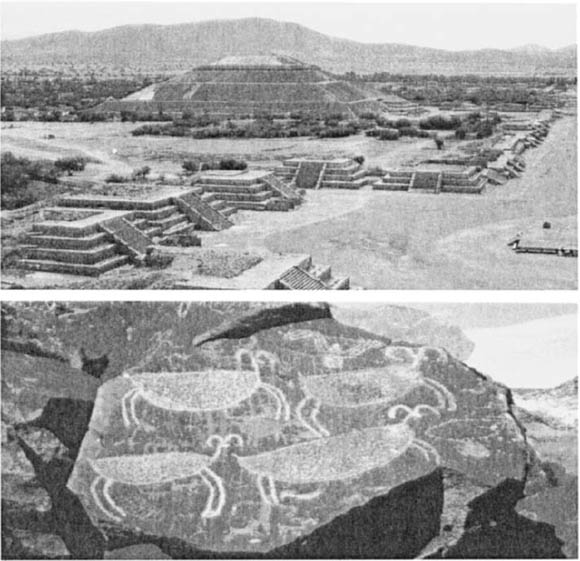

FOR ARCHAEOLOGISTS, ESPECIALLY prehistoric archaeologists, religion has been a problem. All cultures have a religion, but few archaeologists have known what to do analytically with this fact.1 A common result has been to either rationalize away religion as “adaptive” and then dismiss it from further consideration, or treat it solely in descriptive terms, usually based on unrecognized analogies with Western Judeo-Christian religious traditions. Both approaches are inadequate for a holistic or sophisticated reconstruction of social life. Even though religion may not be important in the lives of many, perhaps most, archaeologists, it was, incontestably, a central factor in the lives of prehistoric peoples. It was a primary constituent of their culture and was heavily intertwined in the organizational structure of their society. A prehistoric site like Teotihuacan, Mexico, where religious architecture dominates not only the site but the regional landscape, demonstrates this fact in a direct fashion (figure 31.1).

The traditional archaeological reticence to study prehistoric religion has started to recede, with an impressive number of recent papers and books on this topic.2 In this chapter I discuss some of the analytical approaches that archaeologists take to studying prehistoric religion. It is useful, however, to start with some working definitions. These provide a guideline to the general characteristics and attributes of religions, since we need to have an explicit understanding of this phenomenon we call religion if we are to study it in a rigorous way. Next I discuss the intellectual trends that have implicitly shaped our views of this phenomenon. This promotes an understanding of how religion has been studied and of what future directions will be most profitable. I then turn to the recent approaches themselves and provide suggestions for thinking about and interpreting acts of faith in the past.

Figure 31.1. Are prehistoric religion and ritual archaeologically invisible? Though many archaeologists implicitly hold this belief, sites from large-scale urban civilizations, like Teotihuacan, Mexico (a), as well as ones created by the nomadic Great Basin Shoshone hunter-gatherers, like Big Petroglyph Canyon, Coso Range, California (b), challenge this view. In both cases, religious remains are, by a wide measure, the most visible aspects of the regional archaeological records. (Photos by David S. Whitley)

Even while many archaeologists ignore or pay minimal heed to prehistoric religion, they carry strong implicit attitudes about what religions are, how they work, and what purpose they serve. Almost invariably, these presuppositions are based on their own Judeo-Christian upbringings. Not only are these commonsense ideas about religion usually wrong (especially when we move from contemporary world religions to traditional, non-Western small-scale ones) but the implicit, essentialist biases they reflect—all religions are the same, and they are just like the one we grew up with—greatly problematize the archaeological analysis of religious phenomena.

A simple but fundamental example of the kind of confusion engendered by this implicit bias concerns the basic question of why religion is a cross-cultural universal. A common response emphasizes personal comfort linked to social control: religions promise eternal salvation to those who follow the proper moral strictures. While these attributes are certainly present in Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism, many religions neither concern themselves with salvation nor link the fate of the soul to a moral reckoning (Boyer 2001). The cross-cultural empirical facts here are very clear: salvation and the emotional comfort it putatively affords along with the social control that results are inadequate universal explanations for religion, despite the frequency with which these features are cited as the “obvious” answer to this question. Understanding and analyzing prehistoric religion, in other words, requires a much deeper comprehension of the ethnography of world religion than we may have absorbed in our childhood Sunday school classes. A good starting place is the various terms used in discussions of prehistoric religion.

Religion may be defined as “any shared set of beliefs and actions appealing to supernatural agency” (Whitehouse 2004:2). Religions include a cosmology, which is a theory of the origin, structure, and operation of the universe and the place of humans within it. Religions also include rituals or ceremonies. Brian Hayden (2003:459) defines rituals as “any formal and customarily repeated acts performed according to religious law or social custom.” The implication is that certain rituals may not involve religion at all (e.g., a college graduation ceremony). Rituals are religious (as opposed to purely political, say, or academic) when they are directed to some level at supernatural agents: spirits or gods.

Religion is also distinct from ideology, which is a “body of doctrine, myth and symbolism of a social movement, often with reference to some political or cultural plan, along with the strategies for putting the doctrine into action” (Flannery and Marcus 1993:263). Correctly used, ideology pertains to politics or social relationships (including gender relations), not religion. While the two can be linked, for example, in systems of sociopolitical dominance and control (especially where religion and politics are homologous), ideology properly is not a substitute for religious beliefs. Cult is another term that is sometimes used by archaeologists more or less in place of religion. Strictly speaking, a cult is a sect or ritual subset of a larger religious system (some charismatic Christian groups qualify as cults in that they are offshoots of larger organized religions). Given that the term currently has negative social connotations, it probably should only be used when it is clearly justified; that is, when it is certain that the archaeological phenomenon under study is a variant of, or a ritual subgroup within, a larger religious system.

Religions normally include a code of moral and ethical precepts and behaviors; these may be implicit or may be formalized. While all religions have a particular moral, spiritual, and metaphysical worldview and sensibility, only some religions have a developed theology, which is a formally defined religious philosophy and theory. Members of cultures that lack this last feature—probably the majority of the world’s prehistoric cultures and peoples—may not recognize that they have a religion as such, because what we (as outsiders) recognize as their religious beliefs and practices are so deeply intertwined with all aspects of their way of life. Religion to them is not an institution or an organization; it is simply the way they live and how they view their world.

All religions, however, have myths. These are sacred histories (typically) of unknown authorship, usually including a creation story, involving the activities of supernatural agents, and sometimes pertaining to a period of time prior to the current world. Myths in the last case can be distinguished from folk tales, allegories, or fables, which may have supernatural agents as actors but also include contemporary humans. Myths commonly serve as the de facto warrant or charter for the existing status quo (e.g., a kinship system or a series of hunting taboos). For this reason they have a central educational function, especially in nonliterate societies. Importantly, though, the relationship of myth to ritual varies widely. In some cultures—including our own Judeo-Christian tradition—ritual commonly consists of a ceremonial reenactment of a mythic event (e.g., the Mass and the Last Supper). But ritual may have no direct relationship to myth in other cultures, and even the supernatural agents invoked in rituals may be entirely distinct from mythic actors (Whitley 2000).

There is a long history of anthropological research on world religions (Morris 1987), one result of which has been a variety of religious typologies. Probably the most common of these emphasizes a distinction between shamanistic versus priestly religions, with the significance of this distinction encapsulated in the catchphrase “priests talk to gods whereas gods talk to shamans.” The implication here is that shamanistic religions involve direct personal interaction with the supernatural world, achieved through a visionary or altered state of consciousness (ASC) experience. For this reason shamanistic religions tend to be personal and often idiosyncratic in form. Priestly religions, in contrast, emphasize the activities of trained ritual formulists, the correct repetition of prayers, and the proper enactment of rites, and they are, correspondingly, highly structured. Traditionally shamanism was thought to correlate with hunter-gatherer societies and priestly religions with settled farmers, with this distinction seen as evolutionary in nature.

There is good cross-cultural evidence that different kinds of religious systems correlate, to some degree, with societal scale and levels of sociopolitical complexity (Winkelman 1992). But the simple and invariant evolutionary equation of shamanism with hunter-gatherers and priestly cults with farmers is overly simplistic, for a number of empirical reasons. First, not all hunter-gatherer religions are shamanistic; many are totemic, that is, based on membership in social groups (such as kinship units) which often emphasize increase rituals rather than trance (Guenther 1999; Layton 2001). The shamanic versus priestly distinction then only accounts for some of the known ethnographic variability in religious forms.

The second reason involves the fact that shamanism has been found also to occur in both chiefdom and state-level societies (Freidel et al. 1993; Thomas and Humphreys 1994; Price 2002), while some hunter-gatherer cultures have priestly religions (Kroeber 1925:53–62). Indeed, as Whitley and Rozwadowski (2004) have observed, classic Siberian shamanism—widely argued to be the origin of shamanism and to reflect a kind of fossilized Paleolithic hunter-gatherer worldview—first appeared in Siberia about 3,000 to 4,000 years ago, among Bronze Age pastoralists. And even totemic religions can include shamanistic components, exemplified by Australian Aboriginal clever men or men of high degree (Elkins 1977). As Winkelman (1992) implies, the distinction between shamanistic versus nonshamanistic religions is sometimes a question of degree rather than kind, with elements of both systems common in many cultures. Even though certain religious systems can be empirically classified as shamanistic, totemic, or priestly (Winkelman 1992; Guenther 1999; Price 2001b), these typological distinctions are inadequate to address problems of evolutionary process, especially since they underrepresent ethnographic variability in religious forms.

Perhaps not surprisingly, then, recent anthropological research has emphasized alternative, empirically sounder religious classifications that are more amenable to questions of the cultural transmission of religion. One of these, known as the ritual form hypothesis, has been developed by Robert Lawson and Thomas McCauley (1990; McCauley and Lawson 2002). Another, the modes of religiosity theory, has been presented by Harvey Whitehouse (2000, 2004; Whitehouse and Laidlaw 2004). Both emphasize how cognitive processes have effected the structure of religions, and how religion originated as part of our evolutionary development. These theories hold great promise for archaeological studies of religion linked to scientifically (as opposed to humanistically) oriented research (Whitehouse and Martin 2004).

Religions and religious beliefs worldwide may at first seem limitless in diversity, but in actual fact they are restricted in expression, especially once they are viewed from the perspective of cognitive structures. As Pascal Boyer has emphasized:

the many forms of religion that we know are not the outcome of historical diversification but of constant reduction. The religious concepts we observe are relatively successful ones selected among many other variants . . . To explain religion we must explain how human minds, constantly faced with lots of potential “religious stuff,” constantly reduce it to much less stuff. (2001:32)

An archaeology of religion may face some difficult tasks and problems, but a limitless range of variation in practice and belief is not one of them.

Understanding the status of research on prehistoric religion benefits from clarification concerning four widespread, even if implicit, archaeological perceptions about this topic. The first is epiphenomenalism; the second is exceptionalism; the third concerns the attitude that prehistoric religion is archaeologically invisible; and the fourth involves the fear that religious beliefs are irrational, contributing to their analytical intractability. Like the essentialism that has resulted in the implicit use of the Judeo-Christian tradition as an analogue for many archaeologists’ understanding of all religions, these perceptions have also greatly influenced the study of prehistoric religion during the twentieth century.

For the vast majority of scientifically and processually oriented archaeologists, religion in general terms and related topics like art and belief have been considered epiphenomenal (Flannery and Marcus 1993:261). This means that they are secondary or derivative in origin, and therefore analytically irrelevant. Philosopher Mary Midgley calls epiphenomenalism the “steam-whistle theory of mind,”

which says that what happens in our consciousness does not affect the behaviour of our bodies . . . Our experience is just an epiphenomenon, which means idle froth on the surface, a mere side-effect of physical causes. Consciousness is thus an example—surely a unique one?—of one-way causation, an effect which does not itself cause anything further to happen. (2001:107)

As I have noted elsewhere (Whitley 1998a:303), epiphenomenalism is an absurd doctrine because its implications are so extreme: all that matters are the behaviors that lead to the intellectual products we create. Our analytical results, syntheses, explanations, interpretations, and theories are effectively meaningless, because as cognitive products they are epiphenomenal (Whitley et al. 1999:221; Midgley 2003:34–40). But if this were true, why would anyone bother with a discipline like archaeology, or any academic endeavor for that matter?

Epiphenomenalism has been a widespread presupposition of recent archaeology because it originates deep in our intellectual history, in the Enlightenment and René Descartes’s separation of mind and body (Damasio 1994), with its emphasis on the physical (materialist) aspects of human social life, thereby eschewing the mental (or idealist). But as Midgley (2003) has illustrated, epiphenomenalism is nothing more than a metaphysical belief, not a scientific fact, and its adoption creates an irreconcilable contradiction for any theory about human nature, let alone for academic practice.

A related misperception is that it is difficult to study prehistoric religion because of the nature of archaeology itself. Christopher Hawkes (1954) expressed this formally when he proposed an ascending ladder of inferential difficulty, with diet, technology, and economy toward the bottom as the most animal-like and easiest aspects of prehistory to reconstruct, and religion and ideology, the most difficult, at the top. A half century later, the putative veracity of Hawkes’s model continues to be accepted by many archaeologists (Trigger 1989:395).

The problem with this perspective is twofold. First, it is circular: archaeologists cannot study religion effectively (as Trigger suggests) because, as our history of research putatively illustrates, they have not done so. Second, it reflects another implicit intellectual bias which treats archaeology as somehow different from the rest of science. But as Midgley (2001, 2003) has shown, religion has been ignored by all of the sciences since the Enlightenment because scientific thought was then in competition with religious belief. Science was the alternative to religion, and this caused scientists to ignore it. Even today, many (if not most) scientists are atheists or strong agnostics, with outwardly dismissive attitudes toward religion. Archaeology has ignored religion not primarily for methodological or empirical reasons, as Hawkes (1954) and many others have suggested, then, but for historical ones: the sciences have paid little attention to it since, as rational scientists, we inherited a bias against it.3

Many archaeologists likewise have assumed that prehistoric religion is (practically speaking) archaeologically invisible. As Higgs and Jarman (1975:1) observed (perhaps tongue in cheek), “The soul leaves no skeleton.” But this assertion is confused about the key methodological issue. Religion, including belief, is a cognitive phenomenon, but religion is expressed in human behavior. This behavior is archaeologically visible in the remains of ritual, in religious architecture, and in art and iconography. Indeed, hunter-gatherer religious behavior, in the form of rock art, is often the most visible aspect of the forager archaeological record. Ethnologist Dan Sperber notes:

It is a truism—but one worth keeping in mind—that beliefs cannot be observed. An ethnographer does not perceive that the people believe this or that; he infers it from what he hears them say and sees them do. (1982:161; emphasis added)

The implication here is that the ethnologist’s and archaeologist’s tasks in reconstructing beliefs are conceptually similar: both look at patterns of behavior and both infer meaning from these patterns (Geertz 1973:17). Contrary to what Higgs and Jarman (1975) apparently would like us to believe, the archaeology of religion is in certain respects little different, methodologically, from ethnology. Inasmuch as the archaeology of religion looks to behavioral remains, it is likewise methodologically similar to prehistoric interpretation and reconstruction more generally.

The widespread Enlightenment bias against religion causes many researchers to dismiss belief and ritual as necessarily irrational, therefore arbitrary, and effectively not understandable in any coherent sense. But this is simply not true, as the quotation above from Boyer emphasizes. Sahlins (1985:xiii) has observed that “the symbolic system is highly empirical.” Horton (1976, 1982) similarly has noted that many traditional thought systems are inductively and deductively logical, similar to our own. And, as I have illustrated previously (Whitley 1994a,b), religious symbolism in fact is often very coherent because of its common foundation in natural models:

These are natural phenomena, like animal behavior, that served to structure the logic underlying aspects of religious symbolism and ritual, usually by some form of analogical reasoning. In this sense, the thought underlying these models is rational and systematic. When natural models are based on phenomena that themselves involve invariant principles, uniformitarian laws, or timeless characteristics, the models have the potential to inform our understanding of truly prehistoric religious phenomena, without benefit of informants’ exegesis, and sometimes even without ethnohistorical connections. (Whitley 2001:132–133)

The idea that religious belief and practice are necessarily arbitrary and irrational, and therefore nearly impossible to see or study archaeologically, is, again, a reflection of our inherited Enlightenment bias against religion, not a circumstance resulting from empirical reality. As is also clear, religion is a cross-cultural universal and, as recent events in the Middle East demonstrate, it is deeply implicated in social and cultural processes that profoundly influence human lives. Joyce Marcus and Kent Flannery (1994) appropriately remind us that adequate archaeological reconstructions require a consideration of religion and ideology, just as they also must include a reconstruction of subsistence, economy, and technology.

It is hardly news to practicing archaeologists that, professionally speaking, we are data obsessive. One result is the apparent division of the discipline into data-based subdisciplines: ceramics, lithic analysis, paleoethnobotany, and so on. This kind of division can be seen within the archaeology of religion where, for example, we have specialized studies in mortuary remains (Scarre 1994; Carr 1995; Parker Pearson 1999), including even human sacrifice (Sugiyama 1989; Jelinek 1990; Shelach 1996; Bourget 2001; Boric and Stefanovic 2004). Monuments and sculptures too are frequently studied (Stone 1983; Bradley 1998), as well as art and iconography more generally (Pasztory 1974; Reilly 1991), including rock art (David 2002; Rozwadowski 2004; Keyser 2004). Ritual landscapes have also become a recent concern (Bradley 2000; Kirch 2004; Mathews and Garber 2004), along with the conceptually related interest in archaeoastronomy (Tate 1986; Freidel et al. 1993). There are also crosscutting topical specializations involving specific religious systems, such as Islam (Insoll 2003), Hinduism (Lahiri and Bacus 2004), Buddhism (Fogelin 2005), and shamanism (Price 2001a). While these distinctions are useful, an overview of prehistoric religious research is best seen from the perspective of the methodological approaches that underpin the analyses within these empirical and topical specializations. I start with the most fundamental of these approaches. This concerns the issue of identifying ritual evidence in the archaeological record.

The Visibility of Ritual and the Meaning of Ritual Remains

I noted above the traditional archaeological bias against studies of prehistoric religion. This derives from a series of confusions, including the idea that religion is difficult to identify in the archaeological record (Higgs and Jarman 1975), and that it is also the hardest aspect of human social life to reconstruct (Hawkes 1954). Although there is an understandable empirical plausibility to both notions (Renfrew 1985, 1994; Brown 1989; Kunen et al. 2002), they involve the flawed perspective that sets religion apart from other aspects of social life.

The key point here is that, with the recognition of a need for middle-range theory in archaeology (Binford 1977), prehistorians have confronted the fact that the significance and meaning of all aspects of the archaeological record are far from self-evident. Although our data result from human behavior, factors such as taphonomy and cultural disposal patterns result in an indirect record of human action.4 It is true, then, that the identification of ritual and the interpretation of ritual remains in some cases can be difficult archaeological problems. But, as the recognition of the need for middle-range theory has shown, this is a widespread archaeological problem, not one stemming from the nature of religious behavior itself (Cowgill 1993).

Researchers have taken four general approaches to middle-range research in the archaeology of religion: ethnographic analysis, ethnoarchaeology, an analysis of artifact life histories, and neuropsychology. I discuss the first three here, reserving the fourth for separate discussion below.

Ethnography is defined as the written accounts of ethnological studies (Layton 2001); ethnographic analysis in this case consists of synthesizing, summarizing, and interpreting existing anthropological research pertinent to the prehistoric religious phenomenon of interest. Ethnographic analysis is essential because, first, we often lack a cross-cultural understanding of traditional non-Western ritual practice and, second, we often implicitly assume that our general understanding of Judeo-Christian traditions applies in all cases, resulting in an essentialist interpretation of prehistory, in which all religions are like our own.5 In fact, as William Walker (2002) has emphasized, this conceptual problem goes beyond religious behavior to all aspects of human behavior. Archaeological research and interpretation are typically guided by what he refers to as practical reason: the commonsense idea that most archaeological remains can be understood in terms of economic, technological, or subsistence activities, ultimately because we view these as the primary determinants of our own behavior and social lives. As rational, twenty-first-century scientists who do not include religion in our lives, we implicitly assume the same about the prehistoric past. But ethnography tells us that religion is an important component of traditional societies that has often been embedded in all aspects of social life and consequently in many aspects of the archaeological record.

Ethnographic analyses ultimately oriented toward an understanding of the archaeological record are common in rock art research (Lewis-Williams 1981; Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1989; Conway and Conway 1990; Whitley 1992a, 2000; Rajnovich 1994; Layton 1992, 2001; Keyser and Klassen 2001; Francis and Loendorf 2002; Sundstrom 2004). In most of these studies the intent specifically has been to define the origin and meaning of corpora of art using a directly relevant regional or tribal ethnographic record. But ethnography has an importance far beyond any single study or region:

This is because . . . ethnography gives us a ballpark within which the plausibility of any particular . . . interpretation can be gauged. Put another way, ethnography provides a series of competing hypotheses which can be evaluated for any given empirical case. And while there is no reason to assume that every prehistoric example will necessarily conform to the origin and meaning of the ethnographic ones, at first glance we may assume that a prehistoric case should be reasonably close to the known range of variation in the ethnography. Alternatively, if the origin and meaning of a prehistoric case is thought to be significantly divergent from known ethnographic cases, then it is equally important to show how it diverges, why these variances might matter, and what unusual evidence supports this exceptional variation and interpretation. (Whitley 2005:86)

Reflecting this sentiment, George Cowgill has suggested that archaeology in general needs to pay more “attention to [any] ethnographic and historical data that are possibly relevant.” But, as he is also quick to add, “We also need to become more sophisticated in their use” (1993:561). One key here is the recognition that ethnographic data are just that: raw data. That is, they are typically neither full explanations nor complete interpretations, as many archaeologists assume. Instead, they consist of evidence that, like other data in the archaeological record, must be synthesized, analyzed, and interpreted. Detailed discussions of ethnographic analysis are provided by Layton (2001) and Whitley (2005) and, while these are directed toward rock art, they are broadly applicable to research on the archaeology of religion.

The ethnographic record, unfortunately, often does not emphasize the kinds of material cultural remains that lie at the heart of archaeological research, and it cannot for this reason resolve all of the questions an archaeologist of religion might pose. Researchers have turned to ethnoarchaeology to bridge this gap. Though not all archaeologists share my definition (e.g., the definition contained in Oswalt 1974 is broader), I use “ethnoarchaeology” to indicate ethnological studies directed toward an understanding of the material cultural record that constitutes our archaeological data, that is, research involving primary anthropological fieldwork rather than the analysis of written records alone. While ethnoarchaeology is now a respectable component of archaeological research, with only a few exceptions (Crystal 1974) it initially ignored religious phenomena in favor of economics, technology, and subsistence. But the scope of ethnoarchaeological research has broadened recently to include ritual stone use (Hampton 1999), landscape symbolism (Jordan 1999, 2003), and similar topics (Walter 1999; Kuznar 2001; Zedeño and Hamm 2001), and thus to contribute to an inferentially sounder archaeology of religion.

The potential value of ethnoarchaeological research is illustrated in a simple example involving Monument 3 at the Prehispanic site of El Baul, on the Pacific slope of Guatemala (figure 31.2). Sculptural monuments such as this are the focus of much Mesoamerican research, for understandable reasons. But beyond iconographic and/or hieroglyphic analysis, archaeological fieldwork commonly emphasizes excavation immediately at and under these monuments, in order to identify dedicatory offerings or other evidence that might clarify their age. While such information is obviously valuable, it provides little data concerning any potential wider-ranging ritual use of the monuments, once they were put in place.

Figure 31.2. As for archaeology generally, the study of prehistoric religion still requires middle-range research involving basic issues such as the nature of ritual deposition processes. Prehispanic Monument 3, El Baul, Guatemala, continues to be used ritually by Maya Indians; the cut-stone altar in the foreground supports a charcoal layer from burned copal incense, and the surroundings of the monument are covered by a ritual discard scatter, providing an opportunity for ethnoarchaeological research on ceremonial monument use. (Photo by David S. Whitley)

Although El Baul Monument 3 dates to the Late Classic period (A.D. 600–900), contemporary Maya ritual use of this sculpture has been documented since 1925 (Ritzenthaler 1967), and it may extend back further. The ethnoarchaeological evidence for this use is shown in figure 31.3, a plan of the artifact scatter resulting from ongoing offerings and rituals, drawn in 1985. This scatter spreads outward from the front of the monument, creating a ceremonial zone that is about 1.5 meters wide by 3 meters long (partly marked by a lens of charcoal), with a larger primary discard zone that extends another meter in each direction. An almost identical ritual discard pattern was documented at nearby Monument 2 (Whitley, Maya shrine field notes, 1985). The relevance of the contemporary ritual discard pattern to archaeological contexts partly involves the issue of ethnographic analogy, discussed below. But here it can be noted that this example provides a model for what could potentially be expected in Prehispanic contexts, and what might be revealed by more extensive but finer-grained excavations than are usually undertaken to expose these monuments. In this case ethnoarchaeology provides a kind of guide useful for structuring fieldwork, in order to maximize the chance of uncovering and recognizing ritual deposits, and thereby better understanding the ceremonial behavior (if any) associated with these sculptures.

The identification of ritual deposits is a particular concern of William Walker (1995, 2002; Walker and Lucero 2000; Walker et al. 2000), who has developed an artifact life history approach to this problem. As noted above, Walker has illustrated the fact that “utilitarian behavioral assumptions” effectively eliminate any recognition of the material reality of ritual, contributing to its putative archaeological invisibility. His use of artifact life history models, which chart all of the various uses of artifacts, shows

how the organization of known behaviors affects the frequencies, physical properties, associations, and spatial locations of artifacts. These approaches to inference are particularly strong because they highlight ambiguity in archaeological evidence, thereby facilitating more precise explorations of the organization or structure of prehistoric activities. (2002:163)

Figure 31.3. Ritual discard scatter at El Baul, Monument 3. This scatter derives from the ritual use of copal incense (packaged in cane leaves) and candles, along with offerings consisting of sugar, chocolate, flowers, cigarettes, and rum. (Plan by David S. Whitley, July 1985)

The approach Walker advocates contradicts the Western tendency to conceptualize the world exclusively in terms of sacred versus profane. Promoted as universal by Emile Durkheim (1965), this opposition led to the incorrect idea that artifacts or locations are either religious or mundane (Barrett 1991; Whitley 1998c). In fact, substantial ethnographic evidence demonstrates that particular artifacts could be used for practical and ceremonial purposes, depending on context. For example, North American shamans sometimes used arrows in curing rituals, and arrows were left as offerings at sacred sites, even though they more commonly were used as weaponry. Similarly, rituals were frequently conducted in the middle of villages or within habitation structures, not only in set-aside ceremonial precincts, with the distinction between sacred and profane then reflecting a question of time, not space. Since the ritual significance of an artifact or a location can change over time, it is overly simplistic only to consider utilitarian or practical interpretations of them.

Walker’s emphasis on understanding the value of artifact life histories is implicitly well expressed by O. W. (Bud) Hampton in his ethnoarchaeological study of highland New Guinea. Referring to the importance of hierophony—the concept that an object can reveal its sacral quality to an individual yet retain its profane physical characteristics—Hampton emphasizes that

to improve our archaeological identifications of seemingly profane tool stones that are found in the archaeological record and our inferences of associated behavior, we must measurably advance our understanding of the sacred stone—the hierophanies—that are created from the profane and may be present in the same record. The missing link that prompts error in our interpretations is our incomplete understanding of the magnitude of hierophanies that are present in nonliterate cultural systems. (Hampton 1999:306)

Many sacred objects were first manufactured as mundane tools, and many ostensibly profane spaces were sometimes used as ritual locales. This is shown by the most practical of archaeological remains: food. Hawkes’s (1954) ascending ladder of inference places subsistence, the most animal-like of our behaviors, at its base. Yet food was frequently a central component of ritual (Gumerman 1994; Hastorf 2003), indicating that the significance and meaning of even this most mundane of items is contingent on cultural context. Understanding how, why, and when prehistoric remains, artifacts, and places transform into ritual objects and spaces is, then, an important problem for archaeologists of religion. Defining artifact life histories, themselves based on ethnographic and ethnoarchaeological research, reminds us that rigid traditional conceptualizations of artifacts in terms of categories such as ideotechnic versus technomic (Binford 1962) is overly simplistic, and unlikely to result in adequate prehistoric interpretations and explanations.

A second important issue in the archaeology of religion involves the use of the direct-historical approach (von Gernet and Timmins 1987; von Gernet 1993; Cowgill 1993; Marcus and Flannery 1994; Hill 1994; Huffman 1996; Brown 1997; Whitley et al. 1999). This in fact raises larger questions about the nature of change over time, especially change in religious systems, and the place of ethnographic analogy in archaeological research.

Although it has earlier intellectual roots, the direct-historical approach (DHA) was formally defined by Waldo Wedel (1938) in a classic study of North American plains prehistory. The DHA is based on the idea that the past can be understood by identifying continuities between it and known components of the ethnographic present, whether involving the function of specific artifact types, the operation of settlement systems, the nature of rituals, or the meaning of iconography. As is then clear, use of the DHA is ultimately linked to ethnographic analysis. But in archaeological practice the DHA involves identifying changes over time as much as tracing continuities (Marcus and Flannery 1994). This fact belies the slogan-type criticism that the DHA is simply a projection of the ethnographic present onto the past, in which case (as this criticism goes) what is the point of studying the prehistoric past?

As Tom Huffman (1986) has instead emphasized, change is an empirical condition that can be identified in the archaeological record. If we can identify prehistoric change archaeologically—and contemporary research is partly predicated on that conviction—then there is no necessary danger in judiciously using appropriate evidence from the recent past to interpret an older prehistory. Indeed, as Huffman (1996) has also shown, the DHA requires a recursive analytical relationship between the ethnographic and archaeological records, and this can also result in a clarification or rewriting of aspects of the ethnography.

Huffman’s (1986) use of the DHA provides a good illustration of this approach. It involves an interpretation of the southern African Great Zimbabwe culture (A.D. 1290–1450), in light of continuities with more recent Khami period (A.D. 1450–1800) ethnography and archaeology, linked to the contemporary Eastern Bantu-speaking Shona. His argument, graphically portrayed in figure 31.4, is relatively straightforward. Building on the ethnological research of Adam Kuper (1980), Huffman knew that Shona social organization and worldview (including elements of religious symbolism and ritual) were expressed in their settlement layout: the structure of the settlements reflected their social and cultural organization and logic. A systematic comparison of Khami and Great Zimbabwe period sites allowed him to identify substantial equivalencies in settlement structure and thus continuity between the prehistoric and historic pasts, supporting the inference that Great Zimbabwe period social organization and worldview were similar to the ethnographic Shona.

In the strict sense, the DHA involves use of a directly relevant ethnographic record, most commonly understood as the ethnography that is tied to the creators of a particular archaeological record. Who the contemporary descendants of these last individuals are, or (viewed from the other direction) identifying the prehistoric heritage of an indigenous ethnic group, is an increasingly contentious topic, exacerbated by repatriation, subtextual debates about ownership, and control of the past (Jemison 1997; Whitley 2001), and even the division of profits from tribal casinos. While there are a variety of related issues tied to this complicated topic, two are particularly important here. The first concerns the fact that ethnic affiliations and the ritual systems associated with them are not always as fixed as a Western scientific perspective might assume. These instead can change, especially when they are tied to economic advantage, as Jannie Loubser (1991) has illustrated in a southern African Venda case. Archaeological insistence on tying ethnicity and cultural heritage to one Western view of biological genealogy is, then, narrowly simplistic, particularly since the concept “descended from,” including our own Western scientific definition of this concept, is itself culturally determined (Nabokov 2002).

Figure 31.4. The logic of a direct-historical approach interpretation of Great Zimbabwe social organization and worldview, based on a comparison with recent Khami period ethnography and archaeology (from Huffman 1996:8).

The second issue involves the nature of prehistoric change in general terms, and change in religious systems specifically. As Loubser (2004) has noted, many archaeologists view change between the ethnographic present and the prehistoric past necessarily in catastrophic terms; that is, involving complete or nearly complete cultural discontinuity. This totally disregards the ethnographic record, and is somewhat inexplicable given our long use of “battleship-shaped” seriation curves, which demonstrate both that change in material culture is often gradual, and that change occurs at different rates. Apparently we are comfortable with this circumstance in truly prehistoric contexts, but less so for the recent past. Or maybe it seems acceptable for ceramics but not ritual and belief.6

Regardless, ethnologists likewise have shown that different traits or characteristics of culture change at different rates. Marshall Sahlins (1985) calls these “sites” of culture, noting that some such sites (like lithic assemblages) are prone to frequent and rapid historical action and thus change, but that this may have little if any correlation with change in other “sites” of culture. The impact on ritual of a change in subsistence patterns, for example, is not necessarily straightforward (Whitley 1994b). Religions in fact are fundamentally conservative (Steward 1955; Bloch 1974) and there is no a priori justification for assuming either that they necessarily have changed, due to the passage of time, or that change in a religion will necessarily correlate with changes in subsistence, environment, or technology.

As Robin Horton (1993) has illustrated, contemporary Western thought systems (including religions) are closed in the sense that they see other systems of thought as confused or false competitors; either you are a member of Religion X and you will therefore be saved, or you will suffer eternal damnation. Non-Western traditional thought systems, in contrast, are often open and syncretic: Culture Y’s god may be all-powerful but, when informed about Culture Z’s god, the people of Culture Y are happy to add her to its pantheon. The implication is that, even with cultural change and innovation, considerable continuity can still exist. Persistence is often as important over time as change when considering cultural dynamics.

Maurice Bloch (1986, 1992) has illustrated in detail how aspects of a ritual system will change as sociopolitical conditions shift. But the core of the ritual system will persist through these changes. The result is far different from either complete replacement or total stasis; instead it simultaneously involves continuity and change, operating at different scales at the same time, within the same ritual system. An archaeological example of this process involves change over time in the iconographic corpus of the Coso range, California, petroglyphs (Whitley et al. 1999; Whitley, in press). Following the definitions of Turner (1967) and Ortner (1973), this includes long-term continuity in the use of key or dominant symbols; in this case bighorn sheep and entoptic motifs. This continuity supports the use of the DHA in extending backward the ethnographic interpretation for the making and meaning of this art. But it has also identified changes in the use frequency of elaborating symbols; in this case highly decorated human figures. The resulting interpretation involves continuity in the general ritual system but change in aspects of this same system during specific times, due to historical circumstances.

Most prehistoric contexts lack the kinds of ethnographic connections required for the DHA. In these circumstances, ethnographic analogy may play an interpretive role. As Wylie (1985) has shown, much of our archaeological interpretation is based on analogy, even though this may be implicit and unrecognized, and we will only benefit from explicitly considering the methodological issues that its use raises. There are different kinds of analogies, with contrasting inferential strengths and analytical purposes. I distinguish three types. Functional analogies are based on invariant determining principles or universal processes, such as the functioning of the human body (Lewis-Williams 1991). We know, for example, that prehistoric human thought processes were similar to our own at the neurological level, because we share the same neural architecture. In certain cases (below), we can use this fact to make useful interpretations about archaeological evidence. Particularly strong inferences, potentially providing true explanations of human behavior, result when functional analogies are used.

Historical analogies are the kind typically used in the DHA, and they are based on descent and/or cultural associations. As noted above, many archaeologists apparently assume that the question of descent is an either/or problem, defined by their strict Western perspectives on ethnicity, cultural continuity, and genetics. The result is a highly restrictive use of the DHA or, more commonly, little or no explicit use of it all. More realistically, relative degrees of historical (like genetic) relationships fall on a continuous scale. The inferential strength of historical analogies—and thus of the DHA itself—will vary accordingly, but there is no good reason why historical analogies cannot be carefully employed to interpret the past, even if there is some historical and cultural distance between the source (e.g., the ethnographic case) and the subject of interest (the archaeological phenomenon). Wylie (1985) has emphasized the importance of bolstering the source-side evidence as much as possible in order to support the inferential strength of an analogy of this type.

Developing source-side support is not solely limited to augmenting continuities over time between ancestral and descendant groups, a fact which has important implications for defining a corpus of directly relevant ethnography. It can also involve cultural equivalencies across similar ethnic groups that may not have direct ancestor-descendant relationships (as defined from a Western genetic perspective). Lewis-Williams (1984), for example, has developed evidence for a “pan-San [southern African Bushmen] cognitive system.” This justifies his use of ethnographic data from the Kalahari San, despite their residence in a region without rocks and thus the fact that they do not make rock art themselves, to interpret the southern San pictographs from the Drakensberg mountains. Based on the evidence for this widespread cognitive system, Lewis-Williams effectively expanded the range of directly relevant ethnography from that recorded in the immediate region of the painted shelters into a much larger area, where the ethnographic record is much richer. This is based on careful attention to source-side support, however, not just on general similarities between the two groups.

The third and final kind of analogy is a formal one; that is, an analogy based on formal resemblances between a series of traits. Equivalencies in form are taken to indicate equivalencies in function, origin, or meaning. Formal analogy is a dubious basis for inference, but this does not mean that formal analogies have no value to archaeological research. They can be useful for generating hypotheses, but additional evidence is always necessary to evaluate propositions based on these weak analogies.

At issue here is our understanding of how humans behave and, based on our apprehension of this large topic, how we may reasonably interpret the archaeological record. As Walker (2002) has correctly emphasized, the deeply embedded yet frequent emphasis on practical reasoning as the basis for human action reflects an inferential bias that ignores common attributes of human social life. Midgley (2003) suggests that the analytical obsession with modeling human behavior as economically rational is an outgrowth of dubious nineteenth-century Spencerian economics. While we may never all agree on the theoretical starting point for human behavior, archaeology will be better served if we are explicit about our intellectual presuppositions in this regard. Simply put, traditional archaeology ignored prehistoric religion in part because traditional archaeologists were not religious and did not think religion mattered. Objectively speaking, even a relatively strained application of the DHA provides a firmer inferential foundation than an interpretation founded on this implicit Western antireligious bias.

Context and Association

Archaeological context and association are particularly important for the identification and interpretation of ritual remains, including both iconographic and artifactual kinds of evidence (Renfrew 1994; Bertemes and Biehl 2001). Marcus and Flannery (1994) note that the value of contextual analysis results from the fact that ritual is, by definition, a behavioral act and must be repeated to have any consequential social value, thereby resulting in patterned evidence that can be discovered in the archaeological record (Gheorghui 2001).

This suggestion is straightforward, but implicit Western biases about context and association include the false belief that all cultures always divide their worlds into sacred versus profane spaces, and the common assumption that two artifacts in locational proximity (thereby in association) were necessarily created during the same prehistoric activity, and thus must have the same function. The problem involves using practical reasoning to interpret ritual remains when one of the associated artifacts has an ostensibly clear utilitarian function whereas use of the other is more ambiguous (Walker 2002). To cite one example, the ritual implications of human burials placed in midden deposits below house pit floors, widely acknowledged by Great Basin archaeologists, demonstrate that a specific location could be used alternately for mundane and ceremonial purposes. Yet at least once a decade an archaeologist will “discover” that a petroglyph panel is adjacent to a bedrock grinding slick and, from this association, proclaim that the art was made as part of plant gathering subsistence activities, even though the ethnography tells us otherwise. This is no more logical than concluding that a human burial placed in a midden is evidence for cannibalism, because of its proximity to dietary remains in the trash deposit; or alternatively that all of the artifacts within the midden were used ceremonially, because of the presence of the burial.

As context and association alone are insufficient for identifying or interpreting prehistoric ritual, so too is artifact condition or even artifact nature, as there is ample archaeological evidence for ritual offerings of apparently mundane or inconsequential objects, for the ritual use of broken objects, and for the use of trash dumps and other putatively profane places for ritual offerings (Walker 1995; Whitley et al. 1999; Chapman 2001; Marangou 2001). This, again, is not because religious behavior is irrational and arbitrary. In fact, it can be quite systematic and logical; it just often follows a cultural logic that is different from our own. In North American Puebloan cultural perception, for example, the proper course for all things is a return to the earth. Trash dumps are an important part of this metaphysical process and, for this reason, they represent a kind of sacred space appropriate for ritual offerings (Walker 1995). In far western North America, similarly, the supernatural is conceptualized as the exact opposite of the natural world. Small and seemingly insignificant natural objects (like twigs, rock chips, feathers, and pennies) are considered appropriate offerings at sacred sites, just as broken objects (e.g., “killed” metates) are found as grave offerings. In the supernatural world, these insignificant or broken items will be significant and/or whole (Whitley et al. 1999).

Our understanding of the meaning and significance of context within the prehistoric culture under study is at issue here. In some cases, this is fairly obvious. Specialized religious structures, marked by unique forms of architecture, art and iconography, and ceremonial objects, are identifiable in some cases. Likewise, certain archaeological phenomena are likely religious in nature, and there may be ritual archaeological deposits associated with these remains. In North America, for example, rock art is almost universally acknowledged as sacred/religious in origin, and the associated deposits may enhance our understanding of the rituals involved (Loendorf 1994; Whitley et al. 1999). In such cases, ritual acts are readily identifiable and may be easily interpreted. But sometimes the distinction between sacred and profane activities at a particular location involves differences in time that are not identifiable archaeologically, as suggested by the occasional juxtaposition of petroglyphs and groundstone, or (perhaps) the discovery of a burial pit originally excavated into a trash midden.

The use of context and association in interpreting religious remains cannot simply rely on some kind of putative practical reasoning. Ideally, it should involve an understanding of the cultural logic of the group being studied, though this only pertains to the recent prehistoric past where ethnographic records and the DHA are available to provide this kind of emic (insider’s) view. More typically, no directly relevant data exist to guide analysis. The best recourse, in such circumstances, is a wide-ranging cross-cultural synthesis that provides a model of the range of variation that might be expected in cultures similar to the one being analyzed. Again, we will only understand prehistoric religions when we adequately apprehend traditional non-Western religions, and use our knowledge of them to aid in our understanding of the prehistoric past.

Iconography, Symbolism, and Neuropsychology

Art and iconography—the study of images—have always been important in the archaeology of religion because artistic corpora are rich sources of information about prehistoric cognitive systems of all kinds. Traditionally the domain of art historians, iconographic analysis is increasingly used by archaeologists, especially in Mesoamerica and Andean South America (Schele and Freidel 1990; Freidel et al. 1993). The most prominent writer on the methods of iconographic analysis was Erwin Panofsky (1983), who argued for three levels of art historical analysis. The first of these is the identification of the subject matter of a particular image (e.g., this is a picture of a horse). The second level is iconographic, here meaning the description and classification of images (e.g., this is a thoroughbred horse, not a draft horse, based on its anatomical details). The third level is iconological, where the image is interpreted and its intrinsic meanings or symbolic values identified (e.g., thoroughbred racehorses are owned by the wealthy and socially elite and thus this picture encodes an aspect of a particular socioeconomic structure).

Although many art historians no longer rigidly adhere to these distinctions and terms, Panofsky’s emphasis on the difference between the identification and the meaning of an image is a crucial one for archaeologists (Lewis-Williams 1990), who often ascribe their own single universal meaning to an image or symbol. Not only does such an uncritical literalist reading of images reflect methodological ignorance, then, but it also represents Eurocentric intellectual arrogance in the extreme. A common example involves the interpretation of depictions of game animal species as “obviously” related to hunting and diet; hunting magic interpretations of rock art are one case in point. Using a comparative analysis of Columbia plateau rock art, where ethnographic evidence supports the creation of some art in hunting magic rituals, and the Coso range, where the ethnography denies any such origin, Keyser and Whitley (2006) suggest that the locations of rock art sites, the kinds of associated features and artifacts, and the nature of the iconography itself can be examined in the absence of ethnographic data to determine whether or not a corpus of motifs can be read literally. Whereas plateau art realistically depicts hunters, herds of game, and drive lanes and corrals, the Coso petroglyphs conflate animal and human features into single composite beings. Determining the meaning of an image may be possible, then, even without ethnographic data, through the use of multiple lines of evidence.

The second implication of Panofsky’s approach concerns the construction of iconographic typologies, which can be difficult because they can be so subjective and hence difficult to replicate. One way to make the typology replicable is to construct a typological key (e.g., figure 31.5), which further separates the process of identifying an image from the determination of its meaning.

Panofsky (1983), third, emphasized the importance of the emic viewpoint to adequately determine the meaning of a motif. For him, this was primarily obtained in period-specific literary sources. Panofsky viewed iconographic interpretation as turning on an adequate understanding of these sources, which are obviously not available for the prehistoric archaeologist. Nonetheless, interpretations of meaning must be culturally based; they cannot be founded on implicit Western attitudes about the putative commonsense meaning of images (Price 2002:44–45). This returns us to the problem of middle-range theory for an archaeology of religion, including the need to use DHA, ethnographic analogy, and cross-cultural ethnographic models even in iconographic analysis.

The centrality of iconographic analysis is evident in rock art research, for obvious reasons, where shamanism, first, and neuropsychology, second, have been prominent recent topics (Lewis-Williams 2001). This circumstance stems from the fact that trance (or ASC) is a central component of shamanistic religious systems, where it is taken as a supernatural or mystical experience, and due to the common (though variable) association between hunter-gatherer societies with both rock art and shamanism. Neuropsychology is important in much research on shamanism because human reactions to ASC are universally shared and reasonably well understood, as are their implications for art, imagery, and symbolic metaphor. As Hobson notes,

Figure 31.5. Typological key for the classification of southern Sierra Nevada rock art motifs (after Whitley 1987).

Alterations of the brain-mind obey reliable and specifiable rules. Whether the states are normal delirium, like dreaming, or an abnormal delirium, like alcohol withdrawal, they always have the same formal features and the same kind of cause. The common features of normal and abnormal delirium are disorientation, inattention, impoverished memory, confabulation, visual hallucinations, and abundant emotions. The common cause of normal and abnormal delirium is a sudden shift in the balance of brain chemicals. (1994:62)

Not all ASC are the same, and they can vary from incident to incident even for a single individual. But they all fall within a known range of variation and, in certain cases, this range of variation is partly determined by the means used to induce trance. Neuropsychological analyses for this reason provide potential opportunities for true functional analogies between the present and the past, giving us a middle-range theory for one kind of iconography.

Neuropsychological models are valuable because they can distinguish nonshamanistic artistic traditions and thus religions, and can serve as the starting point for the analysis of any prehistoric iconography.

The nature of a specific artistic tradition, shamanistic or not, is partly conditioned by culture. While shamanistic corpora of art manifest shared structural principles, the degree to which they are expressed varies from culture to culture. Some cultures, like the South American Tukano, highly value the geometric light percepts called entoptic patterns that occur in the first stage of trance (Reichel-Dolmatoff 1978). Other cultures focus on the full-blown iconic hallucinations that occur in a later stage of an ASC. The neuropsychological models used for analysis, derived primarily from clinical and ethnographic research, incorporate this range of variability, but inferential confidence will typically increase with iconographic complexity (Whitley 2005). For example, a corpus that combines geometric motifs corresponding to common entoptic patterns with figurative images that reflect the somatic metaphors of trance (such as flight) may be more surely attributed to shamanism than a corpus consisting solely of a few repeated geometric images (even these too ultimately may be shamanistic in origin). Again, multiple lines of independent evidence are central to all types of archaeological research.

The importance of cognitive neurosciences research to the archaeology of religion, as noted above, is only beginning to be recognized. These studies are products of a rapidly developing interdisciplinary field referred to alternatively as neurotheology (Aquili and Newberg 1999; Joseph 2003) or the cognitive science of religion (Whitehouse 2000). Much more can be expected from this area of research as it matures. What this approach to religion emphasizes—contradicting the long-standing Western scientific attitude about the putative irrationality of religion—is that it is a cross-cultural universal that derives from the evolution of the human mind-brain and its processes. We will understand religious beliefs and behavior when we understand how the mind operates, providing us with another avenue for middle-range research.

Contrary to the commonly held inductive generalization that an archaeology of religion is futile, it can provide substantial new insights into the prehistoric past, as demonstrated by recent rock art research, especially in southern Africa (Lewis-Williams 1981, 2002a; Lewis-Williams and Pearce 2004; Dowson 1992; Garlake 1995), North America (Whitley 2000; Keyser and Klassen 2001; Bostwick 2002; Francis and Loendorf 2002; Boyd 2003; Hays-Gilpin 2004), and Australia (Layton 1992; David 2002; Morwood 2002). Not only has this research generated considerable new information, but in certain cases (such as southern Africa) we arguably have gained a deeper understanding of prehistoric hunter-gatherer symbolism, cognition, and belief than we have concerning other aspects of culture, including subsistence and technology.

This research has primarily been driven by attention to the ethnographic record; that is, by initially building interpretive models that are ethnographically based and then applying them to the archaeological record. When combined with neuropsychology, this approach has resulted in considerable insight into religion in the deep archaeological past, including the European Paleolithic (Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1988; Lewis-Williams 1991, 2002b; Clottes and Lewis-Williams 1998). This further demonstrates that, while attention to ethnography is important to build plausible models useful for the archaeology of religion, this does not constrain us to research at any particular time or to any limited set of prehistoric cultures.

The final point concerns the relationship of prehistoric archaeological research to the indigenous peoples whose ancestors we study. A series of common problems are apparent when this topic is viewed globally, regardless of whether the context is western North America, Australia, southern Africa or elsewhere (see Jordan, chapter 26; McNiven and Russell, chapter 25). The most striking of these involves sacred sites and remains (including burials) which, seemingly everywhere, are major points of contention (see Green, chapter 22). Local archaeological reactions to indigenous claims of ownership and control or demands for repatriation likewise have followed a standard pattern, regardless of continent or region. This starts with a denial of the indigenous claims based on the belief that scientific knowledge always should hold precedence, and often includes questions about the cultural authenticity and thus validity of these claims.

There is no need to debate (again) the merits of the positions held by the indigenous versus the archaeologists; we all know the arguments for both sides. What is important instead is the practical reality of the situation. In the future, the rights of indigenous peoples will be increasingly acknowledged, and these populations are likely to continue to gain measures of political authority and self-control. The ability to conduct primary archaeological research will suffer, at least as long as we oppose indigenous populations over the treatment of sacred sites and remains.

Rather than continue to decry this situation, it is more useful to ask why this circumstance developed. For more than a century, Western archaeologists have largely assumed that religion is irrelevant and treated religious remains as meaningless or without value as scientific data. Indigenous claims to sacred sites and objects appeared intrinsically spurious because the concept of sacredness itself was viewed as irrational. An archaeology of religion that analytically values and emphasizes the relevance of the kinds of contentious remains stands a good chance of bridging the divide that we have allowed to develop. An archaeology of religion in this sense is not just a useful approach that will help us better achieve a truly holistic archaeology; in certain regions it may provide the only means by which primary archaeological research can survive into the future.

1. The obvious exception to this point is biblical archaeology, which has always been directly if not more or less exclusively concerned with religion (Laughlin 2000; Nakhai 2001). Classical archaeology and other kinds of state-level research (e.g., Classic Maya archaeology), with impressive corpora of art and iconography, often exhibit a greater interest in religion than the disciplinary mainstream does. The discussion that follows is primarily oriented toward prehistoric archaeology, especially of smaller-scale societies where interest in religion has been much less direct and the study of it more problematic.

2. Writing in the twenty-first century, I use “traditional” to indicate the scientific-processual archaeology that dominated research approaches during the past half century. Examples of research emphasizing the archaeology of religion include Renfrew (1985, 1994); Adams (1991); Garwood et al. (1991); Aldenderfer (1993); Marcus and Flannery (1994); Brown (1997); Hall (1997); Biehl and Bertemes (2001); Insoll (2001, 2003, 2004); Price (2001a, 2002); Lewis-Williams (2002a); Lewis-Williams and Pearce (2004); Pearson (2002); and Hayden (1987, 2003).

3. The Western intellectual bias against religion is demonstrated in the post-processualist archaeological literature of the 1980s. Although this did much to loosen the economic-subsistence-technology stranglehold on research that had characterized processual archaeology, religion was rarely mentioned directly by post-processualists even though (religious) symbolism and ritual were often the subjects of their analysis. For example, in Ian Hodder’s (1986) influential Reading the Past, there are no index entries for “religion,” whereas there are twenty-five for “ritual” and thirty for “symbolism.” A similar bias is evident in rock art research. Despite the fact that the majority of the world’s rock art is an expression of religious beliefs and practices, it wasn’t until the mid-1990s, when David Lewis-Williams (1995) explicitly made the point that rock art research is a kind of archaeology of religion, that rock art researchers started discussing their data and analyses specifically in terms of the R word.

4. On a historical note it needs be mentioned that Hawkes’s (1954) ladder of inference was proposed prior to a recognition of the need for middle-range theory and the importance of confounding factors like taphonomic processes in the creation of the archaeological record. As we now know, even the reconstruction of prehistoric diet, which Hawkes placed at the base of the ascending ladder of difficulty, can be inferentially quite difficult.

5. The misapplication of Judeo-Christian traits when interpreting prehistoric religions is more common than one might realize. For example, not all religions emphasize the importance of gods (even when they acknowledge the existence of a creator-deity; Boyer 2001), nor is mythology universally ritualized (or even treated prominently; Whitley 2000). Yet interpretation in terms of gods and myths is too often a starting point for archaeological discussion. Carolyn Tate (1999) provides a compelling analysis of aspects of Olmec religion that moves beyond these biases and illustrates how they can be avoided.

6. Peter Nabokov (2002) notes that many contemporary Native American rituals incorporate a historiographic purpose, demonstrating that there has not been a complete, catastrophic break with the past and that rituals (and thus beliefs) are key contributors to this fact. The irony is in the common archaeological belief that these rituals are not (ethnographically) “authentic” because of changes in subsistence, technology, and other aspects of culture. Yet, as Nabokov shows, it is the rituals themselves that carry the historical traditions and thus ensure some degree of continuity with the past.

Adams, E. Charles. 1991. The origin and development of the Pueblo Katsina cult. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Aldenderfer, Mark. 1993. Ritual, hierarchy, and change in foraging societies. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 12: 1–40.

Barrett, John. 1991. Towards an archaeology of ritual. In P. Garwood, P. Jennings, R. Skeates, and J. Toms, eds., Sacred and profane, 1–8. Oxford Committee for Archaeology, Monograph no. 32. Oxford: Oxbow.

Biehl, Peter F., and François Bertemes (eds.). 2001. The archaeology of cult and religion. Archaeolingua 13. Budapest: Archaeolingua Foundation.

Binford, Lewis R. 1962. Archaeology as anthropology. American Antiquity 28: 217–225.

———. 1977. General introduction. In For theory building in archaeology: Essays on faunal remains, aquatic resources, spatial analyses, and systemic modeling, 1–7. New York: Academic.

Bloch, Maurice. 1974. Symbols, song, dance, and features of articulation: Is religion an extreme form of traditional authority? Archives: European Journal of Sociology 15: 55–81.

———. 1986. From blessing to violence: History and ideology in the circumcision ritual of the Merina of Madagascar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 1992. Prey into hunter: The politics of religious experience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Boric, Dussvan, and Sofiya Stefanovic. 2004. Birth and death: Infant burials from Vlasac and Lepenski Vir. Antiquity 78: 526–547.

Bostwick, Todd W. 2002. Landscape of the spirits: Hohokam rock art at South Mountain Park. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Bourget, Steven. 2001. Rituals of sacrifice: Its practice at Huaca de la Luna and its representation in Moche iconography. In J. Pillsbury, ed., Moche art and archaeology, 88–109. Washington, DC: National Art Gallery.

Boyd, Carolyn E. 2003. Rock art of the lower Pecos. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

Boyer, Pascal. 2001. Religion explained: The evolutionary origins of religious thought. New York: Basic.

Bradley, Richard. 1998. The significance of monuments: On the shaping of human experience in Neolithic and Bronze Age Europe. London: Routledge.

———. 2000. An archaeology of natural places. London: Routledge.

Brown, Ian W. 1989. The calumet ceremony in the Southeast and its archaeological manifestations. American Antiquity 54: 311–331.

Brown, James A. 1997. The archaeology of ancient religion in the Eastern Woodlands. Annual Review of Anthropology 26: 465–485.

Carr, Christopher. 1995. Mortuary practices: Their social, philosophical, religious, circumstantial, and physical determinants. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 2: 105–200.

Chapman, John. 2001. Object fragmentation in the Neolithic and Copper Age of southeast Europe. In P. F. Biehl and F. Bertemes, eds., The archaeology of cult and religion, 89–110. Archaeolingua 13. Budapest: Archaeolingua Foundation.

Clottes, Jean, and J. David Lewis-Williams. 1998. The shamans of prehistory: Trance and magic in the painted caves. New York: Abrams.

Conway, Thor, and Julie Conway. 1990. Spirits on stone: The Agawa pictographs. Heritage Discoveries Publication no. 1. San Luis Obispo, CA.

Cowgill, George L. 1993. Distinguished lecture in archeology: Beyond criticizing new archeology. American Anthropologist 95: 551–573.

Crystal, Eric. 1974. Man and the Menhir: Contemporary megalithic practice of the Sa’Dan Toraja of Sulawesi, Indonesia. In C. B. Donnan and C. W. Clewlow Jr., eds., Ethnoarchaeology, 117–128. Los Angeles: UCLA Institute of Archaeology.

Damasio, Antonio R. 1994. Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. New York: Putnam.

D’Aquili, Eugene, and Andrew B. Newberg. 1999. The mystical mind: Probing the biology of religious experience. Minneapolis: Fortress.

David, Bruno. 2002. Landscapes, rock art, and the dreaming: An archaeology of preunderstanding. London: Leicester University Press.

Dowson, Thomas A. 1992. Rock engravings of Southern Africa. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press.

Durkheim, Emile. [1912] 1965. The elementary forms of religious life. Trans. J. W. Swain. New York: Free Press.

Elkin, A. P. 1977. Aboriginal men of high degree. 2nd ed. New York: St. Martin’s.

Flannery, Kent V., and Joyce Marcus. 1993. Cognitive archaeology. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 3: 260–270.

Fogelin, Lars. 2005. The archaeology of early Buddhist ritual. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira.

Francis, Julie E., and Lawrence L. Loendorf. 2002. Ancient visions: Petroglyphs and pictographs from the Wind River and Bighorn country: Wyoming and Montana. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

Freidel, David, Linda Schele, and Joy Parker. 1993. Maya cosmos: Three thousand years on the shaman’s path. New York: William Morrow.

Garlake, Peter. 1995. The hunter’s vision: The prehistoric art of Zimbabwe. London: British Museum Press.

Garwood, Paul, P. Jennings, Robin Skeates, and Judith Toms (eds.). 1991. Sacred and profane. Oxford: Oxbow.

Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The interpretation of cultures. New York: Basic.

Gheorghui, Dragos. 2001. The cult of ancestors in the eastern European Chalcolithic: A holographic approach. In P. F. Biehl and F. Bertemes, eds., The archaeology of cult and religion, 73–88. Archaeolingua 13. Budapest: Archaeolingua Foundation.

Guenther, Matthias. 1999. From totemism to shamanism: Hunter-gatherer contributions to world mythology and spirituality. In R. B. Lee and R. Daly, eds., The Cambridge Encyclopedia of hunters and gatherers, 426–433. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gumerman, George. 1994. Corn for the dead: The significance of Zea mays in Moche burial offerings. In S. Johannessen and C. A. Hastorf, eds., Corn and culture in the New World, 399–410. Boulder: Westview.

Hall, Robert L. 1997. An archaeology of the soul: North American Indian belief and ritual. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Hampton, O. W. “Bud.” 1999. Culture of stone: Sacred and profane uses of stone among the Dani. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

Hastorf, Christine A. 2003. Andean luxury foods: Special foods for the ancestors, deities, and elites. Antiquity 77: 545–555.

Hawkes, Christopher. 1954. Archaeological theory and method: Some suggestions from the Old World. American Anthropologist 56: 155–168.

Hayden, Brian. 1987. Alliances and ritual ecstasy: Human responses to resource stress. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 26: 81–91.

———. 2003. Shamans, sorcerers, and saints: A prehistory of religion. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Hays-Gilpin, Kelley Ann. 2004. Ambiguous images: Gender and rock art. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira.

Higgs, Eric S., and G. Jarman. 1975. Paleoeconomy. In E. S. Higgs and G. Jarman, eds., Paleoeconomy, 1–7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hill, James N. 1994. Prehistoric cognition and the science of archaeology. In C. Renfrew and E. Z. B. Zubrow, eds., The ancient mind: Elements of cognitive archaeology, 83–92. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hobson, J. Allan. 1994. The chemistry of conscious states: Toward a unified model of the brain and the mind. Boston: Little, Brown.

Hodder, Ian. 1986. Reading the past: Current approaches to interpretation in archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Horton, Robin. 1976. African traditional thought and Western science. Africa 37(1–2): 50–71, 155–187.

———. 1982. Tradition and modernity revisited. In M. Hollis and S. Lukes, eds., Rationality and Relativism, 201–260. Cambridge: MIT Press.

———. 1993. Patterns of thought in Africa and the West: Essays on magic, religion, and science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Huffman, Thomas N. 1986. Cognitive studies of the Iron Age in Africa. World Archaeology 18: 84–95.

———. 1996. Snakes and crocodiles: Power and symbolism in ancient Zimbabwe. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press.

Insoll, Timothy. 2003. The archaeology of Islam in sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 2004. Archaeology, ritual, and religion. London: Routledge.

Insoll, Timothy (ed.). 2001. Archaeology and world religion. London: Routledge.

Jelinek, Jan. 1990. Human sacrifice and rituals in Bronze and Iron Ages: The state of the art. Anthropologie 28: 121–128.

Jemison, G. Peter. 1997. Who owns the past? In N. Swidler, K. E. Dongoske, R. Anyon, and A. S. Downer, eds., Native Americans and archaeologists: Stepping stones to common ground, 57–63. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira.

Jordan, Peter. 1999. The materiality of shamanism as a “world-view”: Praxis, artifacts, and landscape. In N. Price, ed., The archaeology of shamanism, 87–104. London: Routledge.

———. 2003. Material culture and sacred landscape: The anthropology of the Siberian Khanty. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira.

Joseph, Rhawn (ed.). 2003. NeuroTheology: Brain, science, spirituality, religious experience. San Jose, CA: University Press.

Keyser, James D. 2004. The art of the warrior: Rock art of the American plains. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

Keyser, James D., and Michael A. Klassen. 2001. Plains Indian rock art. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Keyser, James D., and David S. Whitley. 2006. Sympathetic magic in western North American rock art. American Antiquity 71: 3–26.

Kirch, Patrick V. 2004. Temple sites in Kahikinui, Maui, Hawai’ian Islands: Their orientation decoded. Antiquity 78: 102–115.

Kroeber, Alfred L. 1925. Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 78. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Kunen, Julie L., Mary Jo Galindo, and Erin Chase. 2002. Pits and bones: Identifying Maya ritual behavior in the archaeological record. Ancient Mesoamerica 13: 197–211.