Underneath the tree canopy comes the understorey, which provides cover for larger animals, such as deer and foxes, as well as smaller creatures, such as woodland birds and, of course, small mammals. The understorey is formed by smaller woody plants and it varies in density and abundance, depending on just how much light gets down from above.

If your woodland is a light and breezy place, then more of the woody plants, like hazel, cherry and hawthorn, will thrive. But if your woodland is a super dark and dense conifer plantation, you can expect to move freely without getting your clothes snagged on brambles or thickets of thorn.

The advantage of the understorey to the naturalist is that because of the relatively short height of the understorey vegetation, the life that lives in it isn’t so far away. So being able to see what goes on is much easier than developing neck ache looking into the very tops of the canopy.

In the spring, it is the understorey that provides a home for the best singers in the dawn chorus. Here birds can claim territories and not have to worry too much about being seen by predators. If they do sing from a perch, it is only a short hop down into thick cover. This, of course, makes seeing anything that lives here a little frustrating, but with lots of patience and by moving around quietly, the understorey will eventually yield its secrets.

A good place to look for a nest is in the fork of a tree.

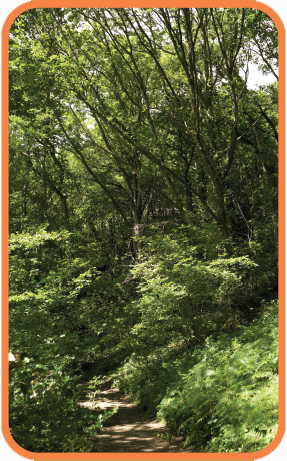

Here you can see clearly the understorey. But be aware that it isn’t always quite as obvious as in this picture.

The nightingale is a bird that spends almost all of its life skulking around in the dense scrub. Hence it is rarely seen but often heard.

A famous fluffy – the dormouse is a mammal that depends on just the right density of understorey trees and shrubs so that it can move around the woodland easily without coming down to the ground.

If you are a little impatient for spring and the winter has felt like a long one, this is how you can speed up spring and watch an amazing transformation at the same time.

Towards the end of winter take a short walk along a hedgerow and collect a few of the tips of living branches of some of the species of tree and shrub you find. Species with obvious buds, such as sycamore, ash and horse chestnut, are the best and most spectacular. When you get home place your finds in a jam jar of water and put them on a bright, warm window sill.

Here you can see a whitebeam, ash and silver birch. When looking at your buds, ask yourself are they tiny and round or long and sharp? Is the twig narrow and slender or quite thick? Are there a cluster of buds at the shoot tip or do they come out at the sides? What colour are they? Are they sticky or hairy?

Fab facts

* Trees in the understorey burst into leaf earlier than those in the canopy as the sap doesn’t have as far to travel. Logical really.

* Look closely at a twig and you will notice small details. Little bumps on the surface are pores known as lenticels. These let gasses in and out of the growing tissues.

* You may also notice small scars where last year’s leaves fell off. Look closer still and you may see lots of tiny holes in the surface of these. These are the disconnected ends of the departed leaves’ plumbing.

You do not have to wait until spring to see the magic of bright, brand new leaves. Just follow the tips in the box below.

Take it further

* Keep a close eye on your buds. Each one contains one of the best wrapped surprises in nature. Inside is a miniature crumpled collection of leaves and even a stem; some will also contain flowers.

* Just take the buds of horse chestnut or buck-eye. They are covered in a sticky, leathery, protective coating designed to deter those creatures that may want to open these parcels before their time.

* But as your buds swell, you will be able to watch them split and the scales separate. Eventually, the bud is levered out of the way and drops off, leaving a bud scar. This upheaval is caused by the pressure of the swelling, soft green new growth within.

* The leaves then continue to unfurl. Starting off like a crumpled green umbrella they soon expand to their final size. As they do so, the light yellowy green colour matures and darkens as the chlorophyll inside the leaves kicks into action and the process of photosynthesis gets under way.

* With some species, especially those of the willow family, your twigs may end up sprouting roots. Why not keep these? Grow them on as bonsai or plant them out somewhere?

What birds say to one another when they sing is along the lines of ‘Stay off my patch’, ‘I’m the boss here’ and ‘Come over here baby and breed with me!’ Mostly what we think of as cheery, happy music, to birds is really a war of the whistles. They are competing with each other and claiming their little slice of the world.

In the spring, when the breeding season gets under way, these territorial songs are particularly loud and obvious. This is especially the case first thing in the morning, when their singing is called the ‘dawn chorus’.

People often ask me how they can get to know the calls of all these different kinds of birds. My answer is to get out there and start looking and listening. Sure, various identification CDs will help, but there is no better way to get birds and their songs committed to memory than to actually see them singing. Once you have got familiar with the basic songs, test yourself. If you hear a bird singing, make a bold decision and then go looking to see if you were right.

Another way to get to know your local birds and also to get a better understanding of their lives, is to make a bird journal and map – see opposite.

The robin is a very territorial bird.

Take my advice

* The difficulty of learning bird song is sometimes down to the fact that many different species will insist on all singing at the same time! Is that a greenfinch over there? Could that be a starling? And then a blackbird starts up at the same time as a song thrush and really confuses and distracts your mind and your ears!

* The best bet is to start early in the year, because in that way you get familiar with the resident birds, the ones that have spent all winter with you. Then by the time all those exotic little brown jobs – the warblers – start to return from warmer climes, you will be ready for them. You will notice the new songs and because you have already got the others sorted out, you can concentrate on the newcomers.

* Do not worry, even the most experienced bird watcher has to relearn some of the songs every year.

YOU WILL NEED

> paper

> pencil

> coloured crayons

> binoculars

1 To start with, draw a map of your wood. Then, early on in the year, just as the common resident birds start to call, get up early and look for them.

2 Male birds that are defending a territory will often sing from regular spots, called song perches. This could be the top of a tree or even a telegraph wire. All you have to do is identify it and mark on your map where you saw your bird singing. Over time you will find the perches of many birds in your wood.

3 Watch when they fly off and mark the direction and where they stopped on your map. Assuming your bird keeps to its territory, you will soon get a feel for what this is by his movements within it.

Take it further

* Look out for other birds of the same species. Other singing males nearby will be holding their own territories and you may be able to work out the boundaries if you watch and plot their movements on the map using a different colour. If you can identify the female of a species, make notes of their movements too.

* Keep this up for a few weeks and you will soon have a great journal of bird life in and around your wood. Keep watching through the year and you may be able to work out where the birds are nesting, how many chicks they bring off the nest and whether they have a second brood or not.

It’s always a pleasure to interact with wild life. Whether it’s a pleasure for the wildlife is more doubtful. But as long as we don’t overdo it, there is a lot that can be better understood by us trying.

Impersonating the calls of birds is a form of mimicry and a way to get to know bird song really well. With some species, it is possible to get the attention of the wild creatures themselves. That still leaves those of us that are not very good at mimicry in the dark, but fortunately there are a few bird songs that even those of us who are tone deaf and far from pitch perfect can master. These are birds that can be ‘called’ by most of us.

Take my advice

While this is all good fun and a great educational experience, if it works, it is all the more tempting to keep calling the birds. But this is where a bit of respect needs to be applied. These animals are trying to get on with a life that is difficult enough without wasting loads of energy checking up on an apparent ‘intruder’ in their patch, which is what you will sound like if you are doing it right! So once you have got the reaction you were looking for, it’s only fair to leave the birds alone to get on with important stuff.

To attract a woodpecker, all you have to do is pretend to be another bird, which is as easy as finding a stick and whacking it against a good-sounding branch or tree trunk. Watch and wait and the local territory owner will come and check you out. If you hide yourself, you can even get it edging its way down the same tree you are hammering on.

Nick’s tricks

* In Europe, spring time is classically heralded by the distinctive two-toned anthem of a bird named after its noise – the cuckoo. Once you’ve mastered the art of this sound and you are out and about and you hear a cuckoo calling, simply call back. If the bird seems to have reacted and starts getting closer, hide and keep repeating. With any luck, you will get closer to a cuckoo than is usually possible in any other way. Oh, incidentally, make sure nobody sees you doing this or they really will think you have gone cuckoo!

* The other bird that is relatively easy to get a reaction out of is the tawny owl. It is best carried out at the time of year when the birds are calling themselves, usually when they are setting up territories in preparation for the breeding season. For the tawny owl in Europe this is early winter and during this time they are really sensitive, even to intruders that do not sound quite right. The call takes a little practice, but once you can make the low hooting noise, it is just a case of going out after dark with a torch and imitating the call timing and pitch of the wild birds. Hopefully you will get an owl coming so close to investigate that you will even be able to get it in your torch beam.

1 Having studied a cuckoo’s sound (see my trick, left), get a feel for it from the back of your throat and then repeat through cupped hands the phrase ‘ow-ooo’. The first sound has a sharp and abrupt end while the second has a sharp beginning. You have to almost shout this out as it needs to be heard over a great distance.

2 The tawny owl’s call is best made by blowing through your upright thumbs, into cupped hands.

During spring and summer, the woodlands and hedgerows are covered in leaves and birds carry out their daily lives more or less hidden from view. The whereabouts of birds and mammals are only given away by their occasional squeaks as young birds get stuffed with food, or a rustle as a squirrel leaps from branch to branch somewhere overhead in the canopy.

However, in the autumn when the trees lose their leaves, all this changes, and in woods and hedgerows you will be able to see dense bundles of twigs and vegetation where birds built their nests. You may be able to find out where those birds you saw in the summer were living, or the nest might give you a clue about which birds live in that habitat.

At first, one nest may look very much like the next: just a tangle of sticks, straw and mud. But with a little experience, a touch of guesswork and some persistence, you will be able to see that different birds construct different-looking nests.

>Magpies make large, loose, domed, stick nests.

>Rooks construct nests close together as a community in the treetops.

>Crows build solitary nests.

If you’re really observant, in summer you can look out for the bored out nest holes created by woodpeckers. Different species create holes of different size, on trees of different ages, or even in different parts of the tree.

Take my advice

It is very important that you never disturb a bird’s habitat, so always treat nests with respect and remember that it’s best not to remove them from the place where you find them.

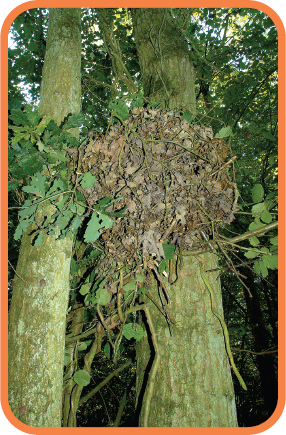

When looking for nests, it’s not just the homes of birds that you are likely to come across. While scanning the tops of a woodland, you may well come across the summer drey of a grey squirrel, but the chances are that you wouldn’t know you were looking at one. They resemble a hollowed-out crow’s nest built high out on the branches. Much more distinctive is the dense winter drey that is also used as a nursery. These are often much larger and constructed with leafy twigs and lined with mosses and grass. They are also built close to the trunk where they are less prone to the buffeting of winter gales.

Take it further

* Once a nest has been used for one season it is rarely lived in again – well, at least not by creatures with feathers! So if you know of an empty nest, don’t move it but take a good look inside. You might be surprised at the colony of little squatters that are present. The creatures that like to live in the leaf litter, such as woodlice, spiders and multipedes, will think they have stumbled across a particularly smart equivalent of their usual habitat.

* You may also find various parasites of the birds that originally owned the nest, such as fleas, mites and lice.

* Other creatures you could see include the moths that can get into your clothes or the beetles that can get into the carpet. In nature, these animals have an important role to play: they recycle keratin, the stuff feathers and fur are made of, and of course, there is plenty of that in most nests.

You can look for the drey of the grey squirrel at any time of the year. They are, however, easier to see once all the leaves have fallen off in the winter.

Birds’ nests are real works of art, and different species construct their nests in various ways, using specific materials for the job. Song thrushes are unique among British birds in having a hard lining of mud to their nests, while blackbirds actually line the nest with fine grasses, even though they use mud in the construction. Some birds create very delicate constructions, while others look like a more messy pile of twigs. In Japan, some city-dwelling crows have even been known to make their nests from coathangers!

Why not have a go at making your own nest? You will quickly see just what clever architects these birds are.

YOU WILL NEED

> twigs and small sticks

> mud

> things to line your nest, such as hair of different types, grass and hay, feathers, moss and leaves

A bird’s nest is a masterpiece of design, whatever the species.

1 Set aside a good space to work and gather your collection of materials.

2 Try to make a basic frame for your nest by using some of the sticks.

3 Add some mud to the frame to see if this helps stick everything together.

4 Gradually build up the nest with the softer materials, like hair and grass, to form a strong, solid structure capable of protecting fragile eggs and baby birds. Find a good location in a nearby hedge or tree. A bird may want to use your materials, or insects may decide they want to adopt your nest as their home!

Take it further

* Look at different hair. How does yours differ from a horse’s or badger’s?

* Different trees and shrubs produce very different sticks. Some are thinner and easier to bend than others – try them out and see what happens.

* To make this even more challenging, find out how a particular species constructs its nest and try to copy it in style, using only the materials it uses. Can you do such a neat job?

Hedgerows were originally planted to mark out boundaries and to keep livestock from wandering off. But if you look closely, you will see that these living walls are a lot more than just a bunch of tangled up, closely planted trees. They are like mini elongated woodlands, often becoming home for plants and animals that are more usually associated with larger clusters of trees.

Choose a bit of hedgerow near you and get to know it. Many hedges have been part of the landscape for hundreds if not thousands of years, though sadly, many are being torn up to make way for large-scale intensive farming.

There are ways you can get an idea of how old your hedge is by just doing a little bit of investigative work. Old maps and plans in your local library may give you some clues. The hedge may also be associated with ancient features of the landscape, such as trackways or Roman roads in Britain, which can give you a further idea that you may be dealing with a very old hedge.

Nick’s trick

* Honeysuckle is a somewhat secretive climber that scales trunks, leaning on other more substantial woody plants to gain support and sometimes a lift up to the light. Its bark peels off in thin papery strips and it is this natural parchment that many mammals find so useful, particularly dormice, who use it to line their nests. In southern British open woodlands, this plant also provides food to a striking woodland butterfly, the white admiral. But when it flowers in sheltered woodland glades in the summer, it fills the air with a sweet and heavy aroma.

* Ever wondered about the name, honeysuckle? Well, next time you see a plant in flower, pluck one of the tube-like flower stalks (those that are just about to open are best), making sure you pick it from the base. Now bite into the flower base just enough to nick off the end, and suck. Your tongue will be touched by the sweet nectar usually reserved for moths at nightime. Yum!

Looking at the different species of plant found within a hedge can also give you some clues about how old it is. This is all thanks to Mr Max Hooper, who was the first person to notice that there is an association between the number of ‘woody’ species and other indicator plants, such as bluebells and wild garlic, and the age of a hedge. This is now known as Hooper’s rule and is explained in Step 3, below.

The reason this works is that the older the hedge is, the more time there has been for other species to colonize it. But this does not apply to those hedges that have been newly planted and it works in some areas better than others. Having said that, getting to know your hedges and what they are made of is definitely a worthwhile exercise.

YOU WILL NEED

> tape measure

> pencil

> paper

1 Choose your hedge and mark out a 30m section of it.

2 Count the number of different species of tree and shrub found along its length. It helps to understand what species are what, so choose a time of the year when there are leaves present just to make things a little easier – and use a field guide too. Do this a number of times on other 30m sections of the hedge and note down your finds each time.

3 Take an average by adding up the all the scores and dividing by the number of 30m sections surveyed. And now for Hooper’s rule: multiply this number by 100 and this will give you your estimated hedgerow age. So if you count five species of woody plant, your hedge is probably around 500 years old!

I know watching seeds sounds like an activity that is about as exciting as watching paint dry and grass grow, but bear with me, there is a point to all this – and that is, ANTS. These fine little chaps are very good at clearing up the place, but they are also gardeners. Remember those slow-growing, slow to colonize woodland flowers such as bluebells and violets (see page 11)? Well, both of these plants rely on the valuable courier services of ants to shift their seeds about on the woodland floor.

Fab facts

Have a good look around the base of a violet and you may find some small little flower heads, which are there as a backup. They contain seeds that do not need insects to pollinate or carry them. So just in case the insects do not do their job properly, there will still be violets next year. This is also the reason they can exist in dense clumps.

1 In the spring, collect some ripe seeds of various flowers. I find those little plastic film canisters are really handy for this as they are dark and airtight. If you don’t have any, ask at your local photo-developing shop.

2 Then find the ants – it shouldn’t be too hard, they are never very far away. If you find a colony or a trail that are foraging, tip out your seeds in a pile and watch what happens. Do the ants show an interest in your seeds?

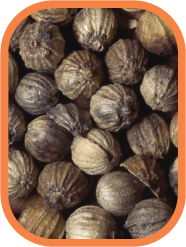

3 What you may see is that some seeds have a ‘handle’ on them, which contain substances such as oils and proteins, which the ants quite fancy. So they pick up the whole thing and carry it off, providing a very valuable delivery service for the otherwise slow-to-disperse plant. Back at the nest, the handle is chewed off and the very hard seed discarded.

Take it further

Try out other seeds on your ants. Does the type of seed make a difference? Do different types of ant prefer one seed to another?