In a small tribe of low degree we call him the headman; in more advanced or larger communities we call him the king. Sometimes we hesitate between chief and king. Our use of these terms is rather arbitrary: we translate the native word one way or the other, according as the state kept by the principal comes near to our idea of a king, or falls short of it, and our kings keep very great state. Such a distinction is one of externals, of pomp and circumstance, whereas we are trying to get at the inner meaning. If a distinction is to be made it must be based on the whole structure, because the structure reflects meaning; not on an accident such as the extent of square miles ruled, or the size of the civil list.

—A. M. Hocart,

Kings and Councillors

FEW ISSUES HAVE captured the attention of social theorists more than the genesis and generation of social inequality in putatively egalitarian contexts. Most scholars agree that asymmetries of social power and status grace even the most egalitarian of documented human societies; nonhuman societies are likewise characterized by hierarchical relationships, although for the most part they are not based on hereditary ascription of rank. But the social trajectories of human groups are frequently marked by a willingness to trade the autonomy of the sovereign individual for the autocracy of the individual sovereign, and in many respects the reasons why remain as elusive today as in centuries past.

Chiefdoms represent a bastardized concept, a diminutive form of kingdoms lacking kings, complex polities lacking the standing armies and sitting bureaucracies of states. Originally defined as part of an evolutionary stage sequence, chiefdoms served to partition organizational variability between politically decentralized tribes on the one hand and states on the other, while the most commonly used definition was crafted to provide a necessary logic for their existence. In recent years many scholars have challenged particulars of this construct (especially the coordination of locally specialized production, which was its original raison d’être), and some now argue the concept has limited practical utility. Most scholars, however, would still recognize a broad class of middle-range societies—ethnographic and archaeological—characterized by systematic, permanent, pervasive, and heritable forms of social inequality but lacking key organizational features of state-level polities, and at least some would call these polities “chiefdoms.” These scholars differ, sometimes in bitter ways, over whether this range of social forms should be viewed as an empirically extant modal form or simply a useful analytical construct, over the key features and dynamics of chiefdoms, over the role of agency and action in their formation, operation, and decline, and over the validity and utility of evolutionary approaches to chiefdoms. In this chapter, my goal is to situate theoretical debates over the concept and character of chiefdoms within a broader set of issues regarding agency, action, and the constitution of society in general. Many important contributions and the work of major scholars in this area are not given the space they deserve (or any space at all) because of the necessary brevity of this chapter.

The concept of chiefdom, as commonly used, grew out of a neoevolutionary paradigm that has been criticized, on the one hand, for being directional (Dunnell 1980; Wenke 1981; Rindos 1985) and on the other for ignoring the contingent historicity of social change (Hodder 1982, 1986; Kirch and Green 1987; Friedman 1975). Scholars differ over the nature of that evolutionary change. Many see it as a gradual, quantitative process leading to increasing stress, eventually resulting in either collapse or qualitative transformation (Wright 1977; Cordy 1981), or as an abrupt flashpoint (Carneiro 1998:25; Flannery and Marcus 1999). Others argue that the sequence would have been transparent to those who lived it (Johnson and Earle 1987). As a rule, most critiques of chiefdoms as an evolutionary taxon have focused on empirical exceptions to proposed general characteristics (Finney 1966), specific aspects of evolutionary schema (Blanton et al. 1981), inferred progressivism (Dunnell 1980), or the punctuated equilibriums such frameworks seem to imply (Plog 1977; Harris 1979; Renfrew and Cooke 1979; Kehoe 1981; Wenke 1981; McGuire 1983; Creamer and Haas 1985; Sanderson 1990).

Despite these critiques, the chiefdom concept enjoys considerable currency. While there is little consensus regarding the nature of chiefdoms sui generis, typologies of different kinds of chiefdoms abound.1 Among these are Renfrew’s distinction between individualizing and group-oriented chiefdoms (1974), Taylor’s (1975) division of African societies into nonranked chieftaincies, ranked chieftaincies, and paramountcies, Goldman’s division of Polynesian societies into traditional, open, and stratified (1970), Steponaitis’s distinction between simple and complex chiefdoms (1978), Johnson’s separation of sequential and simultaneous hierarchies (1982), Keegan and Maclachlan’s identification of avunculocal chiefdoms (1989), and Blanton’s distinction between chiefdoms characterized by corporate or network strategies (Blanton et al. 1996).2 Theorist Robert Carneiro has proposed at least three different typologies of chiefdoms (Carneiro 1998:37 n. 1).

Like most bastards, the concept of chiefdom has an uncertain genealogy. Renfrew (1984:228) derives the concept from Paul Kirchoff’s notion of the conical clan on the one hand and Raymond Firth’s description of ramages on the other. Carneiro (1981:38) traces the concept to Julian Steward’s (1946:4; 1948:1–4) distinction between lowland tribes and circum-Caribbean cultures, recapitulating Cooper’s (1941, 1942) fourfold culture division of South American groups into marginal hunting and gathering tribes, Andean civilizations, tropical forest and savanna tribes, and circum-Caribbean cultures. That the circum-Caribbean culture type was to be viewed as a particular scale of social integration is made explicitly clear (Steward 1948:8). But the term “chiefdom” does not actually appear in any of these studies.

Both inchoate concept and term can be found at an earlier date in the Africanist literature. It appears, for example, in African Political Systems (Fortes and Evans-Pritchard 1940; cf. Richards 1940:92). While the term “chiefdom,” referring to the same kinds of societies, was used informally in these earlier studies, it was given formal meaning by Kalervo Oberg (1955), who had contributed to Fortes and Evans-Pritchard’s volume (Oberg 1940:121–162). Oberg considered not only the status of the chief but also the territorial and political organization of the chief’s domain. An integrative, collectivist approach is explicit, as social taxa are described as “functionally interrelated constellations of cultural forms” (1955:472). His taxa include homogeneous tribes, segmented tribes, politically organized chiefdoms, feudal-type states, city states, and theocratic empires (1955:472–487). Chiefdoms, for Oberg, represent multivillage territorial polities governed by a paramount. Chiefs have judicial powers to settle disputes and requisition men and materiel for war (1955:484). The term was similarly used by Eisenstadt (1959) in his classification of African political systems and by Steward and Faron (1959) in their ethnological treatment of South America. Other scholars (Mitchell 1956; Southall 1956; Sahlins 1962) adapted it to discuss political dynamics in middle-range hierarchical societies. In many of these studies chiefdoms figured in taxonomic arrangements, typologies of hierarchical societies subject to a Hocartian critique (see chapter epigraph).

Eisenstadt (1959), for example, proposed a classification of African political systems that included centralized monarchies (e.g., the Ngoni, Swazi, Tswana, and Zulu) and federative monarchies (Bemba, Pondo, Ashanti, and Khoisa). The key difference between centralized and federative monarchies lay in how allegiance to the chief was situated. In centralized monarchies, allegiance was directly to the chief and did not require membership in subsidiary groups or factions. As a result, these systems were characterized by universal membership in the widest political unit of the society. In contrast, Eisenstadt’s federative monarchies were based on the allegiance of subchiefs or other kinship or territorially based authorities, to whom people of lesser rank owe allegiance. Due to organizational limitations on delegating authority, paramounts may have greater control over local chiefs than they do over that chief’s followers (Barker 1999; Wright 1984). Although he lived in a feudal system, John de Blanot’s thirteenth-century maxim “my man’s man is not my man” (Acher 1906:160) encapsulates the same source of instability and factionalism in chiefly systems.

The distinction between centralized and federative monarchies parallels Southall’s (1956:248–251; 1965:126–129) separation of hierarchical from pyramidal political systems, whose related discussion of associational versus complementary delegation of power foreshadows later arguments by Wright (1977; 1984:42–43). Eisenstadt (1959:216) concludes that the various political forms reflect “the main goal and value-orientations of a society” (Lewis 1959). It should be noted, however, that Taylor (1975:195–197) found only one case in her sample of African societies where surplus was acquired through direct (centralized) taxation, instead of indirectly through alliances with local chiefs (i.e., federative relations; see also Schapera 1956), and that was Buganda, a state-level polity.

Steward and Faron (1959) similarly emphasize the variability manifest in chiefdoms. “No societies of South America,” in their view, “were so kaleidoscopically varied as the chiefdoms” (1959:175). While acknowledging a broad range of variability, they distinguish two general kinds of chiefdoms: (1) militaristic chiefdoms integrated by warfare and (2) theocratic chiefdoms integrated by religious and ideological elements. Within these groups, Steward and Faron recognized considerable variability, largely reflecting particular circumstances and historical contingencies (1959:176–177):

The present broad category of chiefdoms serves to distinguish a culture type characterized by small, class-structured states from the lineages and bands of nomadic hunters and gatherers, the independent villages of the tropical-forest riverine and coastal people, and the irrigation states and empires of the central Andes. The local differences between the chiefdoms represent an interaction of two factors. First, food production in the extremely varied environments afforded differing amounts of surplus and consequently permitted specialization, class formation, and state development in different degrees. Second, not only were different cultural features borrowed from different areas, but they were locally patterned in different ways.

Although this may resemble the progression (bands, tribes, chiefdoms, and states) that Service (1962) would soon define, Steward and Faron (1959:178) specifically argued that chiefdoms should not be viewed as evolutionary stages. In fact, Steward and Faron regarded chiefdoms as representing a range of social forms, incorporating considerable diversity in structure, operation, and developmental trajectory.

Service’s Primitive Social Organization (1962) redefined the chiefdom, making it an organization different not only in scale but in kind. Chiefdoms, for Service, are more dense, complex, and economically productive than tribes (1962:143), and are characterized by both pervasive social inequality and permanent structures of economic and political integration. No longer a segmentary social order, the chiefdom for Service was predicated on specialization of both production and function. Specialization of production was thought to take one of two forms: (1) regional specialization of production by different local residential units (assumed by Service to be the more common) and (2) pooling of individual skills in large-scale cooperative endeavors (Service 1962:135). In simpler societies, people relocated themselves to resources. In chiefdoms, resources were generally moved to people. Chiefs were thought to reallocate the surpluses of local units, so that each unit focused on specialized products suited to its local circumstances, yet still met its general needs through the productive efforts of other units redistributed by the chief. Service’s classification combined the primarily political properties used by previous studies with a progression of economic forms (Polanyi 1957, 1944; Meek 1976) that both defined each stage and drove change from one to the next.

. . . a chiefdom differs radically from a tribe or band not only in economic and political organization but in the matter of social rank—bands and tribes are egalitarian, chiefdoms are profoundly inegalitarian. But however salient the personal, individual ranking as a social feature of developed chiefdoms, it should be re-emphasized that this is a consequence of the development of a coordinating center, not its cause. (Service 1962:150)

Redistribution is not a characteristic of chiefdoms, but quite literally their sine qua non.3

Service’s division of organizations into segmentary and organic (following Durkheim) was pivotal to his discussion of chiefdoms. For Service, the crucial transformation in the human career lay in the rise of chiefdoms—societies organic in constitution and characterized by extralocal structures of authority and production. By making specialization definitional, Service required a form of organic solidarity within chiefdoms, with redistribution being the glue that held them together. Local units were not self-sufficient; sufficiency was the product and promise of the whole. From a practical standpoint, Service redefined redistribution as the allocation of specialized produce between economically differentiated units in an organic system. This allowed Service to maintain the complementarity of social institutions, reconciling an implicit hylomorphic distinction between material (economic) and formal (political) organization, while at the same time defining a level of social integration based on their intersection.4 Two decades later, Giddens (1984:258) made a similar distinction between allocative (economic) resources and authoritative (political) resources. Feinman and Neitzel (1984:40) interpret Service as dividing societies intermediate between bands and states into tribes or chiefdoms based on whether they exhibit reciprocal or redistributive economies. This is only partly correct; chiefdoms are redistributive societies, but they are also characterized by a centralized redistributive office. Absent that centralized redistributive office, Service explicitly would not consider that society a chiefdom (1962:150).

In many cases, however, redistribution may have played no direct role in the spread of chiefdoms. Organizational efficiency, including the ability to allocate larger surpluses, field larger armies, and maintain coherent military command and control, may have given chiefdoms a significant edge over nonhierarchical neighbors. “Once a chiefdom (even slightly developed), is pitted against mere tribes it will prevail,” Service writes (1962:151). Robert Carneiro and his colleagues, whose earlier studies had influenced Service in his chiefdom construct (Service 1962:147), developed this viewpoint (Carneiro 1990, 1991; Redmond 1994, 1998). Carneiro (1988, 1978, 1970, 1967) sees social and population pressure increasing in areas of circumscription or resource concentration.5 Competition leads to warfare, and warfare breeds chiefdoms (Carneiro 1981:66). Carneiro (1981:45) defines chiefdoms as multicommunity polities under the control of a chief, and from this perspective the crucial problem is less the rise of social inequality than how village autonomy could have been surmounted. Autonomy, in this view, is never surrendered willingly but only through direct force on the one hand or coercion and intimidation on the other (Carneiro 1998:21). Chiefdoms, then, develop when a powerful war leader conquers the polities around him (1992:198). More recently, Carneiro (1998) has focused on the ability of the war leader to maintain this control into times of amity.

While few theorists would deny that warfare seems to be a general characteristic of chiefdoms (Earle 1987:293), and studies of the iconography of chiefdoms often emphasize warfare and military exploits (Linares 1977; Kelekna 1998), there is little consensus regarding the primary, causal role warfare is sometimes accorded in the rise of chiefdoms. “One can hardly escape the conclusion,” Carneiro writes, “that it was the ability of a successful war leader to continue to maintain control over subordinate villages, instead of relinquishing it during peacetime, that constituted the most likely avenue for the emergence of the chiefdom” (1998:28). Other approaches, however, emphasize other avenues.

In an influential study establishing archaeological correlates for chiefdoms, Peebles and Kus explicitly distanced the concept of chiefdom from redistribution (1977:423–427), while retaining a collectivist viewpoint focusing on the broader efficiencies of hierarchical organization. Based in part on their reanalysis of Hawaiian ethnographic data, and in part on the work of Timothy Earle (1973), they argued that (1) redistribution was not the dominant mode of exchange; (2) goods which were redistributed were generally provided to elites, not commoners; and (3) redistribution did not serve to unite ecologically or economically diverse zones or villages (1977:424). Instead, they approached the rise of chiefdoms in cybernetic terms, where rank societies emerge as homeostatic equilibriums maintained by negative feedback between elements of the system (Flannery 1972; Wright and Johnson 1975).

If a cultural system is operating at or near its capacity to process information, and the inputs of critical information from one area of the environment increase beyond the system’s capacity to process these inputs, then either: 1) inputs from other areas of the environment will have to be (a) filtered or ignored or (b) buffered for action at a later date; 2) channel capacity will have to be increased either (a) through change in organization or (b) through change in the mechanism of information processing; or 3) system overload will take place and homeostasis will cease. (Peebles and Kus 1977:429)

Chiefdoms provide a more efficient means of processing information, a hierarchical decision-making system in which specialization of function increases the overall capacity of the system to respond to changing variable states or needs. Such systems, they argue, offer an increase in the quantity and complexity of information that can be processed, an increase in the maximum number of individuals that can be integrated into a cultural system, an increase in other kinds of economic specialization, improved buffering against environmental fluctuation, and greater speed of response. Like Service, Peebles and Kus see chiefdoms as representing a fundamental shift from Durkheimian mechanical to organic forms, but see this specialization in terms of regulatory and cybernetic efficiency.

Peebles and Kus (1977) predicted that archaeological evidence would reflect the cybernetic characteristics of hierarchies in that (1) group-scale and individual-scale status dimensions should be separable; (2) settlement hierarchies should be visible, reflecting each settlement’s position in the administrative hierarchy; (3) relatively limited economic or ecological variability should exist within hierarchical levels, in order to maximize sufficiency and reduce information overhead; (4) evidence should indicate mobilization of surplus labor for public works or craft specialization; and (5) forms of environmental (ecological and social) variability potentially affecting homeostasis should be buffered or monitored.

Although these are many of the benefits Service (1975) had identified as accruing from increasing sociopolitical complexity, Peebles and Kus (1977) explicitly rejected Service’s restricted form of redistribution between disparate economically or ecologically specialized communities because of the regulatory costs it implies. Instead, they argued for a more general redistribution, which serves as a buffering mechanism for maintaining systemwide homeostasis.

Processualist approaches continue to emphasize the functional or adaptive advantages of increasing complexity. Halstead and O’Shea (1982), for instance, argue that complexity serves important functions in buffering against shortage in lean times, not only through the ability of chiefs to provide resources in times of need, but also by mobilizing resources—of materials, information, or energy—on a scale unavailable to households or egalitarian structures.

The most powerful mechanisms . . . are those that cope with problems of unusual severity or exceptional scale. Although prone to falling into disuse because of the infrequency with which they are activated, these high-level coping mechanisms [assistance by the elite] may serve a critical function in cases of extreme shortage. As a result there is a strong selective pressure for them to become increasingly embedded within more regular cultural practices and so, potentially, to develop widespread ramifications throughout the social system. (Halstead and O’Shea 1989:5–6)

Such collectivist viewpoints can be contrasted to a range of individualist, materialist approaches. Morton Fried played Marx to Service’s Hegel with The Evolution of Political Society (1967). Fried describes a rank society (1967:169) bridging the divide between acephalous and state-level societies.6 Fried does not see local specialization as central to these ranked societies, nor does he interpret them in collectivist terms. Instead, he adopts an individualist approach (via Marx) that sees rank in terms of differing levels of access to the means of production. The distinction between tribes and chiefdoms is clearly if tacitly rejected, as Fried argues that “tribes” as commonly conceived are less pristine organizational patterns than the results of contact and social fragmentation (1967:170; Fried 1975).

The rise of individuals with differential access to or control over resources is not, for Fried, a social question. It is a political question and reflects political processes manipulated by individuals:

Legitimacy, no matter how its definition is phrased, is the means by which ideology is blended with power. Legitimacy is most clearly grasped in terms of its principal functions: to explain and justify the existence of concentrated social power wielded by a portion of the community and to offer similar support to specific social orders, that is, specific ways of apportioning and directing the flow of social power. (1967:26)

Fried does, however, recognize the importance of redistribution. In reviewing ethnographic cases, he sees ranked societies being premised on only two factors: (1) ecological demography and (2) the emergence of redistribution (1967:183). To relegate Fried to the status of an adaptationist for his reliance on redistribution (Brumfiel and Earle 1987:2) misses his clear insistence on the political premise of power. However, despite his Marxist-inspired arguments that attribute political processes to individuals or interest groups, Fried’s model did not really provide meaningful engines for social change. Fried’s (1967:183) insistence that the rise of political complexity was gradual, unremarked, and unnoticed by participants conflicts with more commonly articulated Marxist approaches, which presuppose that perceived asymmetries in key relations are a necessary concomitant to social process and change.

More recent Marxist analyses (McGuire 1992; Gilman 1995) focus less on universal stages than on finer-grained analyses of the effects of general pathways to inequality in particular historical circumstances. Gilman (1995:242), for example, argues that increasing complexity in northern Europe can be understood in terms of the internal dynamics of a Marxian “Germanic social formation” in which power accrues to “the wealthy purveyors of effective violence” able to extract tribute from agricultural producers. Another influential, change-oriented individualist approach can be traced to the work of Catherine Coquery-Vidrovich (1969:61–78) and her analysis of the African mode of production (Coquery-Vidrovich 1977; Peebles 1987:34; see McGuire, chapter 6).

Along these lines, scholars such as Jonathan Friedman, Susan Frankenstein, and Michael Rowlands adopted the notion of the prestige goods economy, taking the term, albeit not necessarily the concept, from the earlier work of Herskovits (1940) and Bascom (1948). In the original model, a prestige goods economy involved any “goods through which social approval and social status are gained” (Bascom 1948:211). Bascom (1948:220–221) identified certain subsistence foods (yams and pit breadfruit) that served as prestige items, which meant that these subsistence goods were overproduced and thereby buffered the prestige system against shortfall. In contrast, the prestige goods chiefdom was a system where power was gained and maintained by control of exchange items originating in far-off or otherwise remote places, and whose value was based not on everyday utility but on socially restricted gift-debt exchanges usually associated with asymmetric marriage patterns (Friedman 1975; Friedman and Rowlands 1977:208–211; Frankenstein and Rowlands 1978). This differs from the original model of the prestige goods economy in its structural-Marxist view of asymmetrical affinal relations creating and reproducing inequalities, resulting in differentiation of wealth between kin groups. Rather than coordinating production, chiefs control relations of production in order to leverage differences in status created through social reproduction.

Frankenstein and Rowlands (1978:76–77) sum up the main elements of their argument with admirable clarity:

The specific economic characteristics of a prestige goods system are dominated by the political advantage gained through exercising control over access to resources that can only be obtained through external trade. However, these are not resources required for general material well-being or for the manufacture of tools and other utilitarian items. Instead, emphasis is placed on controlling the acquisition of wealth objects needed in social transactions, and the payment of social debts. . . . At this point in the process of hierarchisation a dominant chief can reinforce social control over the internal circulation of wealth objects by narrowing down and monopolising the range of items acceptable in social transactions within his domain. The use of domestic wealth objects will be devalued and restricted to relatively minor social transactions, and a sphere of foreign wealth objects will be formalised to take their place. . . . The chief’s control over external trade in wealth objects is absolute so that he alone obtains commodities from a foreign source which he can then redistribute in the form of status insignia, funerary goods, bridewealth, etc.

Central to prestige goods constructs are a set of simple internal asymmetries driving change. Rather than seeing institutions in collectivist terms and explaining how they work together, such models describe an unbalanced system and explain how it continually pulls itself apart. Friedman and Rowlands trace how institutions themselves are transformed through these processes.

Change in cultural form as well as place in material production occur simultaneously in the process of reproduction so that evolutionary “stages” are always generated from previous stages in such a way that we might speak of epigenesis; structural transformations over time in which the nature of the trajectories is determined by the properties of an arbitrarily chosen initial state in given conditions of reproduction. (1977:204)

The redistributive system loses its former function as a means of converting surplus into status in an act of “generosity.” Since status is “given,” such generosity is now reduced to an expression of segmentary position. The conical clan chief or king is entitled to tribute and corveé on the basis of his necessary function in the ritual-economic process, not because he might return all this accumulated wealth in the form of feasts. Increasing surplus is no longer redistributed in the same manner as previously. (1977:217)

Welch (1991:18) notes that the construct is neither based on nor presented as an ethnographic case study. Its structural-Marxist approach is based, however, on a variety of secondary ethnographic sources, including Ekholm (1972), Sahlins (1963, 1968, 1972), and Strathern (1971). In their key features—the generation of political and social asymmetries through the iteration of a Lévi-Straussian form of generalized reciprocity, coupled with a heterodox Marxist construction of the local population model (Friedman and Rowlands 1977:203, fig. 1)—these approaches are individualist in character, based on opposition between “self” and an externality which drives change. Frankenstein and Rowlands (1978), who grounded their discussions in a series of ethnological studies, stressed that the key factor in the emergence of hierarchically ranked, middle-range societies was the presence elsewhere of preexisting, more complex polities from whom prestige goods could be drawn, and with whom relationships could be controlled.

Competition between centres at the local level (periphery) is likely to be replicated and stimulated by competition for dominance amongst their external trading partners (core centres). . . . Since the expansion of core centres is dependent on their capacity to monopolise their peripheries, this must entail the reciprocal development of competing points of accumulation within the core area consistent with their ability to control access to resources in the peripheral areas. Hence, the emergence of local competing centres in peripheral areas is directly related to the emergence of competing centres in the core area. (Frankenstein and Rowlands 1978:80)

In such a system, political power is not linked directly to subsistence, “so that by definition foodstuffs would not be passed up as tribute” (1978:81). This has important consequences. The increasing ratio of consumers to producers (as the number of artisans creating prestige goods increases) must be supported by the chiefly clan or immediate kin group, since foodstuffs are used only to support segmental and local authorities (1978:82). In Southall’s (1956:248–251, 1965) terms, the construct presupposes a pyramidal rather than hierarchical organization, where the paramount receives direct support only from his home domain(s).

Prestige goods exchange has largely supplanted redistribution as both economic basis and necessary cause for many scholars studying chiefdoms (Friedman and Rowlands 1977; Frankenstein and Rowlands 1978; Kipp and Schortman 1989; Wells 1980, 1984; Haselgrove 1987; Dyson 1985). While Schneider (1977:23, 27) cautioned that exchange of sumptuary goods was “no less important” than exchange in subsistence items (e.g., Tourtellot and Sabloff’s [1972] distinction between “useful” and “functional” items), more recent studies even challenge whether subsistence items played any role at all (Kipp and Schortman 1989).7 Welch (1986) examined archaeological evidence for the economic basis of the Mississippian center at Moundville, in the American Southeast, and found that a prestige goods economy (sensu Frankenstein and Rowlands 1978) provided the best fit (1986:192); Junker (1990, 1994) found that Philippine chiefdoms used exotic prestige goods both to affirm their legitimacy and to create political alliances (Helms 1988, regarding the use of long-distance trade and geographical distance in the legitimization of chiefs).

These same critiques of Service’s definition gave rise to mobilization constructs, individualist approaches to regulatory strategies focusing on the maintenance of power by the chief, rather than maintenance of assorted systemic equilibriums by society as a whole. A series of studies showed that while substantial amounts of comestibles and crafts flowed up the hierarchy to the chief, a much smaller volume of goods flowed back down (Earle 1973, 1977, 1978; Taylor 1975; Helms 1979; Steponaitis 1978; Wright 1984). As Wright (1984) moved toward an individualist, mobilization viewpoint, he attributed the role of regulatory mechanisms less to ensure systemic stability (Wright 1977) and more to make sure that followers control sufficient stores of socially necessary goods to maintain status without accumulating enough to mount a successful challenge. Although Welch (1986:15) criticized Wright’s (1984) model as “explicitly a re-expression of Peebles, and Kus’s . . . interpretation of Hawaiian economic structure,” Wright’s model clarifies the role of the regulatory mechanism as one whereby reciprocal relations can be made into tributary relations. Perhaps more importantly, Wright (1984) suggested mechanisms by which collectivist logics might be coopted by individuals over time.

Following this, increasing social complexity can be viewed as “dependent on the mobilization and use of surpluses to finance the emerging elites and their associated institutions” (Earle 1987:294). Unlike the prestige goods approach, mobilization constructs assumed that staples formed a central element of chiefly finance. Staple finance (D’Altroy and Earle 1985) provided resources to elites as a form of rent, generally for land made available by them for use by producers, although elite control of other key resources could result in similar effects. These resources were used to support not only nobles and their retinues but also craft specialists attached to elite households. In some cases elite households may have controlled the production of tools or other economically necessary items, although this is held to be uncommon (Earle 1987:295–296). More common, according to the mobilization approach, is the production of wealth objects by attached craftsmen. Prestige goods economies can be seen as a subset of wealth-finance systems. Because of the theoretical assumptions of the mobilization approach, however, wealth finance is viewed as a less stable strategy offering “only limited opportunities in chiefdoms” (Earle 1987:297). Earle (1997) has prepared a detailed comparison of environmentally and historically diverse examples of the rise of chiefdoms; his multilinear evolutionary approach to chiefdoms from a mobilization perspective has been influential and widely adopted (Earle 1989, 1987).

Closely related to this approach has been an emphasis on the role of factional competition in the emergence of elites (Brumfiel and Fox 1994). Clark and Blake (1994:18–21) provide a construct in which aggrandizers compete for prestige and social esteem, creating a complex and dynamic web of relationships as social creditors and debtors. Because these patron-client relationships can take place at a variety of overlapping scales, and because the same person might be client or patron at different times or in different settings, the construct offers more latitude for social action than top-down theories do (Brumfiel 1994; Pohl and Pohl 1994; Hayden and Gargett 1990; Spencer 1994). Aggrandizers succeed through generosity, by creating and manipulating social debts that may eventually be institutionalized as differential status. While the construct focuses on competition for prestige, greater access to physical resources is an epiphenomenal but real effect (Clark and Blake 1994:18); the ability to pass on both social and economic advantages to one’s heirs marks the transition to chiefdoms.8

More recently, elements of the prestige goods and mobilization constructs have been combined.9 Blanton et al. (1996) propose two alternative strategies for political and economic differentiation. Network strategies involve leveraging long-distance exchange relationships and manipulating the resulting esoteric knowledge and prestige in advantageous ways. In theory anyone could attempt to parlay networks into prestige; in practice emerging elites solidify their position by making these arrangements exclusionary, either through formal prestige goods economies or amplification of household, descent, or similar ties through patrimonial rhetoric (Blanton et al. 1996:5), thereby reducing the field of competing individuals to high-ranking members of those patrimonial groups. Corporate strategies, by contrast, emphasize group solidarity through collective action, monumental architecture, and fixed interdependence between subgroups on the one hand and between elite and commoners on the other (Blanton et al. 1996:6). Both strategies are used by Mesoamerican elites, and Blanton et al. (1996:12) suggest that the complexity of archaeological sequences in the region reflect, in part, the interplay of the two.

Another theoretical perspective has focused on the ideological premises of elite emergence. Pauketat (1991) articulates a complex individualist, agency-based position, combining a rich set of theoretical approaches with the rise of Hobbes’s Leviathan as leitmotiv for the rise of the major Mississippian mound center of Cahokia.

As currently conceptualized, the chiefly personages of both simple and complex hierarchies engage in political strategies in order to perpetuate their authoritative positions and preserve the social order as a whole. While such reproduction similarly constrains the form of social and economic relations, the latter are unnecessary defining attributes for chiefdoms. Thus attention actually has been focused away from a societal type—chiefdom—and onto political process. (Pauketat 1991:11)

Pauketat argues that the process of political centralization creates core-periphery relations. Because the scale and structure of these relations varies with period, the only meaningful parts of the world system approach “are the definitional characteristics of hegemony” (Pauketat 1991:12).10 Two such characteristics are felt to apply: (1) core groups dominate peripheries within the region because they have more political/alliance options available to them and (2) core groups marginalize peripheral groups by extracting resources from the periphery in order to reproduce the political hegemony (Pauketat 1991:13; Ekholm and Friedman 1985:110; Kohl 1987:16). Somewhat tautologically, the periphery cannot achieve political-economic parity with the core because the peripheral groups are alienated from their own social reproduction, which itself is articulated with the core (1991:13; citing Gledhil and Rowlands 1982:146–147). The reproduction of hegemonic relations also required the demonstration of knowledge of and control over geographically or temporally distant phenomena through the prestige goods economy in order to maintain the ideological basis of power. Pauketat (1991:14) argues, however, that core-periphery constructs are “sterile in the absence of a political-ideological element”:

Political economy and ideology are to be articulated within a dialectical understanding of the internal-structural (i.e., cultural) logic and the external conditions (i.e., historical/core-periphery context). The distinction between infrastructure and superstructure falls away in this anthropological critique of political economy. . . . Emphasis is placed on the conflicting interpretations and the negotiation of cultural meanings as these affect and are affected by social actions. (1991:14–15)

The aristocratic class would see itself as “a genealogically separate group, more closely related to each other than to the members of the local commoner populations” (Earle 1978:12–13). In general agreement with this view, Pauketat (1991:10–11, 44) also grants that commoners need not be “completely cutoff genealogically from the elite group,” as at least the appropriation of goods by the elite is offset in a “token manner” (1991:44) by giving feasts, enacting ritual events, and sharing stored food in times of shortage. More recent work by Pauketat expands the latitude for meaningful action (albeit not necessarily agency) by commoners, noting that the interrelated practices of elites and commoners led to the rise of both Mississippian mounds and the social hierarchies they supported, both literally and figuratively. It is not clear, however, whether this was the end intended by all involved (Pauketat 2000).

A series of important studies have focused on modeling how chiefdoms operate; whether these are models of the political or economic operation of chiefdoms depends on one’s theoretical orientation. While recognizing the heuristic value of separating the two, I remain unconvinced that the separation is meaningful in such settings.

In a seminal essay, Vincas Steponaitis (1981:323) argued that the degree of centralization of a chiefdom can be measured by assessing the relative amount of tribute controlled by a given administrative level and that controlled by the next lower level. He developed formal models for the movement of comestible resources within a multitiered administrative hierarchy. His model is based on Elizabeth Brumfiel’s (1976) test of the population pressure hypothesis in the eastern Valley of Mexico. Brumfiel (1976:237) argued that if population pressure were a significant factor, then there should be a correlation between the relative number of inhabitants of each village and the relative productive potential of agricultural land available to that village. She calculated the approximate catchment productivity and arable catchment (5-kilometer radius) for a series of Formative sites, generating a proxy value for potential productivity, then conducted a linear regression analysis comparing these values to site size. She found (1976:247) that there was no single relationship, but that separate relationships obtained simultaneously for sites of different sizes, and suggested this reflected the effects of tribute mobilization.

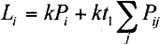

Steponaitis (1981) recognized that these relationships could be used to calculate the actual amounts of produce flowing up the hierarchy. He proposed that in autonomous villages, the site size Vj would be a function of the productivity of the catchment Pj, such that Vj = kPj, where k is a constant representing the number of people supported per unit of productivity. In a two-level hierarchy, village production is a function of catchment productivity minus the fraction t of that productivity paid as tribute, such that:

Vij = K(Pij–t1Pij) or Vij = k(1–t1)Pij

Where Vij is the jth village of the ith district, Pij is the catchment productivity, and t is the percentage rate of tribute. Centers enjoy not only the resources of their own catchment, but also the produce of surrounding subsidiary sites from whom they receive tribute. Centers further include two resident groups, producers (Sp) and nonproducers (Sn). The population of the center is simply the sum of these groups (L). The population of producers is essentially the same term as that used in villages (k(1–t1)Pi), plus a new term for the summed tribute received. This can be simplified to:

In such a system, if the rate of tribute remains constant for all villages, then the centers will fall along a line of slope k. The y-intercept for k will always be greater than zero because of the additional provisioning mobilized from subsidiary sites. Even if a center had no productive catchment, it could still maintain a population as a function of the aggregate tribute collected.

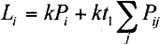

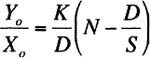

Steponaitis’s (1981) final set of equations for the population of the paramount centers, designated R, includes terms for the production, Pr, of the producers in the paramount village, the tribute t1 forwarded by other villages in the paramount’s district, and the tribute t2 forwarded to the paramount by secondary centers. The equation is (Steponaitis 1981:329):

where R is the paramount center population, Pr is the productivity of the paramount center’s catchment, and Prj. is the productivity of the jth village in the paramount’s district.

For Steponaitis this allows the amount of tribute controlled at each level of the hierarchy to be calculated:

Stating the matter more precisely, it can be shown mathematically that the vertical distance of any center above the line or village indicates the number of nonproducers at that center, and hence is directly proportional to the amount of tribute which that center controls. (1981:331)

Estimates are felt to be conservative because they assume that all people living at a (noncenter) village are producers. It also measures only the tribute retained by the center, not the “usually small” fraction of tribute that is redistributed (1981:332).

While scholars in the area debate aspects of the formulation (Finsten et al. 1983; Hirth 1984; Steponaitis 1983, 1984), Steponaitis pioneered the use of formal models in the study of the political economy of chiefdoms, and his constructs have been highly influential.

Charles Spencer (1982a,b, 1987, 1990) has formally modeled the regulatory processes involved in the exchange of wealth items and prestige goods. Spencer (1982a) formulated a model for the demand for two sets of prestige goods in two chiefdoms. His model refers to equivalencies in value and demand for wealth items, and finds “that an interregional elite exchange system will maintain equilibrium as long as there are no prolonged disparities in the growth rates of the elite populations of the participating regional systems” (1982a:55). If such a disparity develops, he argues that the chiefdom undergoing expansion will receive relatively fewer prestige goods than will the stable system, and the expanding polity will flood its neighbor with prestige items (1982a:56). Based on the outcomes of these formal models, Spencer derives a series of detailed hypotheses (1982a:58–78) for testing using data from Cuicatlán Cañada in the Oaxaca valley, Mexico.

Spencer (1982b, 1998) examines chiefly political economies in cybernetic terms (Miller 1965a–c), specifically casting the model in terms of dissipative structures (Prigogine et al. 1977; Nicolis and Prigogine 1977; Zeleny 1980; Schieve and Allen 1982; Dyke 1988). Essentially his model is a formal restatement of the regulatory approach to chiefdoms (Wright 1977, 1984). Unlike the model in Cuicatlán Cañada (1982a), this model deals not only with the exchange of wealth objects between neighboring elites but the political economy of the system itself.

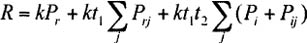

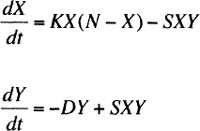

Spencer’s model involves several assumptions, including (1) elites and commoners can be treated as mathematically distinct units, (2) political growth is a logistical process but (3) regulatory transformation is not, and (4) the operation of the chiefly establishment results in the continual dissipation of energy. With these assumptions, he posits:

Where X = the amount of disposable resources controlled by the commoners, Y = the amount of disposable resources controlled by the elite, K = the rate of resource extraction by the commoners, D = the rate of resource dissipation by the elite, N = the total amount of extractable resources within the political economic territory of the system, and S = the tribute rate, or the fraction of commoners’ resources transferred to the elite (1982b:30). Spencer argues that the overall transfer term (SXY) will increase in direct proportion to both X and Y both because as X increases there are more resources available for transfer, and because as Y increases the ability of elites to demand more goods also increases. When the system reaches or approaches equilibrium, the ratio between disposable resources controlled by elite and controlled by commoners can be expressed as:

Spencer points out several characteristics of this relationship (1982b:31). First, political growth is favored by high rates of resource extraction by commoners K and a large quantity of resources available for extraction N. Political growth is discouraged by high rates of dissipation of resources by the elite D, particularly if this rate is greater than the tribute rate S.

At the same time, however, political growth itself leads to increasing values for elites’ resource dissipation D, but if other variables do not show similar rates of growth the system goes into decline (Spencer 1982b:31). Spencer sees only three ways to avoid this pitfall: (1) increase the rate of expropriation of resources from the commoners, (2) increase the rate of production, or (3) increase the total quantity of available resources.

Each option has associated risks and costs. Territorial expansion has the usual near-term risks associated with expansionary politics but is risky at the systemic level because it often involves a decrease in regulatory efficiency. The optimal size for a chiefdom is a radius of a half day’s travel (Spencer 1982a:6–7, 1982b:7–8, 1987:375; Helms 1979:53), and expansion beyond this scale both increases the risk of fragmentation and increases overall regulatory costs.

Intensifying production has practical limits, as does increasing the tribute rate. As a regulatory strategy, increasing demands on commoners poses the risk of disaffection. Asking for more of what is produced (S) or for the same fraction of a larger pie (K) is a strategy promising short-term benefits but long-term problems, especially as a means of regulating a system which inherently tends to need adjustment. Spencer’s model predicts that political expansion would contrarily lead to political decline, a constant feedback creating a kind of red queen’s race, where the political players have to run harder and harder just to stay where they are:

The productive base could become so overworked through intensification that yields would begin to fall off. Commoners could find themselves having to choose (especially in lean years) between loyalty to the chief and nutritional deprivation. Surplus demands might be increasingly perceived as onerous; disenchantment could sprout, allegiance wane, rebellion fester. (Spencer 1982b:33)

For Spencer, the solution was political expansion. Since this would overtax the regulatory mechanisms of the chiefdom, a regulatory transformation was forced, leading to the adoption of a different set of regulatory mechanisms consonant with state-level organization (1982b:34–38). Key to this regulatory change was increasing internal differentiation of control mechanisms, allowing delegation of authority with less opportunity for usurpation. The differential equations used for this are actually based on Nicolis and Prigogine’s (1977:459–461) model for the division of labor in ants.

Other scholars have focused on patterns in the collapse of chiefdoms. It has long been recognized (Sahlins 1963) that chiefdoms seem to have a characteristic growth-collapse pattern; in part this may reflect the coherence of power and authority in such organizational forms. Wright (1984) has argued that chiefly largesse is a direct barometer of the health of a mobilization economy. As local production falls off, producers divert more energy to producing comestibles and less to producing crafts. First the volume of craft items flowing upward would decrease, then the flow of staples. Chiefs would be less able to exhibit generosity to followers and obtain exotic goods from far away, signaling both internal and diplomatic failures and triggering some kind of adjustment—chiefly reforms, diversionary wars on neighbors, rebellion, or collapse.

Tainter (1988) argues that the costs of maintaining hierarchical control structures increase over time; hierarchies require increased investments to maintain the status quo (1988:195). The benefits of maintaining these structures do not similarly increase, so hierarchies eventually reach a balance point between the declining marginal returns on investments in maintaining the hierarchy and its increasing cost. At that point the hierarchy collapses into a series of less complex, less costly forms (1988:191–192, 25–31; Yoffee and Cowgill 1988).

Barker (1999) suggests that cycling reflects instability caused by conflicting needs between the domestic and political economies. Barker identifies an archaeological signature for redistributive buffering and argues that the political economy depends on the control of marginal surpluses controlled through the mobilization of tribute. One requisite use of tribute, however, is bankrolling producers in times of need. As this support comes to be expected, however, the amount of marginal surplus available to chiefs decreases, based on Chayanovian theory, creating instability as chiefs either reduce the surplus available for circulation (as comestibles or crafts) to the elite (leading to rebellion by the elite) or try to intensify tribute collection (leading to insurrection by commoners). He argues that the role of real or notional forms of redistributive buffering may have been central to the emergence of chiefs but remained dependent on the mobilization of marginal surpluses created by households. The legitimation and institutionalization of buffering mechanisms to support households in times of need would have unintentionally suppressed the production of these marginal surpluses, so that the same processes leading to the emergence of chiefs may have simultaneously created the conditions for recurrent chiefdom collapse. In the case of redistributive buffering, collective and individual interests converge, so that political or managerial approaches differ less in observable effect than in imputed motivation. Redistributive buffering is not only a means of protecting against economic want, but a regulatory strategy that allows leaders to guard against political challenge by controlling the availability of surpluses to potential rivals. It is difficult to identify the primacy of one or the other archaeologically because they should result in the same behaviors.

A somewhat different approach is articulated by David Anderson, based on his examination of cycling in the prehistoric Savannah River basin. He suggests that cycling partly reflects long-term successional dynamics linked to matrilineal inheritance of positions of rank and matrilocal postmarital residence among Mississippian elites (1990a:136–142; 1990b:200–202), in concert with a complex set of related factors, including environmental stress (1990a:536–559; Anderson et al. 1995). Anderson argues that these factors combine to create a high potential for challenge from within the ruler’s own kin group. Anderson’s studies are of special interest because he and his colleagues used tree ring data to monitor environmental fluctuations, relating periods of stress and plenty to changes in organizational behavior and suggesting the scales of storage necessary for chiefs to bankroll their communities to avoid economic and political collapse.

Some scholars would argue that it is instead the concept of chiefdom that has collapsed, weighed down by too much theoretical baggage and representing too great a range of social and political variation. Feinman and Neitzel (1984), for example, examined a cross-cultural sample of prestate sedentary New World societies and found remarkable variability in organizational form:

No simple modal patterns were present. Instead the observed variation was multidimensional and continuous. No single value for any attribute characterized each case nor could the state of a particular variable be used to predict the values of all other attributes. Because each variable represents a specific organizational dimension, it would be a mistake to focus on any one attribute as a general indicator of societal complexity.

Overall, they found leadership positions in all middle-range societies (1984:56) but recorded enormous variation in the functions and prerogatives of leadership positions. There was, however, relatively strong agreement between the degree of political differentiation recorded and the number of decision-making levels present (1984:64).

Leonard and Jones (1987:207–210) separately found no tendency for the cases in Murdock’s Ethnographic Atlas (1967) to form clusters of traits corresponding to proposed taxonomic stages. O’Shea and Barker (1996:16–21) examined a series of dimensions of political differentiation for ethnohistoric and prehistoric cases, concluding that taxonomic classifications both suppressed variability and masked different rates of change along each dimension.

While these studies suggest that dimensions of social and political differentiation can vary independently, it has also become increasingly clear that rising chiefdoms in different parts of the world seem to follow distinct cultural trajectories, each of which must be understood as occurring within a unique set of historically contingent circumstances. (Earle 1987:281–288 provides a useful overview of chiefdoms studies by area.) In North America, for example, there are significant differences in both the empirical courses toward complexity and their theoretical treatment between, say, the Black Warrior valley chiefdom centered at Moundville (Peebles 1987, 1983, 1978, 1971; Powell 1988; Knight and Steponaitis 1998; Steponaitis 1991, 1983, 1978; Welch 1986, 1990, 1991; Welch and Scarry 1995) and the American Bottom chiefdom centered at Cahokia (Milner 1998, 1990; Peregrine 1992; Saitta 1994; Pauketat 1991, 1992, 1994, 1997; Pauketat and Emerson 1991; Kelly 1991a,b; Stoltman 1991; Emerson 1991; Dincauze and Hasenstab 1989; Bareis and Porter 1984; cf. Knight 1997; Muller 1997). It is possible that these patterns reflect real differences in pathways toward complexity, and that the popularity of different approaches indexes their applicability to the case at hand. Identifying and monitoring real regional differences in cultural trajectories would be a significant step forward, allowing recognition of both empirical variability and the contingency of social processes.

Then again, these theoretical differences may tell us less about prehistoric societies than their modern students. Due to the vagaries of the archaeological record—and our imperfect knowledge of it—some theoretical approaches may be easier to apply to the kinds and qualities of data known within specific traditions of research. These traditions in turn create their own problem-oriented data sets, so that the archaeological data are inflected by the theoretical perspectives employed. It is also intriguing that while Polynesia played an important role in the development of the concept of chiefdom, and in challenges to the central role of redistribution in its formulation, detailed analyses by Patrick Kirch and his colleagues suggest that the complexity of the rise of Polynesian chiefdoms is poorly served by any single set of models, whether collectivist or individualist (Kirch 1984:282–283, 1994, 1990, 1988; Earle 1991, 1997).

Some scholars have optimistically concluded that there is an emerging consensus regarding the nature, origin, and operation of chiefdoms (Earle 1987:279). I would suggest—with equal optimism—just the opposite. I would point to increasing recognition of the empirical diversity of middle-range societies and increasing acceptance of diverse theoretical approaches to their study, to a lively and spirited debate over substantive issues, and to an emerging view of prestate hierarchical societies less as imperfect or diminutive states and more as a unique set of organizational forms worthy of study in their own right. And I would suggest that the chiefdom—that bastardized concept—is only now coming into its inheritance.

1. “Of its own kind” (editor’s note).

2. See also Goldman’s earlier (1960:694–711) separation of three grades of “status lineages,” explicitly modeled on Kirchoff’s (1955) analysis of conical clans.

3. “Essential condition” (editor’s note).

4. Of materialistic origin, hylomorphism is the doctrine that matter is the first cause of the universe (editor’s note).

5. Carneiro (1970) used the term “environmental circumscription” to refer to restrictions imposed by the surrounding environment, and “social circumscription” to restrictions imposed by surrounding populations (editor’s note).

6. “Leaderless” (editor’s note).

7. Items whose consumption is consistent with the lifestyles of chiefs and other elites (editor’s note).

8. See also Sahlins (1963). Clark and Blake provide a very different theoretical approach to the notion that big-man systems can, at least under certain circumstances, give rise to chiefdoms.

9. Although some scholars (Welch 1986, 1991) had previously concluded that chiefly economies can be understood in terms of a prestige-goods construct supplemented by an internal mobilization economy.

10. Hegemony is the dominant influence of one individual or social group over another (editor’s note).

Acher, J. 1906. Notes sur le droit savant au moyen âge. Revue Historique de Droit Français et Étranger 30: 125–176.

Anderson, David G. 1990a. Political change in chiefdom societies: Cycling in the late prehistoric southeastern United States. Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan.

———. 1990b. Stability and change in chiefdom level societies: An examination of Mississippian political evolution on the South Atlantic slope. In Mark Williams and Gary Shapiro, eds., Lamar archaeology: Mississippian chiefdoms in the Deep South, 187–213. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Anderson, David G., David W. Stahle, and Malcolm K. Cleaveland. 1995. Paleoclimate and the potential food reserves of Mississippian societies: A case study from the Savannah River valley. American Antiquity 60: 258–286.

Arendt, Hannah. 1958. The human condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bareis, Charles J., and James W. Porter (eds.). 1984. American Bottom archaeology. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Barker, Alex W. 1999. Chiefdoms and the economics of perversity. Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan.

Bascom, William R. 1948. Ponapean prestige economy. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 4: 211–221.

Blanton, Richard S., G. Feinman, S. A. Kowalewski, and P. N. Peregrine. 1996. A dual-processual theory for the evolution of Mesoamerican civilization. Current Anthropology 37: 1–14.

Blanton, Richard S., S. Kowalewski, G. Feinman, and J. Appel. 1981. Ancient Mesoamerica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brumfiel, Elizabeth M. 1976. Regional growth in the eastern valley of Mexico: A test of the “population pressure” hypothesis. In Kent V. Flannery, ed., The early Mesoamerican village, 234–249. New York: Academic.

———. 1994. Ethnic groups and political development in ancient Mexico. In Elizabeth Brumfiel and John Fox, eds., Factional competition in the New World, 89–102. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brumfiel, Elizabeth, and Timothy K. Earle (eds.). 1987. Specialization, exchange, and complex societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brumfiel, Elizabeth, and John W. Fox (eds.). 1994. Factional competition in the New World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carneiro, Robert L. 1967. On the relationship between size of population and complexity of social organization. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 23: 234–243.

———. 1970. Theory of the origin of the state. Science 169: 733–738.

———. 1978. Political expansion as an expression of the principle of competitive exclusion. In R. Cohen and E. Service, eds., Origins of the state: The anthropology of political evolution, 205–223. Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues.

———. 1981. The chiefdom: Precursor of the state. In G. D. Jones and R. R. Kautz, eds., The transition to statehood in the New World, 37–75. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 1988. Circumscription theory: Challenge and response. American Behavioral Scientist 31: 497–511.

———. 1990. Chiefdom-level warfare as exemplified in Fiji and the Cauca valley. In Jonathan Haas, ed., The anthropology of war, 190–211. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 1991. The nature of the chiefdom as revealed by evidence from the Cauca valley of Colombia. In A. T. Rambo and K. Gillogly, eds., Profiles in cultural evolution, 167–190. Anthropological Papers 85. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology.

———. 1992. Point counterpoint: Ecology and ideology in the development of New World civilizations. In A. A. Demarest and G. W. Conrad, eds., Ideology and pre-Columbian civilizations, 175–203. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.

———. 1998. What happened at the flashpoint? Conjectures on chiefdom formation at the very moment of conception. In E. M. Redmond, ed., Chiefdoms and chieftaincy in the Americas, 18–42. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Clark, John E., and Michael Blake. 1994. The power of prestige: Competitive generosity and the emergence of rank societies in lowland Mesoamerica. In E. Brumfiel and John Fox, eds., Factional competition in the New World, 17–30. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cooper, John M. 1941. Temporal sequence and the marginal cultures. Anthropological Series 10. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America.

———. 1942. Areal and temporal aspects of aboriginal South American culture. Primitive Man 15: 1–38.

Coquery-Vidrovich, Catherine. 1969. Recherches sur un mode de production africain. La Pensée 144: 61–78.

———. 1977. Research on an African mode of production. In P. C. W. Gutkind and P. Waterman, eds., African social studies: A radical reader, 77–92. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Cordy, Ross. 1981. A study of prehistoric social change in the Hawaiian Islands. New York: Academic.

Creamer, Winifred, and Jonathan Haas. 1985. Tribe versus chiefdom in lower Central America. American Antiquity 50: 738–754.

D’Altroy, Terence N., and Timothy K. Earle. 1985. Staple finance, wealth finance, and storage in the Inka political economy. Current Anthropology 26(2): 187–206.

Dincauze, D. F., and R. J. Hasenstab. 1989. Explaining the Iroquois: Tribalization on a prehistoric periphery. In T. C. Champion, ed., Centre and periphery, 67–87. London: Unwin Hyman.

Dunnell, Robert C. 1980. Evolutionary theory and archaeology. Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 3: 35–99.

Dyke, C. 1988. Cities as dissipative structures. In Bruce H. Weber, David J. Depew, and James D. Smith, eds., Entropy, information, and evolution: New perspectives on physical and biological evolution, 355–367. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Dyson, S. 1985. The creation of the Roman frontier. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Earle, Timothy K. 1973. Control hierarchies in the traditional irrigation economy of the Halelea District, Kauai, Hawaii. Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan.

———. 1977. A Reappraisal of redistribution: Complex Hawaiian chiefdoms. In T. K. Earle and J. E. Ericson, eds., Exchange systems in prehistory, 213–229. New York: Academic.

———. 1978. Economic and social organization of a complex chiefdom: The Halelea District, Kaua’i, Hawaii. Anthropological Papers 63. Ann Arbor: Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan.

———. 1985. Commodity exchange and markets in the Inka state: Recent archaeological evidence. In Stuart Plattner, ed., Markets and marketing: Proceedings of the 1984 Meeting of the Society for Economic Anthropology, 369–397. Monographs in Economic Anthropology 4. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

———. 1987. Chiefdoms in archaeological and ethnohistorical perspective. Annual Review of Anthropology 16: 279–308.

———. 1989. The evolution of chiefdoms. Current Anthropology 30: 84–88.

Earle, Timothy K. (ed.). 1991. Chiefdoms: Power, economy, and ideology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 1994a. Positioning exchange in the evolution of human society. In Timothy G. Baugh and Jonathon E. Ericson, eds., Prehistoric exchange systems in North America, 419–437. New York: Plenum.

———. 1994b. Wealth finance in the Inka empire: Evidence from the Calchaquí valley, Argentina. American Antiquity 59(3): 443–460.

———. 1997. How chiefs come to power: The political economy in prehistory. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Eisenstadt, S. N. 1959. Primitive political systems: A preliminary comparative analysis. American Anthropologist 61: 200–220.

Ekholm, K. 1972. Power and prestige: The rise and fall of the Kongo Kingdom. Uppsala: Skriv Service.

Ekholm, K., and Jonathan Friedman. 1985. Towards a global anthropology. Critique of Anthropology 5(1): 97–119.

Emerson, Thomas E. 1991. Some perspectives on Cahokia and the northern Mississippian expansion. In T. E. Emerson and R. B. Lewis, eds., Cahokia and the hinterlands, 221–236. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Feinman, Gary, and Jill Neitzel. 1984. Too many types: An overview of sedentary prestate societies in the Americas. Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 7: 39–102.

Finney, B. 1966. Resource distribution and social structure in Tahiti. Ethnology 5: 80–86.

Flannery, Kent V. 1972. The cultural evolution of civilization. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 3: 399–426.

Flannery, Kent V., and Joyce Marcus. 1999. Formative Mexican chiefdoms and the myth of the “mother culture.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 19: 1–37.

Fortes, Meyer, and E. E. Evans-Pritchard (eds.). 1940. African political systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frankenstein, Susan, and Michael Rowlands. 1978. The internal structure and regional context of early Iron Age society in southwestern Germany. Bulletin of the Institute of Archaeology, London 15: 73–112.

Fried, Morton H. 1967. The evolution of political society. New York: Random House.

———. 1975. The notion of tribe. Menlo Park, CA: Cummings.

Friedman, Jonathan. 1975. Tribes, states, and transformations. In Maurice Bloch, ed., Marxist analyses and social anthropology, 161–202. New York: Wiley.

Friedman, Jonathan, and Michael Rowlands. 1977. Notes toward an epigenetic model of the evolution of “civilisation.” In Jonathan Friedman and Michael Rowlands, eds., The evolution of social systems, 201–276. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Giddens, Anthony. 1984. The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gilman, Antonio. 1995. Prehistoric European chiefdoms: Rethinking “Germanic” societies. In T. Douglas Price and Gary M. Feinman, eds., Foundations of social inequality, 235–251. New York: Plenum.

Gledhill, John, and Michael J. Rowlands. 1982. Materialism and socio-economic process in multi-linear evolution. In Colin Renfrew and Stephen Shennan, eds., Ranking, resource and exchange: Aspects of the archaeology of early European society, 144–149. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goldman, Irving. 1960. The evolution of Polynesian societies. In S. Diamond, ed., Culture in history: Essays in honor of Paul Radin, 687–711. New York: Columbia University Press.

———. 1970. Ancient Polynesian society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Halstead, Paul, and John M. O’Shea. 1982. A friend in need is a friend indeed: Social storage and the origins of social ranking. In Colin Renfrew and Stephen Shennan, eds., Ranking, resource, and exchange: Aspects of the archaeology of early European society, 92–99. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Halstead, Paul, and John M. O’Shea (eds.). 1989. Bad year economics: Cultural responses to risk and uncertainty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harris, Marvin. 1979. Cultural materialism: The struggle for a science of culture. New York: Random House.

Haselgrove, Colin. 1987. Culture process on the periphery: Belgic Gaul and Rome during the late republic and early empire. In Michael Rowlands, Mogens Larsen, and Kristian Kristiansen, eds., Centre and periphery in the ancient world, 125–139. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hayden, Brian, and Rob Gargett. 1990. Big man, big heart? A Mesoamerican view of the emergence of complex society. Ancient Mesoamerica 1: 3–20.

Helms, Mary. 1979. Ancient Panama: Chiefs in search of power. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

———. 1988. Ulysses’ sail: An ethnographic odyssey of power, knowledge, and geographical distance. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Herskovits, Melville J. 1940. The economic life of primitive peoples. New York: Knopf.

Hocart, A. M. 1936. Kings and councillors: An essay in the comparative anatomy of human society. Cairo: Printing Office Paul Barbey.

Hodder, Ian. 1986. Reading the past: Current approaches to interpretation in archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hodder, Ian (ed.). 1982. Symbolic and structural archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson, A. W., and T. K. Earle. 1987. The evolution of human society: From foraging group to agrarian state. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Johnson, G. A. 1982. Organizational structure and scalar stress. In C. Renfrew, M. J. Rowlands, and B. A. Seagraves, eds., Theory and explanation in archaeology: The Southampton Conference, 389–421. New York: Academic.

Junker, Laura. 1990. The organization of intra-regional and long-distance trade in pre-Hispanic Philippine complex societies. Asian Perspectives 29: 29–89.

———. 1994. Trade competition, conflict, and political transformation in sixth-to-sixteenth-century Philippine chiefdoms. Asian Perspectives 33: 229–260.

Keegan, William F., and Morgan D. Maclachlan. 1989. The evolution of avunculocal chiefdoms: A reconstruction of Taino kinship and politics. American Anthropologist 91(3): 613–630.

Kehoe, Alice B. 1981. Bands, tribes, chiefdoms, states: Is service serviceable? Paper presented at the 46th Society for American Archaeology Meeting, San Diego, California.

Kelekna, Pita. 1998. War and theocracy. In E. M. Redmond, ed., Chiefdoms and chieftaincy in the Americas, 164–188. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Kelly, John E. 1991a. Cahokia and its role as a gateway center in interregional exchange. In T. E. Emerson and R. B. Lewis, eds., Cahokia and the hinterlands, 61–80. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

———. 1991b. The evidence for prehistoric exchange and its implications for Cahokia. In J. B. Stoltman, ed., New perspectives on Cahokia: Views from the periphery, 65–92. Madison, WI: Prehistory.

Kipp, Rita Smith, and Edward M. Schortman. 1989. The political impact of trade in chiefdoms. American Anthropologist 91: 370–385.

Kirch, Patrick V. 1984. The evolution of the Polynesian chiefdoms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 1988. Long-distance exchange and island colonization: The Lapita case. Norwegian Archaeological Review 21: 103–117.

———. 1990. The evolution of socio-political complexity in prehistoric Hawai’i: An assessment of the archaeological evidence. Journal of World Prehistory 4: 311–345.

———. 1994. The wet and the dry: Irrigation and agricultural intensification in Polynesia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kirch, Patrick V., and R. C. Green. 1987. History, phylogeny, and evolution in Polynesia. Current Anthropology 28: 431–456.

Kirchoff, Paul. 1955. The principles of clanship in human society. Davidson Journal of Anthropology 1: 1–10.

Knight, Vernon James. 1990. Social organization and the evolution of hierarchy in southeastern chiefdoms. Journal of Anthropological Research 46: 1–23.

———. 1997. Some developmental parallels between Cahokia and Moundville. In T. R. Pauketat and T. E. Emerson, eds., Cahokia: Domination and ideology in the Mississippian world, 229–268. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Knight, Vernon James, and Vincas P. Steponaitis (eds.). 1998. Archaeology of the Moundville chiefdom. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Kohl, Philip L. 1987. The use and abuse of world-systems theory: The case of the pristine west Asian state. Advances in Archaeological Method Theory 11: 1–35.

Leonard, Robert D., and George T. Jones. 1987. Elements of an inclusive evolutionary model for archaeology. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 6: 199–219.

Lewis, I. M. 1959. The classification of African political systems. Rhodes-Livingstone Journal 25: 59–69.

Linares, Olga F. 1977. Ecology and the arts in ancient Panama: On the development of social rank and symbolism in the central provinces. Studies on Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology 17. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks.

McGuire, Randall H. 1983. Breaking down cultural complexity: Inequality and heterogeneity, Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 6: 91–142.

———. 1992. A Marxist archaeology. San Diego: Academic.

Meek, Ronald L. 1976. Social science and the ignoble savage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Miller, James. 1965a. Living systems: Basic concepts. Behavioral Science 10(3): 193–237.

———. 1965b. Living systems: Structure and process. Behavioral Science 10(4): 337–379.

———. 1965c. Living systems: Cross-level hypotheses. Behavioral Science 10(4): 380–411.

Milner, George R. 1990. The late prehistoric Cahokia cultural system of the Mississippi River valley: Foundations, florescence, and fragmentation. Journal of World Prehistory 4: 1–43.

———. 1998. The Cahokia chiefdom. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Mitchell, J. Clyde. 1956. The Yao village: A study in the social structure of a Nyasaland tribe. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Muller, Jon. 1997. Mississippian political economy. New York: Plenum.

Murdock, George P. 1967. Ethnographic atlas. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Nicolis, G., and Ilya Prigogine. 1977. Self-organization in non-equilibrium systems: From dissipative structures to order through fluctuations. New York: Wiley.

Oberg, Kalervo. 1940. The Kingdom of Ankole in Uganda. In M. Fortes and E. E. Evans-Pritchard, eds., African political systems, 121–163. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. 1955. Types of social structure in lowland South America. American Anthropologist 57: 472–487.

O’Shea, John M., and Alex W. Barker. 1996. Measuring social complexity and variation: A categorical imperative? In Jeanne Arnold, ed., Emergent complexity: The evolution of intermediate societies, 13–24. International Monographs in Prehistory, Archaeological Series 9. Ann Arbor, MI.

Pauketat, Timothy R. 1991. The dynamics of pre-state political centralization in the North American midcontinent. Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan.