Once you have decided to participate in the stock market, you are faced with more decisions than just which stock to purchase. You have to decide how you will handle your portfolio, how many stocks you should buy, what types of actions you will take, and what types of investments are better left alone.

This and the following chapter will introduce you to the many options and alluring diversions you have at your disposal. Some of them are beneficial and worthy of your attention, but many others are overly risky, extremely complicated, or unnecessarily distracting and less rewarding. Regardless, it helps to be informed and to know as much about the investing business as possible—if for no other reason than to know all the things you should avoid. I say don’t make it too complicated; keep it simple.

How many times have you been told, “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket”? On the surface, this sounds like good advice, but my experience is that few people do more than one or two things exceedingly well. Those who are jacks-of-all-trades and masters of none are rarely dramatically successful in any field, including investing. Did all the esoteric derivatives help or harm Wall Street pros? Did experimenting with highly abnormal leverage of 50 or 100 to 1 help or hurt them?

Would you go to a dentist who did a little engineering or cabinetmaking on the side and who, on weekends, wrote music and worked as an auto mechanic, plumber, and accountant?

This is true of companies as well as people. The best example of diversification in the corporate world is the conglomerate. Most large conglomerates do not do well. They’re too big, too inefficient, and too spread out over too many businesses to focus effectively and grow profitably. Whatever happened to Jimmy Ling and Ling-Temco-Vought or to Gulf+Western Industries after the conglomerate craze of the late 1960s collapsed? Big business and big government in America can both become inefficient, make many mistakes, and create nearly as many big new problems as they hope to solve.

Do you remember when Mobil Oil diversified into the retail business by acquiring Montgomery Ward, the struggling national department-store chain, years ago? It never worked. Neither did Sears, Roebuck’s move into financial services with the purchases of Dean Witter and Coldwell Banker, or General Motors’s takeover of computer-services giant EDS, or hundreds of other corporate diversification attempts. How many different businesses and types of loans was New York’s Citigroup involved in from 2000 to 2008?

The more you diversify, the less you know about any one area. Many investors overdiversify. The best results are usually achieved through concentration, by putting your eggs in a few baskets that you know well and watching them very carefully. Did broad diversification protect your portfolio in the 2000 break or in 2008? The more stocks you own, the slower you may be to react and take selling action to raise sufficient cash when a serious bear market begins, because of a false sense of security. When major market tops occur, you should sell, get off margin if you use borrowed money, and raise at least some cash. Otherwise, you’ll give back most of your gains.

The winning investor’s objective should be to have one or two big winners rather than dozens of very small profits. It’s much better to have a number of small losses and a few very big profits. Broad diversification is plainly and simply often a hedge for ignorance. Did all the banks from 1997 to 2007 that bought packages containing 5,000 widely diversified different real estate loans that had the implied backing of the government and were labeled triple A protect and grow their investments?

Most people with $20,000 to $200,000 to invest should consider limiting themselves to four or five carefully chosen stocks they know and understand. Once you own five stocks and a tempting situation comes along that you want to buy, you should muster the discipline to sell your least attractive investment. If you have $5,000 to $20,000 to invest, three stocks might be a reasonable maximum. A $3,000 account could be confined to two equities. Keep things manageable. The more stocks you own, the harder it is to keep track of all of them. Even investors with portfolios of more than a million dollars need not own more than six or seven well-selected securities. If you’re uncomfortable and nervous with only six or seven, then own ten. But owning 30 or 40 could be a problem. The big money is made by concentration, provided you use sound buy and sell rules along with realistic general market rules. And there certainly is no rule that says that a 50-stock portfolio can’t go down 50% or more.

It’s possible to spread out your purchases over a period of time. This is an interesting form of diversifying. When I accumulated a position in Amgen in 1990 and 1991, I bought on numerous days. I spread out the buying and made add-on buys only when there was a significant gain on earlier buys. If the market price was 20 points over my average cost and a new buy point occurred off a proper base, I bought more, but I made sure not to run my average cost up by buying more than a limited or moderate addition.

However, newcomers should be extremely careful in trying this more risky, highly concentrated approach. You have to learn how to do it right, and you positively have to sell or cut back if things don’t work as expected.

In a bull market, one way to maneuver your portfolio toward more concentrated positions is to follow up your initial buy and make one or two smaller additional buys in stocks as soon as they have advanced 2% to 3% above your initial buy. However, don’t allow yourself to keep chasing a stock once it’s extended too far past a correct buy point. This will also spare you the frustration of owning a stock that goes a lot higher but isn’t doing your portfolio much good because you own fewer shares of it than you do of your other, less-successful issues. At the same time, sell and eliminate stocks that start to show losses before they become big losses.

Using this follow-up purchasing procedure should keep more of your money in just a few of your best stock investments. No system is perfect, but this one is more realistic than a haphazardly diversified portfolio and has a better chance of achieving important results. Diversification is definitely sound; just don’t overdo it. Always set a limit on how many stocks you will own, and stick to your rules. Always keep your set of rules with you—in a simple notebook, perhaps—when you’re investing. What? You say you’ve been investing without any specific buy or sell rules? What results has that produced for you over the last five or ten years?

If you do decide to concentrate, should you invest for the long haul or trade more frequently? The answer is that the holding period (long or short) is not the main issue. What’s critical is buying the right stock—the very best stock—at precisely the right time, then selling it whenever the market or your various sell rules tell you it’s time to sell. The time between your buy and your sell could be either short or long. Let your rules and the market decide which one it is. If you do this, some of your winners will be held for three months, some for six months, and a few for one, two, or three years or more. Most of your losers will be held for much shorter periods, normally between a few weeks and three months. No well-run portfolio should ever, ever have losses carried for six months or more. Keep your portfolio clean and in sync with the market. Remember, good gardeners always weed the flower patch and prune weak stems.

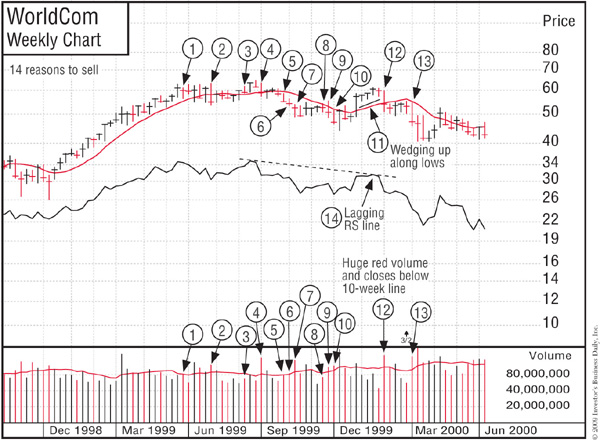

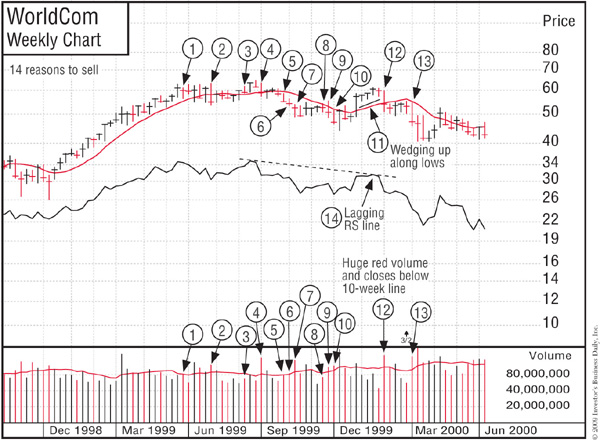

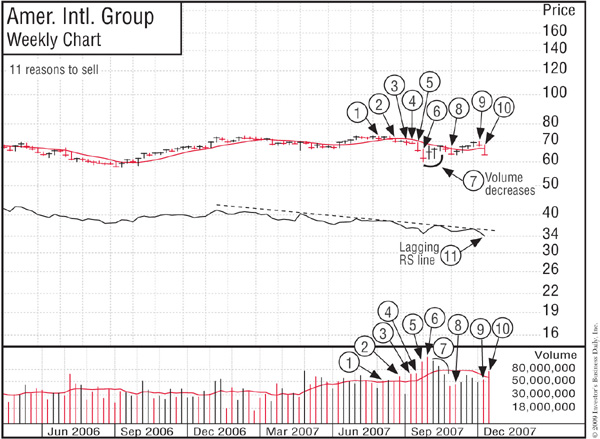

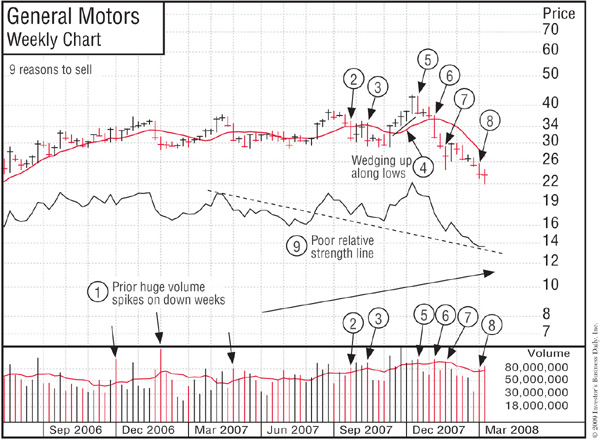

I’ve marked up the weekly charts of WorldCom in 1999, Enron in 2001, and AIG, Citigroup, and General Motors in 2007. They show 10 to 15 specific signs that these investments should clearly have been sold at that time.

Why you must always use charts...see what happens next.

Actually, if you looked at a longer time period, there were even more sell signals. For example, Citigroup had dramatically underperformed on a relative strength basis for the prior three years, from 2004 through 2006, and its earnings growth during that time slowed from its growth rate throughout the 1990s. It pays to monitor your investments’ price and volume activity. That’s how you stop losing and start winning.

One type of investing that I have always discouraged people from doing is day trading, where you buy and sell stocks on the same day. Most investors lose money doing this. The reason is simple: you are dealing predominantly with minor daily fluctuations that are harder to read than basic trends over a longer time period. Besides, there’s generally not enough profit potential in day trading to offset the commissions you generate and the losses that will inevitably occur. Don’t try to make money so fast. Rome wasn’t built in a day.

There is a new form of day trading that is more like short-term swing trading (buying a stock on the upswing and selling before an inevitable pull-back). It involves buying a stock at its exact pivot buy point off a chart (coming out of a base or price consolidation area) and selling it five or so days later after the breakout. Sometimes pivot points off patterns such as the cup-with-handle pattern (see Chapter 2) identified on intraday charts of five-minute intervals can reveal a stock that is breaking out from an intraday pattern. If this is done with real skill in a positive market, it might work for some people, but it requires lots of time, study, and experience.

In the first year or two, while you’re still learning to invest, it’s much safer to invest on a cash basis. It usually takes most new investors at least two to three years before they gain enough market experience (by making several bad decisions, wasting time trying to reinvent the wheel, and experimenting with unsound beliefs) to be able to make and keep significant profits. Once you have a few years’ experience, a sound plan, and a strict set of both buy and sell rules, you might consider buying on margin (using borrowed money from your brokerage firm in order to purchase more stock). Generally, margin buying should be done by younger investors who are still working. Their risk is somewhat less because they have more time to prepare for retirement.

The best time to use margin is generally during the first two years of a new bull market. Once you recognize a new bear market, you should get off margin immediately and raise as much cash as possible. You must understand that when the general market declines and your stocks start sinking, you will lose your initial capital twice as fast if you’re fully margined than you would if you were invested on a cash basis. This dictates that you absolutely must cut all losses quickly and get off margin when a major general market deterioration begins. If you speculate in small-capitalization or high-tech stocks fully margined, a 50% correction can cause a total loss. This happened to some new investors in 2000 and early 2001.

You don’t have to be fully margined all the time. Sometimes you’ll have large cash reserves and no margin. At other times, you’ll be invested on a cash basis. At still other points, you’ll be using a small part of your margin buying power. And in a few instances, when you’re making genuine progress in a bull market, you may be fully invested on margin. All of this depends on the current market situation and your level of experience. I’ve always used margin, and I believe it offers a real advantage to an experienced investor who knows how to confine his buying to high-quality market leaders and has the discipline and common sense to always cut his losses short with no exceptions.

Your margin interest expense, depending on laws that change constantly, might be tax-deductible. However, in certain periods, margin interest rates can become so high that the probability of substantial success may be limited. To buy on margin, you’ll also need to sign a margin agreement with your broker.

If a stock in your margin account collapses in value to the point where your stockbroker asks you to either put up money or sell stock, don’t put up money; think about selling stock. Nine times out of ten, you’ll be better off. The marketplace is telling you that you’re on the wrong path, you’re getting hurt, and things aren’t working. So sell and cut back your risk level. Again, why throw good money after bad? What will you do if you put up good money and the stock continues to decline and you get more margin calls? Go broke backing a loser?

I did some research and wrote a booklet on short selling in 1976. It’s now out of print, but not much has changed on the subject since then. In 2005, the booklet was the basis for a book titled How to Make Money Selling Short. The book was written with Gil Morales, who rewrote, revised, and updated my earlier work. Short selling is still a topic few investors understand and an endeavor at which even fewer succeed, so consider carefully whether it’s right for you. More active and seasoned investors might consider limited short selling. But I would want to keep the limit to 10% or 15% of available money, and most people probably shouldn’t do even that much. Furthermore, short selling is far more complicated than simply buying stocks, and most short sellers are run in and lose money.

What is short selling? Think of it as reversing the normal buy and sell process. In short selling, you sell a stock (instead of buying it)—even though you don’t own it and therefore must borrow it from your broker—in the hope that it will go down in price instead of up. If the stock falls in price as you expect, you can “cover your short position” by buying the stock in the open market at a lower price and pocket the difference as your profit. You would sell short if you think the market is going to drop substantially or a certain stock is ready to cave in. You sell the stock first, hoping to buy it back later at a lower price.

Sounds easy, right? Wrong. Short selling rarely works out well. Usually the stock that you sell short, expecting a colossal price decrease, will do the unexpected and begin to creep up in price. When it goes up, you lose money.

Effective short selling is usually done at the beginning of a new general market decline. This means you have to short based on the behavior of the daily market averages. This, in turn, requires the ability to (1) interpret the daily Dow, S&P 500, or Nasdaq indexes, as discussed in Chapter 9, and (2) select stocks that have had tremendous run-ups and have definitely topped out months earlier. In other words, your timing has to be flawless. You may be right, but if you’re too early, you can be forced to cover at a loss.

In selling short, you also have to minimize your risk by cutting your losses at 8%. Otherwise, the sky’s the limit, as your stock could have an unlimited price increase.

My first rule in short selling: don’t sell short during a bull market. Why fight the overall tide? But sooner or later you may disregard the advice in this book, try it for yourself, and find out the same hard way—just as you learn that “wet paint” signs usually mean what they say. In general, you should save the short selling for bear markets. Your odds will be a little better.

The second rule is: never sell short a stock with a small number of shares outstanding. It’s too easy for market makers and professionals to run up a thinly capitalized stock on you. This is called a “short squeeze” (meaning you could find yourself with a loss and be forced to cover by buying the stock back at a higher price), and when you’re in one, it doesn’t feel very good. It’s safer to short stocks that are trading an average daily volume of 5 to 10 million shares or more.

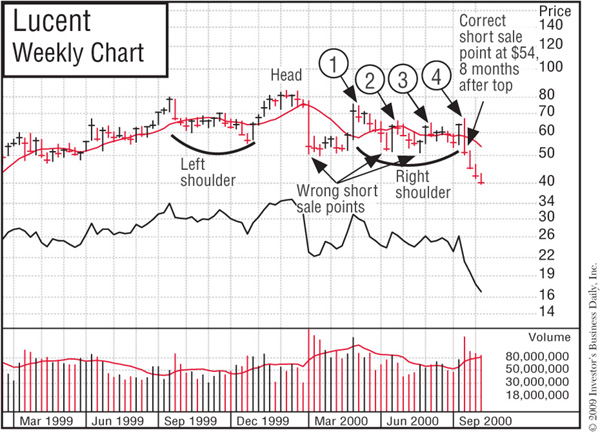

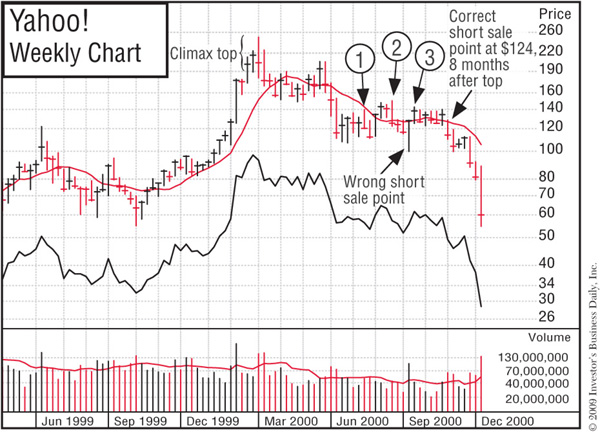

The two best chart price patterns for selling short are shown on the two graphs on page 288.

1. The “head-and-shoulders” top. The “right shoulder” of the price pattern on the stock chart must be slightly lower than the left. The correct time to short is when the third or fourth pullback up in price during the right shoulder is about over. (Note the four upward pullbacks in the right shoulder of the Lucent Technologies head-and-shoulders top.) One of these upward price pullbacks will reach slightly above the peak of a rally a few weeks back. This serves to run in the premature short sellers. Former big market leaders that have broken badly can have several upward price pullbacks of 20% to 40% from the stock’s low point in the right shoulder. The stock’s last run-up should cross over its moving average line. The right time to short is when the volume picks up as the stock reverses lower and breaks below its 10-week moving average line on volume but hasn’t yet broken to new low ground, at which point it is too late and then becomes too obvious and apparent to most traders. In some, but not all, cases, either there will be a deceleration in quarterly earnings growth or earnings will have actually turned down. The stock’s relative strength line should also be in a clear downtrend for at least 20 weeks up to 34 weeks. In fact, we found through research on model stocks over 50 years that almost all outstanding short-selling patterns occurred five to seven months after a formerly huge market leader has clearly topped.

John Wooden, the great UCLA basketball coach, used to tell his players, “It’s what you learn after you know it all that counts.” Well, one know-it-all investor wrote and told us that we obviously didn’t know what we were talking about, that no knowledgeable person would ever sell a stock short seven months after it had topped. Few people understand this, and most short sellers lose money because of premature, faulty, or overly obvious timing. Lucent at point 4 was in its eighth month and fell 89%. Yahoo! was in its eighth month after it had clearly topped, and it then fell 87%. Big egos in the stock market are very dangerous … because they lead you to think you know what you’re doing. The smarter you are, the more losses ego can create. Humility and respect for the market are more valuable traits.

2. Third- or fourth-stage cup-with-handle or other patterns that have definitely failed after attempted breakouts. The stock should be picking up trading volume and starting to break down below the “handle” area. (See Chapter 2 on chart reading and failed breakouts.)

For years, short selling had to be executed on an “uptick” from the previous trade. An uptick is any trade that is higher than the previous trade by at least a penny. (It used to be  or ¼ point or more up.) Therefore, orders should normally be entered either at the market or at a maximum, with a limit of $0.25 or so below the last price. A weak stock could trade down a point or more without having an uptick.

or ¼ point or more up.) Therefore, orders should normally be entered either at the market or at a maximum, with a limit of $0.25 or so below the last price. A weak stock could trade down a point or more without having an uptick.

After a careful study, the SEC recently rescinded the uptick rule. It should and probably will be reinstated at some point, with more than a penny price increase being required—perhaps a 10- or 20-cent rally. This should reduce volatility in some equities, especially in bad, panicky markets. The uptick rule was originally created in early 1937 after the market had broken seriously in the prior year. Its purpose was to require a  or ¼ of 1 point uptick, which would be 12½ or 25 cents, to slow down the uninterrupted hammering that a stock would be subject to during severe market breaks.

or ¼ of 1 point uptick, which would be 12½ or 25 cents, to slow down the uninterrupted hammering that a stock would be subject to during severe market breaks.

One alternative to selling short is buying put options, which don’t need an uptick to receive an executed trade. You could also short tracking indexes like the QQQs (Nasdaq 100), SMHs (semiconductors), or BBHs (biotech). These also do not require an uptick.

Shorting must be done in a margin account, so check with your broker to see if you can borrow the stock you want to sell short. Also, if the stock pays a dividend while you are short, you’ll have to pay the dividend to the person who owned the stock you borrowed and sold. Lesson: don’t short big dividend-paying stocks.

Short selling is treacherous even for professionals, and only the more able and daring should give it a try. One last warning: don’t short an advancing stock just because its price or the P/E ratio seems too high. You could be taken to the cleaners.

Options are an investment vehicle where you purchase rights (contracts) to buy (“call”) or sell (“put”) a stock, stock index, or commodity at a specified price before a specified future time, known as the option expiration date. Options are very speculative and involve substantially greater risks and price volatility than common stocks. Therefore, most investors should not buy or sell options. Winning investors should first learn how to minimize the investment risks they take, not increase them. After a person has proved that she is able to make money in common stocks and has sufficient investment understanding and actual experience, then the limited use of options could be intelligently considered.

Options are like making “all or nothing” bets. If you buy a three-month call option on McDonald’s, the premium you pay gives you the right to purchase 100 shares of MCD at a certain price at any time during the next three months. When you purchase calls, you expect the price of the stock to go up, so if a stock is currently trading at $120, you might buy a call at $125. If the stock rises to $150 after three months (and you have not sold your call option), you can exercise it and pocket the $25 profit less the premium you paid. Conversely, if three months go by and your stock is down and didn’t perform as expected, you would not exercise the option; it expires worthless, and you lose the premium you paid. As you might expect, puts are handled in a similar manner, except that you’re making a bet that the price of the stock will decrease instead of increase.

If you do consider options, you should definitely limit the percentage of your total portfolio committed to them. A prudent limit might be no more than 10% to 15%. You should also adopt a rule about where you intend to cut and limit all of your losses. The percentage will naturally have to be more than 8%, since options are much more volatile than stocks. If an option fluctuates three times as rapidly as the underlying stock, then perhaps 20% or 25% might be a possible absolute limit. On the profit side, you might consider adopting a rule that you’ll take many of your gains when they hit 50% to 75%.

Some aspects of options present challenges. Buying options whose price can be significantly influenced by supply and demand changes as a result of a thin or illiquid market for that particular option is problematic. Also problematic is the fact that options can be artificially and temporarily overpriced simply because of a short-lived increase in price volatility in the underlying stock or the general market.

When I buy options, which is rarely, I prefer to buy them for the most aggressive and outstanding stocks with the biggest earnings estimates, those where the premium you have to pay for the option is higher. Once again, you want options on the best stocks, not the cheapest. The secret to making money in options doesn’t have much to do with options. You have to analyze and be right on the selection and timing of the underlying stock. Therefore, you should apply your CAN SLIM system and select the best possible stock at the best possible time.

If you do this and you are right, the option will go up along with the stock, except that the option should move up much faster because of the leverage.

By buying only options on the best stocks, you also minimize slippage caused by illiquidity. (Slippage is the difference between the price you wanted to pay and the price you actually paid at the time the order was executed. The more liquid the stock, the less slippage you should experience.) With illiquid (small-capitalization) stocks, the slippage can be more severe, and this ultimately could cost you money. Buying options on lower-priced, illiquid stocks is similar to the carnival game where you’re trying to knock down all the milk bottles. The game may be rigged. Selling your options can be equally tricky in a thin (small-capitalization) stock.

In a major bear market, you might consider buying put options on certain individual stocks or on a major stock index like the S&P, along with selling shares of common stock short. The inability of your broker to borrow a stock may make selling short more difficult than buying a put. It is generally not wise to buy puts during a bull market. Why be a fish trying to swim upstream?

If you think a stock is going up and it’s the right time to buy, then buy it, or purchase a long-term option and place your order at the market. If it’s time to sell, sell at the market. Option markets are usually thinner and not as liquid as the markets for the underlying stock itself.

Many amateur option traders constantly place price limits on their orders. Once they get into the habit of placing limits, they are forever changing their price restraints as prices edge away from their limits. It is difficult to maintain sound judgment and perspective when you are worrying about changing your limits. In the end, you’ll get some executions after tremendous excess effort and frustration.

When you finally pick the big winner for the year, the one that will triple in price, you’ll lose out because you placed your order with a ¼-point limit below the actual market price. You never make big money in the stock market by eighths and quarters.

You could also lose your shirt if your security is in trouble and you fail to sell and get out because you put a price limit on your sell order. Your objective is to be right on the big moves, not on the minor fluctuations.

If you buy options, you’re better off with longer time periods, say, six months or so. This will minimize the chance your option will run out of time before your stock has had a chance to perform. Now that I’ve told you this, what do you think most investors do? Of course, they buy shorter-term option—30 to 90 days—because these options are cheaper and move faster in both directions, up and down!

The problem with short-term options is that you could be right on your stock, but the general market may slip into an intermediate correction, with the result that all stocks are down at the end of the short time period. You will then lose on all your options because of the general market. This is also why you should spread your option buying and option expiration dates over several different months.

One thing to keep in mind is that you should always keep your investments as simple as possible. Don’t let someone talk you into speculating in such seemingly sophisticated packages as strips, straddles, and spreads.

A strip is a form of conventional option that couples one call and two puts on the same security at the same exercise price with the same expiration date. The premium is less than it would be if the options were purchased separately.

A straddle can be either long or short. A long straddle is a long call and a long put on the same underlying security at the same exercise price and with the same expiration month. A short straddle is a short call and a short put on the same security at the same exercise price and with the same expiration month.

A spread is a purchase and sale of options with the same expiration dates.

It’s difficult enough to just pick a stock or an option that is going up. If you confuse the issue and start hedging (being both long and short at the same time), you could, believe it or not, wind up losing on both sides. For instance, if a stock goes up, you might be tempted to sell your put early to minimize the loss, and later find that the stock has turned downward and you’re losing money on your call. The reverse could also happen. It’s a dangerous psychological game that you should avoid.

Writing options is a completely different story from buying options. I am not overly impressed with the strategy of writing options on stocks.

A person who writes a call option receives a small fee or premium in return for giving someone else (the buyer) the right to “call” away and buy the stock from the writer at a specified price, up to a certain date. In a bull market, I would rather be a buyer of calls than a writer (seller) of calls. In bad markets, just stay out or go short.

The writer of calls pockets a small fee and is, in effect, usually locked in for the time period of the call. What if the stock you own and wrote the call against gets into trouble and plummets? The small fee won’t cover your loss. Of course, there are maneuvers the writer can take, such as buying a put to hedge and cover himself, but then the situation gets too complicated and the writer could get whipsawed back and forth.

What happens if the stock doubles? The writer gets the stock called away, and for a relatively small fee loses all chance for a major profit. Why take risks in stocks for only meager gains with no chance for large gains? This is not the reasoning you will hear from most people, but then again, what most people are saying and doing in the stock market isn’t usually worth knowing.

Writing “naked calls” is even more foolish, in my opinion. Naked call writers receive a fee for writing a call on a stock they do not own, so they are unprotected if the stock moves against them.

It’s possible that large investors who have trouble making decent returns on their portfolio may find some minor added value in writing short-term options on stocks that they own and feel are overpriced. However, I am always somewhat skeptical of new methods of making money that seem so easy. There are few free lunches in the stock market or in real estate.

Nasdaq stocks are not traded on a listed stock exchange but instead are traded through over-the-counter dealers. The over-the-counter dealer market has been enhanced in recent years by a wide range of ECNs (electronic communication networks), such as Instinet, SelectNet, Redibook, and Archipelago, which bring buyers and sellers together within each network, and through which orders can be routed and executed. The Nasdaq is a specialized field, and in many cases the stocks traded are those of newer, less-established companies. But now even NYSE firms have large Nasdaq operations. In addition, reforms during the 1990s have removed any lingering stigma that once dogged the Nasdaq.

There are usually hundreds of intriguing new growth stocks on the Nasdaq. It’s also the home of some of the biggest companies in the United States. You should definitely consider buying better-quality Nasdaq stocks that have institutional sponsorship and fit the CAN SLIM rules.

For maximum flexibility and safety, it’s vital that you maintain marketability in all your investments, regardless of whether they’re traded on the NYSE or on the Nasdaq. An institutional-quality common stock with larger average daily volume is one defense against an unruly market.

An initial public offering is a company’s first offering of stock to the public. I usually don’t recommend that investors purchase IPOs. There are several reasons for this.

Among the numerous IPOs that occur each year, there are a few outstanding ones. However, those that are outstanding are going to be in such hot demand by institutions (who get first crack at them) that if you are able to buy them at all, you may receive only a tiny allotment. Logic dictates that if you, as an individual investor, can acquire all the shares you want, they are possibly not worth having.

The Internet and some discount brokerages have made IPOs more accessible to individual investors, although some brokers place limits on your ability to sell soon after a company comes public. This is a dangerous position to be in, since you may not be able to get out when you want to. You may recall that during the IPO craze of 1999 and early 2000, there were some new stocks that rocketed on their first day or two of trading, only to collapse and never recover.

Many IPOs are deliberately underpriced and therefore shoot up on the first day of trading, but more than a few could be overpriced and drop.

Because IPOs have no trading history, you can’t be sure whether they’re overpriced. In most cases, this speculative area should be left to experienced institutional investors who have access to the necessary in-depth research and who are able to spread their new issue risks among many different equities.

This is not to say that you can’t purchase a new issue after the IPO when the stock is up in its infancy. Google should have been bought in mid-September 2004, in the fifth week after its new issue, when it made a new high at $114. The safest time to buy an IPO is on the breakout from its first correction and base-building area. Once a new issue has been trading in the market for one, two, or three months or more, you have valuable price and volume data that you can use to better judge the situation.

Within the broad list of new issues of the previous three months to three years, there are always standout companies with superior new products and excellent current and recent quarterly earnings and sales that you should consider. (Investor’s Business Daily’s “The New America” page explores most of them. Past articles on a company may be available.) CB Richard Ellis formed a perfect flat base after its IPO in the summer of 2004 and then rose 500%.

Experienced investors who understand correct selection and timing techniques should definitely consider buying new issues that show good positive earnings and exceptional sales growth, and also have formed sound price bases. They can be a great source of new ideas if they are dealt with in this fashion. Most big stock winners in recent years had an IPO at some point in the prior one to eight or ten years. Even so, new issues can be more volatile and occasionally suffer massive corrections during difficult bear markets. This usually happens after a period of wild excess in the IPO market, where any and every offering seems to be a “hot issue.” For example, the new issue booms that developed in the early 1960s and the beginning of 1983, as well as that in late 1999 and early 2000, were almost always followed by a bear market period.

Congress, at this writing in early 2009, should consider lowering the capital gains tax to create a powerful incentive for thousands of new entrepreneurs to start up innovative new companies. Our historical research proved that 80% of the stocks that had outstanding price performance and job creation in the 1980s and 1990s had been brought public in the prior eight to ten years, as mentioned earlier. America now badly needs a renewed flow of new companies to spark new inventions and new industries … and a stronger economy, millions more jobs, and millions more taxpayers. It has always paid for Washington to lower capital gains taxes. This will be needed to reignite the IPO market and the American economy after the economic collapse that the subprime real estate program and the credit crisis caused in 2008. I learned many years ago that if rates are raised, many investors will simply not sell their stock because they don’t want to pay the tax and then have significantly less money to reinvest. Washington can’t seem to understand this simple fact. Fewer people will sell their stocks, and the government will always get less revenue, not more. I’ve had many older, retired people tell me they will keep their stock until they die so they won’t have to pay the tax.

A convertible bond is one that you can exchange (convert) for another investment category, typically common stock, at a predetermined price. Convertible bonds provide a little higher income to the owner than the common stock typically does, along with the potential for some possible profits.

The theory goes that a convertible bond will rise almost as fast as the common stock rises, but will decline less during downturns. As so often happens with theories, the reality can be different. There is also a liquidity question to consider, since convertible bond markets may dry up during extremely difficult periods.

Sometimes investors are attracted to this medium because they can borrow heavily and leverage their commitment (obtain more buying power). This simply increases your risk. Excessive leverage can be dangerous, as Wall Street and Washington learned in 2008.

It is for these several reasons that I do not recommend that most investors buy convertible bonds. I have also never bought a corporate bond. They are poor inflation hedges, and, ironically, you can also lose a lot of money in the bond market if you make what ultimately turns out to be a higher-risk investment in stretching for a higher yield.

The typical investor should not use these investment vehicles (IRAs, 401(k) plans, and Keoghs excepted), the most common of which are municipal bonds. Overconcern about taxes can confuse and cloud investors’ normally sound judgment. Common sense should also tell you that if you invest in tax shelters, there is a much greater chance the IRS may decide to audit your tax return.

Don’t kid yourself. You can lose money in munis if you buy them at the wrong time or if the local or state government makes bad management decisions and gets into real financial trouble, which some of them have done in the past.

People who seek too many tax benefits or tax dodges frequently end up investing in questionable or risky ventures. The investment decision should always be considered first, with tax considerations a distant second.

This is America, where anyone who really works at it can become successful at saving and investing. Learn how to make a net profit and, when you do, be happy about it rather than complaining about having to pay taxes because you made a profit. Would you rather hold on until you have a loss so you have no tax to pay? Recognize at the start that Uncle Sam will always be your partner, and he will receive his normal share of your wages and investment gains.

I have never bought a tax-free security or a tax shelter. This has left me free to concentrate on finding the best investments possible. When these investments work out, I pay my taxes just like everybody else. Always remember … the U.S. system of freedom and opportunity is the greatest in the world. Learn to use, protect, and appreciate it.

Income stocks are stocks that have high and regular dividend yields, providing taxable income to the owner. These stocks are typically found in supposedly more conservative industries, such as utilities and banks. Most people should not buy common stocks for their dividends or income, yet many people do.

People think that income stocks are conservative and that you can just sit and hold them because you are getting your dividends. Talk to any investor who lost big on Continental Illinois Bank in 1984 when the stock plunged from $25 to $2, or on Bank of America when it crashed from $55 to $5 as of the beginning of 2009, or on the electric utilities caught up in the past with nuclear power plants. (Ironically, 17 major nations now get or for years have gotten more of their electricity from nuclear power plants than the United States does. France gets 78% of its electricity from nuclear power.)

Investors also got hurt when electric utilities nosedived in 1994, and the same was true when certain California utilities collapsed in 2001. In theory, income stocks should be safer, but don’t be lulled into believing that they can’t decline sharply. In 1999–2000, AT&T dropped from over $60 to below $20.

And how about the aforementioned Citigroup, the New York City bank that so many institutional investors owned? I don’t care how much it paid in dividends; if you owned Citigroup at $50 and watched it nosedive to $2, when it was in the process of going bankrupt until the government bailed it out, you lost an enormous amount of money. Incidentally, even if you do invest in income stocks, you should use charts. In October of 2007, Citigroup stock broke wide open on the largest volume month that it ever traded, so that even an amateur chartist could have recognized this and easily sold it in the $40s, avoiding a serious loss.

If you do buy income stocks, never strain to buy the highest dividend yield available. That will typically entail much greater risk and lower quality. Trying to get an extra 2% or 3% yield can significantly expose your capital to larger losses. That’s what a lot of Wall Street firms did in the real estate bubble, and look what happened to their investments. A company can also cut its dividends if its earnings per share are not adequately covering those payouts, leaving you without the income you expected to receive. This too has happened.

If you need income, my advice is to concentrate on the very best-quality stocks and simply withdraw 6% of your investments each year for living expenses. You could sell off a few shares and withdraw 1½% per quarter. Higher rates of withdrawal are not usually advisable, since in time they might lead to some depletion of your principal.

Warrants are an investment vehicle that allows you to purchase a specific amount of stock at a specific price. Sometimes warrants are good for a certain period of time, but it’s common for them not to have time limits. Many of them are cheap in price and therefore seem appealing.

However, most investors should shy away from low-priced warrants. This is another complex, specialized field that sounds fine in concept but that few investors truly understand. The real question comes down to whether the common stock is correct to buy. Most investors will be better off if they forget the field of warrants.

Merger candidates can often behave erratically, so I don’t recommend investing in them. Some merger candidates run up substantially in price on rumors of a possible sale, only to have the price drop suddenly when a potential deal falls through or other unforeseen circumstances occur. In other words, this can be a risky, volatile business, and it should generally be left to experienced professionals who specialize in this field. It is usually better to buy sound companies, based on your basic CAN SLIM evaluation, than to try to guess whether a company will be sold or merged with another.

Yes, the best foreign stocks have excellent potential when bought at the right time and right place, but I don’t suggest that you get heavily invested in them. The potential profit from a foreign stock should be a bit more than that from a standout U.S. company to justify the possible additional risk. For example, investors in foreign stocks must understand and follow the general market of the particular country involved. Sudden changes in that country’s interest rates, currency, or government policy might in one unexpected action, make your investment less attractive.

It isn’t essential for you to search out a lot of foreign stocks when there are more than 10,000 securities to select from in the United States. Many outstanding foreign stocks also trade in the United States, and many had excellent success in the past, including Baidu, Research In Motion, China Mobile, and América Móvil. I owned two of them in the 2003–2007 bull market. Several benefited from the worldwide wireless boom, but corrected 60% or more in the bear market that followed this bull move. There are also several mutual funds that excel in foreign securities.

As weak as our stock market was in 2008, many foreign markets declined even more. Baidu, a Chinese stock leader, dropped from $429 to $100. And the Russian market plummeted straight down from 16,291 to 3,237 once Putin invaded and intimidated the nation of Georgia.

The Canadian and Denver markets list many stocks that you can buy for only a few cents a share. I strongly advise that you avoid gambling in such cheap merchandise, because everything sells for what it’s worth. You get what you pay for.

These seemingly cheap securities are unduly speculative and extremely low in quality. The risk is much higher with them than with better-quality, higher-priced investments. The opportunity for questionable or unscrupulous promotional practices is also greater with penny stocks. I prefer not to buy any common stock that sells for below $15 per share, and so should you. Our extensive historical studies of 125 years of America’s super winners show that most of them broke out of chart bases between $30 and $50 a share.

Futures involve buying or selling a specific amount of a commodity, financial issue, or stock index at a specific price on a specific future date. Most futures fall into the categories of grains, precious metals, industrial metals, foods, meats, oils, woods, and fibers (known collectively as commodities); financial issues; and stock indexes. The financial group includes government T-bills and bonds, plus foreign currencies. One of the more active stock indexes traded is the S&P 100, better known by its ticker symbol OEX.

Large commercial concerns, such as Hershey, use the commodity market for “hedging.” For example, Hershey might lock in a current price by temporarily purchasing cocoa beans in May for December delivery, while arranging for a deal in the cash market.

It is probably best for most individual investors not to participate in the futures markets. Commodity futures are extremely volatile and much more speculative than most common stocks. It is not an arena for the inexperienced or small investor unless you want to gamble or lose money quickly.

However, once an investor has four or five years of experience and has unquestionably proven her ability to make money in common stocks, if she is strong of heart, she might consider investing in futures on a limited basis.

With futures, it is even more important that you be able to read and interpret charts. The chart price patterns in commodity prices are similar to those in individual stocks. Being aware of futures charts can also help stock investors evaluate changes in basic economic conditions in the country.

There are a relatively small number of futures that you can trade. Therefore, astute speculators can concentrate their analysis. The rules and terminology of futures trading are different, and the risk is far greater, so investors should definitely limit the proportion of their investment funds that they commit to futures. There are worrisome events involved in futures trading, such as “limit down” days, where a trader is not allowed to sell and cut a loss. Risk management (i.e., position size and cutting losses quickly) is never more important than when trading futures. You should also never risk more than 5% of your capital in any one futures position. There is an outside chance of getting stuck in a position that has a series of limit up or limit down days. Futures can be treacherous and devastating; you could definitely lose it all.

I have never bought commodity futures. I do not believe you can be a jack-of-all-trades. Learn just one field as completely as possible. There are thousands of stocks to choose from.

As you might surmise, I do not normally recommend investing in metals or precious stones.

Many of these investments have erratic histories. They were once promoted in an extremely aggressive fashion, with little protection afforded to the small investor. In addition, the dealer’s profit markup on these investments may be excessive. Furthermore, these investments do not pay interest or dividends.

There will always be periodic, significant run-ups in gold stocks caused by fears or panics brought about by potential problems in certain countries. A few gold companies may also be in their own cycle, like Barrick Gold was in the late 1980s and early 1990s. This type of commodity-oriented trading can be an emotional and unstable game, so I suggest care and caution. Small investments in such equities, however, can be very timely and reasonable at certain points.

Yes, at the right time and in the right place. I am convinced that most people should work toward being able to own a home by building a savings account and investing in common stocks or a growth-stock mutual fund. Home ownership has been a goal for most Americans. The ability over the years to obtain long-term borrowed money with only a small or reasonable down payment has created the leverage necessary to eventually make real estate investments possible for most Americans.

Real estate is a popular investment vehicle because it is fairly easy to understand and in certain areas can be highly profitable. About two-thirds of American families currently own their own homes. Time and leverage usually pay off. However, this is not always the case. People can and do lose money in real estate under many of the following realistic unfavorable conditions:

1. They make a poor initial selection by buying in an area that is slowly deteriorating or is not growing, or the area in which they’ve owned property for some time deteriorates.

2. They buy at inflated prices after several boom years and just before severe setbacks in the economy or in the particular geographic area in which they own real estate. This might occur if there are major industry layoffs or if an aircraft, auto, or steel plant that is an important mainstay of a local community closes.

3. They get themselves personally overextended, with real estate payments and other debts that are beyond their means, or they get into inviting but unwise variable-rate loans that could create difficult problems later, or they take out and live off of home equity—borrowing, rather than paying down their mortgage over time.

4. Their source of income is suddenly reduced by the loss of a job, or by an increase in rental vacancies should they own rental property.

5. They are hit by fires, floods, tornadoes, earthquakes, or other acts of nature.

People can also be hurt by well-meaning government policies and social programs that were not soundly thought through before being implemented, promoted, managed, operated, and overseen by the government. The subprime fiasco from 1995 to 2008 was caused by a good, well-intended government program that became incompetent, mismanaged, and messed up, with totally unexpected consequences that caused many of the very people the government hoped to help to lose their homes. It also caused huge unemployment as business contracted. In the greater Los Angeles area alone, many minority homeowners in San Bernardino, Riverside, and Santa Ana were dramatically hurt by foreclosures.

Basically, no one should ever buy a home unless he or she can come up with a down payment of at least 5%, 10%, or 20% on their own and has a relatively secure job. You need to earn and save toward your home-buying goal. And avoid variable-rate loans and smooth-talking salespeople who talk you into buying homes to “flip,” which exposes you to far more risk. And finally, don’t take out home equity loans that can put your home in a greater risk position. Also beware of getting into the terrible habit of using credit cards to run up big debts. That’s a bad habit that will hurt you for years.

You can make money and develop skill by learning about and concentrating on the correct buying and selling of high-quality growth-oriented equities rather than scattering your efforts among the myriad high-risk investment alternatives. As with all investments, do the necessary research before you make your decision. Remember, there’s no such thing as a risk-free investment. Don’t let anyone tell you there is. If something sounds too easy and good to be true, watch out! Buyer beware.

To summarize so far, diversification is good, but don’t overdiversify. Concentrate on a smaller list of well-selected stocks, and let the market help you determine how long each of them should be held. Using margin may be okay if you’re experienced, but it involves significant extra risk. Don’t sell short unless you know exactly what you’re doing. Be sure to learn to use charts to help with your selection and timing. Nasdaq is a good market for newer entrepreneurial companies, but options and futures have considerable risk and should be used only if you’re very experienced, and then they should be limited to a small percentage of your overall investments. Also be careful when investing in tax shelters and foreign stocks only traded in foreign markets.

It’s best to keep your investing simple and basic—high-quality, growth-oriented stocks, mutual funds, or real estate. But each is a specialty, and you need to educate yourself so that you’re not dependent solely on someone else for sound advice and investments.