chapter 3

Could It Be

PERIMENOPAUSE OR MENOPAUSE?

It has begun to occur to me that life is a stage I’m going through.

—Ellen Goodman

The Menstrual Cycle

To understand perimenopause and menopause, it’s essential to understand exactly how your reproductive hormonal cycle works. Many of us think we understand: the egg develops; the uterine lining builds up; the egg is released; if the egg isn’t fertilized, you shed the lining; that’s your period, and then the whole thing starts again. But it’s a much more sophisticated interrelationship of the hormones that keeps the whole cycle moving and in balance.

IN THE BEGINNING

When a girl is born, she has hundreds of thousands of immature eggs in her ovaries. These are all the eggs she will ever have.

From the age of around eight to ten the body starts producing androgens, hormones that trigger the onset of puberty. The beginning of breast development signals the start of puberty, usually followed by the appearance of pubic and underarm hair and breast buds. Around six months before the first menstrual period, vaginal discharge also frequently appears.

The first menstrual period usually occurs around twenty-four to thirty months after puberty starts, but it can start as early as a year and as late as three years. Usually, the first menstrual period won’t occur until a girl has reached around one hundred pounds and has approximately 25 percent body fat. This happens, on average, around age twelve or thirteen for most girls.

The process that triggers the first menstrual period begins when the hypothalamus sends out its first burst of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). GnRH goes to the pituitary gland, where it triggers the pituitary to release two key hormones: luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). FSH and LH in turn go to the ovaries, where they stimulate one ovary to ovulate and begin producing estrogen. Estrogen, FSH, and LH then set into motion the hormonal cycle that causes the ovary to ovulate, to release its first egg. This begins the first menstrual cycle.

THE MONTHLY CYCLE

Each ovary contains follicles—sacs—and each follicle is filled with eggs. On the first day of the menstrual cycle (referred to as day 1), the follicular phase of the cycle begins. During this phase, estrogen and progesterone are at their lowest levels. These low levels are a signal to the pituitary to begin the menstrual cycle by releasing FSH. As FSH rises, it stimulates the follicles and causes the eggs to mature. How many actual follicles develop each month is not a fixed number and is unique to each woman.

By days 5 to 7, one of these follicles responds to FSH stimulation more than the others and becomes dominant, growing faster than the other follicles. (Occasionally, with higher FSH levels, additional follicles may become dominant; this is what can cause multiple births.)

As the egg ripens inside the follicle, the follicle itself secretes estrogen, which stimulates the uterine lining to thicken and get ready for a fertilized egg). Around day 13 of the cycle, the estrogen level reaches a point where it triggers a rapid release (known as a surge) of LH. The body temperature rises for a short time. The surge of LH sets into motion the final maturation of the egg and causes the dominant follicle to force its way to the surface of the ovary to release the egg. (The LH surge is what is measured by home ovulation detection kits.)

Around day 14, the follicle ruptures, and an egg bursts out into the fallopian tube heading to the uterus, a process known as ovulation. Typically, ovulation occurs between twenty-eight and thirty-six hours after the LH surge and about twelve hours after LH reaches peak levels.

Around ovulation, the rise in estrogen makes cervical fluid stringy and sticky and more hospitable to sperm, therefore more conducive for conception. The cervix itself becomes softer and more open, again, making conception more possible.

After the egg is released, it’s swept into the fallopian tube, and if it is fertilized, this usually takes place while the egg is still in the fallopian tube.

In the meantime, as estrogen levels have been increasing, FSH production is suppressed, and FSH levels decrease.

The nondominant follicles wither away and are reabsorbed. After the dominant follicle ruptures, it collapses and becomes the corpus luteum. The corpus luteum then secretes large amounts of progesterone and some estrogen, which help prepare the uterine lining for implantation of the fertilized egg (an embryo). This built-up uterine lining is known as the endometrium.

The point of ovulation signals the end of the follicular phase and the start of the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. During this second half of the cycle, which normally runs anywhere from twelve to fifteen days, the body is attempting to support a pregnancy if one occurs.

If the egg is fertilized, a small amount of the hormone called human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) is released. (HCG, which can be detected as early as seven days after fertilization, is what is measured using early pregnancy tests.) HCG also keeps the corpus luteum viable, so it can continue to produce estrogen and progesterone to maintain the uterine lining.

If the egg was fertilized, it begins to divide and continues toward the uterus, where it may implant itself in the uterine lining. It then continues to grow into a fetus and, ultimately, a baby.

If, as in most cycles, pregnancy does not occur, around ten days after ovulation, the corpus luteum starts to disintegrate, and estrogen and progesterone levels drop.

As estrogen and progesterone levels fall sharply, days 26 to 28 can be referred to as the premenstrual phase. This is when premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is most common.

When the follicle has self-destructed completely, the drop in progesterone triggers the shedding of the endometrium as menstrual bleeding, typically starting on day 28—about 14 days after ovulation.

The time when you are bleeding, or the menstrual phase, can last from one to eight days, but the average is four or five days. The length of the bleeding period tends to remain about the same in women from month to month, but over time, it may change, becoming longer or shorter. The amount of blood lost in each menstruation tends to be similar from cycle to cycle in many women, but it can change over time and become heavier or lighter.

On the first day of menstrual bleeding—often the twenty-eighth day of the cycle—the low estrogen and progesterone levels trigger the pituitary to release FSH and start the cycle again. Day 1 of the new cycle begins.

When the entire system is working properly, the follicular phase (maturation of the egg) takes about fourteen days, and the corpus luteum, which defines the luteal phase, has a life span of approximately fourteen days. This gives the typical woman a menstrual cycle of twenty-eight days, with ovulation typically occurring around the midpoint on day 14.

- Cycle day 1

- —menstrual period begins

- Cycle days 1 to 14

- —follicular phase

- Cycle day 14

- —ovulation

- Cycle days 14 to 18

- —luteal phase

- Cycle days 26 to 28

- —premenstrual phase

- Cycle day 28/cycle day 1

- —menstrual period begins

Each woman’s cycle is unique and may not fit this “typical” twenty-eight-day schedule. Cycles can range from as little as twenty-one days to forty or more days. For most women, however, the luteal phase runs from around twelve to sixteen days. If a woman has a particularly long cycle, the additional time will usually extend the length of the follicular phase.

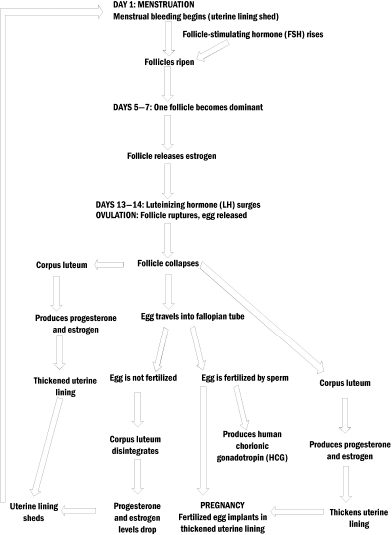

The following graphic depicts the regular menstrual cycle.

THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE

The Reproductive Hormone Pathway

To understand perimenopause/menopause, it’s important to understand the various hormones that make up what’s known as the reproductive hormone pathway.

The primary building block on the pathway for reproductive hormones is actually dietary cholesterol. The cholesterol is synthesized into pregnenolone, which acts as a precursor for other hormones used by the body. The following diagram shows a simple depiction of the reproductive hormone pathway.

It’s important to note that deficiency, conversion, or metabolic problems anywhere in the chain can interfere with levels and availability of hormones at each step in the pathway.

HORMONE PATHWAY

PREGNENOLONE

Pregnenolone is the precursor hormone, synthesized from cholesterol. Pregnenolone is a precursor for three hormones: the adrenal hormone cortisol and the reproductive hormones dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and progesterone. Because it is the precursor for all the other reproductive hormones, pregnenolone is sometimes called the “parent hormone.” Pregnenolone has roles in helping to elevate mood and energy, relieve joint pain, and improve concentration and is thought to help with brain function.

DEHYDROEPIANDROSTERONE (DHEA)

DHEA is a steroid hormone produced by the adrenal glands, as well as by the brain and the skin. DHEA levels peak around age twenty-five to thirty and steadily decline after that, so that by age eighty, the DHEA level is typically only about 15 percent of the peak level. DHEA is derived from pregnenolone and broken down into estrogen and testosterone. It helps with memory, the immune system, and muscle strength.

PROGESTERONE

Progesterone is the hormone produced by the corpus luteum of the egg follicle ovaries; after menopause, a small amount is made by the adrenal glands. It is a precursor for estrogen.

The key function of progesterone is to help prepare the uterine lining for a fertilized egg. Progesterone can help enhance mood, promote feelings of calm, and reduce anxiety.

TESTOSTERONE

Testosterone is a male hormone (androgen), but women also produce it in far smaller amounts. It is a precursor for estrogen. For women, testosterone is thought to play a role in libido, arousal, orgasmic response, energy, and muscle building.

ESTROGEN TYPES

There are actually three key types of estrogen in the body: estradiol (known as E2), estrone (E1), and estriol (E3). Estradiol is the main type of estrogen during the reproductive years and is produced by the ovaries. Estriol is the weakest of the estrogens and is made during pregnancy. Estrone is made after menopause and is most commonly found in increased amounts in postmenopausal women. Estrone does the same work in the body that estradiol does, but it is considered weaker in terms of effects.

What Happens in Perimenopause/Menopause

When we’re born, our ovaries contain follicles with as many as a million eggs. By puberty, we have around 75,000 to 300,000 eggs remaining. During our reproductive years, about 400 to 500 eggs mature and are released. The rest deteriorate over time.

Perimenopause can naturally start as early as a woman’s thirties, but it typically starts in the late thirties/early forties, as progesterone and estrogen levels start to fluctuate.

Perimenopause is triggered when baseline levels of estrogen and progesterone start to decline. At the same time, the supply of egg follicles drops, the follicles that remain are less sensitive to stimulation, and the eggs that remain are old.

Because there are fewer follicles, and because they are less sensitive, the hypothalamus stimulates the pituitary to make more FSH and LH in an attempt to stimulate the remaining follicles, cause them to mature, and trigger an LH surge. FSH levels rise in response.

In some cycles, the follicle doesn’t develop fully. Less estrogen is released in those cycles. When estrogen is especially low, it won’t trigger an LH surge, and the egg is not released at all. This is known as an anovulatory cycle. In an anovulatory cycle, the follicle doesn’t rupture and the corpus luteum isn’t produced, so there’s no release of progesterone. The drop of estrogen and progesterone levels signals the uterus to shed its lining early, so cycle length shortens and the period comes earlier than usual. (Shorter menstrual cycles and an inability to become pregnant are the most common symptoms of perimenopause.)

In other cycles, the follicle will develop normally, and normal amounts of estrogen and progesterone are released.

As the baseline levels of estrogen and progesterone decline, the monthly changes in these hormones become erratic, and the egg supply dwindles. This causes even more cycles to become anovulatory (no ovulation), and periods come more frequently, usually due to a shortened follicular phase. (The luteal phase tends to remain the same length.)

Cycles when follicles don’t develop and progesterone doesn’t rise often result in a reduction in PMS symptoms. At the same time, drops in estrogen can cause new symptoms, such as hot flashes and night sweats. As hormone levels drop further, bleeding tends to become heavier and longer and is brown rather than red. Periods can become more erratic, and with more anovulatory cycles, some periods will now be skipped entirely.

As menopause approaches, levels of circulating FSH rise dramatically, in an effort to stimulate the remaining follicles to ovulate. At the same time, the ovaries cut back on production of estrogen.

Eventually, the stock of viable eggs is depleted, and hormone levels cannot trigger ovulation. Menstruation stops, and menopause occurs.

When periods stop entirely—and this can occur hormonally or due to surgical removal of ovaries—there is a fairly dramatic drop in estrogen levels. At this point, the adrenal glands kick in to produce some estrogen. Without a corpus luteum each month, progesterone levels also drop significantly. This is a time when some women, even though estrogen has dropped, develop an imbalance, where the ratio of estrogen to progesterone is high, a condition known as estrogen dominance.

Interestingly, gynecologist and hormone expert Dr. Jerilynn Prior believes that many of the symptoms of perimenopause are actually due to estrogen dominance, not estrogen deficiency, and show signs of high estrogen or insufficient progesterone, including:

- Swollen and tender (sometimes lumpy) breasts

- Increased vaginal mucus and a heavy pelvic feeling, like cramps or swelling

- Heavy flow

- Bleeding at intervals shorter than three weeks

- Continual spotting or flow every two weeks

- Clotting with cramping

Physically, the shifts in estrogen and progesterone can cause a number of observable clinical signs in menopause, including thinning of the vaginal lining, which can make the vagina feel dry or irritated. The bladder lining also thins, which can contribute to more frequent urination, more urinary tract infections, or even incontinence. Fluctuating hormones can also disturb sleep. Skin can lose elasticity, and bone mineral density is frequently reduced.

As far as timing, in the United States, the average age when women have not had a period for a year—menopause—is fifty-one, with the common age range for natural menopause spanning from age forty-eight to fifty-five. Menopause is considered late if it occurs in a woman older than age fifty-five and premature if it occurs before forty.

The clinical “test” for menopause is elevated FSH. But because hormones can fluctuate dramatically, an elevated FSH level in a perimenopausal woman is not enough to confirm menopause. (And importantly, despite FSH levels, a woman can still get pregnant.) Measuring FSH levels can help assess the “progress” toward menopause, but until FSH is consistently elevated to 30 million International Units per milliliter (mIU/mL) or higher and a woman is no longer menstruating, menopause can’t be confirmed.

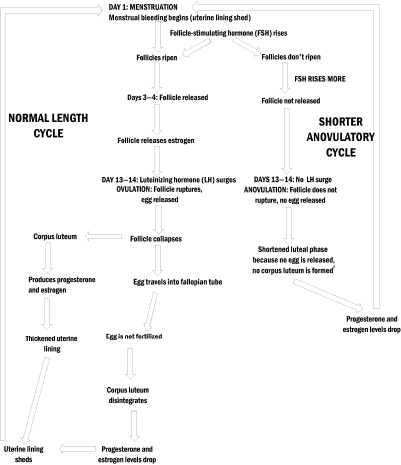

The following flowchart maps out what happens in perimenopause, in particular, why cycles can become shorter.

PERIMENOPAUSAL CYCLE

Risk Factors for Menopause

There are a number of factors that are considered “risks” for menopause.

Age

Age is the most obvious risk factor, as the closer a woman is to fifty-one (the most common age for natural menopause), the more at “risk” she is of reaching menopause. As noted before, the common age range for natural menopause spans from age forty-eight to fifty-five, but there are reports of women menstruating into their late fifties and early sixties, as well as women going through natural menopause before age forty.

Genetics/heredity

If your mother or sister had an early or late natural menopause, you are more likely to as well.

Cigarette smoking

Smoking is linked to perimenopause and menopause onset a full two years earlier than in nonsmokers.

Never being pregnant

Never having been pregnant can trigger earlier menopause, because more menstrual cycles deplete the reserve of eggs more quickly.

High altitude

Living at a high altitude is associated with earlier menopause.

Low body weight

Being excessively thin and having a low body weight can trigger an earlier menopause.

Autoimmune disease history

Having a history of autoimmune disease increases your risk of having autoimmune disease of the ovaries (that is, premature ovarian decline or premature ovarian failure), which is associated with early menopause.

Surgery

While removal of both ovaries (bilateral oophorectomy) causes immediate menopause, if the uterus is taken out and one ovary is left, a woman won’t have periods, but she may not go through menopause, though she’s at a higher risk. Ovarian surgery for adhesions or pelvic endometriosis is also associated with earlier menopause.

Childhood cancer treatment

Receiving chemotherapy or pelvic radiation cancer therapy as a child has been linked to early menopause.

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy

Having chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy to the pelvic region can cause signs and symptoms of menopause, such as hot flashes and cessation of periods, during the course of treatment. In some women, the ovarian function will start after treatment is completed. But in some cases, however, irreparable damage is done to the ovaries, and menopause is triggered.

Radioactive iodine (RAI) treatment for thyroid cancer

Women who have been treated with RAI for thyroid cancer may also experience earlier menopause. In 2001 Italian researchers reported that they’d found that RAI treatment for thyroid cancer provided sufficient radiation to damage ovarian function and follicles, reducing some women’s period of fertility and triggering earlier menopause. The patients studied were all younger than age 45 when they received their first treatment for thyroid cancer. The researchers concluded that the RAI treatment was probably a cause of earlier ovarian failure in some thyroid cancer patients.

Polycystic ovary syndrome

This endocrine disorder is associated with earlier menopause.

Extreme athleticism/overexercise

In some women, extreme athleticism or excessive exercise, such as seen in an elite athlete or a marathon runner, is associated with earlier menopause.

Eating disorders/chronic dieting

Eating disorders, such as anorexia and bulimia, and chronic dieting are associated with earlier menopause.

Vegetarianism

Being a vegetarian is associated with earlier menopause.

Drug use

Use of illegal drugs is associated with earlier menopause.

Springtime birth month

It sounds a bit wacky, but there’s actually a reputable study that found that women born in March have the earliest menopause, and that women born in October typically reach menopause as much as fifteen months later than women born in the spring. Experts don’t know what mechanism is at work; it may be diet during pregnancy, temperature, or seasonal exposure to infections.

Perimenopause/Menopause Terminology

Before we launch into a discussion of what’s happening in perimenopause and menopause, let’s get the terminology straight, because it can be confusing.

- - It’s generally agreed by medical experts that menopause refers to the point at which you have not had a menstrual period for a full year.

- - Depending on who you ask, the time before menopause can be referred to as perimenopause or premenopause. By some definitions, the perimenopause begins as long as ten years before menopause; others consider it to be the period right before menopause. This period is also sometimes referred to as menopausal transition or the climacteric. (For decades, women have referred to menopause euphemistically as “the change” or “the change of life.”) Many experts agree that the point when hormones start fluctuating erratically actually marks the start of perimenopause, and during perimenopause, menstruation typically continues, although it may not be on a regular cycle.

- Premature perimenopause: erratic menstruation and symptoms that occur before age forty are also referred to as premature ovarian decline (POD)

- Natural menopause: refers to menopause that happens for natural reasons, that is, loss of ovarian follicular function

- Surgical menopause: menopause brought on by surgical removal of both ovaries (bilateral oophorectomy) or, in some cases, removal of one ovary

- Induced menopause: menopause brought on by ablation (loss) of ovarian function by chemotherapy or radiation treatments

- Postmenopause: the period after the final menstrual period, whether menopause is natural or induced

- Premature menopause: natural or induced menopause that occurs before age forty. If natural menopause occurs before age forty, it is referred to as premature ovarian failure.

- Early menopause: natural or induced menopause before age fifty-one

Premenopausal/Menopausal Symptoms

There are a number of symptoms commonly associated with perimenopause or menopause. Some are familiar, and others might surprise you.

MENSTRUAL IRREGULARITIES

The most common menopausal symptom, more common even than hot flashes, is an irregular menstrual cycle. Changes in your period are also likely to be one of the first signs that perimenopause is under way.

You may notice changes to typical PMS symptoms. Some women have fewer symptoms during perimenopause. A smaller percentage have worsening PMS during perimenopause.

Earlier in perimenopause, when you are having anovulatory cycles, it’s more common to have periods that come more frequently—even every twenty-one days or so.

Later in perimenopause, it’s more common to have a longer interval between periods, with many women going thirty-six days or more between periods. In some cases, you may skip a period entirely and pick back up the next month. Some women find that their period stops for a few months, then starts again. Midcycle spotting is also common.

Carolina, like the other women in her family, started her perimenopause in her late thirties.

Now, my periods are becoming longer and longer apart. I went seven months without a period, and then it showed up again this past December. Now I haven’t had a period since then, but I don’t know if it is because I’m through menopause or if it is going to show up again. It’s so hard because you really don’t know what is going on or what is causing what.

Some women have what are known as phantom periods. In a phantom period, you have all the signs and symptoms that your period is coming, but it never does.

The length of periods can change as well. If you typically menstruated for five days, you may find that your period gets shorter or longer. Periods can also become lighter or heavier. In fact, a sign that you are getting closer to menopause is that your period may become heavier and last longer. But other women find that they have less menstrual discomfort during perimenopausal periods.

The way the menstrual blood looks also can change. In perimenopause, menstrual blood may take on a brown tinge, and it’s not uncommon for the blood to contain heavy clots.

Keep in mind, however, that you can still become pregnant during this period, as you may ovulate during some cycles, and your fertile period may be difficult to predict or identify.

At age forty-six, Anita, who had her thyroid removed, was struggling. Says Anita:

My periods started getting heavy for the first three days. This went on for a while. Then my period started getting really heavy with clots, almost gushing as if I were having a miscarriage to the point where I changed my clothes three or four times a day while wearing two extra long pads. My OB-GYN said nothing was wrong, and it was probably perimenopause. This went on for a while. Then I stopped for about three, almost four months. They did blood work: I was not menopausal. They gave me pills to jump-start my period again. From that point, I was having a period one month, then off two months.

While some bleeding irregularities can be expected during perimenopause, any significant irregular bleeding does need to be evaluated. Some of the causes of abnormal bleeding during perimenopause are

- Hypothyroidism: untreated or improperly treated hypothyroidism can cause excessive bleeding in some women.

- Pregnancy: a normal pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, or miscarriage

- Fibroids: noncancerous growths in and around the uterus, known as fibroids, can cause bleeding.

- Uterine lining abnormalities: polyps in the endometrium (uterine lining) or overgrowth of the endometrium can cause abnormal bleeding.

- Cancer: uterine, vaginal, or cervical cancer is a rare cause of abnormal bleeding.

All postmenopausal bleeding must be evaluated promptly by a physician.

DECREASING FERTILITY/INFERTILITY

Clearly, one of the key symptoms of perimenopause is decreasing fertility. As ovulation becomes less regular, the ability to conceive drops, and after age forty, fertility is estimated to drop by at least 50 percent in most women. The risk of miscarriage after forty is two to three times that of younger women.

As long as you are still having periods—as erratic as they may be—and until you’ve hit point where it’s been at least twelve months since your last period, it is still possible for you to become pregnant. (We’ve all known someone who had a “change of life” baby.) Women who don’t want to become pregnant still need to use birth control during this time.

HOT FLASHES/NIGHT SWEATS

Cartoonist and writer Dee Adams runs the wonderful Minnie Pauz Web site, which features a selection of hilarious cartoons about menopause. What topic has the most cartoons dedicated to it? Hot flashes, of course!

Hot flashes (also known as hot flushes) and their evening counterpart, night sweats, are perhaps the most iconic symptoms of menopause. Together, hot flashes and night sweats are referred to as the climacteric syndrome and vasomotor symptoms.

It’s estimated that 75 to 85 percent of women experience hot flashes and night sweats. After menstrual irregularities, they are the most common perimenopausal symptoms. There appears to be a greater risk of hot flashes in women who have a higher body mass or who are obese, in women who smoke, and in women who don’t exercise. Women who suffer from high anxiety report four times the rate of hot flashes compared with those with low anxiety.

Hot flashes tend to occur sporadically and can start several years before any other signs of menopause. They also tend to get worse the further into perimenopause and the closer you are to actual menopause—the last period—and are still common into the first three years after menopause. Generally, however, about 80 percent of women with hot flashes have them for less than two years, and a very small percentage have them for more than five years.

More than 80 percent of women who have hot flashes have them for more than a year, but they gradually decline in frequency and intensity over time. Untreated, most hot flashes do stop spontaneously, although it’s estimated that approximately 10 percent of women continue to have hot flashes beyond menopause and even into their seventies.

Hot flashes can range in frequency from hourly, to all day and night, to several a day, to just the occasional flash. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration actually defines “mild” hot flashes as those that occur fewer than seven times a day, on average.

In the United States, hot flashes are more common in African-American and Latina women and less common in Chinese-American and Japanese-American women, versus Causasian women.

Hot flashes are more common in the evening and during hot weather. Some women find that there are certain triggers associated with hot flashes, including caffeine, alcohol (especially red wine), hot drinks, spicy foods, chocolate, refined sugar, and stressful or frightening events.

Some hot flashes start with nausea or a headache, but the typical hot flash begins as a feeling of warmth or heat that starts in the abdomen or bellybutton area and moves up toward the head and face. The rapid sensation of heat then affects the face and upper chest area for anywhere from thirty seconds to five minutes. During the hot flash, skin temperature can go up by as much as ten degrees, and a woman may have sweating of the head and upper body. The face may flush or turn red, and some women get blotchy red patches on the chest, back, and arms. During the hot flash, the heart rate typically goes up as much as seven to fifteen beats per minute, and heart palpitations are common. Some women also have dizziness, light-headedness, and vertigo during a hot flash. After the hot flash is done, the skin temperature returns to normal, which can cause cold chills, heavy sweating, and even shivering in some women.

Hot flashes that occur at night—night sweats—are the main cause of sleep problems and insomnia in perimenopausal and menopausal women. Strong night sweats, which are more likely during the first four hours of sleep, can actually wake a woman out of a deep sleep. Mood symptoms and memory problems are more common in women who have nighttime hot flashes, but experts are not clear on how they are linked. Treating the hot flashes reportedly can help improve memory function in women with hot flashes.

The conventional wisdom is that hot flashes are due to declining estrogen levels. The hypothalamus mistakes low estrogen levels in the body as a drop in body temperature. The message goes out for the blood vessels to rapidly expand. Blood flow to the extremities and skin drops, and skin temperature rises in response.

Gynecologist Jerilynn Prior, MD, who is founder of the Centre for Menstrual Cycle and Ovulation Research in Vancouver, has a theory that it’s a bit more complicated than simply “declining estrogen.” At her Web site, Dr. Prior writes:

Hot flushes occur in both perimenopause and menopause, yet hormone levels are very different. Why? Hot flushes appear to be caused by dropping estrogen levels when the brain has been exposed to, and gotten “used to,” higher estrogen levels. Therefore, the hot flushes in perimenopause occur because of the big swings in estrogen from super-high to merely high, or even from high to normal. In menopause, hot flushes occur because estrogen levels have become low after the normal levels of the menstruating years and the higher levels of perimenopause. Although no one has tracked the life experience of hot flushes within a woman, as opposed to in categories of women, I suspect that most women who are going to get hot flushes—except those with surgical menopause or who stop estrogen therapy—start having them before they are officially menopausal.

Some studies have also found that higher FSH levels are correlated to incidence of hot flashes.

SLEEP PROBLEMS

As discussed earlier, some women who have night sweats have significant sleep problems as a result.

Night sweats can cause frequent waking and insomnia. If women find it difficult to fall back to sleep after waking, they may also suffer from exhaustion, memory problems, and depression as a result.

Decreasing estradiol levels (estradiol is the key form of estrogen) also are associated with trouble falling asleep and frequent waking. Elevated FSH is linked to frequent waking.

Some women have erratic sleep or sleep problems without any night sweats. Some of the common problems are

- Difficulty falling asleep

- Frequent waking

- Waking frequently to urinate

- Inability to go back to sleep after waking

- Waking early

Waking earlier than planned tends to become more common through late perimenopause, but sleep habits improve when women are postmenopausal.

WEIGHT GAIN AND REDISTRIBUTION

During perimenopause and into menopause, many women experience weight gain, a redistribution of body fat, and a decrease in muscle mass. Women find that they may gain weight or that fat is redistributed to the abdomen, waist, hips, and thighs. Other women find that it becomes harder to lose weight or easier to gain.

According to the North American Menopause Society, over the average six years of menopause transition, women typically gain seven pounds and two to three inches at the waist. Another study found that women gain an average of five pounds in the three years before menopause.

There is a biological reason for this weight gain, in that extra fat can help to produce estrogen to replace the estrogen lost during perimenopause.

Researchers believe that specialized estrogen receptors in the hypothalamus may be acting as a master switch that controls food intake, energy expenditure, and body fat distribution. They theorize that dropping estrogen levels may cause women to eat more, burn less energy, gain weight, and redistribute body fat directly to the waist, hips, thighs, and abdomen. It’s also theorized that estrogen helps the brain remain sensitive to leptin, a hormone that helps regulate energy intake, energy expenditure, appetite, and metabolism.

Some women in perimenopause and menopause report increased cravings for starchy carbohydrates (bread, potatoes, rice, and pasta) and chocolate, which may also contribute to weight gain. Cravings in menopause haven’t been studied extensively, but it’s thought that dropping serotonin levels in the brain many intensify cravings for sugary, high-carbohydrate foods. Some menopausal women also report craving caffeine, which may be a result of fatigue or sleep disturbances.

There is some evidence that blood sugar imbalances are more common during perimenopause and menopause.

MOOD CHANGES

Perimenopause/menopause is a time when many women experience a variety of mood changes. Estrogen helps elevate mood, and progesterone is a relaxant. It’s thought that imbalances and drops in both hormones affect mood.

Some of the complaints reported by perimenopausal and menopausal women are feeling extreme irritability, tension, anger, rapid mood swings, inability to cope with stress, extreme emotionality (for example, bursting into tears), and anxiety.

The greatest incidence of depression in perimenopausal/menopausal women appears to be in the two years after the last menstruation, but this typically lifts. (Interestingly, research has shown that women tend to be more depressed in their twenties and thirties than during or after menopause.) Surgical menopause is an exception, however, and women have double the rate of depression after surgical menopause, when compared with women experiencing natural menopause.

Women who are experiencing sleep problems, hot flashes, or night sweats are more likely to report mood-related symptoms.

Gynecologist and menopause expert Jan Shifren, MD, says that women should be aware that short bursts of anxiety can be a perimenopausal symptom. Says Dr. Shifren:

I had a perimenopausal patient who reported that she was not having any hot flashes, and had no history of anxiety or depression. She was having these unusual episodes, however, each lasting around five minutes, where her heart would race and she felt incredibly anxious, and then it would pass. They sounded just like classic hot flashes, except without the heat. I suspected that she was having vasomotor symptoms due to estrogen fluctuating, and it appears to be the case, because after treating her with low-dose estrogen, these episodes disappeared.

VAGINAL/OVARIAN/UTERINE PROBLEMS

When estrogen levels drop, the tissues that line the vagina and vulva become drier, thinner, and less elastic. This causes a variety of symptoms.

From 40 to 60 percent of menopausal women find that they need more time and sexual stimulation in order to become lubricated. It is this reduced lubrication that is responsible for painful intercourse, a condition known as dyspareunia, which is more common in women after menopause.

The dryness and lack of lubrication can also result in itching and burning. Women also become more susceptible to vaginal infections. The pH of the vagina changes, shifting from acidic to alkaline, which makes it more susceptible to infections, including atrophic vaginitis and bacterial vaginosis (which can cause a fishy odor and discharge).

Because of the thinness of the vaginal tissue, some women have light spotting after sex.

About 30 percent of women report these sorts of vaginal symptoms during the early postmenopausal period, and almost half complain of these problems after menopause. Unlike hot flashes, vaginal symptoms generally persist, and they tend to get worse with aging.

There is also an increased incidence of ovarian problems, including benign ovarian cysts and fibroids, during perimenopause and menopause.

Women can lose some tone in the pelvis, and this can result in a drop (known as a prolapse) in the reproductive and urinary tract organs, such as the uterus and bladder. Prolapse can cause a feeling of pressure in the vagina, as well as pain and pressure in the lower back.

BLADDER/URINARY PROBLEMS

During perimenopause and after menopause, as estrogen drops, the tissues in the urinary tract and the opening to the bladder (the urethra) also typically become drier, thinner, weaker, and less elastic. This can trigger two key symptoms: incontinence and infection.

Incontinence refers to the involuntary loss or leaking of urine. Among women in menopause, it’s estimated that as many as half of all women have some mild problem with incontinence, and 5 to 15 percent have more severe problems.

There are two types of incontinence. “Stress” incontinence refers to leaking urine when coughing, laughing, sneezing, running, or during physical activity. “Urge” incontinence is an intense, sudden urge to urinate that occurs even after emptying the bladder, or a feeling that you have to go to the bathroom all the time. In some cases, a woman may also feel that she can’t get to the bathroom quickly enough and begins to leak urine.

In the four or five years after menopause, the thinning of the bladder and urethra causes women to have an increased risk of infections in the urinary tract, including urinary tract infections (UTIs, also known as bladder infections) and cystitis. Symptoms of infection include frequent urination, urinary urgency, difficulty urinating, and a burning sensation when urinating. These infections are treatable with antibiotics, but they tend to recur.

LOSS OF SEX DRIVE

During perimenopause and menopause, the drops in estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone levels can dampen sexual desire, a condition known as loss of libido. In addition to the hormones’ effects on desire, the dryness of the vagina can make sex painful, which can affect a woman’s sex drive. The ability to become aroused may also suffer, and some women experience difficulty with orgasm. Some women become less interested in sex because of negative self-esteem related to body image or aging.

As many as half of all women have some drop in sexual desire after menopause.

The good news is that, typically, women who had satisfactory sexual intimacy before menopause continue through perimenopause and beyond. Some women report greater interest in sex after menopause, because the fear of pregnancy is gone, and children are often out of the house.

HAIR LOSS/UNWANTED HAIR

Hair problems are a troublesome symptom for many perimenopausal/menopausal women. It’s estimated that half of all women have some thinning and hair loss before age fifty, including:

- Thinning of hair from the head or body

- Loss of hair from the head or body

- Receding male-pattern hair loss at the temples (known as androgenic alopecia)

The hair loss is most often due to changes in the estrogen/testosterone balance.

While hair loss is a concern, these imbalances can result in hair growing in places where it’s not wanted, such as the chin, upper lip, chest, and abdomen.

SKIN CHANGES

As estrogen levels drop, collagen, which gives skin its strength and elasticity, is reduced. Less collagen makes skin thinner, more fragile, and drier, and wrinkles become more prominent. Increasing dryness can also make skin look older and more wrinkled. The layer of fat under the skin tends to thin, which can make wrinkles more visible.

Many women report developing thin vertical wrinkles above the lips, as well as thinning and drying of the lips themselves.

The fluctuations in hormones can also trigger adult-onset acne.

FORMICATION/ITCHINESS/TINGLING SENSATIONS

A symptom some women experience during perimenopause/menopause is called formication, or strange sensations in the skin.

Formication is described as a feeling that resembles insects crawling on or under the skin. Some people describe it as an itchy or even “tingly” sensation.

BONE LOSS

As estrogen declines, women lose bone more quickly than they replace it, resulting in a more rapid loss of bone density.

The optimal bone density for women is usually seen when they are twenty-five to thirty years old. After age thirty, bone density begins to drop, at a rate of less than 1 percent per year. During perimenopause, the bone density loss steps up to as much as 3 percent each year. After menopause, the rate steadies at about 2 percent per year.

Reduced bone mineral density increases the risk of osteoporosis, a disease that weakens bones and increases the risk of disabling or even fatal fractures.

According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF), osteoporosis is a major public health threat for more than half the population of people fifty years of age and older. According to the NOF, some 10 million individuals already have osteoporosis, and 34 million more are estimated to have low bone mineral density, placing them at increased risk for osteoporosis.

ELEVATED CHOLESTEROL LEVELS

As estrogen levels drop, some women have an increase in the levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol—known as “bad” cholesterol—as well as the total cholesterol level. At the same time, as we age, levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol—the “good” cholesterol—tend to drop.

The combination of increasing “bad” cholesterol and dropping “good” cholesterol increases the risk of heart disease.

FATIGUE/LACK OF ENERGY

Fatigue/lack of energy is a symptom that many women associate with perimenopause and menopause.

Some women have a higher level of exhaustion, in general, or need somewhat more sleep in order to feel refreshed. Other women report what’s known as “crashing fatigue,” which is rapid onset of deep and overwhelming exhaustion that is not related to exertion, sleep, or exercise.

While there is no direct scientific link that says “menopause causes fatigue” or “low estrogen causes fatigue,” there are many mechanisms that may be at play. Progesterone is a relaxant, and low progesterone levels in perimenopause and menopause may contribute to anxiety and difficulty sleeping. Other sleep disturbances in perimenopause/menopause can lead to daily fatigue. Also, the adrenal slowdown that can sometimes accompany sex hormone fluctuations can contribute to fatigue.

ACHES AND PAINS

Body aches and pains, along with sore joints, backaches, leg cramps, and muscle tension, are all symptoms that appear to increase in women during perimenopause and menopause. Interestingly, among Japanese women, shoulder stiffness is considered the most severe menopausal complaint and overshadows even hot flashes.

GASTROINTESTINAL/DIGESTIVE DISTURBANCES

Some women going through perimenopause and menopause report an increase in gastrointestinal and digestive symptoms, including heartburn, indigestion, flatulence, gas pains, nausea, food intolerances, constipation, and bloating/water retention.

DRYNESS

With the drop of estrogen, some women experience dryness not only in the vaginal area, but also in the eyes and mouth. Dry eyes can cause excessive watering, stinging, burning, grittiness, scratchiness, and a sensation that something is in the eye. Dry mouth can contribute to gum problems like gingivitis, increased bleeding, bad breath, a burning tongue, burning feeling in the roof of the mouth, bad taste in the mouth, a change in breath odor, and an increase in dental cavities.

BREAST CHANGES

Menopause may cause changes in the breasts, and women report not only breast tenderness and an increase in lumpy and fibrocystic breasts, but also shrinking, sagging, and reduced firmness.

During perimenopause and menopause, breasts tend to lose muscle and gain fat, which contributes to the sagging.

HEART-RELATED PROBLEMS

During perimenopause and menopause, some women experience heart-related symptoms, including periods of rapid heartbeat, heart palpitations, and an irregular heartbeat, often accompanying hot flashes. While these uncomfortable symptoms are often harmless, women experiencing any heart irregularities need to be evaluated by a doctor before assuming the symptoms are due to perimenopause.

During perimenopause/menopause, women also face an increased risk of heart disease. It’s not clear how much of this risk is due to aging, lifestyle, diet, and exercise and how much is caused by the hormonal changes that occur at the time of menopause. But we know that estrogen plays a role, because women who undergo premature menopause or have their ovaries removed surgically at an early age are also at an increased risk of heart disease.

CONCENTRATION AND MEMORY PROBLEMS

According to the North American Menopause Society, 62 percent of women complain of difficulty concentrating, forgetting things more easily, difficulty multitasking, and memory lapses during perimenopause and menopause. Some women refer to it as “brain fog” or “cotton brain.” The concentration and memory issues may be due to disrupted sleep and fatigue, but some experts speculate that, because the brain has hundreds of estrogen receptors, a drop in estrogen levels may negatively affect brain function.

HEADACHES/MIGRAINES

Some women who have suffered migraines or chronic headaches report that in perimenopause/menopause, the headaches decrease or even disappear. At the same time, other women report an increase in chronic headaches or migraines.

According to headache and migraine disease expert Teri Robert:

Hormonal fluctuations are frequently a migraine trigger for women. Menopause can be a confusing and frustrating time for women with migraines. Women are often told that their migraines will stop after menopause, but this is not necessarily true. Women for whom monthly hormonal fluctuations have been a lifelong migraine trigger may indeed experience far fewer migraines during and after menopause, but they may also experience more migraines.

OTHER SYMPTOMS

Other symptoms that are more common in perimenopausal and menopausal women, and that may be related to fluctuating hormones, are

- Dizziness, light-headedness, losing your balance

- Changes in body odor

- Changes in foot odor

- Dry, brittle fingernails

- Tinnitus (a ringing, buzzing, or whooshing sound in the ears)

- Varicose veins