June. At the same time, the FSC encountered renewed problems in its relationship with the Ford Foundation. In March 1972 foundation staff urged the FSC and SCDF to merge under the leadership of A. J. McKnight, with a single office located in either Atlanta or New Orleans instead of the three bases currently representing the cooperative movement in Lafayette, Epes, and Atlanta. As McKnight understood it, the request was more like an ultimatum, with Ford threatening to cut off funding for the FSC unless Prejean agreed to step down as director. Prejean refused and, with the support of his staff, proposed to move the SCDF headquarters to Epes instead. McKnight was unwilling to give up leadership of the SCDF, however, and his staff did not want to relocate. In April he suggested to Prejean that they work to preserve things as they were, with both men doing what they thought was best for their respective organizations while trying to coordinate their efforts whenever possible.37

The mutual hostility between Prejean and Ford executives intensified when Bryant George sought the FSC’s cooperation in a “formal evaluation” of its programs. According to George, a comprehensive assessment had not been undertaken since Ford first began to support the cooperative movement, and the foundation planned to remedy this in 1972. Two men who were “very sympathetic to the Cooperative Movement” were hired as evaluators, but they received an icy response when they attempted to obtain information from the FSC. On 26 April George warned Prejean that failure to cooperate with the evaluation would make it impossible for Ford to continue funding the organization. Although he admitted that allowing the evaluation to go forward would not necessarily guarantee funding either, George assured Prejean that Ford had “a strong and continuing program interest in the cooperative movement.”38

As was the case with the OEO, some cooperative leaders suspected that the Ford Foundation’s expressions of support masked a hidden agenda aimed at destroying the movement. Lewis Black noted that Ford and the cooperatives had enjoyed a good working relationship until Bryant George began pushing for a merger of the FSC and SCDF. Motivated by his hatred for Prejean, George had succeeded in turning Ford executives as well as other funding sources against the FSC and convinced McKnight that he should take overall leadership over the cooperatives. “What is the real purpose for Bryant George and Ford Foundation creating all of this disharmony between McKnight and Charles Prejean?” Black wondered. In a letter to George informing him that cooperative leaders had rejected the idea of a merger but were drawing up plans for closer coordination between their organizations, Prejean stated that they all knew this was unacceptable to Ford but they could not allow outsiders to control the course of the cooperative movement. The FSC had tried to demonstrate that even though rural black southerners might be poor and uneducated, they could develop solutions to complex problems if granted the right resources. The Ford Foundation was apparently unconvinced that poor people could successfully guide their own economic advancement despite evidence the FSC had provided to the contrary. “Send your consultants down, Bryant,” Prejean urged, “and let them reinforce your opinion of us, if that is what you need to support your final argument against us.”39

On 15 June 1972 Mitchell Sviridoff informed Prejean that Ford could no longer continue its support for the FSC because of a “basic, conscientious disagreement on policy.” The FSC wanted to serve all 110 of its member cooperatives despite the strain this placed on resources and the massive amounts of money required, while the Ford Foundation preferred to concentrate its funds on a small number of cooperatives to serve as models for rural development. Foundation executives had decided their best course was to “assist organizations whose goals are more in line with the scale of operation that it is possible for us to undertake.” Sviridoff offered the FSC $90,000 for July and August to help it adjust to the loss of Ford Foundation funds and added, “Our negative decision was not based on a feeling that the program of Federation of Southern Cooperatives lacks merit; clearly, the Federation of Southern Cooperatives is an important force in the lives of the thousands of individuals in the Coops it serves.”40

Reflecting on Ford’s decision some decades later, Prejean acknowledged some fundamental differences in the way the foundation and the FSC viewed social problems. Not entirely convinced that cooperatives were viable and working with limited funds, Ford executives seemed overwhelmed by the scale of the problem and feared a future where the FSC just kept returning and asking them for money. Therefore, they asked the FSC to limit its assistance to the most successful co-ops and essentially abandon the rest. For the FSC’s members, Ford’s approach was out of the question. “I just couldn’t see how they had the right to tell people to scale down their needs,” Prejean stated. Moreover, it would be difficult to develop objective criteria to determine which co-ops to help, and doing so would only divide the movement. As Prejean explained, “We had not come into the organization in that way. Everybody had legitimate needs and everybody’s efforts would be supported and fought for.”41

The FSC’s determination to pursue its own rural development agenda rather than adjusting its programs to fit the wishes of its two biggest financial supporters cost the organization millions of dollars in funding. Internal discord over the SCDF’s decision to cooperate with the OEO study further weakened the cooperative movement. Yet participants refused to allow the movement to die. The FSC survived the next two years by cutting back operations and seeking smaller grants from other foundations and government agencies as well as church groups to enable it to continue to provide a basic level of service to its members.42 A grant from HEW allowed the staff in Alabama to work with local people on plans to create a Black Belt Community Health Center modeled on the TDHC in Mississippi, and the DOL provided funds to train 490 people in the technical, administrative, and business skills they needed to improve the management of their cooperatives. In 1973 the FSC secured a contract from the OMBE to provide technical assistance and loan packaging services to small business entrepreneurs in seven states. Staff of its business development offices (BDOs) located in rural towns such as Tallulah, Louisiana, helped secure 114 loans totaling $10 million as well as 50 procurement contracts worth $1,741,017 in the first year of the program. The FSC also initiated two projects aimed at generating income and decreasing its dependence on outside funds. PanSco, Inc. was chartered as a for-profit subsidiary that began by operating a gift shop and laundromat at the RTRC in Epes and investigating other potential business ventures that could produce revenue for the organization. The FSC’s Forty Acres and a Mule Fund had a similar purpose, aiming to solicit donations for an investment fund. Thus, although money remained tight, the FSC managed to maintain its core services to cooperatives and branched into new areas. In March 1974 Charles Prejean reported that despite the difficulties created by the funding situation, the federation remained “steadfast in our determination to make the rural South a place for Blacks to live and earn a decent livelihood.”43

The FSC continued to act as a leading advocate for rural poor southerners in the second half of the 1970s, often blending its economic and social development programs with political activism. The struggle to ensure that African Americans and other nonwhite residents received their fair share of the jobs and business opportunities created by the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway (TTW) project was an example of this approach. Originally proposed by a group of congressmen from the Tombigbee Valley in the 1940s, construction of the 234-mile waterway was delayed for several decades amid concerns about its cost effectiveness.44 In the 1960s the War on Poverty provided additional leverage to supporters of the project, who emphasized its potential to revitalize the economically depressed counties that lined its planned route from Mississippi’s northern border with Tennessee to the Warrior-Tombigbee Waterway in western Alabama. In 1967 the conservative business leaders who made up the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway Development Authority (TTWDA) appropriated the arguments of social justice activists in their appeal for federal funds. “Sociologists have long recognized that a deprived people can be assisted more effectively in their home environment than by uprooting them,” they stated. The TTW would create jobs and other economic opportunities for the region’s impoverished inhabitants and encourage them to stay in the area instead of migrating to cities that could not absorb them. “Considering the amount of money spent yearly in the Tennessee-Tombigbee region on welfare funds and economic assistance,” the TTWDA concluded, “the question must be posed: Is NOT building the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway actually a SAVINGS?” Congress provided $500,000 for planning and design of the project, and construction began in 1972.45

Despite its expressed concern for the plight of rural poor people, the TTWDA showed little interest in including them as participants or beneficiaries of the project. The first construction contract, for building a dam at Gainesville, Alabama, went to an Oklahoma company that brought in workers from outside the region instead of hiring local people. In November 1973 John Zippert and several other activists staged a demonstration at the dam site to demand equal opportunity for nonwhite workers and more hiring of people from the Gainesville area. In response, company executives invited them to help recruit local people for training and jobs on the project. The FSC agreed to develop a plan to help meet the company’s labor needs and began a major outreach effort in the communities along the TTW to educate people about the project and the opportunities that were available.46

In January 1974 the FSC hosted the first People’s Conference on the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway at its training center in Epes. Lamond Godwin told the gathering of more than 200 community leaders from Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee: “We have had successful struggles against slavery, for civil rights, for political power; now the struggle is for economic development.” He noted that the TTWDA had no African Americans among its thirty-one members or its staff and warned that continued racial discrimination was likely unless black people took action. Conference participants also learned that in addition to the exclusion of nonwhite workers from jobs on the project, government officials were using eminent domain to purchase property from black landowners at less than market value. They voted to create the Minority Peoples Council on the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway Project (MPC), chaired by the FSC’s Wendell Paris, to monitor developments on the waterway and ensure that local people’s voices were heard. The MPC’s goals included the employment of nonwhite workers in all phases of the project, representation on planning boards, minority business development and ownership along the waterway, assistance to black farmers to help them retain and develop their land, and raising citizen awareness of the project and its impact.47

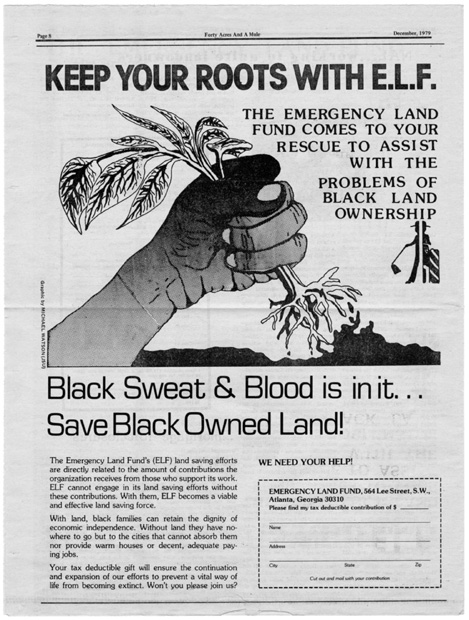

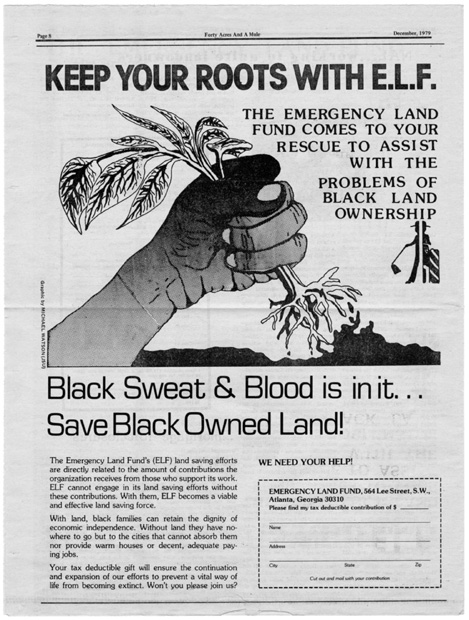

Staff of the Emergency Land Fund (ELF), an organization formed in 1971 to help black farmers remain on the land, worked closely with FSC leaders in the MPC coalition. Founded by black economist and social justice activist Robert Browne, ELF raised hundreds of thousands of dollars from churches and private donors to save black-owned farms that were threatened by tax sales. The group’s assistance bought time for owners to pay their taxes and prevented the loss of 1,498 acres in the first year of the program. Staff members also worked to combat what one of them called “chicanery bordering on the illegal” that frequently transferred black land into the hands of unscrupulous lenders and speculators. Recognizing that economic development and rising land values along the waterway were likely to intensify these problems, ELF developed a list of black landowners in the affected counties and offered legal assistance to help them resist pressures to sell property to the government or private developers.48

In the two years following its initial meeting, the MPC published and distributed an informational pamphlet titled “The People’s Guide to the TTW,” sponsored a workshop for black contractors interested in gaining work on the waterway, pressured the TTWDA to include black representatives on decision-making bodies related to the project, lobbied to increase nonwhite employment on waterway construction, and secured cooperation from the International Union of Operating Engineers for a program to recruit, train, and place black workers in TTW jobs. The FSC’s RTRC provided the venue for training approximately 3,000 people in skilled trades that included carpentry, masonry, and heavy equipment maintenance to prepare them for employment on the project. Like its cooperative development efforts, the federation’s TTW initiatives opened up economic opportunities that encouraged African Americans to stay in the region and, in some cases, lured migrants back to the South. James E. James, a twenty-one-year-old Alabamian who had moved to Boston in the late 1960s, decided to return after hearing about the FSC’s training program. “I was a janitor at the South Boston Army Base, and shortly after I came home for a visit, I heard about the Epes training center,” he told Ebony magazine. “The opportunity to learn a trade and to join the union caused me to move back home.”49

Fund-raising advertisement from an Emergency Land Fund newsletter encouraging African Americans to retain ownership of their farms. 40 Acres and a Mule, December 1979, p. 8. David R. Bowen Collection, Congressional and Political Research Center, Mississippi State University Libraries.

The MPC also took action to ensure that black workers were employed on the TTW once they were trained. Hiring policies in the initial phases of waterway construction were guided by a federal affirmative action plan that aimed for 20 percent minority participation in a region where African Americans were 40 percent of the population. The MPC developed an alternative proposal that aimed for 40 percent minority hiring by 1977 and secured support for the plan from unions, contractors, and community groups.50 Federal agencies were reluctant to endorse the plan, but continued pressure from MPC activists eventually led the DOL’s Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs to impose a new TTW project plan on contractors that extended to both federal and nonfederal construction projects in thirty counties in Alabama and Mississippi. Described by Lamond Godwin as “the most inclusive area-wide affirmative action plan ever issued” by a government agency, the measure called for 19 percent employment of nonwhite workers immediately in all thirty counties, to be increased to 30 percent by 1980.51 Although this goal was never fully achieved, in 1983 contractors reported an overall minority employment rate ranging from 23 to 27 percent during the past five years of construction. An article in Mainstream Mississippi noted, “A number of unprecedented programs and activities undertaken on the Tenn-Tom project have ensured that local people, particularly the disadvantaged, do benefit to the maximum extent possible from the job and business opportunities from the waterway construction.” One observer attributed this largely to the FSC and its allies, calling the federation “the single most important voice and advocate for minorities on the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway.” Two years later, after completion of the waterway, the MPC’s contribution to ensuring broad participation was recognized at a dedication ceremony in Columbus.52

The effort to secure a place for rural poor people in the TTW led the FSC to widen the scope of its activities beyond support for cooperatives. Activists understood the importance of nonfarm employment opportunities to the rural economy, and in the second half of the 1970s the FSC supplemented earlier programs aimed at helping black farmers stay on the land with training programs designed to enable people to make the transition to jobs on the TTW and other industries outside agriculture. In 1975 the FSC applied for CETA funds to operate an outreach, referral, and work experience program and to develop a resource team to craft a long-range training and employment strategy for the TTW region. Federal officials rejected the proposal, but the FSC secured support from other organizations to proceed with parts of the project. The FSC worked with a local union to create an eight-month-long training program for fifty heavy equipment operators, and two-thirds of the trainees went on to find jobs on the TTW. Foundation grants funded the research portion of the plan, which identified other skills in which workers could be trained and employed locally. As Charles Prejean noted, such work was essential to fulfilling the promise to reduce poverty, unemployment, and out-migration from the TTW impact area, which had been highlighted by its supporters when they were lobbying for federal appropriations. “We have yet to see or feel these ‘re-development benefits’ claimed for the project,” he wrote in 1976. “This is mainly because the emphasis thus far has been on the physical development of the project and not the human resource development and training needed to involve indigenous, disadvantaged and minority people in the TTW.”53

Despite the need to do more, the political conservatism and economic austerity of the 1970s were not conducive to expansion or initiation of new projects, and the FSC had problems just continuing some of its existing programs. The success of the business development efforts supported by the OMBE was jeopardized when federal officials ordered the program to decentralize in 1974, forcing each of the FSC’s BDOs to seek refunding from regional offices of the federal agency. The FSC’s business packager Ramon Tyson detected an urban bias in regional administrators’ plans to close the BDO in Tallulah, Louisiana, and open one in Monroe (population 80,000) instead. Black businesses and cooperatives in Madison Parish and seven other rural parishes served by the Tallulah BDO lost a valuable resource as a result of the decision.54

In April 1975 the OMBE terminated its contract with the FSC and announced plans to fund state OMBE offices in Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia instead. Seven of the eleven BDOs the FSC had administered received funding from the regional office in Atlanta, but the others were unable to continue operations. The diversion of funds from nonprofit organizations like the FSC to state offices controlled by southern governors worried Prejean and other activists. State officials’ past history of neglect of rural poor people hardly inspired confidence, and recent studies of the ways administrators in Mississippi and Alabama chose to spend federal money showed that economic development efforts were concentrated in areas with predominantly white populations. “We are concerned with what may be an overall trend in OMBE to consign and direct precious flexible Federal resources to state governments who have historically shown little interest in the problems and need for development of business enterprises within the Black community,” Prejean wrote in a letter to Congressman Parren Mitchell.55

The experience with the OMBE typified the FSC’s relationship with the federal government during the Nixon and Ford administrations. Funding was scant and uncertain, bureaucratic rules and restrictions limited the effectiveness of the few programs that were funded, and agency officials expressed little interest in supporting the cooperative movement.56 The election of Democratic president Jimmy Carter in 1976 was a welcome change, and the FSC’s prospects brightened a little with the appointment of several long-time friends to key positions. Secretary of Labor Ray Marshall was the son of a tenant farmer and a southern liberal who understood the root causes of rural poverty, including the role that racism played in the problem. Like FSC leaders, Marshall believed cooperatives could provide poor people with the economic independence they needed to mobilize politically and transform power relationships in the South. Additionally, new leadership at the FmHA resulted in policies that aimed to improve services to rural poor people, increase the proportion of loan funds granted to African Americans, and foster better cooperation with nonprofit groups such as the FSC.57

Another promising development came when administration officials successfully pushed for passage of the National Consumer Cooperative Bank Act, which aimed to support consumer cooperatives and included provisions to create a self-help development fund for low-income cooperatives. Speaking in favor of the legislation before a Senate subcommittee in January 1978, Assistant Treasury Secretary Robert C. Altman stated, “Consumer cooperatives in blighted urban and underdeveloped rural areas may offer one of the best prospects for economic development or redevelopment there.” The new bank was eventually capitalized with $300 million for loans to cooperatives, and another $75 million was allocated to the Office of Self-Help and Technical Assistance to serve low-income cooperatives. In his 1980 budget, President Carter requested $12 million to invest in community development credit unions.58

The FSC benefited directly from federal agencies’ renewed willingness to fund its rural development efforts during the Carter years. In 1977 the CSA provided assistance to the FSC for the first time since the fight over the OEO evaluation in 1972, partially funding an energy conservation and renewable energy conversion program for small farmers. Even before the energy crisis of the 1970s, FSC staff had perceived the potential economic and environmental benefits of encouraging farmers to reduce their consumption of expensive fossil fuels. The CSA grant enabled them to develop demonstration projects, such as solar greenhouses, windmills, and alternative crop production methods, and to teach members how to switch from traditional to energy-conserving farming methods. The DOL provided $172,585 in CETA funds for a housing rehabilitation program operated by the FSC in cooperation with local governments in Greene County and the towns of Forkland and Boligee in Alabama. The funds were used to employ a project director and two housing construction crews, each comprising a building supervisor, loan packager, and five CETA trainees. Together the two groups worked to repair sixty substandard homes inhabited by farmworkers and other rural poor people. The FSC was also approved as a national sponsor for the Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA) program, enabling it to recruit one hundred local volunteers from among its member groups as well as ten national volunteers to be based in the southeastern states. By August 1978 the FSC had managed to secure close to $2 million in support of its programs from the federal government.59

Although conditions imposed by both federal and foundation grants prohibited the FSC from directly engaging in political activities, its goal of economic empowerment for black southerners was inextricably linked to that of political empowerment. Cooperative businesses provided alternatives to migration and encouraged African Americans to stay in the South, helping maintain black voting majorities in the plantation counties. Moreover, cooperative organizing fostered political organizing in the communities where the FSC was active and helped black candidates win local elections. As Ezra Cunningham explained, cooperatives were a central element in the post-1960s freedom movement. “We accomplished the fact that [black people] stayed,” he stated. “Then we also accomplished the other fact that we did some things politically and civically. . . . I really think that SWAFCA had more to do with the political advancement than the Alabama Democratic Conference, the Alabama New South Coalition, and all of these other things.”60

These connections were also evident in Tallulah, Louisiana. The FSC helped set up a credit union there in October 1969, providing money to hire a bookkeeper and two field-workers to train members. The credit union in turn contributed to the success of a newly established cooperative store, with many credit union members buying shares in the store. According to the FSC, the credit union and cooperative were part of a “general awakening by Black people to control the political and economic destiny of their own communities. A number of Blacks have been elected to public office in Tallulah as part of the same movement which promoted the growth of the credit union and consumer store.” In July 1974 the local governments of Tallulah and two other communities served by the FSC (Waterproof and Lake Providence) came under black control for the first time. Tallulah mayor Adell Williams credited the FSC’s BDO staff in Louisiana with boosting black business development in the region, participating in community events and organizations, and encouraging town officials to form a local development corporation to initiate new projects. With assistance from the FSC and government agencies, he stated, “we will meet the task in front of us of making Tallulah a better place to live for all its citizens.”61

The FSC’s presence and the new forms of activism it generated worried conservative southerners who feared the consequences of black political power. From the beginning, the FSC had endured constant criticism and attacks aimed at weakening or destroying the organization. Of the eleven states included in its initial OEO grant in 1968, only Georgia gave immediate and unconditional approval for the FSC to operate there. The governors of Alabama, Arkansas, Missouri, and Tennessee vetoed the grant, and officials in Louisiana and South Carolina imposed restrictions that forced FSC staff to gain approval from their SEOOs before initiating projects. The remaining four states neither approved nor vetoed the grant, allowing it to go into effect after the thirty-day veto period expired.62

The hostility of state and local officials toward the organization often hindered the FSC’s work. The DOL’s southeast regional office delayed approval of an FSC management training grant for two years despite federal officials’ support for the project. To Charles Prejean, the reasons for the delay were obvious: “We are primarily a Black organization trying to deal with problems of the poor. To fund us would mean an admission of neglect to the Black and poor of the Southeast region.”63 After asking the FSC to rewrite and resubmit its proposal four times, late in 1971 the DOL finally accepted a version that was essentially the same as the original proposal. “We honestly believe that they did this to discourage us,” Prejean stated.64

Similar obstructionism plagued the PLBA’s attempts to build homes for its members on the tract of land it shared with the FSC in Sumter County, delaying completion of the project for a decade. The PLBA filed its initial application for a rural cooperative housing loan from the FmHA in November 1971. After battling multiple obstacles that included the skepticism of local and state FmHA officials, an eight-month moratorium on low-income housing loans imposed by President Nixon in 1973, the Alabama Water Improvement Commission’s “arbitrary and capricious” refusal to approve the proposed water and sewage system for the site, prolonged negotiations with the Sumter County water authority to include the project in new water services planned for rural residents, and a last-minute investigation by the USDA’s Office of the Inspector General just as final approval from the FmHA was pending in November 1979, forty families finally moved into newly constructed homes and rental units at the PLBA’s Wendy Hills subdivision early in 1981.65

The strongest opposition to the FSC came from white leaders in Alabama, home to the RTRC and the largest concentration of federation staff. Many of the people who occupied the trailer homes and dormitories at the Epes site were veterans of the civil rights movement. Although they were not allowed to use their work time or resources for political activities, Charles Prejean admitted that FSC staff had “a strong identity with, and continue to support activities in, the areas of racial equality and social justice.” White residents of Sumter County thus noticed a marked increase in black voter registration, candidates running for office, and the general level of assertiveness shown by African Americans in their community in the 1970s. Many of them found the changes difficult to accept. The transition to an all-black government in neighboring Greene County was an example of the threat posed to elite white families accustomed to dominating the political and economic structures of the Black Belt. Livingston Home Record editor John Neel asserted: “Nobody wants what happened in Greene County to happen here.” Yet opponents of black political empowerment proved unable to stop it. African Americans voted in large numbers in the 1976 elections, and white incumbents only narrowly defeated their black challengers. In 1978 black candidates won two seats on the five-member board of education.66

White political leaders in Sumter County were convinced that the source of all their problems was the FSC. Rumors of corruption, nepotism, mismanagement, and the training of armed black revolutionaries at the RTRC circulated among local residents, and the Home Record denounced “government-funded activism.” In May 1979 more than one hundred white people met at the Cotton Patch restaurant in Greene County to discuss the situation. The group included John Neel, I. Drayton Pruitt (a lawyer who had tried to block the sale of land to the PLBA), local officials Sam Massengill and Joe Steagall, state legislator Preston Minus, Congressman Richard Shelby, and staff representatives of Alabama senators Howell Heflin and Donald Stewart. Participants shared stories they had heard about the misuse of federal funds and other illegal activities at the RTRC and agreed that the FSC should be investigated. Pruitt, Massengill, and Steagall then sent a formal letter of complaint to Shelby, who forwarded it to the GAO. The GAO reported in September that its preliminary inquiries had uncovered nothing to suggest that an investigation was warranted, pointing out that the inspectors general of the federal agencies that funded FSC activities could investigate further if they wanted to. John Zippert explained to supporters who asked for information about the GAO inquiry that the FSC had done nothing wrong and that the complaint was a response to a recent school boycott and other activities by local black people aimed at improving conditions in the public schools. Although some federation staff participated in these activities, they did so on their own time and no FSC funds were used. “Basically, we feel this investigation has been motivated as a harassment tactic by local racist Alabama officials against FSC,” he stated. “We consider this investigation merely another of many occupational hazards for organizations genuinely committed to assisting poor people in a process of community change and development in America.”67

The GAO probe did not satisfy the FSC’s opponents, and more “occupational hazards” followed. J. R. Brooks, the United States attorney for Alabama’s Northern District, convened a grand jury to further investigate the FSC. On 31 December 1979 FBI agents acting on behalf of the jury served Charles Prejean with a subpoena demanding that he turn over “any and all documents in connection with federal funding of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives and its affiliated cooperatives” for the period from 1976 to 1979. The agents refused to provide information regarding specific allegations against the FSC or its employees, and the organization’s legal counsel advised Prejean not to comply until the FBI explained the reason for the request. As one Mississippi lawyer who had worked with the FSC for several years noted, the government’s subpoena was unusually sweeping. “It reflects a ‘witch hunt,’ ” he wrote in a letter to his senator. “No one has been identified as a target, the nature of any alleged wrong-doing is unknown, and the requested information is so broad that every transaction must be under investigation.”68 Prejean explained that the FSC was willing to cooperate with inquiries into specific individuals or activities, but not with what seemed to be “a deliberate attempt on the part of the F. B. I. and the U. S. Attorney’s office to debilitate and destroy the entire organization, without giving any reason or basis for their action.” He pointed out that the recent GAO audit had found no misuse of federal funds, suggesting that political motivations rather than legitimate concerns lay behind the grand jury investigation.69