Power over South Asia: The ‘Seven Cities’ of Delhi and the Saptusindhu Capital Region

Like China, south Asia has had many capitals in its long history, but few of these have actually controlled the whole of its vast territory. The most enduring of Indian capitals, and the one which, with a single notable exception, has been the centre of power over the largest part of the subcontinent, is Delhi. This has been the dominant capital of the subcontinent throughout much – but by no means all – of its modern history.

As a capital Delhi goes back further than Beijing, but in reality it has over this long period been not so much a single city as a cluster of cities occupying contiguous sites. Delhi, asserted Percival Spear, ‘has undergone transformations as numerous as the incarnations of the God Vishnu’. Yet, ‘it has preserved through all a continuous thread of existence’.1 According to legend there have been seven cities of Delhi, but Spear was of the opinion that there have in reality been as many as double that number. Stretching around this cluster of cities is the territory known as the Saptusindhu, the principal core region of India.2 The Saptusindhu, Hindi for ‘seven rivers’, stretches from the Punjab, the land drained by the five main eastern tributaries of the Indus, to the Doab, the area stretching between the middle courses of the Ganga and its major tributary, the Yamuna. This has been overwhelmingly the most powerful geopolitical focus of power in the whole of south Asia.

As with the other great imperial cities, there are many legends concerning the origins of Delhi. An interesting one comes from the Mahabharata, the epic poem which has its origins in the time of, or before, the Aryan invasions of India. It has been suggested by scholars that Indraprastha, the capital city of the Pandavas, was in fact the first Delhi. The likelihood that this is true is, according to Spear, ‘a circumstantial probability’. The oldest evidence of a city on the site are the ruins at Purana Kila in the heart of modern Delhi, dated by pottery to the tenth century BC. Just to the north was another legendary site, that of Kurukshetra, the great battlefield between the Pandavas and the Kauravas in the Mahabharata. Thus the Delhi region has from the outset been linked to legendary political and military power. This is something which has over the years considerably strengthened its hold on the Indian imagination and added legitimacy to its position as capital.

As with all capitals, there are also powerful geopolitical factors accounting for the importance of Delhi through the centuries. One of these suggests that there is some basis for the Mahabharata legend since very close to the city is the historical battlefield of Panipat, the site of a number of important battles in Indian history. Most of these have been between the forces of the indigenous Hindu population and invaders from the north. It is on the great plain north of Delhi that the confrontation between the two has most frequently taken place. Since the earliest times, Delhi has been the location where successful invaders have set up their centre of power. It lies strategically at the centre of the Saptusindhu, and is well connected to most other routes. As a result, it is the place from where invaders have been best able to assert their control over the rest of the subcontinent. Besides these powerful geographical advantages, the Delhi region is also central to the whole of the madhyadesa, the huge plain stretching from the Indus valley to the Ganga-Brahmaputra valley, the territory with the largest population and the greatest agricultural and industrial potential. This is the area which, above all others, invaders have sought to conquer. The city is also situated close to the watershed between the two major rivers in northern India, the Ganga and the Indus. This has given it control over routeways to the west and east and also to the south between the Aravalli hills of Rajasthan and the escarpments of the northern Deccan. This strategic location is reinforced by the fact that Delhi is where the Aravallis finally dip beneath the alluvium of the Indo-Gangetic plain. At this point it forms the Ridge, a long series of hills on the northeastern side of the city. Yet despite these formidable geographical advantages, Delhi was not actually the first city chosen to be the capital of an Indian imperial state.

The first unification of India, the Mauryan Empire in the third century BC, chose Pataliputra, now Patna, in the middle Ganga basin, to be its capital. This is located well to the east of the Doab. The successor Gupta Empire in the third century AD inherited the same capital. Outside the legends, Delhi does not actually appear as a leading centre of power until the twelfth century and this related to the arrival of powerful invaders from the north. These were the Turks from Central Asia who, following their conversion to Islam, used their new religion as a justification for expansion and conquest. They arrived through the mountains of Afghanistan using the natural routes, notably the Khyber Pass, which led down into the Indus valley. The first such invasion was that of Mahmud of Ghazni in 997, who for a time was able to occupy much of the upper Indus region. This was followed in 1191 by another invasion from Afghanistan by Muhammad of Ghur. His army was met by the army of a Hindu confederacy led by the Rajput prince Prithviraj at Tarain, close to the legendary battlefield of Kurukshetra. At the second of the two battles on this site the invaders were successful in defeating Prithviraj in 1192, moving on from there to capture Delhi. This had been one of the strongholds of Prithviraj, one of whose titles had been ‘Lord of Delhi’. The city is thought by some to have been his capital but there is no positive proof of this.

Whatever the truth of this, the invaders chose Delhi as their capital and there established the Delhi Sultanate, which was to be the major power in the subcontinent for the next 300 years. During this period there were a number of dynasties and until the last of them the Delhi area remained the site of the capital and principal seat of power.

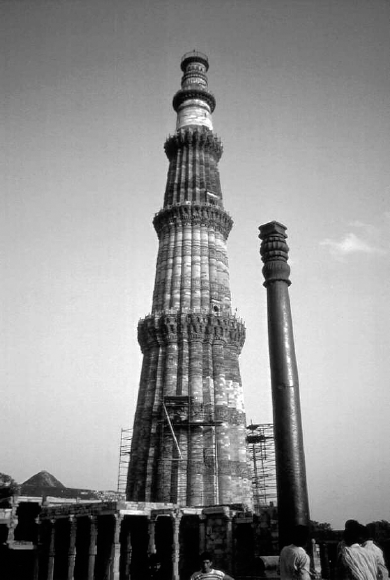

The Sultanate actually came into being in 1206, the first sultan being Qutb-ud-Din Aibak. Qutb had been a slave of Muhammad of Ghur but when Muhammad returned to Afghanistan he seized power himself. It was his immediate successor Iltutmish who really established the dynasty and was responsible for the first buildings of the Sultanate in Delhi. The place chosen for these was Lal Cot, which had been the site of Prithviraj’s city about 5 km from the first Delhi at Purana Kila. There Iltutmish first built a great victory tower, the Qutb Minar, named after the founder of the dynasty, which proclaimed the triumph and supremacy both of the dynasty and of Islam. It was modelled on the great tower of Ghazni in Afghanistan where the first projected conquest of India had originated in the tenth century. This immense structure towered over the surrounding countryside and was clearly intended as an unmistakable assertion of the new dominant power in India. It was certainly an uncompromising demonstration of power in stone, which was exactly what the Sultanate wished to achieve. In the fourteenth century Ibn Batuta, who for a time lived in Delhi, described it thus:

(The Minar) has no parallel in the lands of Islam. It is built of red stone … ornamented with sculptures and is of great height. The ball at the top is of glistening white marble and its ‘apples’ [small balls surmounting a minaret] are of pure gold. The passage is so wide that elephants could go up it.3

The Qutb Minar, Delhi. Constructed around 1200, this minar was a powerful symbol of the arrival of Islam in India.

At the same time the building of the Quwwat-al-Islam mosque was begun nearby. In this immense structure the humiliation of the Hindus was made even more evident by the use of stones from existing Hindu temples which had been destroyed. The remains of these Hindu sculptures are still to be seen in the mosque’s stonework. The great citadel built at Lal Cot was the centre of the dynasty’s power and became the principal residence of the sultan. By the end of the Slave dynasty the size of this capital city had grown considerably but its principal purpose was clearly to be an overwhelming demonstration of the new power dominating the land. The centre of power of the Sultanate always remained, said Spear, not so much a capital as ‘the headquarters of an army of occupation’.4

The Slave dynasty was followed by the Khilji, the most important sultan of which was Ala-ud-Din Kilji. This sultan, who styled himself the ‘second Alexander’, is historically significant for a number of reasons, in particular the fact that he resisted and defeated the attempt by the Mongols to extend their domains into India. He continued to embellish the impressive Qutb site with varying results. The great mosque of the Quwwat was further enlarged but the most ambitious of all his projects was the attempt to construct another victory column close to the Minar which was intended to be even larger. In fact it was on a truly immense scale and its projected height would have dwarfed the Qutb Minar itself. However, he did not complete this huge structure in his lifetime and all attempts to continue with it after his death met with complete failure. Ibn Batuta was, however, clearly impressed even by the ruin:

This minar is one of the wonders of the world for size, and the width of its passage is such that three elephants could mount it abreast. The third of it built equals in height the whole of the other minaret … though to one looking at it from below it does not seem so high because of its bulk.5

Only the base of this gigantic tower actually remains today. It proved beyond the capacity of the architects of the time and it stands today as a kind of Ozymandian reminder of the fragility of power.

Close to the Qutb Minar is yet another great column made of pure iron. For a long time this was thought to have been intended as another demonstration of the power of the Sultanate, this time using metal. However, analysis has now shown it to date from the Gupta period and to have come from the Pataliputra area in the heart of the Gupta Empire. It must have been brought to its present site and erected there as a suitable addition to the Qutb site. It would certainly have been used as another symbol to complement the Minar and, in particular, yet another demonstration of the Sultanate’s domination over the native Hindus.

The remains of the gigantic minar built by Ala-ud-Din Kilji. Intended originally to surpass the height of the nearby Qutb, it was never fully completed and soon collapsed.

Ala-ud-Din also built an imperial palace at Siri some 3 km to the northeast of the Qutb site. This lavish building came to be known as the ‘Hall of a Thousand Pillars’ and was the place where the sultan preferred to live and to conduct much of the business of state.

In 1320, after only thirty years, the Khiljis were replaced by a third dynasty. These were the Tughluqs, the most important sultan of which was Muhammad bin Tughluq. His reign has been referred to as the golden age of the Sultanate during which the lands controlled by Delhi were at their most extensive. During this period northern India had a stable government and for a long time enjoyed relative prosperity. However, it was during the reign of his predecessor and founder of the dynasty, Ghiyas ud Din Tughluq, that the third Delhi of the Sultanate was built. This was Tughluqabad, built on a defensive site using a rock outcrop. The Tughluqs were a severe military dynasty and this is reflected in the nature of their seat of power. Built like a fortress and surrounded by formidable stone walls, at its centre was a massive citadel. It was redolent of military strength and what has been called ‘the stark cyclopean grandeur of Tughluqabad’ reflected all aspects of their austere regime.6 Muhammad bin Tughluq did not much favour this enormous and grim fortress city and for a time even transferred the capital south to Daulatabad in the Deccan, where he was engaged in military operations. However, he soon returned to Delhi which the sultans had always seen as being the best and most effective centre for the government of their domains.

Following their defeat of the Arabs and the Ottoman Turks, the Mongols by the fourteenth century had achieved a position of dominance over Eurasia. As a result of this, Muhammad now considered the Sultanate to have become the real centre of Islam and the Islam in which he believed was in tune with the dynasty’s overall characteristics. Everything they built was in an uncompromising, grim style and this included their religious buildings. Muhammad’s main contribution to the Tughluq building operations was at Jahanpannah between Qutb and Siri where he built a new palace and mosque, both in the unmistakable Tughluq style. The Tughluqs were aiming above all to present a statement of power and this they achieved most effectively. Muhammad was now a leader of considerable importance in the Muslim world and he was visited in Tughluqabad by emissaries from as far afield as Baghdad. The records show that these emissaries were impressed by the stark grandeur of the Tughluq capital and by the distinctive and puritanical picture of Islam it conveyed.

Muhammad was succeeded by his nephew Firoz who, as well as continuing with the embellishment of the existing buildings of Delhi, built his own fortress-palace at Firozabad close to the Yamuna river about 10 km to the north. In so doing, he transferred his capital to a completely fresh site which has been described as a kind of ‘New Delhi’ of the fourteenth century.7 Here the sultan built a magnificent royal palace, the Ferozshah Kotla, which he seems to have used particularly for grand receptions and ceremonies of state in preference to either Tughluqabad or Qutb. It was also the place where this particular sultan preferred to make his residence. This seems to have impressed one British traveller who went so far as to refer to it as being the ‘Windsor’ of Delhi.8

Nevertheless, despite all these changes, both Tughlaqabad, as a grim and uncompromising statement of power, and Qutb, as a triumphal symbol of victory, remained the two most potent symbols of the power of the Sultanate. Qutb itself seems to have been regarded as the official capital and it certainly remained the most impressive and enduring symbol of their power throughout the period of the Sultanate.

In 1398, ten years after the death of Firoz, Timur Lenk – Tamerlane – invaded India and, as in so many other places, the results were rapid and catastrophic for much of the north of the country. Delhi was plundered and sacked and the sultan was humiliated and reduced to being a vassal of the great Central Asian conqueror. The Tughluq Sultanate never fully recovered from this and the last of the dynasty died in 1414. The Sultanate continued in name only under the Sayyid dynasty which at times ruled little more than Delhi itself and remained, nominally at least, vassals of Timur’s successors.

In 1451 power was seized by the Lodis, warlords from the Punjab, who left little more than their tombs in Delhi as memorials to their rule. The first of the Lodis, Buhlul Khan, re-established the power of the Sultanate and this was continued by his son, interestingly – and inappropriately – named Sikander (Alexander). Initially, Sikander made Qutb his capital and built there another new mosque, the Moti Masjid, the only major addition to the architecture of Delhi during the whole period of this dynasty. So Qutb, the first great symbol of the new power in India two and a half centuries earlier, continued to retain its hold and became the principal symbol of the power of the revived Sultanate in the middle of the fifteenth century. However, Delhi’s role as capital was to be brief and the stern heavy tombs of the Lodis remain the most telling memorials to their rule. Sikander came increasingly to see Delhi as being far too vulnerable to new attacks from the north. As a result he forsook what had been the centre of the power of the Sultanate since its inception, with its dramatic symbols of former glory, and embarked on the building of a new capital further east in the Doab. This was Sikanderbad, close to Agra, and the sultan moved there around 1500. From there he judged the Sultanate could exert control over the rich Ganga-Brahmaputra plain and would be safer from attacks by the northern tribes. In the final stages of its existence, the Sultanate was edging its centre of power closer to the old Hindu capital of Pataliputra. Nevertheless, some of the mystique of Delhi must have remained because Sikander’s tomb is in the old capital.

However, the Sultanate was not made any safer by this move. Afghanistan remained a turbulent centre of expansionist activity and this related to the events taking place in the lands of the Timurid dynasty. In 1526 the Sultanate was forced to do battle with the next invaders on the fateful field of Panipat, north of Delhi. These were the Mughals, also Turks from Central Asia, and they defeated the army of the sultan and rapidly occupied northern India. The new rulers decided to keep the capital near to Sikanderbad, establishing themselves in Agra, about 10 km further east. Their leader was Babur, a product of the great Timurid civilization of Central Asia. He was said to be the most brilliant Asiatic prince of his age and claimed descent from both the Mongol Genghis Khan and the Turkish-Mongol Timur. Like the Sultanate, the Mughals were also Muslim and so were able to fit easily as successors to the Lodis. Their religion still separated them from the great majority of their new subjects, in particular the large population of the Ganga-Brahmaputra plain together with the whole of the Deccan. As had happened before, a large Hindu force was assembled, led again by the Rajputs, which sought to defeat these new invaders. However, like the forces of Prithviraj, they were defeated and the Mughals were able to consolidate their regime.

Successful as they were in battle, the military prowess of the Mughals was by no means truly representative of the nature of this new dynasty. They were certainly far from being another version of the warlike Tughluqs. The early Mughals at least proved civilized rulers who introduced a great tradition of art and architecture which they brought with them from their Timurid homeland. They spoke Persian and had been considerably influenced by Persian art, architecture and literature. As a result, during the centuries of their rule, they left an indelible mark on the culture of India. Babur, himself a highly cultivated man, had a poor opinion of the people of his new domains. India’s great attraction was ‘an abundance of gold and silver’ and the fact that ‘workmen of every profession and trade are innumerable and without end’.9 In other words, India’s main virtue was that it could be exploited easily and was a good base for the creation of an empire. This is what the Mughals then proceeded to do, in the course of which they bequeathed to India some of its most stunning and memorable architecture.

Babur’s son Humayun, bookish and intellectual, was attracted back to Delhi where he engaged in considerable building near the old Purana Kila site. However, he proved a weak and ineffectual ruler and his reign was a turbulent one which endangered the continuation of the new dynasty. For a time he was removed from the throne but he was eventually reinstated. Babur had loved his Afghan homeland and on his death in 1530 his body was taken back to Kabul for burial. Humayun was the first Mughal emperor to be buried in India and his splendid tomb in Delhi is an early and magnificent example of Mughal architecture. His son Akbar was a complete contrast to his father and his reign was the most important in the whole of Mughal history. It was he who secured the dynasty’s full control over its Indian possessions.

THE FIRST SIX GREAT MUGHALS

Babur 1526–30

Humayun 1530–56*

Akbar 1556–1605

Jahangir 1605–27

Shah Jahan 1627–58

Aurangzeb 1658–1707

*Humayun was faced with many rebellions during his reign and for a time he was forced into exile. The most important of the rebels was Sher Shah who himself ruled from 1540 to 1545.

Akbar proved a resolute and effective ruler, introducing many measures to improve governance. His domains were divided for administrative purposes into provinces, each of which had a governor. The coinage was reformed and new silver coins were minted. The taxation system was also reformed and made fairer to the peasantry. Most importantly, an attempt was made to break down the great gulf between Muslims and Hindus and to integrate the whole of the population more effectively. Hindus were introduced into the higher levels of the administration and often even reached the level of provincial governors. An important symbolic gesture was that a Hindu was appointed to be the governor of Afghanistan, the home province of the empire and always dear to the hearts of the Mughals. This all helped produce greater stability and so promoted trade and general prosperity.

Akbar decided that he needed a strong fortress in Agra, making use of the easily worked local red sandstone as a building material. When completed in 1570 this massive building was a powerful statement of Mughal power and, apart from the fact that it was in red stone, it was hardly less uncompromising and forbidding than Tughluqabad. However, the Mughals were in most ways very different from the Tughluqs and, while the fort may have displayed their power, it gave little indication of the great civilization they brought to India. They were after all Timurids, and this division between power and civilization was in many ways a duality similar to that found in the buildings of Timur himself.

In 1570 Akbar embarked on the building of a new capital which he clearly intended to be the principal symbol of his own reign and policies. This capital was Fatehpur Sikri, the ‘City of Victory’, located some 40 km to the south of Agra. It may have been a city which celebrated Mughal victories, but its origins lay in much more personal matters. The story is that Akbar had no son to continue the dynasty and this greatly concerned him. One day he stopped to rest at the village of Sikri where he was told of a holy man, a hermit, who lived in a cave nearby. This was Salim Chisti who was believed to possess miraculous powers. Akbar visited the holy man and revealed his plight to him. Salim suggested that Akbar’s wife, Maryam-uz-Zamani, daughter of a Hindu prince, should come to reside at Sikri for a time and this she did. Within a year she had given birth to a son, the future emperor Jahanghir. Akbar was overwhelmed with joy and, as an act of thanksgiving, announced that the capital was being transferred to Sikri where a great city would be built. Work began immediately and by 1574 the citadel was complete and Akbar and his court moved into it. No sooner had the Agra fort been completed than it was abandoned for this new city.

While the legend is very telling, there were, of course, other factors involved in this choice of site. It was located on the route from the Doab to the south, following the river Chambal deep into the Deccan, and the Gulf of Cambay. This gave the capital ready access to the west of the country with its important sea communications. The region was also blessed with a ready supply of fine red sandstone which became the basic building material for the city as it had for Agra. It had the added advantage of being very close to Agra. Of course, the policies adopted by Akbar were designed to have the effect of pacifying his domains but the presence of the great fortress nearby must have been reassuring.

The Panch Mahal, Fatehpur Sikri.

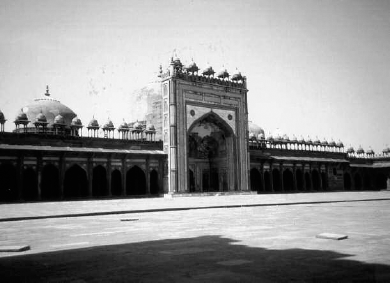

The Jama Masjid Mosque, Fatehpur Sikri.

The city which rose in the desert to the south of Agra was indeed magnificent. It was surrounded by walls and had seven gates leading in all directions. One of the highest and most striking buildings was the Panch Mahal, the five-storeyed palace, used by Akbar and his court for rest and pleasure. Its architectural style showed considerable Hindu influence, something which is to be found in many of the other buildings throughout the city. Architecture was another aspect of the attempt by Akbar to create a fusion of Muslims and Hindus and put his empire on firmer foundations.

By far the largest and grandest building in Fatehpur Sikri was the Jama Masjid mosque. At the time it was also the largest mosque in India and was built on the plan of the great mosque at Mecca. Again its architecture represents a blend of the Mughal and Hindu styles. Akbar was himself a deeply religious man and initially his whole regime was closely associated with Islam. After all, religion, and particularly his veneration of the holy man, was at the heart of the whole project. In 1579 Akbar proclaimed himself imam, making himself head of the whole Muslim religious community of his empire. The inscription in Persian above the entrance to the mosque makes it clear that it was Akbar who was responsible for its building and adornment, which ‘is second only to the chaste mosque’ (in Mecca). The mosque complex is built in a large courtyard surrounded by cloistered walls. There are two great gateways, one leading into the city itself and the other facing outwards to the south.

Near to the mosque was the tomb of Salim Chisti, who had died around 1576. This is generally acknowledged to be one of the finest examples of a Mughal building. It is in white marble, and has been called a pearl set in a ring of sandstone. The mausoleum at its centre is faced in pure white marble and the tomb itself has a canopy of wood inlaid with mother-of-pearl. The existence of this magnificent tomb in the centre of the city shows clearly the importance given to religion at the heart of the activities of the empire.

Akbar’s cultivation of the Hindu princes related to his eclectic religious policy which was formulated over a period of years in Fatehpur Sikri. In 1578 the emperor organized a series of debates in which he participated. At first they were confined to Muslims but were later extended to include Hindus, Parsees (Indian Zoroastrians), Buddhists, Jains and, eventually, Christians. These latter were in the first instance Portuguese missionaries. The debates took place in the Diwan-i-Khas, the hall of private audience which came now to be used as the Abadat Khana, ‘the Hall of Worship’. The participants sat in small kiosks around the walls facing one another. In the debates, free speech was encouraged and the emperor listened carefully to the often highly divergent opinions being expressed. As a result of these debates Akbar began to cast a critical eye on Islam and in 1579 the ‘Infallibility Decree’ was promulgated. This was what officially made the emperor imam and the head of Islam in India. As imam, he took on the twin role of pope and emperor and decided what was and what was not acceptable Islamic practice.

Out of this ferment of activity the emperor then evolved the idea of a new eclectic religion which would contain the best elements from all the religions. This was the ‘Din Allahi’, the Divine Faith, established in 1582. Its exact contents remain a mystery but it appears to have centred on Akbar himself as its prophet. It postulated ‘suh-i kul’, tolerance of all religions, but paradoxically Islam itself came to be treated with increasing harshness.

Despite all the work and expenditure on his new capital city, the emperor did not actually remain there for very long. After fifteen years he abandoned the city and moved back to Agra. The reasons for this decision are still shrouded in mystery: one theory has been that the water supply in this dry area proved insufficient for the growing population. However, recent scholars have suggested that there were probably other reasons. Agra was on the great line of communication stretching from the northwestern frontier to the delta of the Ganga. This was the main axis of northern India, and so a capital located on it was better placed for the exercise of control over northern India. Later this came to be known as the ‘Grand Trunk Road’, made famous by Rudyard Kipling in Kim. In addition, as he became older Akbar became more conscious of security, particularly in view of the highly controversial policies he was pursuing. The fort at Agra was a formidable stronghold and far more secure than the relatively open city of Fatehpur, which did not have very high protective walls. While Fatehpur was built for a land at peace, Agra was built for a land in which peace was not so certain. For a time Akbar also moved to Lahore in the Punjab, which was a good base for dealing with northern frontier problems and for maintaining the links with Afghanistan which remained strong. It was not, however, the best location for his later campaigns in southern India and for these Fatehpur was occasionally used again.

This may explain why towards the end of his reign Akbar built his last great addition to Fatehpur Sikri, the Buland Darwaza, the ‘Gate of Victory’. This triumphal gateway to the Jama Masjid mosque was added in 1601 to commemorate victories in southern India. The style once more blends the Mughal and Hindu and the inscription above the entrance reads ‘Jesus, son of Mary, said, on whom be peace: the world is a bridge, pass over it but build no house upon it.’ The image of the bridge, which can be found elsewhere in Fatehpur, encapsulated the idea of a link between the divergent peoples and religions of the empire which Akbar was striving for. It is a remarkable inscription to be found on a mosque.

The Buland Darwaza was built on a low hill with 40 steps leading up to it. In this way it towered impressively over the city and the surrounding countryside. It was described by the architectural historian James Fergusson as being ‘noble beyond any portal attached to any mosque in India, perhaps in the whole world’.10 Although leading to a mosque, this final addition to the architecture of Fatehpur Sikri is far more an expression of power than anything else in the city. While by this time engaged in many other projects, including the religious ones, the emperor still commanded his armies in the field and was conscious of being master of a great empire.

Akbar’s final years were spent mostly in the fort at Agra, his first building project. It was a far more secure stronghold than any building in Fatehpur. There he died in 1605 and his son and successor Jahangir, the child born in Sikri, built his magnificent tomb nearby at Sikanderabad.

Jahangir did not return to Fatehpur but remained in the safety of the fort at Agra. An indolent emperor given more to the pursuit of pleasure than to governing the empire, he largely continued the policies of his illustrious father and, while he went back to Islam, the policy of religious toleration was maintained. Jesuits and members of other faiths were welcomed at his court, as were ambassadors from neighbouring countries and Europe. It is interesting to note that during the reign of Jahangir the first English trading settlements were established in India and later in the century the merchant Job Charnock founded Calcutta (Kolkata). This was eventually to become the main base for the power which two centuries later would replace the Mughals. Sir Thomas Roe was designated to be England’s first ambassador to the court of the Great Mughal. His reception was a far friendlier one than that given a century and a half later by the Chinese emperor to Lord Macartney. The two great oriental empires behaved very differently towards the arrival of the Europeans and the events that unfolded during the following centuries reflected this difference.

Jahangir’s son and successor, Shah Jahan, proved far more energetic and generally aggressive in his policies. The policy of religious toleration was revoked and Christian churches, including the one in Agra, were razed to the ground, as were a number of Hindu temples. For the first decade of his reign he remained in Agra and it was there that his beloved young wife Mumtaz Mahal died in 1631. Distraught at this calamity, he immediately threw himself into the great project of building a magnificent tomb for her. This was the Taj Mahal which for a number of years became his main preoccupation. It took an enormous amount of effort and was a considerable strain on the coffers of the state.

In 1638 Shah Jahan made the momentous decision to move the capital back to Delhi. It may have been that Agra, filled with memories, had become a sad place for him but he would also have seen the strategic superiority of Delhi as a location for the control of India. Agra had, after all, been chosen as a place of refuge by the beleaguered Sultanate, but expansion rather than defence was on the mind of the new emperor. Agra and Fatehpur were also indelibly associated with Akbar, and Shah Jahan certainly did not wish to remain in the shadow of his illustrious grandfather. Although the earlier Great Mughals had rarely used Delhi, it did have a special place for them since it had been the historic symbol of the triumph of Islam on the subcontinent. The place which Shah Jahan chose for his new city was close to the Yamuna river and about 15 km north of the Qutb site. Here between 1639 and 1648 the new city of Shahjahanabad rose on the low-lying land adjacent to the Yamuna. When completed the city was large and impressive. It had massive walls with 27 towers and eleven gates. Its population by the end of Shah Jahan’s reign has been estimated as being around 400,000.

The city was planned on a grid pattern with a grand processional way, the Chandni Chowk, at its centre. Its most impressive and important feature was the Red Fort, the imperial residence and centre of government. This was modelled on the fort at Agra and, like the latter, overlooked the Yamuna river. From then on the emperor, himself a natural builder, spent the greater part of his time and effort on it. He had a special love for marble which he had used lavishly in the building of the Taj Mahal. Together with the red sandstone which gave the fort its name, this was the main building material, but many other precious and semi-precious stones and jewels were also used, usually inlaid into the stonework.

The basic purpose of the Red Fort was to be an impressive centre of government and to symbolize power in stone. That this purpose was achieved there can be little doubt. The comments of the English traveller Lovat Fraser make this quite clear:

There is one place in Delhi, the first sight of which is unforgettable. It is enshrined behind the titanic rose-pink walls of the vast Fort, those huge masses that look as though they were built for all time. The great battlements tower above you as you enter a formidable gateway … and stand in the centre of a gigantic hall with vaulted roof. It is like the nave of a cathedral. Beyond it you enter an open space that is called a courtyard … You cross it, advance through another mighty archway and confront the Diwan-i-Am.11

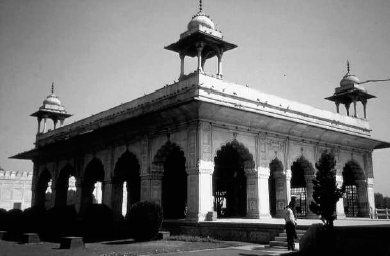

The Diwan-i-Am, the hall of public audience, was one of its two most important buildings. It was the pivot of the whole Red Fort. The impressive approach is, as Fraser said, through two great archways and a courtyard. The Diwan was an open pavilion supported by arches. It was built on a low platform at the centre of which was the imperial throne. It was here that the emperor dealt with matters of state in a public way in front of his subjects. According to Nicholson, it was ‘the Mughal Empire’s centre stage for displaying its greatest pomp and ceremony’.12 The whole pavilion was painted in bright colours and behind the throne was a panel with brightly coloured pictures of flowers and birds. Above this was a painting of the Greek god Orpheus playing his lyre. Since this was taken from a painting by Raphael on the same subject it strongly suggests that Italian artists and craftsmen had been hired for the building and decoration of the most important building in the fort.

The Diwan-i-Am was the splendid sight seen by those who entered the fort through the ceremonial arches and were witness to the display of the magnificence and power of the emperor. Coming from outside, one reached the Diwan by means of the great processional route of the Chandni Chowk and the Lahore Gate and the whole was clearly intended to constitute a complete experience. However, the real centre of the power of the Empire, where policies were discussed and decisions made, was not there but well behind it and hidden from public view. This was the Diwan-i-Khas, the private audience hall, where the really important business of the Mughal Empire was conducted. It was here that the emperor met with his ministers and others summoned to the palace to discuss the most important and secret matters. This Diwan was even more magnificent than the other. It was built of marble and inlaid with precious stones. As with the Diwan-i-Am, much use was made of colour and the walls were bedecked with paintings boasting an abundance of leaves and flowers. On a marble dais at the centre was the pièce de résistance of the whole Diwan, the Peacock Throne which Shah Jahan had had made for himself. It was inlaid with a variety of precious stones and seemingly no cost had been spared in its making. The Frenchman François Bernier was certainly impressed and has left a detailed description of one particular ceremonial which he witnessed there:

The King appeared seated upon his throne, at the end of the great hall, in the most magnificent attire. His vest was of white and delicately flowered satin, with a silk and gold embroidery of the finest texture. The turban of gold cloth had an aigrette whose base was composed of diamonds of an extraordinary size and value, besides an Oriental topaz, which may be pronounced unparalleled, exhibiting a lustre like the sun. A necklace of immense pearls suspended from his neck … The throne was supported by six massy feet, said to be of solid gold, sprinkled over with rubies, emeralds and diamonds. I cannot tell you with accuracy the number or value of this vast collection of precious stones, because no person may approach sufficiently near to reckon them … But I can assure you that there is a confusion of diamonds, as well as other jewels … It was constructed by Chah-Jehan, the father of Aureng-Zebe, for the purpose of displaying the immense quantity of precious stones accumulated successively in the treasury from the spoils of ancient Rajas and Patans, and the annual presents to the monarch, which every omrah is bound to make on certain festivals.13

The Diwan-i-Am, Red Fort, Delhi. The centre of power of the Mughal Empire and place where the Great Mughals gave audiences to their subjects and to representatives of foreign powers.

When Bernier returned to France this information was passed to Louis XIV who was himself involved in a similar project to demonstrate his power. The French monarch was no doubt curious to know how an oriental despot managed such things.

Visitors would certainly have been dazzled by the magnificence of the whole vast new centre of Mughal power. The intention to overawe was heightened by the elaborate ceremonial associated with the approach to the emperor. At every stage it was made abundantly clear that this was the ultimate source of unbridled power. However, for those in the sovereign’s entourage who lived within the great walls this was a place of exquisite beauty which possessed everything to make life pleasant. On the central wall of the Diwan was inscribed the couplet by Khusrau in Persian,

If on earth there be a paradise of bliss,

It is this, Oh! It is this! It is this!

The many other buildings of the fort included the harem and the private quarters of the emperor. All were set off by the splendour of the large open spaces and the Mughal gardens which certainly would have given the idea that this was paradise.

The Mughals derived a great deal of their culture from the Persians and this was displayed in this ultimate centre of their power. But it was only incidentally a paradise and its real purpose was to make clear to all where the absolute power in the empire lay.

As always with the Mughals, and before them the Sultanate, there was the explicit acknowledgement that their power was not entirely of their own making but derived from and sanctioned by Islam. The other most impressive building of Shahjahanabad was the Jama Masjid mosque. When completed, it was designated as the royal mosque of the Empire, used by the emperor and his court for worship. It was built, like the fort, in red sandstone and inlaid with marble and brass. Three great marbled domes and two tall minarets dominate its skyline. On the east side the open arcading of the mosque faces towards the Red Fort and this emphasizes the strong relationship between these two dominating buildings. The mosque was built on a low hill, the highest part of the city, and so in order to enter it one had to ascend by a series of flights of steps. These led to a grand entrance arch much like the Buland Darwaza in Fatehpur. This was the entrance used by the emperor when he and his entourage arrived for Friday Prayers. The imperial procession would leave the fort by the Delhi Gate and proceed from there the short distance to the mosque. The imperial party then climbed the steps and went in through the grand entrance. Besides prayer, this was also intended as another demonstration of the close links between Islam and the state in the Mughal Empire.

In this ‘New Delhi’ of Shah Jahan the rituals of empire were conducted with great regularity and punctiliousness. Unlike Akbar’s capital, here there was no debate or discussion, no openness to new ideas or willingness to make changes. There was just an immense certainty about the greatness and the rightness of the Mughal Empire and its domination over India. As one historian put it, ‘The outspoken animation of Akbar’s symposia had given way to a more awesome ceremonial and a more exalted symbolism. Now the “King of the World” ethereally presided from sun-drenched verandas of the whitest marble.’14 It has been observed that, when sitting on his Peacock throne, the backdrop was designed to look as though there was a glowing halo around Shah Jahan’s head in the saintly Christian manner.

Barely twenty years after the foundation of Shajahanabad it became clear that the grip of Shah Jahan was weakening. This produced a war of succession among his sons. One of them, Aurangzeb, was in command of the army of the Deccan which was aiming to bring the restive south of India more firmly into the Mughal grasp. In 1657 he moved back northwards to secure his succession to the throne. He defeated his brothers and imprisoned his father in the fort at Agra. From there the old emperor was able to look out towards the Taj Mahal, his most loved and beautiful creation, and to wait for his own death and entombment alongside his beloved Mumtaz Mahal.

Aurangzeb was a strict puritan and as emperor he enforced Islam in his domains with an iron will. In terms of building projects he was the complete opposite of his father. While Shah Jahan had been a great and enthusiastic builder, Aurangzeb was given more to destruction. He ravaged the north of India, destroying Hindu temples and monuments and leaving a trail of bitterness and hatred behind him. He was the complete opposite of Akbar who had attempted to bring together his diverse peoples and in whose architectural legacy this can be seen. Aurangzeb, on the other hand, left virtually no architectural legacy. When he was in Delhi he resided at the Red Fort and was careful to observe the rituals devised by his father. His one addition to the fort was the Delhi Gate which was rebuilt in an austere style. It was intended to match the great entrance gate of the mosque and to form an impressive backdrop for the imperial processions.

With the aggressive policy of Aurangzeb continuing undiminished, the banner of Hindu resistance to Islam, and to northern power, was taken up by the Marathas. They and their allies put up such a determined resistance to Mughal rule that in 1681 Aurangzeb moved south with his army and remained there for most his life. He established there a new capital, Aurangabad, which became his base. More a military camp than a city, it was abandoned soon after his death. By 1691 Mughal power, secured exclusively by military means, was at its height and almost the whole of the Indian subcontinent was in their hands. This had been achieved with great brutality and Aurangzeb was himself responsible for the most appalling atrocities. All this increased the implacable hostility of the Hindu population of both south and north. The huge campaigns drained the resources of the treasury in much the same way that the building projects of his father had, but with far less of a legacy.

Aurangzeb died in 1707 while on campaign in the south. He had attempted to put the whole of India into a straitjacket of his own making but in the end it all proved a complete failure. By the time of his death the empire had never been bigger but it was so weakened that it never fully recovered. His successors attempted to make peace with the Hindus of the south and to undo some of his excesses but with little success. Very soon after his death the empire began to show signs of disintegration.

In 1739 the king of Persia, Nadir Shah, invaded the now weak empire. He saw the increasing turmoil in India as his chance to add to his power and wealth. He came via the well-trodden route from Afghanistan and his forces confronted and defeated the army of the Mughals on the historic battlefield of Panipat. On reaching Delhi his troops engaged in the usual bout of destruction and looting. The loot taken by the king himself included the fabulous Peacock Throne, the most important symbol of Mughal power. This was taken back to Persia where it became the symbol of the Persian dynasty and its removal marked the end of the effective power of the Mughals. The emperors were from then on little more than shadows, pawns in the hands of adventurers. As Spear put it, ‘The Great Moghuls of the seventeenth century degenerated into embarrassed phantoms in the eighteenth century.’15 Finally, in 1804 the emperor Shah Alam put himself under the protection of the British. The fledgling maritime power which had established a tentative base in Calcutta during the reign of Jehangir had by the nineteenth century become the dominant power in India. The emperor received the British commander, Lord Lake, in the Diwan-i-Khas simply dressed and under a tattered canopy. The Peacock Throne was long gone and the old blind emperor was seated humbly on the ground. To the British he presented a pathetic sight. It was all so very different from the great audiences of Shah Jahan in the same Diwan 150 years earlier. Shah Alam’s lack of any real power was expressed in the Persian couplet:

From Delhi to Palam,

Is the realm of Shah Alam.16

The great Mughal Empire did not so much fall as fade away, and a new power was poised to take over. This power was eventually to leave its own legacy among the ‘seven cities’ of Delhi.