two

Pine Trees in Myth and Reality

‘Pitys’ was an ancient Greek name for the pine, and also a beautiful nymph. The simple version of her story merely says that Pan, god of the forests, pursued her and in desperation to escape him she changed herself into a pine tree. Another version of the story relates how she was caught in a love triangle with Pan and Boreas, god of the north wind, an angry character: ‘Force is fitting for me. By force . . . I overturn knotted oaks, harden the snow and strike the earth with hail.’1 Pitys preferred Pan, and in his anger Boreas threw her against a cliff. Earth or Pan (stories vary) took pity on her and turned her into a pine tree, her tears becoming the resin which pines still weep from their wounds. Her myth tells poetic truths about pine trees, of associations in the European mind with northernness, forests, endurance and survival through mutability, and adds the detail of the resin that pines and other conifers exude.

Other metamorphosis myths mention the Oreiades, mountain nymphs who were born and died with their native pines, and the maidens of Oikhaliai who, when the princess Dryope had departed to join the nymphs, spread a rumour that she had been abducted. The nymphs were angry and turned the maidens into pine trees.2

What other evidence is there of how Europeans thought about pine trees in the distant past? The vocabulary of the Mediterranean world included both pitys, which referred to pine trees generally as well as the nymph, and peuke. This also referred to pines,3 and gave modern Greek the word for pine tree and also Picea, the genus to which spruces belong. The Latin for pine tree was pinus, giving the generic name for the species. The sound/syllable pi, in pitys and pinus, traced back to an Indo-European base, is also found in pix, Latin for pitch, and the first element of Sanskrit pītudāru, as well as in pissasphalt, a now-archaic English word relating to bitumen (this definition from the Oxford English Dictionary). The pi-element evidently related both to particular trees and to a substance associated with them that was widely known since ancient times. ‘Pitch’, and similar words based on the same root, found its way into numerous medieval and modern European languages.

Pan discovering Pitys being turned into a pine, from an Italian emblem book, 1550s. |

|

Latin pinus gave some southern European languages their word for pine tree: French pin, Italian pignola and Spanish piño. In Old English it was pin, the usage reinforced by the French spoken after the Norman Conquest. It was spelled variously – pin, pyn – before settling down to pine in the fifteenth or sixteenth century, and has remained in common use in English ever since. It was often applied to all evergreen conifers, including ones only distantly related to true pines, and was, confusingly, also used for some trees such as alder, which bear cones but are not conifers.4 In the colonial period, English-speaking settlers in the southern hemisphere used ‘pine’ to name many exotic plants that displayed a generally conical, evergreen habit. Norfolk Island pine (Araucaria heterophylla), Chilean pine (or monkey puzzle tree, Araucaria araucana), Huon pine (Lagarostrobos franklinii) and celery pines (genus Phyllocladus) are just a few examples of plants with such names. Such colloquial use continues, and when a tree new to science was discovered in New South Wales in 1994, it became known as the Wollemi pine (Wollemia nobilis); but none of these trees belongs to genus Pinus.

Exploration and colonization by other nations also left linguistic marks – the French Canadians called a pine tree un pin, the Spanish in Mexico and the adjoining southwestern USA left the word piño, transmuted in American English to pinyon. A colonial legacy of pin and piño also remains in southern-hemisphere names for non-pine conifers.

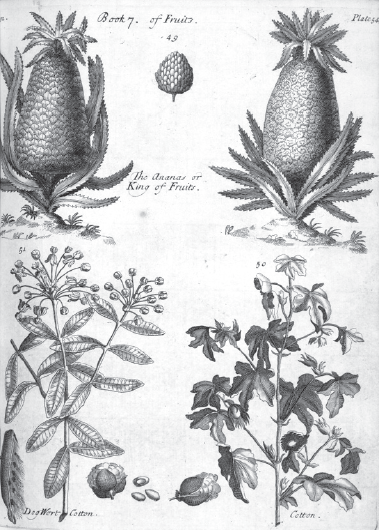

Print made by Crispjin de Passe the Elder after Jacques le Moyne, ‘Pineapple’, c. 1593–1603, engraving. Pine cones were known in various European languages as pine-apples; this branch bears both an open cone and a distinctly pineapple-like closed one, echoing the confusion of early explorers.

One spectacular case of misidentification was made in 1493, when Columbus’s expedition was confronted with a fruit new to it on Guadeloupe. It was large, of a roughly conical shape and with a surface with a spiralling, scale-like pattern in hexagonal shapes, each with a papery spine in the centre. The only thing to which expedition members could relate it from their own knowledge was a pine cone; so they called it piña, brought it back to Europe and presented it to the king. Most European names, and the botanical one, Ananas comosus, are descended from the Brazilian Tupi Indian word, nana or anana (excellent fruit). The English, for once, agreed with the Spanish and called it a pineapple, their general name for pine cones at this period.5

In Britain ‘pine’ has a rival word, ‘fir’, derived from Germanic or Norse languages. As a collective name for conifers, ‘fir’ is sometimes used interchangeably with ‘pine’, especially when describing large numbers of trees viewed from a distance, or their timber. It still has strong currency. In botanical terms it is strictly applied as the English name for trees of the genus Abies, which is closely related to pines. It survives in some Scandinavian languages and as an element of a German word for pine, keifer. Russians, on the other hand, use the word kedr, derived from cedar, for some pine species, although sosna is the general Russian word.6 Spruces take their common English name from an old word for the country of Prussia.

The peoples of pre-modern Europe clearly recognized pines and their relations, and evidently valued pitch, a product associated with them. Their knowledge, in the way a modern botanist would understand it, is less obvious. The Greek scholar Theophrastus (c. 371–287 BC) was one person who did leave a record, in Enquiry into Plants. Unfortunately for those unable to read the work in the original, Sir Arthur Hort, Theophrastus’ translator, was not a botanist.7 He used the word ‘fir’ even when he meant pinus species – ‘fir of Ida’ and ‘fir of the seashore’ (identified as Corsican pine and Aleppo pine respectively).8 Pines cultivated for their edible seed – pine nuts – were also known.

‘The Ananas or King of Fruits’, an illustration to Pierre Pomet’s A Compleat History of Druggs (1737), a pineapple drawn to look like a pine cone.

Theophrastus consulted people with an interest in pines – torch cutters on Mount Ida, shipbuilders and resin tappers. His informants varied in their opinions about the natural history of pine trees, and he said that the Arcadians had decided views about them (even though pine trees were uncommon in Arcadia), and ‘then dispute altogether the nomenclature’.9 Theophrastus was dealing with problems that have exasperated taxonomists to the present day. One is that ‘It is by their use that different characters are recognised’10 – that most people are interested in pine trees (as well as most other plants) for their utility. The other, unrealized until the late nineteenth century, is that even within species, pines can vary widely in form, depending on habitat. Observations were confused by the belief, current at the time, that trees were male and female.

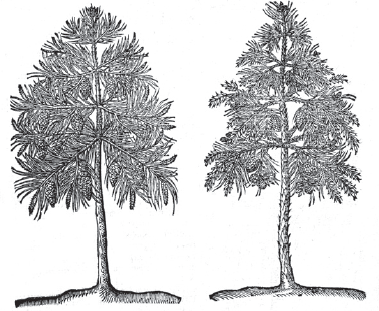

David Kandel, ‘Thannen und Lerchenbeum’, illustration to Hieronymus Bock, Kreuter Büch darin Underschied (1546). |

|

Nicholas Mirov, who studied pine trees in the twentieth century, commented that the names given to pines and related conifers by European scholars of classical literature were often hopelessly confused, but considered that the Greeks made a distinction based on size and bearing, calling scrubby, resinous pines used mostly for pitch pitys, and tall, stately mountain pines peuke. Later, Russell Meiggs, a classicist who had also worked in the timber trade, concluded that the differences Theophrastus described between pitys and peuke were impossible to reconcile, and further confounded by varying usage of names in different areas. He considered that five pine species were significant: Scots pine in Macedonia and around the Black Sea; Aleppo pine; maritime pine, for resin, in Italy and the western Mediterranean; Austrian pine and P. laricio (formerly indicating Corsican pine, now considered Austrian pine); and Italian stone pine for pine nuts.11

Information about the natural history of pines from other classical authors is scant, their observations being mostly incidental or relating to practical uses. Pliny the Elder (ad 23–79) apparently recognized three pine species (translated by Mirov as Swiss stone pine, Scots pine and Italian stone pine) and recorded two words that have persisted in pine-related botanical vocabulary, pinaster and taeda. Pinaster was a wild pine that grew along the coast near Rome. Taeda was a more mysterious term. It literally means torch, and confused early modern botanists for years before the realization that it could apply to any old, diseased or dead conifer with the capacity to flare up if it caught fire.

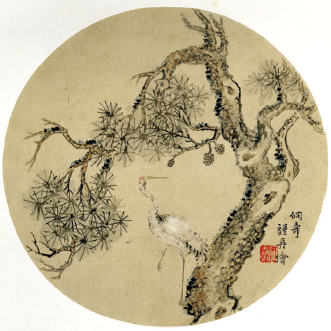

The other area that provides much early evidence for human thought and interaction with pine trees is China. Here, pine trees (which transliterate from Chinese to English as sung or song) have occupied a special position in human consciousness for millennia. They appear to have had some of the associations anciently ascribed to oaks in Europe, especially resistance to the ravages of time,12 and Shouxing, the Chinese god of immortality, is usually shown standing at the foot of a pine tree.

Pines are recorded as trees to be planted on the tumuli of Imperial tombs sometime during the late centuries BC, and the Shan Hai Ching, an ancient compilation of myth and geography about China, frequently observes that they grow at the tops of mountains. The literature includes many references to pines and their products; the Chinese accumulated an enormous practical knowledge of botany, including pine trees in general. Pine trees yielded soot particularly valued for ink; all parts of the tree were regarded as useful against pests, and there was evidently much knowledge relating to the planting and cultivation of pines.13 From about the twelfth century ad onwards, Chinese scholars observed and recorded that the number of needles per fascicle varied and could be categorized, well before Europeans had noted this and established it as an aid to identification, but the sources conflict over numbers of needle per bundle and are difficult to reconcile with species observable in modern China.

Fresco of a pine tree, c. 30 BC, from the Villa of Livia, Rome. |

|

European botanical knowledge of pines apparently advanced very little for about 1,500 years from classical times until the early modern period. Most literature referred back to Theophrastus or was of a practical nature, concerned with subjects such as using pitch. The inhabitants of medieval Europe were intent on survival, and their philosophical thoughts were directed towards monotheistic religion rather than observations of the natural world for its own sake. They must have continued to think in generalized terms of pines (or firs, according to their linguistic background). Identifying trees for pitch, wood and other products was their purpose, and any fine distinctions they made are no longer apparent.

A pine tree and a crane in a Ching Dynasty Chinese painting by Tongshou. In Chinese culture, both tree and bird are auspicious and symbolize longevity.

The modern botanical idea of pine trees as a distinct group began to evolve around the end of the sixteenth century, with a more philosophical and careful reading of ancient texts. The Bauhin brothers, Jean (or Johann, 1541–1613) and Caspar (or Kaspar, 1560–1624), were physicians and scientists working in Geneva, sons of another Jean Bauhin who had been physician to the queen of Navarre. Jean Bauhin the younger, in his Historia Plantarum Universalis Liber Nonus (published posthumously in 1650), discussed the meanings of terms used by Theophrastus and complained of confusing terminology (as many concerned with pine trees continued to do). Caspar worked on botanical nomenclature, distinguishing between species and genus.14

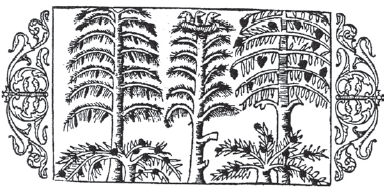

Woodcut illustration to Olaus Magnus, History of the Northern Peoples (1555), showing trees of the northern countries including a pine or fir tree on the left.

Herbalists and apothecaries, who needed to identify plants correctly, also left descriptions. Pierre Pomet in the latter part of the seventeenth century wrote about four pine species – the one cultivated for pine nuts, and three wild pines, including a diminutive, shrubby one called the wild sea pine.15

The idea of the genus Pinus was formally introduced into botanical literature when Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656–1708) described seven genera – Abies, Pinus, Larix, Thuja, Cupressus, Alnus and Betula.16 In Species Plantarum, Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) limited the genus Pinus to ten species. As a representative he chose the wild pine of northern Europe, Scots pine, and gave it the Latin name Pinus sylvestris, pine of the woods. The others he named were Italian stone pine (P. pinea), arolla or Swiss stone pine of the Alps (P. cembra), and two north American pines, eastern white pine (P. strobus, using an ancient word meaning ‘turning’, related to strobilius, the ancient Greek and modern botanical name for the pine cone), and loblolly pine (P. taeda, using Pliny’s word for torch). He also placed a cedar, a larch, two firs and a spruce in the genus. Given that several pine species were known to plant collectors by that time, it seems strange that Linnaeus did not describe more; it has been suggested that possibly he wanted to indicate a range of species in a field that was expanding.17

llustration to Rembert Dodoens’s Stirpium historiae pemptades sex (1616), showing the pine of the woods and the pine of the seashore.

The genus Pinus may be ‘a distinctly “natural” genus’,18 but it still needed elucidating, as Linnaeus’ inclusion of firs, larch, spruce and cypress, and the continued use of common names showed. ‘I discovered some pines which I am pretty confident are spruce-fir’, wrote the naturalist James Robertson in his journal on 10 June 1771 en route from Braemar to Banffshire through the Scottish Highlands.19 Circularity and tautology persisted in the names given to conifers; the early nineteenth-century botanist David Douglas referred to all conifers as pines, and spruce pine is still the common name for the North American species Pinus glabra.

Pines were confusing. ‘The difficulty and obscurity of the genus pinus have long been remarked and regretted by botanists’, said Aylmer Bourke Lambert (1761–1842) in what must be the most beautiful book ever published on pine trees, A Description of the Genus Pinus.20 Physically imposing and huge in size, with engraved plates by Ferdinand Bauer in the grand botanical tradition, it detailed all the pines (and other conifers) that the author had access to, either growing or as herbaria specimens. Lambert, a man of independent means, died in poverty as a result of following his obsessive interest in conifers. His fabulous book with its careful descriptions and glorious plates is, unfortunately, a bibliographer’s nightmare, ‘published in seven parts between 1803 and 1807 in a manner so irregular that copies vary in contents’.21 A second volume followed in 1824. ‘Difficulty’ and ‘obscurity’ marked Lambert’s publication, and unfortunately followed it as well. More species existed than Theophrastus or Linnaeus could have dreamed of, and they grew in a huge range of habitats. Before the late fifteenth-century voyages of exploration, Europeans had little opportunity to observe a wide range of pines. For people from northern Europe, they were simply the pine of the woods, Scots pine, and a very well-travelled inhabitant of the Mediterranean world might have had the opportunity to observe about twelve species.

By the late eighteenth century, all this had changed. North America, especially, was far richer in pine flora than anyone familiar with only Pinus sylvestris could imagine. Botanists accompanying exploratory voyages were followed by plant hunters charged with finding novel species that could be profitably raised for the European market. Their expeditions were often dangerous, as David Douglas’s dramatic account of his discovery of the sugar pine illustrated. Douglas knew that a gigantic species of pine grew somewhere in the mountains of northern Oregon, having seen both the seeds and a cone. In October 1826 he made an uncomfortable journey into the hills, and with the help of native people located some of these trees, called in the local Umpqua language natele. As the massive trees were too tall to climb, he took his gun and shot some cones down, the noise bringing several more hostile natives to find out what he was doing. Douglas retreated with three cones and some twigs as specimens, but regarded this tree as ‘the most princely of the genus, perhaps even the grandest specimens of vegetation’,22 and its discovery as a major achievement of his career. He named it Pinus lambertiana in honour of Aylmer Bourke Lambert. Douglas’s North American expeditions revealed other conifers to Europeans, including Monterey pine, ponderosa or western yellow pine, western white pine, Coulter pine and gray pine. Douglas himself came to an untimely end while collecting in Hawaii. This was a hazard of the plant hunter’s life; John Jeffrey (b. 1826), discoverer of the Jeffrey pine, vanished in Arizona in 1854. Expeditions to China and Southeast Asia also revealed pine species new to botany, although their impact was less profound on Western consciousness.

Scots pine engraved after Ferdinand Bauer for A. B. Lambert’s A Description of the Genus Pinus . . . (1803–24).

Discovery of the plant wealth of the New World, combined with developments in taxonomy, led to a complex tangle of literature on pine trees. The difficulty of dealing with pines was compounded by the number of common names given to individual species of these most useful and ornamental trees; for instance, North American eastern white pine became known as Weymouth pine when first introduced to England, after the first Lord Weymouth, who planted it extensively at Longleat in the early 1700s.23 The name is still in use, along with about 65 other common names in English, French, Spanish, German, Swedish and other languages. Some are obvious translations (Weymouths-keifer); others have local associations (Minnesota white pine) or refer to characteristics important to those who handle them (pumpkin pine, balsam pine), but others (such as the Hungarian simafenyö) are impervious to the non-specialist.24

Once the genus Pinus achieved recognition, botanists succumbed to a desire to divide it into groups, tribes or sections. The resulting forest of botanical literature is one of the most striking and daunting features of the history of pines. It is further complicated by changes in the botanical names given to individual species. The history of naming pines is complex: over time, botanical conventions about assigning names, the emphasis laid on particular aspects of the plants and the overall philosophy of classification have all changed to an extent remarked upon with despair even by botanists.25

A multiplicity of terms runs through the literature, usage and meaning depending on the author, date and purpose of the work. Species were demoted to subspecies, or re-elevated or divided in two because observations showed them to be sufficiently different; some were renamed in the twentieth century, when the International Rules of Botanical Nomenclature were changed, rendering previous names invalid. Scientific understanding of the genus is still incomplete: in the nineteenth century, when the desire to divide into subgroups took root, it was only half-realized. Not only were new species being discovered, but also the natural variability displayed by pines according to genetics and habitat was only just emerging.

Tree species that could be assigned to other genera were removed from the genus Pinus by major and logical subtractions. In 1754 the Scottish botanist Philip Miller (1691–1771) recognized firs (genus Abies) and larch (genus Larix) as separate, but spruces (genus Picea) were not separated out until 1824.26 Separating genera was one thing, but botanists continued to subdivide them. The path to present-day opinions on pines is littered with discarded proposals and analyses.

Criteria used by botanists to identify and classify pines were based on observable morphology – number of leaves in each bundle, shape of cones, texture of bark and more subtle features to do with microscopic and internal structure. From the mid-eighteenth century, when the French botanist Henri-Louis Duhamel (1700–1782) proposed a simple system based on leaves, botanists arranged and rearranged the species as the genus steadily increased in size. ‘No difficulty exists in the circumspection of the genus Pinus’, wrote George Engelmann (1809–1884);

floral characters unite with vegetative to establish it so firmly and so plainly that nobody fails to recognise the species belonging to it. But when we come to analyze and to group 60 or 70 species of pines which are known to us, we find that they appear so similar that all attempts to arrange them satisfactorily have failed.27

Engelmann was extremely thorough in his observations and divided the genus into two sections that he named strobus and pinaster.

Observations by late nineteenth-century botanists about the internal structure of pine leaves led to another division when Bernhard Koehne (1848–1918) also divided the genus into two sections: haploxylon for those with needles that contained one fibrovascular bundle (the tissue that conducts water and nutrients), diploxylon for those with two. These terms became important and influential. They were used by botanists and foresters for much of the twentieth century, until changes in the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature rendered them invalid, although the terms haploxyl and diploxyl are still used colloquially.28 But many terms – haploxylon, diploxylon, bifoliis, australes, parryana, Ducampopinus – are still enshrined in the literature of pine trees to trap and confuse.

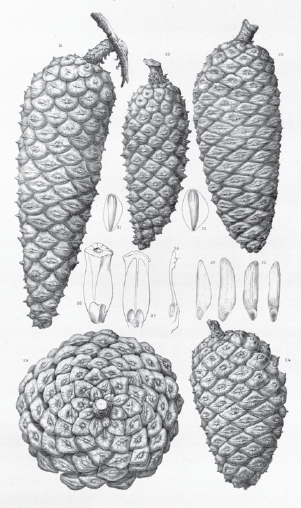

Cone of slash pine (P. elliottii) drawn by Paulus Roetter for George Engelmann’s Revision of the Genus Pinus and Description of ‘P. elliottii’ (1880).

Eastern white pine (P. strobus) engraved after Ferdinand Bauer for A. B. Lambert’s A Description of the Genus ‘Pinus’ . . . (1803–24).

The numerous systems proposed divided the genus into two (sometimes three) subgenera, in turn divided into sections and subsections. The problem was – and to some extent remains – in the observable characteristics used for classification for sections. ‘Some of the characteristics differentiating one system always interfere with those differentiating another’, observed Aljos Farjon.29 The concept of sections is important when considering species hybridization, as the majority of pine species will only hybridize within their own subsection. Botanists still disagree over whether some pines constitute species, subspecies or merely variants, and over the best way to organize them into sections.

Morphology, location and environment identify individual pine species but do not give definitive groupings. The interaction of genotype (the inherited potential) and phenotype (the actual development of the tree as dictated by environmental factors) leads to much variability in some species. Due to convergent evolution, especially for traits such as large, edible seeds distributed by birds, unrelated species separated by wide distances, mountain ranges or oceans can appear superficially very similar.

DNA analysis has helped unwind some details, but it is expensive and relationships between genes and, for instance, shapes of cones, can only be inferred. A more recent method known as clade analysis, studying the relationships of characters derived from common ancestors, produces branching diagrams (similar to ‘tree-of-life’ diagrams), which indicate relationships. This has led to more definitive ideas about how to subdivide the genus. From this mass of observation, description, data and conjecture accumulated over the past 250 years, the most consistent point that has emerged is the division of genus Pinus into two distinct subgenera,30 now known as subgenus Strobus (one vascular bundle per leaf ), and subgenus Pinus (two vascular bundles per leaf ). These are also sometimes colloquially referred to, at least in the USA, as soft or white pines (Strobus) and hard or yellow pines (Pinus) due to general differences in the wood. The idea of splitting the genus into two separate genera has been mentioned. Because this would require a change of botanical name for every species in the new genus, it remains only an idea – even taxonomists intent on order are not immune to the prospect of derision from their colleagues. Pines remain resistant to the attempts of botanists to tidy them up.