By definition no Cubist portrait can ever be complete because its subject exists in the time that it expresses and is therefore constantly changing, evolving, arriving and departing. So too is the cinema of Richard Linklater, whose movement between independent film and the studio system, between genres, European and American cinema, politics and philosophy is a product of versatility and variation. Linklater certainly disproves the assumption of idleness as a defining characteristic of the slacker ethos. Not counting all the work that he will go on to make, this portrait still lacks four vital fragments: a short documentary on the opportunity for creation and evolution provided by Ground Zero in post-9/11 New York that is Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor, a buoyant pilot for a sunken HBO series about minimum wage earners entitled $5.15/Hr, the extrapolation of a sports metaphor into philosophy that is the documentary Inning by Inning: A Portrait of a Coach, and the project being filmed a few scenes every year known as Boyhood. These fragments appear and disappear in the spaces between better-known projects, offering sketches, digressions and reaffirmations of themes and aesthetics. Although little known and in the case of Boyhood as yet unseen, they are all dialogic works that point to interwoven lines of political and philosophical enquiry and as such they illustrate and comment upon American society and its changing values.

For any American artist, writer, filmmaker or performer, the urge to commemorate the destruction of New York’s World Trade Center on 11 September 2001 was complicated by the crashing of this imperative into a taboo of unseemly enthusiasm. Nowhere was this concern about premature recovery or reflection more explicitly revealed than in the debate over what would become of the area where the twin towers had once stood. Suggestions were mostly dismissed as inappropriate because they either came unseemingly soon, were too opportunistic or too crass. Meanwhile, the area became both a place of pilgrimage for those seeking closure and a tourist attraction for those wishing to gawk at the rubble. The assimilation of 9/11 in the psyche of Americans in general and New Yorkers in particular was a painful process aided only by time and forgetting and perhaps the involuntary contextualisation of the event within the remembered grammar of disaster movies. But when speechlessness was cured, the event was incorporated into the history of the city and the intrahistory of its inhabitants. Iron girders fused in the shape of a cross were salvaged from the wreckage and erected on the site as a monument to the need for immediate memorialisation rather than to the event itself. A glimpse of the twin towers was edited out of the credit sequence for the HBO series

The Sopranos (1999–2007) and the trailer for

Spider-Man (Sam Raimi, 2002) and the airport signs pointing to Manhattan were doctored to cover the towers. The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) held an international competition to create a memorial that would ‘respect this place made sacred through tragic loss’ (Anon. 2009h) and tour guides revised their itinerary and commentary to both incorporate the event and participate in the reimagining of the area.

One such guide was Timothy ‘Speed’ Levitch, who worked on the Gray Line tour buses but had been in San Francisco at the time of the attack. Levitch was born into a middle-class Jewish family of five in Riverdale, the Bronx, in 1970. He attended Horace Mann, a respected co-ed private school but endured a painful adolescence as ‘a wallflower in the darkened corners of the cafeteria, acne-infested’ (Bruni 1998). However, his consequent introspection allowed him to embellish and philosophise upon his existence with such zealous eloquence that it earned him the nickname Speed. He studied creative writing at New York University, graduating in 1992, whereupon he took the examination to be a tour guide and started work with Big Apple Tours in a role that combined performance, language and philosophy:

I came to the tour route with the understanding that it is one of the great opportunities for self-expression and I do think that the people who really moved mountains in human history were all great tour guides. I do think that being a tour guide – understanding it to be a great opportunity for self-expression – enhanced my own use of language. It enhanced my understanding, if you will, that language is the instrument of life. It is the music of life and really a shamanic journey in its own right. (Levitch 2009)

He switched to Gray Line Tours in 1994 for a two dollar pay rise (making $9 an hour plus tips) and, as

The New York Times recounts, ‘around the same time, Bennett Miller, an aspiring filmmaker whose younger brother had gone to Horace Mann with Mr. Levitch, caught up with Mr. Levitch at a party’ (Bruni 1998). Miller proposed a documentary to be filmed during 1996 and 1997 that would observe and preserve Levitch’s Muppet-like performance of poetic improvisation, nasal eloquence and edgy, attitudinal quirks. Long before Linklater met Levitch, Miller’s

The Cruise (1998), which won the Don Quixote award at the 1999 Berlin International Film Festival, details Levitch’s fanciful guided tours or ‘loops’ around New York – ‘The sun, another great New York city landmark, above you on the left!’ – in the company of bemused, delighted and annoyed tourists for whom Levitch claims ‘each loop is a search for perfection’. This grainy black-and-white documentary takes in the sights from Levitch’s peculiar viewpoint while engaging with his resentment at having to observe his employer’s strict dress code and rigid timetable, and his vocational zeal at the possibility of ‘rewriting the souls’ of his passengers. Crucially for Levitch the world as it is represented in the microcosmic Manhattan exists exclusively in the present tense: ‘We are two blocks from where D. H. Lawrence lives! Two blocks from where Arthur Miller contemplates suicide!’ He justifies his state of eternal Bergsonian rapture by claiming that it is ‘in that active verb “fleeting” that I reside in the moment’. And in seeking erotic fusion with the time, place and space of his anthropomorphised metropolis he literally embraces the Brooklyn Bridge, claiming the city as ‘a scintillating, streamlined mermaid who sings to me at night’. For Levitch, New York City is ‘a living organism [with which] my relationship is in constant fluctuation’. Consequently, he berates the business and busy-ness of the city dwellers, describing commuters arriving at the World Trade Center as ‘running towards their destinations and from themselves’ and claiming that only the joggers and cyclists found ‘lounging or kissing in the park are historically accurate’. Most determinedly for Levitch, the ‘vocational double-decker tour’ itself is a motorised

dérive or drift (aka cruise) through the urban jungle for which chance and improvisation is essential to the success of its application of psychogeography. Thus he rails against the ‘anti-cruise’ of the grid plan of the metropolis and informs his tour group that their driver ‘Martínez continues to audaciously improvise, not only with the tour route but with his own life’. A traffic jam, for example, is not a headache but an opportunity for all on board to ‘sense the grandeur of [their] power’ as their bus causes chaos and gridlock.

Levitch’s conviction that time and all its subjects exist in a Bergsonian eternal present tense, his enthusiasm for the psycho-geographical experience of the dérive as propagated by Guy Debord, the Situationist International and the protagonists of Slacker, and his depiction of New York as ‘a self-orchestrated purgatory’ as well as his innate, extant romanticism (‘We are wreckage with beating hearts!’) is what impressed Linklater when he first saw The Cruise in which Levitch pointedly exclaims that ‘one of the great tragedies of civilisation is that people have to work for a living’. Linklater met Levitch in 1998 after a screening of The Cruise and was impressed by his physical and verbal combination and expression of the infantile and the cerebral that is a common contradiction of so many of the protagonists of the films he has written, co-written and directed. In his unkempt adenoidal exuberance Levitch is a mix of jester and prophet, benign but boasting of self-aggrandising martyrdom:

Creativity I think of as the pursuit for the original exuberance that we all came into this world with – the exuberance that we all had until it was taken off to an abandoned dock somewhere and shot in a gangster assassination by the outside world. With that said, I’ve always thought of myself as a renaissance man and I’m pouncing with avarice on all opportunities and doing my best to experience complete self-expression and pursue the fullest applications of self. Yeah! (Levitch 2009)

‘Where others see fragments, Speed sees connections’, says Linklater (2003), who would re-team with Levitch in 2012 to create an episodic travelogue for subscription website Hulu titled

Up To Speed. Levitch’s undeniable erudition and the results of his reflection can be both intoxicating in their realignment of priorities and overpowering in their verbose extemporisation. For example, in

The Cruise he gushes:

I think, most notably, that our true state is the greatest party that has ever been thrown. On the cruise, we define life as an ongoing opportunity for celebration. I would say that it is an unintentional meditation and an elongated journey into our own forest. I think life is a gigantic adventure that leads back to ourselves. I think that meaning is just a subsequent invention, if you will, a rivulet off the original river that is our learning process. It seems to me at this point in my life that we are all involved in a process and that process is about learning. I think the earth in the long run is a giant classroom. Is that what you were asking? I could go on a long time.

The appropriateness of Levitch to Waking Life was such that Linklater obliged Main Character to take the astral plane out of Austin to Manhattan purely to meet Levitch as ‘Himself’ on the Brooklyn Bridge. With hair like a roman candle and eyes like Catherine wheels, the rotoscoped Levitch in Waking Life informs Main Character that ‘on really romantic evenings of self, I go salsa dancing with my confusion’. He then prefigures the Bergsonian conclusion to the film offered by Linklater as Pinball Playing Man that ‘there’s only one instant, and it’s right now, and it’s eternity’ with his declaration that ‘the ongoing wow is happening right now’. Life itself, he proclaims, ‘is a matter of a miracle that is collected over time by moments flabbergasted to be in each other’s presence’. As both clown and commentator, Levitch comes at us live, direct from Bakhtin’s carnival.

Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor is a response to Levitch’s premonition of 9/11 in Miller’s

The Cruise, when he had spun like a child between the twin tower monuments to crammed-in Capitalism in order to summon up the dizzy feeling when ‘it looks like the buildings are falling on top of you’ and concluded: ‘This is ludicrousness and it cannot last.’ However, the destruction of the World Trade Center on 11 September 2001 meant that New York City no longer existed in the present. Instead, so defined was the metropolis by the absence of the World Trade Center that the only valid frame of reference for the reality-shattering event was the contrast with its presence in the past. Commentators were plentiful but mostly cautious and the majority looked to historical causes and global consequences. In

9–11 (2001) Noam Chomsky argued, ‘nothing can justify crimes such as those of September 11, but we can think of the United States as an “innocent victim” only if we adopt the convenient path of ignoring the record of its actions, which are, after all, hardly a secret’ (2001: 35). Meanwhile, Susan Sontag weighed in with an article in

The New Yorker that argued, ‘a lot of thinking needs to be done [but] the public is not being asked to bear much of the burden of reality’ (2001). Linking these two truths was a groundswell of feeling that all those affected by the event should accept some measure of personal responsibility for both its occurrence and its cure. Never mind that Jean Baudrillard had declared this was ‘the absolute event, the “mother” of events, the pure event which is the essence of all the events that never happened’ (2009). Gradually a feeling grew amongst some New Yorkers that the overwhelming magnitude of what had happened was no excuse for evading personal obligation to comment, communicate and contribute to this opportunity to reform relationships, priorities and policies. The problem was that Ground Zero spoke only of what was gone, thereby locking New York forever into the past. Correlatively, the Levitch who appeared in

The Cruise no longer celebrated the eternal present because Miller’s imagery and Levitch’s rhetoric was now impossibly frozen in a pre-9/11 past whose very completion signalled an end to Bergsonian time and the curtailment of the present tense. As Baudrillard stated, ‘by collapsing (themselves), by suiciding, the towers had entered the game to complete the event’ (ibid.). The problem thereafter was that the whole world would similarly regress; it would stop living in ‘the ongoing wow’ and reside forever after in the moments pending what Baudrillard called ‘the brutal irruption of death in direct, in real time, but also the irruption of a more-than-real death: symbolic and sacrificial death – the absolute, no appeal event’ (ibid.). For Levitch and Linklater this was never more explicitly problematised than in the competition administered by the LDMC to select a design for a memorial ‘that would remember and honor all of those killed in the attacks of September 11 2001 and February 26 1993’ (Anon. 2009h). From the 5,201 submissions it received, the LMDC selected ‘Reflecting Absence’ by architects Michael Arad and Peter Walker, which would ‘consist of two massive pools set within the footprints of the Twin Towers with the largest manmade waterfalls in the country cascading down their sides’ (ibid.). The structure would be engraved with the names of the dead in order to serve as ‘a powerful reminder of the Twin Towers and of the unprecedented loss of life from an attack on our soil’ (ibid.). But when Levitch and Linklater visited Ground Zero together in late 2001, they, along with many other artists, demurred.

As Linklater recalls, ‘while respectful of the tragedy, [Levitch] was his usual optimistic, present-tense self’ (2003). Instead of a redundant monument to the receding past they imagined a ‘delightful, benevolent opportunity’ (ibid.) to install a living thing that would speak of ongoing change. They rejected the notion of a monument to loss which would also serve as a mnemonic for revenge. Instead, they attempted to transcend the supposed sacrilege of simply appreciating the new skyline and its freshly unencumbered view. ‘The World Trade Center towers did not die, they created more space,’ says Levitch in Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor. His idea was to rescue New York City from the past and return it to the eternal present. ‘The gap between the twin towers represents non-communication,’ he declares with a jarring but curative use of the present tense, whereas ‘every citizen of every city I’ve ever met certainly deserves a hug’. Instead of attempting to embody meaning in a new construction based on the clichés of waterfalls, pools and the engraved names of the deceased, Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor proposes: ‘Sixteen acres of blazing green grass, a place for togetherness, healing out loud, and spontaneous culture. And in the middle of the park, the memorial should not be an inanimate slab of stone, but should have a heartbeat.’ In fact, as Levitch expounds, this heartbeat could be both literal and multiple:

It’s called ‘The Buffalo Idea’. It’s an idea that came about from a whole conversation of artists. And we’d like to use the land currently called Ground Zero and turn it into a Joy Park and grazing land for American Bison. The idea is that the central monument should not be an inanimate piece of stone but it should be something that’s alive, that has a heartbeat and that propagates. I think that a lot of what was felt by the people who came up with the idea is that the American Bison represents an indigenous American community that has been experiencing September 11th for 400 years. (In Dashevsky 2003).

Although ‘The Buffalo Idea’ would never be realised, Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor is its impassioned pitch. Shooting guerrilla-style on just one day (23 June 2002) emphasised the rescuing of the present tense, which was also underlined by the film’s opposing the gritty monochrome of The Cruise with its vibrant colour. The hand-held camerawork and jump cuts also evoke a palliative immediacy while its subjectivity puts the spectator in the position of Main Character in Waking Life, whose fleeting pilgrimage to Levitch is enacted in the dreamstate that Levitch now prompts us to recover: ‘I don’t like New York City but it’s my favourite place to get lost in. Now take out “New York City” and put “consciousness” in.’ Once again, the recourse to metaphysics prescribed by Linklater and Levitch is anchored to a paradoxically profound sense of place: ‘To be lost in New York City is to actually be quite precise about your place in the universe,’ says Levitch, who Linklater presents by way of jump cuts that aid disorientation while also framing the experience exclusively on this prophet in order to emphasise just how personal is the tragedy of the city. This profound personalisation of the event is also what deflects any potential outcry at their radical alternativism. America, says Levitch to camera, is ‘a land that is terrible at commemoration’; which is why Linklater reasoned that ‘an entirely new way of looking at the issue was what was needed. What the hell – so many of the things we take for granted and enjoy as part of our lives were initially crackpot ideas the establishment scoffed at’ (2003). No stock footage of the attack is included, diluted and perverted as it is by memories of disaster movies and looped newsreel. Instead, at a chatty 21 minutes, Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor seeks to affectionately persuade its audience of its strategy for a ‘joy park that is our strategy for survival’. Ground Zero, it is argued, is where destruction meets creation: behold the cosmic big bang coming to you LIVE! from Shiva’s dance floor in which the libidinous Levitch aims to involve us. This is ‘counter-intuitive. It has nothing to do with rationality,’ admits Levitch, who claims the idea of relocating roaming buffalo offers ‘a complete illustration of subconscious expectations for the future’. Consequently, even if it never actually happened, there was some triumph in just having people imagine it.

Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor received its premiere in January 2003 at the Sundance Film Festival, one week after the public hearings on the new site proposals for the World Trade Center that were met by The New York Times with the headline ‘New Trade Center Plans Draw Some Old Complaints’:

Since the attack on the World Trade Center 16 months ago, the public has responded to calls for comment on rebuilding the World Trade Center with a host of new ideas, innovative thinking and considered debate. Last night, however, when officials tried to engage a citywide audience in a discussion about a new set of designs for the trade center, the public appetite for it seemed to hit a dead end. (Wyatt 2003).

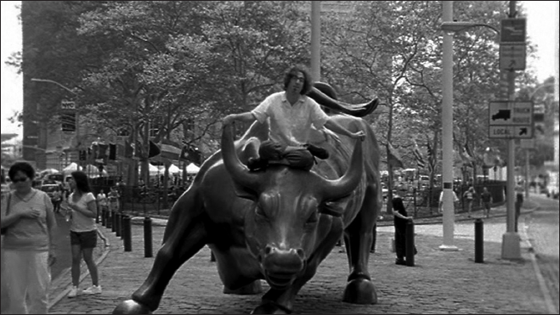

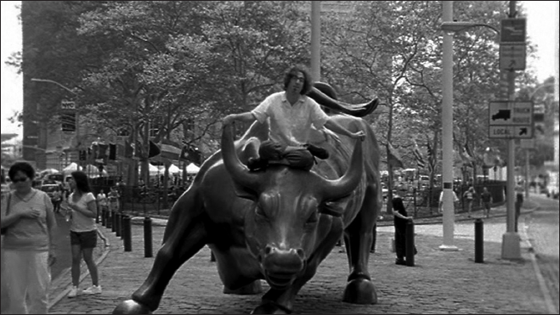

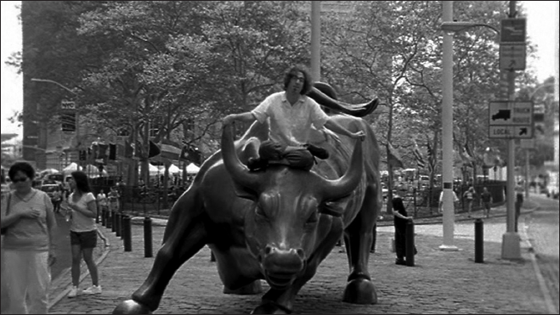

Public apathy stemmed from disillusionment with bureaucracy, stated the New York Times, which reported calls from the audience for the LMDC to ‘pay more attention to the needs of low income people on the Lower East Side’ (ibid.). But the city’s government was clearly regressing to ignorant, irrelevant, inconsequential ideas of monuments to capitalist excess. Aiming to break this interdependency with Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor, Linklater allows Levitch to preach from on top of the eleven feet tall, 3,200 kilogram bronze sculpture called Charging Bull (1989) by Arturo Di Modica that stands in Bowling Green near Wall Street. This act not only shows Levitch taming Capitalism (a bull market is a strong stock market) but fulfils the title of the film, for a bull was the mount of Shiva, the Supreme God in the Shaiva tradition of Hinduism. Moreover, Shiva (like Levitch) is noted for his matted hair and most often represented either meditating or dancing the vigorous Tandava that sets in motion the cycle of death and rebirth that Levitch evokes explicitly in locating Ground Zero at ‘the corner of creation and destruction’. Perched cross-legged atop the public statue, he appears to disprove the either/or of Monty Python’s Life of Brian (Terry Jones, 1979) in being both messiah and a very naughty boy.

In the associations that make up Levitch’s stream of consciousness, it is fitting that he should claim the symbolism of this bull for Shiva, thus elevating the film’s concerns, as he states, ‘beyond the duality of the bull and bear market’. He was certainly not alone in finding distasteful the erection of a monument that might be read as the rebuilding of Capitalism. And, although the debate he engenders cannot extricate itself from the mournful hush that dominates discussion over ‘moving on’ from 9/11,

Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor does make a brave stab at reclaiming the public space of Ground Zero in an oppositional monologue that renders Levitch every bit as defiantly optimistic a performer as Gene Kelly ‘laughing at clouds’ in

Singin’ in the Rain (Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly, 1952). Indeed, there is great musicality in his speech, which Linklater allows to develop in long takes. Ground Zero is thus reclaimed for carnival with Levitch as Bakhtin’s jester. Although some may find his ideas (and appearance) grotesque,

Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor presents him as a leader of the dance and Linklater is ‘excited to be part of it – anything that might help put Speed’s ideas further out into the public discussion could only be a positive thing’ (2003). Their joint aim is to inspire the public to join in the

dérive that leads to the dance and thereby recognise the potential for reterritorialisation and communication, although, as Koresky observes, ‘Linklater’s cinematic gesture is warm and undidactic, unable to provide answers to tragedy, he simply holds your hand’ (2004a). Levitch and Linklater want people to reclaim the streets for human connection (as folk do in

Slacker, Dazed and Confused, Before Sunrise, SubUrbia and

Waking Life) and in this at least they were in tune with public opinion, for, as

The New York Times reported:

Timothy ‘Speed’ Levitch atop Charging Bull in Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor

The Civic Alliance to Rebuild Downtown New York, a consortium of planning and civic groups, also played host to a multiday workshop last month to consider plans and ideas for downtown. A strong element that emerged from that effort was a desire for reinvigorated street life. (Wyatt 2003)

The task of identifying clear political affiliation in the cinema of Linklater is always problematised by the characteristic blending of any political sense into a philosophical sensibility. In

Slacker, Waking Life, Before Sunrise, Before Sunset and

A Scanner Darkly it might be argued that the protagonists use philosophy as a shield and, therefore, that in

Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor Linklater employs an actual philosopher like Levitch as a shield-bearer. However, it is also apparent that although Linklater speaks on camera himself in

Slacker and

Waking Life, his perspective as director is arguably expressed in the films’ aesthetics. Here, in appropriating the Dogme-style criteria for realism (handheld camera, colour film, diegetic sound, and so on), he subscribes to immediacy as a revolutionary act that opposes media manipulation and the crawl towards consensus of committees that is so often overruled by the ultimate dogmatism of accountants. Recognising that the attack on the World Trade Center had expressed this very immediacy in the impact of what Baudrillard called its unrepeatable, real-time, pure event, Linklater responds by twinning the destruction of the towers with the instantaneous aesthetics and production process of this film. Levitch is an improvisational collaborator, but also a clown handed a pulpit by his director. However, this is not to say that their working relationship is imbalanced, for each relies on the talents of the other, with Linklater providing the ideal platform on which the hyper-kinetic Levitch happily performs. Nonetheless, if one demands a more explicit statement of political commitment in the cinema of Linklater than that which can be deciphered from its plentiful philosophical discussion, its valuing of metaphysical experience and expression, its protagonism by dedicated slackers, its affined aesthetics of immediacy and its

durée, and the association of so much of its form and content with the purpose of the

dérive and the meaning of carnival, then one may encounter frustration. Asked straight out whether he considers himself a political filmmaker, Linklater himself colludes in this theory:

Not on the sleeve. But everything’s politics. The politics of everyday life is in all my films. I wade into politics in art really carefully, but I admit there’s a rebellious, subversive streak in everything I do. It’s never from the overclass perspective or of the status quo. If I had to do that it would be like a Buñuel film.

1

As has previously been noted, many of the films he has directed bear affiliation with those of Luis Buñuel, who summarised his own career in film when he wrote that:

The thought that continues guiding me today is the same that guided me at the age of twenty-five. It is an idea of Engels. The artist describes authentic social relations with the object of destroying the conventional ideals of the bourgeois world and compelling the public to doubt the perennial existence of the established order. That is the meaning of all my films: to say time and time again, in case someone forgets or believes otherwise, that we do not live in the best of all possible worlds. I don’t know what more I can do. (1985: 107)

As Linklater admits when pressed to consider his films from a Buñuelian perspective, ‘many of these are perverse subjects, when you talk about social strata and expectations.’ Thus, as previously indicated, Slacker is his La Voie lactée, Dazed and Confused is his Los Olvidados, SubUrbia is his El ángel exterminador and Waking Life is his Le charme discret de la bourgeoisie. Even Before Sunrise and Before Sunset have something of Cet obscur objet du désir (That Obscure Object of Desire, 1977) about them in their emphasis on love as an irresistible force and their discussions of that which Peter William Evans describes in relation to Buñuel’s final films as ‘a prevalent aura of anguish, the reflection in the microcosm of the wider inquiétude that governs the world’ (2007: 47; emphasis in original). Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor is therefore Linklater’s Simón del desierto (Simon of the Desert, 1965), for Levitch is a prophet adrift in Manhattan, just like the fourth-century saint who sits alone on a pillar in the desert in Buñuel’s short masterpiece, until the devil tempts him down with entry to a bohemian party in 1960s’ New York.

Unlike Buñuel, however, Linklater subscribes to metaphysical creation rather than Surrealist destruction. In films such as

Viridiana (1961) and

Tristana (1970), Buñuel rendered beggars and cripples as a gallery of grotesques whose base instincts made a mockery of Christian charity (which was admittedly Buñuel’s target, for these films were aimed at Spain’s Church-backed dictatorship of Franco). But the protagonists of the cinema of Linklater are often on minimum wage by choice and their slacker lifestyle is redolent of a kind of low-key heroism for their oppositional retention of youthful idealism, non-conformist attitudes and cynicism. Where Buñuel aims ‘to explode the social order’ (1985: 107), these characters seek to transcend it. If there is a common theme in the cinema of Linklater it is the awakening consciousness of un-moneyed drifters on their

dérives, starting with the director himself in

It’s Impossible To Learn To Plow By Reading Books and including all those in

Slacker and

Waking Life, on through

The Newton Boys and Mitch in

Dazed and Confused, Jeff in

SubUrbia, Jesse and Céline, Dewey Finn in

The School of Rock, Morris Buttermaker in

Bad News Bears, Amber in

Fast Food Nation and Levitch in

Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor. Even Richard in

Me and Orson Welles works for nothing but the privilege of being in the company of Orson Welles in the ‘rebuilt’ New York of the film’s authentically detailed 1937. Moreover, in relation to the rebuilding of New York and the awakening consciousness of its inhabitants, it is worth considering how it was that only 2,801 people died in the attack on the twin towers, when ‘some 50,000 people worked in the World Trade Center [and] another 150,000 to 200,000 business and leisure visitors came to the center daily’ (Anon. 2009i). This may partly be explained by the fact that the first plane hit at 8.46 in the morning, which meant that not too many business people had arrived for the beginning of the working day. But this also suggests that many of those killed would have been cleaners, technical staff, support staff and the like: low-wage workers finishing up the night shift or starting the early morning shift before the main workforce arrived. Thus, as

Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor argues, it is quite wrong that the concrete monument to world trade should be rebuilt because those who died were arguably victims of Capitalism too.

Levitch’s buffalo never made it to Lower Manhattan, of course, while another failed attempt at pitching a monument to those on minimum wage was $5.15/Hr. This is Linklater’s pilot episode for a series that was never picked up by the subscription cable television channel HBO, which had contributed greatly to a new golden age of writer-based quality drama on American television with shows like Six Feet Under (2001–5), The Sopranos and The Wire (2002–8). Set in Grammaw’s (Texan for Grandmother’s) diner in South Austin, the orphaned 25-minute pilot episode for $5.15/Hr is an affectionate but barbed portrayal of the workplace from the viewpoint of the powerless. Co-written by Linklater and Rodney Rothman, who had been head writer for The Late Show with David Letterman from 1996 to 2000 and supervising producer of Judd Apatow’s series Undeclared (2001–3), its unforced characterisation, narrative drift, particular sense of time and tetchy empathy amongst the co-workers is very much in the mould favoured by the cinema of Linklater, who admits, ‘$5.15/Hr was something I’d been trying to do for a while. It’s hard to do a pilot because you have to hint at what future episodes will be like. But that was something I really felt strongly about.’

Anyone who has ever had a job they hated will recognise the drudgery of dragging shifts offset by the in-jokes and hi-jinks that get one through the day of

$5.15/Hr. As Linklater points out, ‘there’s a long tradition of workplace comedies, particularly in the UK’ that American television has also maintained in shows like

Cheers (1982–93) and

Scrubs (2001–10), although the closest kin to

$5.15/Hr is early

Roseanne (1988–97) and the less zany moments of

My Name is Earl (2005–9) to which it matches its realistic view of America’s white working class and its affectionate look at their eccentricities.

2 That said, the tone of the pilot episode wobbles precariously between the observational, character-based humour in the diner and the absurdity of the scenes at the headquarters of the parent company Hoak Industries, where the tense banter between executives and the eccentric but dictatorial owner seems to have strayed in from a screwball farce. If it had been picked up by HBO, it is probable that the jarring ‘bookend’ scenes at Hoak would have been discarded much like the faux vox pops in the pilot episode of HBO’s

Sex and the City (1998–2004) or the blackly comic adverts in that of

Six Feet Under, although without them the ramshackle narrative of

$5.15/Hr lacks any conventional hook to bring the audience back for the next episode. In sum, one either likes hanging out with these ordinary folk or one does not, much like the HBO executive who cancelled the commission after viewing the pilot. As Linklater recounts:

They just thought it was depressing, this idea that people work so hard in a really shit job. They didn’t get it. But the people at the studio wouldn’t. They go from a rich upbringing to an Ivy League school and then into a position at a major corporation and work their way up from there. So a lot of people who are making these big decisions have no feel for working people. And I was like: ‘Hey! That’s my background!’ I threw it out there.

For Linklater, ‘throwing it out there’ meant regurgitating all that is distasteful about a fast food franchise and the conditions of the minimum wage earners it both feeds without nourishment and pays without perks. $5.15/Hr begins with a montage moving from the CEO of Hoak Industries to scientists testing flavours in a laboratory, industrial-sized pastry mixers and a conveyor belt of new apple desserts called fandangos that are frozen, boxed and delivered to Grammaw’s (‘Eat Till It Ouches You!’), whereupon the short order cook dumps them onto the counter and proclaims, ‘it looks like something that dropped out of someone’s ass’. Following this, the already weary staff congregate for the daily pep talk called by Mitch the manager (Mitch Baker), whose corporate-speak marks him out as both the inadequate alpha male and fall guy for all the resentment of his ‘human resources’. Bitter banter between short order cooks Vince (Clark Middleton) and sassy ‘soul sister’ Joy (Retta) adds an obscenity-laden corrective to Mitch’s slogan-filled rhetoric (the graveyard shift is now ‘the third shift’ and customers are to be referred to as ‘guests’), while Brianna (America Ferrara before stardom in the more up-market Ugly Betty [2006–10]) is a timid waitress whose habit of wishing customers God’s blessings leads to Mitch’s admonishment: ‘Not all of our customers are Christians, so from now on the only G word is Grammaw’s.’ Completing this collective is waitress Wing (Missy Yager), two Hispanic wage slaves who speak no English, and Bobby (William Lee Scott), who is late for the pep talk because he has fallen asleep on top of a (HBO-obligingly naked) bar-room pick-up: ‘Bobby, get up! You’re still in me.’ ‘I’m still hard.’ ‘I think that what’s called a piss-boner.’

$5.15/Hr is, like

Slacker, Dazed and Confused, SubUrbia and

Fast Food Nation, from the perspective of those who have realised they have few options but to work for minimum wage in convenience stores and fast food joints like Grammaw’s. Unlike Kevin Smith’s

Clerks, which was directly inspired by

Slacker, $5.15/Hr, which might be expected to share Smith’s youthful dislike of customers and duties, expresses a mostly flat acceptance that life is happening elsewhere. Obliged to beg for extra shifts, the wage slaves take their revenge by collective slacking. These are the people that time, President George W. Bush and all those ‘guests’ who never left a tip forgot.

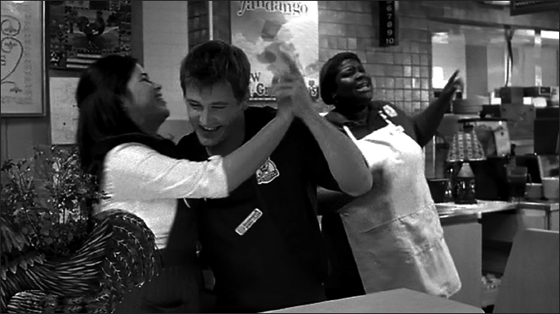

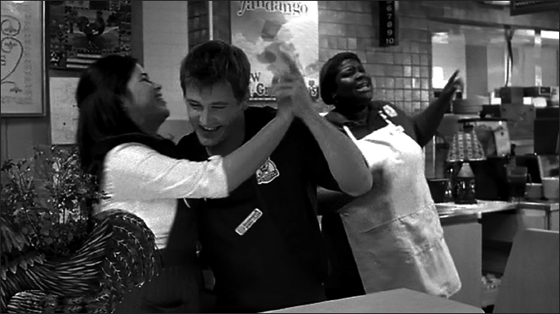

3 And, as the third (graveyard) shift drifts into the lull between late dinner and early breakfast, it is in the small hours that

$5.15/Hr makes its case for the collective when Joy puts some funky soul on the stereo and the staff spontaneously dance with each other amongst the empty booths. The touching gaiety of this sequence makes one regret that the true musical is one of the few genres not attempted in the cinema of Linklater, for, apart from the sports movie, this genre offers the most opportunities for celebrating the community. To borrow Peter Gibbons’ (Ron Livingston) classic line in the kindred Austinite slacker comedy

Office Space (Mike Judge, 1999), it’s not that these people are lazy, it’s just that they don’t care. However, as the graveyard shift proceeds like chronic jet lag, the waiting staff push fandangos on their diners, who can claim one free if they forget to do so and its cost comes out of their wages. Wing obeys but follows up her no-hearted sales push by telling customers: ‘It’s disgusting. It’s about a thousand calories and it’s probably been deep fried in a factory full of rat shit.’ But when drunken frat boys order them anyway, at least she gets to win ‘customer bingo’ by crossing ‘vomit’ off the grid full of already spotted ‘numbers’ such as ‘hand tattoo’, ‘leopard skin’ and ‘ugly guy with hot chick’.

$5.15/Hr is about doing what it takes to get through one’s shift without sacrificing one’s integrity, imagination or humour.

Brianna (America Ferrera), Bobby (William Lee Scott) and Joy (Retta) dance the night away in $5.15/Hr

Although too brief to even aspire to being episodic, this pilot still shows relationships deepening as the staff’s nocturnal dislocation effects a contrast with sleeping America. Bobby and Wing share a kid daughter whose maintenance is a matter for negotiation, while the pathologically cheerful Brianna endures harassment from lascivious male diners and initiates ‘positive action’ by pulling African-American diners from the queue first when Mitch points out she once left a couple waiting over a minute for a table at Grammaw’s, which is currently responding to a class action lawsuit on a racial matter. One significant advance on the smalltown Texan films in the cinema of Linklater is the acknowledgement of an explosion in their multi-culturalism since the period in which the almost all-white

Dazed and Confused was set and

Slacker was filmed. The 24/7 convenience stores are now all managed by Pakistanis, which was something new in

SubUrbia, and all have booths offering Cambio de Cheques (cash for cheques) at exorbitant commissions to Hispanics without social security numbers. Where

$5.15/Hr shows advancement is in its recognition of various strata of the Hispanic community in Austin and other towns that include the wage-earning but fearful Brianna, the bus-boy who gets fired for stealing tips and the anonymous illegals queuing to cash their cheques. This points to a new awareness of the complex social conditions of the Hispanic community in southern Texas. Consequently,

$5.15/Hr had specific consequences for the cinema of Linklater:

If HBO had followed through it would have been fun. Even if I hadn’t directed all the episodes of the series it would have been fun to see something live and breathe. But I experimented with it and I learnt a lot from it. A lot of the technical stuff and a lot of my feelings about that stuff ended up going into Fast Food Nation.

It was the experience of making $5.15/Hr that convinced Linklater that a fictional extrapolation was the most appropriate way of adapting Schlosser’s journalistic exposé Fast Food Nation, although persuading Hollywood to back such a project after the demise of $5.15/Hr was out of the question. Says Linklater: ‘Hollywood doesn’t want to finance stories about people at work, even if they’re comedic’ (Robey 2007: 24):

When you examine the fast-food industry, it’s a loser on every level: systematic cruelty to animals, environmental degradation, low-paid workers and a final product that’s horrible for the end user. You couldn’t design a more harmful, cruel situation. And yet it persists because everyone involved is answering to the bottom-line thinking that permeates our culture. (In Robey 2007: 26)

Nevertheless, Linklater persisted, finding funding for Fast Food Nation from the British Broadcasting Corporation’s film wing (BBC Films) as well as HanWay Films, led by Jeremy Thomas, and Participant Productions, which had produced mindful documentaries such as Murderball (Henry Alex Rubin and Dana Adam Shapiro, 2005), An Inconvenient Truth (Davis Guggenheim, 2006) and issue-based fictions such as North Country (Niki Caro, 2005), Good Night, and Good Luck (George Clooney, 2005) and Syriana (Stephen Gaghan, 2005). The line between documentary and fiction is often unclear anyway; for, as Douglas Morrey points out in consideration of Jean-Luc Godard’s dictum that all great fiction films tend towards documentary, just as all great documentaries tend towards fiction:

Even in the most artificially contrived film narrative, the

real world caught on film, will nevertheless make its presence felt; even the most rigorously factual documentary, by virtue of being organised through montage, partakes of fictional construction. (2005: 4; emphasis in original)

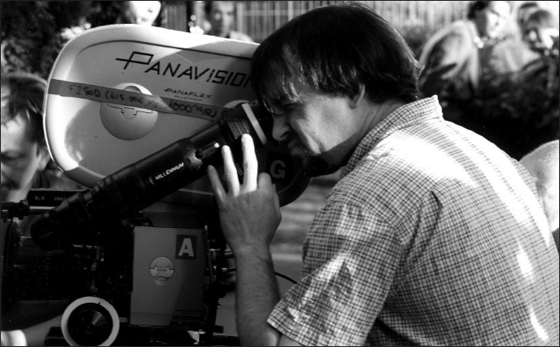

For Linklater this lesson would be learnt during the filming of the slaughterhouse scenes for Fast Food Nation – ‘I felt like a war correspondent who’d snatched a photograph of something horrific!’ – and corroborated by his subsequent production of a documentary on the University of Texas baseball coach Augie Garrido, Inning by Inning: A Portrait of a Coach.

Augie Garrido coaches National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division 1 college baseball and has more wins to his credit than any other coach in the league’s history.

4 Since 1997 he has coached the Longhorns of the University of Texas at Austin, which raised his salary to $800,000 per annum in 2008. Having gotten to university on a baseball scholarship and remained a lifelong fan of the game, Linklater has been known to participate in batting practice under Garrido’s tuition. The documentary that this friendship inspired is not really about baseball, however, but uses the sport as metaphor for a philosophy that Garrido expresses on the training ground.

Inning by Inning: A Portrait of a Coach is thus, like

Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor, a highly subjective documentary given to ‘fictional construction’ in which Linklater positions a gifted but workaday philosopher as spokesperson for the fusion of cerebral and practical expressions of slacking. In effect this continues Linklater’s characteristic presentation of the rhetoric of everyday philosophers such as Levitch, Garrido and Louis Mackey, who appears in the artificially contrived fictions of

Slacker and

Waking Life, just as the protagonists of the fictional films he has directed often express themselves through the philosophies and anecdotes of others. Jesse and Céline first get to know and then reconcile with each other by trading beliefs and values propagated or embodied by physical and literary acquaintances, for example, while Dewey Finn and most of the characters in

Dazed and Confused rely on attitudinal music to shape their thinking. Thus the catalogue of thinkers, writers and musicians that fictional characters posit as their spokespeople ultimately resembles the scramble suit of

A Scanner Darkly because it is constantly changing in its unending search for a connection with other people. However, in documentaries there is no fictional intermediary between the filmmaker and those who are quoted, there is only Linklater positing Levitch and Garrido as his spokesmen.

Inning by Inning: A Portrait of a Coach came about because Linklater ‘had gotten to know Augie [Garrido] over the years a little bit. As a former player, I just kind of liked his style. He has a kind of philosophical Zen attitude towards baseball’ (Moreno 2008). The affinity peaks with Garrido’s belief that players should focus on the moment at hand rather than the overall match or overriding objective of winning, thereby demanding investment in the Bergsonian notion of what Levitch calls the ongoing wow. ‘It’s what’s required in filmmaking for sure,’ says Linklater: ‘The end gratification is so deferred in a way. If you just want to make a good movie, if you don’t enjoy every step and become a master of each little moment, then you shouldn’t be doing it’ (ibid.).

Inning by Inning: A Portrait of a Coach took two years to complete, of which 18 months were spent editing the 600 hours of footage down to 106 minutes for its premiere at Austin’s Paramount Theater on 3 June 2008 to an audience of past and present University of Texas baseball greats, family, fans, and Garrido. It was sold for broadcasting to the American television cable Entertainment and Sports Programming Network (ESPN) and released in 2009 on a DVD that contained both broadcastcensored and unexpurgated versions of Garrido’s rousing, expletive-laden rhetoric. For the ESPN audience, the documentary fits snugly into the genre of hagiography as observational footage of Garrido pep-talking his players on the training ground alternates with televised footage of him shouting in the faces of umpires and rousing his team during games. All this is interspersed with talking head interviews with past and present players, childhood friends and family. Yet this is also a raw and simple portrait of a man who, like Levitch, lives his real life according to the philosophy that often guides fictional characters in the cinema of Linklater.

Garrido is the grandson of Spanish emigrants, whose father was a sharecropper in the Texas dust bowl and wanted his son to work on the shipyard. But at an early age Garrido saw a man performing with a yo-yo on the The Ed Sullivan Show, ‘getting paid and having fun doing it’, and was struck by the knowledge that his own skill with a yo-yo was much better. Thus he realised ‘that if you’re the best at what you do, you can make a living at it’ and he resolved to build a career ‘based on passion and the fact that I didn’t want to work’. Channelling this ambition into playing baseball, he became a coach when he ‘found out late that it wasn’t the game I loved, it was the people involved in the game and the relationships and the experiences’. His career as ‘the winningest coach in Division 1 NCAA history’ makes him a prized employee of the University of Texas, whose on-campus stadium dwarfs all its faculty buildings. Yet Garrido is not about winning; instead he sees baseball as ‘preparation for life, ethics, focus, ability, the courage to act on your thoughts’. In several scenes Linklater takes up a position with the camera in the huddle of capped and helmeted players to listen to Garrido’s paternal tirades: ‘Baseball is about coming to terms with failure without it becoming overwhelming. […] Do your best, you’re gonna fail. So you do your best again. […] This isn’t about some game, it’s about our lives!’

Garrido could very easily have strolled into Slacker or accosted Main Character in Waking Life, so redolent is he of the limited universe of the cinema of Linklater. His philosophy is centred on the collective, for which he insists that playing for fun is infinitely more important than competing for the prize. At heart, he espouses a simple formula: ‘Eliminate the fear – it’s fun!’ But he also makes sure his players understand their privilege in being able to reach for that ambition: ‘Let me put it this way. How many guys your age in Iraq have died? Now ask yourself if you’re doing your best.’ When asked if Garrido’s overriding philosophy of ‘you can be as good as you can be’ is also his own, Linklater replies: ‘Yes it is. He’s a friend of mine but in some ways it’s a self-portrait of a process.’ This process is one of self-fulfilment and creativity through the challenge of preparation at a sensible remove from injurious competition, for it is preparation, teamwork and positive thinking that give rise to the possibility of inspirational performance during a match. As such, Garrido’s approach to baseball serves Linklater as a metaphor for a philosophy of filmmaking:

I saw a complete analogy with filmmaking, with the team just preparing for the game. Filming is not as important as pre-production but it’s never totally worked out. It’s like for an athlete. All that stuff is practice, but the shooting is the final game where you maybe discover something extra. You may wake up the morning of the game with the final good thought. That’s why I always pace it so you’re absolutely peaking when you’re shooting that scene. Otherwise you’re driving home at the end of the day having new thoughts that would have made the scene better. But it’s too late then. I never do that. I’ve always thought it to death first and peaked in the game. You work out everything you possibly can, but you peak in the game. You save it for the film.

As Garrido maintains that pacing and preparation is crucial to life, so Linklater transposes this philosophy to the project known as Boyhood, filmed in short sequences over the space of twelve years in order to map out the stages in a boy’s adolescence. In adding fragments to a Cubist portrait of the cinema of Linklater, Boyhood appears as a meta-portrait for its own fragmentation of a fictional life that reflects contemporary America too:

It’s about a boy. It’s contemporary, very contemporary. What I’m shooting is what’s happening. It starts when he’s about six or seven, just getting out of first grade. It’s kinda like the public school here goes first to twelfth grade, so it’s twelve years. This year he’ll be in seventh grade. So it’s in and around school but it’s not always in school. And right now [2009] he’s turning thirteen. I’m halfway through. I shot my sixth episode last fall. I’m gearing up to shoot another one.

The protagonist of the film is Mason (Ellar Salmon, who played Jay Anderson in

Fast Food Nation), whose divorced parents are played by Ethan Hawke and Patricia Arquette. ‘They’re around about every other episode,’ explains Linklater: ‘Last year Ethan had a camping trip with his son and Patricia wasn’t in it.’ However, the subject of the film is time and cinema or as Linklater puts it: ‘Pure cinema, where the lead character is really time.’ To this end, every year Linklater stages both a ‘family’ reunion and one with a tiny but committed crew. Shooting in a documentary style, Linklater recognises the influence of Michael Apted’s

Up series of films charting the lives of fourteen children since 1964 with seven year ellipses that also resonates within the relationship of

Before Midnight to its prequels and the series of films featuring Antoine (Jean-Pierre Leaud) directed by Truffaut. This is because the sense of pure cinema he purports to seek in recording the actual growth of a boy similarly blurs the distinction between character and actor that underpins the portrayals of Jesse and Céline; although here, for all the potential cruelty of adolescent growth spurts and hormonal highs, the changes to Mason/Ellar Salmon will be so gradual as to resemble what might be Linklater’s holy grail of a

dérive (drift) through life. And not only for Salmon, as Hawke and Arquette will also expose their ageing in a film that Linklater believes will show them as crumbling portraits in the fashion of Dorian Gray: ‘The film is not in chapters, it’s segued,’ says Linklater: ‘That’s the interesting thing; it just follows. I’m shooting on 35 mm so I’m hoping it will all look the same. So you’ll sit and watch one movie and everyone just ages.’

Perhaps the biggest obstacle to a project such as this is securing the long-term commitment of the cast, which explains the collaboration of the dependable Hawke, who, Linklater recalls, ‘was on board easy because it sounded so crazy’:

Patricia I’d only met once. She was dating a friend of mine and I just called her up as I knew she had been a mother fairly young, about nineteen or twenty when she had a kid. And we talked for a couple of hours on the phone, and she just committed over the phone. You know, it was like: ‘What are you doing twelve years from now? I’m going to be trying to make a film and you’re going to be looking for a good part.’ This is what we do. It’s such a weird thing but this is what we do.

Other roles had to be filled with those who Linklater could rely on too: ‘My daughter plays his older sister, just because I knew where she would be. Because it’s hard to commit. You can’t contract anyone to do anything for twelve years. It’s against the law.’ How then does one limit the risk of losing Ellar Salmon, his star? ‘He could quit. He could move,’ accepts Linklater:

When you cast a little kid like that, you’re really casting the parents. And his mother’s a dancer. His dad’s a musician. They have deep Texan roots and Austin ties. And I kinda looked at it and figured, ‘Okay, I don’t know if their marriage will survive.’ And it didn’t. They got divorced somewhere in the middle of it. But that’s okay, that’s fine. It works for the story. I meet with him pretty regularly. He’s an interesting kid.

However, at a time when Linklater and most independent filmmakers are struggling to find funding and combine it with coherent distribution for even the smallest projects, perhaps what is most remarkable about Boyhood is that a production company has been willing to invest in a film that will show no possible dividend for at least fifteen years. That company is the Independent Film Channel (IFC), which co-produced Tape and Waking Life and has distributed the Saw horror film series (2004–) in the US. ‘I somehow talked them into this,’ says Linklater:

They’re so brave. They give me enough every year to shoot just that little, fifteen- or twenty-minute piece, which is long. I thought it would just be ten minutes every year, but I can’t help it. There’s just too much stuff. Last year was kind of short but this will be another big year. So at the end of the day it’ll be around three hours hopefully.

Adding to the realism of the project is its dismissal of any narrative beyond the combined ageing/filming process and the ongoing, semi-improvisational shaping of the events onscreen. Linklater insists ‘what they’re doing is pretty banal, you know? He’s in school and doing all the little petty things that you do growing up, but there’s some drama in the family, the mother gets remarried and they move around a lot.’ Moreover, Linklater professes to ‘kinda have an eye on what I think is going on to some degree. Last fall they were campaigning for Obama door to door, for example. You know, putting signs in yards, whatever’s going on.’ The notion that the film will have value as a time capsule and as a time machine, is also recognised by the filmmaker:

Like one year, when the Harry Potter books come out, there was this launch. My daughter and I have been to these things. It’s at midnight, people dress up in character and you go through the little railway station and there’s people handing out books. And I said, ‘next year we’re going to film this’, because it didn’t happen when I was a kid and it might not happen ever again that people are that excited about a book. So I had my characters waiting and worked that into thinking retrospectively from eight years into the future, thinking, ‘Yeah, that’ll seem weird.’

Editing, on the other hand, is an accumulative process subject to regular revision: ‘I edit every year and every two or three years I edit the whole thing again just to keep it all in mind. So I’ve got a pretty good cut of the first six years.’ And so the production continues, with Linklater expressing commitment to Coach Garrido’s dictum of thorough preparation for the game:

We get about three days of production per year, we don’t have much money, and we shoot about fifteen to twenty minutes. It’s pretty concentrated, the days are tough, but you have to prepare. There’s new casting, whatever. Most movies you prepare eight weeks and shoot ten weeks. This is like ‘prepare three weeks to shoot three days’, so at the end of the day you’ll have a year of preproduction and forty days of production. So it’s crazy. Every year it gets to be a lot more fun but it gets a lot more demanding too.

Proof, if any were needed, of the demanding nature of filmmaking is also evident in the many projects with which Linklater has been associated throughout his career without ever adding them to his CV. His independence and resolution to remain in Austin has often borne that downside of being adrift without backers or distribution for projects that a closer relationship with the major studios might have fostered, especially after proving his bankability with

The School of Rock. Yet he continues to nurture long-term projects such as

Boyhood and scripts that await technology or their right time: ‘I have a couple of films now that I’m into my second decade on, that I can’t even see doing in the next few years.’ Amongst these waylaid also-rans are a sequel to

The Last Detail (1973), which was directed by Hal Ashby and based on Robert Towne’s adaptation of Darryl Ponicsan’s 1971 novel about Seaman Larry Meadows (Randy Quaid) being reluctantly guided to prison by his military escort Billy Buddusky (Jack Nicholson).

Another casualty is

That’s What I’m Talking About, the ‘spiritual sequel’ to

Dazed and Confused that ran aground on a lack of distribution in 2009:

I spent seven or eight years outlining or plotting and then finally I get a strategy and a script and I go, ‘Okay, now I’m ready!’ It was a college comedy. I think it’s the funniest thing I’ve ever written. I really thought I had it financed, but we couldn’t really get a distributor. I couldn’t believe I couldn’t get distribution. It used to be if you had any money, if you had half your budget from equity or foreign sales… I got A Scanner Darkly made like that. And this was kinda shocking. So anyway, I’m in a holding pattern with that and a couple of other projects, scripts I’ve had for a while.

Working outside the major studios, Linklater admits that he has ‘always struggled with that anyway: to get certain films made.’ These include ‘a script about an auto assembly line worker in Flint, Michigan’ (Robey 2007: 24) and a black comedy called

Bernie that finally went into production in 2010.

Bernie recounts a true story from 1998 when the richest widow in the town of Carthage, Texas, Marjorie Nugent (Shirley MacLaine), was found in a large freezer in her home after being missing for nine months. Bernie Tiede (Jack Black), a popular and generous, assistant funeral director who had befriended Nugent when he supervised her husband’s funeral, admitted to killing her for her money but was supported by the townsfolk, who had neither cared for nor missed the snooty widow. In August 2010, an open casting call for

Bernie was posted on

www.shortfilmtexas.com asking for ‘Townspeople – Texans who are not necessarily professional actors … the real deal – funny and interesting folks. There are a lot of small parts in the movie, mostly for people over 40’ (Weidner 2010) and attracted online responses from many who had known the real Bernie.

Also on the ‘to do’ list is College Republicans starring Paul Dano as future Deputy Chief of Staff and senior advisor to George W. Bush Sr. Karl Rove., who worked on Richard Nixon’s 1972 presidential campaign and was nicknamed Bush’s Brain. The film, which will be partly produced by Maya Browne of Bratt Entertainment, explores the formative relationship between Rove and fellow student Lee Atwater, who would become Chairman of the Republican National Committee. In addition, there is the still unlikely sequel to The School of Rock as well as a biopic of Chet Baker co-written with Tape’s Stephen Belber and due to star Ethan Hawke. And there is also Liars (A–E), which was offered to Linklater by producer Scott Rudin but fell foul of Disney’s downsizing of Miramax in late 2009 after Rebecca Hall and Kat Dennings had been cast as friends on a road trip to Obama’s inauguration, collecting items left with ex-boyfriends on the way. At the time of this interview, nonetheless, Linklater was excited about the challenge:

It’s a change of gears for me: two women on a reflective road trip. I’ve got to do my

Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. Everyone has to do their purely female movie and I’ve always been amazed that I haven’t. You know,

Before Sunrise and

Before Sunset have a strong female character and sensibility, but I’d liked to have been a Fassbinder or a Bergman or someone; someone who makes more female movies.

Linklater retains the ambition to create a drama as complex and powerful as Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s television series Berlin Alexanderplatz (1980): ‘The cinema isn’t doing anything adult. I might have to get involved in television drama. Never say never. The right timing, the right subject matter…’

Periods of unemployment do not denote inactivity and are mostly subsumed within the fits and starts of any filmmaker’s career. Gaps also provide opportunities for other endeavours, such as Linklater’s involvement in lobbying for film incentives on behalf of the Austin Film Studios and working with MoveOn.org in 2004, which describes itself as ‘a service – a way for busy but concerned citizens to find their political voice in a system dominated by big money and big media’ (Anon. 2010b). Linklater made an advertisement for MoveOn prior to the 2004 presidential election aimed at encouraging voters to get involved in civic and political action. He also participated as judge alongside Susan Sarandon in the Fairview organisation’s Upgrade Democracy video contest, which invited amateur filmmakers to upload short films to YouTube that answered the question: ‘If you could change anything you wanted about elections, what would our democracy look like?’ And he judged the ‘Why We Don’t Vote’ essay-writing contest of the Center for Voting and Democracy and Midwest Democracy Center (Anon. 2010c). In addition to small parts and cameos in his own films that include him playing foosball in the music bar that Jesse and Céline enter in Before Sunrise and as the third member of the rock group in the photograph of Dewey and Ned (Mike White) in their younger days in The School of Rock, Linklater contributed the voice of a bus driver to Beavis and Butthead Do America (Mike Judge, 1996) and appeared as Ember Doorman in Underneath (Steven Soderbergh, 1995), Cool Spy in Spy Kids (Robert Rodríguez, 2001) and Principal Mallard in RSO (Registered Sex Offender) (Bob Byington, 2008). Finally, for insomniac completists only, there is Heads I Win/Tails You Lose (1991), a piece that Linklater compiled from the countdowns and tail ends of film reels that passed through his hands while curating the Austin Film Society between 1987 and 1990, thereby creating a cinematic monument to the excitement and frustration caused by films that are always arriving and forever departing. Thus, the climax of every film’s launch procedure is elided with the result that the spectator exists in a constantly aroused yet frustrated state of expectation that expresses Bergson and Linklater’s eternal moment as perpetual cinephiliac priapism.

And, having exhausted the CV, what is missing? In relation to what Corrigan calls the ‘commercial performance of the business of being an auteur’ (1991: 104), Linklater does not position himself as a celebrity or artist in comparison with various of his contemporaries but as a mostly non-Hollywood filmmaker who has been both liberated and limited by remaining in Austin all these years. To the extent that a commitment to recurring themes, a particular aesthetic and an insistent point of view is the basic criteria for an auteurist reading of any filmmaker’s work, one might at least identify all three in the disparate projects that he has directed, although the finished films differ greatly in genre, tone and style. Nevertheless, while mainstream cinema often exaggerates all it can, that of Linklater appears to embody the attitude of Uncle Pete in

Fast Food Nation of being quite all right with what it’s not doing. Whereas narrative convention exudes a compulsion towards resolution tantamount to a capitalist imperative to speculate greedily on the future, the cinema of Linklater most often digresses through dialogue that prompts characters such as Jesse and Céline to perceive and reflect upon the contrary experience of an eternal, incomplete present. Consequently, it is not the movement of any narrative-bound protagonist that defines the cinema of Linklater but the time that encounters between them take to transpire in any space whatsoever. Linklater and his collaborators may play at the generic boundaries of the western, romantic comedy, science fiction, sports movie, musical, documentary and television situation comedy, but instead of making things happen with a stage kiss or a pulled punch they mostly allow time to foster far more intriguing and authentic connections. That said, the cinema of Linklater continues to pull in contrary directions while at the same time insisting that the best way to win a tug-of-war is to let go of the rope. This enthusiasm for genre filmmaking, for example, means that these character-based films stop short of the subtle, enigmatic observations of a filmmaker such as Claire Denis and may even seem hurried and cluttered besides the stripped-down films of the Mumblecore generation that references the cinema of Linklater on their way to that of Yasujiro Ozu; but that’s okay.

Or is it? The cinema of Richard Linklater may observe an American underclass but it rarely contends with the explicitly political causes of their condition. His cinema remains white, straight and well-fed even though it proffers empathy with the underprivileged and marginalised that includes the 34.5 per cent of blacks, 28.6 per cent of Hispanics and 15 per cent of whites currently living in poverty in America (Anon. 2009j). Consequently, one might question the solipsism of slacking and wonder whether remaining in Austin has rendered Linklater a regional filmmaker of diminishing relevance. The fact that slacking is often celebrated as a lifestyle choice might even be considered irresponsible in a country where over 15.5 million people were living below the poverty line in 2007 (ibid.). In retrospect, his is not an outsider cinema such as that boasting queer or black credentials, although he once thanked Todd Haynes publicly during a panel discussion at Austin’s SXSW festival on 17 March 2009 for saying that Slacker could be part of New Queer Cinema because of its alternative notions of time and narrative. The problems faced by the protagonists of the cinema of Linklater are mostly not those of survival but of classical Hollywood genres: how to rob a bank, how to get the girl, how to put on a show, how to rally a sports team, how to break into showbusiness, and so on. While the world was watching the progress to the White House of America’s first black president, Barack Obama (who is a year younger than Linklater) in 2008, Linklater was back in the 1930s with Orson Welles and trying to make it on Broadway. Neither non-white, nor gay, nor poor; instead of a Do The Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989), a Go Fish or a Wendy and Lucy (Kelly Reichardt, 2008), Linklater built a career over almost two decades before taking on the privileged moral issue of vegetarianism in Fast Food Nation. Thus, in considering the cinema of Linklater, one might well ask, where’s the meat?

To be fair, the question of the extent to which any filmmaker is enabled, entitled or obliged to comment on society and its values is one that will often overbalance any appraisal. Linklater never sought the position of spokesperson of the so-called slacker generation and in his subsequent absence from the podium and pulpit it was hardly his fault that MTV and the iPod took his place. Instead of making his own statements, he is more likely to position and enable more verbose philosophers to carry the weight of the word in the films he has directed and sometimes even rotoscopes to add an extra protective layer. As Deleuze says of Godard, ‘he provides himself with the reflexive types as so many interceders through whom I is always another’ (2005b: 181). Perhaps, as Welles (Christian McKay) admits in

Me and Orson Welles, ‘if people can’t find you, they can’t dislike you’. Then again, as Linklater admits, ‘on one level I have to acknowledge now that I’ve made fifteen films and a couple of little side things and, yeah, that’s enough to have to account for it all I guess’. Thus, in formulating this account, it must be questioned whether true social realism, for example, is beyond his scope as a filmmaker; although an expectation of realism misses the point of his cinema entirely. Linklater is, after all, a metaphysician whose cinema often dismisses what passes for reality as a fallible and untrustworthy construct in order to seek truth and fulfilment elsewhere. Instead, by focussing on the

durée (duration) of the

dérive (drift), this cinema posits unreality as something that becomes tangible through imagination, reflection and emotional investment in those who might join one there, even to the extent that the shared experience replaces reality altogether. The metaphysical gambit of Jesse, for example, is to invite Céline to join him for a night in Vienna, while that of Céline is to lead him down twisting alleyways nine years later in Paris. In the same way,

Slacker reterritorialises and so reinvents Austin, as do

Dazed and Confused, SubUrbia, Waking Life, A Scanner Darkly and

$5.15/Hr, while

The Newton Boys revises the glamour of America’s past,

Fast Food Nation reveals the horror of its present and, nonetheless,

Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor and

The School of Rock express hope for its future. Moreover, it is in long takes, fluid camerawork, an emphasis on dialogue and the movement and interaction of the protagonists that this alternative reality is communicated as a viable surrogate to the one experienced by the audience. In

Slacker, for instance, contextual and textual analyses are not separate but interwoven so that the film’s aesthetic carries political resonance. As

Slacker opposes Hollywood narrative with its drifting, incomplete sequences, so the subaltern community in Austin also opposes Republicanism and its identical, analogous obsession with striving for resolution and speculation on the future. When

Slacker is appreciated in the context of the end of Reaganomics and the beginning of the Bush dynasty, it should be recognised that textually and contextually it is a profoundly oppositional film in both form and content and, perhaps most influentially, in the way it simply illustrated an alternative reality to the one that was contemptuous of its carnival of grotesques.

Subsequently, the illustration of an alternative reality was achieved by more explicit metaphysical strategies that employed film itself as an analogy for the dreamstate. If

Dazed and Confused conveys the feeling that every day has the potential to be the worst one of your life, it also ultimately resembles the adolescent fantasy of the best day in Mitch’s life, when this geeky kid spends a night hanging out with the coolest guys in school, buying beer, smoking pot, cruising in cool cars, drinking at a keg party and making out with an older chick till dawn. Consequently, here is proof that the metaphysical strategy has worked, for the film itself aspires to the dreamstate that can be rendered more real than reality itself by the investment of genuine emotion in its potential. As Dawson (Sasha Jenson) says of him: ‘Not bad for a little freshman.’ Time and time again, therefore, the cinema of Linklater shows its audience a way out of conformity and surrender by acting upon imagination. These films are not escapist, but they do present an escape plan. In their possibly naive idealism, they nonetheless hold out the promise of self-determination in a manner that defies all pressures to conform to an unimaginative, unreflective, unemotional life. In addition, their insistence upon human interaction through walking and talking means that they aspire to the standards by which ‘film is made accessible [when] it destroys the luminous cult value or presence of the putatively unique, remote, and inaccessible art project’ (Stam 2000: 65).

Slacker, Dazed and Confused, SubUrbia, Before Sunrise, Tape, Waking Life, Before Sunset, Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor, Inning by Inning: A Portrait of a Coach and

Boyhood are also determinedly collaborative projects in their production process, involving the same core crew repeatedly and the welcoming of their casts’ own investment in their characters even when (or especially when) playing themselves. As an oppositional form of cinema at a time when the mainstream is piling on the bombast, that of Linklater illustrates independence and alternative priorities in its very making.

Such idealism as is celebrated in some of these films, however, is often spoiled by contact with reality in others. Just as the train timetable intrudes so wretchedly upon the otherwise timeless tryst of Jesse and Céline in Before Sunrise, so anxious considerations of one’s place in history and the subservience of the present to the future is what does for the protagonists of The Newton Boys and SubUrbia, in which the fun of robbing banks and just hanging out are both based upon an initial lack of consideration for consequences. This is fine as long as one is able to invest imaginatively and wholeheartedly in one’s immediate legend or ongoing rebellious reputation, but neither the Newton siblings nor the old kids on the block in SubUrbia are able to hold off considerations of ageing that make their behaviour and even existence increasingly anachronistic. From here is but a step inside to the burgeoning paranoia of Tape, moreover, in which two twenty-something males are trapped in the past of a grimy motel room, unable to break free from a cycle of recriminations that has become more important to their identities than the dimly remembered cause of a grievance whose resolution eludes them. However, the means of escape from entrapment in such a stagnant sense of time is illustrated by Waking Life, which evokes aspirations to transcendence through metaphysical gambits that are illustrated by the grotesque rotoscoping of its carnival of philosophers, one of whom, Timothy ‘Speed’ Levitch, is so animated as to make the rotoscoping that adorned him in Waking Life appear redundant when he preaches transcendence to post-9/11 New York in Live from Shiva’s Dance Floor.

However, giving up on the lost cause of converting fearfully conformist adults, the cinema of Linklater turns its attention to the potential of a new generation in

The School of Rock and

Bad News Bears, in which playing for the fun of it rather than the prize is its own form of rebellion. As Augie Garrido demonstrates in

Inning by Inning: A Portrait of a Coach, it is collaboration rather than competition that is the key. It is by celebrating that redemptive, mutual commitment to the moment that Jesse and Céline are rescued from their stalled romance and reunited in real time in the Paris of

Before Sunset. Nevertheless, it seems that such romanticism can only exist outside America, within which the second four-year tenure of President George W. Bush prevents much optimism from emerging in the meagre

$5.15/Hr, the impotent

Fast Food Nation and the ultimately forlorn and paranoid

A Scanner Darkly.

Yet self-assertion through personal growth is revived as a literal ambition in the evolving Boyhood, while the potential for creative expression emerges anew in Me and Orson Welles, in which an analogous period of American optimism to that of Barack Obama’s presidency is identified in the 1930s – a period that was similarly imbued with what Linklater identifies as ‘the spirit of youthful ambition’. Aiming Me and Orson Welles at elusive cinema-goers in 2009, Linklater underlined the analogy when he declared: ‘I want you to feel like you’re a young person in 1937 and the future’s all ahead of you!’ Thus, Me and Orson Welles finds this robust dialogue in the communication of ideas and fosters a cautious commitment to integrity, collaboration and creativity at a time when Obama was campaigning with the promise, ‘Yes We Can.’ All the same, as Linklater admitted, the message of Me and Orson Welles was not immune from the lessons of experience: ‘You can have pure integrity for yourself but you have to take the consequences.’

Way back in Slacker, Linklater appears onscreen in profile behind the film’s opening title with his head against the window of the bus that drives past the golden arches of McDonalds and pulls into Austin at dawn. Identified in the credits as Should Have Stayed at Bus Station on account of the wry conclusion to his monologue on alternative realities and roads not taken, Linklater nevertheless ventures onward into downtown Austin. With its constant arrivals and departures, the bus station is an ‘any space whatsoever’ that signifies a Bergsonian state of mind. It is a place of interaction with countless individuals but little meaningful communication. It is also a place, like a train station in Vienna or an airport in Paris, whose purpose is to offer countless paths away from itself. It resembles, even symbolises, therefore, a billiard-break state of mind based upon an awareness of one’s infinite potential to go in any direction in the eternal single moment. However, although it might seem to be a place of decision rather than chance, there is also scope for bucking the schedule and getting on any bus whatsoever, just to see where one ends up. Had Linklater stayed at the bus station, he may have taken any one of an infinite number of routes leading to different lives that might have included a career in Hollywood or a succession of ‘McJobs’. But the fact that he remained in Austin makes the cinema of Richard Linklater a story of consequences. Asked why he chose to remain there, Linklater replies: ‘It’s home’:

I like Austin more now. I like its music. It’s a very literary, academic environment. And I’m one of the non-nostalgic citizens. The 1980s were really slow here if you had any ambition. There was a depression in Texas and everyone was out of work, but Slacker really grew out of that Austin, you know: lazy, complacent, no economic activity.