China’s Final Victory, 1943–5

By 1943 the Sino-Japanese War had been fought for six long years and both the Japanese and the Chinese were exhausted. War weariness amongst the Japanese in China had become a major problem with no end to the war in sight. The ever expected Nationalist collapse had never materialized and all Japan’s efforts to subdue the Chinese had failed. Some Chinese had collaborated with the Japanese but they were despised by the vast majority of the population. The Japanese population’s enthusiasm for the war had also faded as more and more of their sons’ ashes were returned home for burial. However, the Japanese were still committed to their occupation of China and over 1,000,000 men were still serving there. With no hope of further reinforcements for China, especially in terms of weapons and equipment, the Japanese Imperial army could not defeat the Chinese. The Japanese were unable to defeat Nationalist China before they had commitments to their Pacific War, from December 1941. Now with Allied aid supporting China, even if in limited quantities, the Chinese were getting stronger as the Japanese were weakening. A stalemate now existed in China and the Japanese Imperial army no longer had the will to try and defeat the Chinese. At the same time, the Nationalist and Communist forces could not hope in the short term to defeat such large Japanese forces stationed in China. Japanese tactics had also changed since 1941 with the emphasis now on holding onto what they had gained rather than trying to conquer more territory. When they went out on operations the main aim of the Japanese was to take food and other supplies from the population. As time went on, the Japanese Imperial army was less willing to confront Chinese forces, whether regular or guerrilla. At the same time, the average Chinese soldier had lost their inferiority complex towards the Japanese army and its soldiers.

Although the Chinese theatre was still important to the Japanese, the situation with the Allies was to take on more significance. Their struggles in the Pacific from 1942–5 and with the British in Burma from 1943–5 became more important. Much of their heavy equipment had, however, been transported to other theatres and in particular the Pacific Islands. Because of their weaknesses the Japanese Imperial army had now to concentrate on trying to control the guerrilla threat in China until 1945 (see Chapter 6).

In one final desperate effort to reverse their decline in China the Imperial army launched a large-scale offensive. In April 1944, the ‘Ichi-Go’, or ‘Number One’, offensive was begun and was to be one of Japan’s last major operations in China. Huge Japanese forces were marshalled for the offensive with 400,000 men, 1,500 artillery pieces and 800 tanks taken from all over China. Ichi-Go was divided into two separate operations with the first, ‘Ka-Go’, aimed at destroying all Nationalist forces still north of the Yangtze River. One of Ka-Go’s aims was to surround and destroy the Nationalist army that held part of the Peking–Wuhan railway. This objective was easily achieved, although the Japanese advance was limited by lack of supplies once they out reached their supply lines. A second phase, known as Operation ‘U-Go’, was to be launched once Ka-Go had got underway. The aim of U-Go was to knock out the airbases of the US 14th Air Force which were being used to bomb the Japanese mainland. After destroying these airbases the combined Japanese force was to advance into Szechwan province with the ultimate aim of capturing the wartime capital Chungking. Nationalist divisions facing the offensive were made up of poorly trained and armed conscripts who were soon demoralized and fell back in front of the advancing Japanese. U-Go was a great success and the US air bases fell in quick succession as the Nationalist forces retreated in confusion. On 8 August the city of Hengyang, to the east of the Chinese capital, fell to the Japanese and it seemed that an advance on Chungking was now inevitable. As the campaign in southern China dragged into November 1944, however, the Japanese began to run out of food and other supplies. Vital air cover was also lost when the Japanese had to send its fighters to Japan to defend their homeland. Over the next few months Ichi-Go ground to a halt and the Chinese finally began to make some successful counter-attacks. Chiang Kai-shek had been proved right when he said that ‘The Japanese will run out of blood before the Chinese will run out of ground’.

In April and May 1945 the Japanese launched what was to be their last offensive in China with the aim of capturing a US air base at Chihchiang. The Chihchiang Offensive was launched from territory recently taken during the Ichi-Go operation. Large Nationalist forces were stationed to halt the advance and after being reinforced to a strength of four divisions they threw back the Japanese. In early 1945 the Japanese Imperial High Command had already introduced plans to consolidate their positions in China. By withdrawing units from outlying garrisons in southern China they intended to concentrate them in central China in the region of Wuhan. Other formations would be gathered in the Canton region and in the Peking region, where they faced less opposition from guerrilla forces. As the Japanese tried to move their forces into these fastnesses they came under attack by Chinese guerrillas. In August a new threat had to be faced in Manchuria, which although not strictly involved in the Sino-Japanese War, was to influence its end greatly. The Soviet Union’s victory in Europe in April 1945 released huge numbers of troops to take part in a new offensive in Manchuria. Since the 1900s Japan had always feared an attack in the East by the Red Army but a neutrality pact signed between the Soviet Union and Japan in the 1930s had held. Now that Japan was on the verge of defeat, the Soviet Union decided to renege on this agreement and on 8 August they struck. With an overwhelming army of 1,500,000 men, 26,000 artillery pieces, 3,700 tanks and 500 combat aircraft, they launched a blitzkrieg offensive that swept the Kwangtung Army away. The Kwangtung Army was a substantial size on paper but out-of-date tanks, obsolete artillery and depleted units were the reality. Soviet claims of 84,000 Japanese dead and almost 600,000 prisoners taken were not disputed. Although not really part of the Sino-Japanese War, this was a devastating defeat for the Imperial army in East Asia.

However, the end in China was be dictated by events elsewhere and with Japan’s defeat in the Pacific and the dropping of atomic bombs in August 1945, the war was over. On 2 September all Japanese military forces in China officially surrendered to the victorious Chinese, both Nationalist and Communist. Most Japanese military and civilian personnel were repatriated quickly with a surprising lack of violence from the triumphant Chinese. Nationalist China’s victory was to prove illusionary as within a short time conflict was to break out with the Communists. After a brief interlude and attempts at mediation between Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Tse-tung, the civil war between the Chinese Nationalists and Communists was to resume in 1946.

Nationalist troops are moved up the Yangtze River in a flotilla of river junks during a Chinese offensive in 1943. Although the cliffs rising up from the river will provide some cover for troops on the move, they will still be vulnerable to Japanese air attack. After the disaster of the 1940 Nationalist offensives and with more precious equipment and manpower lost, any further operations had to limited ones. This did not stop the Chinese from launching small-scale attacks on the Japanese whenever they saw a weakness in their enemy.

During a Japanese offensive an infantry section moves across a street under fire while a shell from its artillery bursts in the distance in 1943. The Imperial army’s offensives by this stage in the war were usually aimed at specific objectives rather than capturing more territory. One of the main battles in this year was for the city of Changteh, which was fought over for a month-and-a-half in November and December. Many Japanese soldiers of the post-1941 period were not up to the standard of the first troops who had fought in China in 1937–41.

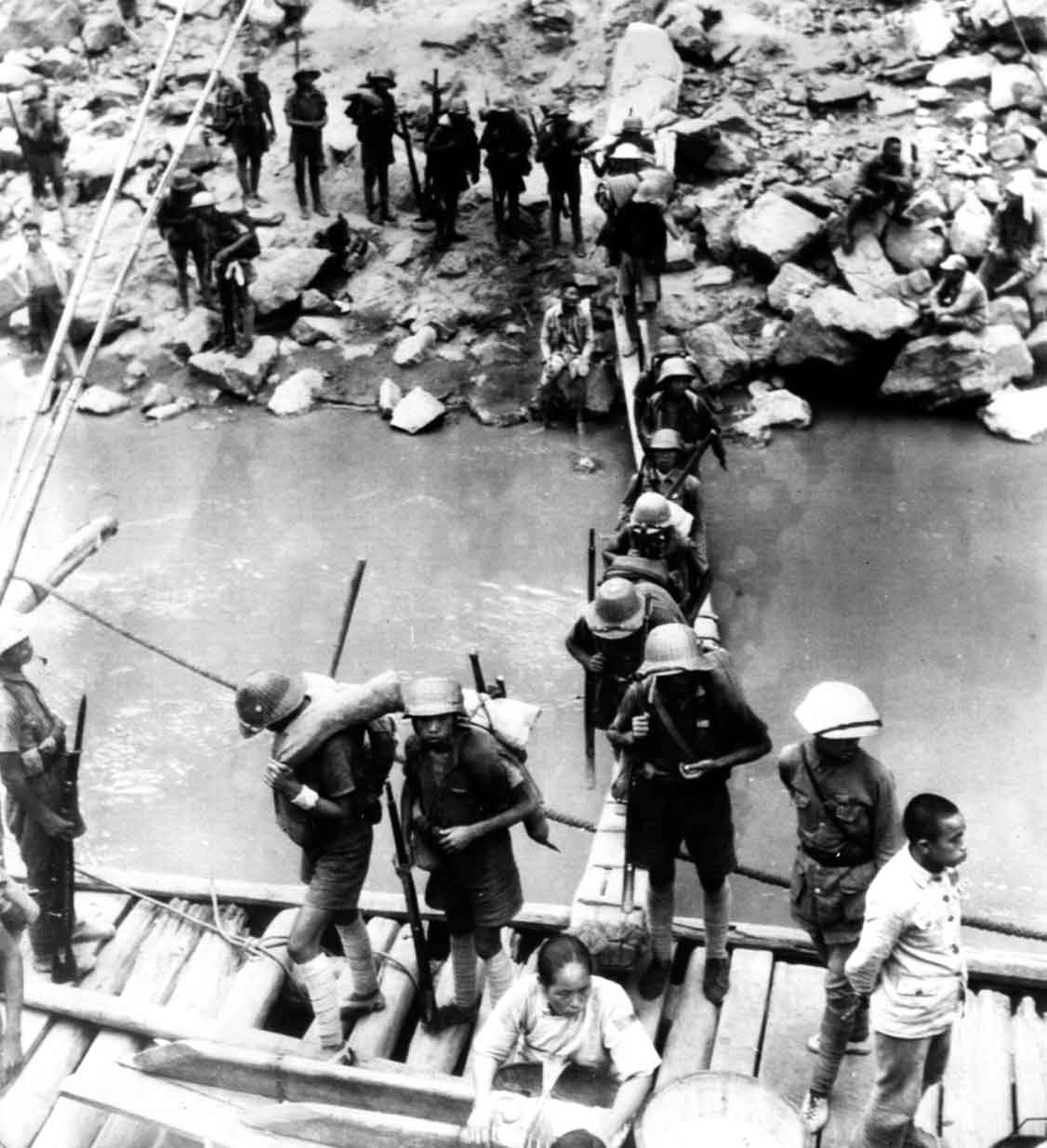

On the banks of the Yangtze River in May 1943 Nationalist troops wait patiently to board civilian junks to be moved to the front. Some of the troops are wearing bamboo versions of the M35 steel helmet which may from a distance look like the real thing. Obviously, this headgear would provide no protection for the soldier but at this stage of the war nothing else was available. Uniforms and equipment used by much of the Chinese army after 1941 had to made using local resources. Although the Allies were providing arms to the forces trained in India and western China, the majority of the army used rifles imported before 1939.

A Nationalist army machine-gunner aims his ZB-26 light machine gun from behind a wall reduced to rubble during the battle for Changteh in December 1943. He belongs to the 57th Division which fought bitterly with the Japanese for control of the city, with only a few hundred surviving the battle.

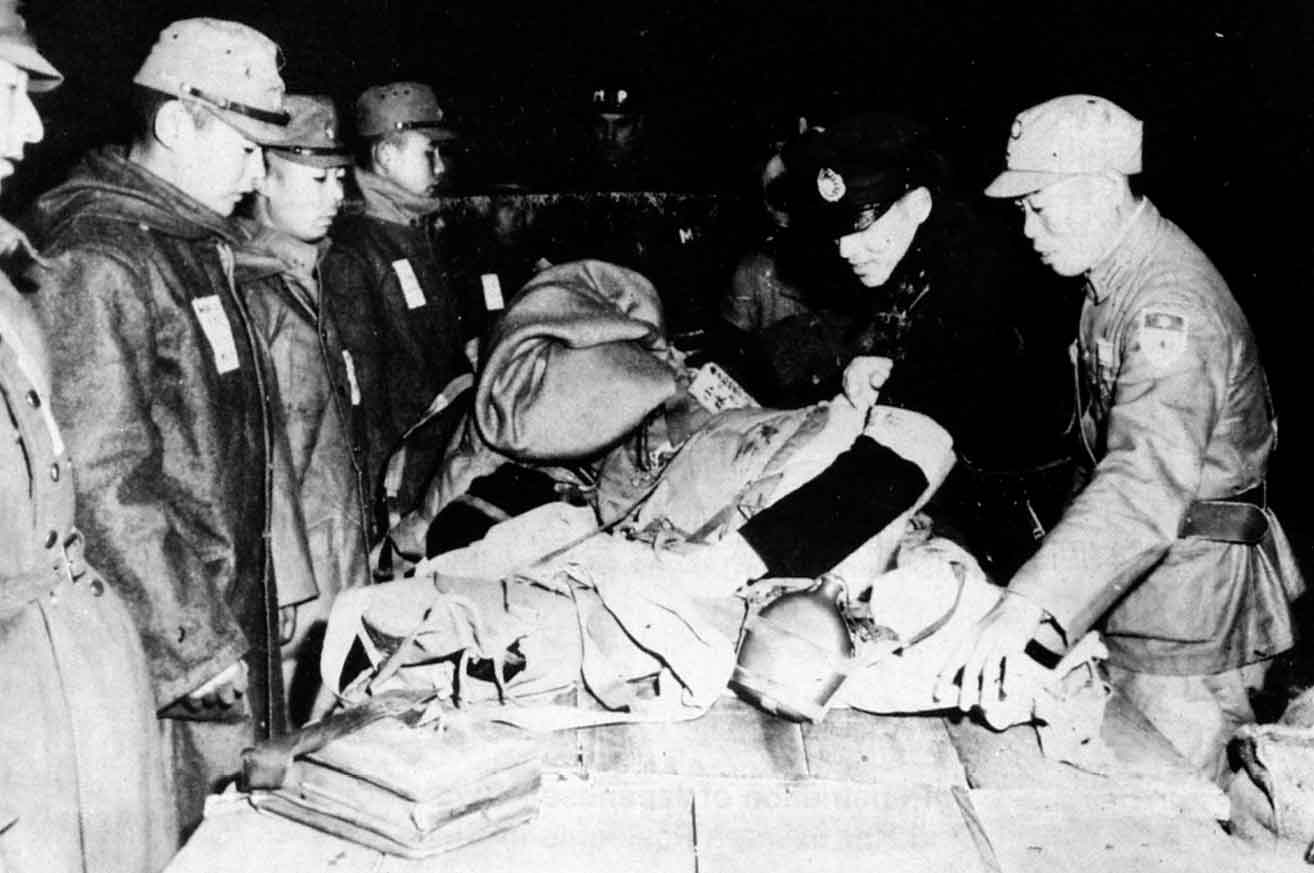

Captured Japanese soldiers are brought into Nationalist headquarters at Changteh during the battle for the city in 1943. The handful of troops captured in the battle were photographed by Western journalists as few Imperial army soldiers made the decision to surrender. As the war progressed, the Communists even had a few units fighting for them made up of turncoats and pro-Communist Japanese. Of course, any ex-Imperial army soldiers captured by their former comrades would have received little mercy.

Nationalist Major General Feng Yuan, the commander of 11th Division, plans his next move during fighting for the city of Changteh in November 1943. The city was attacked by a Japanese force of 100,000 but the Chinese garrison held out and fought the attacking Japanese back in bitter street fighting. Although the city fell to the Imperial army on 3 December, it had been recaptured by the Chinese by the 9th, forcing the Japanese to withdraw.

Exhausted Japanese troops take a well-needed break during an antiguerrilla operation in 1944. By this time the Imperial army had been fighting in China for seven years and war weariness had become a major problem. With large numbers of Japanese soldiers being transferred to the Pacific Theatre the Imperial army could not hope to defeat the Chinese. Many of the replacements sent to China from 1941 onwards were not up to the standard of the veterans.

Japanese Imperial army troops advance from their defensive position during an offensive in central China in 1944. By this stage in the war the Japanese had given up any thoughts of further territorial conquest in China and most offensives were launched simply to disrupt the Chinese war effort. Imperial army resources were being weakened as more and more troops were switched to the Pacific Theatre. This machine-gun unit is supporting a Type 94 light tank which although obsolete in all other theatres, was still being used by the Imperial army in China until 1945.

Japanese youth volunteers, making up part of the garrison at an Imperial army outpost in occupied China, march out on patrol. Isolated Japanese fortresses like this were often easy prey for the Communist guerrillas in the latter stages of the Sino-Japanese War. Both the sentry taking the salute and some of the young volunteers are armed with ‘war booty’ Mauser rifles captured from the Nationalist army.

With most sources of imported small arms cut off by 1940 the Nationalist army had to rely on its own resources. This underground armoury is producing copies of the Czech ZB-26 light machine gun while repairing others. There had always been a large number of armouries throughout China since the 1800s but their total output could never meet demand. By 1944, when this photograph was taken, some small arms were being supplied to the Chinese by the Allies. Most of these went to the troops being trained in India and western China for service in Burma.

Fighting in the ruins of the city of Teng-Chung in western Yunnan province, a Nationalist machine-gun crew fire towards Japanese positions in 1944. The machine gun is a ZB-53, sold by Czechoslovakia to Chinese in the 1930s and used in large numbers throughout the war. By this time some veterans of the Nationalist army had been fighting for seven years and had largely overcome their inferiority complex when facing their Japanese enemy. One of the crewmen has a shovel stuck in his backpack to dig in his machine gun during the heavy street fighting for the city.

Smiling Chinese Nationalist troops and their US advisor show off war booty taken from the Japanese in the fighting for Teng-Chung in September 1944. The haul includes two Japanese war flags and a few steel helmets and what appear to be a couple of Type 3 tank machine guns taken from an Imperial army light tank. An ex-Chinese MP-28 sub-machine gun, captured by the Japanese and then re-captured by the Nationalists, is held by the soldier in the middle foreground.

A US ground crewman and a Nationalist soldier defend a US airbase from Japanese air attack in early 1945. The B-29 Super Fortress bases in south-eastern China allowed the US air force to bomb Japanese cities and for this reason were a target of the 1944–5 Imperial army offensives. Interestingly, the rifle used by the Chinese soldier is a Japanese Arisaka Type 38, while his ally fires a Browning M1919 A4 machine gun.

A Nationalist 75mm PACK howitzer belonging to the Second Army is firing from a dug-in position in southern China in spring 1944. Most of these US-supplied guns were given to the forces trained in India and fighting on the Burma Front in 1944–5. This 75mm is on the older type of carriage with metal wheels instead of the newer version with tyres.

The Nationalist crew of a US-supplied M1 81mm mortar fires towards advancing Japanese divisions taking part in the Ichi-Go offensive. They are part of a force defending the large US airbase at Chihchiang to the south-west of the Nationalist capital at Chungking. One of Japan’s aims with the 1944–5 offensive was to destroy any airbases from where B-29 bombers were being launched against Japan.

Soviet-supplied T-26 light tanks rumble past a reviewing stand at a military parade in Yunnan province in 1944. These tanks are some of the survivors from the Nationalist 200th Mechanized Division which fought in Burma in 1942. Yunnan province, in western China, was one of the few regions of the country that was relatively safe from Japanese attack. It was under the control of the powerful General Lung Yun, who had remained largely independent of Chiang Kai-shek’s control since 1927.

Communist troops examine captured telephone wire and rails brought into their base by guerrillas in summer 1945. The Communists were almost completely blockaded by the Nationalist divisions during the 1941–5 period. With few military and other supplies getting into the blockaded area, the Communists had constantly to improvise. Telephone wire was used to extend their underground communication system, while rails were made into arms and ammunition in their workshops.

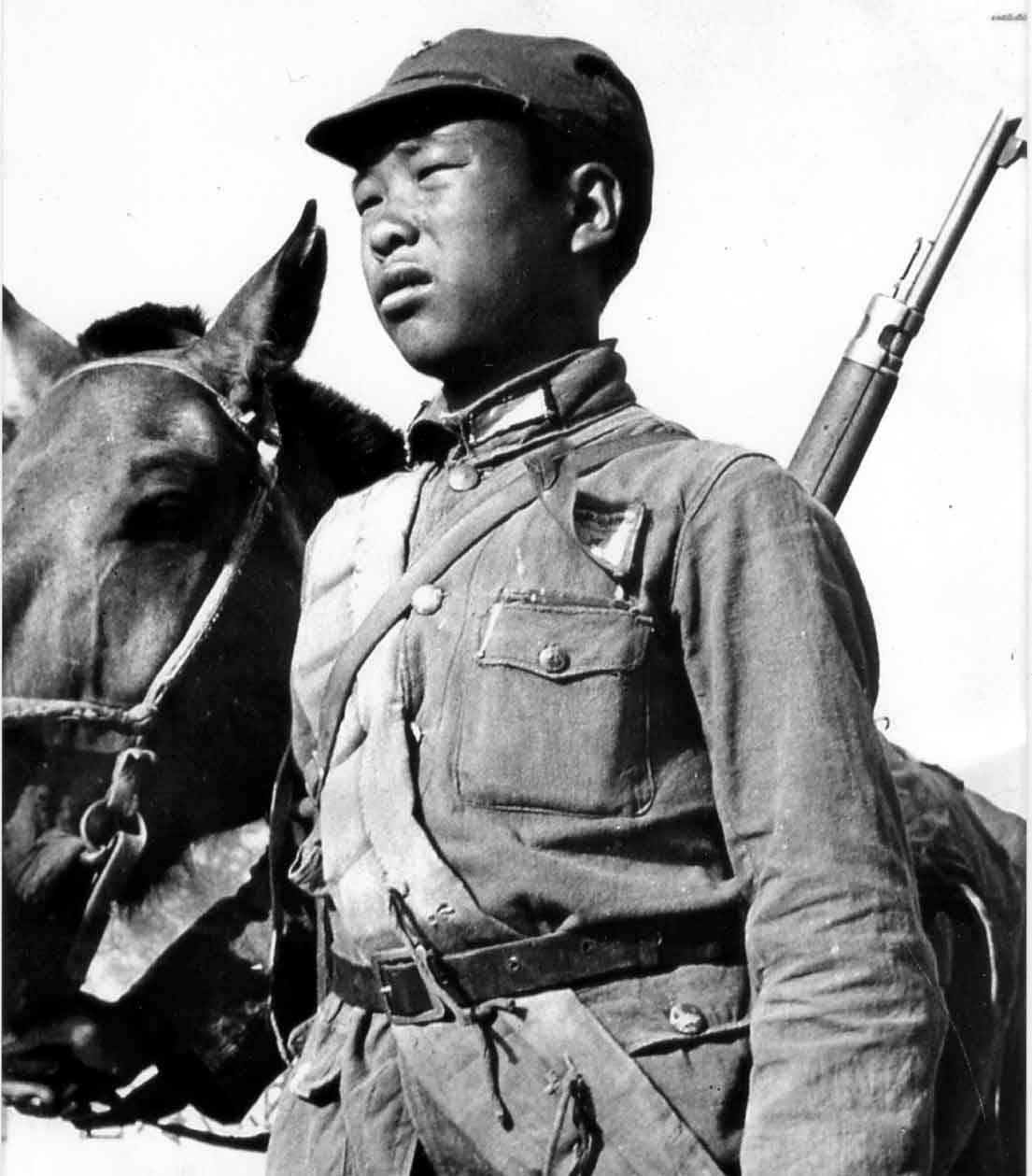

This nice image of a young Communist cavalryman in 1945 shows an elite soldier of the Chinese Red Army. The Communists made great use of their cavalry arm during the Sino-Japanese War, especially in the latter years of the conflict. This soldier’s relatively smart uniform, equipment and modern Mauser 98k rifle indicate that he belongs to one of the better cavalry units. However, the lack of clips for his rifle in the canvas bandolier over his shoulder is evidence of the shortage of ammunition suffered by the Communists.

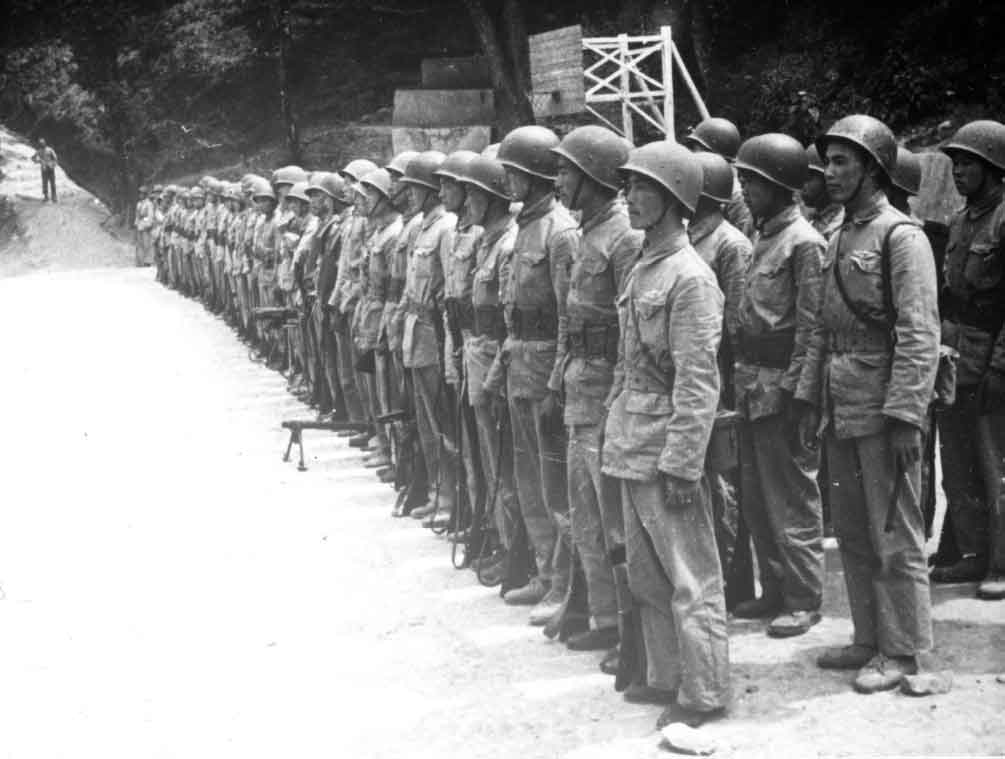

These Nationalist troops are undergoing specialist training at a US-run commando training school in May 1945. The school ran courses in irregular warfare and also a paratroopers’ course with selected Nationalist volunteers. US instructors came from the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency, and several training camps were set up in western China. Uniforms, weaponry and equipment are of US origin with P-17 rifles and Thompson sub-machine guns.

Nationalist soldiers listen to a motivational speech by their commanding officer in spring 1945. The soldiers belong to a newly organized division raised in Free China and armed and equipped from the Nationalist government’s resources. Uniforms worn by the men are locally made, as are the sandals, which may have been made by the soldiers themselves. The field caps were also manufactured in local workshops and have a cloth badge featuring a white sun on a blue sky sewn on the front. Their Mauser rifles are the short model sold to China by Czechoslovakia and Belgium in the mid- to late 1930s.

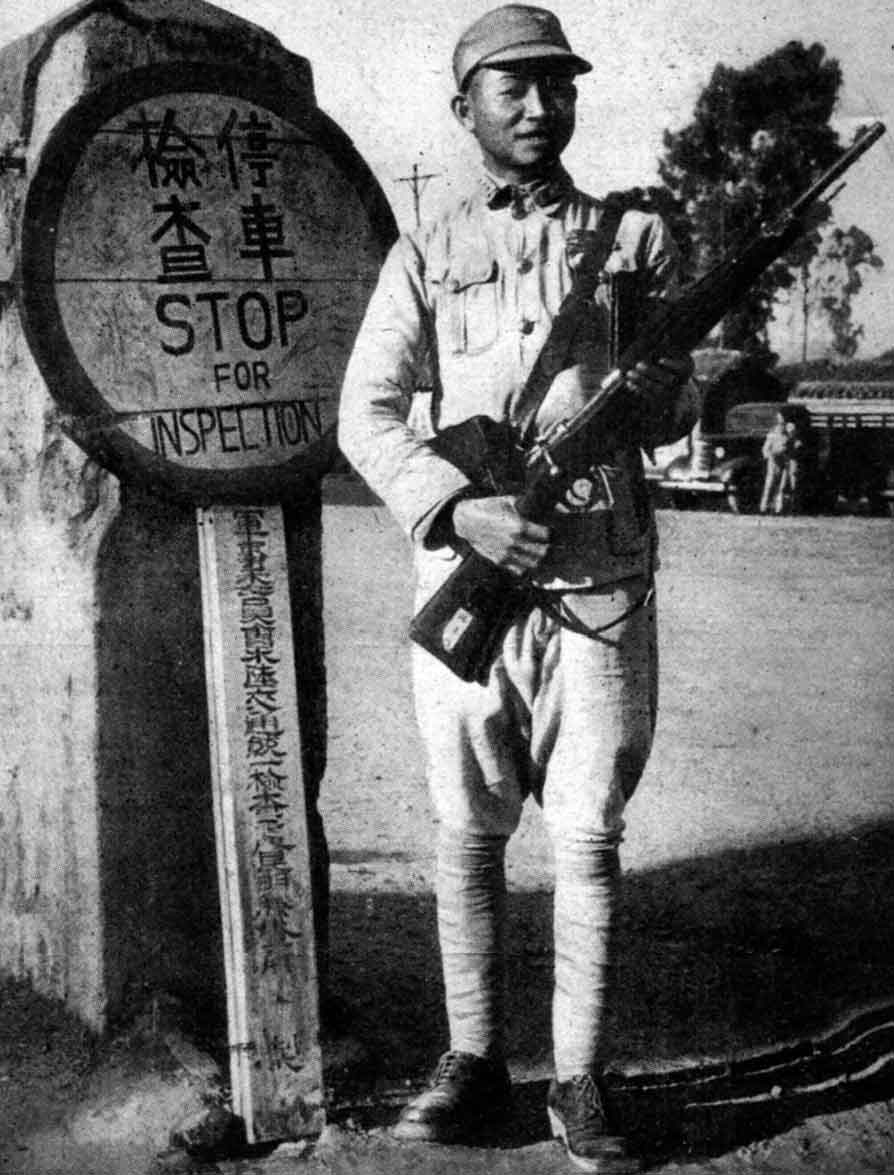

A Nationalist sentry stands guard at a roadblock at the entrance to Kunming, the capital of Yunnan province in summer 1945. It was here that the Burma Road joined the highway to the Nationalist wartime capital of Chungking. After the reopening of the Burma Road, the first convoy to Kunming reached the city on 1 February 1945. Much of the work to repair the road had been done by thousands of Chinese civilian workers labouring in terrible conditions.

Nationalist troops march through the streets of the south-western Chinese city of Kweilin in August 1944. The civilian population of the city had been largely evacuated as the Japanese Imperial army closed in. As far as can be seen in this image, none of the troops in this long column are armed.

Japanese Imperial army recruits perform a defiant banzai in the closing months of the war in China in 1945. The youth of the soldiers is noticeable and these teenage boys were sent in large numbers to fill the ranks of the depleted Kwangtung Army. Shortages of heavy weaponry was a problem for the Japanese army as tanks and artillery were shipped to Manchuria and the Pacific Islands.

The surrender of all Japanese Imperial army, naval and air force personnel in China took place on 9 September 1945. Japan was represented by General Neiji Okamura and the Nationalist government by General Ho Ying-chin. With high symbolism, the ceremony took place at the Central Military Academy in Nanking. In total, approximately 2 million military and civilian Japanese in China were to be eventually repatriated back to Japan.

Nationalist officers examine a stack of captured Japanese rifles which were part of the huge numbers of armaments surrendered to the Chinese in August 1945. Many of these rifles would find themselves in the hands of the Nationalist troops in the coming civil war with the Communists. The Communists also captured large numbers of Japanese weapons, while others were handed over to them by the Soviet army which had taken them in Manchuria in their August 1945 offensive.

Japanese troops have their kit checked before boarding ships in a northern Chinese port to be repatriated in October 1945. After the bitterness of the Sino-Japanese War the majority of Japanese soldiers and civilians were allowed to return to Japan in an orderly manner. Some Imperial army soldiers were forced to stay in China and help the Communists to train new recruits. Others freely volunteered to fight for the Communists and the Nationalists during the 1946–9 civil war.