“In making cloth she showed so great a bent/She bettered those of Ypres and of Ghent,”1 says Chaucer of his Wife of Bath. Women throughout history have plied the several arts of clothmaking, but in the Middle Ages they came for the first time to play an outstanding role in a commercial textile industry. Ypres and Ghent were two of the principal cloth towns of Flanders, a region of northwest Europe favored by nature for textile manufacture. Lying just across the Channel from the pastures where England’s long-fleeced sheep grazed, Flanders possessed a soil that was congenial to dye plants, contained an abundance of fuller’s earth, and was watered by streams needed for cloth finishing.

As clothmaking made the momentous transition from home industry to organized production for profit, men took over most of the looms and many of the other functions, but women did not retire from the trade. On the contrary, the major part of thepopulation of every Flemish and Italian cloth town, men, women, and children, was conscripted into the new “putting-out system.” An insight into the operation of this historic medieval innovation and its social implications for women and men is furnished by a unique parchment document of about 1286, found in the town hall of Douai (now in France, then in Flanders), that attests to the thirteenth-century existence of, among others, Angnies (Agnes) li Patiniere, daughter of Druin le Patinier and wife of Jehan Dou Hoc. Consisting of eleven sheets sewn together end to end in a roll five and a half meters long, the document is the minutes of a legal proceeding against the estate of Agnes’s employer, Douai wool merchant Jehan Boinebroke, by forty-one of his former workers and some others. Agnes’s family were in the textile-dyeing branch of the wool-cloth industry, specializing in the blue dye extracted from the leaves of the woad plant. Dyeing was occasionally done while the wool was in its original raw form (“dyed in the wool”) but typically either the spun yarn or the woven cloth was treated by dipping in a tub of hot water containing the dye matter along with alum, a fixative, and wood ashes as a tempering agent. Despite using wooden poles, the men and women in the trade were universally recognized by the color under their fingernails.

Agnes’s family probably lived on the edge of a canal fed by the Scarpe river that runs through the center of Douai, in a two-story wooden dwelling little different from the thousand others that housed the town’s labor force. Like all medieval cities, Douai presented an aspect somewhat like that of a nineteenth-century small town of the American Midwest, though compressed by walls into a narrower space: half-urban, half-rural, with barns and stables, garden patches, orchards, fields, and public wells interspersed amid the jumble of rude dwellings that crowded the narrow streets and quais. In each house one or more families shared space with loom, stretching frame, or other equipment.

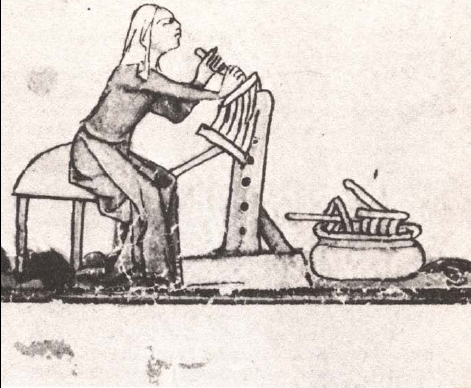

Woman carding (combing) wool. British Library, MS Royal 10 E VI, f. 138.

Boinebroke, in contrast, occupied a large house near the Porte Olivet, in Neuville, the more recently settled upper town where most of the wealthy patricians lived. Behind the house, on the canal, stood his own dyery, and near it an establishment for stretching cloth. He also owned a number of workers’ houses which he rented (one of the plaintiffs in the suit was a tenant whom he had cheated). His rental properties were scattered throughout Douai: in the old lower town where the city had begun, on the Rue des Foulons (Fullers Street); in the marshy, low-lying quarter between lower and upper towns, where willows shaded the riverbanks, and where Boinebroke rented awhole block of houses to his workers; and in the upper town where he himself lived.

Of the twenty-five or more crafts associated with the cloth industry (spinning, weaving, cleaning, carding, shearing, fulling, stretching, dyeing, and various auxiliary functions), some were male-dominated, some female, some mixed. Spinning, still done by distaff (the spinning wheel first appears late in the thirteenth century), remained almost wholly in the hands of women, together with many of the finishing processes, a division of labor destined to last for centuries. Dyeing and weaving were done by men and women more or less interchangeably. Twenty of the forty-one employees mentioned in the legal proceeding against Boinebroke were women. But more significant than the sexual division of labor was the familial labor force of the medieval wool industry, the association of a family group as a work unit in the putting-out system.

A Flemish entrepreneur like Boinebroke bought raw wool in England, shipped it home, parceled it out to a family to clean, spin, card, and weave, took it back and gave it to another to full, then to another to dye, and to another to stretch, tease (raise the nap), and shear. Retrieving it for the last time, he gave it to an agent to sell, typically at the nearby Flemish or more distant Champagne fairs. The working unit was not necessarily a conventional family with father, mother, and children, but might be a pair or trio of sisters, or brothers and sisters, or mother and daughters.

Work was from dawn to dusk, six days a week except for feast days, regulated by the “workers’ clock” in the town hall which sounded the “morning chime,” noon and afternoon “chimes for eating,” and the vesper or “quit-work chime.” In other respects, too, work was strictly regulated. Though in form the weavers were independent craftsmen and craftswomen, buying the raw wool from the entrepreneur and selling him back the woven cloth, they were actually proletarian pieceworkers whose factory was scattered through the town. The minute specialization of their labor was enforced in the interest of their employers, who wanted all operations uniform. Finally, to hold labor costs down by keeping the workers in a state of dependency, they were forbidden to work for anyone except their own entrepreneur, who sat with his fellow merchants on the town council and ran the government.

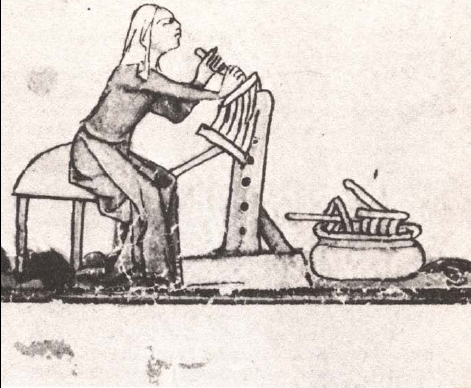

Women carding and spinning, using the late-thirteenth-century invention, the spinning wheel. British Library, MS Add. 41230, f. 193.

The system also protected the merchants against loss through market fluctuations, war, or other calamity since at any point in the process of manufacture the entrepreneur could simply opt out, leaving the weaver, fuller, or dyer with the cloth on his hands.

Not surprisingly, the putting-out system bred class conflict. History’s first strike, in 1245, was recorded among Douai’s weavers, and numerous proletarian protests bloodied the streets in the cities of Flanders and Italy throughout the high Middle Ages. The largest insurrection was that of the washers and carders known as the Ciompi in Florence in 1378. The lowest-level workers in the Florentine wool-cloth industry, the Ciompi were so called because of the wooden clogs they wore at work. Joined by other workers, including numbers of women spinners, warpers, and weavers, they momentarily seized power, but, thwarted by the adhesion of small craftsmen to the side of the big merchants, were routed in street fighting and suppressed as a political force.

In Douai in 1322 a much smaller conflict reflecting the same class divisions and outcome is shown in the recorded punishment of eighteen workers, including two women, who “in the full marketplace” had urged assault on grain merchants for hoarding supplies. Charged with being especially vocal, the two women had their tongues cut off before being banished from the city for life.

The document recording the legal proceedings against Boinebroke to which we owe knowledge of Agnes li Patiniere is richer and more revealing of the operation and inequities of medieval industrial society. Agnes is one of forty-five plaintiffs (forty-one employees of Boinebroke, four having other relations with him), all members of the Douai working class, who claimed varying sums owed for unpaid wages, overpriced materials, underpriced payment for the finished product, property unfairly seized, and unjust evictions. Boinebroke emerges from the testimony of plaintiffs and witnesses as a cynical exploiter who never missed an opportunity to rob a widow or cheat an orphan. Not all medieval businessmen were scoundrels, but the system, political as well as economic, provided an untrammeled arena for rugged individualism.

Agnes’s complaint was on behalf of her mother Mariien, from whom Boinebroke had seized a vat of dye in payment of a debt of her late husband. The vat, according to Agnes, was worth twenty pounds more than the debt. To support her deposition she brought to court Jehanain As Cles, Saintain Caperon, and Isabelle le Françoise, who took their oaths, as did Agnes, on the holy relics, and confirmed her story. Their testimony drew a lively verisimilitude from their recollections of the words used by the domineering capitalist in rebuffing Agnes’s mother when she appealed to him: “Granny (Conmère), go and work in the tannery, since you need money; I hate to see you like this!” She tried to appeal to his religious feelings, pleading, “Sire, if you want to treat me right and reward me out of pity, you’ll be doing the same as giving alms, because I’m in need!” To which Boinebroke derisively replied, “Granny, I don’t know what I owe you, but I’ll put you in my will.”2

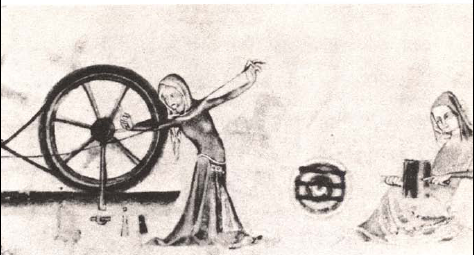

Women weaving. British Library, MS Royal 17 E IV, f. 87V.

Although he spoke roughly to both men and women and was capable of reducing men to tears, his sharpest retorts seemed to be reserved for women, whether his employees or not. A woman cloth-stretcher who tried to collect rent from him received the threat, “Granny, if you take a lien on my property, I’ll have you fined 60 pounds!”3 Another woman who complained that construction he had undertaken on a house next to hers had done extensive harm to her own house was told, “Shut up! The business you do isn’t worth the price of damages!”4

One of the largest claims was made by the widow of a Boinebroke agent, herself a cloth worker. Her husband, before leaving for the Champagne fairs with a consignment of his employer’s cloth, had assured her that he was leaving her well off, that he had just had an accounting with Boinebroke and owed him no more than 12 pounds, plus 32 pounds for a sack of wool. The agent died at the fair. Boinebroke summoned the wife to his house and took her into his counting room, where he handed her a document showing that she owed him a staggering 131 pounds. To her protests, he replied only with assurances that he would make her “a good and faithful accounting.” To pay the debt the widow had to sell her property and turn to her relatives for help. Boinebroke then claimed a second debt of 32 pounds, evidentlyfor the sack of wool. “Sire, for God’s sake,” the widow cried, “why do you demand so much from me? You are doing me a great wrong.” Boinebroke only reiterated that he would give her “a good accounting.”5

From two other dyeresses besides Agnes’s mother, Boinebroke claimed debts so large that they were forced to sell their cloth to him to raise the money, and he took care to buy at a price well below market value.

The court ordered the Boinebroke estate to pay at least part of a great number of claims—Agnes li Patiniere received 100 sous (five pounds)—demonstrating a capacity for justice on the part of the exploiting class that mitigates some of the harshness of the image of Boinebroke.

Yet the most significant point about the Boinebroke document is its revelation of the hold over the workers that the putting-out system, with its rigidly maintained restrictions, provided for an entrepreneur. Several of the claims dated back many years, the claimants not having dared to sue while their oppressor was alive lest he refuse to give them any more work. “I took wool to my lord Jehan and I lost greatly by it,” one woman worker told a witness, who asked, “Since you lost, why did you take it?” “Because I could not do otherwise!”6 Boinebroke’s relationship with his employees was signalized by the terms in which the witnesses described his actions. He “summoned” them to his house, which served as residence, office, warehouse, and salesroom; he issued “commands;” he “required” them to do such and such; he “led them into his chamber,” where he questioned them, made accounts, presented them with bills. In contrast, their posture toward him was that of supplicants; they implored him—”For God’s sake,” “For mercy”—and tried to appeal to his heart. Boinebroke’s death at last freed the workers to seek another employer, and thereby freed them also to sue for their losses.

To supplement the civil power liberally brandished and wielded without constraint by Boinebroke and his fellow businessmen, the power of the Church was sometimes employed. Florentine clothmakers obtained pastoral letters from their bishops to be read in the parishes threatening censure and even excommunication to careless spinsters who wasted yarn. But for most women as for most men in the cloth industry, threats and exploitation were lesser evils than the specter of unemployment. When war or depression hurt the cloth market, the town-factories of workers were turned into encampments of beggars—men, women, and children who poured from their hovels daily to throng the streets and crowd the church doors crying for alms.

In the cloth industry being a woman was no serious disadvantage, but it was no advantage either. Were Agnes and her sisters of Douai, Ghent, Ypres, Bruges, and the other great cloth towns worse off than the peasant women of the medieval countryside? They were probably better off than the landless laborers; no worse off than the bulk of the peasantry, whose livelihood was largely at the mercy of elements beyond their control; and not so well off as the more affluent free peasants who owned a few animals and were exempt from heavy labor services.

They were also not as well off as many of their sisters in other crafts. The mass of medieval townswomen, like medieval countrywomen, worked as a matter of course. A married woman usually worked at her husband’s trade, but might work at a trade of her own. Widows were a universal element in the city crafts. Daughters as well as sons served as apprentices. From time immemorial girl children had learned sorting, cleaning, carding, and spinning, and in the Middle Ages they undertook these arts both for home use and as part of a production system, as in the Flemish wool industry. Like boys, girl apprentices usually took an oath not to get married, frequent taverns, reveal tradesecrets, or rob their masters, though the marriage prohibition might be waived for a money payment.

A single woman working at a craft was known on both sides of the Channel as a femme sole, and enjoyed a status of recognized equality, as did married women who worked at crafts other than their husbands’. These latter were subject to widespread regulations providing immunity for their husbands in case of litigation—”if she be condemned she shall be committed to prison till she be agreed with the plaintiff, and no goods or chattels that belongeth to husband shall be confiscated,” reads an English statute.7 Although doubtless written mainly for the husband’s benefit, the rule was, in Eileen Power’s words, “a notable advance in the position of married women under the common law.”8

Outside the textile industry, centered in Flanders and Italy, and apart from domestic service, working women were employed mainly in two great groups of trades. The first consisted of the hundred-odd crafts—shoemaker, furrier, tailor, barber, jeweler, chandler, mercer, cooper, goldsmith, baker, armorer, hatmaker, saddler, harnessmaker, glovemaker—in which women worked side by side with men, usually, but not always, their husbands. In some they dominated or even monopolized the work—as in the silkmaking crafts of Paris and London. By mid-fourteenth century, London’s “silkwomen” were sufficiently self-conscious and self-confident to deliver a written protest to the mayor and the aldermen against the alleged machinations of Nicholas Sarduche, a “Lombard” (Italian), affecting the price of silk. A century later, in 1455, their great-granddaughters petitioned for the prohibition of imported silk, and got a restrictive tariff act passed.

The second great group of women workers clustered around the manufacture and sale of food and beverages. Like the village women, city women brewed beer and ale (“brewsters” and “alewives”). Malt beverages were in tremendous demand in non-wine-producing countries, notably England, and not infrequently abused—city women were warned by the moral manuals of the time not to be seen drunk in the streets and taverns and not to sit up too late drinking ale even at home.

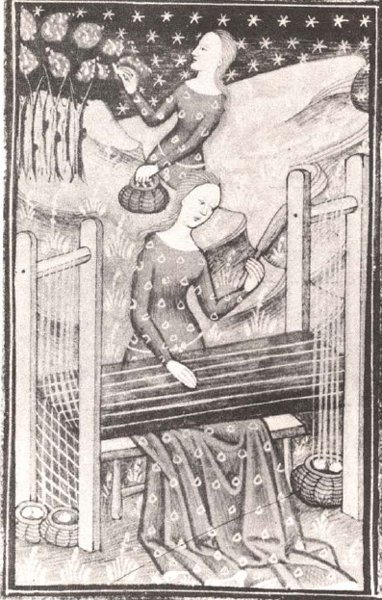

Women silk workers; the silk making crafts were dominated by women. British Library, MS Royal 16GV, f. 54v.

In the fourteenth century, a London brewer bequeathed his daughter five quarters of malt and the lease of a brewhouse for eight years to set herself up in business. By the time of Henry V (reigned 1413–1422) thirty-nine women were listed in the livery of the London Brewers’ Company. As in the villages, city women were often given the post of “ale conner” to check the quality of the guild’s product in the interest of the common reputation; the Ordinances of Worcester specified that the two conners should be “sadd and discrete persones.”9 The London assayer of oysters made a practice of farming his similar office to women.

The famous Margery Kempe, daughter of a mayor of Norwich and wife of a prominent burgher, tells how, in order to buy finery for herself, she became “one of the greatest brewers in the town of Lynn for three years or four, till she lost much money, for she had never been used thereto.”10 Margery later took up grinding grain in a horsemill, but had no better luck, her business failures helping her to see the light and turn pilgrim.

In England women made and sold charcoal. As “regratresses” they retailed products that had been purchased wholesale, joining the ranks of the fishmongers, poulterers, and butchers. Avarice, a character in Piers Plowman, recalls his wife as “Rose the Regrater…. /She hath holden huckstery all her lifetime.”11 Many women were innkeepers and restaurant proprietors, usually as widows inheriting from husbands. Women even plied such traditionally male trades as those of blacksmith and armorer: in a poem of François Villon, “La belle Héaulmière,” the beautiful helmetmaker grown old laments the loss of her beauty.

Another occupation that was already an accepted, if rare, female profession was schoolteaching; in 1408 a wealthy London grocer left twenty shillings to “E. Scolemaysteresse.”

Despite the prevalence of women among the crafts, it was long believed that the medieval guilds, the organizations, half trade union, half trade association, that dominated city working life, excluded women, but this has been shown to be false. Women were admitted to a large number of guilds as wives or widows of masters. Sometimes they belonged to guilds as femmes soles, even dominating some, such as the spinners’ guild of Paris. The famous 1292 Paris tax list of Etienne Boileau shows five exclusively female guilds, several others in which independent women enjoyed master status, and some eighty (of the 120-plus) with women members, presumed to be widows of former guild members. The basis of their admission was no mere courtesy to deceased guildsmen, but recognition of the obvious—a woman married to a craftsman necessarily learned the craft. Such widow guildswomen enjoyed full master’s privileges, including the decisive right to train apprentices. Should such a widow remarry, she retained her status provided her husband was also a member, but if he belonged to another craft, she lost her right to take apprentices.

In other French cities a similar situation prevailed. Statutes of Toulouse specifically mention admitting women to their guilds as weavers, finishers of cloth, candlemakers, wax merchants, and dealers in small-weight merchandise (avoir de poids, a regular classification at markets and fairs). In Arras the tailors’ guild admitted daughters as well as wives to master status at a reduced fee. In Poitiers the pastry cooks’ guild admitted women as masters, but qualified their status by decreeing that “Mistresses, when they are widows, can keep one or two workers, but they are permitted to carry only one single box of wafers through town.”12

The right to membership was disputed in some places. In Pontoise, near Paris, in 1263, the bakers sought to take the privilege away on the specious grounds that women were not strong enough to knead dough. The women appealed, and the Parlement of Paris overruled the bakers, further granting the women the unusual right to continue their profession even if they remarried outside it.

Although women were admitted to guilds in France, they were not always invited to the organizations’ social gatherings. In Arras the guild of cooks, roasters, pastry cooks, and caterers decreed that widows might enjoy the privileges of masters as long as they remained unmarried, “but they may not be present at the assemblies of the body, at the chefs-d’oeuvres [the meetings at which aspirants to the status of master presented their “masterpieces”], and at the receptions of masters.”13 At Poitiers in the thirteenth century, the guild of glovemakers admitted widows of masters to the craft, but specified that at the dinner given by the newly received master all the masters of Poitiers and their male children were guests, “but the wives, daughters, and servants of the glovemakers are expressly excluded.”14 On the other hand, the pastry cooks’ guild of Poitiers gave deceased mistresses the same six masses accorded the masters, in contrast to the valets, or journeymen, who got only two.

In the Florentine clothmaking industry, women were not admitted to the “greater guilds,” such as the Arte di Calimala (Wool Cloth Guild), dominated by wealthy trading companies, but had equal-to-male membership in the Linaiuoli (Linen-makers), on payment of the matriculation fee.

Women’s status in the English guilds was inferior to that on the Continent, but even in England a widow of a guild member remained in the guild and commonly conferred guild status on her second husband provided he worked at the craft. Widows could train apprentices; the Company of Soapmakers of Bristol lists in its records such notices as: “The Widdowe Dies took toprentice Michaell pope the Son of Richarde pope of Bristeltowe for the terme of VII yeares begininge the IIII of October 1593 and to serve a covenante yeare after,” and “We Reseved into the fellowship of Sopmaken and changleng [candlemaking] Richard Lemewell for that he sarved his Apprentisshipe with Alice Lemwell wedow to sopmaken and changlyng…. “15

The charter of the Drapers of Shrewsbury also speaks of both “brothers” and “sisters,” with women listed as wives of brethren, widows, and independent tradeswomen. The Tailors of Exeter permitted a widow to have as many workers as she wished as long as she paid her taxes. The Leather Dyers assigned three members and their wives as sworn overseers of the guild ordinances.

Guilds provided masses, tapers, and burial for women as for men, and in some cases through their eleemosynary auxiliaries, the “brotherhoods,” even furnished dowries for poor girls. The Guild of Tailors of Lincoln decreed that “if a brother or sister dies outside the city” the guild “shall do for his soul what would have been done if he had died in his own parish.”16

The London parish guilds, organizations that cut across craft lines to embrace the most affluent tradesmen of the parish, admitted women freely. One of the largest and richest, that of Holy Trinity, based at the church of St. Botolph’s Aldersgate, listed 274 women members in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, along with 530 men. Most were wives of craftsmen joining with their husbands, but there were also women who entered alone: a marbler’s wife, a huckster, and Juliana Ful of Love, occupation not designated.

Nevertheless, there was discrimination. Many guilds enacted regulations like that of the London Girdlers, who in 1344 ruled that members could not employ any women except their wives and daughters, or that of the Fullers of Lincoln: “None of the craft shall work in the trough; and none shall work at thewooden bar with a woman, unless with the wife of a master or her handmaid.”17

The problem was evidently the practice, widespread in city as in countryside, of paying women less for the same work. Documents of a later date attest to cheating that was doubtless prevalent in the earlier centuries—passing off daughters-in-law or nieces or even unrelated “wenches” as daughters, and hiring maids ostensibly for household duties and putting them to work at the distaff, wheel, or loom at lower wages than men. Another source of discrimination with echoes in a later age was the prohibition of the usual succession to mastery of a widow when the guild was one of those required to perform town military service or guard duty. Discrimination in pay and status forced many women to eke out their income by prostitution or thievery—women silk workers in Paris were threatened with the pillory for abstracting raw silk entrusted to them, and were further accused of luring scholars of the Latin Quarter into street recesses where they could be separated from the satchel-purses they wore at their belts.

Domestic servants., mostly single women, were the worst-paid women workers, if not in every case the worst off, toiling mainly or even entirely for their keep. After nine years’ service in the household of Walter Rawlys, Edith Nyman and her husband John claimed only 4 pounds 16 shillings in wages, making it appear that fourteenth-century free servants did little better than the slaves who were imported at that time as a result of the Black Death. Other evidence from England suggests a pound a year as typical servants’ pay. However, masters and mistresses often bequeathed legacies to servants, just as they often bequeathed freedom to slaves. London records include bequests of a hall and two shops; in another case land and houses; in still another an annuity of 9 pence a week, in a fourth, 20 marks and the next vacancy in the testator’s almshouse; and from poorer mastersand mistresses such sums as 40 shillings, or even “12 d. and one of my old gowns to make hir a kirtell.”18

At the opposite end of the spectrum from women servants were a tiny but significant number of city working women who profited as merchants. Most worked with and succeeded their husbands in a lucrative trade. In the fourteenth century, Alice, the wife of Thomas de Cantebrugge of London, dealt in armor on a scale that permitted her to be robbed of merchandise worth two hundred pounds. In 1304 two women wool merchants, Aleyse Darcy and Thomasin Guydichon, sold the Earl of Lincoln “one piece of cloth, embroidered with divers works in gold and silk… eight ells [thirty feet] in length, and six ells [twenty-four feet] in breadth,”19 for the huge sum of three hundred marks. A male colleague who acted for a woman merchant, Elizabeth Kirkeby, in a transaction in Seville, Spain, sued her for no less than four thousand pounds. Margery Russell, a fourteenth-century merchant’s widow of Coventry, also got into the legal records through commercial activity with Spain. Robbed by Spanish pirates of merchandise reputedly worth eight hundred pounds, she sought and obtained “letters of marque,” royal documents licensing her to seize as compensation Spanish-owned merchandise in English ports. Acting for all the world like a male businessman in similar case, she seized more than her due, provoking a counter-protest from the Spaniards. Wealthy and independent women such as these must have been among the four percent of London’s taxpayers in 1319 who were women living alone, most of them supporting themselves by practicing a trade.

Many other businesswomen have been identified in the later Middle Ages as dealing in large transactions. An outstanding example is Barbara Baesinger Fugger, daughter of a master of the mint in Augsburg, Germany, who after bearing eleven children found herself in 1469 a widow with no sons old enough to assume direction of her late husband’s textiles-and-other-thingsemporium. Barbara was equal to the challenge in business ability as well as in character, keeping the shop going and even expanding it while training sons Ulrich and George in management. A younger son, Jacob, she sent off to Rome to study for the priesthood, but when deaths of other children caused Ulrich and George to ask for Jacob’s help, Barbara canceled his clerical career, and thereby introduced to the commercial stage the greatest businessman of the Middle Ages, “Jacob the Rich” Fugger, whose loans to prelates and financing of the sale of benefices and indulgences played no small role in bringing on the Protestant Reformation.

The rising affluence of the high Middle Ages, most visible in the growth and prosperity of the cities, brought improvement in condition and status to a great number of city women. By comparison with later times, their situation remained hard and hazardous, but what is most striking to the modern eye is the extent of medieval women’s direct participation in production and distribution. In the last quarter of the twentieth century, in the most advanced countries, the economic contribution of city women remains less significant.