INTRODUCTION

Life is hazardous. Survive the challenges of childhood and you enter adolescence, an endless flood of risks involving illegal substances and immoral temptations. Emerge from there to encounter uncertainty in your job and relationships, perhaps eventually adding the responsibility of protecting your own kids from the risks you managed to navigate around, if you were fortunate.

Then, as though compensating for the anticipated selective dysfunction of old age, the warm glow of retirement looms on the horizon, much of it funded by registered retirement savings plan (RRSP) contributions. It’s the end of the rainbow, a pot of gold unguarded by leprechauns and unsullied with the guilt of government handouts. It bears your name. It’s yours to spend. And when you step away from your job for the final time, it will be waiting for you.

You hope.

These days, projected pension benefits are as common as 10-cent beer and 50-cent pantyhose. Set aside those dreams of sailing the Mediterranean in June and walking warm beaches in January for a moment. Step over here and meet Retirement Reality, a slobbering beast with hairy earlobes, handing out debits for savings accounts, a nasty monster showing up on the doorsteps of too many ready-to-retire Canadians.

The Pension Plan You Always Wanted Is the One Others Are Enjoying

A generation ago, virtually all employers offered their workers a pension plan, usually promising defined benefits. This kind of plan determined a fixed amount paid each year through your retirement, employing a formula based on your income. Typically, your retirement income would represent 70 percent of the earnings you received during your final five years of work. Having shed many expenses of your working years, such as mortgage payments, commuting costs, your kids’ budgets, and other drains on your income, and qualifying for various tax breaks and government handouts to be added to your bank account, this was likely to be an adequate amount. With a little planning, you could anticipate a lifestyle close to the one you had when you were rising with the sun each morning, gnashing your teeth at the boss all day, and dreaming about retirement at night.

Defined-benefit pensions were a product of the Age of Innocence—meaning pre-1980, when large corporations such as Northern Telecom (Nortel), Massey-Ferguson, General Motors, Canadian Pacific, and others were expected to keep operating forever, or at least over the lifetimes of their pensioned employees.

My, how things have changed. Many of those companies have vanished; the rest are feeble and struggling. And while the corporations promising the defined-benefit pensions are becoming extinct, the rest of us are living far longer than the designers of those old-style pensions expected. What was once reasonable for companies to provide for their retirees now appears impossible because the nest egg is being tapped longer than planned. To make things worse, many of the companies that are committed to these plans, if they’re still around, employ fewer people to generate the profits needed to keep the money flowing. General Motors, it’s rumoured, has five retirees receiving pensions for every worker building its cars, explaining one of several reasons why automotive companies have practically run off the road entirely.

Couldn’t the actuaries who plot this kind of stuff see the problem coming? Apparently not. Nor could the unions, which kept pushing for defined-benefit pensions. During periods when companies were generating surpluses in their pension assets, union leaders demanded that benefits be raised to match the increase, yet when things turned sour, the unions insisted that benefits not be reduced.

Even fortunate Canadians who remain employed by firms offering defined-benefit plans have been shaken by the credit crisis. Domtar’s pension managers, for example, purchased $445 million in Asset-Backed Commercial Paper (ABCP) in 2006–2007, much of it based on the sub-prime mortgages that triggered the sinking of the global economy in 2008–2009. These investments represented a whopping 30 percent of the total pension fund assets recorded at the end of 2007. By February 2009, Domtar’s pension fund had written off almost $200 million, suggesting the company will have to lower pension payments and raise employee contributions to honour its commitment to retirees.*

This is not an unusual situation. At the beginning of 2008, Canadian companies with defined-benefit plans reportedly had sufficient cash to cover 96 percent of their pension obligations— money that would be available even if the companies declared bankruptcy. One year later, these same firms harboured less than 70 percent of the money needed to cover the same obligations.†

Companies that are still around and solvent avoid definedbenefit plans, where employees are told, “Here’s what you get when you leave.” They have switched to defined-contribution plans, where retirees are basically advised, “Work it out on your own and remember to close the door when you leave”—the only way for employers to avoid the long-term obligations of defined-benefit programs that, in the private sector, are a dying breed.

Working Seven Years Longer before Saying “Adios!”

About the only workers enjoying defined-benefit pension plans these days are government employees, who glide from the womb of public-service job security to the warm lap of a lifelong income that reflects salary levels achieved during their years of highest earnings. Unlike almost all workers in the private sector, publicservice employees don’t mess around with the Retirement Lottery, hoping to make the correct investment decisions and aiming for some unpredictable asset level when they retire. It’s there for them to collect when they end their working years: a fixed amount linked to their working income, making the transition from labourer to loafer as smooth as stepping off an escalator.

While you’re grumbling over that fact because you’re selfemployed or work for a company with defined-contribution pensions, chew on this: A 2008 Treasury Board study determined that federal public servants in Canada pay a mere 28 percent of the service costs to manage their pension plans. You, however, pay 100 percent of the same cost while picking up almost three-quarters of the expense of ensuring those other people receive the benefits to which they’re entitled.

If you are employed in the federal public service, your retirement savings are protected behind a high and impregnable wall and your income is predetermined and guaranteed, so you may feel you don’t need this book. You’re welcome, however, to stick around and see how the rest of us need to build and protect our retirement savings. Of course, if you have investments outside a pension plan, either registered within an RRSP or registered retirement income fund (RRIF), you’ll find plenty of valuable information to safeguard your portfolio on the following pages. This book is specifically directed, however, at the many Canadians who, when it comes to retirement income planning, are like the first little pig in the fairy tale, huddling within a house of straw that may collapse with the first strong puff from a passing wolf.

Knowing how Canadians employed in the public service enjoy a defined-benefit pension plan, are you surprised to learn they retire at the average age of 59—versus the rest of us, who typically work until we’re 66 years old? Wouldn’t you like an extra seven years of a guaranteed income to cover your green fees, travel costs, and hammocks?

The Risk Is All Yours. But the Profits Aren’t.

Think of comfortable retirement as a vacation destination, a place to enjoy walks on the beach, play some afternoon golf, do a little fishing, find time for a little card playing, and sample a whole bunch of relaxation. Now: How do you get there?

People with traditional defined-benefit pensions let others do the driving. They rarely worry about bad weather, detours, toll roads, and other travel hazards, which are the concern of whoever is sitting up front and doing the driving. Defined-benefit pension people travel the route to retirement unconcerned about trading costs, rates of return, and asset allocation, not to mention greedy financial advisors and fraud artists.

You, however, are behind the wheel of your own pension plan, probably an RRSP. You can hire a chauffeur to choose the route and speed, avoid the bumps, and drive you safely to your destination, but chauffeurs cost money. You could drive yourself, except you don’t know the route. Even more serious, you probably don’t know how to drive.

This travel analogy is simplified but appropriate because more of us are finding ourselves in charge of something we don’t know how to operate—in this case, a complex, long-term investment. The knowledge quotient varies, but it remains abysmally low.

Before the credit crisis of 2008–2009, the asset values of some RRSPs exceeded $1 million, yet many of their owners had no idea how to define a mutual fund, how to measure (or even define) a management expense ratio (MER),*how to handle asset allocation, and how to protect themselves against a repeat of the severe collapse suffered by their portfolios in 2008 and 2009.

These were the lucky ones. They employed qualified financial guides and earned enough income to make substantial contributions to the plan over several years. Of course, a million dollars doesn’t buy all that it used to, but all those zeros in their accounts make retirement a little more fun and a lot less worrisome. Permit me, however, to ask three totally valid, and somewhat cynical, questions:

1 How much more could they have accrued over the same period, making the same contributions, if they had cut their investment expenses by even 1 percent annually? Losing 2 or 3 percent each passing year to excessive fees may not sound like much, but over time it can reduce the potential growth of an RRSP by half. Which would you rather have in your RRSP account when you retire—$1 million or $2 million?

2 How much did these holders of $1 million RRSPs lose to incompetent or self-interested advice from sources more interested in lining their own pockets than in building their clients’ assets? Perhaps 90 percent of all RRSP/RRIF transactions are conducted by licensed professionals whose income level is determined almost exclusively by the commissions earned from those same transactions. Other professions use the same method of remuneration, of course. Like used-car salespeople.

3 How well were these RRSP investors protected against catastrophic losses during the credit crisis of 2008–2009? RRSP owners need to shield their savings against losses as they approach retirement age. A simple, easy-to-implement technique can be applied to create this protection, but few advisors employ it.

This last point represents one of the most unassailable criticisms of the investment industry, in my opinion. Comprising brokers, financial advisors, mutual fund salespeople, and countless behindthe-scenes individuals and corporations, the investment industry promotes itself as dedicated to helping clients reach their financial and investment goals. In the case of RRSP and many Tax-Free Savings Account (TFSA) investors, this means both building and protecting their assets over the long term.

The protection aspect is critical (and the basis of this book) because the performance of stocks and bonds varies widely. Or, as advisors frequently shrug when clients complain about substantial losses in their account: “The markets go up and the markets go down.”

Precisely. Unfortunately, too many financial advisors respond to this axiom like dogs on a Ferris wheel, wagging their tales in ecstasy as things rise and grabbing a quick nap as they descend.

It is nonsense for anyone in the industry to plead ignorance (“We didn’t see it coming!”) about the emergence of a bear market, including the one that savaged the assets of RRSP investors in 2008–2009. Did they, as investment professionals, honestly believe markets relentlessly rise toward infinity? Every licensed securities advisor knows that markets ebb and flow. The amplitude and schedule of cycles may be indeterminate, but they occur as surely as the passage of the sun across the sky each day. Too many advisors are driven by a system that encourages investors to purchase and hold expensive mutual funds, generating fat commissions and fees for advisors while returning unimpressive earnings for investors.

The commission-based remuneration system for advisors remains at the heart of most investor concerns. Think of it for a moment: Would you entrust your health to a physician whose income was earned from commissions on the pharmaceuticals he or she prescribed for you?

A few financial advisors will (and already have, based on responses to previous books) cry that I’m being unfair about their livelihood. They fail to receive reasonable credit for building portfolios when markets are rising, they’ll whine, but everyone is prepared to jump on them when losses occur. “Clients don’t complain when their accounts are rising in value, only when they fall!” they grumble. Which is like saying a leaky roof is fine on a sunny day because it only needs to work when rain falls. A roof’s primary purpose is to protect the resident against the elements. And a financial advisor’s role is to see that the investment fund grows, not shrinks, over time.

The advisor complaints are specious. More than that, they are insulting. During the bull market of 2003 to 2006, a dart-throwing monkey could have picked stocks and mutual funds that made money. Canadians investing for their retirement years need more than someone who collects commissions and fees when the markets soar; they need someone who truly gives a damn when the markets plunge, as markets inevitably do from time to time.

Investors suffer a severe disconnect between their concept of a financial advisor’s role and the industry’s actions. The vast majority of Canadians expect financial advisors to play the role of fiduciary, a heavyweight term meaning someone who holds someone else’s property in trust. “In trust” connotes not merely having possession of a property but caring for it to the benefit of its actual owner. Yet the industry, regardless of its protestations through various channels, regards advisors as merely licensed salespersons, and fights with tooth and nail any claim that its actions involve a fiduciary role.

Everyone who relies upon services rewarded via commissions or fees to a financial advisor has an expectation that their advisor will pay as much attention to the preservation of capital as to its acquisition. When the investor’s age is 50-plus years and the portfolio’s value is in six figures, it should be more than an expectation: It should be an unchallenged right.

Advice based on an advisor’s self-interest or derived from outright incompetence is the most common cause of unnecessary investor losses, but other disasters can occur, of course. Like fraud, embezzlement, and theft.

Bank Robbery Is Hard Work Compared with Investment Fraud

With absolutely no intention of planting larcenous ideas in your mind, here’s something you should know: The easiest way to get your hands on other people’s money with the least chance of being caught, and even less chance of receiving a long jail term, is through investment fraud aimed at RRSP owners who are 50 or older.

White-collar crime in Canada often appears to be treated as a victimless event by our courts and justice system. Theft that would slap you in a grey-bar hotel for 20 or 30 years if committed in the United States usually earns you a few months in a minimum-security establishment in Canada. If it’s your first offence and no physical injury was inflicted, your incarceration period is reduced by fivesixths. Which means that if you receive a six-year sentence for your crimes, you’ll spend a year playing chess and watching TV before being back on the street—initially in a halfway house for a few months and eventually regaling your buddies at the neighbourhood bar with tales of life in the big house. Assuming, of course, that your buddies do not include the people you defrauded in the first place.

Exaggeration? Consider these examples:

BRE-X. One of the world’s largest mining scandals, the Bre-X fraud robbed trusting investors of an estimated $300 million. After an investigation extending for more than two years, not one criminal charge was laid. The Ontario Securities Commission brought charges of insider trading against a single key player in 2001. Six years later, without even making an appearance in court, this sole defendant was acquitted.

IAN THOW. The senior vice-president of Berkshire Investments flew his private corporate jet around the world, drank 100-year-old Scotch whisky at $10,000 per bottle, and flaunted the high life to Canadians who entrusted him with their money. He lived in luxury near Portland, Oregon, while his former clients, many of whom alleged that their retirement savings had been wiped out, fumed for years. Thow was arrested in February 2009 and charged with defrauding clients of $32 million.

DAVID BLOW. Convicted of fraud from a previous scheme, Blow convinced members of his church congregation to invest $6.5 million of their retirement funds with him. None of the money was recovered. Despite his record, Blow received a sentence of three and a half years in prison and was released after serving eight months.

SALIM DAMJI. Damji defrauded Islamic communities in Canada and elsewhere of as much as $100 million, spending all but $5 million of it on gambling and bad investments. Sentenced to seven and a half years in prison, Damji astonished his victims less than 18 months later when he strolled casually among them in his old Toronto neighbourhood, released on day parole.

EARL JONES. Jones was arrested in July 2009 and charged with multiple counts of fraud and theft totalling as much as $50 million, money that had been entrusted to him by 150 investors. Many of his clients were elderly residents of nursing homes and hospitals. Jones and his wife, according to investigators, lived well while it lasted, burning their way through $50,000 of investors’ money each month. The only surprise in this tale is that Jones was allegedly never licensed by the province of Quebec. He called himself a financial advisor and people believed him.

These scoundrels and others like them prey on their victims’ trust, something that people older than 50 years of age tend to possess in greater amounts than the younger set. Lacking the cynicism of Generation X, older folk trust that another person’s word is their bond and want to believe that everyone maintains the same high moral standard as their own. Once they have built a nest egg over 30 or 40 years of work, they cannot believe that someone they trust will walk away with it. When this happens, the victims expect a) to recover their losses, and b) to see the perpetrators pay for their crimes with punishment that includes several years behind bars. That would be fair; sadly, fair is rare.

And Then, Of Course, There’s the Odd Global Economic Meltdown

Even if you manage to make good investment decisions, minimize costs associated with your portfolio, and avoid jackals determined to snack on your hard-earned retirement savings, you cannot avoid feeling the force of financial disasters such as the one that shook the world’s confidence in late 2008.

Periodic slides in stock-market values are known as corrections, a term that recalls images of a teacher marking your grade four spelling test. Every couple of decades, something akin to the most recent calamity occurs despite assurances that all is well—the claim supported by assurances that “The economy is in great shape!” and “Things have never been better!” usually uttered by smiling politicians.*

You may have watched the innards of your own RRSP, RRIF, or TFSA portfolio being ripped to shreds by the 2008–2009 event known variously as the Great Recession, the New Depression, the Credit Crisis, and the “What-the-hell-happened?” incident. Since about 1990, while you were diligently adding to your retirement savings portfolio through the fruits of your daily labour, other folks were earning multi-million-dollar salaries and bonuses by selling financial sows’ ears as investment silk purses.

Here are two things to count on: The financial conjurors behind those shenanigans are not at all worried about damage to their retirement nest eggs, unless it means cutting back on the number of yachts they plan to own; and similar events of varying scope and origin will occur again in coming years, each of them deflating the value of your retirement savings.

The closer you move toward retirement, the more harrowing these disruptions become. Grumbling about the unfairness of market manipulators, charlatans, and fraud artists will do nothing to restore your assets, and by the time your portfolio feels the impact of their hijinks, the damage will have been done.

Unless your entire RRSP or RRIF is in savings accounts under the protection of the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (CDIC), with each account totalling less than $100,000, do not expect anyone to replace losses suffered as a result of actions committed by others, whether they are brokers who “churn” (create excess buying and selling activity) your account to build commissions, advisors who funnel your funds into pipelines leading to their own pockets, or sociopathic embezzlers who prey on your misplaced trust. You may, with time, recover a portion of your losses via civil and criminal action against such malfeasance. You may also win this weekend’s lottery. Counting on either is like planting onions in the fall and hoping for tulips in the spring.

The Best Way to Deal with Unfairness, Ill Fortune, and Poor Timing Is to

Prepare for Them

Among the most hallowed rules for Canadian RRSP investors over several years was the maxim buy and hold, carved into granite by gurus such as Warren Buffett. The system was simple to follow, if somewhat more difficult to execute: Buy shares in quality companies. Ignore fluctuations in stock prices, international crises, bonds and GICs, technological innovations, and unfolding events. Hold them until either you or your heirs need the money. Just get into the market carefully and stay there.

Investors who heeded this advice at the beginning of the new millennium have a right to assume that Buffett and his disciples have all the investment acumen of tree stumps. See for yourself:

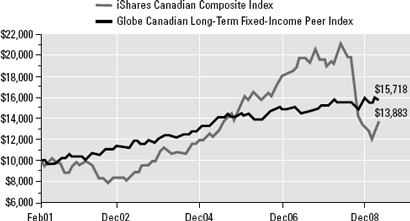

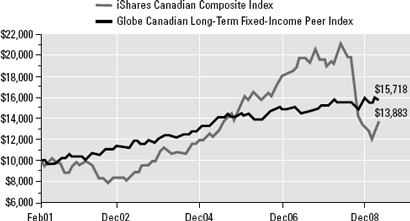

SOURCE: www.globeinvestor.com. Used with permission

The dark line traces returns over the period from February 2001 to May 2009, comparing the performance of a popular exchange traded fund* with that of long-term bonds over the same period. While the three-year period from June 2005 to June 2008 delivered spectacular returns, that’s only one-third of the period in question; for two-thirds of the time, you would have earned more from boring long-term bonds, the basis of the Long-Term Fixed Income Peer Index. Bonds are not the equities favoured by Buffett and most financial advisors. Bonds issued by federal and provincial governments in Canada are guaranteed; what you see on the paper is what you get paid on a fixed date.

Buy-and-hold proponents will note that shifting the time period a few months either way would show a different picture, likely favouring stocks. They would be correct. But faced with a fixed date, such as retirement, you lack the ability to do broad timeshifting. More to the point, this negates to at least some degree the near-universal faith in buy and hold as the ultimate investing philosophy. The closer you move toward retirement, the less you can tolerate the wild swing in stock prices known as volatility. Volatility in your RRSP is like the wilder escapades of your youth. Back then, you could tolerate it. In middle age and beyond, you should avoid it.

This book was prepared to assist you in equipping your investment portfolio with protection against attacks on your savings that are likely, or at least possible, including excessive volatility, inflation, high commissions and fees, outright fraud, and various other avoidable risks.

The techniques and suggestions provided here function similarly to the seatbelts and airbags in your car: They may not ensure that you escape injury entirely, but they sure improve your chances of survival.

*Canadian Centre for Ethics and Corporate Policy, The Canadian Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Crisis, March 26, 2009, p. 12.

†Kristine Owram, The Canadian Press, Struggling Pension Plans Call on Government to Relax Funding Rules, January 11, 2009.

*The management expense ratio (MER) is the amount of money expressed as a percentage of the mutual fund’s total assets, removed from the fund annually as the management fee.

*For my take on the 2008 credit crisis, check out Bubbles, Bankers & Bailouts (D&M Publishers, 2009).

*For definitions of exchange traded funds and other investment terms, please consult the Glossary on page 179.