One of the best-known figures of medieval literature is the lady of the castle, the heroine of romance. An example of the type is Blonde, of Jehan et Blonde, by Philippe de Beaumanoir, a poetically gifted lawyer who in a more serious vein drafted the important thirteenth-century legal code, the Customs of Beauvais. His hero Jehan is a French knight who goes to England to seek his fortune and falls in love with Blonde, the daughter of the Count of Osenefort, his patron. Blonde’s hair is, of course, golden, her forehead white and smooth, her eyebrows dark, straight, and delicately traced, her nose neither too small nor too large, her eyes gray and clear and sparkling, her mouth dainty, her teeth small and perfect, her breath sweet, her neck so white that when she drinks red wine one can see it flow down her throat, her arms slender and shapely, her hands graceful, with long, straight fingers, her breasts small, her waist narrow, her feet well made. Serving her at meals, Jehan becomes so distracted that he falls ill.

When Blonde learns of Jehan’s plight, she promises to love him, but when he recovers explains that she only promised in order to make him well. “You cannot imagine that I would give you my heart; it would be too great an abasement,” the highborn heroine explains. At that Jehan falls ill again, and this time Blonde overcomes her scruples and cures him by a kiss from “her sweet mouth.”

Two years pass in which Jehan and Blonde love (but chastely); then a messenger brings news from France that Jehan’s father is dying. Jehan hastens home to do homage for his fief to the king of France. When he returns he finds Blonde about to be betrothed by her parents to one of the wealthiest lords in England. The lovers flee to France, where they are married; King Louis raises Jehan to the rank of count, gives him rich fiefs, and reconciles him with Blonde’s father. At Pentecost the reunion is celebrated with a great feast in the presence of the king and queen of France.1

There is little doubt about the inspiration for Philippe de Beaumanoir’s tale. During the early 1260s he served as a squire in the household of the great French-English rebel Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester. The original of Blonde was Eleanor de Montfort, youngest daughter of King John, and sister of King Henry III. Like Jehan, Simon was a French knight; like Blonde, Eleanor was a highborn English lady. But Eleanor’s real-life story, though not lacking in romance, was less about love than about money and power, and her role was not sweetly passive like that of Blonde. A woman of strong will with an eye for her own interests, she ably seconded her husband’s political ambitions, commanded his castle against his enemies, and pursued her own property claims with an unyielding obstinacy that actually delayed for two years an important peace treaty between France and England.

Born in 1215, the year of Magna Carta, Eleanor was a yearold when King John died and her nine-year-old brother Henry acceded to the throne. Eleanor was sought in marriage at an early age by one of Henry’s chief vassals, William Marshal II, Earl of Pembroke. After lengthy debate by Henry’s counselors over the advantages and drawbacks, the ceremony took place in 1224, when she was nine and William was in his early thirties.

She was sixteen and childless when William was taken suddenly and fatally ill. At the time of the marriage, Henry, as her guardian, had settled on her a dowry of ten manors with an income of just over two hundred pounds a year, hers for life in the absence of children. That was a trifle compared to her dower, her share of the vast Marshal estates in England, Wales, and Ireland. By feudal law she was not William’s heir, nor was there any sense of community property. If the marriage had produced sons, the eldest would have inherited; if only daughters, the estates would have been divided among them. Since it produced no heirs at all, William’s eldest brother Richard inherited. But Magna Carta had codified what had long been custom: the widow was entitled to a third of all her husband’s lands for her lifetime.

The dower third was supposed to be turned over to the widow within forty days of the husband’s death, but the Marshal case proved knotty and Eleanor’s dissatisfaction with the outcome became a lifelong obsession. The enormous extent of the lands aroused rather than assuaged greed. Richard Marshal even seized household furniture willed to Eleanor, tried to appropriate manors from her dowry, and sought to shift the estate’s debts to her.

As a substitute for land in settling the Irish estates, King Henry, as his sister’s guardian, eventually accepted a payment of four hundred pounds a year, a figure Eleanor criticized as too low; besides, Richard and his heirs proved laggard debtors. Exasperated, Henry advanced money to his sister himself, andher rights in England and Wales were at length similarly settled for yearly income of five hundred pounds.

Meantime Eleanor had rashly allowed herself to be persuaded by her governess and companion, Cecily de Sandford, also recently widowed, to join her in a vow of chastity, rendered the more binding by a ceremony conducted by the Archbishop of Canterbury, whereby the two women put on wedding rings to symbolize their marriage to Christ. Though adopting a nun’s habit of homespun, they stopped short of assuming veils.

Cecily’s chastity evidently suited her, because she kept her vow and on her deathbed refused to surrender the ring even to her confessor. Spirited Eleanor, still in her teens, began to tire of perpetual continence and homespun clothing. Without ever abjuring her vow, she reverted to the life of a lady, traveling with her retinue from one of her manors to another, and frequently visiting her brother’s court.

In 1236 she was in Canterbury for the celebration of Henry’s marriage to Eleanor of Provence. Among the barons performing ceremonial duties was twenty-eight-year-old Simon de Montfort. Simon had just arrived from France to press a claim to the earldom of Leicester, which had been granted to his father by King John, had reverted to the crown on his father’s death, and had been re-granted by Henry III to Simon’s cousin the Earl of Chester as part of a general shuffling of French and English holdings by royal vassals. Simon had a great name, his father having commanded the Crusading army that crushed the Albigensians, but he had at the moment little else. A second son, he had persuaded his older brother to resign to him the Leicester claim, which to everyone’s surprise he made good—thanks apparently to his formidable personal charm.

In his own words,

[I] prayed my lord the king that he would restore to me my father’s inheritance. And he answered that he could not do it because he had given it to the earl of Chester and his heirs by charter…. The following year my lord the king crossed to Brittany and with him the earl of Chester who held my inheritance. And I went to the earl at the castle of St. Jacques-de-Beuvron which he held. There I prayed him that I could find his grace to have my inheritance…. The earl graciously agreed and the following August took me with him to England, and asked the king to receive my homage for the inheritance of my father, to which, as he said, I had greater right than he, and all the gift which the king had given him in this he renounced….2

Henry III, brother of Eleanor de Montfort, effigy in Westminster Abbey. National Monuments Record.

Whatever accounts for the Earl’s unbaronlike generosity, Simon became at a stroke one of the great magnates of England, and soon after a court favorite.

Simon and Eleanor had probably met before the royal wedding. In any case, far from being fatally stricken by her beauty, like Jehan in the romance, Simon continued to pursue two marriage projects with Continental heiresses. Only when both failed—one, with the Countess of Flanders, through the intervention of Blanche of Castile—did Simon turn his attention to Eleanor.

Eleanor meanwhile had wheedled a castle out of her royal brother. Odiham, northeast of Winchester, built by their father, King John, as a hunting lodge, consisted of an octagonal tower with a basement on the first floor, a large hall above, and on the top floor Eleanor’s chamber. Rather modest as castles went, Odiham nonetheless permitted a life-style that soon left its mistress short of cash and borrowing from the king.

She was twenty-one years old when Simon turned an interested eye on her. Reconnaissance was followed by action. The courtship remains the intriguing mystery it was to their contemporaries, but was clearly carried on in a quite different manner from that depicted by Philippe de Beaumanoir. Where unrequited love made Jehan ill, Simon turned on his practiced charm and evidently encountered little resistance.

Early in 1238 word leaked out that Eleanor and Simon were married. The ceremony had been performed in secret in the king’s private chapel during Christmas court at Westminster. The scandal was not only as spicy as it was startling—few had difficulty in finding an explanation—but potentially dangerous. If a foreign adventurer had, by a means congenial to adventurers, assured himself of the property, power, and status of a king’s sister which properly belonged either to a native magnate (like William Marshal) or to a royal suitor (both Eleanor’s sisters had married kings), then the barons, jealous of their rights as royal counselors, had been hoodwinked. Besides, there was Eleanor’s vow of chastity, which at least the English clergy took seriously.

What exactly had happened? Did Eleanor confide to her brother that she and Simon were lovers? Did a third party give him information? However he found out, Henry probably also concluded that Eleanor was pregnant, so that there was no time to be lost. He decided it was safest to confront the barons with a fait accompli. They predictably took offense at what Richard of Cornwall called the “underhanded marriage,”3 but Simon successfully cajoled Richard with flattery and gifts, and the other barons grumbled and gave in.

That left Eleanor’s vow of chastity. Some clerics flatly refused to recognize the marriage and stuck to their refusal. The monk who wrote the Annals of Dunstable referred to Eleanor only as “countess of Pembroke” or “the king’s sister,” never as “countess of Leicester” or “Eleanor de Montfort.” In the spring, “seeing that the hearts of the king and Earl Richard, as well as those of all the nobles, were estranged from him, and finding that the marriage which he had contracted with the king’s sister was looked upon by many to be, as it were, annulled,” wrote Matthew Paris, Simon borrowed heavily and sailed for Rome, “hoping by means of his money … to obtain permission to enjoy his unlawful marriage. The countess of Pembroke in the meantime lay concealed, in a state of pregnancy, at Kenilworth castle, awaiting the issue of the event.”4

Temporarily granted to Simon and Eleanor by Henry, the royal castle of Kenilworth was one of the finest in England, an imposing Norman keep of red sandstone surrounded on three sides by an artificial lake. Eighty by sixty feet in plan and eighty feet high, the keep had square projecting turrets at the corners and a battlemented forebuilding. The amenities included a well with a bucket and pulley, three tiers of latrines to accommodate the castle’s two floors and the upper battlements, a fishpond, and, hugging the wall, outbuildings—kitchen, chapel, storehouses. Eleanor’s comfort was assured by gifts of venison from the king, and “six tuns [barrels] of better wine.”5

Simon returned in October, his papal dispensation granted doubtless in return for bribes (Matthew Paris sarcastically noted that “perhaps … the Roman court had in view something of deeper meaning than we could understand”).6

But gossip received a setback when Eleanor failed to deliver until November 1238, eleven months after her marriage. Henry stood godfather, and the baby was named after him. Whatever Henry’s deeper feelings about the marriage, he was evidently reconciled to it.

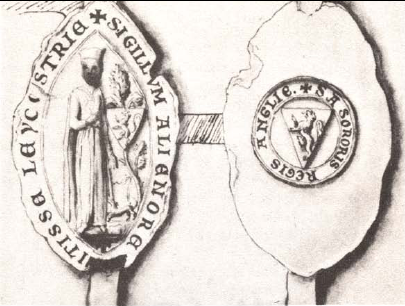

Seal of Eleanor de Montfort reads: “Seal of Eleanor, Countess of Leicester,

Sister of the King of England.”

Bibliothèque Nationale, MS Clairembault 1188, f. 17r.

During Christmas at Winchester he formally invested Simon with the earldom of Leicester and presented Eleanor with elaborate gifts, a robe richly embroidered and trimmed with miniver and feathers, made of “baudekyn,” a material woven with a warp of gold thread and woof of silk; a mantle of scarlet cloth; a mattress for her bed and a coverlet of gray fur lined with scarlet, both packed in canvas and sent to Kenilworth.

The following June when the new queen bore her first child, the future Edward I, Simon was a member of the royal christening party. Eleanor accompanied him to London, where at firstall went well. But in August when the Montforts joined the procession to Westminster Abbey for the queen’s ceremonial purification (“churching”), Henry suddenly turned on Simon with angry accusations. The trouble, according to Matthew Paris, was the king’s discovery that Simon had named him as security for money he had borrowed to bribe Rome for the cancellation of Eleanor’s vow of chastity.

The Montforts withdrew to the palace of the bishop of Winchester, where they were staying, to await the cooling of the royal temper, but it did not cool. Instead, still according to Matthew Paris, the king ordered them evicted, and to their “tears and lamentations” returned a furious answer:

You seduced my sister before marriage, and when I found out, I gave her to you in marriage, although against my will, in order to avoid scandal; and, that her vow might not impede the marriage, you went to Rome, and by costly presents and great promises you bribed the Roman court to grant you permission to do what was unlawful. The archbishop of Canterbury here present knows this, and intimated the truth of the matter to the pope, but truth was overcome by reiterated bribes, and yielded to Roman avarice; and on your failing to pay the money you promised, you were excommunicated; and to increase the mass of your wickedness, you, by false evidence, named me as your security, without consulting me, and when I knew nothing at all of the matter.7

The verbatim accuracy of so long a quote (probably at second hand) may be doubted, but Matthew Paris captured the sense of the king’s resentment, as we know from other sources; that night, to escape a threat of the Tower, Simon and Eleanor boarded a small boat, with only a few servants, sailed down the Thames to the Channel coast, and took ship for France.

They settled in at the Montfort family castle at Montfort-l’Amaury, where a second son, Simon, was born. Perhaps to aidreconciliation with Henry, Simon in 1240 joined Richard of Cornwall and other English nobles on a small Crusade. Eleanor and her two boys traveled with him as far as Brindisi, in southern Italy, where she settled down in a castle lent her by Frederick II, husband of her sister Isabella. She was again pregnant, with a third son, Guy.

In England, Henry gave a sign of relenting by ordering renovation of his sister’s castle and manor at Odiham, completing a kitchen outbuilding which Simon had begun, and building a separate hall and kitchen on the manor. By 1244 he had forgiven his erring brother-in-law and welcomed the pair back to England.

They arrived in time for Richard of Cornwall’s marriage to Sanchia, sister of Queen Eleanor and Queen Marguerite of France. Present was Countess Beatrice of Provence, the mother of the bride and the queen, described by Matthew Paris as “a woman of remarkable beauty.”8 Eleanor and Simon apparently enlisted Beatrice as a court ally, and at the Christmas feast at Richard of Cornwall’s castle of Wallingford, she reminded Henry that he had never given his sister a dowry for her marriage to Simon. Henry responded generously by granting the Montforts a yearly income of five hundred marks, and an additional three hundred marks a year to their heirs. He also arranged to have Eleanor’s dower lands turned over to her if the last of the four Marshal brothers defaulted in his payments; furthermore, he pardoned both Eleanor and Simon for debts to the tune of some 1,750 pounds.

Finally, he granted Kenilworth to Eleanor for life. The castle the Montforts took over had undergone extensive improvements in strength and comfort during their absence. Henry had ordered walls and outbuildings repaired and a new roof for the great chamber. The chapel had been paneled, and the paneling whitewashed and decorated with paintings, with seat of painted wood for the master and mistress. The mistress’s chamber had been paneled and painted, and its fireplace and latrine repaired. Henry had even ordered a “fair and beautiful boat” to be built and anchored at the door of the great chamber.9

Surviving tower of the Montfort family castle at Montfort-l’Amaury. Archives Photographiques.

Relations between the Montforts and the king reached a new plateau of goodwill in the 1240s when the ever-turbulent barons threatened insurrection and Simon skillfully played the role of mediator, gaining prestige with both sides.

Eleanor was now thirty. During this peaceful era in the Montforts’ life they divided their time among Odiham, Kenilworth, and the court, their needs supplied by their manors scattered across England, from which they derived money, grain, meat, fodder, and cloth. As the large household moved from one estate to another, it consumed the produce of the demesne (the land exploited directly by the lord) of each manor in turn. Sale of the surplus added to revenues from rents and fines. All the same, there was a chronic shortage of cash to pay servants and purchase luxuries and necessities—wine, spices, silks, jewels—not raised on the manors. As with many baronial families, borrowing was an integral element of the Montfort domestic economy. Henry sometimes helped out—once by simply canceling a debt of 110 pounds and 11 shillings to David, a Jew of Oxford.

The kitchen accounts listed numbers of oxen, sheep, calves, chickens, pigs, kids, as well as large quantities of eggs, butter, cheese, and milk. The king continued to send them venison from the royal forests. In Lent, besides the staple of salt herring, the castle table displayed salmon, cod, eel, sole, mackerel, sturgeon, and shellfish—oysters, crabs, shrimp. Freshwater fish were supplied by a fisherman and his assistants. Spices, nuts, rice, and dried fruits were purchased in London or at the fairs.

Eleanor’s household staff comprised more than sixty servants, headed by a steward. Except for the laundress, all were male:cook, butler, baker, and with helpers, two chamber boys, several tailors, smiths, carters, messengers, and other outside servants. Two more sons, Amalric and Richard, had been born; each child had his own nurse, of higher status than the servants—one was referred to as “the lady Alice.” Eleanor also had personal attendants who served as her companions.

In her role of hostess, Eleanor entertained royal officials, clerics, Simon’s fellow barons, personal friends. Among the clerics were the distinguished scholar and scientist Robert Grosseteste, bishop of Lincoln, in whose household two of the Montfort sons were educated, and the abbot of Waverly, ten miles from Odiham, the first Cistercian monastery in England, where on Palm Sunday in 1246 the Montforts attended mass, Eleanor bringing the gift of a costly altar cloth.

Another clerical friend, a Franciscan monk named Adam Marsh, wrote the Montforts letters that shed some light on their personalities as perceived by others. An Oxford lecturer and a preacher whose outspoken sermons to the royal court often offended the king, Brother Adam was not afraid to give the earl and the countess frank advice. Both evidently suffered from shortness of temper. He cautioned Simon, “Better is a patient man than a strong man, and he who can rule his temper than he who storms a city.”10 In a letter to Eleanor prefaced by an apology for brevity that did not prevent him from going on for several pages, he warned her about the “demoniacal furors of wrath that do not shrink from disturbing the most loving peace of marriage,” quoting the Old Testament (Job 5:2), “For wrath killeth the foolish man, and envy slayeth the silly one.” He sermonized on:

Truly now, gentleness is dispelled by wrath, our likeness to the divine image is marred, wisdom is lost, life is lost, justice is relinquished, partnership is destroyed, peace is broken, truth is obscured. Through wrath are strife, disturbance of mind, con-

Norman keep of Kenilworth Castle, granted to Eleanor de Montfort by her brother Henry III in 1244, and defended by her son in a memorable siege in 1265 Department of the Environment. tumely, clamor, indignation, pusillanimity, and blasphemy brought forth. Wrath makes the heart pound, impels us against our nearest relations, drives the tongue to curses, creates havoc with the mind, generates hatred of our dearest, and dissolves the covenant of friendship.

He advised Eleanor to banish this pestilence from her soul before it dragged her into the pit, and to submit herself to “the most placid grace of the most pious Virgin Mary.”

The letter continued, mingling adjurations to meekness with a lecture on a favorite clerical subject, the evils of ostentation in dress, in the words of Saint Peter (I Peter 3:1–4): “Likewise, ye wives, be in subjection to your own husbands … whose adorning let it not be that outward adorning of plaiting the hair, and of wearing of gold, or of putting on of apparel; but let it be … in that which is not corruptible, even the ornament of a meek and quiet spirit, which is in the sight of God of great price.” He appended another text (I Timothy 2:9–10), recommending that women “adorn themselves in modest apparel, with shamefacedness and sobriety; not with braided hair, or gold, or pearls, or costly array; but … with good works.” Finally he urged Eleanor to use her influence to moderate Simon’s behavior. 11

In another letter he enigmatically informed Eleanor that he blushed to hear evil reports about her; “I ask, I advise, I adjure you” to behave in such a way as to put a stop to the gossip.12 Although Eleanor’s spirit was far from meek and quiet, she accepted Brother Adam’s moralizing in good part, and Simon named him one of the executors of his will.

In 1248 Henry appointed Simon to the high post of seneschal (governor) of Gascony. The Montforts sailed to Bordeaux, where Eleanor bore a daughter who died in infancy. Simon’s governorship was not an unqualified success, his alleged highhandedness drawing so many protests that in 1251 Henry recalled the Montforts to England for an interview which turned into another noisy quarrel. Nevertheless Simon returned to Gascony, leaving Eleanor at Kenilworth. She was again expecting, and another daughter, Eleanor, was born in the fall of 1252.

Despite his Gascon troubles, Simon was one of the negotiators in 1257 at the preliminaries to a major treaty with France, looking to the relinquishment by Henry, in return for an annual payment, of claims to French provinces that had once belonged to the English crown. Simon encountered one serious obstacle in the negotiations: his own Eleanor, whose simmering dissatisfaction with the way her Marshal dower had been handled now surfaced. As King John’s surviving daughter, Eleanor had to give her consent to the surrender of the family claim to the lost French lands. She refused to do so until something was done about her dower, for which she insisted she had never been adequately compensated.

While Eleanor stubbornly blocked the treaty, her brother Henry foolishly rekindled the quarrel between crown and barons. He had concluded an agreement with the pope by which his youngest son, Edmund, was to be named king of Sicily in return for Henry’s financial backing of a military expedition against the pope’s enemy, Frederick II’s illegitimate son Manfred. The barons had no objection on principle to the worldly bargain, but were shocked by the sum, 135,541 marks, which presaged extraordinary tax levies. Henry’s attempts to raise the money escalated into a crisis, and in 1258 Simon played a leading role in the resolution of the affair. The result, however, was not a compromise of differences, as a decade earlier, but a humiliating defeat for the monarch, who by the Provisions of Oxford agreed to accept a permanent council chosen by the barons to oversee his administrative functions. In the negotiations, a subtle but significant shift took place in Simon’s position. From the king’s counselor he moved to mediator between the two sides, and ultimately emerged as spokesman for the barons, who began to acknowledge him as their leader.

Meantime Eleanor started a new legal battle, this time against her stepbrothers and stepsisters, offspring of her mother Isabelle of Angoulême’s second marriage. Isabelle had divided her inheritance among her second family, ignoring the claims of her first. Eleanor now began a lengthy litigation for her share of her mother’s estates.

Early in 1259 Henry, his brother Richard, and their sons all renounced their French lands. Obstinate Eleanor held out, arguing that she had been cheated of two-thirds of her dower income for the last twenty-seven years, and demanding the arrears. Henry bestowed ten more manors on her, and though she remained far from reconciled, she signed the treaty, with the stipulation that fifteen thousand marks of the compensation due Henry be held in escrow for two years until her dower was settled to her satisfaction.

While Eleanor fought for her personal claims, Henry sought to overturn the constitutional revolution of the Provisions of Oxford, and in 1262 obtained a papal bull revoking them. The barons refused to accept the pope’s verdict and turned to Louis IX for arbitration, but meanwhile prepared to fight. In 1263 Simon de Montfort took his family to visit the king in London for several months, apparently in an attempt to mediate the quarrel. But late in the summer Eleanor and the children ominously returned to Kenilworth, which Simon had strengthened with siege machinery brought over from France.

In January 1264 Louis IX announced his decision on the Provisions of Oxford, which he found incompatible with royal authority. Untroubled by the fact that Louis had been their arbiter, the barons at once took the field, with Simon as theircommander. The two armies, baronial and royal, met in battle at Lewes, near Brighton. Pitched battles were uncommon in the warfare of the Middle Ages, and when they occurred the outcome was likely to be unpredictable and decisive. At Lewes, Simon and the barons won a dramatic victory, the king, his son Edward, and his brother Richard of Cornwall all becoming Simon’s prisoners.

That Christmas, the Montforts celebrated at Kenilworth with royal splendor, almost as if Simon were king and Eleanor queen, entertaining alike allies and associates of doubtful loyalty, as well as their royal captives.

The dazzling Montfort triumph proved momentary. Success was fatal to baronial unity, while forces loyal to the king rallied. In March, after a “parliament”—a meeting of magnates prefiguring the later institution—that aired some of the divisions, the Montfort family gathered for a last reunion at Odiham before the renewal of war. On April 2 Simon took leave of Eleanor and went off to marshal his forces in Wales.

On the home front at Odiham, Eleanor continued to entertain numerous guests: the abbot of Waverly, the prioress and nuns of the convent of Witney, who embroidered an Easter cape for her chaplain, the prioress of Amesbury, local knights and ladies. She ordered a miniver-trimmed Easter robe for her daughter, as well as two pairs of shoes, twenty-five gilded stars to decorate her cap, a black satin hood, and a scarlet robe. At one point the daughter was evidently ill, for a horse was sent to Reading to bring back a barber to bleed her.

At the same time, Eleanor sent presents to her captive relatives: eels, hakes, and figs to her nephew Edward, now confined at his own castle of Wallingford; spices, wine, and scarlet cloth for her brother Richard of Cornwall, still a prisoner at Kenilworth; a robe, tunic, and cloak of “rayed” or striped cloth for Richard’s son Edmund.

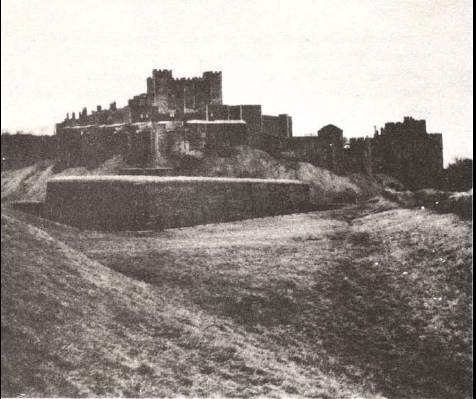

Dover Castle, the Channel stronghold commanded by Eleanor de Montfort in 1265. Department of the Environment.

In June Eleanor moved on to the castle of Portchester, near Portsmouth, and finally, escorted by her son Simon at the head of a strong force and accompanied by a train of hired or borrowed horses and carts, to the great castle at Dover. Some of her baggage was even sent by sea, indicating the intention of a prolonged stay at this major stronghold. It was important to keep the support of the strategic Channel coast towns, and in Winchelsea she stopped to entertain the leading citizens, feasting them on two oxen and thirteen sheep. Three days after her arrival in Dover she invited citizens of Sandwich to dinner, anda month later the burghers of both Winchelsea and Sandwich were once more entertained.

Leaving his mother in command of Dover, young Simon led his own band off to Kenilworth, where his father was to join him. As the summer passed, provisioning crowded Dover became a problem. Wagons and boats were sent out to bring fodder and food. By August Eleanor’s manors could no longer provide meat for the castle, and oxen and sheep were obtained by foraging.

Suddenly that problem lost its urgency. Early in August messengers brought news of catastrophe. Simon’s army had been surprised and routed near the abbey of Evesham. Simon and their son Henry were killed.

Overcome by shock and grief, Eleanor donned mourning and refused food for several days. Then she pulled herself together and sent a message to her brother seeking reconciliation. Henry did not reply.

Her sons wanted to keep on fighting. On August 11 Richard, the youngest, arrived at Dover by sea at the head of a hundred men, while young Simon, in command of the garrison at Kenilworth, prepared for a siege.

In September a parliament met at Winchester. Distraught Eleanor sent messengers but got no more reply than she had from the king.

The baronial cause was clearly lost and with it the Montfort family fortunes. Eleanor still held two cards: the royalist prisoners in Dover Castle, now hostages for her own safety, and a large sum of money, the war chest collected by the barons and entrusted to her keeping. Henry had ordered the Channel ports closely watched, but Eleanor succeeded in getting Richard, Amaury, and the money out of Dover and across the Channel. She was less successful with her own household belongings, which were captured by pirates.

In October the hostages bribed their guards, freed themselves, and attacked the garrison from within while Prince Edward launched an assault from outside. The disheartened garrison was overpowered, and Eleanor forced to surrender. Edward, more generous or less aggravated than his father, agreed to receive back into his favor the chief followers of “his most dear aunt, the lady countess of Leicester.”13 He even agreed to restore the lands of these lesser rebels, but Eleanor and her children were sentenced to banishment and confiscation. At the end of October she and daughter Eleanor sailed from Dover to take up residence, like a pair of wealthy penitents, in the Dominican convent of Montargis, south of Paris. She was fifty years old.

At Montargis in the following year (1266) she received the news of the prolonged siege of Kenilworth, where young Simon, refusing generous terms and holding out to the bitter end, was finally overcome by starvation and dysentery among his men. Even as the castle surrendered in December, Simon escaped, hid out in the fen country for months, and eventually made his way to France.

Eleanor, far from retiring from the world, made the convent at Montargis a new headquarters to fight her legal battles, with more success than the family had enjoyed in the civil war. The French parlement in 1267 decided the case of her claims on her mother’s land in Angoulême in her favor; when her stepbrother the Count of La Marche was slow in paying, Eleanor successfully appealed to Louis IX, who ordered the count to pay up and directed his seneschal to enforce the order.

Louis went further, sending arbiters to England to mediate Eleanor’s English claims and obtaining generous terms: young Simon was to be allowed to resume possession of his father’s lands, with the stipulation that the king or one of his sons could purchase them at a price set by Louis. Eleanor was to have five hundred pounds a year for her dower lands in England. For amoment reconciliation seemed at hand, but Henry, after agreeing to the settlement, refused to carry it out. Backed by Louis, Eleanor took her case to the Papal Curia, where Pope Clement promised her a hearing despite Henry’s objection.

At this point Eleanor’s sons Simon and Guy put an end to all hopes by a foolish act of violence. In Italy to seek their fortunes, they waylaid Henry of Almain, Richard of Cornwall’s son, in a church in Viterbo, killing him in revenge for what they regarded as his treachery to their father’s cause. Simon died in hiding within a year, and Guy later in a Sicilian prison.

In 1272 the aging Henry III died at Westminster. Prince Edward, now Edward I, returning home from Louis IX’s last Crusade, wrote his chancellor from France: “We … have remitted to Eleanor, Countess of Leicester, all indignation and rancor of our mind which we had conceived against her on account of the disturbance lately had in our realm, and we have admitted her to grace and our firm peace.”14 Eleanor was to be allowed to plead against the king or anyone else for her rights. During his stay in Paris, generous Edward loaned his aunt, as usual in need of cash, two hundred pounds. Soon after, he restored her dower lands and ordered the Marshal heirs to answer to the Exchequer for the money they owed Eleanor.

Eleanor briefly enjoyed her improved financial condition before dying on Easter Eve, 1275, at the age of sixty, in the convent of Montargis. Not until nine years later were final payments made settling the law case she had pursued through the courts of England and France for forty-four years.

Eleanor’s daughter and namesake, betrothed before Simon’s death to Prince Llewelyn of Wales, sailed from France with her brother Amaury late in 1275, but was intercepted by King Edward who saw their arrival as a threat. He imprisoned Amaury in Corfe Castle and kept Eleanor under surveillance at court for three years before allowing her to marry Llewelyn. She interceded for her brother’s release “with joined hands, bent knees, and tearful sobs,”15 and in 1282 her brother was freed. Two months later Eleanor died in childbirth. Her daughter was brought up in England by nuns of the order of Saint Gilbert of Sempringham, where she lived in obscurity until her death in 1337. Amaury never regained his English estates. By the end of the century the entire Montfort family had disappeared.

So ended the story, not lacking in drama, romance, and tragedy, but also including avarice, banality, and pettiness, of the real-life model of a heroine of medieval romance.