A tree on its own is never a tree on its own. Trees act like a life magnet. You can have a plain bare patch of grass with nothing much in the way of wild life hanging around. But stick a tree in the middle of it and it’s a whole different story. Birds will perch in it and may nest there, insects will find it attractive and nibble or even breed in it. As the tree gets bigger, it creates more living space for even more life.

Making an inventory of a tree near you is always a fun thing to do, and would be a great idea for a personal project or something you can do at school. Try to count as many living things as you can, from the microscopic algae that give the cracks in the bark a greenish tinge, to the birds and mammals that visit. You will be very surprised at what you find.

But just imagine what happens when you stick a collection of these incredible trees together! The effect is magnified, which is why woodlands are such amazing places to explore and why some people make such a fuss when they get removed.

This chapter is about the trees themselves – what they are, how they live and grow. Get to know the trees and you will begin to understand and love the heart of the wood itself.

Fab facts

Here are some BIG numbers for the big European oak:

* 40 hectares of woodland can support 300–400 birds.

* 30 different types of lichen have been found on the bark of these trees.

* 200 species of moth live on the leaves.

* 45 true bugs suck its juices and stalk other prey among its branches.

* 65 mosses and liverworts can be found on the bark.

* 40 species of galls have been found on oak trees.

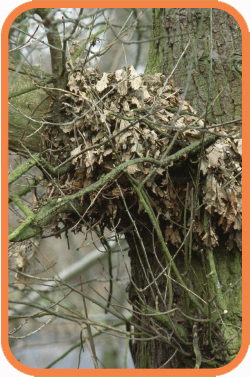

An oak apple or gall may end up on the woodland floor, but while it’s alive, it grows much further up a tree, near the tree canopy.

A grey squirrel’s drey, neatly perched high in the canopy.

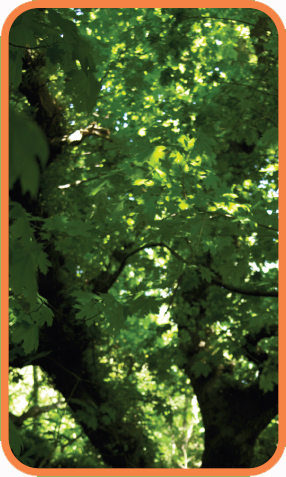

The dappled sunshine emerging through the tree canopy is always a cheering sight.

Many woodlands have been a feature of our landscape for a long time while others have been cleared and have either been re-colonized or re-planted. While all woodlands offer shelter and food for certain creatures, those that have been around for longer tend to have a greater number of species. This variety of species is called biodiversity.

In the spring, investigate your local woodland. Is it ablaze with colour, as a carpet of plants explode into flower and leaf? There is only a brief window of warmth and light in a wood before the leafy canopy closes over and returns most of the wood floor into the dappled half light. This is why so many plants in the understorey have broad leaves (see also opposite).

We humans have real trouble thinking outside of our own life expectancy. We tend to think that we have had a good innings if we get to 80 years old, but most trees at 80 have barely got going. Living at a slower speed than us is part of their fascination. As long-lived plants, they have their own stories to tell. They are like living history lessons, telling us about their own lives and the conditions to which they were exposed as they grew.

Get to know some of the truly old trees in your area. Work out their age (see pages 18–19 and the Take it further box, opposite) and learn about their history; perhaps relate it to famous historical events in human history, such as wars and invasions. You will soon get a sense of what events these trees may have stood through. This is the first step to tree appreciation and helps you to enjoy them fully. You can also maybe help a little by planting a few of your own (see pages 24–5).

Look closely at many spring-flowering plants. They have large, broad leaves designed to steal as much of the sparse light that falls on them as possible. Many also grow in large and dense mats, a sign that they reproduce and spread mainly by bulb splitting and underground runners, rather than by seeding. The fact that they spread like this means they tend to be specialized at surviving in woodlands but are next to useless at spreading to new locations. As a result, they take many years to colonize a woodland.

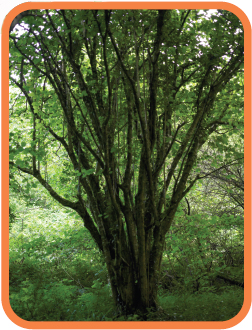

Woods were once used as a crop and their products were used in day-to-day life. Look for multi-trunked trees that seem to grow from a thick and gnarly old base. These may well have been coppiced at some time. This is the process of harvesting the straight poles that sprout from a cut stump. Some of these would be used for building poles or for making hurdles or fences, while others would be burnt to produce charcoal for smithies and home fires. Today, coppicing still goes on in some woods.

Take it further

* Other clues to the age and use of a woodland or hedgerow can be found by looking for tell-tale traces of how man has managed them.

* Old woods tend to have uneven and curved boundaries while new ones are usually straighter.

* Plants are another great way to tell if a woodland is ancient. Look for:

Bluebell

Wood anemone

Pignut

Wild garlic

Wood sorrel

Dog’s mercury

Cow wheat

Primrose

Wild daffodil

Early dog violet

Starting to identify trees can be a little daunting. Some of them are easier to tell apart. For example, conifers have cones and needles and they keep their leaves all year round. Deciduous trees have big flat leaves that turn brown, yellow and red and fall off in the winter. But learning about trees in more depth can be difficult. To help, make your own tree log. This is an excellent way to collect as much information as possible about the trees in your area, and you can start at pretty much any time of the year.

The first characteristic to look for in your tree is the shape of the leaves. Each species has its own very distinctive leaf pattern. Most are instantly recognizable from this quality alone, although there are a few that you may find a little tricky, such as hornbeam and elm, and a few of the exotic species introduced from other countries, but you will soon get the hang of the main native species.

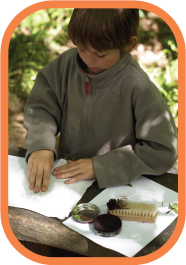

Start by collecting a selection of leaves, either from the ground or directly from the tree itself. Once you have these leaves back at home there are several ways you can incorporate them into your log – start with the ideas opposite and more are given on the following pages. You can then move onto exploring the bark (see pages 16–17), seeing how old it is (pages 18–19) and drawing its profile (pages 20–21).

To make your tree log, use a scrap book or collect some loose pages or some clear plastic pockets. You can keep adding to your file as you find more information and evidence.

YOU WILL NEED

> leaves

> sticky tape

> watercolour paint

> paintbrush

> paper

> shoe-cleaning brush

> shoe polish

> blotting paper

1 Use your leaf like a stencil. Place it on paper and fix the stem with sticky tape.

2 Carefully paint over the leaf, just going over its edges. Let it dry.

3 Slowly lift the leaf and, hey presto!, you are left with a perfect outline of your leaf.

4 You can also use a stiff brush to apply some dark shoe polish to one side of your leaf. Dead leaves that have fallen from a tree work best for this approach as they are stronger and more rigid.

5 When it is well covered, turn the leaf over and press it firmly onto a plain sheet of paper to leave an imprint. Press some blotting or kitchen paper over this to sop up any oily residues.

If you have been sifting around in the bottom of a pond or ditch, you may occasionally stumble across a stunningly beautiful phenomenon – that of a leaf that has had all the soft parts nibbled away to leave a net-like web of veins. These veins are all that is left of the leaf’s plumbing. The tubes and pipes are what the sap of the plant flows through, carrying essential chemicals around the plant’s body.

There is a rather simple and fun way of recreating this effect to order. Not only are they a beautiful thing to have in your tree log but they can also be mass produced, painted and used in many creative ways, such as on a collage picture and to decorate cards.

Nick’s trick

* Pressing leaves is the same as pressing flowers. You can either use a professional flower press – a stacked sandwich of alternating cardboard and blotting paper between two boards with bolts in each corner – or you can use a heavy book or two to weight down the layers.

* The most important thing is to place your leaf between some absorbent material like blotting paper or kitchen towel. Sheets of plastic will also stop any plant sap from oozing out and ruining your book cover or pages.

* Change the blotting paper every other day and after a week or so your leaves will be preserved. I like to store mine in individual plastic envelopes with a label on the outside of each one saying what it is and where the trees were growing.

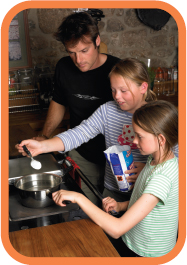

YOU WILL NEED

> leaves

> washing soda

> a pan of water

> a soft paint brush

1 Fill your pan with water and add about 2 dessert spoons of washing soda for every 500ml of water.

2 Place the pan on a gentle heat until it is simmering, then take the pan away from the heat and place your leaves in the solution.

3 Leave them submerged for a good 30 minutes, making sure all of the leaves are under the surface. Then gently wash the leaves with fresh water by placing the pan under a slowly running cold tap, letting the water flush out the soda mixture and soft debris.

4 You should now be left with beautiful transparent leaves. To remove the soft material surrounding the veins, place the leaves on a saucer and gently brush with an artist’s paintbrush. Leave to dry on some kitchen towel.

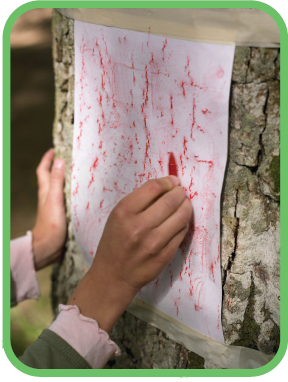

Another distinguishing feature of a tree, and one that remains even in the winter when most leaves would have dropped, is the texture of the bark. The quickest and easiest way to record this is to make a rubbing – see Nick’s trick, below. The other way of recording your tree requires a little more effort, but it produces a really smart, three-dimensional model of a section of tree trunk – and that is by making a cast of it (see opposite).

Hold the crayon or pastel on its side for the most effective technique. This really helps to bring out the textures underneath.

Nick’s trick

* Carefully tape a piece of paper to the trunk of the tree and then colour over it with a crayon or pencil (dark looks best on white paper, but white chalk on black paper is pretty stylish, too).

* In this way you record all those textures and patterns and soon you will start to recognize a combination of these features and the colours. I have a friend who is a blind naturalist and he can tell most species of tree by these very textures you will be recording with your rubbings.

YOU WILL NEED

> modelling clay

> strong cardboard box

> plaster of Paris

> water

> poster paints

> paintbrush

1 First find the tree you wish to make an impression of. Then knead and pummel your modelling clay so it is soft and free of air bubbles. This makes it much easier to work with and gives you a better impression at the end.

2 Firmly press the clay into the tree’s surface. Try to keep the clay at least 1.5cm thick and aim to keep the edges from tapering. If you are going to make many such casts for a collection, use standard dimensions at this point as it makes the casts easier to store and/or mount.

3 Peel away the clay and you will notice all the bark textures on it. You now have to get this home without damaging the mould, so this is where a stout box to transport the clay comes in handy.

4 Once back at base, place the mould with the textured surface uppermost. Then use more modelling clay to make a ridge at least 2.5cm higher than the mould. You can choose at this point whether to make a curved cast, like the profile of the tree, or a flat section.

5 Following the packet’s instructions, mix some plaster of Paris with water. Pour the plaster into the mould and leave to set for a few hours. Then carefully lift and peel away the modelling clay to leave your bark cast, ready for display.

6 If you like, you can paint your bark impression with poster paints so that it looks even more lifelike.

The most accurate way to tell the age of a tree is to look at a slice through its trunk and count the growth rings. The cells under the tree’s skin (the bark) produce new wood as the tree grows and each summer, more new cells are made when conditions are best for growth. Growth rings show each year’s new growth – one for each year of the tree’s life. In years of good growth, the rings will be wider.

Obviously getting to see these growth rings in a healthy tree is impossible without cutting it down and destroying the thing you are studying! But if you come across stumps that have been sawn through and the cut is a smooth one, you should be able to see how old it was when the tree was felled. This will give you an estimated age of any tree of the same species in the same area.

Some trees grow very slowly indeed, but others have many a growth spurt, such as the commercially grown pines, various cedars, spruce and fir, poplars, cricket-bat willow and other non-natives such as eucalyptus. Slower-growing trees include pine, yew, chestnut, lime and most smaller-growing trees.

Fab facts

* Trees grow from the outside in! The growth cells are all in the surface of the wood, under the bark. They lay down new wood as the tree trunk expands. The wood in the middle of an old tree is usually dead and when a branch falls off, it is this that sometimes gets hollowed out by fungus and birds.

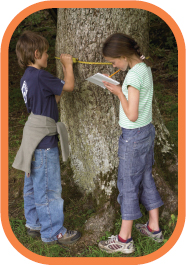

YOU WILL NEED

> a tape measure

> pencil

> paper

> calculator

1 Another way to estimate a tree’s age is by measuring the girth of the trunk about 1m up. Because large trees tend to grow at a predictable rate, their trunk gets thicker as they grow and on average, trees put on about 2.5cm a year.

2 So measure your tree’s girth in centimetres and divide it by 2.5. You will then have an approximate age for your tree. This is a very rough guess and growth rate does vary from species to species and from place to place.

Take it further

* Try to find a tree stump that shows the tree is, say, at least 100 years old and take a photograph of it.

* Either have the photograph enlarged or I enlarge a photocopy. If you have a digital camera, print out the image to whatever size you want. You can then mark important years on the trunk by counting back rings.

* Show the year 2000; the year you were born; when the Second World War started, and add anything else that is of interest to you and your family.

For any tree, you can create a profile of its shape and height. It is not too hard to figure out the circumference of a tree trunk, you just need to put a tape measure around it, as if you were measuring your own waist (see previous page). But height is a different matter, especially if you are dealing with a large, mature woodland tree. Fear not – it’s surprisingly easy (see opposite).

You can also measure and record the shape and size of the tree canopy by drawing the trunk on a piece of graph paper (say, 1cm on the paper equals 1m in real leaf). Pace out to the distances from the trunk to the edge of the canopy as you lookup. Repeat all around the tree. Add these distances to your plan on the graph paper.

The size and the shape of the tree can give you a good idea of the way it has grown and the condition it is in. For example, if it is leaning to one side, that might show the most usual wind direction.

Like all living things on Earth, trees need to reproduce, so the last addition to your log will be descriptions of when and how the tree ‘flowers’. Look for flowers and seeds and note how they grow. Do they dangle? Are they on short stems or on twigs or old branches? Collect and draw or photograph these for your tree log.

On a silver birch, the seeds hang from the branches on long stems.

Take my advice

Part of your tree profiling could be to get to know the animals and other plants that can be found living in or around your tree.

YOU WILL NEED

> a friend

> pencil

> paper

> tape measure

1 Standing some distance away from your chosen tree, hold the pencil up at arm’s length. Move backwards and forwards until the pencil’s height is the same as that of the tree.

2 Rotate the pencil through 90 degrees, keeping the base of the pencil in line with the base of the tree. Ask your friend to walk away from the tree to the point that corresponds with the tip of your pencil.

3 Ask your friend to mark this spot and then measure the distance between the tree trunk and your friend.

4 On a piece of paper, note down the distance. It is very important as it equals the height of the tree. Magic!

You will now have a fantastic record of all your tree observations.

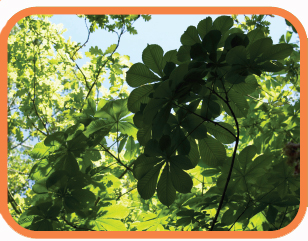

Here is a project that will give you a great deal of satisfaction. Just by whittling a piece of sycamore, it is possible to make something that whistles in a most enjoyable way. But first you have to identify a sycamore or maple. These trees are very common in deciduous woods and have large flat leaves with several points on them. Think Canadian flag and that is a maple leaf (see left and page 29). Other easy-to-identify features are the seeds or keys, which are the famous paired winged seeds that work a little like a helicopter (see page 52).

YOU WILL NEED

> a sycamore tree

> penknife or craft knife

1 Get an adult to help you cut a 6cm length of sycamore branch that is about the same diameter as your finger. It is easier to make if you let the twig dry out a little for a couple of days.

2 About 2.5cm down the twig, use your knife to score right around the middle.

3 About 1cm down the twig cut a small slot in the bark, making sure you have cut right through the smooth bark and scored the wood below.

4 Now for the tricky bit – tap and loosen the bark at the top of the whistle and slip the bark off in one piece.

5 Where you scored through to the wood below, cut out a thin slither of wood. Don’t make it too deep.

6 Slide the bark back over the twig, lining up the hole in the bark with the hole in the wood. Now blow!

Growing your own tree is a great way to learn all about seeds, trees and the different ways they grow, and at the end of it you will have a small woodland developing right before your eyes (see opposite)! You can then either plant the seedlings or give them away as presents to friends and relatives. First, though, you will need to collect your seeds. Different trees have different kinds of seeds, but the easiest are those that simply drop off the tree as they do not need any special conditions. Examples are oaks and their acorns, hazels and their nuts, and others like ash and field maple, which have winged seeds called ‘keys’.

Most trees produce their seeds at the end of the year, so set out on an autumn day and try to beat the squirrels, especially to the hazelnuts, which they collect off the tree as they start to go brown.

Seeds that are inside a berry have to be treated differently because they are designed to be attractive to birds who swallow the berry, pip and all. They then pass through the bird’s gut and land in the bird’s droppings later. This helps the seeds spread away from the parent plant and also gives the seed its own little dollop of fertilizer to get it off to a good start. Species such as holly and rowan are good examples of trees that use this technique. To get these to grow you need to put the poor little seeds through some rough treatment to replicate the guts of a bird – see Step 5.

Fab facts

* A mature oak tree produces around 90,000 acorns a year, but only one of these will ever get a chance to make it to being a tree!

* Keep an eye open for wood pigeons as they are great fans of the acorn. Each bird can carry up to 70 in its crop at one time and consume over 120 in a day.

* A little acorn that is developing during the summer is known as a nubbin – what a great word!

YOU WILL NEED

> small flower pots

> small stones

> peat-free potting compost

> seeds

> labels

1 Place some stones or broken bits of tile in the bottom of each pot to help it drain, then fill the rest with potting compost.

2 Make a hole in the centre of the compost, about half a finger’s depth.

3 Place a seed or nut into the hole and cover with compost. Label each pot so that you don’t forget which tree is in which container. Water the pots thoroughly.

4 Store the pots somewhere like a potting shed or garage over the winter, where they will stay cool. This will stimulate them to germinate in the spring. Be aware that mice will not only visit their own stores for the winter but will happily eat any other seeds they stumble upon with their keen sense of smell. So make sure your seeds do not get nobbled by the nut nickers! Keep your soil damp, but not too wet.

5 If you collect some berries, mash them up, then wash off the seeds and let them dry out. Put the seeds in a pot with a mixture of sand and peat-free compost and leave out for the winter. Come the spring, plant the seeds in a seed tray. They will start to shoot and you can watch a ‘woodland’ spring up before your very eyes. Some trees, like oak, are quite slow growing, others are much faster. Re-pot them as they grow.