Take money out of your account?

Take money out of your account?I had a friend in college named Chip. Ever since I knew Chip, he was perpetually disorganized. Shortly after we graduated, he called me one day and informed me he was coming to visit me in Florida (he lived in Pennsylvania). I assumed he would call me back to set a date or get directions or make some kind of plan for his visit.

Five days later, Chip showed up at my front door.

“How did you get here?” I asked half bemused, half perplexed.

“I drove.”

“Did you have a map?” I probed.

“No.” he responded.

“Then how did you find my house?”

“I kept stopping and asking directions.” he replied quite matter-of-factly.

“To Florida?” I asked incredulously.

“Yes.”

As it turned out, Chip had driven over 1,000 miles, eventually locating my house, using only a vague sense of direction and a shamelessly outgoing personality. It had taken him five days and several wrong turns, but he eventually made it.

Chip knew how to drive and how to read road signs, but he did not have a plan as to where he was going or how he was going to get there. Believe it or not, some investors trade this way. Unfortunately, most are not as lucky as Chip. It is very difficult to get where you are going if you do not have a plan for getting there.

This is why constructing a plan for your option selling portfolio is so important. In this book, you’ve learned why, how, when, and where to sell options. You have the eggs, flour, sugar, and mixer. But you still have to combine the ingredients correctly and cook at the right temperature to get a cake.

That is what this chapter is about.

Steps 1–3 involve establishing a trading plan for your portfolio—a theme we allude to several times in this book. The remaining steps involve how to structure your portfolio and position for maximum gains and minimal risk. These steps pull together many of the trading concepts we have covered.

While we certainly do not recommend trading like Chip, we also think it important to not “over plan” your option selling portfolio. Option selling, especially on fundamentals, requires a certain degree of flexibility that you cannot write into a computerized trading plan. I know the number crunchers out there are already wrinkling their noses because we are not going to give them a formula to plug into their spreadsheets and “run the numbers” for the next three weeks. However, “paralysis by analysis” is just as big a threat as under planning, in our opinion. It is important to have a general trading plan. But give yourself some leeway to make informed trading decisions and adjustments along the way.

Constructing an effective option selling portfolio starts out like any self-help book you’ve ever read. You must have a goal. You must have an objective. “I want to make money” is not specific enough.

“I want to make 40% annualized returns after fees” is specific.

“I want to generate X amount of quarterly income” is specific.

“I want to diversify my overall investment holdings into a new asset class” is specific.

Your first step in constructing your portfolio is to decide why you are starting the portfolio and what you hope to accomplish. It sounds simple enough and yet many investors fail to define this from the beginning, which can result in an unfocused trading plan and inconsistent results. Knowing your objectives from the beginning will help you to better define, build, and if necessary, adjust your trading plan.

This is the very first step we take with any client of our firm and it is the first step you should take as well. Even if you are hiring a professional trader to manage your account on your behalf, you must first set your objectives before any trading plan is constructed.

Again, it sounds simple. But most investors take the Chip approach and decide as they go. Knowing where you are going means making more focused decisions. It is your money. You can’t afford to be unfocused! What will you do if, and when, you meet your objective?

Take money out of your account?

Take money out of your account?

Add money to your account?

Add money to your account?

Stop trading?

Stop trading?

Continue with your program with an objective of building on gains? (Better set a new objective.)

Continue with your program with an objective of building on gains? (Better set a new objective.)

Hitting an objective is gratifying and often a good time to re-evaluate your game plan. However, it helps to have a general idea of what you will do when you reach your portfolio goal.

It is true that there is no such thing as a free lunch. If you want to attain 30, 40, 50% returns or more, you are going to have to be willing to put some funds at risk. You can’t expect to make 40% on your money taking T-Bill risk. I cannot count the number of investors that have called me over the years and asked “what would my maximum drawdown be?”

We’re all adults here. If you want the short, blunt answer, your maximum drawdown is 100% of your equity and then some. If you ask for a “worse case scenario” then that is it. Just like if you buy a stock and the company goes belly up, you lose your investment. That’s a worse case scenario. That is what is technically possible.

However, if you want a more realistic answer, one would have to do something terribly, terribly wrong to ever end up in this predicament. Like watching your grossly undiversified, over-positioned portfolio move sharply against you day after day without doing anything about it. Unlimited risk simply means that you have to manage your risk yourself. The market is not going to do it for you. If you buy an option, the structure of the market allows you to rest assured that you have a finite risk. The trade-off is that the odds are high your option will expire worthless and as a buyer, you will lose.

In selling options, you get high odds of success in your favor. The trade-off is you have to take steps to manage your own risk.

And as we learned in Chapter 9, there are plenty of effective ways for doing this. Step 3 of structuring your portfolio is to know which of these methods you intend to utilize in your trading plan and how much of your capital you are willing to risk to achieve your objectives.

As we tell investors when helping them build their trading plan, your success as an option seller will have not so much to do with the 80% or so of options that expire worthless. It will have more to do with how you handle the 10–20% that do not.

Chapter 9 discusses strategies for managing risk on individual trades. But one must also consider the risk approach to the portfolio as a whole. Below are the questions you may want to answer for yourself in how you want the risk managed in your own account.

1. Do I want to spread or write naked? Naked selling can offer faster profits and early exits. Spreads can offer limited exposure but longer time frames for profit realization. We typically recommend a combination of both. However, you must select strategies that not only match the market’s temperament, but your own.

2. How much of my portfolio funds do I want to keep as “reserves?” No matter how many markets or trades you have on at any given time, you want to keep a certain portion of your trading account in liquid reserves. As you learned earlier, margin requirements for short options can fluctuate on a daily basis, depending on market movement and volatility. Keeping a healthy portion of the account in cash reserve makes for a more stabile portfolio. You can devise your own comfort level for the amount of cash you choose to keep in reserve. This subject is discussed in greater detail later in this chapter.

3. Think through how you will handle losses and if you have a “drop dead” point at which you will cease trading and modify your trading plan. Moderate, periodic losses are to be expected and are part of any normal trading program. If kept manageable in an option selling program, they can generally be made up with your other trades as long as you are diversified properly. However, if you experience a substantial loss over a given time period, you should have a predetermined figure in mind as to at what point you cease trading and re-evaluate. Trading, even selling options, when you are rattled or frustrated is not a good idea. Set a drop dead point of what you would be “uncomfortable” losing. If your account hits that point, close your positions and take a week or two off. Coming back and making adjustments is much easier with a clear head.

There is no answer as to “what type of drawdowns can I expect?” I have seen traders have a 10–20% drawdown and freakout. I have seen traders start out on top and never have a drawdown (against invested capital).

In general, if you are selling futures options, you are targeting 20–50% returns. Therefore, to stay in the game, you should realize that drawdowns of 10–20% or more are not out of the question and that you should be comfortable with this type of movement on the funds you have invested. Realize that this is the normal ebb and flow of futures options and that drawdowns of this nature, while unpleasant, can also be recovered somewhat quickly with this type of strategy.

Once you have established your initial trading strategy and risk parameters, it is time to begin establishing positions. It’s time to start selling options!

One concept we have repeatedly discussed is to only sell options with the most clear-cut fundamental advantages. However, a cornerstone to a successful portfolio is diversification.

Will you be able to fully diversify your portfolio when you first begin selling options? Well, you could, but we would advise against it. You will look to sell options only in markets offering a distinct fundamental advantage. This will obviously not be all markets at all times.

At the same time, you will want to build towards diversifying your option sales across several different sectors. A portfolio built on selling S&P options is not diversified. I have talked to many traders who based whole portfolios on selling S&P strangles. These portfolios can do well for a while, until a big move comes along. It is during these moves that S&P-only traders tend to discover the value of diversifying.

One of the benefits of trading commodities options is that one can sell options across a widely diversified spectrum of physical products. As we illustrated earlier, one can sell a variety of stock options across several equity sectors, yet if the stock market as a whole moves up or down, all stocks tend to follow suit. In commodities, except in special circumstances, this is generally not the case. Therefore, one may be short sugar calls and short heating oil puts and be right on both.

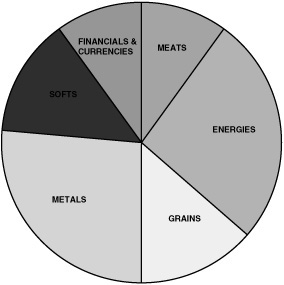

Figure 15.1. illustrates how a sample portfolio might look for a typical well diversified account.

Please note that this is only an example and the face of this pie chart would be constantly changing in a real live portfolio. Notice that some markets are short only calls, some only puts, and some are short both calls and puts (strangled). This reflects the trader’s fundamental views of the underlying markets—bearish, bullish or decidedly neutral. Strangles are typically written in markets where the trader is not overly bullish or bearish but volatility has surged to levels where simply selling distant options on both sides of the market looks like a high probability play. Note also that when a category denotes short puts or calls in a certain market, these could be naked or covered positions.

FIGURE 15.1 Pie Graph Showing Sample Portfolio Diversification

Keeping your portfolio diversified carries obvious benefits. The typical knock on option selling is that one losing trade can wipe out months of gains. (It would not be surprising to learn that this “drawback” probably derived from non-diversified S&P traders.) Lets face it, trades can go bad, markets can make erratic, illogical moves. You can lose money selling options. If a trade goes bad, and it is your only trade, and you have 50% of your portfolio in this trade, chances are that you are going to take it on the chin, even if you utilize proper risk management techniques.

If you are diversified over five or six different markets, and one goes bad, it is a small percentage of your overall portfolio. You take the loss, you move on. You make it up somewhere else.

Probably the most difficult challenge we face as portfolio managers is not the trading. It is getting option traders or even neophyte option sellers to think about this as an investment, and not trading. You manage the portfolio like a portfolio and not a trading account.

You plant your garden and then let it grow. Occasionally, you pick the fruit and or pull up dead plants and replace them. You do not throw seeds every which way and see what pops up. Nor do you plant all one crop and risk a blight destroying your entire garden. You don’t “load up” on something just because it looks good. You have to think of each trade as to how it fits in and balances the entire portfolio. For instance, if you are already short crude oil and heating oil puts and you see an opportunity to sell unleaded gasoline puts, you could be risking overloading your portfolio in a single sector. This is true even if selling unleaded gas puts looks like an excellent trade.

This does not mean that you have to equally balance your portfolio across all sectors. You or your portfolio manager may like some markets better than others or feel there is less risk in some trades than others. There is no crime in overweighting certain markets at certain times. Which brings us to our next step.

Effective margin management is crucial to your success as an option seller. Again, as we state several times in this book, over positioning, not miscalling the markets, is probably the number one reason traders lose money selling options. In a futures options account, your “available margin” is simply your cash balance. This is the amount of cash you have available in your account that is not being used to hold open option positions.

However, what some new option sellers overlook is the fact that margin requirements for positions can, and most do, change—in fact, they do on a daily basis. SPAN margins for each position are recalculated and marked to the market at the end of each day. Most of the time, these changes will be nominal. If the option is decaying, the margin requirement to hold the position will change and your available margin (also known as excess equity) will rise. Consequently, if a position is moving against you (or even if volatility is simply increasing), the margin requirement to hold that position can increase. This means that you will want to have excess cash in reserve to account for such changes in margin. Every position is not going to immediately race to zero and expire worthless. In fact, many of your short option positions may initially increase in value. This is normal. Remember, one reason we sell options is so that we don’t have to time the market (although we can always try). We sell options to give the market plenty of room to move around. We don’t try to pick market tops and bottoms. Long-term fundamentals can be accurate in assessing longer term price projections. But if you sell your option in this market, the chances are 50–50 that the underlying is going to move against you the following day. This doesn’t necessarily mean the option value will move against you. But it can.

For instance, if you sell a call on day one and day two the underlying price of the market goes up. Chances are your option value, and thus your margin requirement for that position, may increase. Most of the time, if you are selling far out-of-the-money options, these increases will be nominal and benign—especially if time value is running out on the option. But you nonetheless want to have excess margin available in your account to cover these margin fluctuations.

For a moderate to conservative account, this typically means holding at least 30–40% of your total portfolio in cash. If you sell all naked options, you may want to hold slightly more. However, this type of cash cushion should be more than adequate to handle most market fluctuations if you are properly diversified.

New option traders tend to live in fear of the margin call. As we discussed earlier, margin calls are nothing to fear. It simply means you either have to close a position or increase your equity stake if you wish to hold your position. If you are getting a margin call, chances are you should probably be closing something.

However, if you are following these cash management rules, the chances of you ever receiving a margin call in an option selling account are remote.

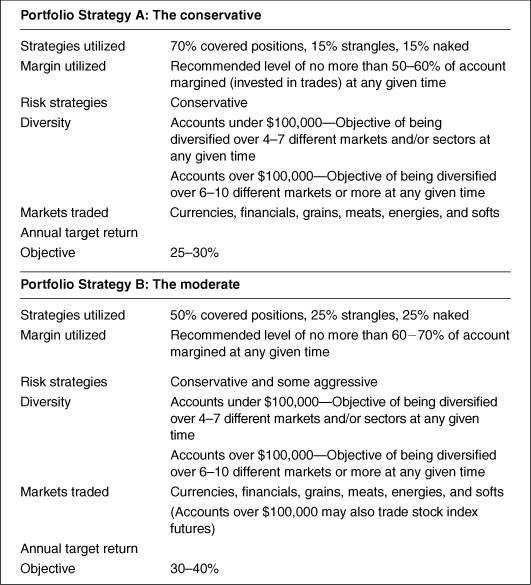

Table 15.1 illustrates a suggested portfolio structure for new option selling accounts. These are presented for example purposes only and no representation is made that this structure will be successful for all accounts at all times. However, we tend to base our managed portfolios on these models and have found them to be effective over the years. Perhaps you will as well.

TABLE 15.1 Recommended Portfolio Management Strategies

*These are target objectives only. A trader or account manager may make every effort to attain and hold these levels but circumstances beyond his control such as sudden market moves or lack of perceived trading opportunities could cause an account to move above or below these levels.

These figures are guidelines only and can be adjusted to meet the preferences of the individual investor. The strategies are examples of a conservative, moderate and aggressive portfolio. The following outlines may help in deciding which is right for you.

Overpositioning usually results from over trading. Over trading usually results from overzealous traders ready to pull the trigger on whatever the flavor of the day may be. Remember, this is an investment, not an “activity.” This is meant to be slow and steady. Many of our managed portfolios may only trade 2–4 times per month. You execute a trade only when everything appears to be in your favor. Your fundamentals, your strike, your premium, your market. Work towards diversifying your portfolio but do not feel that you must immediately distribute your capital into seven different sectors. Wait for your opportunities, pick your points.

Like any other type of investing, a successful option selling portfolio starts with a good trading plan. An investor should view his option selling portfolio as an investment, not an “activity.” Decide your main objective for the portfolio and what you are willing to risk to attain it. Your portfolio should be diversified. Fortunately in commodities, true diversification is possible. Keep a healthy portion of your capital as back up equity (in cash). Do not over trade.

There are many “Chips” out there in the investment world. Any one of them would probably be glad to tell you the sob story of their trading gone awry. If you want to make money in the options market, don’t be like Chip. Have a plan.