Whether hanging out in the real Austin (Slacker, Waking Life and the project known as Boyhood), a metaphorical one (Dazed and Confused, SubUrbia, A Scanner Darkly) or the metaphysical ones of Vienna (Before Sunrise) and Paris (Before Sunset), walking and talking is what characters in the cinema of Richard Linklater do best. Out of several themes that are common to the most emblematic films, including the impossibility of distinguishing between what is real and what is not, dialogue is the most determinant factor in their form, content, meaning, making and marketing. Dialogue is also crucial to the way in which the films are engendered, rehearsed, shot and more often than not find their audience, by word of mouth that is maintained by the extended grapevine of online chat and buyer reviews. On one level, this emphasis on dialogue attests to Linklater’s directorial interest in the theatre and evident enthusiasm for collaborating with actors, but it is also what distinguishes the films from much of American cinema and, within that context, Linklater from many of his contemporaries. The emphasis on perambulatory dialogue also indicates the dialogic nature of films that, as Lesley Speed contends, ‘are radical in their affirmation that intellectual and reflective thought can be pleasurable, an idea that deviates strikingly from the association of American society with “dumbing down” in government, the media, education, science, and religion’ (2007: 101). Thus, this dialogue is oppositional, partly because it resists any hegemonic dictum such as conservative political doctrine or the action-driven template of Hollywood and partly because it serves as a vehicle for the expression, integration and cross-pollination of European intellectual traditions with those of popular American entertainment, albeit primarily in relation to the audiences for art-house cinema. Accordingly, this dialogue-heavy account of the production, distribution and marketing of the cinema of Linklater considers the extent to which Tape, Me and Orson Welles, Before Sunrise and Before Sunset inherit, warrant, express, embody and suffer the notion of art-house cinema.

The artistic potential of film was recognised and exploited in early twentieth-century Europe by movements such as Surrealism and Expressionism. Meanwhile, the presumption of art in relation to American cinema had its precedent in the prestige pictures and literary adaptations of filmmakers such as the ‘independent’ D.W. Griffith, whose

The Birth of a Nation (1915) begins with ‘a plea for the art of the motion picture’. Post-World War II, this conflation of independence with art inspired the emergence of Italian Neo-realism and the French New Wave, the associated rise of film studies as an academic discipline with interdisciplinary potential, the consequent rise of repertory cinemas and the anti-establishment enthusiasm of certain audiences for alternatives to Hollywood filmmaking. The first art-house cinemas in America were ‘exhibition sites [that] featured art galleries in the lobbies, served coffee, and offered specialized and “intelligent” films to a discriminating audience that paid high admission prices for such distinctions’ (Wilinsky 2001: 1–2). Post-war European and Asian cinema played well in New York, Los Angeles and college towns as did documentaries, the avant-garde and the emerging cult films of the midnight movie circuit. In the 1960s and 1970s the notion of art cinema moved away from movements to embrace the practice and product of auteurism, when ‘rising up as a new, emergent culture in reaction to changes in social values, cultural hierarchies, and industrial systems, art cinema shaped itself as an alternative to dominant culture’ (Wilinsky 2001: 3). Linklater recalls the impact of the French New Wave as ‘important to everyone probably, who has made films since then,’

1 but he also credits the art-house cinemas in the university cities of Houston and Austin (as well as his own Austin Film Society) for enabling him to see what was going on in World cinema:

I don’t just leave it to the French: a little bit later and there was what was going on in German cinema, what was going on in England and Japan and America too. Having caught the tail-end of the golden era of repertory cinema when I was first falling in love with cinema meant I could go to a theater and watch double features. All the great films I saw in theaters. Even if it was a 16mm print and there were four other people in the cinema at two in the afternoon, it was still great.

In addition, his awareness grew of what was possible in America:

We don’t call it an American New Wave but I was really inspired by those films too. Shirley Clarke, Cassavetes, Lionel Rogosin: American indies that were just sort of there. Once there was a market there were distributors and theaters, but that was pretty non-existent back in the seventies when I was growing up. Back then there was mainstream Hollywood and there were exploitation films at drive-ins. And if it wasn’t an exploitation film, if it couldn’t be shown at a drive-in, what was it? They weren’t showing Woman Under the Influence at a drive-in. So Cassavetes had to kind of self-distribute his films.

This mix of art-house films from around the world with independent American cinema would have a definitive influence on Linklater. Like many of his generation who were able to study film, he saw the work of amateur, regional, and independent filmmakers such as Cassavetes alongside retrospective screenings of films from the Hollywood studio system that had inspired the French New Wave to champion what they claimed were auteurist filmmakers such as Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks. Linklater was a prime example of those attending art-house cinemas, who sought such ‘distinction from their film-going experiences [that they] searched for films and theater environments different from those offered at mainstream film theaters’ (Wilinsky 2001: 2). However, although the American art-house circuit may have marketed itself and its programming as an alternative to that of the major studios and distribution chains, in truth it has always remained ‘in constant negotiation with the mainstream cinema, a process that has ultimately shaped both cultures’ (Wilinsky 2001: 4). Instead of mostly generic entertainment, art-house cinemas often offered films built from narrative experimentation and ambitious play with form to the extent that, perhaps inevitably, their determined distinctiveness led to an accumulation of so many conventions that ‘by the 1980s this [art] film practice had become almost a broad-based genre in itself’ (Sklar 1993: 508). Non-linear narratives, long takes and enigmatic stares, moody interiors, threatening exteriors and open-ended dialogues about faith, sex and death were to the art house what gunfights, car chases and happy endings were to the mainstream. Art films tended to explore psychological problems without resolution. Their protagonists could thus be inconsistent, while the films embodied the fragmentation that empowered the art film to become ‘episodic, akin to picaresque and processional forms, or […] pattern coincidence to suggest the workings of an impersonal and unknown causality’ (Bordwell 1985: 206). The art film became that of loose ends, unanswered questions and uncertain futures. Yet, as Speed states:

Despite European film’s influence on the generation of American filmmakers that emerged from film schools in the 1960s, the counterculture’s influence on American cinema failed to prevent Hollywood’s gravitation toward the blockbuster phenomenon, from which the high-concept film emerged. (1994: 80)

Nevertheless, the impact of European art-house cinema on independent American filmmakers remained a factor in the form, content, marketing and reception of their films to the extent that it is possible to speak of a dialogue that opened up in the 1960s between American and European filmmakers, one that led directly to the New Hollywood era that was heralded by Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967).

As described by Mark Harris in

Scenes from a Revolution: The Birth of the New Hollywood, Bonnie and Clyde was an attempt to ‘bring a Nouvelle Vague aesthetic to as American a subject as Dust Bowl bank robbers’ (2008: 15). The script by Robert Benton and David Newman combined the generic conventions of the American period gangster film with the aesthetic stylings and ‘live fast, die young’ existentialism of several key films of the French New Wave. Benton and Newman based their script on the ‘studied disregard for the moral and narrative strictures of Hollywood filmmaking’ (Harris 2008: 7) that they identified in Truffaut’s

Jules et Jim (

Jules and Jim, 1962) and were delighted when it attracted the directorial ambition of Truffaut to make a film in America, as well as the bonus but more ambiguous interest of Godard. Incidentally, as a precursor to Linklater’s

Before Sunrise, there were clear Texan, even Austinite origins to this film about boy meets girl, America meets Europe, and mainstream genre filmmaking meets art-house stylings, aesthetics and philosophies. Benton had gone to the University of Texas at Austin in the early 1950s and, as he explained, ‘everybody in Texas grew up with Bonnie and Clyde’ (Harris 2008: 12). With its abrupt shifts of tone, jump cuts, elements of pastiche, emphasis on ambiguous and explicit sexuality and hard-boiled dialogue,

Bonnie and Clyde picked up the baton proffered by Godard’s

À bout de souffle, which had itself taken it from Monogram Pictures, and passed it on to America’s youth. Eventually directed by Arthur Penn,

Bonnie and Clyde revealed the viability and relevance of New Wave stylings to the American public and major studios and thus opened up a dialogue that continues through the cinema of Linklater.

Key points in this dialogue include a preference for dialogue, as well as the affined expression of time through time-images that effect a contrast with the subscription to action and movement-images in the kind of Hollywood product that Bordwell theorised and Paul Cooke describes as ‘action-driven fictions, produced in the “continuity style” which elides the constructed nature of film as a medium’ (2007: 2–3). Slacker, for example and by name alone, promises, nay proclaims an oppositional lack of action, while Dazed and Confused, Waking Life and Before Sunrise are all titles redolent of sleepy hiatus. In truth, however, the cinema of Linklater is rarely still or silent. On the contrary, its supposed ‘idleness’ actually illustrates Samuel Johnson’s contention that ‘if we were idle, there would be no growing weary; we should all entertain one another’ (in Stevenson 2009: 1). However, as Stevenson observes in An Apology for Idlers (2009 [1877]), conflict arises because ‘the presence of people who refuse to enter in the great handicap race for sixpenny pieces, is at once an insult and a disenchantment for those who do’ (ibid.). In comparison with the protagonists of action-driven fictions, slackers resemble what Stevenson described as truants from ‘formal and laborious science, [who] for the trouble of looking […] acquire the warm and palpitating facts of life [and] speak with ease and opportunity to all varieties of men’ (2009: 6). Yet, where the hagiography of an auteurist approach might dress up Linklater’s reputation for independence in the guise of a purposeful truant from industry, the truth is that a dialogue occurs here too. That is to say, the cinema of Linklater is engaged in dialogue with regional, independent and studio-made American cinema as well as European philosophies and film aesthetics, new technologies and the vagaries of marketing and distribution opportunities. This is no tournament of binary face-offs that sets independent cinema against Hollywood or the American intellect against European intuition, but a dialogue that is best understood in relation to the concept of dialogism proposed by Bakhtin in The Dialogic Imagination (2006a [1975]).

Bakhtin argues that ‘all literature is caught up in the process of “becoming”’ (2006a: 5), which corresponds to Henri Bergson’s aforementioned concept of time as something incomplete and eternally becoming. Bakhtin also maintains that literary works may be divided into those that are dialogic and those that are monologic. The dialogic work is that which seeks correspondence with other multiple works and a revisionist approach to what has gone before. Although centered upon literature, Bakhtin’s term extends to language and thought, suggesting that whatever is said must exist not only in answer to what has been said before but also in anticipation of response. As Holquist explains, ‘a word, discourse, language or culture undergoes “dialogization” when it becomes relativized, de-privileged, aware of competing definitions for the same things’ (1981: 427). Dialogism thus dissolves or explodes any attempt at monologue that aims to be authoritative or absolute and so confronts the monotony of all that is monolithic. It is a dynamic process that both demands and enables an endless revisioning of the world; but it is not merely intertextuality, which too often suggests that everything has already been said and done. Rather, it expresses something of an optimistic response to existentialist challenges. In relation to the cinema of Linklater, the conceit of a film as a dialogic work that is itself constructed from a collaborative dialogue amongst its makers and which features dialogue between protagonists as its primary mode of expression denotes a particularly meaningful coincidence. In respect of its commercial prospects this points to what the filmmaker admits is a default and problematic marketing position for many of his films: ‘If it’s too smart it becomes an art film.’

Alongside

Waking Life, perhaps the most experimental and self-consciously smart film amongst those directed by Linklater is

Tape, an adaptation of screenwriter Stephen Belber’s own single set, one act, three character play that was financed by the New York-based InDigEnt (Independent Digital Entertainment) company that provided small budgets on a profit-sharing basis to filmmakers willing to embrace the potential and limitations of shooting on digital video.

2 The impetus to filmmaking and film movements from new technologies like this is a recurring phenomenon, although Linklater’s first experience of digital filmmaking was a cautionary one:

You can now just point and capture things, and that’s a great thing, obviously, for the world and communication, but it doesn’t necessarily equal art. […] There’s a skill involved, and one of the first things people find out in filmmaking is that the skill isn’t being able to push a red button on a camera. The real skill is in storytelling. (In Savlov 2009: 41–2)

Tape tells the tale of the reunion of drug dealer Vince (Ethan Hawke) with high school friend Jon (Robert Sean Leonard), a documentary filmmaker who may once have date-raped Vince’s ex-girlfriend Amy (Uma Thurman), an assistant district attorney who turns up to question the veracity and interpretation of the remembered events. However, as Geoff King describes, ‘the aim, for Linklater, was to create something akin to a collage effect [that was] thematically motivated’ (2009: 120). Although granted autonomy by InDigEnt, the challenge for Linklater was to shepherd a collective endeavour to fruition without overstating his authorial responsibility. Thus, in addition to filming with digital cameras and adhering to a specific time-frame,

Tape was also somewhat experimental in its negotiation of authorship. As with

Slacker, Dazed and Confused and

SubUrbia, there was a cacophony of voices both onscreen and off, with Belber, editor Sandra Adair and the cast all arguing the work into existence. In particular,

Tape was made in accordance with the kind of dialogue and collaborative working practice that Linklater coordinated at the start of his career:

Yeah, as soon as I started working with other people, which was Slacker, that’s exactly how we did it. I had these notes or texts, I would hand them to people and say: ‘Lets read it!’ And then they would start talking, taking notes, just a very collaborative thing.

Like Hitchcock’s Rope (1948), Tape involves the construction of ‘the specifically filmic […] “between four walls” chronotope’ (Stam 2000: 205) and the claustrophobia of its theatrical origins is exacerbated by Stephen J. Beatrice’s four-walled set of a seedy Michigan hotel room. Set entirely within the time-frame of the film’s 86 minutes, Tape leans towards experimentation and the ‘smartness’ of art while holding on to the mainstream, for, as a melodrama styled around the recriminations of a small number of people who challenge each other’s memories, it is not unlike a particularly claustrophobic drawing room whodunnit. Linklater had directed theatrical productions while at university and professes great admiration for the British playwright Tom Stoppard, whose witty dialogue often addresses philosophical concepts and conundrums. His Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead (1966), for example, deals with two minor characters from Shakespeare’s Hamlet who idly ponder their fate beyond the original work but find themselves equally sidelined and rendered powerless by their reality. Rather than take action, the two slacker courtiers kill time with absurdist, existentialist dialogue that would fit well into Slacker, SubUrbia, Waking Life, Tape and even Before Sunrise and Before Sunset. Similarly to Stoppard, the chance to explore existentialism in the shaping of a basic text like Tape into situation, character and dialogue is what attracts and inspires Linklater:

It’s always been my instinct to loosen it up with the actors and let them reimagine their characters. I tell actors: ‘We’ve got to take this apart, find the beats!’ My nightmare of an actor is someone who doesn’t want to think much about it or work it through and personalise it and make it better. Even if I’ve written every word of the script and it happened to me, even if it’s very personal to me, I’m not attached to the character. It’s not me. This is the great thing about art. This is the beginning of it, but the end of it will be you. I’m not that beholden to recreating my own life specifically. I like it as a jumping off place but I’m really more interested in what we can come up with, getting to some level that’s not pre-ordained.

Despite the potential for diversion and digression in this creative process,

Tape is fittingly a film with a one-track mind. Whip pans between the actors, stark lighting and the kind of over-emphatic editing allowed by the Final Cut Pro software all conspire to pin Vince and Jon to the grimy walls. As the confined space and combative dialogue make it impossible for the digital cameras to take in the whole scene and the fluctuations of expression as might occur in the theatre, the editing hurtles from face to face in an attempt to keep up with the characters’ evolution. Leonard is ingratiating and insufferable as the character whose moral superiority turns to arrogance, while Hawke is magnetic and repulsive, alternately strutting and cowed. Their discussion turns into interrogation and the act of remembering becomes their punishment for forgetting. Amy turns up fifty minutes in to confront the men with the redundancy of any confession to her present situation and so the meaninglessness of any apology that relates only to an irrelevant past. For a film with such an emphasis on time in both its narrative dependency on a past event and the time-frame of the present encounter,

Tape finds no curative quality to its passing. Instead, the lack of any resolution to its intrinsic dialogue corresponds to the conjoined notions of time and the dialogic work as things that are constantly becoming. Moreover, the multiple, contradictory perspectives of the characters and the shifting debate over which of the three can lay claim to ownership of the ‘historical’ past denotes the previously analysed Cubist notion of form and content in the film’s expression of time and its remembrance.

Koresky calls

Tape the ‘polar opposite’ of

Waking Life, seeing ‘debate without philosophy’ (2004b) as its failing, which does hold true in comparison with the cinema of Eric Rohmer, for example, whose similarly intense, dialogue-driven films often feature a melange of neurotics, romantics and pragmatists in mostly playful, ironic, melancholic badinage that rarely fails to ferment philosophical debate. However, the true importance of

Tape in the cinema of Linklater is that it comes between the more reverentially Rohmeresque

Before Sunrise and

Before Sunset in a much more meaningful manner than the brief animated interlude shared by Jesse and Céline in

Waking Life. If

Before Sunrise corresponds to the idealism and potential of youth and youthful sexuality,

Tape interrogates regret for wasted time and inexact recollection. It is therefore the halfway point on a journey to

Before Sunset, which investigates the possible revival of idealism and the recapturing of all that potential. The space between

Tape and

Before Sunset is what Koresky calls ‘the uphill journey from emotional retardation to a spiritual solace, from digital-video grime to 35mm splendor’ (ibid.).

Tape might be the visit home made by a young American played by Ethan Hawke between his visits to Vienna and Paris, for it is not merely a pause or digression but an exploration of the angst that occurs when separated from the idealism of

Before Sunrise and the reclaimed potential of

Before Sunset. As such it connects with and perhaps in part explains this enthusiasm for experimentation with film form, practice and technology that Linklater expressed in 2001, firstly with the digitally-filmed then rotoscoped

Waking Life and then with his assault on the pre-fabricated limitations of the time-frame, single tiny set and theatrical text by means of hand-held digital cameras and editing on an Apple computer of

Tape. Together, as Roger Ebert surmised, these two films served as ‘instruction manuals about how to use the tricky new tools’ (2001). Consequently, they extend the dialogue with film history and future film, not only by exploring the new dynamics of digital filmmaking, rotoscoping and other new technologies but in the way the emphasis on dialogue, character, time and the

durée of the

dérive draw on ‘the SI [Situationist International] and other European movements to posit an avant-garde ancestry for recent American independent film’ (Speed 2007: 104). That is to say, on the one hand

Tape is a test drive of digital gadgets, while on the other it is a coked-up Rohmer that suggests how ‘Linklater’s allegiance to the European avant-garde explores what American cinema might have been if market-driven, high-concept films had not achieved dominance’ (ibid.).

Tape was picked up for distribution by the independent Lions Gate and won the Lanterna Magica Prize at the 2001 Venice Film Festival as well as a nomination for Thurman as Best Actress at the Independent Spirit awards. Founded in 1984 and originally called the Friends of Independents Awards, the ‘Spirits’ were renamed in 1986 partly out of the aforementioned impossibility of categorising any film as truly independent. Instead, the ‘spirit’ of independence was celebrated then and since in awards made to films that arguably still ‘felt’ independent despite their distribution by such parent companies as Paramount (e.g. Brokeback Mountain [Ang Lee, 2005]) and Fox (e.g. Juno [Jason Reitman, 2007]). The matter of independence was thus ironised, which nevertheless fuels Speed’s observation that:

The studios in recent decades have absorbed modes of filmmaking that were previously associated with independent production [to the extent that] the contrast in Linklater’s career between market-driven entertainment and contemplative art cinema can be understood in relation to [this] blurring of the distinction between independent and mainstream American film since the 1980s. (2007: 99)

This blurring is also a dialogue between independent and mainstream cinema involving technologies, demographics and systems that are in constant flux. As Linklater contends:

Distribution and marketing have changed incredibly. The bottom line is that marketing has become so expensive. The radical thing that freaked everybody out was releasing movies on DVD around the same time as the cinema release. This gap business of either going to the movies or waiting six months for the DVD, that seemed like such an affront, such a threat to the theater-going experience; but I didn’t really look at it that way. Different markets. By the 1980s it was already a different game really.

However, in relation to the recent fostering of independent films by the distribution wings of the majors, Linklater is less bothered by the irony of the matter than by prevailing cynicism:

The studios have now abdicated that role completely. They’re not interested in art. They’re in a business that precludes something that might resonate with adults or anybody with a certain sensibility. I’ve seen that gap just get wider and wider and wider but at least they’re really honest now. It’s like, ‘We’re not in that business’, you know? A lot of those distributors have gone out of business already. Two of my movies in the 1990s were distributed by Warner Independent. Well, ‘big Warner’ just said: ‘Ah, let’s just close that division. It doesn’t make much money, if anything. It’s kind of a break-even business. No one’s going to complain if that just goes away and we just concentrate on

Harry Potter.’ So we lost another outlet. That world was under attack anyway, and then the bigger economic situation in the world has been a second tidal wave right through it. So right now there’s just nothing left.

In forging ahead with low-budget films shot on digital video, the InDigEnt enterprise and Tape in particular challenged the assumption that the audience for art-house cinema was different from that for the mainstream. Generically speaking, Tape is an intense hybrid of melodrama and thriller that for all its formal and digital experimentation remains conversant with the conventions of the theatre. At the same time, however, its use of digital technology points to new modes of reception for art-house and independent films that extend from home-viewing on DVD, Blu-ray, Netflix and computer to inexpensive digital distribution and projection. Linklater sees this use of digital technology as essential to safeguarding, enabling and extending the territory of independence:

I was talking to Steven Soderbergh about this and he said, ‘I can’t wait until there’s digital projection because all distributors do is ship prints and collect money.’ And then if shipping the prints wasn’t the deal, if the theaters could just download your digital film, even if you shot on film, they could project it digitally, which looks great and then you really don’t need to make your separate deal with your distributor. All distributors are is kind of a middleman between the film and the audience anyway. You could almost cut him out.

As Linklater explains, this kind of cheap, direct distribution changes the process of marketing and, moreover, removes any middleman from the dialogue sought by filmmakers with their audience:

Anyone can come up with an ad, a poster and a trailer if you really want to go all the way. Why would some guy spend 35 million of his own money and then give the film to some small company that spends a million distributing it? It’s just a matter of time before the guy who spends 35 million says, ‘They didn’t even care about it! I could have hired three people also!’ So that’s what’s happening right now.

This potential boost to the viability of independent and art cinema may also extend a filmmaker’s responsibility towards distribution and marketing. Linklater welcomes this development in particular:

I haven’t had too many good experiences with marketing. You have no control over marketing. It’s frustrating. Filmmakers are control freaks and, collaborative as I am, I’m still really specific about what I’m going for. [A film] can have a horrible film poster, and for me, who knows the history of film posters, to have a horrible film poster for your movie, I cannot explain to you how heartbreaking that is.

In approaching the grand chaos of this dialogue with marketers, producers, investors, distributors and the audience, Linklater and any film of his might be best understood in relation to Lyotard’s ruling that ‘a self […] does not amount to much, but no self is an island; each exists in a fabric of relations that is now more complex and mobile than ever before’ (1999: 15; emphasis in original). Linklater is thus a participant in a dialogue resembling this complex and mobile fabric of relations that involves a film and its maker with new and old forms of industry as well as with diachronic and synchronic film histories, the tradition and subversion of culture, and revised forms of production, distribution and reception. Nevertheless, his ambition is tempered by caution:

Most people who come up to you and say they liked your movie watched it at home. You just have to accept that. Every filmmaker in the world has this idealistic notion of, ‘Oh, how nice they were sitting in a huge theater watching it on a big beautiful screen!’ But they weren’t. It used to not bother me much at all if people were bootlegging a bad video back in the video days when things were being passed around. Once that was happening, I was like, ‘Oh, that’s good, it means people want to see it.’ When it was hand to hand it was good news. But now with the viral thing you’ve got to be a lot more careful.

In ensuring that the dialogue keeps pace with new technologies and evolving definitions of independence, Linklater was especially keen to learn how to distribute his own films from the USA and UK release strategy of Me and Orson Welles, an adaptation of a 2008 Robert Kaplow novel about an ambitious young man’s involvement with Welles’ Mercury Theater Company during the 1937 New York production of Julius Caesar. The film had its premiere at the 2008 Toronto Film Festival but its release was delayed so that Linklater could explore new forms of distribution:

After Toronto we could have taken offers, but that delay was really okay. That at least showed us, right, we’ve got be smart about this. For those of us who worked so hard on this film and cared so much about it, we really had bigger ambitions for it. When it comes out, I want it to have a bigger and better chance. There’s new distribution that’s coming about and I’m going to learn a lot about how this goes. I’m more involved this time than I ever have been with the release of any of my films since Slacker. I thought it was time to jump back in there and pay a little more attention because it seems like such a crucial time. And it has so much to do with social networking that I’m going to have to use that part of my brain that isn’t the most fun, but it just seems like it’s an essential time to be a part of the new ‘whatever-it’s-gonna-be’. Something’s definitely over but it hasn’t been completely mastered yet.

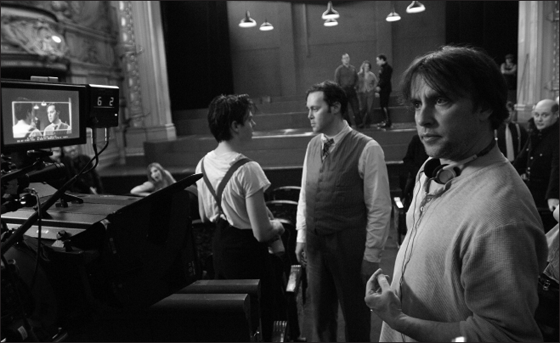

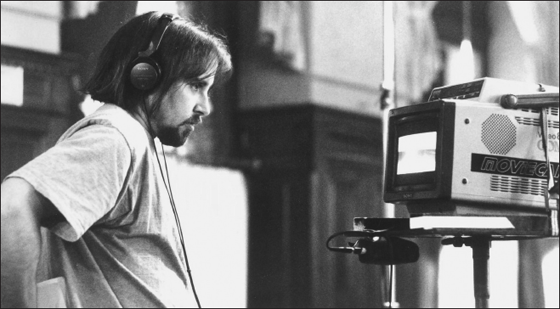

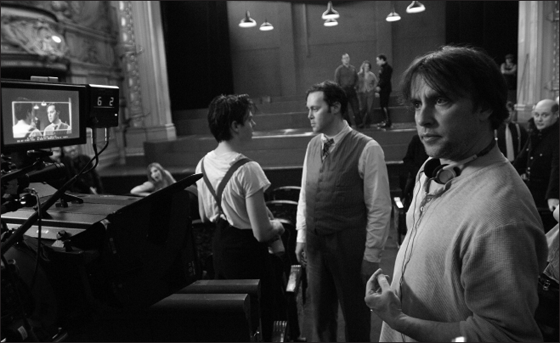

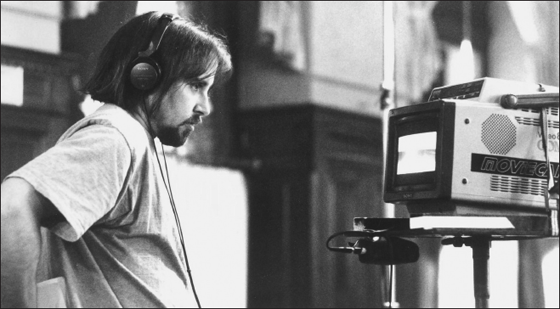

Richard Linklater directing Zac Efron (right) and Christian McKay in

Me and Orson WellesAlthough Me and Orson Welles was not self-distributed, it was handled by a new company called CinemaNX set up by the Isle of Man Media Development Fund that had financed its production. The film opened in November 2009 through Freestyle Releasing, backed by a campaign by former New Line marketing executive Russell Schwartz’s Pandemic Marketing, with Hart/Lunsford Pictures funding the promotional costs. CinemaNX was cautious, selling the DVD rights to Warner Brothers in a deal brokered by Cinetic Media (and an exclusivity deal to the Tesco supermarket chain in the UK) but, as Linklater explains, ‘holding back too. Instead of giving it to the distributor for a million bucks they want no commitment beyond a certain level. They believe in the film.’ As a period film with a theatrical setting, Me and Orson Welles seems a particularly contrary example of independent filmmaking, which tends to favour contemporary realism. At the same time, however, with its teen-dream star (Zac Efron) and generic conventions it is an unlikely inhabitant of the art house. Linklater agrees:

Yeah, its weird we’re even in the rubric of independence. To me this feels like a studio type of film: PG13, fairly family friendly, not inaccessible. And yet the ground has sort of shifted enough that Hollywood is not making this sort of film anymore.

The dialogue thus falters, until new directions appear. As Linklater contends:

There are two markets for

Me and Orson Welles. There’s an art film market and there’s this ‘because of Zac [Efron]’ and the youthfulness of the audience and the movie. I’m taking that audience for granted, the ones who’ll read reviews; but you really have to see to the teenage audience and for that you really have to use social networking sites. The studio said that audience wasn’t going to go, but I disagree. You want to be able to say, ‘Fuck you, you’re wrong!’

Thus the dialogue extends naturally to chat rooms, social networking sites, Twitter and whatever else comes along.

3Most pointedly, however, Me and Orson Welles may be appreciated as a dialogic work for the manner in which it relates to Welles, who Linklater describes as ‘the progenitor and the martyr’ of independent filmmaking:

That’s how the US looks at him and I think he took on that role to a large degree. There’s a sadness that he didn’t get a film made a year for twenty-five years, but what’s great is that he made what he did. Americans tend to look at Welles like he was something tragic [but] I was refreshed being in the UK and I saw a European attitude to him, which was more about, ‘Well gosh, he made however many masterpieces, arguably five or seven in so many different decades.’ Name a playwright who had that kind of longevity! That’s a successful career! Sure he struggled, but that’s not so bad. That’s not a tragic life on the surface. Anyone would sign up for that. And yet it’s not enough. America in particular tends to chew up and spit out its artists.

The dialogue with Welles that Me and Orson Welles upholds is also one that resonates down through the history of independent filmmaking in America:

Honestly, he’s a guy out of time, you know. He would have done so much better if he’d been born however many years later. By the time the 1980s and 1990s came around he would have been like an Altman character who could have gotten funding worldwide for his little Shakespeare adaptations. That would have been great. But when he was living, his struggle just wasn’t possible. So it’s heartbreaking when you see a masterpiece like his Othello, which I think is the greatest Shakespeare adaptation ever made. If ever proof were needed that this guy was just an absolute pure filmmaking genius, just watch Othello. And Chimes at Midnight, which is really even more obscure. Those two are just brilliant. To know that they were so neglected, so forgotten. The way he financed them himself, the way he put them together, it must have been tough for him. Meanwhile Olivier is winning all the Oscars for Hamlet, you know, which really isn’t all that cinematic. It must have been tough for Welles, who had been at the height of his acclaim, to know that he had done something so great and just see nobody give a fuck. It really must be humbling.

And what, if any is Welles’s influence on the struggle of contemporary indie filmmakers?

The struggle’s the same. It’s just so much easier now though. What Welles was going up against in the forties was still the full-blown studio system, which I love. But Welles was too enlarged of a talent to fit in. Welles barely got his RKO premiere in the day, though he was totally willing to take the film himself and show it in tents. There’s a parallel world where Welles took the film himself around the country and created a sensation everywhere he went with his new film and became the P. T. Barnum of movies. And then he became this renegade who profited from that and had his own alternate film universe that was Orson Welles.

The proximity of this alternate reality to the one that Linklater collaborated on creating with the independent production and distribution of Me and Orson Welles exemplifies how the dialogic work for the cinema is not only indicated by intertextuality but by influence and resonance in all aspects. For Linklater the experience of making this film was ‘completely refreshing just to hang out with the early Welles’, even though the experience ‘goes against the biggest Welles theme of all, particularly in [Citizen] Kane, which is the unknowableness of the individual’. In terms of aesthetics and film style, Linklater claims he ‘really, intentionally, never tried to get Wellesian. That would be ridiculous to shoot it like Welles would have because Welles wasn’t a filmmaker at this point.’ Nevertheless, the film does feature a curious indication of dialogism when an extra in the audience for Julius Caesar is made up to look like Gregg Toland, the cinematographer of Citizen Kane (1941), for, as Linklater claims, ‘that marriage is born right there and it’s a key moment in film history’. Most significantly, however, the dialogic nature of the film is the manner in which Linklater, like Welles, had to go to Europe to get film funding: ‘Yes, that’s very Wellesian. Maybe it’s the Welles curse, you know. Maybe this film is ultimately Wellesian.’

Nevertheless, in Linklater’s view the dialogic work and its connection with an audience is most often forestalled by marketing executives. The problem was that post-Toronto offers of distribution came tied to limited marketing strategies:

Ultimately you have multiple audiences and that’s kind of anti-Hollywood right now. They want to hear that you have one very specific audience that’s going to love it, even if that audience is 14–17-year-old girls or 17–21-year-old boys, because it’s easy to market. The last thing they want to hear is that everyone might like the film, which is the case here.

According to Linklater, the cost of marketing is ‘one of the big burdens of the modern cinema, not that movies cost so much but that they’re so expensive to market, especially with indie films’. Thus, although declarations of independence and art can be shields as well as badges, the reduction of a film’s interest and worth to either term in its marketing potentially limits a dialogue in which Lyotard exhorts ‘the interlocutors [to] use any available ammunition, changing games from one utterance to the next’ (1999: 17). The eternal ‘becoming’ of this dialogue thus includes the evolution of terms as noted by King:

The term ‘mainstream’ can easily become a rhetorical construct that obscures numerous forms of differentiation […] as can other terms such as ‘dominant’, ‘commercial’, ‘alternative’, ‘distinctive’, and so on. [It] is also an

operative construct, a discursive category in widespread use, explicitly or implicitly, in the articulation of a range of points of distinction [and] often taken as a reference point against which other forms are defined. (2009: 33–4; emphasis in original)

The same is true of ‘independent’ and ‘art-house’, which both suggest a certain elitism in the marking of actual territory, while King ultimately admits that a formulation such as his own ‘Indiewood’, which he defines as ‘an area in which Hollywood and the independent sector merge or overlap’ (2009: 1) is also one that ‘exists as, or has become, a largely marketing driven niche’ (2009: 274). As King concludes, all these terms ‘become vague to the point of lacking much capacity for closer discrimination’ (2009: 237). However, it is precisely this blurry vagueness that inspires rather than stalls the need for dialogue that Lyotard likens to a war that ‘is not without rules, but the rules allow and encourage the greatest possible flexibility of utterance’ (1999: 17).

As a dialogic work, the cinema of Linklater, like that of many filmmakers, carries on a continual dialogue with other films and filmmakers. For example, the centrifugal and centripetal energy of this dialogism is ably rendered in Me and Orson Welles. ‘Wouldn’t this make a great story? Two people meeting like this. Nothing more,’ exclaims Gretta (Zoe Kazan) to Richard (Zac Efron) in an affectionate nod towards Before Sunrise, although the dialogue and its expression of the spirit that infuses the cinema of Linklater come intact from Kaplow’s novel:

‘And what happens?’

She looked confused. ‘What do you mean “what happens”? Nothing happens. Why does something have to happen?’

‘No, I meant…‘

‘The whole story is what I told you. […] You know, mostly mood. The girl goes to the museum feeling blue. She thinks about time and eternity, and then she feels a little better.’

‘Oh…’

She got defensive. ‘There’s no action in it, if that’s what you’re looking for. God, can’t you just be walking down the street, and suddenly you’re happy? […] Well, stories can be like that too. Why does everything have to have a big plot? All that melodramatic garbage?’

‘Hey, I’m on your side, Gretta,’ I said. ‘I agree with you.’ (2008: 126; emphasis in original)

Not only does the intrinsic Richard agree with her but the extrinsic one (Linklater) does too, who further extends the allusion throughout his own work and in this specific adaptation to the influence of Godard by ending the scene with Gretta and Richard running from the museum chased by a guard in a reprise of the scene from

Band à parte in which Odile (Anna Karina) leads Franz (Sami Frey) and Arthur (Claude Brasseur) on an attempt to break the world record for running through the Louvre. For Linklater, ‘art house cinema was always European film, whatever was the latest film from France or Germany or Russia, you know’. His film-going, his university education in French and Russian literature and his curating of the Austin Film Society all engendered the dialogue that shapes his work as writer, co-writer and director and is especially loud in relation to

Before Sunrise and its sequels.

Before Sunrise is particularly emblematic of the dialogic and dialogue-driven cinema of Linklater because its production was ‘always about the process of its own making, a process that never stopped and was always open for new thoughts and inspirations’ (Linklater 1995: v). However, the cinema of Linklater is not aimed at curtailing the globalising force of the raucous action blockbuster with a calming whisper. On the contrary, it is simply the kind of cinema that enables a more complex ‘notion of a “dialogue” operating on a number of at times competing economic, aesthetic or philosophical levels’ (Cooke 2007: 8). The competitive economic level is based on the ratio return of profit to cost by which, in simple terms, cheaper films can get by on lower returns that still ensure the employment of those involved in their making and even allow for such things as a sequel. The occasional crossover success of an ‘indie’ to the mainstream is always welcome but, on the whole, independent filmmakers survive by keeping their costs down. For Linklater this has meant investigating the possibilities of new digital filming, editing and distribution technologies as well as cutting corners, improvising and getting stars such as Bruce Willis in

Fast Food Nation to work for a reduced wage. This traffic goes both ways, however, with Linklater willing to work for a salary or fee within what he calls ‘the full-blown studio system, which I love’. In addition, this literal ‘crossover’ is also Linklater’s embodiment of a dialogue, one that prompts Speed to argue that ‘Linklater’s crossing of boundaries among experimental, independent, and entertainment cinema is utopian in its eschewal of any absolute filmmaking approach’ (2007: 105). As previously noted, Linklater concurs: ‘I would like to have been Vincente Minnelli or Howard Hawks making a film or two a year in the studio system.’ On one level, this admission suggests his subscription to theories of auteurism:

We know who had the great careers in and around the system – Wilder, Huston, all the Europeans that came over like Lang – and I think you had to sublimate your own ego on the surface. Secretly you’re making your film, but at least on the surface you had to show that you’re being a company man.

However, such a traditional view of auteurism is illogical and self-defeating in the type of collaborative production process required of an independent film and those of Linklater in particular, where there is no rigid hierarchy to subvert. Linklater’s part in the dialogue between studio and independent filmmaking leads Speed to conclude that ‘his career’s juxtapositioning of experimental and formulaic films suggests a utopian view of film production as accommodating diversity without negative tension’ (2007: 104). More than this, however, Linklater is sometimes able to reconcile any contradiction by blurring the juxtaposition in a single film. At least on his own terms, for example, Before Sunrise is a Minnelli-esque musical.

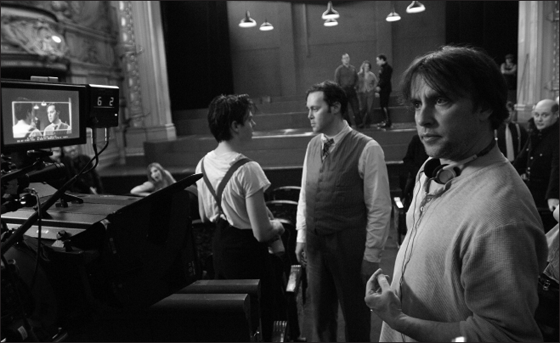

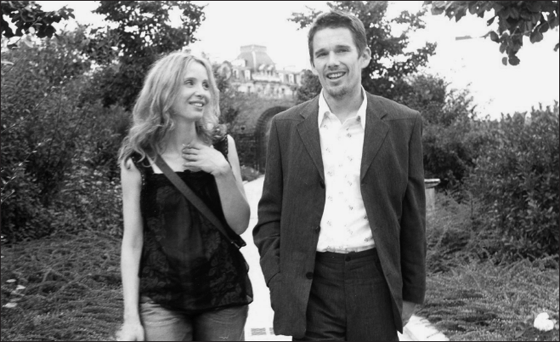

Richard Linklater, Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy rehearsing

Before SunriseBefore Sunrise is not the first musical without singing or dancing. Godard claimed his Une femme est une femme was ‘a neo-realist musical … a complete contradiction’ (in Anshen 2007: 93) and that film’s wilful, neurotic Frenchwoman Angela (Anna Karina) is a fitting forerunner of Céline (Julie Delpy). What Before Sunrise and Une femme est une femme share is an enthusiasm for all the conventions of a Hollywood musical, including the segues and cues, the romantic tension, the sublimation of sex into song and dance, the way the numbers unite a couple or a community and the way a film is structured according to the various types of song, without ever breaking into any artificial musical number. In this they are aligned with James Monaco’s view that ‘abstractly, film offers the same possibilities of rhythm, melody and harmony as music’ (2000: 55). However, neither is Before Sunrise the only all non-singing, all non-dancing musical in the cinema of Linklater, for the accumulative effect of Slacker’s supposedly unique structure is also musical. Slacker may even be appreciated as an epic ‘passed-along’ song of a generation that shares what Jane Feuer terms the ‘socio-economic alienation’ (1993: 2) of the Hollywood musical that makes up for ‘the breakdown of community [by] the creation of folk relations’ (1993: 3). In common with naturalistic musicals, Slacker ‘cancels choreography’ (Feuer 1993: 9). Instead, its ‘passed-along’ form and narrative embody Bakhtinian principles of the carnival by ‘employ[ing] film techniques such as the travelling shot and the montage sequence to illustrate the spread of music by the folk through the folk’ (Feuer 1993; 16). The only difference is that the ‘music’ in this carnival is the dialogue. The same is true of Before Sunrise, which is structured around a series of dialogues that are numbers: duets, in fact, punctuating the narrative of a nocturnal dérive around Vienna of a young American abroad and the French girl he persuades to walk and talk with him until dawn.

The dialogic nature of

Before Sunrise is well illustrated by this allusion to the Hollywood musical genre whose greatest exponents were MGM producer Arthur Freed and director Vincente Minnelli, who together created

The Clock, which Linklater screened for Delpy and Hawke during the making of

Before Sunrise, because both films adhere to the brisk boy meets girl dynamic of the musical genre even if their walking and talking never turns into song and dance. The films may have different attitudes to destiny: in

The Clock Alice Mayberry (Judy Garland) and Corporal Joe Allen (Robert Walker) are fated soulmates, while Jesse and Céline are the authors of their own togetherness (see MacDowell 2008). However, both resonate with the emotions of classic melodrama that in

Before Sunrise are also felt in relation to the Viennese setting and the long, eloquent takes with a mobile or static camera that recall

Letter from an Unknown Woman. Ophüls’ intricate long takes expressed the journey or pattern of life, whereas for Robert Bresson they tended to indicate its destiny. In addition, for Linklater, ‘Truffaut is the master of the planned sequence. You’d plan it all out, move the camera. You’d realise you didn’t want or have to cut it a lot. You could spend half a day on one three-minute scene.’ Thus, such shots as the five-minute take of Jesse and Céline on the tram or avoiding eye contact in the listening booth evoke a diffidence towards narrative that is rendered by the snub of going with the flow and just drifting with the movement and dialogue of the actors, whose temporalised existence is expressed in the guise of the time-image. ‘Yeah, I just love it!’ says Linklater:

You know, to me that’s the purest cinema, the André Bazin idea of pure cinema. There’s no cutting, there’s nothing else. It forces you into the reality of the moment. You could if you wanted to cut away, but I like this way of making film. You see it in Preston Sturges too. Go back and watch Sullivan’s Travels and you’ll realise, ‘Holy crap, the whole scene is like one take!’ You wouldn’t know it because the camera’s moving around and within the frame it’s got so much energy. It’s like a musical.

Before Sunrise also references The Third Man (Carol Reed, 1949) with the ferris wheel in the Wiener Prater, while Jesse is but the latest in a long line of cocky but sensitive Americans abroad, including Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) from The Third Man (and Welles too as Harry Lime, for that matter) as well as Jerry Mulligan (Gene Kelly) in Minnelli’s An American in Paris (1951) and Joe Bradley (Gregory Peck) in Roman Holiday (William Wyler, 1953). The film’s dynamic also recalls Two for the Road (1967) directed by Stanley Donen, who like Minnelli was a master of the musical and capable of transposing its particular structure of numbers alternating with narrative to that of the dialogues between Joanna (Audrey Hepburn) and Mark (Albert Finney) on their bittersweet journey through the south of France. These films alone refute Paul Schrader’s view that ‘American movies are based on the assumption that life presents you with problems, while European films are based on the conviction that life confronts you with dilemmas – and while problems are something you solve, dilemmas cannot be solved, they’re merely probed’ (in Elsaesser 2003: 44). As Elsaesser observes:

[Schrader’s] assessment is not that far removed from the view of Gilles Deleuze, who in his Bergson-inspired study of the cinema proposes a more dynamic, and self-differentiating version of Jean-Luc Godard’s old distinction between ‘action’ and ‘reflection’ [,] contrasting instead the movement-image of classical cinema with the time-image of modern cinema. (2003: 44)

However, Schrader’s dialectic model is an elitist binary equation that fails to take into account the European mainstream and the American art house and is consequently rendered redundant by the dialogism of a film such as Before Sunrise, which responds to the generic conventions of the melodrama and the musical as much as it blurs them with its enthusiasm for European philosophy and dialogue.

Initially, the problem-solving obsession of Schrader’s American ‘movies’ is illustrated when Jesse resorts to a rational, intellectual (American) argument incorporating persuasive theories of time travel to convince Céline to do things. He tells her that getting off the train in Vienna with him is a jump back in time from her future self. The gambit works, but it is also countered in the original script by Céline’s intuitive, spontaneous (European) response and her subsequent probing of his dilemma: ‘Is this why you tried to get me off the train? Competitiveness? To make sure the guy behind you didn’t pick me up?’

4 Thereafter, the dialogue gradually blurs, even subverts any distinction between the problem-solving intellect of American ‘movies’ and the dilemma-probing intuition of European ‘films’ by showing repeatedly how Jesse’s capacity and need for reflection (‘I feel like this is some dream world we’re walking through’) is answered by Céline’s penchant for intellectual cynicism: ‘Then it’s some male fantasy: meet a French girl on the train, fuck her and never see her again.’

The existential fears that unite Jesse and Céline, who claims to ‘always feel like I’m observing my life instead of living it’, are ultimately rebuffed by the potential of their romance, which emulates those films of the French New Wave that posited the individual as self-determining in matters of the heart. In getting off the train together in Vienna and in separating at the end, Jesse and Céline take full responsibility for their actions instead of succumbing to any preordained role or convention. Thus their shared experience responds to the slacker ethos in its justification of the journey as a kind of exile. In the published script there is an excised section of dialogue on the train in which Jesse explains: ‘That’s what I like about traveling. You can sit down, maybe talk to someone interesting, see something beautiful, read a good book, and that’s enough to qualify as a good day. You do that at home and everyone thinks you’re a bum’ (Linklater and Krizan 2005: 13). His observation also tallies with how, as Céline observes of Seurat’s human figures, characters in the cinema of Linklater ‘always seem so transitory’. Their physical and spoken exploration of the slacker ethos makes tangible the many alternative realities made possible by their determinism: ‘If I was asked right now to marry you or never see you again, I would marry you. I mean, maybe that’s a lot of romantic crap. But people have gotten married for a lot less. I think we’d have as good a chance as anyone else.’

The immediate, enlightened intimacy of this couple ‘on the run’ from reality expresses an affinity with the protagonist couple of Godard’s

À bout de souffle, wherein (although the gender roles are switched) Frenchman Michel affects American intellectual pretension but ultimately succumbs to a romantic view of his own gangsterdom, while the American Patricia tries imitating French style and intuition but is finally revealed as a pragmatist. When Godard reconnects with the fleeing lovers in

Pierrot le fou he expresses a particularly bitter response to the intellectual arguments put forward by America for its globalising business and military avant-garde, blaming it for the division of intellect and intuition as expressed in the remnants of the relationship between Ferdinard and Marianne: ‘I can never have a real conversation with you. You never have ideas, only feelings.’ Jump cuts from

À bout de souffle to

Pierrot le fou to

Bonnie and Clyde to

Before Sunrise suggest an accumulative persona for Céline, not least because Delpy made her main acting debut aged fourteen for Godard as Wise Young Girl in

Détective; but in truth the allusion was unplanned because she got the role by auditioning. ‘I bet on the smartest girl I met,’ says Linklater, who based

Before Sunrise on ‘one very fun evening in Philadelphia’ with a woman he met in a toy store.

5 Furthermore, as Linklater explains, the concept went through various incarnations and nationalities before he settled on the eventual dynamic:

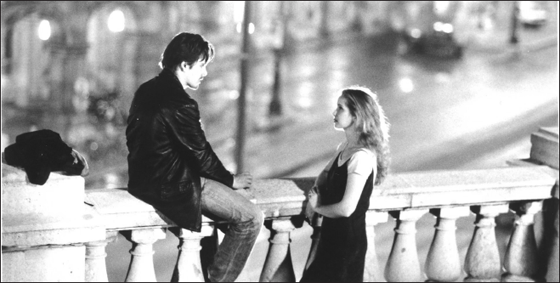

‘You’re in my dream and I’m in yours.’ Jesse (Ethan Hawke) and Céline (Julie Delpy) in Before Sunrise

I met Julie [Delpy] really early and at that point I didn’t know if it was going to be an American man and an international female or an American female and an international man. You know, I knew it was going to be cross-cultural, but it could have been switched if I hadn’t found the right international female. So I interviewed a lot, just trying to piece it together and see which way it would go.

Linklater met Hawke after seeing him in a play featuring Anthony Rapp (Tony in

Dazed and Confused) and invited him to an audition/rehearsal in New York. Linklater says he was ‘looking for intelligence, seeing who was creative, seeing who would collaborate with me, not just ask, “What are my lines?”’. Finally, because he believed ‘the script needed to be completely re-imagined through the two people’. he chose Hawke and Delpy because ‘a lot of actors don’t have that imagination, they’re not on the creative, collaborative process with you’. This confirmed the central dynamic as that between an American man and a French woman, while the film’s location was switched from San Antonio, sixty miles southwest of Austin, to Vienna, capital of the Republic of Austria, which Linklater had visited for its film festival in November 1993. At the time he noted its affinity with Austin: ‘Vienna had a lot of people who were just hanging out. It kind of reminded me of Austin in a certain way. [They were] café people, really smart people. It felt like a big college town, very laid back’ (in Hicks 1995).

The collaborative process that Linklater sought with co-screenwriter Kim Krizan and his actors prioritised dialogue between the filmmakers as the key to making a script from a series of dialogues that had been worked up in rehearsal. Before Sunrise was not simply the result of ‘a certain creative evolutionary process […] in which everyone involved contributed to the essence being portrayed on screen’ (Linklater and Krizan 1995: iv) but, correlatively, was a film about ‘people who verbalize their inner thoughts […] and thus reveal themselves to each other’ (ibid.). In other words, both the offscreen and onscreen discussions belonged to a single dialogue to the effect that, as Robin Wood contends, ‘the usual distinction between “being” and “acting” is totally collapsed’ (1998: 321). In addition, references to Georges Bataille, whose extravagantly pornographic Story of the Eye (1928) is Céline’s reading matter on the train, Sandro Botticelli, James Joyce, Georges-Pierre Seurat, Thomas Mann, W. H. Auden, Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas with its evocation of ‘past attitudes to romantic love’ (Wood 1998: 321), Yo-Yo Ma playing Bach and an unseen harpsichordist playing the Goldberg Variations (a particularly resonant example of a dialogic work in which harmony, melody, rhythm and orchestration is purposefully altered) all originated in workshopped rehearsals that carried on throughout the shooting of a film that is not so much about love and death as it is a dialogue between them. In this respect, the film’s key line of dialogue is Céline’s admission of personal faith:

If there’s any kind of God, he wouldn’t be in any one of us, not you, not me, but just this space in between. If there’s some magic in this world, it must be in the attempt of understanding someone else, sharing something, even if it’s almost impossible to succeed. But who cares really, the answer must be in the attempt.

Her words are a dialogue not just with Jesse but also with Hermann Hesse, the German-Swiss novelist and poet whose work invokes an individual’s search for authenticity, awareness and spirituality, who wrote: ‘No matter how tight the ties that bind one human being to another, an abyss looms that love alone can bridge, but even then only narrowly and precariously’ (Hesse 2009). It is this sort of dialogue that illustrates the Bakhtinian strategy that prompts Speed to surmise that ‘intellect is positioned as a source of pleasure in

Before Sunrise’ (2007: 10). As Bakhtin argues: ‘The central and basic motif in the narrative of individual life-sequences becomes

love, that is, the

sublimated form of the sexual act and fertility [for which] language serves as the most readily available medium [of its expression]’ (2006a: 215; emphasis in original). According to Freud, sublimation is a psychological strategy that effects a defence mechanism, which suggests that Jesse and Céline’s dialogue is the refined expression of love. As motif, moreover, love opposes death, which means the only way to keep death at bay is to keep talking. As for

Slacker and

Waking Life, therefore, all the walking and talking of

Before Sunrise asserts the importance of the individual (and the couple) within a society debased by the commodification of love in the consumerist hard sell of ‘aesthetic values made possible by Postmodernism’ (Geuens 2000: 3). Dialogue, like the sex it sublimates, is an intuitive response to death and dying. As Henri Bergson wryly states, ‘the ancient philosopher who demonstrated the possibility of movement by walking was right: his only mistake was to make the gesture without adding a commentary’ (1992e: 144).

Walking and talking is not just proof of life but its defiant declaration. This is obvious in the way that death utterly dominates the dialogue between Jesse and Céline and in the way they keep walking and talking in an effort to deny death its dominion. Jesse recounts stories of when ‘my mother first told me about death’ and he saw an image of his dead great-grandmother in the spray from a hose, while Céline is ‘afraid of death twenty-four hours a day’ and leads him to the Friedhof der Namelossen (the Cemetery of the Nameless) where ‘almost everyone buried here washed up on the bank where the Danube curves away’. Jesse has an elaborate theory about reincarnation that means ‘at best, we’re just these tiny fractions of people’ and Céline professes to ‘this strange feeling that I’m this very old woman, lying down about to die, you know that my life is just her memories or something’. When she was younger, Céline used to think ‘that if none of your family or friends knew you were dead, then it’s not like you were really dead’, while Jesse wants ‘to be a ghost, completely anonymous’, and for his fortune to be ‘when you die you will be forgotten’. For all its reputation as a romance, therefore,

Before Sunrise is almost unremittingly morbid.

6 All its walking and talking is but a negotiation of respite – ‘No delusions, no projections; we’ll just make tonight great’ – that is even more explicitly stated in the published script, when Jesse concludes their conversation on the boat with: ‘So it’s a deal? We die in the morning?’ (Linklater and Krizan 2005: 93). Continuing this theme, Céline even confesses to murderous fantasies about an ex-boyfriend and to being ‘obsessed that he’s going to die from an accident, maybe a thousand kilometres away, and I will be accused’, although Jesse, who Céline thinks ‘must be scared to death’ of her, actually believes that ‘women don’t mind killing men on some level’. Thoughts of death even permeate ideas of birth when Jesse recites the tale of a friend, who ‘at the birth of his child, all that he could think about was that he was looking at something that was gonna die someday’. Crucially, where sex might be expected to repulse the encroachment of death, it is dialogue that truly thwarts the reaper. Jesse struggles to admit this – ‘I don’t want to just get laid. I want to … um … I mean, I mean, I think we should, I mean we die in the morning, right?’ – and the consummation of the relationship is elided. The only thing that really opposes death is walking and talking: a drift and a dialogue that quietly rages against W. H. Auden’s thoughts, as quoted by Jesse, on how ‘vaguely life leaks away’.

7In comparison to the vitality of dialogue, moreover, love and sex is initially judged dormant as a defence mechanism because its complication by post-feminist attitudes is signalled as seemingly dead-ended.

Before Sunrise begins with a row between a married couple on the train and Céline’s opening line points to the curtailment of dialogue when she observes ‘as couples get older, they lose their ability to hear each other [.] I guess they sort of nullify each other or something.’ This premature disillusionment is echoed by Jesse, who admits that ‘my parents are just two people who didn’t like each other very much, who decided to get married and have a kid’, while Céline is upset that her grandmother ‘just confessed to me that she spent her life dreaming about another man’. Thus she believes that love is ‘a complex issue, you know. Yes, I have told somebody that I love them before and I have meant it. Was it a beautiful thing? Not really. It’s like … love.’ And Jesse is hardly more optimistic, saying he knows ‘happy couples, but it seems like they have to lie to each other’. However, such declarations are ironised because they actually emphasise how Jesse and Céline’s ability to maintain a dialogue is what keeps the demise of relationships and death itself at bay. Their dialogue may begin with the unpromising clichés of gender-speak in the scene on the tram when Jesse asks Céline to ‘describe your first sexual feelings towards a person’, and she in return asks him if he has ever been in love, but this awkward exchange is arguably the only moment in the film when audience identification with retrograde gender politics and stereotyping is allowed and quickly, quite rightly dismissed. Away from other people, the two of them share what a line in the published script describes as ‘a strange feeling. When we were talking on the train, it’s like we were in public. There were people around us. Now that we’re actually walking around Vienna, it’s like we’re all alone’ (Linklater and Krizan 2005: 28). Alone except for the camera, that is, which, unlike in

Slacker, refuses to break off from these people to follow others because, as soon becomes evident, the joy of dialogue rather than sex is what saves these two by elevating their

dérive through nighttime Vienna into a metaphysical experience: ‘It’s so weird, it’s like our time together is just ours. It’s our own creation. It must be like you’re in my dream and I’m in yours.’ Even though they recognise mortality again abruptly at dawn – ‘Oh shit, we’re back in real time’ – they are also gifted with the souvenir of knowing the transcendental quality of dialogue. As Jesse says of Céline: ‘She was literally this Botticelli angel, telling me that everything was going to be okay.’

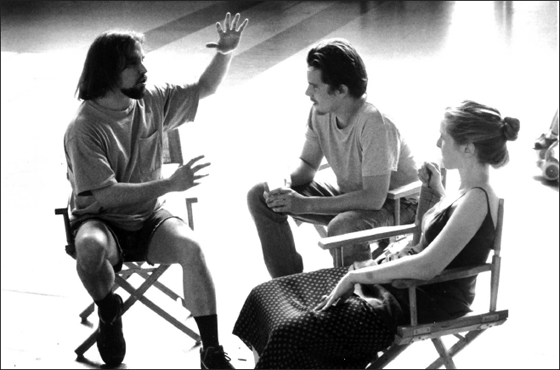

Richard Linklater filming Before Sunrise

All the singing and dancing of a musical usually culminates in a happy ending that sees the couple brought together and the community united around them. Here, however, the lovers part. Consequently, as Wood explains, ‘everyone […] raises the question of whether or not Jesse and Céline will keep their six-months-ahead date’ (1998: 322). The discussion is complicated by emotion, however, for Wood clearly subscribes to Bazin’s notion of appreciative criticism in admitting that Before Sunrise ‘was a film for which I felt not only interest or admiration but love’ (1998: 318). For Wood, Before Sunrise is ‘characterized by a complete openness within a closed and perfect classical form [in which] the relationship shifts and fluctuates, every viewing revealing new aspects, further nuances, like turning a kaleidoscope, so the meaning shifts and fluctuates also’ (1998: 324). Thus the dialogic work evolves through repeat viewings, special edition DVDs, intertextuality and influence, all the while trailing a cult following that extended the relevance of an emotional response to a dialogue about the fate of the characters that included Wood’s prescient idea of a one-sided reunion for which only Jesse turns up and Linklater’s possible response to this suggestion, for Wood suggests that his writing about this notion may have influenced Linklater, with whom he enjoyed a correspondence (1998: 324). More than this conjecture, however, just as the influence of Slacker is felt in such films as Baka no hakobune (No One’s Ark, Yamashita Nobuhiro, 2003), Die fetten Jahre sind vorbei (The Edukators, Hans Weingartner, 2004), 3-Iron (Ki-duk Kim, 2004), Azuloscurocasinegro (Dark Blue Almost Black, Daniel Sánchez Arévalo, 2006), and Slackistan (Hammad Khan, 2009), so the cost-effective simplicity of ‘boy meets girl, they walk and talk’ became a template and reference point for independent filmmakers who saw the intimacy and dialogue of their protagonists as a way of achieving the same with their audiences. Once (John Carney, 2006) actually is a neo-realist musical, while Quiet City (Aaron Katz, 2007) matched co-writer Erin Fisher as Atlantan Jamie to Brooklynite Charlie (Chris Lankenau) for twenty-four hours of coleslaw, galleries, after-party musing and a directionless race in the park between soulmate slackers who have no idea how fast they can run. In Search of a Midnight Kiss was another no-budget variation on the theme that paired gloomy Wilson (Scott McNairy) with pragmatic Vivian (Sara Simmonds) in Los Angeles and met with critical success that rarely failed to mention the influence of Before Sunrise or note that both films shared a producer (Anne Walker McBay) and that Holdridge thanks Linklater in the credits (Ebert 2008; French 2009). Yet another was Monsters (Gareth Edwards, 2010), commonly described as Before Sunrise meets Godzilla.

The generic lineage that connects classic melodrama with the more contemporary romantic comedy also exemplifies the dialogism that is explicitly retained in

2 Days in Paris (2007), which was written and directed by Delpy. Here, Marion (Delpy) and Jack (Adam Goldberg, who played Mike in

Dazed and Confused, One of Four Men in

Waking Life, an uncredited man asleep on the train in

Before Sunrise and was Delpy’s real-life partner for several years) bond and bicker in comedic but barbed illustration of how, as Marion moans, ‘there’s a moment in life where you can’t recover any more from another break-up’. In a similar vein,

Lost in Translation (Sofia Coppola, 2003) finds palliative philosophy in the platonic May–September romance of Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson) and Bob (Bill Murray). More recently still,

Last Chance Harvey (Joel Hopkins, 2008) employs the template for an October–September affair between Harvey (Dustin Hoffman) and Kate (Emma Thompson), while

(500) Days of Summer (Marc Webb, 2009) finds extra mileage and a twist revealed in its tagline: ‘Boy meets girl. Boy falls in love. Girl doesn’t.’ The dialogic work is clearly one that empowers the filmmaker (as it would an artist or writer) to ward off irrelevancy and stagnation. In contrast, solipsistic and centripetal works such as Julio Medem’s

Caótica Ana (

Chaotic Ana, 2007) can temporarily scupper a career with their exclusive introspection, whereas the dialogic work is a centrifugal presence in art, culture and society that both sweeps up and throws off influences. In this respect the dialogism of

Before Sunrise is most evident in relation to its sequel

Before Sunset, which both revives the potential of Jesse and Céline’s love by re-infusing it with dialogue and revitalises the cinema of Linklater by the same means.

Reuniting in Paris in 2004, the time that has passed for Jesse and Céline in

Before Sunset is the same nine years for Linklater, his actors and the ideal audience that first saw

Before Sunrise in 1995. The morbidity that pervaded

Before Sunrise was a projection of fears around which was built philosophical conjecture, but the increased proximity of death in the sequel is more tangible and therefore conducive to a more practical and immediate response that is expressed in the urgency of the film’s 90-minute time-frame. In addition, the dialogue between the films is rendered explicitly in the questions that each asks of the other in their taglines.

Before Sunrise asks, ‘Can the greatest romance of your life last only one night?’ while

Before Sunset wonders, ‘What if you had a second chance with the one that got away?’ The use of the pronouns ‘your’ and ‘you’ also indicates a dialogue with the film’s ideal audience. In the first case, there is a clear suggestion that

Before Sunrise is about ‘you’ in the promise of identification with the protagonists, while the ‘your’ of

Before Sunset insists upon an evolution of this dialogue between the audience and the films to the extent that it has been personalised in the way that André Bazin intended and to which Robin Wood admitted. Linklater recognises the ‘omnipresent feeling of the audience, even when you’re writing. I don’t think you cannot consider that and work in this medium’ (in Hewitt 2004) and even admits to finding this dialogue at times invasive:

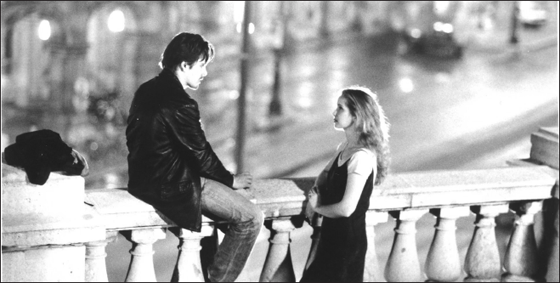

‘I don’t want to be one of those people that don’t believe in any kind of magic’. Jesse and Céline take the barge on the Seine in Before Sunset

Ethan, Julie and I talked and said, ‘No one wanted a sequel.’ There were three people in the universe who wanted a sequel, who wanted to get back into this, nobody wanted to do it. And now that we did it, and now we get asked if there’s going to be another, the idea that there’s an expectation now almost makes us feel like we do not want to make it. What was so cool was that every day on Before Sunset we looked at each other and it was like ‘How are we getting to do this?’ And it was like this gift from the film gods that we even got to make this movie, because there were zero expectations and zero pressure. It was just for us. But you do two and: ‘What’s next?’ People have expectations.

Long before talk of a second sequel, Linklater noted the growing fanbase for Before Sunrise and discussed the possibility of a first sequel with Delpy and Hawke in 2001 during the rehearsal for the brief oneiric reunion of Jesse and Céline in Waking Life. Yet it still took five more years for the project to evolve and the budget to be secured for a tiny fifteen day shoot. Firstly, Linklater and his actors agreed to co-write and met to work on a specific outline containing all the emotional beats. Then Hawke and Delpy invested in their characters by separating to work on their dialogue, which they emailed to Linklater, who collated contributions and re-wrote. Considerations of cost, schedule and filming restrictions made rehearsal and rigorous planning essential to the filming of Before Sunset. This time there would be no cutaways from the single conversation between Delpy and Hawke, whose greatest challenge (in addition to the rekindling of onscreen chemistry) was to appear spontaneous on top of so much rehearsal. ‘In the first film we were just getting to know each other,’ says Linklater:

But then that’s sort of why I cast both of them initially, because they seemed like the two most creative actors. Then, you know, cut to a couple of years later, they’ve both made a couple of features, they’re both writers. These people are really fucking talented and they really know what they’re doing and they’re really smart, visual artists.

At the same time, Linklater faced the challenge of maintaining a sense of spontaneity during a production that was inhibited by the practicalities of filming in Paris:

Paris was a tough city to film in. Vienna and other cities, they’re glad you’re there. Paris is the complete opposite. It doesn’t mean anything to them that you’re making a film in their city. In fact, if you need to come back tomorrow and finish a scene: ‘Go to the bureaucrat’s office and fill out the paperwork and maybe we can get you into that location next Thursday.’

Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke filming Before Sunset

Bureaucracy apart, Paris was also the home of the French New Wave. Linklater recalls ‘staying in the Latin Quarter and I would just walk to the set from my little apartment I was staying in and some of my favourite filmmakers have shot on these streets’. Inevitably, the influence of Truffaut, Godard, Rohmer and Agnés Varda, whose Cléo de 5 à 7 (Cleo from 5 to 7, 1962) has a similar time-frame, infused the tracking shots, sense of time, dialogue and urgency respectively, while all four informed the film’s empathy and melancholy about youth, particularly in relation to Céline, who prompts specific consideration of the effect and resonance of the events of 1968. In Before Sunrise Céline described her parents as ‘angry young May ‘68 people revolting against everything’, who had conformed to ‘this constant conversion of my fanciful ambitions into practical moneymaking schemes’. But in Before Sunset, the actual parents of Delpy, who was born in 1969, appear as jolly sybarites in the courtyard of her apartment block, thereby underlining this film’s theme of rejuvenation.

Initially, however, the lost potential of youth, the inexorable passage of time and the increased proximity of death are all themes that dominate the dialogue of Before Sunset and are expressed in the long takes that approximate time-images and the 80-minute running time that suggests the durée of the dérive. ‘It was such a huge challenge,’ recalls Linklater:

It was like a play. There was no room to cut out anything, so for Julie and Ethan it was tough. For most movies, if something doesn’t work, or doesn’t work as well as you’d like, you can always cut it, you can still work on the internal pacing with the editing; but that movie was totally designed one hundred per cent and then executed as designed. We made our choices and then lived with them. You’re painted into a corner, even geographically. We started here and ended here and the dialogue had to fit or we’d be timed out.

Consequently, dialogue is rendered as an even more urgent activity than it had been in Before Sunrise, because its existential nature is now expressed in the form and content of the ‘real-time’ conceit and its expression of ‘the volatile lightness of the dangerous present’ (Rosenbaum 2004). The guerrilla shoot may still have relied to some extent on improvisation, but, as Linklater explains, in a typically collaborative manner:

That’s the dynamic between Julie, Ethan and myself, we’re all just brutally honest with ourselves and with each other. There’s no bullshit. We have a great time collaborating on these movies and it’s all pure honesty and it’s the best kind of collaboration. If two of us feel strongly about something and something’s working for us and the third party doesn’t quite get it, it goes away. So everything in that movie was signed off by all of us. There’s never a point where I have to look at Julie and say, ‘I know you don’t like it but trust me on this.’ No, we’re all equally invested in everything. And that’s what just evolved in the second film particularly.

Nine years after the separation that concludes

Before Sunrise, Jesse is a debut author on a book tour of Europe to promote a novel titled