3. Does housing affordability really matter?

Can rising house prices be a bad thing? Surely they increase New Zealand’s wealth? Well, rising house prices can be a good thing – but too much of a good thing, as we know, can be bad in the long run.

Rising house prices make those who already own houses richer – that is obvious. But at the moment only about two-thirds of all households own the houses they reside in, and even this statistic is deceptive.1 Because home ownership is concentrated among the richer, older and smaller households, only about half of individual New Zealanders (those aged over fifteen) actually live in a home they own. As Figure 3.1 shows, in Auckland, only 43 per cent of individuals live in the house they own. Māori, Pacific peoples and recent migrants have very low home-ownership rates, as do young people under forty and people with low 67incomes. Those not owning their house – 57 per cent of people in Auckland – miss out entirely on the increase in wealth that rising house prices have created. That rise in house prices also reduces their chances of getting onto the property ladder.

In a more structural sense, if house prices rise too fast and out of step with income increases (as they have done in recent decades) housing unaffordability becomes a pressing threat to financial, economic and social stability. There are the obvious risks to economic and financial stability, if rapid house-price rises are followed by a slump. A less frequently discussed, but in fact larger and more insidious problem is that unaffordable housing sows the seeds of wealth inequality between generations and within future generations.

Given the growing reliance by young house-hunters on financial help from their parents, it seems inevitable that home ownership will increasingly become the provenance of the children of those who already own houses. Allowing the influence of hereditary sources of wealth to increase will exacerbate wealth inequality in New Zealand, driving a wedge between the haves and have-nots. The New Zealand housing system risks becoming a form of reverse welfare, where the rich will unduly benefit from higher house prices.2 In 2004, the most recent year for which we have data, 68the wealthiest 1 per cent of households owned 16 per cent of all the country’s wealth; in contrast, the poorest half of the country owned just 5 per cent of the wealth.3 The growing housing divide will only make this worse. This kind of inequality causes envy and reduces trust in the community, fraying the social fabric that is necessary for any well-functioning society, economy and country.

Figure 3.1 Home-ownership rate by group, Auckland (2013 Census)

* MELAA = Middle Eastern/Latin American/African.

** Home ownership by income band is shown for New Zealand total, as Auckland data was not yet available at time of publication.

Note: Over 60 per cent of households own their home, but they tend to be older and smaller households, meaning a smaller proportion of individual home owners (43 per cent). Lower home ownership for non-European ethnicities mirrors similar differences in incomes and other economic measures.

Source: Data from Statistics New Zealand, 2013 Census.

69The trend since the early 1990s has increasingly pushed New Zealand towards a new class system, with house owners – a kind of modern-day landed gentry – at the apex. This is a serious and persistent attack on New Zealand’s identity as an egalitarian society where social and economic success are open to all. Rising housing costs also push poor households further away from work and from attractive places to live, increasing the costs placed on these households and perpetuating a cycle of poverty.

Housing affordability also represents a threat to national prosperity. The often fortuitous returns accumulated by rising house prices risk making New Zealanders complacent and narrow-minded about ways to generate wealth. We need to confront the reality that the productive path to wealth lies not in sitting on property but in hard work and enterprise, across a range of different business settings – work that should generate higher profits and bigger incomes for all.70

Will house prices remain high?

House-price falls are possible. New Zealand has a rare history here, in that prices have never really fallen sharply or for a sustained period – we have never had a crash in that sense. But house-price falls have happened in New Zealand, especially in the regions in the wake of the GFC, and especially once prices are adjusted for inflation. In addition, major house-price falls have certainly happened internationally – and we should not be complacent about such a thing happening here. In Canada, for example, the city of Toronto had a real-estate boom and bust in the 1980s in which prices rose 113 per cent in real terms then fell by 40 per cent in the greater Toronto area and 50 per cent downtown by 1996. Fuelling the boom was rising immigration, strong jobs growth, more women entering the workforce, and the attitudes of a population who saw no likely end to the boom. But it collapsed due to a combination of fixed mortgage rates reaching 12.7 per cent, an early 1990s recession, a spike in unemployment and a drop in immigration. This cautionary boom and bust tale was recently reported as being circulated amongst Auckland’s financial networks, with some media and analysts interpreting this as a warning.4

In the last fifty years, there are only four years in which nominal (that is, not inflation-adjusted) New Zealand house prices have fallen, generally 71in exceptional circumstances: the tail end of a long recession in 1992, for instance, or the deep and long recession that lowered prices in 2009. But relative to the cost of living, prices have fallen far more often. This is because New Zealand has been through periods when inflation was high, and the cost of living rose sharply, but house prices did not rise alongside it. Once inflation is removed from the figures, we can see that in the last half-century, house prices fell in nineteen – nearly 40 per cent – of those years. (Care is needed with these figures, as they include an exceptional period in the late 1970s when both the economy and house prices performed poorly, due to oil-price shocks and economic mismanagement.)

More recently, house prices have fallen in many places from their 2007 pre-GFC peak. QVNZ tracks the house prices in some sixty-eight local areas, and its figures show that, as of early 2015, house prices are lower in 62 per cent of the regions in nominal terms than they were in 2007.5 Once we take into account increases in the cost of living, house prices are lower in 82 per cent of the regions. So even in New Zealand, we have evidence that house prices are not a one-way street – they can fall in many areas, and sometimes severely.

There are similar examples internationally. Compared to their 2007 level, house prices in 2015 are down sharply in Ireland, Spain, the 72Netherlands, Denmark and the US.6 In each instance, prior to 2007 house prices rose sharply relative to incomes, and lots of houses were built and traded; when the momentum ran out or an external shock hit, house prices fell sharply. The impact of house-price declines has not been even across these countries, but their combined experiences nonetheless provide some insights into the possible implications for New Zealand’s financial and economic stability, should a similar crash occur here.

Financial and economic risks of a downturn

A major fall in house prices can create chaos across an economy, as demonstrated by the GFC. Falling house prices, especially in the US, played a central role in widespread business failures, job losses and a global economic recession. This role was facilitated by the banking and finance sectors. They lent aggressively through the upturn in the housing market and the economy in general, but reduced lending and called back loans when the cycle turned down. This amplified the economic cycle, over-egging it on the upturn and driving it into the ground in the downturn. As house prices fell, many property developers and their financiers went bust, causing layoffs in construction, real estate, finance and other sectors that supported 73house building, such as forestry and building materials firms.

There is a familiar pattern in such crises. Initially households become more cautious; they reduce their spending on discretionary and luxury goods, and reduce their borrowing – not just in mortgages, but also credit card use and other consumer finance. They tend to spend only what they earn, rather than borrowing to spend more. This hits retailers, non-mortgage financiers and those who support these sectors. But as the downturn broadens, job losses mean households spend even less, businesses stop investing and hiring, and a recession ensues. The more debt people had previously taken on, the worse the impact. There is not always a clear sequence of events – the economy is a complex international web of millions of individual decisions. But the end result is inevitably a recession.

A vicious cycle ensues and broadens, as banks become risk-averse, reducing their lending, and tightening their lending criteria not just for house-related borrowing, but also for businesses. The credit drought is worst for small businesses. This change in banks’ lending practices amplifies the impact of the housing downturn on the economy and the financial sector, and leads to a long and deep recession.

Banks, facing lower profits and increasing 74numbers of defaults in their mortgages (and potentially other lending areas), can in some cases go bust. The risk of such a scenario is low, but the cost would be high. Even if customer deposits are not lost, confidence can evaporate. This happened in the UK in the run-up to the GFC. In 2007, Northern Rock, the country’s fifth largest mortgage lender, faced a run on its deposits, the first experienced by a British bank since 1866.7 There were queues of people waiting to withdraw their funds – something the bank could not cope with, as like all banks it had lent many times more funds than it held and simply did not have the money to give out.

In the GFC, nearly 300 US banks with assets of around US$540 billion failed, accounting for around 4 per cent of all bank assets.8 The situation in the US was worsened by borrowers’ ability to walk away from mortgaged houses. In the US, mortgages are secured against the house in what is known as a non-recourse loan, rather than against the future income of the borrower, as they are in New Zealand. This meant that when a house was worth less than its owner’s mortgage, it made more sense for the owner to walk away from it than keep repaying the mortgage. Banks received a lot of ‘jingle mail’, the colloquial term for the packages in which mortgage holders sent their house keys to their bank. In New Zealand, by contrast, borrowers 75remain liable to repay the debt, so in the event of a house-price crash they would have to knuckle down, cut back in other areas, and only default on their mortgage as a last resort.

As housing investment has come to dominate the financial sector, the impact of house-price changes on the economy has become more important. A study that looked at nearly 150 years of data across seventeen countries found that households are borrowing more, and mortgages have become a larger share of all lending.9 As we saw in Chapter 2, in New Zealand mortgages have risen from less than 10 per cent of all bank lending in the 1970s to 25 per cent in the mid-1990s, and over 50 per cent in 2015. This means that financial and economic stability has become increasingly linked to housing booms, which are typically followed by deeper recessions and slower recoveries.

Another recent study has found that, internationally, housing booms have become longer and their subsequent busts are more painful for the economy.10 The same pattern applies in New Zealand, where house-price cycles (the time from the bottom to the top of the market) are getting longer. The typical cycle in New Zealand has gone from around three years in the 1970s to six years in the 2000s boom, and the latest cycle is four years and counting.

This point is especially important because 76the international evidence suggests that action should be taken within the first six to seven years of a boom.11 We are now in that phase where coordinated action by policy-makers is necessary to avoid the costs of sharply accelerating house prices and the risks of a potential future downturn. If the poor policies that lead to housing bubbles are not fixed, the booms get longer. The longer house-price booms last, the more speculative they become. The more house prices rise, the more people speculate that house prices will rise further and the more they buy houses at even higher prices, typically with high levels of debt. And that just makes the inevitable bust even more painful when it finally arrives.

Housing debt in New Zealand

New Zealand’s levels of housing-related debt are at record levels. Total mortgage debt recently passed $200 billion – a figure that has doubled in less than a decade.12 Very high house prices put pressure on people to take on unmanageable amounts of debt. Putting pressure on households to do this, to step outside their financial comfort zone to buy a home, is damaging people’s quality of life. They may own a home, but the huge sacrifices they make in terms of other spending puts them under severe financial stress. For many families, having both parents in work is now a necessity, not a choice. Many of these 77parents must also now commute longer and longer distances, as affordable houses are increasingly found on the outskirts of major cities. As a result, some families now leave their young children in care for eleven hours a day, with uncertain long-term developmental consequences.13

Saving money on top of paying all the bills is nigh-on impossible. Instead many home owners borrow against house-price increases in order to buy more houses, do renovations, buy cars or go on a holiday. Taking on debt has become normal. This means that households are more vulnerable to an economic shock that leads to job losses, increases in interest rates or house-price falls. This in turn creates risks for the economy and the banking system.14

It also creates more risks across an individual’s lifetime. In today’s environment, where inflation is carefully controlled, paying off mortgages with the benefit of high inflation is no longer possible, as it was in previous decades. In April 2015, the median house price was $720,000 in Auckland (the average house price, around $810,000, is higher than the median because sales of some very expensive houses pull it up). The median household income for a couple in their thirties was around $75,000. This means that if they spent a third of their income on mortgage repayments, they wouldn’t even cover the interest payments. Instead, young 78home buyers must now spend more than 40 per cent of their income servicing mortgages, and may not be debt-free for another thirty-five years. And spending more than a third of your income on a mortgage leaves little room for a comfortable lifestyle and maintaining some precautionary and retirement savings. Young people now often have to sacrifice more than ever to get onto the property ladder.

More broadly, New Zealand households have high levels of indebtedness in housing. At the end of 2014, households had $1.60 of debt for every dollar of their income. This is up from $0.56 in the early 1990s, before the long period of unaffordability set in. In the early 1990s borrowing was low because houses were more affordable, mortgages were hard to get and interest rates were very expensive (well over 10 per cent a year).

There is nothing inherently wrong with borrowing money. Debt can, of course, be useful to purchase a big item now and slowly pay it off. Debt only becomes a problem if you can’t make the regular repayments or if the asset purchased turns out to be worth less than the debt.

Debt can, however, have a more insidious effect by inflating ‘bubbles’ that eventually pop. Hyman Minsky, an economist so famous that he inspired the term ‘Minsky moment’ (a sudden major collapse of asset values), argued that there were five 79distinct stages of the credit cycle: displacement, boom, euphoria, profit taking, and panic.15 The cycle starts with displacement, which is what happens when something new excites people, like a strongly growing economy. People borrow and invest, so banks lend more and the cycle ramps up, leading to a boom. The boom leads in turn to euphoria – the point when every man and his dog are in, and taxi drivers dole out advice on the best suburbs in which to buy houses. Some smart investors start to profit – and then something breaks, leading to panic. But as with a crowd trying to leave a stadium after a game, most people can’t get out quickly. The early leavers get out with their shirts untouched, but as panic sets in, prices fall and assets no longer sell.

What Minsky describes in the lead-up to the panic stage is basically Ponzi finance, which requires that asset prices keep rising, inflated by new money, in order to be able to pay back the debt. And we can see this in New Zealand. The Auckland market has become so expensive that rental income from an investment will only just cover the usual outgoings in rates, insurance, maintenance and vacancy. Mortgage payments can’t be covered from the rent, meaning the investor needs to sell the property at a higher price to be able to pay the debt and still come out ahead. In this Kiwi version of Minsky’s Ponzi scheme, recent investors in the 80Auckland housing market are vulnerable because they have taken on debt they can only pay back if house prices keep rising. That is not guaranteed to happen – and it is not good for the rest of society if it does. If house prices keep rising at their current rate, housing will be out of reach for most, and, as previously discussed, mortgage payments will rise from half of income currently (for the average house and the average family) to all of a family’s income within the next decade. The Ponzi scheme is unsustainable, whichever way we look at it.

A culture of property investment, against all odds

These problems are so acute because, while other countries face similar challenges, few have such an obsession with housing at the expense of all other investments (even Australia, another housing-obsessed nation, has fewer household assets in housing than New Zealand).16 New Zealanders are so obsessed with housing that we do not have many other investments like shares and bonds. This means our businesses do not have the same access to the risky capital they need to grow and create sustained jobs and prosperity.

New Zealand’s shallow capital markets are a long-standing issue. Added together, the companies on our stock market are worth around 40 per cent 81of the size of our economy. This is very small compared to Australia, the US, the UK and Canada: in all those countries their stock market is about the same size as their economy.17 And the unsophisticated nature of the capital markets we do have means our businesses don’t have access to the same variety of capital as their international peers. This puts New Zealand businesses at a disadvantage, making our economy less competitive.

Our economy is so shallow in part because investing is seen mainly as being about residential property. Few have the knowledge, capability and desire to make alternative investments. As a result, Kiwis tend to have very concentrated investments in one asset (their house) or one asset class (many houses). Culture plays a big part in this, as does low financial literacy. Other hindrances include the fear of having to deal with brokers, paying numerous fees, dealing with complex tax rules, foreign exchange translations and money laundering rules.18 We are starting to see some improvements in financial literacy thanks to KiwiSaver, our voluntary superannuation savings scheme. Financial savings are increasing and a new generation of investors are seeing another way of saving. But we have a long way to go.82

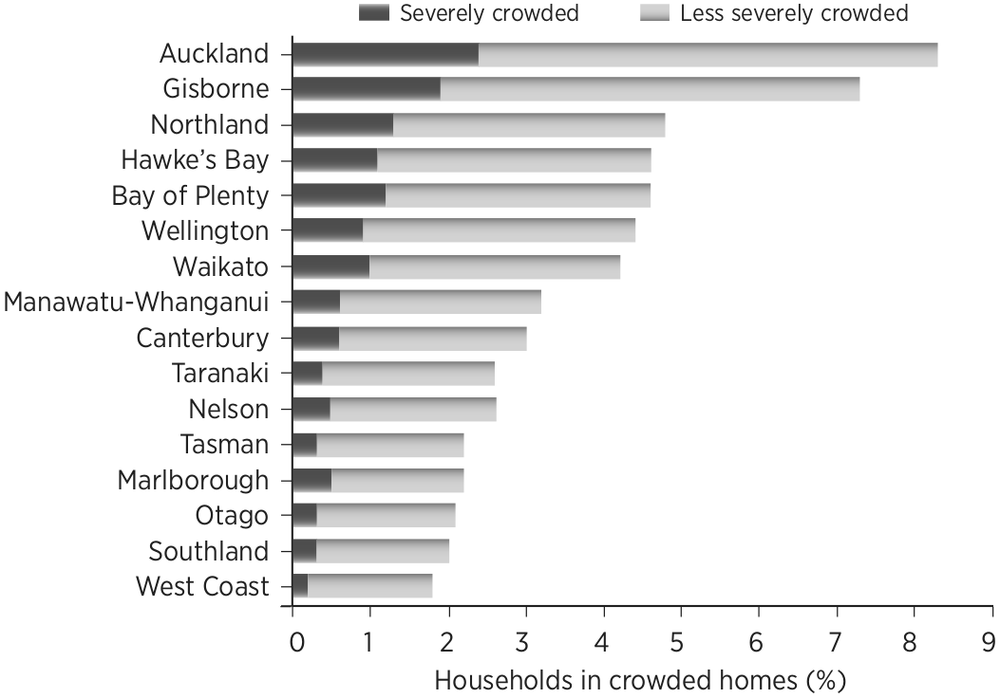

Figure 3.2 Proportion of households living in a crowded home (2013)

Note: Some households are forced into living in places too small for their needs, as they cannot afford a suitable home. The cost of housing, the cost of transport, location and many other factors are among the causes. Crowding is most prevalent among people on low incomes, who are already spending a large share of their income on rent and cannot afford a larger home.

Source: Data from Statistics New Zealand.

The risks from rising house prices

High house prices are also a problem in the here and now – especially when they put housing out of the reach of so many. There are pressing reasons for urgent and sustained action to find solutions that will work and stick.

The consequences of unaffordable housing are social, economic and generational. The first social cost falls on the poor. When house prices rise, they tend to rise in places close to work 83and other amenities, such as train stations, sites benefiting from motorway access, ‘good schools’ or otherwise generally ‘desirable’ places to live. The rise in house prices starts in the most desirable suburbs and ripples out through surrounding areas. These nearby suburbs may in the past have provided accommodation for poorer households, who thus benefited from being reasonably close to the amenities listed above. But as these suburbs have become more expensive and gentrified, the poor have been pushed further and further out, far away from amenities – but still having to squeeze into small houses and spend more of their income on housing.

As shown in Figure 3.2, over 8 per cent of Aucklanders are now living in crowded homes. Crowding is less of an issue in other parts of New Zealand, although it still tends to be high in places with high poverty rates. Living in a crowded home can increase the risk of infectious diseases like tuberculosis, meningococcal disease, rheumatic fever and childhood pneumonia.19 It is also linked to mental health issues and strained household relationships.20 If poor households do try to live near the places that give them access to work, good schools and other amenities, they often end up spending so much on housing that things like doctor’s visits become a luxury.21 Instead they wait until illnesses are more serious and go to the A&E 84at the hospital instead. This is not only bad for their health, it is expensive for the economy, since every A&E visit costs far more than a GP consultation and early intervention.

Frequently the housing that is available in the outermost suburbs is of very poor quality, and families are forced to shift regularly in search of a decent home. This has many negative consequences, such as children being forced to change schools, which damages their connections with teachers and other pupils and thus their ability to learn.

Living further away from the centre is also expensive in that it often forces households to invest in a car that they can barely afford or spend more time and money getting to and from work. Poor households typically spend 10 per cent more time travelling to and from work than their more affluent counterparts.22 And each kilometre away from the city centre increases the cost of an individual’s commute by nearly $750 dollars a year.23 The McKinsey Institute has argued that to maintain a good quality of life, no one should commute for more than one hour.24 But Auckland’s sprawl and level of congestion is such that even a supposed 30-minute commute takes an additional 25 minutes per day (or 95 hours per year) during peak times.25

Having to live so far from the centre with 85inadequate public transport is, in other words, putting a financial burden on low-income households. This is especially true for the poor who work far outside city centres and need to catch several connecting public transport routes to get to work. Furthermore, lacking savings or access to normal forms of credit such as bank lending, poor households often resort to expensive unsecured financing. Owing to weak financial literacy, some households may not understand the full financial implications of this borrowing, and end up paying a lot more than they should in fees, interest and penalties.26 More generally, when such households spend a large amount of their income on housing and transport, they have limited time and money available to invest in themselves, whether through undertaking further education, building social networks, or other means of life improvement.

Housing and mobility

Unaffordable housing can either reduce mobility, by limiting the options for people to move into certain areas, or increase it in a negative sense, by spurring people to leave for other places in search of better and cheaper accommodation. These constrained choices can affect people’s career opportunities and the economy suffers too – as it creates a dearth of qualified candidates to fill job vacancies.86

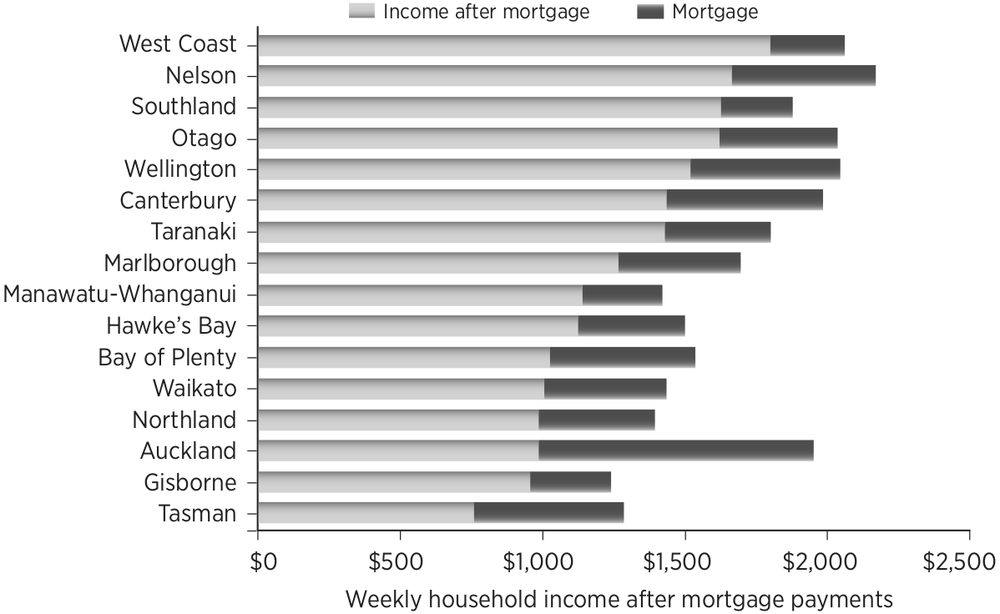

Figure 3.3 Average weekly household income after average mortgage payments per region in 2014 (20% deposit, 30-year term, typical mortgage rates)

Note: Figure 3.3 shows the weekly household income, ranked by income after mortgage payments, assuming typical terms for the average house. Even though Auckland is one of the highest earning regions, it is near the bottom once housing costs are accounted for. However, this static view does not capture greater lifetime income potential in larger markets like Auckland, where income and career advance opportunities are greater.

Source: Data from Statistics New Zealand, QVNZ, RBNZ and NZIER.

Auckland is experiencing strong growth and is short of workers in many skilled sectors. Most other parts of New Zealand are not experiencing this type of growth and have an excess of workers. The option of moving to Auckland to take advantage of these job opportunities seems a no-brainer – until we add housing into the mix (see Figure 3.3). Someone moving from, say, Southland to Auckland cannot 87hope to sell their house and find something similar in their destination city. The average house costs around $200,000 in Southland, while the typical price in Auckland is almost four times higher, at $810,000. This huge difference in house prices makes it difficult to access the employment possibilities that the country’s biggest city provides.

Not only are people put off moving to Auckland, many Aucklanders are leaving for other regions – as well as heading overseas. Once one takes into account the fact that mortgage payments will be lower outside Auckland, incomes are effectively higher in many of those other places. For people in professions that are not in some way bound to Auckland, there is an opportunity to move out of the city and improve their incomes and, in all probability, their lifestyle. Others can move for retirement or study. Whatever the motivations, Auckland loses more people to the regions than it gains: the 2013 Census showed that it lost just over 1,000 more people per year (between the 2006 and 2013 Censuses) to other regions than it received from them. The main beneficiaries have been the neighbouring regions Waikato, Northland and Bay of Plenty.

This ‘reverse’ mobility, alongside reduced mobility in general, is bad for the economy. In places like Auckland, which is where many of New 88Zealand’s housing unaffordability problems are concentrated, the high cost of housing reduces the city’s attractiveness as a place to live, play and do business. High and rising house prices are increasingly a cost disease. It is difficult for businesses to hire and retain qualified workers – and this limits the potential of the economy.

Some would argue that this is essentially an issue for Auckland (where house prices are the most out of step with fundamentals) and has few implications for the rest of the country. But Auckland is our one city capable of competing with other world centres, and a major driver of New Zealand’s economic success. What happens there matters for the whole country. In addition, Auckland’s house prices are high mainly thanks to policies that are national in scope, so the policy responses will also be national. We saw this 2013, when the Reserve Bank restricted banks’ low-equity lending through its loan-to-value restrictions.27 This was meant to slow the Auckland housing market, but according to sources in the banking sector, it in fact disproportionately affected lending in the provinces outside of Auckland. Recognising this, the Reserve Bank has since tweaked these rules to ease restrictions for the provinces and tighten them for Auckland, effective October 2015.

In reality, Auckland’s rampaging house prices are a symptom of deeper problems in our rules 89and regulations around land supply, financing and taxes. All New Zealand is affected by these rules and regulations, and getting the right fix is important for us all.

Social housing

This book’s discussion of ‘affordable’ housing is aimed principally at the problems faced by middle and lower-middle income households currently locked out of the housing market.28 But we have also discussed the challenges that unaffordable housing creates for the poorest households, and the way they are being pushed out into suburbs further and further away from work and other amenities, leading to increased segregation between the rich and poor, and sowing the seeds of future social and economic ills.

At certain points in New Zealand’s history, the difficulties faced by poorer households have been addressed in part by major programmes to build social housing – that is, housing owned by the state and rented at below-market rates with an explicit social purpose. The need for that kind of housing remains high. There are currently about 5,600 people on the waiting list for social housing, and that does not include ‘lower priority’ applicants who, following a recent change of policy, are no longer recorded. The households on the waiting list generally do not have suitable 90or adequate housing at present; many are in extremely sub-standard accommodation. State-house tenants (and applicants) also tend to have high and complex needs. They are dealing with poverty, but also other challenges including mental illness and family breakdown. Many of these tenants simply do not have the capacity or capability to enter the private rental market.

However, as a proportion of the overall housing stock, social housing has been diminishing for decades. Housing New Zealand currently owns or provides around 69,000 homes, the same number it did in 1991. Yet the number of households in New Zealand has risen by nearly a third since then, implying that about 20,000 more social houses would be required to meet the same need as was met in 1991.29

There are arguments to be made for increasing the amount of social housing, whether it is owned by the state or by third parties such as non-governmental organisations. In other countries, notably those in Northern Europe, a large proportion of all houses are social housing, and living in social housing is an option available to a range of households, rather than simply the poorest, as is the case in New Zealand now. Social housing was in fact also aimed at middle-class families in the early years of New Zealand state housing. For example, Caroline Miller of Massey 91University, a researcher with a strong interest in the history of planning in New Zealand, told us how an early state house resident complained that his house was pretty good, but it would be better if it had a garage for his car. Cars were quite an expense in those days, indicating that state housing cannot have been just for those without any other housing options but for the aspiring middle classes too.

However, in this book, we do not enter into the arguments about social housing in much detail. Our main focus is on affordability for the broad market for housing, and increasing the supply of social housing would not improve housing affordability in that sense. More social housing would mean more options for the poorest households, potentially easing pressure on rents at the very lowest end of the rental market. But since in most suburbs those renters are not generally in competition with prospective home buyers, it is not clear that more social housing would reduce competition – and thus prices – in most housing markets.

When it comes to policy solutions, we are focused on those that will fix the fundamental issues driving unaffordability, rather than on social policy, the area that has social housing within its remit. The discussions around social policy are highly complex and, whether rightly or wrongly, there is little political appetite for a major programme of social housing construction in New 92Zealand. Neither major political party is proposing to increase the number of social houses in a way that could significantly affect the wider housing market. For the moment, then, it seems necessary to focus on other options.

A disenfranchised and desperate generation

One of the biggest impacts of unaffordable housing is that it has created a generation who are both locked out of home ownership and – because of decades of policy neglect – are unable to find somewhere decent to rent. This is Generation Rent – and they are renters not by choice but because they have no other options.

The stresses felt by Generation Rent are many and various: a feeling of disenfranchisement and desperation at being unable to realise the Kiwi dream of home ownership; not being able to save enough for retirement or a rainy day; and being forced to rent, which remains significantly inferior to ownership in terms of stability and comfort. This situation is already creating intergenerational envy, as well as rancour towards fortunate home owners within the younger generation and, if left unchecked, will eventually become an intergenerational war fought on the political field.

One of the most pressing issues for Generation Rent is that, prevented from owning their own 93homes, they are unable to access New Zealand’s traditional route to financial independence. With no cultural norm to draw on around financial savings and a shallow and unsophisticated local financial market, those unable to buy affordable houses are simply not saving for old age, leaving little time and money to make the small additional financial savings that would make retirement easier. This means that as the young renters go through life, they will not, as earlier generations did, accumulate savings for retirement or a rainy day. Those who buy will also be in debt for longer, making them vulnerable to changes in their life circumstances, such as sudden job loss, illness or a sharp increase in interest rates.

Generation Rent also feel that they are missing out on the Kiwi dream of owning their own home. Cultural norms and an overwhelming expectation of home ownership means that those who cannot buy a home feel excluded from society. Societal expectations may not have much weight in some economic circles, but it is these expectations that bind communities together and shape how they function. Cultural norms signify the positives we strive towards and the negatives we seek to avoid. In the absence of a complete set of spoken and written rules for how things should work, these norms smooth the functioning of society. Because they are integral to our sense of who we are, they 94may be difficult or impossible for individuals to counter. They may also embody entirely legitimate aspirations. So while Generation Rent has been described as a generation of ‘property orphans’, a more accurate description would be ‘cultural orphans’ – people who cannot have what their parents had.30

With home ownership sliding further from the grasp of more and more New Zealanders, as evidenced by a home-ownership rate that has fallen to the lowest level since 1951, many people feel disconnected from the traditional norm of what it means to be a Kiwi. This failure to uphold cultural norms creates massive psychological pressures, leading to feelings of abandonment and exclusion. In a New Zealand Herald article, the prevailing sentiment was captured aptly in an open letter from an anonymous ‘first-home hunter’:

We have decided to leave New Zealand as it’s not fair to us anymore. This country has failed our generation and the oldies aren’t keen to solve the issue. We have a feeling of disenfranchisement and desperation that is hard to describe.31

There are also very real family and developmental implications that may be seen in decades to come. Very high house prices mean that those young families that manage to buy a house often do so by taking a large mortgage, living very far away 95from work in a sub-standard house and having both parents working in order to make ends meet. As a result parents are spending less time with their children and as a family, and very young children are left in care for long periods as parents go back to work. While there are well-documented benefits to early childhood education from about the age of three onwards, we do not yet know what will be the impact of separation from a parent or guardian at a much earlier age.

Generation Rent feels especially aggrieved about the housing situation because it is not of their own making. There are myths that young people should just move further out from the centre to find an affordable house, or that they are feckless with their money.32 These charges are not only unfair, they are in fact false. For example, while Auckland house prices have more than doubled since early 2000s, incomes for a young couple have only increased by a third. That is not a problem that young house-hunters can control. There is also little evidence that the younger generation are freewheeling big spenders; rather, they are putting more towards rent, electricity and transport than previous generations – hardly profligate spending.33

Generation Rent represents what is essentially a typical ‘insider-outsider’ problem. Those inside the home-ownership system have done very well out of successive years of house-price increases and will 96do everything in their power to protect these gains. Those on the outside of home ownership risk being locked out forever. Solving this insider-outsider problem is one of the greatest challenges facing the housing market.

Within current generations, there is a growing divide between the ‘landed gentry’, as we have labelled them, and the rest. This is one of the amplifying problems faced by Generation Rent. Increasingly, it is only the children of home owners who will be able to own homes, through either direct bequests or financial help. Already, we are seeing the ‘bank of mum and dad’ as an increasingly common prop for young house-hunters – one that is available only to the wealthy, of course.

With housing increasingly unaffordable, we are sowing the seeds of substantial inequality between generations and within future generations. As the number of those excluded from home ownership grows ever larger, we risk a property-hoarding minority controlling much of the wealth, and using their position to influence politics – and thus the setting of rules and regulations – in order to protect and perpetuate this wealth. Local representative democracy sometimes appears to be only a thin veneer laid over the long-standing influence on politics exerted by the privileged few.

As gaps between and within generations grow, so too will discontent. Ultimately, politics is likely 97to be the great leveler. As in the past, when political parties have surged into existence to represent the rights of the majority working classes against the landed gentry, the next political shift may seek inspiration from the feelings of exclusion and despair within Generation Rent.

One of the things that Generation Rent may – and should – demand is a new and fairer settlement for those in rental accommodation. At the moment, renting is a poor substitute to living in your own home. Renters enjoy far less stability and fewer of the comforts of home, lacking security of tenure and the freedom to have pets or make minor alterations to their house.

Our current rules are designed for transient and short-term renting. This is appropriate for young people whose lifestyles are changing rapidly. Think of students flatting during university term time but going home for the summer holidays. Or a young woman living in a cheap flat as she starts her first job, but moving into a nicer, bigger place as her career progresses and she forms a relationship and a family. This is where renting becomes so obviously a poor substitute – once there is a family, the need for security is far more pressing. Community and support networks become more important in the later stages of life. Moving frequently is expensive and disruptive, and is not suited to the lifestyles of people in the older age brackets, particularly those 98with children. Unsurprisingly, the evidence shows that it is precisely these families with children – many of whom are renting – who are the least satisfied with their housing.

Yet there are many good reasons why people might want to rent. As discussed in Chapter 1, it allows households geographic flexibility when jobs change. It also gives them some financial flexibility; they do not have to deal with maintenance and other costs, there is no need to save for a large deposit, and they are spared the risk of a major downturn in the housing market.

At the moment, renting is less desirable than owning: an inferior option rather than a genuinely viable alternative. But we can change that – and we need to. Of course we should also take steps to make owning a house more affordable, through difficult and courageous reforms of rules and regulations. But we must also increase the range of genuine options open to individuals and families by making sure renting works much better for them than it does currently. This will involve changing policy, changing cultural expectations so that those who rent are not looked down on, and making other forms of saving easier to access so that renters can enjoy the same financial stability as house owners.

Any actions that address housing affordability will require some time to take effect. But unaffordable housing is, right now, leaving 99many families stranded in unsuitable rented accommodation. They need action, and they need it quickly. There are existing examples of good rental terms and conditions in our own commercial property market and internationally in renting nations like Switzerland and Germany. Let’s build on them.