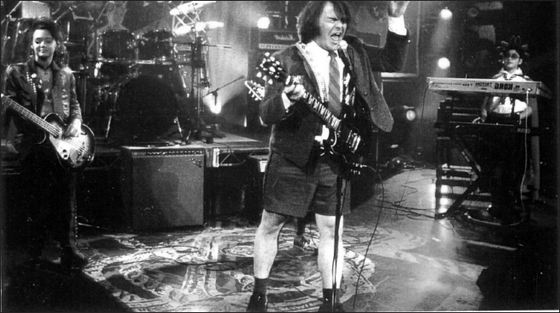

Revellers in Linklater’s

Dazed and Confused kidnap bronze figures playing pipe and drum from a memorial to the American War of Independence and paint their faces black and white to resemble members of KISS, an American rock band of the 1970s whose image was based on this carnivalesque trademark. Strapped to the back of a truck and adorned with fireworks, they are a monument to irreverence in the midst of the Moon Tower keg party that commemorates the last day of school in May 1976.

1 However, by 1983 KISS had abandoned their face paint to seek credibility. It was not until 1996 that nostalgia prompted their reunion with reinstated make-up and a worldwide concert tour. But which of these incarnations might be taken as most representative of the cinema of Richard Linklater? Is it the original monument to American independence or the witty but vandalistic imitation? Is it a cinema that wears a youthful disguise or one that doffs it in order to gain credibility for maturing expression? Or is it all of the above? Answers may be found by an exploration of the contradictions in his cinema. Is Linklater an independent auteur or a collaborator in search of industry? Is he a director favouring original screenplays and improvisation or one dependent upon adaptable works and rehearsal? Do his films reflect an American sense or a European sensibility? Are they political or indifferent? Is he a Modernist or a Postmodernist filmmaker? Or, again, is he all of the above, making dazed and confused the most appropriate response to his cinema?

Contradictions arise when attempting to assess the cinema of Linklater largely because his emphasis on collaboration undercuts any semblance of the kind of performative auteurism that posits the director as ‘primary creator’ during production. The possibility and pretence of a film director being somehow gifted to fashion films as ideological constructs that revel and reveal themselves in their own quirks, codes, conventions and signifiers is a common obstacle to complete appraisals of the invention, construction and reception of films. Yet it is the structuring process of filmmaking rather than the construction of any monument to its meaning that most consumes Linklater. Developing projects, negotiating funding, corralling collaborators, encouraging actors, promoting talent and hawking for distribution before moving on to the next project is what typifies his career, with the composite role of producer increasingly commanding most of his energy. Neither exclusively independent nor wholly dependent upon studios and distributors, Linklater’s career must be plotted with an entire arsenal of sliding scales that includes the one that major studios use to calibrate film budgets ranging from those that are appropriate to the absolute autonomy of filmmakers whose talents suit a narrow marketing strategy to those that factor in the servitude of those whose skills can be applied to industrial franchises. Such calculations are exacting since few high-stakes gambles have been placed on contemporary American filmmakers by a major studio since the profligacy of the 1970’s movie brats unless their boast of a marketable vision can be backed up by past grosses, the loyalty of box-office stars and a record of profitably pushing but never bankruptingly breaking generic formulas. Perhaps only the careers of David Fincher, Michael Mann and Christopher Nolan have begun to meet these criteria sufficiently, whereas other filmmakers who have emerged from the independent sector have seen their talents siphoned away from small, personal projects to add flavour to the industrial formula for superheroes.

2 Linklater seems unlikely to helm an episode in any supersized franchise any time soon, however, for he has mostly tried to skew the scale towards the privilege of autonomy that comes with low-budget filmmaking. Even with studio projects such as

Dazed and Confused and

The School of Rock there is a degree of independence to be found and/or fought for over their small-to-average studio budgets. On the other hand, any deal demands some respect for the investment and a consequent responsibility to the investor, which means that creative independence is arguably incompatible with an industry where a director is part of a manufacturing process. Contradictions thus arise because this also suggests that the kind of collaboration that Linklater most often seeks might actually be best found on a studio production. From the viewpoint of the filmmaker as well as the studio, the negotiation of financing and facilities for production and distribution makes independence something measurable in the kind of fractions that Linklater has agreed to with varying degrees of success and subversion.

In his working methods and practices Linklater actually opposes the notion of auteurism that Andrew Sarris introduced to America in his essay ‘Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962’ (1962) as a structuring principle of enunciation that supported the concept of the authentically creative filmmaker at work within the studio system. This ‘auteur theory’ was also ‘a surreptitiously nationalist instrument for asserting the superiority of American cinema’ (Stam 2000: 89); for it was by adopting auteurism as a structural conceit and marketing tool respectively that critics and Hollywood somewhat displaced European cinema as the normative reference for the study and appreciation of film. At the same time, the structuralist basis of film criticism in the 1960s and 1970s empowered dissections of the work of directors such as Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks and extended this courtesy to many lesser-known and contemporary directors. Critics sought the traits and building blocks of any director’s supposedly singular vision and thereby elevated the likes of Michael Cimino, Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola to positions of indulged despotism within the major studios. Celebrating these filmmakers as auteurs was a critical construct that fed an academic need for structure, a critical need for recognition, studios’ marketing strategies, directors’ egos and the increasing public interest in celebrity. Despite correctives from critics such as Pauline Kael and numerous academics, however, auteurism survived to resemble a populist championing of the voice of the director as the sole point of enduring stability amongst so much rupture, fragmentation and change in a multimedia world. Thus an emblematic film such as

Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994) erected a matrix that ‘suggests that every text forms an intersection of textual surfaces’ (Stam 2000: 201).

Pulp Fiction by which Tarantino duly dazzles with a glut of references that correspond to the multi-dimensional space that Roland Barthes described when a ‘variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash’ (1982: 146). In

Revolution in Poetic Language (1984), however, Julia Kristeva analysed intertextuality as ‘the passage from one sign system to another’ (1984: 59) and invoked the destruction of the old system and the flourishing of the new, while nonetheless maintaining an awareness of overlapping meanings in which the new system might use the same signifiers as the old one. It is in these terms, for example, that

Slacker may be understood as a palimpsest, as a renewal and subversive application of Bakhtin’s notion of carnival, which he posits as a social institution in which distinct individual voices interact. The film’s respectful embodiment of carnival means that it avoids the traps of both pastiche and allegory and its polyphony remains true to the members of a community that made this film about itself instead.

Linklater is just one member of this community, of course, and as such must be recognised as an example of what Bakhtin posited as an unfinalisable self; that is, a person who cannot ever be completely known, understood or labelled. This overlaps with the theories of Henri Bergson (1992b), who wrote of an eternal becoming because it sees in people the eternal potential for change. However, in his writing on

Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics (1984b [1929]), Bakhtin also notes the influence of everyone on everyone else and therefore denies the possibility of isolation while simultaneously recognising creative works as representations of this polyphony, that is, of the many voices that go into creating a work or a person. This concept underpins the open auditions held for

Slacker and

Dazed and Confused, for instance, as well as the casting of people and their empathetic animators for

Waking Life in which Timothy ‘Speed’ Levitch as Himself informs Main Character that their lives are ‘adaptations of Dostoevsky novels starring clowns’. It also points to the incorporation of actors’ own personalities in characters such as Jesse and Céline, Dewey Finn and the kids who play-acted in

The School of Rock and

Bad News Bears. Just as each distinct character in

Slacker may speak for an individual self (including Linklater as Should Have Stayed at Bus Station), so the resultant film is an unfinished monument to the evolving community of voices, each of which carries its own truth, with which all-comers interact. Within this polyphony may ‘also figure, but in far from first place, the philosophical views of the author himself’ (Bakhtin 1984b: 5), which suggests that Linklater’s relation to a work such as

Slacker corresponds to how Bakhtin perceives of Dostoevsky:

A plurality of independent and unmerged voices and consciousnesses, a genuine polyphony of fully valid voices is in fact the chief characteristic of Dostoevsky’s novels. What unfolds in his works is not a multitude of characters and fates in a single objective world, illuminated by a single authorial consciousness; rather a plurality of consciousnesses, with equal rights and each with its own world, combine but are not merged in the unity of the event. (1984b: 6; emphasis in original)

For example, a character such as Dostoyevsky Wannabe (Brecht Andersch) in Slacker is worked up in writing and rehearsal and embellished in performance with the result that it possesses extraordinary independence in the structure of the work; it sounds, as it were, alongside the author’s word and in a special way combines both with it and with the full and equally valid voices of other characters’ (Bakhtin 1984b: 7; emphasis in original). The study of film as an academic discipline may have benefitted from a belief in a director’s creative artistry because it empowered critics, academics and filmmakers to raise the status of cinema to that of other arts, but in the cinema of Linklater, as for the novels of Dostoevsky, ‘the direct and fully weighted signifying power of the characters’ words destroys the monologic plane’ (Bakhtin 1984b: 5). Nevertheless, in addition to considerations of the economic viability of Linklater’s career, his working practice in relation to studios and collaborators (including co-writers), his association (whether real or assumed) with contemporary filmmakers, the marketing of the films he has directed and, following Timothy Corrigan (1991), the commercial performance of auteurism (particularly in the context of it being so enthusiastically performed by several of his contemporaries), the cinema of Linklater must also be contextualised within World cinema and in relation to key influences such as Bresson and Godard. By these means may be plotted a schema of aesthetic development and its relation to political and philosophical thought and meaning.

Should have, could have, would have stayed at the bus station; but

Slacker was made with $23,000 of Linklater’s own money, grants and deferrals and was picked up for distribution by Orion Classics, while

Dazed and Confused was a studio production that came in at $6 million for Universal. On it Linklater learnt that if a filmmaker seeks some degree of independence the film’s price must be low, which he subsequently forgot on

The Newton Boys, which was made for $27 million from the Twentieth Century Fox Corporation. Balancing the scale between independence and studio interference,

Before Sunrise, SubUrbia and

Before Sunset had Castle Rock Entertainment as intermediary between them and distributor Columbia Pictures; but

The School of Rock was made for $35 million for Paramount, while

Bad News Bears cost $30 million to produce and was locked into a distribution deal with Paramount and UIP. The variety of production deals and packages points to a volatile but versatile industry, although the piecemeal accumulation of independent funding as was the case with

Fast Food Nation can prove as much of a challenge as distribution. The risk is such that the montage of funding required to attach a green light to any project is fraught with a collage of clauses. For all its period detail,

Me and Orson Welles cost in the low $20 million range, for instance, but much of this came from The Isle of Man Development Fund on condition that the production was completion bonded, ‘at least 50 per cent of all principal photography [took] place on the island [and] at least the equivalent of 20 per cent of the below the line budget [was spent] with local service providers’ (Anon. 2009e).

Me and Orson Welles was duly filmed in large part at the Gaiety Theatre in the island’s capital, Douglas, but only after Linklater had submitted an application for funding that contained (as per conditions and criteria) a fully developed shooting script, a detailed synopsis, a biography and filmography of all key elements, including principal cast, producers, writer and director, and a ‘proposed finance structure including principal conditions attached to all third party investment and projected budget [and proof of] some initial finance already in place’ (ibid.). And upon completion it faced perhaps the greatest risk run by independently produced features, that of failing to secure distribution beyond festivals.

After a career spanning thirty years, as of May 2009 Linklater’s career gross in America stood at $155,714,563 which was massively skewed by $81,261,177 from The School of Rock (Anon. 2009f). The remaining $75 million gave an average $5.7 million gross in the USA for the remaining features, putting only a few into domestic profit. Starting out, Slacker made $1.2 million and Dazed and Confused struggled just past break-even to $7.9 million. The Newton Boys made back only $10 million of its $27 million, Waking Life made $3 million, Bad News Bears barely covered its budget and Fast Food Nation scraped just $1 million. Nothing on Linklater’s spreadsheet besides The School of Rock could ever excite a major studio such as Paramount, which duly showed interest in signing Linklater, writer Mike White and star Jack Black to make a sequel called The School of Rock 2: America Rocks that, says Linklater, ‘Mike White was writing […] a long time ago, but it’s become dormant’ (in Buchanan 2009). Yet this same CV does attest to Linklater’s longevity at the low-cost level of American filmmaking, as well as the possible viability of regional filmmaking. It also indicates how important ‘independent’ American cinema’s reception abroad is, for the aforementioned figures do not include international box office, where, for example, the $17.2 million gross of Before Sunrise is three times the domestic box office of $5.4m. In addition, the total gross for this film indicates a $20 million profit or an 800 per cent ratio of return on its $2.5 million budget. For comparison’s sake, to achieve the same return on each dollar a blockbuster like Star Trek (J. J. Abrams, 2009) would have to earn $1.2 billion on its budget of $ 150 million. Moreover, the cult followings that make the likes of Criterion Collection DVD editions of Slacker and Dazed and Confused worthwhile also point to enduring critical, academic and popular interest in Linklater as well as the importance of the home viewing audience, ancillary markets and other evolving ways of disseminating films to the kind of fan base whose enthusiasm makes Before Sunrise the lowest-grossing film to ever spawn a sequel.

Survival is its own form of success, however, and Linklater has always claimed extra lives by pinballing from project to project with a collaborative ethos, breaking even and the chance to make another film seemingly ambition enough. The negotiation of the degree of autonomy necessary for the collaborative creative process to prosper is a cornerstone of his career, although the notion that this is primarily an auteurist objective is unrealistic. His reputation as an independent filmmaker endures because of the resonance of the emblematic

Slacker and the kindred spirit of a succession of protagonists in his ensuing films rather than any refusal to work with the studios. Says Linklater:

I love the studio system. I would like to have been Vincente Minnelli or Howard Hawks making a film or two a year in the studio system. But you know, that had its downside. I think you had to sublimate your own ego on the surface. Secretly you’re making your film, but at least on the surface you had to show that you’re being a company man. At least talk the talk. And it’s a lot of hard work. When I do a studio film I’m not slumming. I work just as hard on that to make it be as good as it possibly can and push everyone around me to work well.

3

In Paramount’s The School of Rock, for example, the slacker-rocker Dewey Finn embodies this curious paradox by exhorting his inhibited pupils to ‘Stick it to “The Man”!’ within a potential film franchise for a multimedia corporation. These crafted contradictions are even highlighted with some irony in Finn’s rallying cry to his class: ‘You gotta get mad at the man! And right now, I’m the man. That’s right, I’m the man, and who’s got the guts to tell me off? Huh? Who’s gonna tell me off?’ Nevertheless, although Jack Black’s performance of Finn imitating ‘The Man’ suggests a parodic impersonation of the major studio that funds the film/platform that he speaks from, Linklater subverts the whole project by constructing an audience-pleasing moral victory out of getting the pre-teen children of Republican parents to ditch their private elementary school studies and discover their truly creative vocations in rebelliousness and rock. Notwithstanding, Lesley Speed rightly defends the film against any accusation of complicity in the kind of anti-intellectualism that Jean-Pierre Geuens identified in the counter-cultural demand of the 1960s, namely that ‘art [should] be directly apprehended by the senses, without any training, any research, or any effort by the mind’ (Speed 2007: 100). Instead, she recognises an ‘inclusive scheme’ in the cinema of Linklater, ‘in which reflective and sensory experience coexist and complement one another’ (2007: 101). In other words, not only is it impossible to learn to plow by reading books, but rocking out and goofing off are vital to a fully-rounded education too.

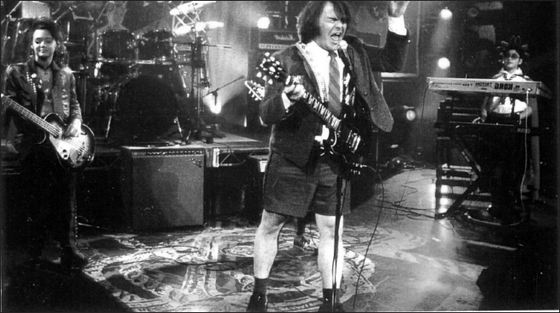

Clues to the subversive nature of this finely-tuned family film begin with the very first shot of the leather-jacketed back of a figure entering a club that is a direct homage to Kenneth Anger’s

Scorpio Rising (1964), an underground cult film about sado-masochistic, gay, neo-Nazi bikers. Finn will later curse the noxious effect of MTV on rock music and blame ‘The Man’ for its invention in gleeful defiance of the fact that MTV is owned by Paramount, which produced

The School of Rock. ‘We tapped into rebellion [and] were having our own fun. […] Even on the day [of filming that scene] we expected the phone to ring,’ admits Linklater on the region 2 DVD commentary. Many treated

The School of Rock as Linklater’s sell-out, but, as noted earlier, it is arguably the most subversive film to have come from a major American studio in recent years because it inspires kids to ditch their studies, disobey their Republican parents, band together and rock. As Linklater contends:

‘Sex Pistols never got an A!’ Dewey Finn (Jack Black) in The School of Rock

It was the first time I was ever cast as a director as I would cast an actor. And that was a very different script when I first got it. Very cheesy: they win the competition, donate the money to the school. We’d already got the commercial notes, the kids, etc., but now we thought, ‘Okay, let’s make it cool!’ And you could be really subversive!

Thus, any auteurist critique would define The School of Rock as Linklater’s most qualifying venture because his creative input corresponds to the myth of a filmmaker within the system being able to place his or her artistic signature on alien material. Linklater does make the film personally relevant to the extent that it corresponds to a subversive exposition of the slacker ethos within a feelgood family film by a major studio. Here again therefore, it may be argued, the influence of Luis Buñuel, whose films played at the Austin Film Society under the title The Subversive in the Studio is evoked, for The School of Rock might be best understood as a joyfully Buñuelian perversion of the ‘inspirational tutor’ genre typified by films such as Mr Holland’s Opus (Stephen Herek, 1995) and Music of the Heart (1999) directed by Wes Craven, a longer way from Texas than Linklater.

In addition, one of the main themes of

The School of Rock is creative control, which suggests something of the contradictory role of its director. Linklater came to the project at the urging of writer Mike White after Stephen Frears turned it down. Although always intended as a vehicle for Jack Black (who had inspired White to write it for him by running naked, music blaring, through the corridors of the apartment block they shared), Paramount’s removal of the script’s darker elements (including Finn having run over the teacher whose supply job he takes, references to the drug use of rock stars, and Freddy the pre-teen-post-punk drummer justifying his extant nickname ‘Spazzy’ with a case of Attention Deficit Disorder) was meant to turn

The School of Rock into a wholesome, family comedy. Under studio control but within his own working practice, however, Linklater still claimed a degree of autonomy for the creative process that is replicated in the way that the children are inspired to shape thesmelves into a rock band in montage sequences that Linklater claims on the DVD commentary are ‘great for representing collaborative efforts’. Finn is on a mission: ‘Dude, I service society by rocking, OK? I’m out there on the front lines liberating people with my music!’

The School of Rock is not really about ‘goofing off’ as one child says, but a viable alternative to systematised education that amounts to a pre-teen revolution in search of freedom, and as such it carries philosophical weight and a subversive charge.

The catalyst of music in The School of Rock as in Dazed and Confused ‘did what rock and roll was supposed to do – it unleashed a power and had a liberating and unifying effect,’ (Linklater 1993: 5). However, naiveté is ultimately avoided by having the kids premonitorily emulate the Bad News Bears of Michael Ritchie’s 1976 film (and Linklater’s subsequent remake) by losing the climactic Battle of the Bands. Moreover, they lose to a manufactured boy-band, which adds corrective realism to the fantasy of competing against a ‘Man-sized’ corporation. What The School of Rock provides is a metaphorical illustration of the collaborative work ethic that originates with Linklater’s experience of team sports: ‘I was always the team-sport kind of guy: baseball, football, basketball. I think because of the team efforts I had been involved in I realized that I like being a part of a team’ (in Smith G. 2006). This enthusiasm also corresponds to the political and social strategy represented in the production of most of his films including this, a studio project. In effect, although Linklater pragmatically assumed the responsibilities (no wastage, return a profit – check) and guise (apron, name-tag – cheque) of a director-for-hire, he still managed enough collaborative rebelliousness from Black, White and his child actors to twist the film into an assault upon the Republican values that govern institutions such as private elementary schools and major film studios. Far from a sell-out, The School of Rock is equal to the allegorical indictment of British public schooling and the class system that maintains it in Lindsay Anderson’s If… (1968), although it arms its pupils with musical instruments instead of machine guns. Thus The School of Rock demonstrates there is clearly much to be derived from the resources of a major studio like Paramount, not least the expansive budget for music rights that has long evaded Linklater, who got to compile a soundtrack for The School of Rock that harks back to the pre-punk and disco era of Dazed and Confused with The Clash, KISS, The Doors, AC/DC, The Who, The Ramones, Metallica, David Bowie, T-Rex and The Velvet Underground. Most importantly, Linklater was able to back up his request to Led Zeppelin to use their ‘Immigrant Song’ with a filmed plea by Jack Black in front of several hundred screaming fans and, of course, ready payment from Paramount several years after failing to get their song ‘Dazed and Confused’ from the album Led Zeppelin 1 (1969) for his film of the same name.

Dazed and Confused was one of several films that Linklater had been shaping since before

Slacker. His usual working practice involves these ‘superlong gestation periods’ (Anon. 1994) in which he makes and saves notes on cards: ‘I have a lot of movies I’m always doing this for: scenes, exact memories, ideas, and it slowly comes together in my mind’ (ibid.). His original idea for

Dazed and Confused was for all the action and characters on the last day of school in 1976 to be seen from inside a car (Spong 2006: 35). However, when critic Gary Arnold put in a good word with Jim Jacks, producer of

Raising Arizona (Ethan & Joel Coen, 1987), Linklater was invited to pitch the film to Universal. Asked to turn his awkward pitch into a script, Linklater structured his notes by adding a framework of songs from circa 1976 and then wrote the dialogue in a matter of days by using the music as an

aide memoire ‘to tap back into a period of my life I had long ago intentionally repressed [because] it was too painful’ (Linklater 1993: 5). He claims this script is his ‘most autobiographical moment to moment’ (Corn 1996), which suggests that Mitch is his alter ego by dint of age, although it was the part of Randall ‘Pink’ Floyd (Jason London) that he most often read opposite auditioning actors. Meanwhile, Jacks talked up the project’s similarities to

American Graffiti (George Lucas, 1973) to Universal chairman Tom Pollock, while ‘keep[ing] him away from

Slacker for as long as possible’ (Pierson 1996: 196). Thereafter, a decent budget (at least by

Slacker standards) enabled Linklater to create his collage of characters, events and sounds within the time-frame of eighteen hours from noon on the last day of school on 28 May 1976, which was recreated in Austin during the summer of 1992. He entrusted the casting to Don Philips, who had excelled at the same task on

Fast Times at Ridgemont High (Amy Heckerling, 1982), and selected his actors according to their correspondence with the available roles. Auditions yielded a roster of fresh talent, including Parker Posey, whose character of Tess Shelby in daytime soap

As The World Turns (1991–92) was conveniently in a coma, Cole Hauser, Ben Affleck, Rory Cochrane, Adam Goldberg, Marisa Ribisi, Michelle Burke, Joey Lauren Adams and Austinites Wiley Wiggins, Cristina Hinojosa and Matthew McConaughey, whose casting and enlargement of the role of Wooderson was particularly catalytic for the production.

4 Linklater made individualised mix-tapes of their characters’ kinds of albums for each actor and sent them all a ‘Dear Cast’ letter dated 16 June 1992 that promised: ‘If the final movie is 100 per cent word-for-word what’s in the script, it will be a massive underachievement’ (Linklater 2006a: 52). His aim of prompting the cast into living their roles led to them being billeted together in an Austin hotel, but the mix of East and West Coast actors produced a hormone-led, highly unruly commune. Nevertheless, Linklater was protective of his cast and put himself between them and the studio in order to protect rehearsals and rewrites that incorporated the creativity of his actors within a stifling schedule. The success of this process, he claims, pointing at the script, is that ‘all the best lines in

Dazed are in the margins’ (in Corn 2006). Indeed, great embellishment during rehearsal is evident in the workprint of the film, which features an extensive sub-plot about the pursuit of the KISS-ed bronze statues by the cops and several stand-alone scenes featuring aimless but entertaining banter amongst the actors.

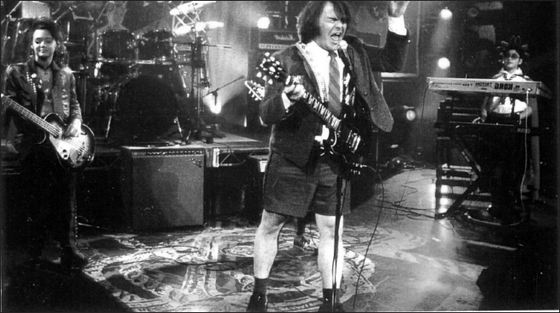

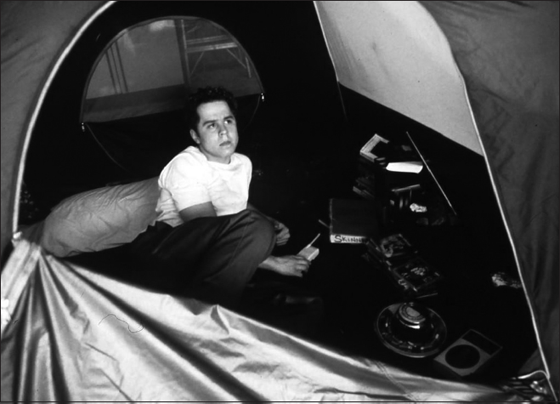

Slater (Rory Cochrane), Pink (Jason London) and Dawson (Sasha Jenson) in Dazed and Confused

Dazed and Confused firmly established Linklater’s favoured, cost-effective working practice of prolonged preparation for both writing and filming with rehearsals leading to rewrites but little actual improvisation during filming. The myth of favouring improvisation during filming that pursues Linklater is not just wrong but illogical because any filmmaker who has graduated from very low-budget filmmaking and, indeed, chooses to remain there, simply cannot afford to allow improvisation during a shoot because the inevitably ruined or inappropriate takes will use up the precious daylight, film, budget and patience of a low-to-no-salaried crew. Thus, on all films except The School of Rock, where the studio budget did allow Black to riff in search of comic rhythm with the child actors, Linklater aims to exhaust the scope for improvisation in rehearsal so that the actual filming is not wasteful:

I never have understood how people don’t rehearse much in movies. They come in, rehearse it, block it, shoot it. I insist on a lot of rehearsal. People say: “Three weeks of rehearsal! I’d rather be shooting!’ But no. Every day of rehearsal saves you a week of filming. You’re that much more prepared, that much more ready.

Linklater’s ambition to transfer the working ethos of Slacker to the studio production of Dazed and Confused was also signalled by his letter to the crew, which resembles extracts from Robert Bresson’s collection of working memos entitled Notes on the Cinematographer (1975). Bresson certainly influenced Linklater in the way he crafted spiritual themes by stripping back the aesthetics and the performances of his films in long takes that captured a delicate sense of time and expressed a potential for transfiguration. Bresson’s aim was a distinction between the cinema that he derided as filmed theatre and cinematography that entailed not reproduction but creation, wherein cinematography, which he believed had the special meaning of creative filmmaking, ‘thoroughly exploits the nature of film as such [and] should not be confused with the work of a cameraman’ (1997: 16). This, for example, is echoed by Linklater when he writes: ‘To avoid: the smell of the stage or theater. […] We are not recopying life – we are creating a new, cinematic life’ (2006b: 53). As would Linklater, Bresson aimed to ‘apply myself to insignificant (nonsignificant) images, [to] tie new relationships between persons and things which are, and as they are’ (1997: 19; emphasis in original) and to ‘catch instants. Spontaneity, freshness’ (1997: 34). In turn, Linklater writes:

Art is not in the mind but in the eye, the ear, the memory of the senses. […] Our images must exclude the idea of image. Not beautiful photography, not beautiful images, but necessary photography, necessary images. […] The real is not dramatic. Drama will be born after a combination of non-dramatic elements. (2006b: 53)

Such rhetoric also suggests Linklater’s desire to prove himself capable, authoritative and resistant to the studio’s expectations of a raucously sentimental teen movie. Although Dazed and Confused was a tightly controlled and slimly financed production by Universal, Linklater wrote that the mission of his cast and crew was: ‘Turning liabilities into assets: making (monetary) limitations our (creative) freedom’ (ibid.). He also snubbed the studio by prohibiting the use of fashionable Steadicam so that the film ‘looked seventies’ (ibid.) and clashed frequently with producer Jacks over scheduling, coverage and the amount of swearing allowed to actors such as Affleck, who tended towards a foul mouth when in full flow.

Linklater has said of Dazed and Confused that he ‘sold out from the very beginning [but] want[s] credit for suffering Universal’ (2006c). In pre-production he claims he ‘quickly had to learn to drop all references to [Luis Buñuel’s] Los Olvidados (The Forgotten Ones, aka. The Young and the Damned, 1950] and focus on the Animal House/American Graffiti/Fast Times at Ridgemont High holy trinity’ instead (Pierson 1996: 196). Yet, rather than trace the template of that triptych, Dazed and Confused maintains some fidelity to Buñuel’s nightmarish evocation of the slum-dwelling delinquents of Mexico City for it is a horror film about high school that takes nostalgia for its first victim. As regards the comparison with American Graffiti, which also takes place over one summer night (albeit in 1962), Dazed and Confused rejects what Robert Stam describes as that film’s ‘wistful sense of loss for what is imagined as a simpler and grander time’ (2000: 304) and instead subscribes to Coupland’s view that ‘we can no longer create the feeling of an era … of time being particular to one spot in time’ (2004: 75). Thus, says Linklater, Dazed and Confused sees high school as ‘a light prison sentence to be served. Once paroled you don’t look back’ (1993: 5). Instead of conjuring nostalgia, it presents the ‘shitty time’ (in Corn 2006) of high school with hazing rituals as horrific as the prom in Carrie (Brian De Palma, 1976), which was released the year Dazed and Confused was set. As with many of those in Slacker, the guise of being dazed and confused is one of self-protection for the film’s teenagers, whose recent past is alien (Vietnam, Watergate) and whose present is stagnating in the kind of fearful inertia voiced by Cynthia (Marisa Ribisi): ‘I’d like to quit thinking of the present, like right now, as some minor, insignificant preamble to something else.’

Ironically, Universal contradicted itself by planning for a marketing campaign based on nostalgia while declaring its intention to replace the original music with synergetic MTV-friendly cover versions by popular bands of 1993. In order to ensure the authenticity of the soundtrack, Linklater spent 15 per cent of the film’s entire budget on acquiring the rights to what he calls ‘the greatest hits of my freshman year’ (in Corn 2006) but was obliged to give up all his rights to royalties from the soundtrack album that would go double platinum in order to do so. This strategy included spending $100,000 on using Aerosmith’s ‘Sweet Emotion’ over the opening credits because Led Zeppelin had disallowed the use of their version of the song ‘Dazed and Confused’, which meant that

Dazed and Confused eclipsed the budget for

Slacker in its first three minutes. Says Linklater: ‘I got out alive with the film I wanted [and] the finished film was about 80 per cent of everything I needed’ (in Corn 2006). Marketing was hideous, however, with Universal so focused on the massive profit-to-budget return of $ 115 million USA gross on a $777,000 budget earned by

American Graffiti, with its nostalgia-trip to America before the assassination of JFK and Vietnam, that it ignored

Dazed and Confused’s contrary time and attitude to nostalgia. Because ‘Where were you in ‘62?’ was the tagline for

American Graffiti, it was decided that the poster for

Dazed and Confused would provide a crass, intertextual riff on that sentiment: ‘It was the last day of school in 1976, a time they’d never forget … if only they could remember.’

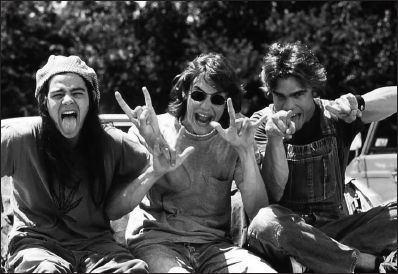

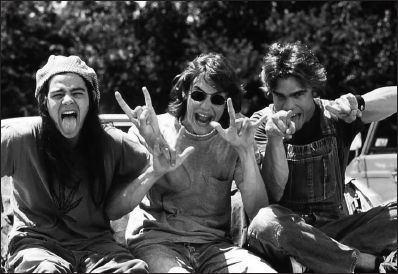

Wooderson (Matthew McConaughey), Slater (Rory Cochrane), Shavonne (Deena Martin) and Simone (Joey Lauren Adams) in Dazed and Confused

Dazed and Confused actually gets its title from being set just one year after the fall of Saigon (dazed) and during America’s Bicentennial celebrations (confused) and is therefore resentful of the propaganda that underscores nostalgia. ‘It’s impossible to have much nostalgia for that time period,’ insists Linklater (1993: 5). None of the teenagers in

Dazed and Confused relish the time they are living in. Instead they adhere to Cynthia’s complaint that ‘the seventies obviously suck’ and collude with Pink’s summation: ‘All I’m saying is that if I ever start referring to these as the best years of my life, remind me to kill myself.’ As Linklater claims, the film explores ‘the plight of the teenager: trapped and oppressed, but with the budding consciousness of being trapped and oppressed, but still trapped and oppressed nonetheless’ (1993: 5). Where the film might have connected with the youth demographic on its release in 1993 was in its illustration of unease at the extent of policing in the year that saw the FBI raid the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas and the beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles police. Resonance may be detected in the bullying team coach and his imposition of an anti-drugs pledge that is one of the film’s few concessions to narrative, but

Dazed and Confused ultimately illustrates this unease as a political divide that suggests an emerging social schism. On the one hand there is the hyper-aggressive selfishness of older males like sadistic bully Bannion (Affleck) and on the other there is the liberal teacher Ginny Stroud (Kim Krizan, co-writer of

Before Sunrise), who warns her pupils that ‘with all this American bicentennial Fourth of July brouhaha, don’t forget what you’re celebrating, and that’s the fact that a bunch of slave-owning, aristocratic, white males didn’t want to pay their taxes’. In between is the impulsive but harmless hedonism of those stranded in the 1970s between the hippie culture of the 1960s and the slacker culture of the 1980s. Only the kind of self-awareness expressed by Mike (Adam Goldberg), Cynthia and Pink recognises that even the most minor tactic of self-determination can become a viable crusade. Thus, Pink refuses to sign the pledge, Cynthia escapes her own bookish stereotype by hooking up with Wooderson and Mike answers the question of what he is going to do with his life if he does not go to law school with the line: ‘I wanna dance!’ Like Mike, perhaps, Linklater considers it ‘part of the healing process to turn attention away from the society that has let everyone down and to focus on where the party is’ (1993: 6). Unfortunately, after botching its marketing, Universal delegated the film’s distribution to a short-lived company called Gramercy Pictures that was formed as a joint venture with PolyGram and fumbled a ‘half-assed release’ (Pierson 1996: 196).

Dazed and Confused thus became what Linklater calls ‘the worst of both worlds: a studio production with independent release’ (in Corn 2006). Nevertheless, a cult was born on enthusiastic reviews from Roger Ebert, who called it ‘art crossed with anthropology’ (1993), Peter Travers of

Rolling Stone, who also wrote of Linklater’s ‘anthropologist’s eye’ and described the film as ‘a shit-faced

American Graffiti … loud, crude, socially irresponsible and totally irresistible’ (2000), and Owen Gleiberman in

Entertainment Weekly, who argued astutely that Linklater was no mere pop anthropologist but the creator of an ‘Altmanesque’ film that represented ‘the first era in which teenagers communicated by wearing their media-addled brains on the outside’ (1994).

As Linklater was himself one of these teenagers it is tempting to draw parallels between his own graduation from the innocence of

Slacker to the experience of

Dazed and Confused and the hazing rituals inflicted on Mitch Kramer in the latter. Wooderson delivers the slacker philosophy late in

Dazed and Confused but this only vaguely prefigures the spirit of the Austin that features in

Slacker: ‘The older you get, the more rules they are going to try and get you to follow. You just gotta keep on livin’, man. L-I-V-I-N.’ The moral certainly resonates with Linklater’s dropping out of university to study literature and film on his own terms and his subsequent reluctance to deal with major studios on a scale that removes too much autonomy from his own productions. However, this determination to maintain his independence has also been contradicted by his never again writing an original script after

Dazed and Confused without credited collaborators and, moreover, mostly thereafter seeking to adapt pre-existing material. Besides

Before Sunrise, which originated with Linklater meeting a woman in a Philadelphia toy shop and spending the night walking and talking, no other film of his besides

Boyhood foregrounds any autobiographical element. Instead, Linklater’s relative autonomy has mostly obscured or operated as a shield for the collaborators who have vitalised and supported his own filmmaking ambitions. Thus, only

Slacker and

Dazed and Confused are self-penned originals and the interrelated

Before Sunrise and

Before Sunset were the only two jointly-authored original scripts prior to

Bernie (2011), which was co-written with Skip Hollandsworth. Otherwise, there is but one self-penned adaptation of a novel (

A Scanner Darkly) and two adaptations of works of non-fiction in collaboration with their authors: Claude Stanush’s

The Newton Boys and Eric Schlosser’s

Fast Food Nation. The first of these involved Linklater and Stanush embarking upon a substantial research project; the second saw Linklater and Schlosser writing independently and together over a period of several years (Feinstein 2006).

More than writing, Linklater has indulged his enthusiasm for actors and acting by filming two adaptations of plays by their authors (Eric Bogosian’s SubUrbia and Stephen Belber’s Tape [1999]), as well as one adaptation of a novel with a theatrical background (Robert Kaplow’s Me and Orson Welles [2008]) from a screenplay by Holly Gent Palmo, a former production coordinator on Dazed and Confused, whose first writing credit this was. Bad News Bears was based on a script by John Requa and Glen Ficarra that hewed so closely to Michael Ritchie’s 1976 film of the same name that its writer Bill Lancaster, who also wrote its two sequels and died in 1997, received a posthumous credit on the rather redundant remake. And, finally, it might be noted that in Linklater’s present filmography there are several sequels to films that Linklater has himself directed. Perhaps, for a filmmaker who takes time as his most enduring theme, whether it be depicted in time-frames, alternate realities or parallel lives, a sequel offers a particularly apt and significant vehicle for its exploration. Thus, there is Before Sunset, Before Midnight (and its possible sequel), the postponed ‘spiritual sequel’ to Dazed and Confused and The School of Rock 2: America Rocks written by Mike White. Another is Last Flag Flying, a sequel to The Last Detail (Hal Ashby, 1973), which further underlines Linklater’s empathy with the generation of American filmmakers sometimes referred to as the ‘Hollywood Renaissance’ that included both Ashby and Ritchie alongside Altman.

Although debate may continue as to whether Linklater is a filmmaker dependent upon adaptable texts and rehearsal or one favouring originality and improvisation, there is no doubt about the importance to his cinema of collaborators.

Slacker was a wholly collective effort on which Linklater found himself ‘suddenly the head coach’ (in Lowenstein 2009: 23). He even recalls ‘at the end of the day, when the film came out, some were a bit surprised. Oh, so it’s

your film?’ (in Lowenstein 2009: 26; emphasis in original). However, it would not be long before Linklater was invited to pose for a

Vanity Fair article on new filmmakers illustrated by Annie Leibowitz’s portraits of Robert Rodríguez, Alexander Rockwell, Allison Anders, Rob Weiss, Gregg Araki, Stacy Cochran, Todd Haynes and Carl Franklin that coincided with the release of

Dazed and Confused. But such premature consecration apart, as for

Slacker and every film of Linklater’s thereafter, the script of

Dazed and Confused remained unconditionally malleable throughout rehearsals. On

Waking Life Linklater even estimates that only about one third of the finished material was scripted and another third was developed by the cast, while the final third was the product of ad-libs made possible by filming inexpensively on video. The original credit for the screenplay was to Linklater ‘with additional dialogue by numerous cast members’ but The Writer’s Guild disallowed this. Yet, despite the Writers’ Guild’s failure to celebrate collaboration, Linklater clearly favours working closely with the writers and co-writers of stories, scripts and screenplays as well as with the cast. McConaughey’s Wooderson in

Dazed and Confused is a prime example of this, for his drawl and demeanour make an endearing icon out of what, as written, could so easily have resulted in a much sleazier hanger-on.

Some American actors like McConaughey, Affleck and Posey thrive on this freedom to embellish; others like Michelle Forbes, who gave a vibrant audition as Jodi, shrink away or become mannered during filming.

5 Nevertheless, Linklater deploys a similar methodology on all his films including

Tape, for which he claims to have ‘rehearsed the hell out of it before though. It was an old idea of mine to have something so well planned, then to shoot it very spontaneously’ (in Anon. 2009d). As he says on the DVD commentary of

The School of Rock, ‘the ultimate compliment’ an audience can make of a film is that it appears to have been improvised, even when the appearance of spontaneity comes from a confidence created in rehearsal and the natural fluidity of long takes that,

Dazed and Confused apart, are often filmed with understated Steadicam. It also comes from casting actors who perform well in his more Altmanesque, multi-character films, while Jack Black in

The School of Rock and Billy Bob Thornton in

Bad News Bears provided not just an anchor but a spur for the performances of the child actors, although in

Bad News Bears they barely transcend stereotyping, perhaps because they all have to share a baseball bat instead of exploring and expressing their identities on different instruments. In sum, it is Linklater’s stated opinion that ‘90 per cent of filmmaking is casting your collaborators’ (ibid.).

Most notably, this enthusiasm for collaboration often seeks correctives to Linklater’s own weaknesses. Following what he describes on the Criterion Collection DVD commentary as the ‘fairly Charlie-Brownish’ script of Dazed and Confused in which grown-ups hardly appear and only Parker Posey and Marisa Ribisi transcend the stereotype of pliant femininity as the gleefully sadistic Darla and the warmly intellectual Cynthia, Linklater employed Kim Krizan to provide an authentic, adult voice for Céline in the writing of Before Sunrise. Krizan had played Questions Happiness in Slacker and the high school teacher in Dazed and Confused and would expound upon the theories of Ferdinand de Saussure in Waking Life, and was ideal for Céline, says Linklater, because he ‘loved the way her mind worked – a constant stream of confident and intelligent ideas’ (1995: 5). Before Sunrise was ‘conceived to take place in San Antonio’ (Pierson 1996: 197), just 60 miles south-west of Austin and, like Dazed and Confused, was a project that Linklater had been developing for several years; but it was only by working with Krizan that the basis for the film’s dialogue was established in the working process. Krizan recalls: ‘We’d pieced together a plot (or non-plot as some would have it, but I’d call it “internal drama”) and then we’d duel with words via turns at the computer’ (1995: 6). After many discussions ‘the conversations that make up the movie’ (Linklater 1995: 5) were written down and followed by a meeting with Hawke and Delpy in Austin that Krizan describes as an ‘intimacy boot-camp’ (1995: 6) that marked the beginning of a rehearsal process that ‘didn’t end until we shot the last scene in the movie’ (Linklater 1995: 5). This working process made the production of Before Sunrise, ‘an exploration analogous to the relationship in the movie’ (ibid.) in which the writing and rehearsal merged naturally into the film’s actual production, where Hawke and Delpy continued fleshing out their characters in Vienna.

One of the longest gestation periods in Linklater’s career was reserved for

Before Sunset, which in 2004 added nine actual years to the five or so that had preceded the prequel. Returning to characters that they had briefly revisited for a scene that had been rotoscoped for

Waking Life, Hawke, Delpy and Linklater started writing the script together in 2002 and re-ignited the project properly over five months in 2003–4. In this collaboration that mirrored the fiction they were creating, their writing, rehearsal and re-writing produced 75 pages of dialogue that they would subsequently film in long, unbroken takes on a fortnight’s shoot on the streets of Paris. Delpy claims the success of this collaborative process was self-evident: ‘I wrote most of my dialogue, some of Ethan’s dialogue, and Rick wrote some of my and Ethan’s dialogue – and vice versa. We wrote the structure and story together. We came up with the concept together’ (ibid.). Linklater also promoted Delpy’s identification with the role by basing his contributions to Céline’s dialogue on excerpts from a ‘thirty-page essay that [Delpy] wrote after George Bush got elected, afraid that he’s all about war’ (Peary 2004). By the time of filming, as is typical of Linklater’s budget-savvy avoidance of costly improvisation, the actors did not improvise much at all because everything was written, mapped out and rehearsed.

The myth of on-set improvisation that is erroneously attached to Linklater comes from his cast hewing so closely to their characters in rehearsals that the need for embellishment is exhausted with the result that their acting becomes seemingly more behavioural. In addition, the complementarily loose, naturalistic tone of his films comes from the long takes, fluid camerawork and evocative rhythms of the dialogue. The myth of spontaneity is the director’s typically contrary objective, however, for it results from his dedication to prolonged writing and rehearsal and experimentation with filming methods. In sum, it takes a lot of time, practice and effort to look this casual, which is not to say that Linklater limits his eventual filming to single takes, but that the nuances of crafted dialogue come from an exploration of the words rather than from their dismissal. The centrifugal force of improvisation, which is based upon actors moving away from the core dialogue or direction, is avoided. Instead it is replaced by the centripetal emphasis on exploring the dialogue as written according to intimate direction until its delivery is wholly appropriate to the overall vision and in character. Linklater thus contradicts assumptions of his cinéma vérité style of filmmaking (which includes consideration of what lies beneath the animation of Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly) by being actor-centred and theatrically influenced in the manner that he challenges and dissects but ultimately wholly respects the text. And, therefore, at least one apparent contradiction that can be dismissed is the fact that he has directed faithful film adaptations of two plays for which he left the major task of their adaptation to the original playwrights.

Linklater’s adaptation of Bogosian’s play

SubUrbia emphasises the darkness and potential for depression beneath the surface of several of his films while at the same time suggesting that Linklater may be unable or unwilling to reach those depths in his own writing. Nevertheless, an attempt to map a chronology of his cinema based on the evolution and ageing of the protagonists would begin with the initiation into adolescence of Wiley Wiggins in

Dazed and Confused and move onto his metaphysical entry into adulthood with

Waking Life, which ends with him drifting away and therefore becoming, perhaps, the ‘drifter’ of

It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books, who returns to Austin in the first scene of

Slacker. There is the brief escape of

Before Sunrise, which sees this American slacker connect with his European ancestry, heritage and soulmate, while the twenty-something slackers who hang out on the smalltown street corner in

SubUrbia disprove the hope expressed by Cynthia in

Dazed and Confused that ‘maybe the 1980s will be like radical or something. I figure we’ll be in our twenties and it can’t get worse.’ As stated, Linklater’s universe is not very big, although at this point in the constructed chronology it does point to the buffoonish disciple of slacking that is Dewey Finn in

The School of Rock and his possible destiny as the washed-up Morris Buttermaker in

Bad News Bears. The fluke reunion of

Before Sunset is a blissful option that is as yet undreamt of by the characters in

Waking Life and an impossible ambition for those in Bogosian’s play

SubUrbia, which had its debut in the Lincoln Center Theater’s 1994 Festival of New American Plays in New York and was described in

The New York Times as ‘Chekhov high on speed and twinkies’ (Richards 1994).

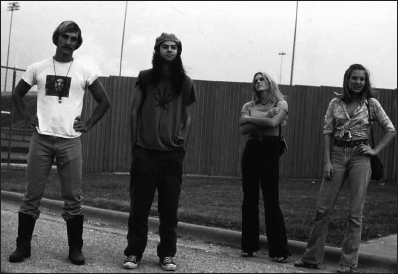

Richard Linklater (right) and Lee Daniel filming SubUrbia

Bogosian is an amalgam of playwright, actor, novelist and monologist, who developed

SubUrbia as a character-based workshop with student actors and set it in the fictional town of Burnfield, which represents his home-town of Woburn, Massachussets. Linklater recognised Burnfield as a metaphor for Austin too and its characters as the subjects of a post-mortem of the city’s slacker culture. Hanging out all night like slacker vampires, they throw their beer cans, cigarette butts and pizza boxes on the ground in front of the convenience store and themselves into or against the dumpster beside it. An attempted suicide, a suggested rape, and murder are just some of the night’s events. Mostly listless and lacking focus, each of these characters will explode with anger over trivial matters, while the American dream is chased regardless by the Choudhurys, the immigrant Pakistani couple that runs the store. Links to the original play include Steve Zahn and Samia Shoaib repeating their roles as Buff and Pakeesa Choudhury, while Linklater hewed closely to the text and filmed with an emphasis on two-shots that best served the speed of Bogosian’s dialogue.

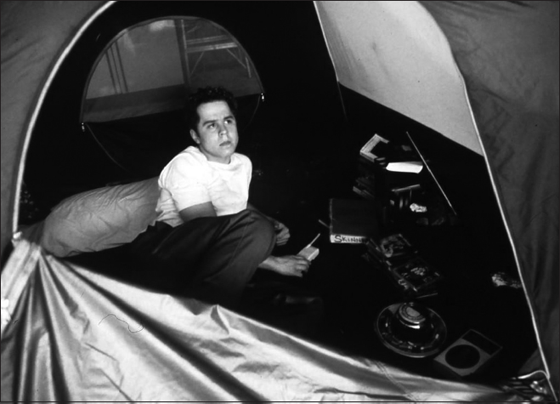

Jeff (Giovanni Ribisi) lives in a tent in his parents’ garage in SubUrbia

The experience was similar for Stephen Belber when adapting Tape, which he wrote in 1999 as a vehicle for actor friends. Tape is a one act play/film depicting the abrasive, vengeful reunion of three people who have their distant high school friendship in common but also conflicting memories of a possible date rape inflicted by Jon (Robert Sean Leonard) on Amy (Uma Thurman), the ex-girlfriend of Vince (Ethan Hawke, Thurman’s spouse at the time). Hawke sent Linklater the text of Tape after reading it at an acting workshop and it fitted the director’s remit of a small-scale, inexpensive feature shot on digital video in one week for the InDigEnt collective of which Linklater and Hawke were part. After extensive rehearsal, Tape was shot very quickly on hand-held cameras by Linklater and Maryse Alberti on the single, cost-effective soundstage set of a motel room. Belber meanwhile found adaptation a natural progression from the play that he subsequently rewrote after finishing the screenplay and he has since collaborated with Linklater and Hawke on developing a screenplay for a biopic of Chet Baker (Smith G. 2006). He recalls the production of Tape as precise and faithful to the dialogue with improvisation limited to Hawke’s ‘P for Party’ routine: ‘Otherwise it was pretty word-for-word, and when there was a change, it was discussed by the group’ (ibid.).

This privilege afforded fellow Austinite Ethan Hawke prompts recognition of the actor as the most visible of all recurring collaborators in the cinema of Linklater. Hawke has acted in

Before Sunrise, The Newton Boys, Tape, Waking Life, Before Sunset, Fast Food Nation and the ongoing project known as

Boyhood. Consequently, he might get fitted for the role of Linklater’s alter-ego in an auteurist approach to his cinema if it were not contradictory to seek an onscreen alter ego for a filmmaker who is so intensely collaborative. Only overriding directorial control can fashion a

doppelgänger, otherwise the nature of true collaboration prevents it. Hawke’s four incarnations of Jesse in

Before Sunrise, Waking Life, Before Sunset, and

Before Midnight, his charming drunk Jess in

The Newton Boys, his wolfish Vince in

Tape and his radical Uncle Pete in

Fast Food Nation have little in common besides Hawke. There is therefore no recurring representation of Linklater in his cinema and little chance of a reading that might, following Barthes, be ‘tyrannically centred on the author, his person, his life, his tastes, his passions’ (1982: 143). The explicit emphasis on collaboration in form and content, the plethora of adaptations and the generic basis to much of Linklater’s work means that there is simply no ‘more or less transparent allegory of the fiction, the voice of a single person, the

author “confiding” in us’ (ibid.). Nevertheless, the grouping of disparate films around the figure of their director does allow for analysis of how a particular filmmaker influences the way films come to be funded, produced, distributed and received. Barthes contends that ‘to give a text an Author is to impose a limit on that text, to furnish it with a final signified, to close the writing’ (1982: 147); but the critical strategy of centring analysis on an individual whose role in the creative process is essentially collaborative in its ethos as well as in its practice does demarcate a field of study for discovering how that figure functions within specific contexts such as independent American filmmaking, Hollywood and contemporary art-house cinema. In addition to directing, Linklater is a writer, adapter and sometime cinematographer with special concern for actors and an interest in unusual technologies such as rotoscoping. To group together his films and the contradictions therein is not to ‘find’ or ‘explain’ the author but rather to enter into ‘a multidimensional space […] drawn from the innumerable centres of culture’ (Barthes 1982: 146). The only myth to overthrow with Linklater is the one of ‘independent’ filmmaker and he characteristically collaborates on this with his audience by demolishing it himself. Pronounced and enduring collaborations, a reliance on the adaptation of other sources for the subject of his films, a career-long negotiation of production and distribution deals, occasional commissions for major studios, the comparative lack of a performative persona in the manner of, say, Quentin Tarantino, Kevin Smith or Spike Lee, his objective criticisms of slacking and his refusal to be the spokesperson or mascot of that ‘movement’ all add up to the dissolution of the qualities necessary to authorise the award of auteur to his work as a no less dedicated filmmaker.

Beyond reverential references to films such as Vincente Minnelli’s

The Clock in

Before Sunrise, Hitchcock’s

Rope (1948) in

Tape, and

Detour (Edgar G. Ulmer, 1945) in the naming of his production company, Linklater’s cinema is most similar in form, content, aesthetic and meaning to those American filmmakers whose European influences are evident in the practice and theory of their cinema. Cassavetes and Sayles are obvious touchstones for any filmmaker with aspirations to independence because of their individualistic response to major studios and distribution, but it is also their naturalism, collaborative working practice, dedication to the craft of acting and frequent emphasis on time rather than narrative as the structural determinant of their films that influences Linklater. Between Cassavetes, Sayles and Linklater, moreover, is Jim Jarmusch, whose sad and beautiful cinema turned a sense of pessimistic urban dislocation into optimistic nomadism. Anchorage in Jarmusch’s cinema is provided not by family or tradition but by a universal pop culture sensibility that has proven contagious to much of the American ‘indie’ sector. Similarities with the cinema of Linklater are also revealing of a curiously philosophical approach to the way that Americana affects and informs human connections.

Permanent Vacation (Jim Jarmusch, 1980) is a study of estranged youth with marked similarities to Linklater’s

It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books, while

Stranger than Paradise (Jim Jarmusch, 1984) evokes the terse approach to personal growth that is incorrectly interpreted as time-wasting in

Slacker. Following this, Jarmusch’s

Mystery Train (1989) evokes the same waylaid romanticism of people passing through a city as

Before Sunrise, while his

Night on Earth (1991) is very much like

Waking Life in the way that it evokes an ultimately unresolved search for a philosophical meaning to parallel lives and realities within a strict time-frame. Jarmusch’s attempt at a western with

Dead Man (1995) may have been far grimmer than Linklater’s

The Newton Boys but his

Coffee and Cigarettes (2003) was a film in which successive, solipsistic scenes of dialogue between hangers-out in a bar referenced both Godard and Altman and brought to mind Linklater in its Cubist approximation of looking through a prism at a specific time and place. Jarmusch’s low-budget intimacy is a clear influence on Linklater, as is the wayward pacing within a delineated time-frame of several of his films, the use of parallel, simultaneous storylines and an occasional dreamlike quality that are all in the service of films that seem meaningfully at odds with their contemporary American surroundings.

Jarmusch did not follow his contemporary filmmakers into working for the majors, although ‘many of his films after

Stranger than Paradise are increasingly responsive to commercial and genre filmmaking’ (Suárez 2007: 47). The same is mostly true of Linklater, whose independence has not precluded his collaborations with the major studios nor his ‘film attempts’ at genres. Despite his reputation as a purveyor of structural, aesthetic and philosophical elements, as previously stated Linklater is remarkably adept with genres. To date he has directed a road movie, a western, a high school comedy, a romantic comedy and its sequels, a black comedy, a television situation comedy, a couple of claustrophobic dramas, a sports comedy, a sort-of musical family film, a science fiction film and animation combined, as well as two documentaries and the recently fashionable kind of multi-narrative, multi-character social drama that is

Fast Food Nation; but none of these exercises in genre are particularly escapist. The road movies go nowhere, the western ends not in a shoot-out but on a chat show, the high school comedy finds nothing to laugh about in being a pupil, the first romantic comedy ends with separation and the second fades out before the kiss, the team in the sports comedy loses as does the rock band in the musical, the situation comedy finds little to laugh about in its particularly grim situation, the animated science fiction explains itself as madness and the social drama is ultimately about apathy more than activism. Adeptness notwithstanding, therefore, the appearance of genre filmmaking sits uneasily with Linklater because his films’ idiosyncrasies undermine generic conventions, and whether this justifies an auteurist-by-default approach to his cinema is an argument plagued by unending contradictions.

After Jarmusch, the emerging American filmmaker with whom Linklater briefly had most in common in the early 1990s is Whit Stillman, whose Metropolitan (1990) utilised character-driven dialogue and camerawork that shifted between the individuals and alliances of a group of Manhattan debutantes to observe America from the other end of the social spectrum from Slacker. Stillman has directed only three films since (and an episode of Homicide: Life on the Streets for television) but he belongs with Todd Haynes, Hal Hartley and Linklater, who has stated:

I think there are two kinds of filmmakers. Ones that had their little 8mm cameras and their trains and were setting fires and blowing them up and crashing them into each other, and then there were the ones who read a lot and were going to the theater and maybe reading philosophy. (In Price 2003)

Although Linklater belongs in the second group, like Pink in Dazed and Confused he has an ability to move between cliques that perhaps explains his comparative productivity and longevity. Theatre and philosophy apart, Linklater is also part of the home video generation that swiped cinephilia from the film school generation of Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese and Paul Schrader and used offbeat (if not always original) dialogue and characters to compensate for rudimentary production values (if not technique). Tarantino’s performance of auteurism may be understood in terms of Timothy Corrigan’s view of how the auteur operates at the level of post-production ‘as a commercial strategy for organizing audience reception, as a critical concept bound to distribution and marketing aims that identify and address the potential cult status of an auteur’ (1991: 103). However, that of Linklater operates more at the pre-production end of the process, as a name whose wavering bankability can sometimes attract investors and actors for low-budget, collaborative projects. In contrast, Tarantino exemplifies the manner in which ‘today’s auteurs are agents who, whether they wish it or not, are always on the verge of being consumed by their status as stars’ (Corrigan 1991: 106). Whereas Tarantino is a star, Linklater is a character actor. Stars open pictures and get them green lit, whereas Linklater’s recent films have either struggled at the box office (Fast Food Nation), failed to attract adequate distribution (Me and Orson Welles), not survived the endless negotiations of pre-production (That’s What I’m Talking About) or fallen victim to economic crisis (Liars (A-E)), which was a casualty of the downsizing of Miramax in 2010). Thus, perhaps, the ultimate contradiction presents itself: might the popular and critical sense of Linklater’s auteurism be based on exactly this kind of relative failure? As soon as he has success with The School of Rock, for example, his fan base with its auteurist dogma and reservist celebration of independence accuses him of selling out. On the other hand, Linklater blames the commercial failure of Dazed and Confused, A Scanner Darkly and The Newton Boys on their mis-marketing:

They ran from the period elements. I offered to make my own posters.

The Newton Boys was a homage to the old cinema and they portrayed it as a shoot ’em up. They put it in a genre in which it couldn’t compete. These guys weren’t psychopaths, they didn’t want to kill people, so it fails on that level.

However, following Corrigan, it is at least arguable how much of his own contradictory auteurist status is at fault. Does his fan base avoid these films because the marketing convinces them they are generic films for a general audience, or does the general audience avoid them because the marketing fails to convince them that, despite appearances to the contrary, they are probably introspective art-films with long pauses where the action should be?

This contradiction might at least suggest how audiences for both independent and mainstream cinema subscribe to an extant and media-inflated notion of auteurism. Nevertheless, in order to make sense of the cinema of Linklater as a unifying, structural concept it is useful to associate it more with aspects of filmmaking in Europe than with those of several of his American peers. The working practice that affected, informed and defined the most significant filmmakers from the UK, Italy, Germany and France in the 1950s and 1960s was developed in a post-war industrial vacuum that resulted from widespread destruction, not only of property but of confidence in the arts. It was the availability of lightweight cameras, portable sound equipment and faster film stock that enabled those filmmakers whose work would come to be classified as Italian Neo-realism, New Spanish Cinema, British Social Realism, New German Cinema and the French New Wave. However, although the post-war regrouping of battered nationalisms indicated by these labels reflects the particular origins and contexts of each group, it also limits appreciation of how they relate to each other. Post-war European cinema was often a transnational movement in mood at least in which the angry young men of British social realism had their counterparts in the German loners, resentful Spaniards, French rebels and Italian chancers (and, subsequently, Linklater’s slackers). Their films illustrated in content, form and practice the necessary new freedoms afforded filmmakers. This was not even limited to Europe, for the same opportunity was grasped by Cassavetes, whose small-time gangsters and night owls suit the same social grouping so well. What key films by Fassbinder and Wenders, Godard and François Truffaut, Vittorio De Sica, Roberto Rossellini, Carlos Saura, Cassavetes and Jarmusch had in common was the guerrilla-style production that complemented the pursuit of meaning. Rough-edged and rebellious, the films and their protagonists were merged in street level tussles with the kind of obstacles that previously only documentary-makers had encountered. These in turn inspired experimentation and, arguably, an ingrained methodology and mythology of film production that became an inextricable knot of aesthetic and philosophical clichés. As Richard Brody writes of Godard:

The simplified technique of

Masculine Feminine offered a method – one that specifically befit the director’s independent film about young people, the modern cinematic Bildungsroman. It became a method that was used for more or less every first-person classic of beginning filmmakers, from

Clerks and

Slacker to

Go Fish and

Judy Berlin. (2008: 268)

Nevertheless, Brody is rather ungenerous in limiting the technique to films about youth, for it has also distinguished films that deal with adults, as well as pop culture. In recent years the ambit of American ‘independent’ cinema has been dominated by low-budget films that utilise the technique to support their marketing in search of breakout or crossover success. The glut of films that match naturalism to self-conscious quirkiness as evidence of an ‘indie’ sensibility (e.g. Napoleon Dynamite [Jared Hess, 2004], Little Miss Sunshine [Jonathan Dayton & Valerie Faris, 2006], Juno [Jason Reitman, 2007], The Wackness [Jonathan Levine, 2008], and so on) has overtaken the kind of ‘indies’ for adults made by Cassavetes and Sayles. What Linklater, Stillman, Lee, Smith, Hal Hartley, Rose Troche, Todd Haynes and Darren Aronofsky share is the same penchant for seeing the world through widescreen spectacles that afflicts the most movie-minded filmmakers such as Steven Spielberg, Scorsese and Tarantino. Yet, at least when starting out, in reflecting the media-saturated environment of their generation these exemplaries commented to varying degress upon that situation and condition rather than merely exacerbating it. Like Slacker, films such as Metropolitan, She’s Gotta Have It (Spike Lee, 1986), Trust (Hal Hartley, 1990), Poison (Todd Haynes, 1991), Clerks (Kevin Smith, 1994), Go Fish (Rose Troche, 1994) and Pi (Darren Aronofsky, 1998) do not merely imitate but innovate. They make the techniques associated with the French New Wave and Godard in particular resonant and relevant to contemporary sectors or communities of American society. Arguing for the kind of political and philosophical depth that might close the space between Godard and Linklater may seem pretentious, but as Céline says in Before Sunrise, ‘the answer must be in the attempt’.

Linklater’s offices for Detour Filmproduction in Austin Film Studios are festooned with original Polish, French and American film posters and many of the largest advertise the films directed by Godard, whose influence on the cinema of Linklater is more than just working practice. Godard sought a form and style that would enhance meaning, and the rebellious youths he made the subject of his films were just as media-addled as Linklater’s; but for them the only media was film. Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo) in

À bout de souffle (

Breathless, 1960) may be a sociopathic thief hunted by the police but, spontaneous murder apart, he is also a slacker whose pursuit of leisure, Patricia (Jean Seberg) and the elusive cool of Bogart is an impulsive response to the fatalism that infects his left-ish view of burgeoning consumerism in post-war France: ‘Shall we steal a Cadillac?’ The techniques that Godard utilises to express the impulsiveness of this content in the film’s form include hand-held camerawork, jump cuts, direct address (or at least sly asides) and a general disdain for such conventions as the 180 degree rule, which communicates the logic of action by the positioning of the camera but is here abandoned like the dog-end of a Gauloise. Here is life liberated from the limitations of filmmaking and, at the same time, teasing those same limitations of the frame, time, place, narrative and audience. Godard’s decisive neglect of narrative conventions and continuity means that

À bout de souffle combines Neo-realism with so many dislocating techniques that the effect is borderline Surrealism. Yet this does not preclude Godard’s love of generic signifiers in the example of Michel’s embrace of the tough-guy persona, which remains an ironic but affectionate pose right up until his death, when he accepts that his French imitation cannot but fail to embody the American myth precisely because the myth is a fallacy: ‘C’est vraiment degueulasse’ (‘It is very disgusting’). Nevertheless, in Michel’s imitation of Bogart that complements Godard’s dedicating the film to Monogram Pictures, which made low-budget films between 1931 and 1953, there is an admission of addiction. As Michel says, ‘informers inform, burglars burgle, murderers murder, lovers love’, which explains the troubled relationship between the French New Wave and the hegemony of Hollywood, its resentment of Hollywood’s control of distribution and the colonising iconography of its fictions, while, at the same time, acknowledging its surrender to the seductive beauty of Hollywood product. Although increasingly political in his film form and content, Godard does not pursue specificity but explores instead the complexity of any matter. A parallel with some ‘independent’ American filmmakers of the 1980s and 1990s thereby occurs, whereby the purposeful disdain for the specificity of conventional narrative in

Slacker, for example, represents a refusal to conform to a single narrative or shape a quest for resolution that is rebellious in its form, style and content. Here, the long takes, fluid camerawork and resistance to remaining with any one of a hundred possible narratives is the form/style that expresses the content of these same slackers, following their intuition and refusing to conform to any conventional careers or lifestyles. It also embodies a rejection of Hollywood that is expressed not by the pretence of force but by one of ironised nonchalance. Like Jeff in

SubUrbia, who protests about the ‘mosh-pit of consumerism’ that is a fast food joint but cannot afford to eat anywhere else, Michel in

À bout de souffle rejects Hollywood while feeding his ego with its product.

Furthermore, what Godard has in common with several of his American contemporaries and followers is a concern with the causes and effects of the war in Vietnam. The French perspective on the conflict, with all its post-colonial baggage, is far more ambiguous than that of the superpowered USA’s failed fight against Communism. When distance from defeat and its domestic shockwaves allowed, American cinema finally responded by imposing linear narratives onto a war that was as inconceivable and inexpressible within conventional arts as Godard and Deleuze claimed of the Holocaust. Instead, generic linear narratives such as

Platoon (Oliver Stone, 1986) offered a

Bildungsroman that allowed America to put the war down to experience. In contrast, Godard tackled the conflict in 1965 with

Pierrot le Fou, which explores the collusion of film in the subject’s complexity in its inclusion of a nonsensical playlet for American tourists put on by Ferdinand (Jean-Paul Belmondo) and Marianne (Anna Karina) in which the absurd stereotypes of her Vietnamese peasant woman and his Yankee sailor unite by scrawling ‘Vive Mao!’ (‘Long live Mao!’) in chalk. However, for Godard, politics was not so much present in rhetoric as in the Marxist underpinning of film form itself: in the allusions, edits, length of takes, framing and camera movement of the filmmaking process. Before becoming explicitly Maoist in the late 1960s and 1970s, Godard’s cinema was at least anti-consumerist by default in the use and innovation of low-budget filmmaking techniques and equipment that rendered alienation as the common link between so many of its protagonists. This alienation of characters was nuanced and typically complex, evoked not just in their dislocation from each other but from their product (i.e. the film itself). Where this connects with Linklater is in his appropriation of low-budget techniques for an appropriate and unavoidably Marxist evocation of the slacker collective in

Slacker by means of a film made by and about that very community in a form that reflected its own working practice and ethos. Not for Linklater the thrilling generic spin of

El Mariachi (Robert Rodríguez, 1992) or