Much has been written of the medieval ambivalence that simultaneously placed woman on a pedestal and reviled her as the incarnation of evil. Preachers tirelessly repeated the tale of Eve’s beguiling Adam, while elevating the Virgin Mary to the status of a cult. Correspondingly, in the lay world, woman was extolled by the troubadours, the trouvères and the Minnesingers, and debased in the bawdy fabliaux.

Clerical misogyny was as old as the Church. Not only orthodox Christians, but Stoics and Gnostics reacted against the materialistic and libertine life of the Roman upper class by adopting negative attitudes toward women and sex. Their asceticism fitted Christian eschatology, the conviction that Christ’s second coming was at hand. “The time is short,” warned Saint Paul.1 “The world is full,” wrote Tertullian a century later, adding, in language that prefigures that of modern advocates of zero population growth, “The elements scarcely suffice us. Our needs press…. Pestilence, famine, wars and the swallowing of cities are intended, indeed, as remedies, as prunings against the growth of the human race. “2 Those who appeared on the Day of Judgment with “the excess baggage of children” would be handicapped. As for those who justified marriage by “concern for posterity and for the bitter joy of children,” such a consideration was “hateful” to Christians.3 To Paul’s preference for celibacy (“I would that all men were as I myself,”4 “It is good for a man not to touch a woman”5), and demand for feminine submission (“Wives, submit yourselves unto your husbands, as unto the Lord”6), Tertullian added invective:

And do you not know that you are Eve? … You are the gate of the devil, the traitor of the tree, the first deserter of Divine Law; you are she who enticed the one whom the devil dare not approach; you broke so easily the image of God, man; on account of the death you deserved, even the Son of God had to die.7

Yet even this ferocious misogynist must be taken with a grain of sugar; Tertullian, like many early churchmen, was married and referred to his wife as “my beloved companion in the Lord’s service.”8

Anti-feminine diatribes similar to those of the Church Fathers can easily be gleaned from clerical writings of the Middle Ages. A modern writer quotes this from Marbode, an eleventh-century bishop of Rennes: “Of the numberless snares that the crafty enemy [the devil] spreads for us… the worst… is woman, sad stem, evil root, vicious fount … honey and poison.”9 The same writer quotes Salimbene, author of a thirteenth-century chronicle: “Woman, glittering mud, stinking rose, sweet venom … a weapon of the devil, expulsion from Paradise, mother of guilt….”10

Yet such expressions, cited to show the Church’s bias, are misleading. Marbode’s lines are drawn from a section of his Liber Decern Capitulorum (Book of Ten Chapters) specificallytitled De Meretrice (On the Prostitute). In the same poetic work, under the title De Matrona (On the Matron), he speaks in another tone entirely: “Of all the things that God has given for human use, nothing is more beautiful or better than the good woman.” He cites the roles of comforter, mother, cook, housewife, spinner, and weaver, declares that the worst woman who ever lived does not compare with Judas and the best man does not equal Mary, and names an honor roll of women from the Old Testament and the early Christian saints.

Salimbene was a Franciscan friar, presumably writing for an audience of fellow monks. Like many political bodies before and since, the medieval Church tailored its ideological expressions to suit its varying constituencies. Monks who had taken the vow of chastity found themselves locked in a lifelong struggle to stick to it, and needed all the encouragement they could get. For general audiences, however, the tone might be critical but was pitched on a different plane. Affluent women were chided for their extravagance of dress, whims of fashion, cosmetics, and frivolity. Gilles d’Orléans, a Paris preacher of the thirteenth century, reminded his parishioners that the wigs they wore were likely to be made from the hair of persons now enduring hell or purgatory, and that “Jesus Christ and his blessed mother, of royal blood though they were, never thought of wearing” the belts of silk, gold, and silver fashionable among wealthy women.11

Still different was the note sounded when the audience was composed exclusively of women. Ad omnes mulieres (To All Women), a text extensively used by medieval preachers, was drafted by the thirteenth-century Dominican Master-General Humbert de Romans:

Note that God gave women many prerogatives, not only over other living things, but even over man himself, and this (i) by nature; (ii) by grace; and (iii) by glory.

A thirteenth-century representation of the expulsion from Eden, for which Eve’s frivolity was blamed. British Library, MS Stowe 17, f. 29.

(i) In the world of nature she excelled man by her origin, for man He made of the vile earth, but woman He made in Paradise. Man he formed of the slime, but woman of man’s rib. She was not made of a lower limb of man—as for example of his foot—lest man should esteem her his servant, but from his midmost part, that he should hold her to be his fellow, as Adam himself said: “The woman whom Thou gavest as my helpmate.”

(ii) In the world of grace she excelled man…. We do not read of any man trying to prevent the Passion of Our Lord, but we do read of a woman who tried—namely, Pilate’s wife, who sought to dissuade her husband from so great a crime…. Again, at His Resurrection, it was to a woman He first appeared—namely, to Mary Magdalen.

(iii) In the world of glory, for the king in that country is no mere man but a mere woman is its queen. It is not a mere man who is set above the angels and all the rest of the heavenly court, but a mere woman is; nor is anyone who is merely man as powerful there as is a mere woman. Thus is woman’s nature in Our Lady raised above man’s in worth, and dignity, and power; and this should lead women to love God and to hate evil.12

Even Tertullian mended his language when addressing an audience of women, scolding them for using makeup but calling them “handmaids of the living God, my companions and my sisters.”13

At the two extremes of its rhetorical needs the Church found two perfect symbols: shallow temptress Eve and immaculate Virgin Mary. The perception of women by medieval churchmen differed little from that of laymen: women were properly subject to men because they were physically and morally vulnerable, and lacking in judgment. Yet they were personalities, separate from their husbands (a more liberal view than Blackstone’s in the eighteenth century), with their own souls, their own rights and obligations. Marriage was good, a sacrament instituted by Christ, and woman was created to be man’s helpmate, “included in nature’s intention as directed to the work of generation,”14 in the words of Aquinas, although man was “the beginning and end of woman; as God is the beginning and end of every creature.”15

In the secular world the knightly troubadour described his lady in a tone at once romantic and gently ironic, as “worth more than all the good women in the world,”16 beautiful, accomplished, with “fair speech and gentle manner… her sweet look… sends a burning spark to my heart”;17 his love was “a greater folly than the foolish child who cries for the beautiful star he sees high and bright above him”;18 he “loves and serves and adores her with constancy.”19 Along with these elevatednotions went admonitions for courteous treatment: “Serve and honor all women,” recommended the thirteenth-century Roman de la Rose. “Spare no pain and effort in their service.”20

The authors of the earthy and popular fabliaux, on the other hand, depicted peasants’ or burghers’ wives as irrepressibly adulterous, lustful, and treacherous, tirelessly deceiving their husbands with priests, students, and apprentices, and nearly always getting away with it.

In the same satiric tradition was the anonymous Quinze Joyes de Manage (Fifteen Joys of Marriage—the title taken sacrilegiously from a prayer enumerating the fifteen joys of the Virgin Mary’s life). The theme was the battle of the sexes, and the protagonist was a respectable burgher whose ill-tempered wife squandered his money, withheld her sexual favors, and made his life miserable out of sheer perversity. Pregnant (“and perhaps not by her husband, which often happens”), she develops a capricious appetite and yearns for new and strange things, sending her poor husband in search of them night and day, on foot or on horseback. After the child is born, she makes him take her on an expensive pilgrimage while she complains endlessly of the pains she suffered—though they were not more than those of “a hen or goose that lays an egg as big as a fist through an opening where before a little finger could not have passed…. Thus you will see that, by laying every day, a hen will keep fatter than a cock; for the cock is so stupid that he does nothing all day long but search for food to put in her beak, and the hen has no care but to eat and cackle and take her ease.” Meanwhile the husband may not be “as lively as before… but she is just as lively as ever…. And when the lady is not satisfied with her husband’s attentions… she thinks that her husband is not so potent as others…. And sometimes some women set out to discover whether other men are as lacking as their husbands.”

In fact, the wife in the story deceives her husband with a succession of gallants. When he catches her in bed with one, her mother, friends, and even confessor conspire to make him doubt the evidence of his own eyes. Worsted in every encounter, he occasionally beats her, but the last word is always hers. Each “joy” concludes, “Thus will he spend his life in suffering and torment and end his days in misery.”21

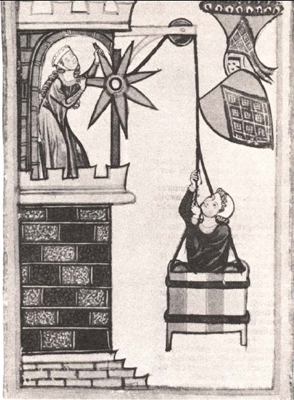

Lady hoists her lover to her window by winch and pulley, in illustration from a fourteenth-century collection of poems of German Minnesingers. Heidelberger Universitätsbibliothek, Manesse Codex, f. 71v.

Lovers. “Serve and honor all women” was the typical adjuration of chivalric poetry. Heidelberger Universitätsbibliothek, Manesse Codex, f. 249.

The inconsistency of the two literary traditions is as superficial as that found in the sermons. Both troubadour and writer of fabliaux dealt with the same theme, adultery, the one romantically, the other satirically. The ladies of the troubadour verses are married to “cruel, jealous husbands,”22 and the love is specifically sexual. In the twelfth century, the Countess of Dia, one of twenty known woman troubadours, wrote:

I should like to hold my knight

Naked in my arms at eve,

That he might be in ecstasy

As I cushioned his head against my breast,

For I am happier far with him

Than Floris with Blancheflor;

I grant him my heart, my love,

My mind, my eyes, my life.

Fair friend, charming and good,

When shall I hold you in my power?

And lie beside you for an hour

And amorous kisses give to you;

Know that I would give almost anything

To have you in my husband’s place,

But only if you swear

To do everything I desire.23

Only the attitude and the social class are different. Medieval literature was neither the first nor the last to treat adultery as romantic for the upper classes and comic for the lower.

The troubadours’ sympathy for illicit love was rationalized in the twelfth-century treatise De Amore (On Love) by Andreas Capellanus (André the Chaplain), based on Ovid. According to De Amore, love could not exist “between two people who are married to each other,” but only “outside the bonds of wedlock.”24

Whether De Amore was intended literally or satirically, a point still debated, its ideology, like that of the troubadours, is in unmistakable conflict with medieval living realities which stoutly upheld the ancient double standard in respect to adultery. Kings, barons, knights, and burghers openly kept mistresses and spawned illegitimate children, while erring wives were disgraced and repudiated, their lovers castrated or killed. In a wife’s adultery the affront was perceived not to morality but to the husband’s honor. Spanish law in the thirteenth century provided that a husband or fiancé could kill the woman and her lover and “pay no fine for the homicide, nor be sentenced to death,”25 while in some fourteenth-century Italian cities adulterous women were flogged through the streets and exiled.26

Despite such pieties as the Roman de la Rose’s “Serve and honor all women,” wife-beating was common. “A good woman and a bad one equally require the stick!” ran a Florentine saying.27 The thirteenth-century French law code, Customs of Beauvais, stated: “In a number of cases men may be excused for the injuries they inflict on their wives, nor should the law intervene. Provided he neither kills nor maims her, it is legal for a man to beat his wife when she wrongs him.”28 An English code of the following century permitted a husband “lawful and reasonable correction.”29 And a fifteenth-century Sienese Rules of Marriage advised husbands:

When you see your wife commit an offense, don’t rush at her with insults and violent blows: rather, first correct the wrong lovingly and pleasantly, and sweetly teach her not to do it again…. But if your wife is of a servile disposition and has a crude and shifty spirit, so that pleasant words have no effect, scold her sharply, bully, and terrify her. And if this still doesn’t work … take up a stick and beat her soundly … not in rage, but out of charity and concern for her soul….30

Lover invites his lady to go for a walk in the woods. Heidelberger Universitätsbibliothek, Manesse Codex, f. 395r.

A contemporary English handbook, however, warned young men that beating their wives would cause resentment because

Though she be servant in degree,

In some degree she fellow is.31

If courtly literature did not in its content accurately mirror the life of aristocratic women, its very existence as an artistic form reflected something about their emerging role. The product of the growing affluence of the high Middle Ages, it expressed the sophisticated aspirations of a new leisure class. Women dominated the audience for this new-wave literature. Even in the male-biased context of feudalism, the germ of future court and salon life was discernible. During the battle of Mansourah, one of the Crusading barons remarked to Saint Louis’s biographer, Jean de Joinville, “By God’s bonnet, we shall talk of this day yet, you and I, in the ladies’ chamber.”32 The battle would be discussed and evaluated in a social gathering presided over by women, even as in eighteenth-century Paris or twentieth-century Washington.

The intellectual spirit of the high Middle Ages contributed in another way to the perception of woman’s role and character. Science still remained in the dark about the mother’s part in conception. Male semen was visible and tangible, and its relationship to reproduction readily deducible, but the discovery of the female ovum awaited the invention of the microscope.

In its absence, medieval thinkers pursued the conjectures of classical writers in explaining the fact, evident in animals as well as humans, that offspring inherited traits from both parents. Aristotle, the universally honored authority, thought menstrual fluid had something to do with the mystery, but even to Aristotle the uncertain nature of the woman’s contribution made it seem of secondary importance. The man, he concluded, produced the “active principle” in conception, the life or soul, the essential generative agency; the woman contributed “matter.”

Wife-beating was common in the Middle Ages, but a misericord (choir stall decoration) in Westminster Abbey shows a reversal of custom. Victimized husband is holding a distaff, normally a female symbol. National Monuments Record.

Some of Aristotle’s contemporaries (said Aristotle) thought

that the female contributes semen during coition because women sometimes derive pleasure from it comparable to that of the male and also produce a fluid secretion. This fluid, however, is not seminal; … the female, in fact, is female on account of an inability of sort, viz., it lacks the power to concoct semen…. The male provides the form …, the female provides the body…. Compare the coagulation of milk. Here, the milk is the body, and the fig juice or the rennet contains the principle which causes it to set…. We see that the thing is formed from them only in the sense in which a bedstead is formed from the carpenter and the wood, or a ball from the wax and the form.33

Further, Aristotle declared that women were “weaker and colder by nature, and we should look upon the female state as being as it were a deformity, though one which occurs in the ordinary course of nature.”34 Following these ideas, Thomas Aquinas pronounced that “woman is defective and misbegotten.” The active force in the male seed produced a “perfect likeness” in the form of a male child; when a female child was produced, it was because of “a defect in the active force.”35

Interpreting and amending Aristotle, the German scholar Albertus Magnus, teacher of Thomas Aquinas at the University of Paris, propounded a view of woman’s sexuality which, to say the least, runs counter to many latter-day notions of medieval beliefs. Albertus demonstrated to his own logical satisfaction that women experienced greater desire and greater pleasure than men. Contrary to Aristotle’s assertion, he believed that women as well as men emitted seed in orgasm, and since women both emitted and received, their pleasure was double. Albertus thought the menstruum was female seed that collected in the womb between menstrual periods and increased desire until menstruation provided relief. From this he concluded that man’s pleasure might be more intensive, but woman’s was more extensive. During pregnancy, when the menstruum was retained to form and nourish the fetus, a woman attained the peak of desire. Albertus’s scholarly proof that women enjoyed sex more than men had its basis, nevertheless, in the notion of malesuperiority: woman, an imperfect being, desired conjunction with man, a perfect being, since the imperfect desires to be perfected; therefore the greater desire and pleasure belonged to the woman.

Scientifically speaking, Albertus found sex beneficial and necessary for women, who often became ill when they were “full of spoiled and poisonous menstrual blood. It would therefore be good for such women … to have frequent sexual intercourse so as to expel this matter. It is particularly good for young women, as they are full of moisture…. Young women, when they are full of such matter, feel a strong desire for sex….”

The sage concluded, “It is therefore a sin in nature to keep them from it and stop them from having sex with the man they favor, although [their doing so] is a sin according to accepted morality. But this is another question.”36

A physiological concept much closer to reality than those of Aristotle, Aquinas, or Albertus Magnus already existed in the theory of Aristotle’s brilliant successor, Galen, whose second-century A.D. medical works were not conveyed to medieval Europe (via the Arabs) till the fourteenth century. Galen foreshadowed William Harvey’s seventeenth-century discovery of the ovum by expressing the conviction that women had internal “testicles” located on either side of the uterus “and reaching down as far as its horns,” smaller than male testicles but containing seed “just as men’s do.”37

The psychological significance of Galen’s theory was apparent in its reception by Western writers who feared that it would enhance feminine pride. “Woman is a most arrogant and extremely intractable animal,” wrote a sixteenth-century Italian physician, “and she would be worse if she came to realize that she is no less perfect and no less fit to wear breeches than man…. To check woman’s continual desire to dominate, nature arranged things so that every time she thinks of her supposed lack she may be humbled and shamed.”38 A Spanish contemporary added that Galen’s notion should be kept secret from women lest they become “all the more arrogant by knowing that they … not only suffer the pain of having to nourish the child within their bodies… but also that they too put something of their own into it.”39

In the absence of Galen, a passive and secondary role in procreation might be attributed to women, but in no one’s eyes did it rule out a feminine interest in sex. Quite apart from Albertus Magnus, the chastity of women was eternally suspect in the eyes of the canonists (clerical lawyers), who perceived them as ever eager for sexual gratification. The thirteenth-century Italian canonist Henry of Susa, known as Cardinal Hostiensis, told the story of a priest who made a journey with two girls, one riding ahead of him, the other behind; at the end of the trip he was prepared to swear to the virtue only of the girl in front.40

Saint Paul’s recommendation, “Let the husband render to his wife what is due her, and likewise the wife to her husband,”41 was unanimously interpreted by medieval theologians as making intercourse mandatory at the request of one spouse or the other. Wives sighed for satisfaction, declared Cardinal Hostiensis, and husbands were morally and legally obliged to honor the demand. Otherwise the weak, readily stimulated creatures were led into adultery, which some ignorant women did not even realize was a sin.

Chaucer’s Wife of Bath commended “the proverb written down and set/In books: ‘A man must yield his wife her debt,’“ and inquired merrily, “What means of paying her can he invent/Unless he use his silly instrument?”42 The seriousness with which the Church regarded the marital debt is shown by the comment of ascetic Guibert, twelfth-century abbot of Nogent-sous-Coucy, about Sybille, wife of the Count of

Namur, a woman of many lovers and intrigues: “Would she have kept herself in check if [the Count] had paid her the marriage debt as often as she desired?”43

Guibert’s own mother might have served as an example to him that not all women were sex-hungry. A noblewoman, beautiful, intelligent, and commanding, she was given “when hardly of marriageable age” to a knight, but her frigid piety induced in the young husband an impotence that lasted several years—a situation that their relatives blamed on “the bewitchments of… a stepmother.” The young man’s family first urged divorce, then tried to persuade him to become a monk—not for the good of his soul, “but with the purpose of getting possession of his property.” When these measures were ineffective, they pressed the girl to leave her husband, and rich neighbors tried to seduce her. The spell was not broken until the husband, at the suggestion of “evil counselors,” had intercourse with another woman and she conceived a child. After that, Guibert recorded, “my mother submitted to the duties of a wife as faithfully as she had [formerly] kept her virginity…. “44

Officially the Church maintained that marital intercourse was permissible only for the purpose of procreation. The sin involved in sex for pleasure was not, however, a large one, as long as procreation was not prevented. Saint Augustine held that it could be atoned for by everyday acts of Christian charity, like almsgiving, and observed that the sin was not uncommon: “Never in friendly conversations have I heard anyone who is or who has been married say that he never had intercourse with his wife except when hoping for conception.”45 Mortal sin, Augustine thought, could only be involved if one was “intemperate in his lust.”46

Thirteenth-century canonist Bishop Huguccio recognized that coitus, for whatever purpose, was unavoidably accompanied by “a certain itching and a certain pleasure … a certainexcitement,” and therefore characterized it as a sin, but “a very small venial sin.”47 Other theologians divided the act of sex into stages and asserted that it could be initiated for a good purpose (in addition to procreation, “good purposes” were the avoidance of fornication and payment of the marital debt) but might reach a point at which one became “submerged in the delight of the flesh,”48 constituting a venial sin. Others drew an even finer distinction, between “enjoying” and “suffering pleasure.”49

Like later institutions burdened with the guardianship of sexual morality, the medieval Church felt called on to judge the question of position in intercourse, its ideas coinciding with those of popular morality then and long after: the only “fitting way” was with the woman supine beneath the man. The “normal” position was regarded as natural and appropriate not only because it seemed to symbolize man’s superiority to woman, but because it was credited with favoring conception and thus fulfilling the procreative purpose. All deviations were not only sins, but mortal sins. Throughout the early Middle Ages monks who heard confession exacted a carefully graded system of penances for nonprescribed positions: so many days of fasting for intercourse with the woman on top, so many for oral, so many for anal intercourse, so many for contraception, either coitus interruptus or contraceptive potions.

The manuals for confessors that began to appear in the late twelfth century were cautious about explicitly naming the sexual sins, lest the confessor inadvertently put ideas into parishioners’ heads. One manual instructed him to begin, “Dearly beloved, perhaps all the things you have done do not now come to mind, and so I will question you.” Then he was to interrogate the subject in terms of the seven deadly sins without asking any specific questions about sex, “for we have heard of both men and women by the express naming of crimes unknown to them falling into sins they had not known.”50 Athirteenth-century book advised the confessor to explain, “You have sinned against nature when you have known a woman other than as nature demands,” but not to reveal the different ways; instead he was to say, “You know well the way which is natural,” and to continue with tactful and generalized questioning.51

Apparently husbands often resented the priests’ interrogating their wives. Fifteenth-century preacher Bernardine of Siena reported, “Often a fool woman, that she may appear respectable, will say to her husband, ‘The priest asked me about this dirty thing and wanted to know what I do with you,’ and the fool husband will be scandalized with the priest.” Confessors who had experienced the anger of husbands tended to be gingerly in their questioning. Bernardine urged them to do their duty and inquire.52

Contraception was condemned by the Church, sometimes as homicide, sometimes as interference with nature, sometimes as a denial of the purpose of marital intercourse. The early fifteenth-century French preacher Jean Gerson condemned “indecencies and inventions of sinners” in marriage: “May a person in any case copulate and prevent the fruits of marriage? I say that this is often a sin which deserves the fire. To answer shortly, every way which impedes offspring in the union of man and wife is indecent and must be reproved.”53 Bernardine of Siena was even more emphatic: “Listen: each time you come together in a way where you cannot generate, each time is a mortal sin…. Each time that you have joined yourselves in a way that you cannot give birth and generate children, there has always been sin. How big a sin? Oh, a very great sin! Oh, a very great sort of sin!”54

How far the Church’s injunctions about the procreative purpose of intercourse were followed is conjectural. Very pious persons seem to have attempted to obey them. Marguerite of Provence, consort of Louis IX of France (Saint Louis), told her confessor, William of Saint Pathus, that the king often avoided looking at her, explaining that a man should not look on that which he could not possess. To impress the reader of his Life of St. Louis with the king’s saintliness, William wrote that he did not consummate the marriage until he had spent three nights praying, and that he remained continent during Advent and Lent, on Thursdays and Saturdays, on the eves of great festivals, and on the festivals themselves, and finally on the days before and after he received communion.55

Similarly we are told that when Hedwig, wife of the Duke of Silesia, found she was pregnant, she “avoided her husband’s proximity, and firmly denied herself all intercourse until the time of her confinement.” Hedwig maintained this scrupulous pattern through the births of three sons and three daughters, after which, apparently with her husband’s agreement, she “altogether embraced a life of chastity.” She was rewarded with sainthood.56

Ordinary people doubtless committed many sexual sins, both venial and mortal. The acts for which the monks demanded penances must have been common, or they would not have been listed in the manuals. Like all epochs, the Middle Ages had to come to terms with human sexuality, and in so doing invented very little and discarded very little.

As from time immemorial, prostitution flourished. By the high Middle Ages it was widely regulated by law, especially in the cities and at markets and fairs, which offered serving girls, tradeswomen, and peasants’ daughters an opportunity to earn extra cash. In many places distinctive dress—hoods or armbands—was prescribed, or prostitutes were forbidden to wear jewelry or certain finery. Some towns, like Bristol, banned prostitutes along with lepers from inside the city walls; more, like London, confined them to certain streets. In Paris, wherethey are said to have formed their own guild, with Mary Magdalene as patron saint, they were especially numerous in the Latin Quarter, where their brothels commingled with the scattered classrooms and residences of the University, and scholarly disputations on the upper floor competed with arguments among harlots, pimps, and customers below. Famous Paris preacher Jacques de Vitry complained that the girls solicited clergymen on the street and derisively cried, “Sodomite!” after those who hastened past.57

Like all established authority, the Church disapproved of prostitution in principle and tolerated it in practice, even protecting the prostitute’s right to collect her fee. The prostitute was seen as behaving in accordance with weak female character; consequently heavier penalties were imposed on customers, pimps, and brothelkeepers. Prostitutes were essentially regarded as beneath the law’s contempt, a condition inherited from Roman times. They could not inherit property, make legal accusations, or answer charges in person, but they were left unmolested in practicing their profession.

The Middle Ages brought one rather spectacular advance, when eleventh-century Byzantine emperor Michael IV built in Constantinople “an edifice of enormous size and very great beauty” (according to chronicler Michael Psellus). The emperor issued a proclamation that prostitutes might there adopt nuns’ habits “and all fear of poverty would be banished from their lives forever…. Thereupon a great swarm of prostitutes descended upon this refuge … and changed both their garments and their manner of life.”58 Michael’s example was imitated in the West, from the twelfth century on. In 1227 Pope Gregory IX gave his blessing to the Order of Saint Mary Magdalene, which established convents in several cities. The nuns wore white and were known as the “White Ladies.” Louis IX, after a vain effort to abolish prostitution, endowed similar establishments.

An alternative for prostitutes who wished to reform was marriage. The early Church discouraged such marriages, but the twelfth-century canonist Gratian decreed that while a man might not marry a whore who continued her trade, he could marry her to reform her.

That medieval women in their varied social circumstances resented and resisted male misogyny is suggested by Chaucer’s independent-spirited Wife of Bath, whose fifth husband amused himself in the evening by reading to her from the “book of wicked wives.” First he read her of Eve

whose wickedness

Brought all mankind to sorrow and distress,

Root-cause why Jesus Christ Himself was slain

And gave His blood to buy us back again.

Next he read her about Samson and his betrayal by Delilah; then of Hercules and Deianira—”She tricked him into setting himself on fire”—; of Socrates’s wives, how

Xantippe poured a piss-pot on his head.

The silly man sat still as he were dead,

Wiping his head, but dared no more complain

Than say, “Ere thunder stops, down comes the rain.”

Next of Pasiphae, Queen of Crete, and her “horrible lust;” then of Clytemnestra’s lechery And how she made her husband die by treachery. He read that story with great devotion.

Then of Amphiarus, whose wife, Eriphyle, betrayed him to the Greeks; of Livia and Lucillia, who poisoned their husbands;

Of wives of later date he also read,

How some had killed their husbands when in bed,

Then night-long with their lechers played the whore,

While the poor corpse lay fresh upon the floor….

He spoke more harm of us than heart can think…

The Wife stood it as long as she could, but finally

When I saw that he would never stop

Reading this cursed book, all night no doubt,

I suddenly grabbed and tore three pages out

Where he was reading, at the very place,

And fisted such a buffet in his face

That backwards down into our fire he fell.

The Wife received a blow on the head in return, and “We had a mort of trouble and heavy weather,” but in the end they made up, her husband gave her “the government of the house and land,” told her to do as she pleased for the rest of her life, and burned the book. And the Wife concludes triumphantly: “From that day forward there was no debate.”59