Distinction and Patriotism: Muṣṭafā Kāmil and the Making of an Arab Prince

Sunday evening the prince went to the khedivial playhouse which is known as the Opera to watch a great play. When the audience saw him they all stood up in admiration and greeted him with clapping and shouting. The music band played four times his greeting while the clapping and shouting continued. The playhouse was full with locals and all kinds of foreigners but only a few British employees and administrators were present. And this was a sign for Lord Cromer about the feelings of the foreigners towards the prince after he knew the feelings of the locals.1

Thus did Mīkhāʾīl Shārūbīm, a Coptic judge, describe the presence of Abbas Hilmi II in the Khedivial Opera House sometime in January 1893. His Arabic account confirms the New York Times article with which this part of the book started. He reveals a mixed audience in the official theater of the khedivate, the mastery with which the young khedive used publicity, and an old-new Arabic title: the prince (amīr).2

In this chapter, we follow the peak and end of Arab patriotism in Ottoman Egypt. The sudden death of Tevfik in 1892 helped to complete the restoration of khedivial legitimacy. However, patriotic intellectuals retained an uneasy relationship with khedivial authority. The symbolic figure of this relationship was Muṣṭafā Kāmil who was to become the first Egyptian nationalist politician. Another forgotten, tragic figure is the Sufi leader Muḥammad Tawfīq al-Bakrī (1870–1932). The three men—the khedive, the sheikh, and the politician—were of roughly the same age. Here I focus on Abbas Hilmi and Kāmil only.3 Their entrance into politics defines the end of patriotism and opens a contested era of anticolonial nationalism.

The young Kāmil imagined the young khedive (they were of the same age) as a compatriot Muslim Arab ruler who represented both the imagined nation and the Ottoman caliph. Ottomanism and khedivial authority are sometimes identical in this period. The men and women who shared or accepted this imagination—the audience of patriotism—belonged to the upper strata of Egyptian society, mixed with colonial elites, and were characterized by distinct cultural markers. This is the period in which the elite generation of interwar Egypt was formed and norms became established which have been governing Arab eliteness until today.

The early 1890s was also characterized by a theatrical boom in Arabic. Female writers, such as Zaynab Fawwāz (d. 1914), appeared not only as playwrights but also as critics in journals. There were more private stages, and the first theater building in Cairo was also built for performances exclusively in Arabic. As the playwright Maḥmūd Wāṣif wrote in his introduction to a 1900 edition of Hārūn al-Rashīd, there was an “Arab revival in Egypt” (nahḍa ʿarabiyya fī Miṣr) “in the shadow of his Highness the Khedive.”4 Plays were translated and composed in Arabic, which challenged public norms and textual standards. This chapter cannot pay justice to the richness of Arabic production and staging of plays in various settings. I only follow here the peak of patriotism through elite figures in order to catch the governing norms and framework of politics during the first years of Abbas Hilmi II’s reign.

MARKERS OF DISTINCTION

How should we define the patriotic elite in late Ottoman Egypt? In this section, I draw on the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of distinction and various forms of capital in order to paint a picture of the elite audience, and in general, to describe late-nineteenth-century Egyptian urban society.5 Bourdieu argues that “cultural capital” is a form of accumulated knowledge, convertible into economic capital, but which also represents an investment by external wealth into the personal habitus.6 While the embodied symbolic value within an individual’s personality is usually called “refinement” and “urbanity” (the original meaning of Arabic adab and ʿumrāniyya) its function is more than a convertible asset. Shared norms and shared knowledge establish a solidarity between the possessors of the same cultural capital. In turn, solidarity and markers establish a community of norms. This imagined community of norms was discursively bound by the idea of the homeland. Yet, while the patriotic collectivity was imagined as everyone’s nation, in practice it was the possession of the few who shared these norms.

I connect cultural capital to elite class formation.7 I use the term “class” here as derived from Arabic discourses in the 1890s regarding economically distinct groups. The Arabic word for “class” is ṭabaqa, literally, the “layer” of society; it has been used to denote various groupings of peoples and things, the typical example being the individuals who belong to one profession (like the poets) or to one generation (like ninth-century scholars). Ṭabaqa from the 1890s started to denote also “classes” of society in Arabic. A new, French-inspired sociological taxonomy replaced the old social categories, such as ruler and ruled, or the distinct elites of zevat and aʿyān, with that of one single patriotic elite, the middle class, and the poor.

Poor, Not Poor, and the Middle

A discussion arguing that “the rich” had a political responsibility towards “the poor” in Egypt started as early as the 1870s, as we have seen in the theater play of ʿAbd Allāh Nadīm in chapter 5. (The ancient Muslim pious obligation is not discussed here.) Two decades later, in the 1890s, articles in the journal Miṣbāḥ al-Sharq with titles such as “The Sons of Princes” condemned the increasingly lavish lifestyle of the sons of zevat.8 Theoretical articulation of the new social taxonomy was perhaps first expressed by Aḥmad Fatḥī Zaghlūl, the brother of the later nationalist Saʿd Zaghlūl in 1899.9 In the Arabic works of the time, the word “middle” (wasaṭ) denoted an imagined social layer between rich and poor. An often quoted work, The Present of Egyptians (Ḥāḍir al-Miṣriyyin, 1902) by a certain Muḥammad ʿUmar underlined the importance of the middle layer (al-ṭabaqa al-wusṭā) in patriotism. He thought “they are the blossom of the nation” (zahrat al-umma).10 ʿUmar understood the middle mostly in terms of function and institutions. The institutions include those–which, at that time, were related around the world to bourgeois patriotic activities—al-Azhar (a university), courts, the trade, and Arabic journals.11 The destiny of the middle class, according to ʿUmar, was patriotism (waṭaniyya), which was to be produced by the knowledge learned in these institutions; furthermore, only this ṭabaqa could overcome religious divisions and achieve independence through national unity.

As Ryzova shows, Egyptians born in the 1890s in the countryside often used the category of the middle class, or at least a perceivable difference between their family and both the poor and the elite, to describe their background in hindsight.12 Rural notables, however, were often aware of their high social status and wealth. For instance, the later politician, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ʿAzzām (1893–1976), who was born in an aʿyān family, realized that he was from one of the “highest families.”13 The British occupation was generally favorable for the local landowning elite by further securing their lands and rights gained earlier. Ultimately, it was the aʿyān disguised as middle class that would lead the national independence movement.

Egyptian intellectuals, often from aʿyān background, used literature to define themselves. Rising Egyptian novelists, Samah Selim argues, expressed themselves as distinct from the poor: “The narrative representation of this class’s social environment (al-wāqiʿ al-ijtimāʿī) was one of the mechanisms by which this process of self-reflection unfolded. The fallāh provided the raw material for the new nationalist literary imagination, while also figuring as an archetypal narrative other for the cosmopolitan, urban subject.”14 Michael Gasper affirms “the power of representation” through various texts in the 1890s in which peasant characters talk about progress and politics, and argues that “the new Egyptian [was] defined . . . by a new kind of social consciousness.”15

Nation-Ness, Religion, and Charity

An Arabic journal remarked in 1893 that “the [charitable] societies are the strength of the nation (umma).”16 The wealth and changing culture of the rural and urban elite was articulated in public rituals of solidarity. The interplay of charitable societies and Arabic theater performances provide a window into this articulation. Patriotism and philanthropy were connected as a religious and class activity in order to finance education and welfare services since the government did not provide enough.17

The most visible charitable society was the Syrian Orthodox Society (al-Jamʿiyya al-Sūriyya al-Urthūdhuksiyya), established in 1875 or 1876 in Alexandria. This organization had attracted 34,000 subscribers by 1880. In 1881, Armenians in Egypt also established their own charitable society (al-Jamʿiyya al-Khayriyya al-Armaniyya).18 Muslim Egyptians grouped in two main societies in late 1870s Cairo: the Society of Benevolent Intentions (Jamʿiyyat al-Maqāṣid al-Khayriyya) and the Muslim Charitable Society (al-Jamʿiyya al-Khayriyya al-Islāmiyya). In 1880, Sheikh Muḥammad ʿAbduh underlined the usefulness of such organizations for Muslim Egyptians and asked for government support.19 ʿAbd Allāh Nadīm, in his play al-Waṭan (1879), also suggested the charitable society as the best social form for (nongovernment) education.20 Such societies were important sites of political discussion before the ʿUrābī revolution. Later, among the post-1882 societies, in addition to the Syrian Orthodox, we find the Orthodox Coptic Charitable Society, under the presidency of Buṭrus Ghālī, and the Roman Catholic Charitable Society, with president Bishāra Taqlā, while the Muslim charity organization of the 1880s was the Tawfīq Charitable Society, under the honorary presidency of heir presumptive Abbas Hilmi.21 In the 1890s, the most politically important Muslim society was the Islamic Charitable Society (al-Jamʿiyya al-Khayriyya al-Islāmiyya), established in 1893 by mostly aʿyān-origin lawyers whose main goal was to finance education. They often used both the al-Azbakiyya Garden and the Opera House for charitable performances.22

The emerging bourgeoisie displayed itself according to religious lines during charity performances in the Opera House, al-Azbakiyya, and in the Zizinia theater in Alexandria—though these lines could also be crossed. As discussed in chapter 6, the cooperation with charitable societies for Arabic theater troupes was often crucial in order to gain more visibility and a larger audience. This included a few cross-sectarian interactions. In 1885, the Muslim singer ʿAbduh al-Ḥamūlī was asked by the Greek Catholics’ Charitable Society to contribute to a charity evening in the Opera House.23 However, finally, instead of ʿAbduh, the troupe of Yūsuf Khayyāṭ performed the play al-Ẓalūm (The Tyrant) starring another Egyptian Muslim singer, Salāma Ḥijāzī, who “won a complete victory over the hearts” of the audience.24 ʿAbduh al-Ḥamūlī sang in Alexandria for the benefit of Jamʿiyyat al-Tawfīq al-Khayriyya in 1886.25 One year later, he repeated this in the Cairo Opera House for the benefit of the Free Jewish Schools (al-Madāris al-Isrāʾīliyya al-Majāniyya, Écoles Gratuites Israélites du Caire), and al-Ahrām, run by Christian Arabs, thanked his benevolence.26 These instances have often been considered as proofs of liberal cosmopolitanism or nationalist unity. However, the occasions are rare, and served class socialization.

Theatrical Societies and Charity

The self-educative aspect of the intersection of charity and theater must be also highlighted. Najm enumerates dozens of “theater societies” (jamʿiyyāt al-tamthīl) from the 1880s until World War One.27 These were clubs and groups of men (and perhaps women) who did not earn their living as actors but considered theater an important passion or social duty. The earliest, the Society of Refined Education (Jamʿiyyat al-Maʿārif al-Adabiyya), was established in 1885 by officials of the Train and of the Post Companies and lasted until 1908. It had the explicit aim of bringing “Egyptian taste” into theater as opposed to the taste of Europeans and Syrians. In the 1890s dozens of such amateur, often ephemeral, theatrical associations were established: Jamʿiyyat al-Ibtihāj al-Adabī (1894), Jamʿiyyat al-Taraqqī al-Adabī (1894), Jamʿiyyat al-Sirāj al-Munīr (1895), Jamʿiyyat al-Ittifāq (1896), Jamʿiyyat Nuzhat al-ʿĀʾilāt (1897), Jamʿiyyat Muḥibbī al-Tamthīl (1899), and so on.28 These amateur clubs and groups entertained relations with the more influential charitable societies. Most important, the society-troupes represented a middle-class form of engagement with self-refinement and solidarity, somewhat independent from the large landowner elite and zevat aristocracy.

Prices and Salaries

It is time to talk money. The acquisition of cultural capital is typically conditioned by economic factors and by transmission. The economic factors in the case of theater performances can be measured through the ticket prices. The Opera House was described by English journals as the space of “the richer classes” in December 1882.29 The writer Tawfīq al-Ḥakīm quotes in a semifictional note an actor who started his career in 1882 and who “remembers” that at the time the ticket was only 1 piaster for an ordinary performance but for a Qardāḥī-Ḥijāzī performance in the Opera the cheapest was 4 piaster so they could watch it only once!30 Who had the money to watch a play in the theater? And who had the clothes to attend the Opera?

In its first years, the entrance fee to khedivial theaters, for simple seats, was indeed expensive for the ordinary. In 1869 the cheapest ticket for a third floor seat in the opera was two francs (around 8 piasters), but the first floor best loges cost 75 French francs.31 In December 1869, the best places in the Cirque were five francs, three for the second rank and one and a half francs for the cheapest seats.32 Yet despite the cheap tickets, the expenses were not calculated for the income at the gate: Draneht’s system, as we have seen, always operated at a deficit.

Compare the 1869 prices with the salary of Aḥmad al-Kūmī, the farrāsh of the Opera House. In the middle of the financial crisis, in 1877 he earned monthly 38.88 francs (149 piasters), as shown in table 3.1. Al-Kūmī, a man who received relatively low pay, could visit the Circus by spending approximately one day’s salary on the cheapest ticket or two days’ salary for the cheapest ticket in the Opera (provided, of course, that he already owned the appropriate clothes). If he ever wanted to rent the best loge in the Opera, he would have had to spend two months’ salary for a single evening. (However, since he was the farrāsh of the Opera he could watch the plays for free.)

Yet in fact, al-Kūmī’s salary in 1877 was still double that of the average worker’s wage. The average daily wage of an unskilled worker or peasant was two piasters (the price of a load of bread, approximately 0.5 franc), that is, monthly around 60 piasters (around 15 francs). Given this, one can also measure the significance of the amounts donated by some pashas to the French and Italian artists. For instance, in 1870 for the caisse des secours of the actors Ali Pasha Şerif donated 505.5 francs, Sefer Pasha 500 and “La Princesse Said Pacha” 757.50 francs.33 This last donation is almost twenty times more in one sum than al-Kūmī’s monthly salary, and more than forty times more than an unskilled worker’s monthly pay. The favorite musician of Khedive Ismail, ʿAbduh al-Ḥamūlī, is said to have received the handsome 15 LE (375 francs) and Almāẓ 10 LE (250 francs) monthly salaries in the 1870s.34 It is worth remembering that the Private Domains paid 320,000 francs alone for Aida’s production in 1871, an almost unimaginable sum compared to the salary of workers and even bureaucrats in the khedivate.

Later theater, even the Opera House, became more accessible. In the 1880s–1890s the Egyptian pound was relatively stable, fluctuating around 25–26 francs. One franc was 4 piasters. In the spring of 1882, the impresario Paravey calculated 180 LE (4680 francs) for the whole season and 4 LE (104 francs) per performance for a first-class box; 65 LE (1690 francs) for a second class box and 2 LE (52 francs) per performance; and a simple seat’s annual subscription 20 LE (520 francs) and 8 francs [!] per evening; and in the amphitheater 2.5 francs per evening without subscription.35 Compare this with Saʿd Zaghlūl’s salary of 8 LE (208 francs) monthly as the assistant editor of the official bulletin in 1881.36 He could easily watch the Ḥijāzī-Qardāḥī performances, which were presumably cheaper, in the ʿUrābist spring of 1882.

Ryzova quotes that the young ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz Fahmī in 1889 was very happy to be appointed in a job with 8–12 LE (208–312 francs) monthly salary, since the average was 5 LE (130 francs). She adds that in the early 1900s, a rural household of five lived on 3 LE (78 francs) monthly. Two feddan of land could yield 25–30 LE (650–780 francs) yearly, approximately 2 LE (52 francs) monthly.37 The high officials of the government earned comparatively generous amounts: for example, Yūsuf Shakūr was appointed the head of the Alexandria municipality council in 1892 with 100 LE (2500 francs) monthly;38 while Fayzi Pasha was appointed governor of the Gharbiyya province with 125 LE (3125 francs) monthly salary in 1893.39 One must note again that ʿAbduh al-Ḥamūlī is said to have received yearly 180 LE from Khedive Tevfik, too, in the 1880s.40 It was good to be an Ottoman Arab star.

The young Ismāʿīl Ṣidqī (1875–1950; prime minister in the interwar period) earned only 5 LE (130 francs) monthly in 1894 and envied his friend ʿAbd al-Khāliq Tharwat, who was one year ahead, earning 15 LE (390 francs) at the same time.41 Ismāʿīl Ṣidqī would have had to spend almost his whole monthly salary for a first-class box in the Opera House for one evening, but he could have regular access to a simple seat if he wished so and had the proper clothes. He could participate, and likely did so, in the patriotic charity occasions of the Islamic Charitable Society in the late 1890s, which asked 10 piasters (0.1 LE, 2.5 francs) for the ticket in al-Azbakiyya Garden but 50 piasters (0.5 LE, 12.5 francs) for an ordinary seat in a charity evening in the Opera House and finally 5 LE (the entry-level monthly salary of bureaucrats) for a first-class box!42

Comparatively, in 1895 in the private Abbas Hilmi Theatre in Alexandria (it was called khedivial, but it was a business enterprise) tickets for an Italian production were the following: the best box was 1 LE (100 piasters, 25 francs this time) for one performance, which included the entry of three individuals, a numbered seat went for 8 piasters, and a simple entry was 5 piasters.43 Compare this with the 292.20 piaster monthly salary of Saʿd Zaghlūl’s cook in 1901.44

Based on this data, there were hierarchies between theater buildings, performances, and within the theater itself. Access varied according to income. A simple seat for an ordinary performance in a private theater in the 1880s–1890s was affordable for bureaucrats, small merchants, teachers, or even for a cook in fin-de-siècle Egypt. A middle-income bureaucrat could join the audience by buying simple seats even in the Opera House—if he had the proper clothes. Sartorial politics and interest, however, were possibly defined by the family background. Ṣidqī, for instance, came from an assimilated, elite Turco-Egyptian family in government service, and thus possibly had a suit as part of his social background. In general, the above data means that the Arabic reports we have followed about performances in the Opera reflect the experience, emotions, and ideology of the wealthier segments of Egyptian society.

Language and Moral Distinction: The Educated Nation

Language also became a marker of distinction and a central characteristic of the patriotic idea of community. I have already argued that public patriotism had to occur in fuṣḥā Arabic because of its historical depth and because of the difference between Syrian-Egyptian vernaculars. The space of the theater and the opera house in particular helped to transform the earlier mode of addressing the ruler into a new mode of speech, still in Arabic, but this time addressing the imagined community. There seems to have been an understanding among educated Arab intellectuals that only those who know fuṣḥā Arabic could speak in the name of the nation (umma). Language use further emphasized the distinction between poor and not poor in cultural terms.

However, this distinction was not clear cut. I have already tackled the question of language in plays and poetry. With the exception of Sanua and Jalāl, we have seen a preference for fuṣḥā Arabic in plays (Nadīm uses ʿāmmiyya for characterization). Naqqāsh, Khayyāṭ, Qardāḥī, and al-Qabbānī in the 1880s and 1890s mostly staged or composed fuṣḥā plays in which ʿāmmiyya was often used for articulating humorous situations. A particular example in chapter 6 was the play Hārūn al-Rashīd by Maḥmūd Wāṣif, staged by Qardāḥī’s troupe. Intellectuals such as the writer Muḥammad ʿUmar, and the journalist and politician Muṣṭafā Kāmil, also preferred fuṣḥā in public speech.45

Wafā Muḥammad, the guardian of books in the Khedivial Library, published his opinion about the vernacular and fuṣḥā Arabic in 1892. He emphasized that the ordinary speaker had no conscious knowledge about language but that educated speakers were special because “only they can be called rightly by the name ‘nation’ (umma) [because their] books are written in the fuṣḥā language in which there is no distinction between Muslim and Christian, only between Eastern and Western [ways of writing].”46 It was no surprise that he considered “the unity of language . . . a condition for the unity of the nation” and asserted that “the speakers of Arabic in all territories are all possessors of the same connection: the Arabic language.”47 According to Wafā Efendi, the young khedive Abbas Hilmi II was especially intent on teaching fuṣḥā in Egyptian schools.48 This employee connected educated Arabic to dynastic praise and patriotic (here: pan-Arab) unity. We may also note that in 1892 an Academy of Arabic Language (Mujtamaʿ/Majmaʿ al-Lugha al-ʿArabiyya) was established in Egypt—a development that did not please every Egyptian.49 It was also in these years that patriots such as the young Muḥammad Farīd remarked that the use of French in official occasions should be replaced by “the noble Arabic language.”50

The use of language in theater developed into an expression of social distinction. An example is the writer and actor Faraḥ Anṭūn (1874–1922), yet another fervent Ottomanist from Beirut. His play New and Old Egypt was accompanied by an explanation about the play itself and about “the problem of language.” The problem was the language registers, and the fact that fuṣḥā was not used in everyday exchange. Anṭūn believed that one had to use fuṣḥā Arabic if the play was a translated one, because the original language in which the characters spoke was foreign (aʿjamiyya). The problem of register arose when the play was in Arabic and related events and activities that in life happened in ʿāmmiyya. What would the audience think, asks Anṭūn with horror, if “they would hear the ladies of dancing cafes, the [street] sellers of the newspapers, the female and male servants, the Nubians (barābira), the drunken and the negligent or even the ladies in their private rooms talk in fuṣḥā?” But if the author would use ʿāmmiyya in general he would commit an even more horrible mistake, namely, that of weakening pure Arabic, thus harming “those who tasted the pleasure of this language.” His solution was that the elite characters should talk in fuṣḥā, because their education made doing so their “right” (ḥaqq), while the ordinary characters would talk in ʿāmmiyya. In order to avoid situations in which one person might ask in fuṣḥā and the other answers in ʿāmmiyya he sometimes allowed elite characters to talk in ʿāmmiyya, even a pasha.51 But the socially inferior would never use fuṣḥā. Such social valorisation of language here was a literary trick but mirrored the deeper relationship between fuṣḥā and power.

In addition, language is a complex operation of somatic communication, especially in the theater. For instance, Qardāḥī once performed the role of Othello with an Italian company in Alexandria and while they spoke Italian, he “embodied the role in an Arabic way” (yumaththil tamthīlān ʿarabiyyān) on stage.52 This might have meant his use of the Arabic language or a somatic movement characteristic of Arab actors or simply that he was regarded as an “Arab.”

ELITES AND PUBLIC ENTERTAINMENT AS HONORABLE

Ryzova points out that between the wars middle-class Egyptian families held up their respectability by enjoying entertainment in private.53 The valorization of leisure, however, occurred with the opposite value among the wealthy. Being publicly entertained in official spaces became in itself a social marker of distinction. This change transpired through an interplay between cultural, gender, and economic codes. Being publically entertained and being an elite male individual were connected. In khedivial theaters, there was also the sense that through sheer bodily presence Ottoman Egyptian dignitaries were displaying sovereignty.

In the early period of khedivial culture Ismail financed a number of loges through al-Dāʾira al-Khāṣṣa, both in the Opera and in the Comédie for the members of his entourage (in French Suite de Son Altesse). However, not everyone’s seat was covered automatically. For instance, Ismail’s son “Prince” Hüseyin did not pay for his loge in December 1869, and Draneht had to ask for the payment from the Private Domains. There is no information revealing whether the “princesses” of the harem ever paid for their special loges. For instance, in the contract with Meynadier in 1871, the boxes of the khedive and his harem were included free of charge in the Comédie. Thus, in the 1870s a number of Ottoman Egyptian dignitaries attended the theaters in Cairo, because it was free for them, and, possibly, because they were interested.54

The children of elite families were certainly interested. The khedivial children as early as in 1870 were brought to the Circus with the female members of the harem by Zurayb Bey, the doctor of Ismail.55 Aḥmad Shafīq (Ahmed Şefik), an important member of Abbas Hilmi II’s court, recollected that his brother and the schoolmates were desperate to attend the performances in the Opera during Ismail’s reign. They employed a trick. They bought two tickets, and two of them entered the building. Then one came out with the two tickets and two again entered and so on. Their passion may also have been fueled by the fact that every year Ismail sent free tickets to the best student group in that school.56 This anecdote evokes again the idea of “internal Europe” in Egypt and alludes to the fact that the acquisition of high European culture started in childhood for the new elite generation within Egypt before they studied in France or England.

An anecdote underscores that the Opera House became very important—arguably even ridiculously important—for the “princes” of the ruling dynasty. Mehmed Ali, the younger brother of Abbas Hilmi II, and his uncle Fuad (the later King Fuad) initially shared a box in the 1890s. Only Mehmed Ali used it because Fuad gave up his share. In 1897 Mehmed Ali failed to respond to inquiries regarding whether he wanted to keep the box, therefore, Fuad was given full ownership. Mehmed Ali became furious and, though apologies were made, he decided he now wanted a box of his own.57 A box at the Opera was by this time understood as a prime space for practicing one’s modernizing habitus and was included in the symbolic hierarchy of elite honor.

We have seen examples of educated Arabic- and Turkish-speakers who celebrated the theater as an appropriate public space. Amīn Fikrī (son of ʿAbd Allāh Fikrī), for instance, during his visit to the Orientalist Congress in Stockholm in 1889 found nothing objectionable at a reception about the dancers of the Swedish Opera in Egyptian costumes.58 In 1896, the young Muṣṭafā Kāmil gave his first political speech in Arabic in the Abbas Theatre in Alexandria to an audience of eight hundred people, including some Egyptian notables (aʿyān).59 The theater building served as a space that staged him as a public figure.

There were less dignifying venues such as the Garden Theatre in al-Azbakiyya, which nonetheless counted as proper for khedivial representation. On the occasion of the performances by an Ottoman Armenian troupe in 1885, the Turkish-speaking ladies of Cairo attended this small theater; at their head was Madame Nubar—and Khedive Tevfik.60 There were also charity balls held in al-Azbakiyya. Sometimes, such as in 1895, the famous Egyptian singers ʿAbduh al-Ḥamūlī, Muḥmmad ʿUthmān, and Sheikh Yūsuf sang together for the attendees, including the khedivial family, ministers, and Lord and Lady Cromer.61 The Garden Theatre was also important to governmental employees. In 1897 ʿAbd al-Karīm Mūsā, an employee at the Ministry of Public Works, complained that he did not receive the free place there that was granted to the staff of the ministry. He was seated in a first-class chair, but he had to move to a less prestigious seat, and so after the first part of the play he left in anger.62 This example shows that employees in lesser positions also thought that they had a right to free seats in theaters owned by the government.

Private theaters also served as spaces of elite entertainment. In Alexandria, the Zizinia Theatre from its inception served as an embodiment of (resident Italian, Greek, French, later Syrian) bourgeois wealth and power. Here rulers and statesmen also regularly appeared, and the khedive had his own box. We have seen that between 1879 and 1882 Tevfik participated in Arabic performances in this private theater. In the 1880s, the prefect of the city and the Cairo-based pashas on holiday also attended performances. Zülfikar Pasha, for instance, in 1888 supported the charity organization of the Roman Catholics by attending a performance in the Zizinia.63 In 1896, Ismāʿīl Ṣabrī attended the Greek community’s evening in the Zizinia, occupying the loge of the khedive.64 Muṣṭafā Kāmil, as noted, entered the public sphere physically in this building.

Entertainment as Dishonorable—and the Military Occupation

Stages that served a purely commercial function, such as café-chantants, revues, and cabarets, were criticized through a specific moral (and gendered) discourse from the 1890s. There were voices that government-financed spaces were also immoral. In the already quoted novel of Muḥammad al-Muwayliḥī the resurrected character, Ahmed Pasha al-Manakli, becomes angry upon seeing the statute of Ibrahim (once his friend and military leader) in front of the Opera House. His companion, ʿĪsā ibn Hishām comments that the Opera “does more harm than good.”65

The discourses of dishonor, however, rarely crossed into official territory. There are no instances of ballet performances in the Opera House being criticized, for example, even though there was frequent criticism of dancing girls in bars around al-Azbakiyya. The café chantants in the neighborhood offered roulette games where Egyptians spent, and too often lost, their money as early as the 1870s.66 As discussed in chapter 7, immoral dancing in cafes was prohibited in the early 1890s. Musicians cursed the music halls as “caves of demons,” and al-Azbakiyya itself was decried as a “square of debauchery and immorality.”67

The British military occupation facilitated the opening of shops with alcohol licenses and the creation of more entertainment spaces for soldiers in the 1880s. There were special theaters to entertain British soldiers. The main space in Cairo, apart from the Club, was the Azbakiyya Garden where a British military band performed in the afternoons. Several plays in English or French were staged during the late 1880s and 1890s, often in temporary army theaters; there was even one in the Citadel. Officers frequented al-Azbakiyya, but were apparently quite loud (for instance, in June 1886 British military music was forbidden here for a period, out of respect for the death of Hoşyar Hanım).68 Another private theater that the British officers often visited was a Politeama building in Cairo, where General Stephenson was celebrated once.69 In general, they—together with some Egyptian army officers—drank and looked for women in the new pubs and cafes around al-Azbakiyya.70

OCCUPIERS AND OTTOMANS IN THE KHEDIVIAL OPERA HOUSE

The game of empires served as the backdrop for Cairo high society in the 1880s. Since the doctrine of the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire and the costs of occupation pushed the British towards early evacuation, a new agreement was planned. In 1885 an Ottoman-British agreement specified that two high commissioners should be sent to Egypt as direct representatives of both governments, in addition to de facto rulers: the British consul-general and the khedive. From the British side Sir Henry Drummond Wolff (1830–1908) and from the Ottoman side Gazi Ahmed Muhtar Pasha (1839–1919) were chosen. Their task was to negotiate the evacuation and the future size of the Egyptian army. This goal was never achieved. Among the reasons for the failure were the unstable British politics, changing public opinion, Baring’s opposition, and the Mahdi’s revolt in the Sudan.71 Wolff was recalled in 1887, but Muhtar Pasha remained in Egypt for two decades.72

This was the political context for the revival of elite patriotism, as we have seen in chapter 6. After surveying distinction based on economic and social capital, let us now focus on the way politics and distinction were connected in the main, symbolic khedivial space: the Khedivial Opera House.

Occupiers and Subscribers

Special evenings were arranged for the senior army officers and members of the British resident community, for instance, in April 1884 in the Opera House.73 The colonial administrators, however, in general were not fond of opera performances. George Boyle, one of the British administrators who spent the longest time in colonial Egypt, wrote to his mother in 1904 that he went to the Opera, “a thing I seldom do.”74 A senior military officer, Lord Cecil, described the opera as “nothing else on Earth except a concert of cats.”75 Nonetheless, Cromer had to attend performances, even the Arabic ones, to counterbalance the presence of the khedive. (Naturally, Cromer and his wife also gave “almost weekly parties” at the embassy for their own British community.)76 Wolff, the British High Commissioner, regularly attended the Opera House while in Cairo, and an American diplomat also loved to go to the Opera at the end of the 1890s.77 In this way, the Khedivial Opera House served as an unofficial space for imperial diplomacy, too. How can we define the wealthy and official audience in the 1880s and 1890s?

The government provided a definition. In 1886 they wanted to suppress the sponsorship of the winter seasons. They expected that individuals who were described as “a class” of foreigners economically “benefitting directly from their stay in Cairo” should provide at least half of the expenses for bringing foreign troupes.78 The definition of a “class” of “those who profit directly from their stay in Cairo” can be further qualified by a subscription list from the same year, 1886, as given in table 8.1.

The 230 names were registered by the impresarios to support their request for the next season’s concession in 1886–1887, and this purpose must be taken into consideration. These names comprise the core of what we might think of as the myth of a cosmopolitan elite in Cairo. It includes individuals whose profession could be regarded as elite at the time: diplomats, bankers, senior military officers, lawyers, doctors, and directors of companies. Mostly Italian, French, British, Greek, and few local (such as the Qaṭṭāwīs) names figure in the list. Notable are the Russian consuls at the very end (who may have been added in haste). Names such as Izzet Bey, Camougli, Farrag Bey, A. Nassif, Moussally allude to individuals of Ottoman background who were interested in Italian opera. The list includes men of distinction, and perhaps men who wanted to be seen as such. Despite the fact that these are all male names, it is more likely that whole families rented boxes. Since Sir Wolff, the British Imperial Commissioner, headed the list, let us turn now to his operatic counterbalance, the Ottoman representative Ahmed Muhtar Pasha.

Ottomans and the Arabic Theater in the Opera

The Khedivial Opera House was instrumental for proclaiming Ottoman sovereignty in the late 1880s. This was an unexpected function given, as we may recall from chapter 3, that the theaters were constructed to hide the Ottoman face of khedivial Egypt.

Ahmed Muhtar arrived in Cairo in December 1885. The Ottoman Imperial High Commissioner was a remarkable man. A warrior and general of the Ottoman army, he fought the Russian army in 1877–1878 (hence the title Gazi). The presence of an Ottoman war hero aroused pro-Ottoman sentiments in British-occupied Cairo.79 Muhtar was also a man of science, interested in time-keeping. He published a piece in Turkish on this theme immediately after his arrival in Cairo,80 and also a Turkish-Arabic bilingual book (the Arabic translation was done by Şefik Mansur Yeğen, the nephew of the khedive).81 It was well received among the local intelligentsia, who seem to have used the publication to introduce Ahmed Muhtar to the Egyptian elite.82 In the light of On Barak’s analysis of the general transformation of temporality in Egypt, it is remarkable that an Ottoman general was so concerned with time and periodization.83 As the representative of the sultan, the liege-lord of the khedive, Muhtar lived in one of the most beautiful palaces, the Ismailiyya Palace. He also married his son to Khedive Ismail’s youngest daughter, thus properly joining to the Ottoman Egyptian zevat.84

In occupied Egypt, the Ottoman Empire now provided the framework for patriotism in Arabic. Ahmed Muhtar faithfully upheld the Ottoman colors in Cairo, despite having only symbolic means, secret agents, and his own bodily presence to express Ottoman sovereignty. For instance, his presence forced the khedive to celebrate the Cülus-i Hümayun (the anniversary of the sultan’s accession to the throne).85 The symbolism was displayed in the Khedivial Opera House too: soon after Muhtar’s arrival the first proper Arabic season in the Opera by Qardāḥī-Ḥijāzī’s Arab Patriotic Troupe offered a convenient moment to start a symbolic competition with Sir Wolff. Al-Ahrām and other Arabic journals took up a pro-Ottoman position this time. Muhtar Pasha subscribed to all performances of Qardāḥī’s troupe and promised his personal attendance. This was made an example by al-Ahrām, and, as usual, the notables (zevat and aʿyān) were summoned to support Arabic theater.86

Ottoman Egyptian notables attended the performances with Muhtar often. For instance, on 16 March 1886 the khedive, his harem, Osman Galib, together with Muhtar and Wolff, attended the performance of Ḥifẓ al-Widād.87 A few days later, the khedive and Khayri Pasha, the old supporter of Arabic theater, with Muhtar and Wolf watched together Wāṣif’s Hārūn al-Rashīd.88 Tevfik, as we have seen, encouraged Qardāḥī to apply for the next year’s concession, and Muhtar requested the repetition of the whole performance. He liked Hārūn al-Rashīd,89 possibly because the character of the caliph could be read as an allegory of the sultan-caliph. Al-Ahrām announced later that this play would be repeated due to “popular demand.”90

In an occupied land, Muhtar’s role was to represent the continued protection of the Ottoman Empire for its subjects. He had a special relationship with the Ottoman subjects in Egypt. In particular, the Syrian Maronites often asked him to be the patron of their charity evenings. In this way, for instance, in 8 March 1887 under his patronage ʿĀyida was performed in Arabic in the Opera for the benefit of the Maronite community.91 This evening was considered to be a celebration, of course, in honor of Sultan Abdülhamid II.92 Similarly, in the last triumphant season of Qardāḥī and Ḥijāzī in the Opera House in 1889, it was under Muhtar’s auspices that the Maronite Charitable Society organized a charity evening. On this particular night, the secretary of the Society gave two speeches: the first praised the sultan and identified the Maronites in Egypt as Ottomans (ʿuthmāniyyūn) while the second paid tribute to the khedive.93 In this very subtle way Muhtar Pasha was able to radiate the authority of the Ottoman Empire upon its subjects in occupied Egypt.

Muhtar’s relationship with Abbas Hilmi II was complicated. Abdülhamid II demanded the acknowledgment of full Ottoman suzerainty in Egypt and his rights as the caliph of all Muslims; this entailed an almost compulsory yearly visit by Abbas Hilmi II to Istanbul.94 At first, Abbas happily made this visit since the Ottoman umbrella was useful to rebond Egyptian loyalty in the 1890s as we shall see below. Also, Muhtar posed as a respectable fatherly figure to the young khedive, playing an instrumental role in his appointment ceremony, and generally masterminding a surge of Ottomanism.95 In the mid-1890s Abbas and Muhtar often attended Muslim ceremonies and opera performances together. Nonetheless, Abbas wrote in his memoirs that he thought that “it is necessary to handle him [Muhtar] with care.”96 Their goals against the British were connected but Muhtar, a devoted man of the Ottoman Empire, attempted to curb khedivial authority.

ARABIZING THE KHEDIVE 2.0: MUṢṬAFĀ KĀMIL AND THE PATRIOTIC IMAGINATION

Ottoman Arab patriotism reached its peak during the first years of Abbas Hilmi II’s reign. The best example of this ideological and emotional peak is the early thought of Muṣṭafā Kāmil. For the first time, the racial definition of the community appeared also among religious, linguistic, and imagined territorial concepts. In this final section, I explore Kāmil’s student years in the late 1880s—at the moment of the restoration of khedivial authority by old Egyptian intellectuals, his early relationship to Abbas Hilmi II, and his drama The Conquest of Andalusia (Fatḥ al-Andalus, 1893). This play exemplifies the emergence of an imagined form of patriotic unity with a strong (pan-)Arab favor, reconfiguring yet again the khedive as Ottoman representative.

Kāmil’s Posthumous Image

It is not easy to gain access to a “historical” figure in history. In the same way that royalist historians formulated the image of Khedive Ismail as a magnificent modernizer, the nationalist counterstroke created Muṣṭafā Kāmil as the heroic model of the patriotic Egyptian man rising against the old regime. Already in the interwar period, fathers were consciously forming their sons according to Kāmil’s life narrative.97 This model of the ideal efendi included knowledge of good Arabic and good French, education in the law school, the pilgrimage to Europe (Paris), and early signs of being a genius. The social value of “youth” was also the result of this model.98

The first codifier of Kāmil’s image as part of the national pantheon was Kāmil’s older brother, ʿAlī Fahmī Kāmil (1870–1926). He published nine volumes of collected writings with recollections and photographs with the narrative of “the great man,” soon after his younger brother’s death.99 Next, the historian al-Rāfiʿī contextualized this image in the 1930s within nationalist teleology, framing Kāmil as the “one who resurrected the national movement.”100 The extent to which Muṣṭafā Kāmil was tied to khedivial culture as a member of a wealthy Egyptian family and his early years as a dynastic patriot were suppressed. Equally suppressed was the function of Abbas Hilmi II and his old supporters, such as Riyaz, ʿAlī Mubārak, or even ʿAbd Allāh Nadīm, in generating a new wave of patriotism, thus leaving only Kāmil as the dynamic center of change.

For al-Rāfiʿī, it was crucial to prove that Muṣṭafā Kāmil started his patriotic activity prior to Abbas Hilmi II’s reign. Chronology was important to ensure that “national history” and “political (dynastic) history” were two separate narratives101 and to discredit any claim the khedive might have had in launching, or having a share in, the politically organized national movement. Abbas Hilmi II, to his credit, did not claim that Kāmil was his creation; he writes in his memoirs that “Mustafa Kamel belonged to no one but himself.”102 The following sections investigate the relationship between the old elites, the young khedive, and the young intellectual.

The Mosque and the Opera: The Peak of Patriotism

Abbas Hilmi was studying in the Theresianum in Vienna when his father Tevfik unexpectedly died in January 1892. The death spurred a certain amount of chaos, as the death of an Ottoman vali always did in Egypt. And now there was the British occupation. At first, Abbas assumed governing powers without an Ottoman firman (there was only a telegram from Abdülhamid II acknowledging his rights). There was, for the first time, a border issue connected to his appointment as khedive.

The solution that emerged called on multiple sources of support. First, there was the Egyptian army. In this moment of transition, an unprecedented event occurred: the army—including both the Egyptian and the British officers—took an oath of allegiance to the new ruler in his presence on January 26, 1892. The Egyptian officers did so in Arabic, swearing on a copy of the Koran (which was in the hand of the Sheikh al-Azhar), and on their own honor, that they would obey the khedive and “defend the rights of the country.”103 After this, it seems logical that Abbas Hilmi II changed his personal guards from English to Egyptian soldiers.104

Next came Ottoman recognition and an appeal to Egyptian patriots. After a long delay, he received the firman. On British insistence, the ceremony took place in a new environment, at Abdin square, rather than in the Citadel, making it a public event.105 Then the khedive and his men consciously prepared a new beginning. He ordered a decrease in the price of salt and pardoned prisoners. He organized dinners with Alexandrian notables. Next, in the autumn of 1892, he declared general amnesty for the remaining ʿUrābists, including ʿAbd Allāh Nadīm, excluding only ʿUrābī and his fellow exiles in Ceylon. Nadīm called him “Abbas, the Compassionate.”106 It seemed that patriotic elites and the khedive were ready for a new compromise, yet again.

The result was a peak in Arab patriotism as related to the khedive. “Our prince” was described by the intellectual Aḥmad Zakī as “the best model and the perfect ideal, because he is the first in engaging with the advancement of the beloved homeland to the peak of pride and the tribune of honour.”107 This warm welcome should be understood in light of the ongoing restoration of the khedivate since the late 1880s, the amnesties, and new appointments (Aḥmad Zakī himself was promoted in 1892).108

The symbolic test of restored trust was a political clash, which, although it resulted in the defeat of Abbas Hilmi II, in fact brought him a magnificent victory in the public sphere. The khedive clashed with Consul-General Baring over the discharge of Prime Minister Mustafa Fahmi in January 1893; Abbas appointed a new government, but Baring forced him to change it: the negotiated result was the return of Mustafa Riyaz as prime minister. The khedive received support and thanks from even countryside ʿumad and aʿyān, who seem to have hated Mustafa Fahmi.109 In Shārūbīm’s description, when the khedive prayed in the al-Ḥusayn mosque one Friday in early 1893, the crowd wanted to pull his carriage instead of the horses, and during this celebration a young Copt gave an effusive speech.110 The people of Cairo shouted, “Viva the prince, down with the occupiers!” As quoted at the beginning of the chapter, and in the beginning of this part, he then went to the Opera for a performance, where the audience celebrated his presence.111

The peak in popularity in the first years of Abbas’s reign can be corroborated from a number of other sources. The demonstration of sympathy in January 1893, when, by the way, the khedive watched Aida in the Opera, is remarked upon also by Muḥammad Farīd.112 He further gives an account of Abbas’ tour in Upper Egypt, during which cities were elaborately decorated in order to celebrate the khedive (this was, admittedly, a standard way of expressing loyalty that was also enacted for his less popular ancestors). The young khedive (or perhaps more likely, his advisors), effectively deployed both traditional and nontraditional symbols in his first years. Abbas Hilmi II regularly went to the mosque to pray publically and also attended the Opera House. In fact, sometimes these were connected. Consider this piece of news from 1895:

H.H. the Khedive visited the Citadel Mosque on Tuesday evening to attend the ceremonies on the anniversary of “Leylat el Mearag” [!], or the night of the Prophet’s miraculous ascent to heaven . . . Ghazee Moukhtar Pasha, with a great number of high functionaries, assisted at the proceedings, and a large number of tourists were also present. His Highness left about nine o’clock and drove to the Khedivial Opera House, when Donizetti’s Favorita was performed.113

A few weeks after this occasion, during Ramadan, the khedive went to break the fast with the ʿulamāʾ and then similarly attended the opera Le Petit Duc in the Khedivial Opera House.114 Abbas Hilmi II resorted to the simultaneous use of religious and nonreligious symbols. The presence of the British occupiers helped to stage him as the representative of both the Muslim-Ottoman and the national community in the face of foreign intrusion, while his young age boosted popular sympathy.

Elite Anti-Abbasism

This popularity rested on the restoration of the khedivial image. Old khedivial patriots, such as ʿAlī Mubārak or Mustafa Riyaz, and new Syrian loyalists were instrumental in this restoration. It also relied heavily on the narrative of Mehmed Ali as regenerator of Egypt. Before we see the old men in their relationship with the young khedive and Muṣtafā Kāmil, the differing opinions should be pointed out.

The salon of “Princess” Nazlı (185?–1914), the daughter of the pretender Mustafa Fazıl, in fin-de-siècle Cairo was less than friendly towards the new ruler. This legendary great-aunt of Abbas Hilmi II was a supporter of the ex-ʿUrābists, and may also have been associated with Said Halim, the son of the pretender Abdülhalim in Istanbul. Nazlı, at the center of the dynastic conspiracy, hosted a number of politically active and culturally elitist individuals and handsome British officers. She herself, according to the memoirs of Muḥammad Farīd, “was among the supporters and lovers of the British” and “always wrote against the Egyptians.”115 Members of her wide circle, such as Sheikh Muḥammad ʿAbduh, heavily opposed the Ismailite line and the dynastic historical ideology that located Mehmed Ali in its center as “the founder of modern Egypt,” even at the price of being more friendly to the British occupiers. 116 A few other significant members of the Muslim intelligentia soon clashed with the khedive, such as the leader of Sufi orders, Muḥammad Tawfīq al-Bakrī, who already in 1895 seems to have a major disagreement with the khedive and this cost him his position as the “leader of the Prophet’s descendents” (naqīb al-ashrāf).

The Student and the Prince

Let us now examine patriotism as the imagined Ottoman nation-ness of khedivial Egypt. Muṣṭafā Kāmil, in 1897, addressed a letter to Abbas Hilmi II in which he offered to write a book about “the real reasons of the ʿUrābī revolution,” “guarding jealously the dignity of your name in history.” He addressed the khedive, however, in an entirely new way in Arabic: ḥaḍrat al-sayyid al-jalīl wa-ibn al-waṭan al-ʿazīz which can be translated in at least three different ways into English: “the great lord and son of the homeland, the Mighty One” or “the great lord and mighty son of the homeland” or “the great lord and son of the dear/mighty homeland.”117 The ambiguity of whose adjective goes with al-ʿazīz, regardless of its conscious or unconscious use, indicates the transferability of khedivial attributes to the homeland and vice versa. Be this as it may, Kāmil clearly addresses the khedive as a member of the imagined Egyptian nation.

There is no exact information about the moment the two teenagers met for the first time. As noted earlier, dating Kāmil’s start of politics before the reign of Abbas Hilmi II was a crucial historical tool to write a national history devoid of the monarchical regime after 1952. The khedive visited the Law School in November 1892, as part of a tour that visited all schools, and Muṣṭafā Kāmil was among those who greeted him. 118 This may have been the first time they met in person. Yet I argue that the date is not actually that crucial: whenever Muṣṭafā Kāmil started to think along ideological lines, he publicly imagined the khedive as the first man of the nation, as an Arab prince. And he was prepared for this imagination.

Kāmil’s family background, social networks, education, and skills are all responsible for his strikingly early embedding in the highest political circles. He was born in 1874 into a prestigious local family in Cairo, which drew on both a traditional and a modern (army) education. His father ʿAlī Muḥammad (1816–1887), from a rich Tanta-based merchant family, was educated in the Tora school and in the Khānka camp during Mehmed Ali’s reign. The family bought a house for ʿAlī Muḥammad’s mother next to the Tora school, in order to see her son when she wished. They also arranged for ʿAlī Muḥammad to be able to leave the school whenever he wanted. This unusual freedom reflected their social network and wealth. ʿAlī Muḥammad became a military engineer, was attached to the entourage of Said Pasha in the 1850s, and finally retired from service from the Ministry of Public Works in 1877. He had two wives, seven sons, and two daughters. His second wife Ḥafīẓa—Muṣṭafā’s and ʿAlī Fahmī’s mother—hailed from a family who could trace back their origins to Ḥusayn, the Prophet’s grandson. There is no indication of the family’s involvement in the ʿUrābī-revolution, and later Kāmil accepted its interpretation as a disaster that caused the British occupation. After their father’s death in 1887, Muṣṭafā and ʿAlī Kāmil inherited a large amount of money, as well as much gold and silver jewelry. Relatively rich, the young boys continued to be educated under the guardianship of their eldest brother.119

Muṣṭafā Kāmil started his secondary education in the Khedivial School and when he was around fifteen (1889) he established a student society, Jamʿiyyat al-Ṣalība al-Adabiyya, where he gave speeches every Friday. The young Kāmil’s eloquence in Arabic caught the attention of ʿAlī Mubārak, who was minister of education at this time again, and who personally tested the knowledge of the few students. Mubārak must have personally known Kāmil’s father, too. There are anecdotes that Kāmil became a frequent visitor in Mubārak’s salon. It is possible that even Prime Minister Riyaz Pasha met the young student there.120

Since the pardoned ʿAbd Allāh Fikrī was also a visitor at Mubārak’s salon in the late 1880s, the ideology of these old intellectuals can be explored in Fikrī’s last book published in his lifetime (printed December 1888). It is a short moral manual for Muslim boys. Fikrī starts with useful knowledge: times, calendars, and measures, followed by sections on “Love of God,” “Affection for the Prophets,” the duties of a child to his parents and family, and moral codes of behavior such as speaking softly, not sleeping with other boys, not cursing, and so on. Fikrī finishes the book with a long section on “The Love for the Homeland” (Maḥabbat al-Waṭan), the main message of which is that “your service [to the homeland] is in fact to serve yourself”; he emphasizes that knowledge is the only remedy against absolute rulers, the adverse effects of foreigners’ rule on the people’s rights in the patria, and the importance of cooperation and mutual respect (through the example of bakers). Yet Fikrī also adds that the community needs a ruler (ḥākim) who stops “the strong from oppressing the weak,” provides justice, and organizes the country, “since it is not possible that all people of the homeland would come together.” This idea of just kingship in the late 1880s reflected the earlier ideas during the gentle revolution, partly generated by Fikrī himself at the time. Fikrī likely expressed his ideas in Mubārak’s salon to the student Kāmil (at one point he actually addresses the reader: “thou, celebrated genius boy, al-kāmil”).121 We should not forget either that the orphaned Kāmil may have also found (grand)father-like figures among these old intellectuals.

In addition to Mubārak and Fikrī, the young Kāmil had connections to other pro-khedivial Egyptians. He came into contact with Sheikh ʿAlī al-Laythī, the Sufi court poet of ex-Khedive Ismail. And, after 1892, there was the pardoned ʿAbd Allāh Nadīm who may have become more than simply a pardoned rebel, since he later wrote secret reports to the young khedive from Istanbul.122 The platforms of expression of Nadīm and Kāmil (journalism, societies, oratory, plays) are often compared and evaluated as if Kāmil had learned these from Nadīm.123 Kāmil did establish a journal, al-Madrasa (The School, 18 February 1893—December 1893), which is said to have reached 24,000 subscribers in eight months.124 Journalism probably facilitated his acquaintance with Nadīm, who printed his journal al-Ustādh (The Teacher, from August 1892) in the same printing house (al-Maḥrūsa).125 Nadīm listed Muṣṭafā’s journal among the new Egyptian periodicals in his own organ126 and, as befits the editor of al-Ustādh, may have given advice to the young man for his al-Madrasa. Their relationship would establish a symbolic connection between the first discontents of European intervention and the new patriotic generation.127 Since Nadīm’s historiographical image as the “orator” of the ʿUrābī revolution made him a perfect hero for post-1952 nationalism, Kāmil’s supposed relationship with him was the subject of much more speculation than his likely more decisive informal education among the old khedivial patriots in Mubārak’s salon.

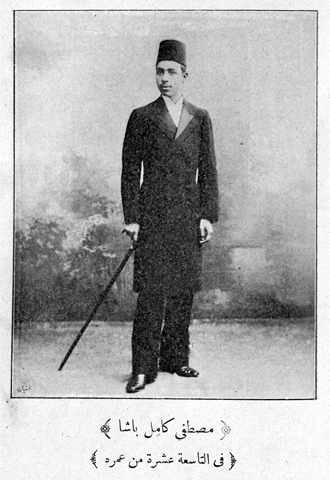

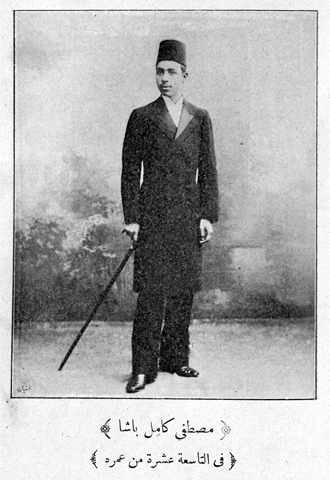

The cooperation between Abbas Hilmi II and Kāmil is first documented in the summer of 1895, but it must have started earlier: possibly Kāmil’s 1894 summer trips and his autumn law exam in France were financed by the khedive.128 By this time, as figure 8.1 shows, young Muṣṭafā Kāmil could dress as a perfect French bourgeois. While Abbas Hilmi II acquired the image of an Arab prince, Kāmil’s acquisition of the dominant modality of European culture as a patriot was complete. He was ready to launch both an international and a national campaign in the name of Egypt, independently of the khedive, but secretly supported by him in the second half of the 1890s. The details of this process, the eventual fallout between the khedive and Kāmil in 1904, the way mass nationalism rose, and the khedive’s changing image belong to another book. Instead, I would like to finish this book by going very close to young Muṣṭafā Kāmil’s world.

ḤUBB AL-WAṬAN MIN AL-ĪMĀN YET AGAIN

The identification of homeland and the khedive was successful in public in 1893. Now the Ottoman khedive was seen as an Arab prince, not delegated by the sultan-caliph to rule Egypt but empowered by the people of Egypt to represent the sultan in Egypt. This interplay of patriotic collective imagination and religious community produced a moment of imaging Muslim power in the early 1890s. There was no clash between religious and patriotic concepts of power yet, because the (reinvented) Ottoman caliphate functioned as the ultimate source of sovereignty.

FIGURE 8.1. Muṣṭafā Kāmil in 1893

Source: Kāmil, ed. MuṣṭafāKāmil, 2: 148.

Kāmil’s first truly significant experience of patriotic solidarity was the demonstration that the school students (headed by the Law School students) organized in January 1893 in favor of Abbas Hilmi II against the British and against their mouthpiece journal al-Muqaṭṭam.129 A generation of educated Egyptians, such as Ismāʿīl Ṣidqī, also name this occasion as their first true experience of patriotic unity. This is also the moment when Abbas was celebrated both in the mosque and in the opera. At this time, Kāmil published his first article in al-Ahrām, entitled “Patriotic Advice” (Naṣīḥa Waṭaniyya), which was a fierce attack on the Syrian supporters of the British. His own journal al-Madrasa regularly published pro-khedivial patriotic poetry, possibly written by Muṣṭafā Kāmil himself. Consider these verses from November 1893, which were published in the “Section of Patriotic Hymns” (Bāb al-Anāshīd al-Waṭaniyya):

You are the sons of the merry Nile / full of pride and great value

Defend it with seriousness / since you built it rightly guided

You are her sons but do not / raise what has been destroyed

The ruler of Egypt is in front of you / our Abbas the strong fortress

This is the Prince in his best / and in his love for his country130

This political song represents an aural imagination in which the homeland and religion intermingle. In my interpretation, the term “prince” (amīr) in this context represents the relationship to the Ottoman caliph. This is also the title that contemporaries, like Shārūbīm, used for Abbas Hilmi II most frequently and, at least in Shārūbīm’s use, it served to reaffirm Egypt’s Ottoman allegiance. The ancient caliphs had emirs who fought on behalf of their empires, and this image was resurrected in the 1890s and applied to Abbas Hilmi II.

It is also possible to interpret this moment in 1893 as transferring the Hamidian ideology of the reinvented caliphate for internal Egyptian politics.131 Muhtar Pasha’s presence in the late 1880s had already enforced the sense of symbolic Ottoman authority; he increased his activity in 1892, and then, in the summer of 1893 the khedive, accompanied by scores of Egyptian ʿulamāʾ and notables, traveled to Istanbul to request (in vain) an Ottoman army contingent to come to Egypt.132 When they returned in August 1893, the welcoming crowd in Alexandria, according to Shārūbīm’s account, sent the message to the British that “the country that you occupy is Ottoman and its prince still belongs to the Ottoman throne.”133 The editor, Sheikh ʿAlī Yūsuf, updated readers about the visit in Istanbul throughout the summer, emphasizing in particular the ceremonial receptions, the friendly welcome of the sultan at Yıldız Palace, and the special dinner in honor of the Egyptian delegation, where all notables were invited.134 Abbas Hilmi II was called emir and khedive, and Abdülhamid II caliph and “commander of the faithful.” The sultan even sent his own band to entertain the young khedive.135 Abbas also met the Abdülhalim and Fazıl branches of the dynasty, and his grandfather, Ismail, all of whom were living in exile in Istanbul.136 Yūsuf later published the articles in a book, which was introduced by a modified version of the slogan “the love of the homeland is part of faith,”137 the familiar patriotic slogan, and sent the book to thousands of al-Muʾayyad subscribers. Being young and having more Ottoman colors, the title “prince” (amīr) emphasized belonging to the reinvented Ottoman caliphate.

Egypt in Andalusia

The romanticized image of Abbas Hilmi II is reflected in Muṣṭafā Kāmil’s drama The Conquest of Andalusia. He was not the only Egyptian to write a political play as a young man; Salāma Mūsa remembers that he too wrote a play as a teenager.138 Egyptians joined the ranks of Arab playwrights: Maḥmūd Wāṣif, Ismāʿīl ʿĀṣim, and many others wrote original Arabic plays in the 1890s. For Kāmil, the Ottoman Arab patriot, theater remained important throughout his life. Even in the first issues of his political journal, al-Liwāʾ, in 1900 he wrote about theater as producing refinement and moral progress.139

The young Kāmil wrote the drama “in the manner” of a Belgian journalist who composed a play about the Belgian revolt against the Netherlands.140 The incentive for writing can be also attributed to the previously surveyed patriotic atmosphere in the streets, cafes, and the Opera House in Cairo. The drama, announced in December 1893,141 is not analyzed here for its importance as a popularizing instrument (it was perhaps never performed), but for what it tells us about its young writer’s political imagination at the peak of dynastic patriotism and for what it indicates about the imminent demise of this peak.

The most important feature of this drama is the historical element. It adds medieval Muslim Andalusia, another chronotrope, to the repertoire of the learned Arabic historical imagination. By the 1890s, Andalusia was a symbol in Ottoman imagination, as testified by Ziya Pasha’s translation of Louis Viardot’s History of Andalusia, which was printed in Istanbul as early as 1859.142 But unlike its later use as a symbol of religious tolerance in the Arab, Ottoman, and Orientalist imagination, Kāmil’s play embodies the opposite: Andalusia stands for the conquest, the power of Islam, and its moral superiority over Christianity. As I read it, and as possibly Kāmil intended,143 the play embodies a youthful allegorical, moral vision of Abbas Hilmi II, an emir of a caliph, in the struggle against the British. Contrary to previous interpretations, I analyze this work as a peculiar instance of patriotism that appropriates Arab-Muslim history for Egyptian politics.144

The image of the nation in The Conquest of Andalusia is characterized by an interplay between the racial and religious categories. Kāmil composed the play in order “to show to my people (qawmī) the intrigues of the interlopers (dukhalāʾ) among the nations who wear their clothes and talk in their language” because “they are like poison in the body.”145 It seems, as also attested to by Muḥammad Farīd’s memoirs, that there was a growing awareness among Egyptians that the British-ruled government favored Syrians for high administrative positions. Kāmil’s concept of “interlopers” referred to these Syrians in Egypt. However, the words may reflect also the anti-Semitic discourse in France where the trial of Captain Dreyfus had just begun in November 1894 and where talk of “treason” was circulating everywhere, at the same time that Kāmil was finishing his exams. But the reader should not be misled. While the plot of the drama suggests an act of treason as the quality of race (the rūmī people, possibly Byzantines), and by extension the formulation of a morally superior “Arab nation” (al-umma al-ʿarabiyya), I argue in the following that its invisible problem is the political relationship between the ruler (an Arab prince) and his men.

The plot is set in 711 as the Muslim army prepares to launch an attack against the tyrant King Roderick (Ludhrīq) in Hispania. The dramatic conflict occurs between the emir Mūsā ibn Nuṣayr (the ruler of the Maghrib in the name of the Umayyad caliph), his vizier ʿAbbād of rūmī (perhaps Byzantine) origin, ʿAbbād’s rūmī love Maryam, and the rūmī friend Nasīm. Maryam and Nasīm ask ʿAbbād to find a means to stop the conquest and, thus, to betray Mūsā. After some consideration, ʿAbbād commits the treason, not only because he is of rūmī origin but also because he loves Maryam. He and Nasīm devise a plan in which they will send a letter reporting the death of the military leader Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād, compelling Emir Mūsā to call back the army. They plan then to kill the soldier who delivers their message. All unfolds as planned, until a letter arrives from Ṭāriq to the emir, reporting that he has conquered Andalusia and killed Roderick. The spy ʿĀrif confirms that ʿAbbād had sent a forged letter, thus making his treason known. In the final scenes, Mūsā and Ṭāriq meet in Andalusia at the head of the victorious armies, discuss the glory of Arabs and Muslims, and send ʿAbbād and his companions to prison.146

The drama is an allegory of an ideal Ottoman Egyptian (Muslim) Arab monarchy, that is, the khedivate. The play presents a prince who rules in the name of the caliph but is betrayed by his Christian grandee. The Muslim Arabs of lower ranks come to the ruler’s help. Apart from the French background of the Dreyfus Affair, it is hard not to find a similarity with the situation of Abbas Hilmi II in 1893. He was officially the caliph’s representative in Egypt, viewed as betrayed by the Syrian Christian editors of al-Muqaṭṭam and the old Nubar Pasha, but supported by the army and the students. Emir Mūsā symbolizes the khedive not only because of his position as an emir, but also because, by the end of play, he has come to function more like a national arbitrator. For instance, he turns to his “brothers, teachers of the nation, and scholars of the people” (ikhwānī asātidhat al-umma wa-ʿulamāʾ al-shaʿb) to compare the prudence of Ṭāriq and the treason of ʿAbbād.147 If we push the symbolic parallelism further, that is, if the character of Mūsā embodies Abbas Hilmi II, then Ṭāriq embodies Muṣṭafā Kāmil, preparing to conquer France for his prince. In the final scene, when both the ʿulamāʾ and the non-ʿulamāʾ of the people (qawm) are summoned to witness the sentencing of ʿAbbād, emir Mūsā delivers a speech in which he extolls the superiority of the Muslim nations (al-umam al-islāmiyya), summarises the moral of ʿAbbād’s treason (the power of love and women) and the dangers of the dukhalāʾ, and announces that Ṭāriq is “the exemplary hero of all times.”148 The emir does not forget to add that a state must be built on the firm basis of leading men. Fatḥ al-Andalus is thus a didactic work, or an expression of wishful thinking, in which the (Muslim) Arab nation is presented as capable of advancing only if powerful men remain loyal to the ruler. This was the lesson of patriotism in the imagination of Kāmil, a law student, in 1894.

Two contradictions run throughout the play. The first is the confusing message that ʿĀrif’s character sends, as spying is not morally positive. The author solves the contradiction by saying that, in this instance, spying is “an act of revenge” (intiqām) and “a service to Islam.” ʿĀrif notifies Ṭāriq about the treason in order to teach ʿAbbād a lesson, so he would “burn in hell.”149 Still, the constant spying is not truly justified by the plot. Second, this work is distinct from the earlier plays that set parallels between the khedivate and past empires in that it valorizes being an Arab and Muslim at the expense of others. The contradiction is between the moral use of the Arab past and Arabness, and the rejection of community with the dukhalāʾ “who speak the same language.”

While ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ al-Miṣrī’s 1871 play or even Maḥmūd Wāṣif’s 1886 comedy described Arabs as honest men without an “Other,” Muṣṭafā Kāmil’s drama contains a hierarchy similar to the French dominant discourse. For instance, ʿAbbād first considers an Arab to deliver his message. But he recognizes that “Arabs are famous among the nations (umam) for their strong attachment to the interests of their country and the devotion to their homelands (awṭān), because Arabs are very clever and smart people,” so he sends instead a Berber soldier who is easier to deceive and kill.150 The word and concept of “intruders/interlopers” would remain in the political vocabulary of Muṣṭafā Kāmil in his future speeches.151

The ideological landscape mirrored by The Conquest of Andalusia, a drama written by an enthusiastic twenty-year-old during the peak of learned patriotism, is an indication of the way national and revelation-based elements co-existed in this moment of symbolic uprising against the occupiers. The signs of a racial definition of the nation and the quest for a sovereign state are apparent. These elements indicate a new ideological direction. In the following years Muṣṭafā Kāmil would become the face of anti-British Egyptian nationalism, still an Ottoman, but no more a khedivial patriot.

CONCLUSION: THE END OF PATRIOTISM?

This chapter has surveyed the markers of distinction produced by economic and political transformation. The ideological product of this elite Arab Ottoman intellectual culture was a blend of patriotism, dynastic loyalty, Ottomanism, history, and Islam. I have analyzed this blend as Arab patriotism in the khedivate. We stop at this high moment of patriotism in the 1890s, without following the khedive and Muṣṭafā Kāmil’s eventual falling out, or the rise of anti-colonial nationalism lead by intellectuals such as Kāmil or Aḥmad Luṭfī al-Sayyid in 1900s Egypt. Various elements of Ottomanism remained strong until World War One.

We stop here in the 1890s because patriotism gave way to vernacular mass nationalism against the British, as well as to new ideologies, such as socialism, exemplified by revolutionary plays about social injustice. Muṣṭafā Kāmil died prematurely, and the khedivate’s last decade saw the crystallization of a new political force and vision, often independent of the khedive: territorial nationalism demanding the end of occupation, limitation of absolute power (new constitutionalism), and increasing reluctance to return to the Ottomans. In 1914, the British government abolished the khedivate and established a direct British Protectorate over Egypt. A new political pact had to be made.

1 Shārūbīm, al-Kāfī, Part 5, 1:1: 177–178.

2 The full evaluation of Abbas Hilmi II’s reign—the difficulty of which is best captured by the clash between the memoirs of Evelyn Baring (Lord Cromer) and Abbas’ own—is not the task of this chapter. However, it is worth noting that compared to the essays about Baring and Kāmil, no serious academic work has been written about Abbas Hilmi II, the third powerful actor of the era.

3 Al-Bakrī’s ideas and complex position should be the subject of a separate study.

4 Wāṣif, Riwāyat Hārūn al-Rashīd, 2.

5 Bourdieu, Distinction.

6 Bourdieu, “The Forms of Capital,” 48.

7 Egyptian and non-Egyptian historians often use the category of class to describe workers and middle class formation. Beinin and Lockman, Workers on the Nile; and Lockman, “Imagining the Working Class.”

8 Mestyan and Volait, “Affairisme dynastique.”

9 [Demolins], Dīmūlān, Sirr Taqaddum, 18–31.

10 ʿUmar, Kitāb Hāḍir al-Miṣriyyīn, 83. Cf. the interpretation of Roussillon, “Réforme sociale.”

11 ʿUmar, Kitāb Ḥāḍir al-Miṣriyyīn, 188.

12 Ryzova, The Age of the Efendiyya, 59.

13 Coury, The Making of an Egyptian Arab Nationalist, 64.

14 Selim, The Novel and the Rural, 5.

15 Gasper, The Power of Representation, 127.

16 Al-Farāyid, 15 May 1893, 174.

17 No historical work has been written about these crucial organizations, their function in society, or their economics from the late 1870s; only a short introduction can be given here.

18 Al-Ahrām, 17 May 1881, 2.

19 Republished in ʿAbduh, al-Aʿmāl al-Kāmila, 2:5–7. Originally al-Waqāʾiʿ al-Miṣriyya, 19 October 1880.

20 Sadgrove, Egyptian Theatre, 145.

21 Āṣāf, Dalīl Miṣr li-ʿĀmmay 1889–1890, 163.

22 Al-Hilbāwī, Mudhakkirāt, 118–119, Farīd, Mudhakkirāt, 186, etc.

23 Al-Ahrām, 26 February 1885, 2.

24 Al-Ahrām, 17 April 1885, 2.

25 Al-Ahrām, 12 April 1886, 3.

26 Al-Ahrām, 24 March 1887, 2.

27 Following Najm, Ismāʿīl, Taʾrīkh al-Masraḥ al-Miṣrī, 233–262 also lists a number of societies. Al-Dasūqī, Al-Taʾrīkh al-Thaqāfī, mostly repeats Ismāʿīl’s work concerning the theaters.

28 Najm, al-Masraḥiyya, 176–182.

29 Egyptian Gazette, 30 November 1882, 2.

30 Al-Ḥakīm, Dhikriyyāt, 21.

31 Wādī al-Nīl, 5 November 1869, 869. The advertisment says 120 or 1.20 “British pounds” as equvilant of 75 francs, but this seems to be a miscalculation.

32 Wādī al-Nīl, 3 December 1869, 972.

33 Draneht to Riaz, 21 February 1870, Maḥfaẓa 80, CAI, DWQ.

34 Lagrange, “Musiciens et poètes en Égypte,” 73.

35 Letter dated 18 March 1882, Paravey to MTP, Maḥfaẓa 2/1, Niẓārat al-Ashghāl, Majlis al-Wuẓarāʾ, DWQ.

36 Al-Hilbāwī, Mudhakkirāt, 73.

37 Ryzova, The Age of the Efendiyya, 115, 135.

38 Farīd, Mudhakkirāt, 102–103.

39 Ibid., 117.

40 Lagrange, “Musiciens et poètes en Égypte,” 152.

41 Badrawi, Ismaʿil Sidqi, 3.

42 Al-Hilbāwī, Mudhakkirāt, 118–119.

43 Egyptian Gazette, Supplement, 17 January 1895, 1.

44 Zaghlūl, Mudhakkirāt, 1:160.

45 Fahmy, Ordinary Egyptians, 89.

46 Muḥammad, Muqaddimat Kitāb al-Tuḥfa, 4.

47 Ibid., 6–7.

48 Ibid., 16.

49 Al-Ustādh, 7 March 1893, 673–686.

50 Farīd, Mudhakkirāt, 165.

51 Anṭūn, Miṣr al-Jadīda, pages bā–dāl.

52 Al-Ahrām, 31 October 1894, 4.

53 Ryzova, The Age of Efendiyya, 195 and 204.

54 This paragraph is based on various letters between 1869 and 1878 in Maḥfaẓa 80, CAI, DWQ. For the ruler as a patriarch within the dynasty, cf. Konrad, Der Hof der Khediven, 168–170.

55 Jerichau-Baumann, “Egypt, 1870,” 281.

56 Shafīq, Mudhakkirātī, 1: 57–58. This supposes that the tickets were not checked or marked at the entrance.

57 Harrison, The Homely Diary, 50–52.

58 Fikrī, Irshād al-Alibbā, 2: 713–714. Reid, Whose Pharaohs?, 250 states that Aida was also performed, but I do not find any trace of this. See also La Turquie, 28 September 1889, 2 in which the (possibly French) journalist mocks the Egyptian delegation.

59 Kāmil, Miṣr wa-l-Iḥtilāl al-Inklīzī, 130–151 (with the ensuing debate about the dukhalāʾ).

60 Al-Ahrām, 16 March 1885, 2.

61 Egyptian Gazette, 14 January 1895, 3.

62 Letter dated 19 September 1897, from ʿAbd al-Karīm Mūsā to Minister, 4003–036055, DWQ.

63 Al-Qāhira (al-Ḥurra), 22 May 1888, 3.

64 La Correspondance Égyptienne illustrée, 1–8 April 1896, 4–5.

65 al-Muwayliḥī, A Period of Time, 299.

66 Zádori, Éjszakafrikai útivázlatok, 95.

67 Al-Khulaʿī, Al-Mūsīqā al-Sharqī, 172, n. 1.

68 Al-Ahrām, 29 June 1886, 2–3.

69 Al-Qāhira (al-Ḥurra), 5 January 1887, 2.

70 Cf. various letters in AHP.

71 Hornik, “The Mission of Sir Henry Drummond-Wolff.”

72 Peri, “Ottoman Symbolism”; Hirszowicz, “The Sultan and the Khedive”; Deringil, “Ghazi Ahmed Mukhtar Pasha”; Owen, Lord Cromer, 217.

73 Al-Ahrām, 30 April 1884, 3.