introduction

When I began my journey into Witchcraft, I was initially bothered by the athame. Why would a nature religion feature a knife as one of its primary working tools? The symbol of the pentagram, the chalice (or cup), and the broom all made sense to me, but a knife? I associated the knife with negative things; the act of cutting is as destructive as it is useful, after all. As a result of my uncomfortableness with the athame, it was a few years before one found a place on my altar.

When I look back on my initial reluctance to adopt the athame as a working tool, I find myself rather embarrassed. Like the broom and the cup, the knife is a common household instrument. My kitchen has over twenty knives in it, ranging from butter knives to steak knives. While many Witches own elaborate athames, a simple knife is just as effective as a more decorated one. I have one athame that looks as if it belongs in a box with my camping supplies.

In some ways the athame is the modern tool of the Witch. Wands, cauldrons, and brooms have been associated with Witchcraft for thousands of years, but knives not so much. The word athame is of relatively recent vintage too, first showing up in print in 1949. While the word athame may not be particularly old, knives have a long history of use in both magick and ritual. After researching that history, I think the odd thing would be not having a knife on the Witch’s altar.

The athame can often be the source of controversy. There are some who say that it should never be used for physical cutting, and others who treasure it specifically for its practical applications. Like most things tied to Witchcraft, proper use of the athame depends on the practitioner. If it feels right to the Witch “doing the doing,” then the athame is being used properly. Besides, there’s no rule that says a Witch can own only one athame. I keep one in the kitchen and one on the ritual altar.

Along with my sword, my athames are among my most prized magical possessions. I use the athame during ritual, but also for divination. When I cook or bake my “cakes” for the ceremony of cakes and ale (or wine), I often use my athame as a kitchen utensil. I find that it puts a little extra energy into my goodies. The athame is both a practical tool and a spiritual one; its magick brings me closer to the Lord and the Lady and those who have left this world before me.

For those who are just beginning their journey into Witchcraft, I hope this book answers any questions you might have about the athame. The path of the Witch is one of continual discovery. Here’s hoping that my more traveled friends find something new to them in these pages.

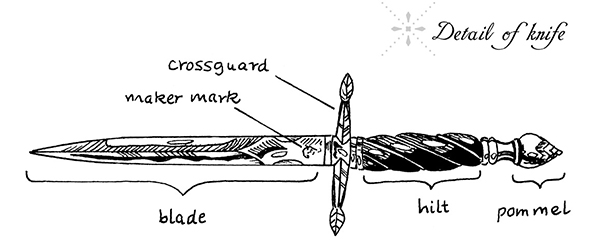

Anatomy of an Athame

To put it simply, an athame is a knife dedicated to magical purposes. Certain traditions mandate the size of the blade and a few other factors, but outside of those specific traditions athames are made from all sorts of materials and come in various sizes. Before delving too deeply into the lore of the athame, it might be a good idea to go over the various components that make up the average athame.

Blade: The blade is the knife’s cutting surface. The average athame blade is made from steel, but several other materials can be used instead. Some of the more common are crystal, stone, wood, and even bone! If it works for you and has a pointy end, it will make a fine athame.

Hilt: Another name for hilt is handle; this is the part of the athame you pick up and hold in your hand. Many hilts are made of wood, but like the blade, they can be made from nearly any material.

Crossguard: The crossguard is where the blade and the hilt meet, and is sometimes called a handguard. On most athames today, the crossguard is both ornamental and practical. If you aren’t paying attention, it keeps your hand from sliding onto the blade. My favorite athame has a crossguard in the shape of two oak leaves.

Pommel: Located at the end of the knife, the pommel is often a raised or rounded end piece. Pommels can be decorative and/or elegantly functional.

Maker Mark: Many blades come with a small symbol already upon them. This is a maker mark, and is generally left by the craftsperson or company that made the knife.

Scabbard: The scabbard isn’t a part of the athame, but it’s what the athame can be placed in. It’s a sheath for the blade. Some athames come with a scabbard, but many do not. Scabbards can be made from just about anything but are usually made from leather, metal, or wood.

Pronouncing the Word Athame

The pronunciation of the word athame varies from place to place and country to country. Witchcraft was initially an initiatory tradition, with its rites and rituals passed from teacher to student, but over the last fifty years it has become more of a “book” tradition. Since most early books on modern Witchcraft didn’t come with a pronunciation guide, people would run into the word athame while reading and then settle on a personal way of pronouncing it. Eventually some of those various pronunciations became common, and most geographic areas have settled on a particular way of saying the word.

In England the word is pronounced “uh-thah-MEE,” and this is probably the original pronunciation of the word. There are various theories on how modern Witchcraft developed, but one thing most people believe is that it began in Great Britain, most specifically England. I once saw a bumper sticker that said “I gave him a whammy with my athame!” which is how I remember the English pronunciation.

I first encountered Witchcraft in the Midwest, where the word is generally pronounced “ATH-uh-may.” Before hearing anyone else say the word, this is how my brain interpreted the word and it’s still the pronunciation I generally use today. After practicing Witchcraft for many years in the Midwest, my wife and I moved to Northern California, where the word is generally pronounced “ahh-thah-MAY.” At this point in my life I generally use the both the Midwestern and West Coast pronunciations interchangeably, though my wife steadfastly sticks to the Midwestern version.

I’ve also heard athame pronounced as a two-syllable word. When this is done, it generally comes out as “ahh-THAME.” The two-syllable pronunciation is the rarest of the various ways athame is pronounced, but it’s certainly not wrong. No matter how you pronounce the word, most Witches will know exactly what you are talking about, and I’ve rarely (if ever) encountered a friendly Witch who corrected someone on their pronunciation of athame.

That being said, I did run into a very unfriendly Witch who liked to “correct” people on how to pronounce the word when they visited her shop. One afternoon while visiting she said to me, “In my very old tradition it’s pronounced ‘ahh-thah-MAY.’” Without missing a beat, I looked back at her and said, “In my two-thousand-year-old tradition it’s pronounced ‘ATH-uh-may.’” As far as I know she never corrected anyone ever again, and no, my tradition is not really two thousand years old, but it was fun to say!

Finding an Athame

A friend of mine bought me my first athame. He had seen me admiring it at my local Witch store and surprised me with it a few days later. It wasn’t the perfect traditional athame, but it was the perfect athame for me at that particular point in time. Traditionally the athame is a straight, double-sided, five-inch blade with a (black) wooden hilt, but mine was far from that.

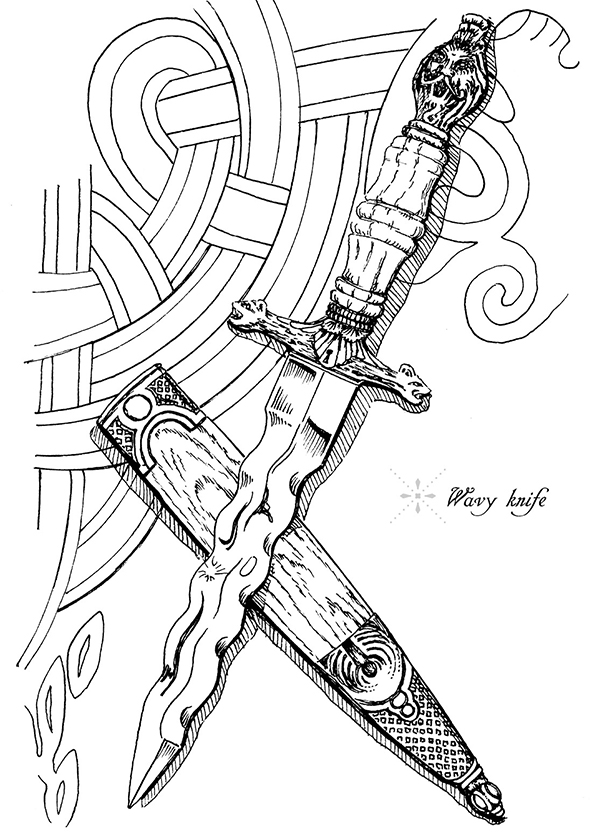

Instead of having a straight cutting surface, my athame had a wavy blade, and was about seven inches long. It had a brown wooden handle with a male face on the pommel (the rounded end of the handle) that reminded me of the Greenman. Old Wavy came with an ornate wooden sheath that always provided a rather dramatic sound and look when drawing him out for use in ritual. I’ve never seen another Witch with an athame like my first one, but I was smitten with him the first time I held him. (I tend to name my athames; I’m not sure if that’s normal behavior.)

Most things radiate energy. Often that energy is subtle, but a good Witch nearly always picks up on it. When deciding whether to purchase or use a ritual tool, it’s important to “sense” that energy. If you pick up an athame and it doesn’t quite feel right in your hands, you shouldn’t purchase that athame. The metal, the wood, the conditions it was created in—all of that is going to have an effect on the energy attached to that particular knife. Old Wavy was manufactured in China and was most certainly not created with the express purpose of being an athame, but he felt just right in my hands.

My wife had a similar experience when purchasing her third athame. We were at a local Pagan gathering and she stopped to look at some blades in the vendor room. At the third table we stopped at, she saw a very traditional athame and just had to get a closer look at it. As it was a pretty expensive piece (two hundred dollars—Old Wavy was about forty bucks), the vendor had to pull it out of a locked case before my wife could examine it.

The second she picked up that knife, she said “oh” and her eyes got bigger. It wasn’t an exceptionally large athame, but it felt so much heavier than it looked. That blade had a presence and a weight that could only be explained by just how much energy was attached to it. When my wife heard the seller’s asking price, she handed the blade back to the vendor, but even though the athame had left her hand, it hadn’t left her heart.

She continued to talk about it as we strolled through the vendor room, and she brought it up again later after we returned to our hotel room. Finally I looked at her and told her to just go buy the thing, so we headed back down to merchant’s row. As fate would have it, “her” blade was still there waiting for her, like I knew it would be.

When purchasing an athame, it’s important to be comfortable with the asking price. It’s said to be bad luck to haggle over the price of a magical tool. If it’s too expensive for you, no worries; you either weren’t meant to have it or weren’t meant to have it at that particular time. The perfect tools always come along at the perfect time.

I’d love for my athame story to have ended with me being completely happy with Old Wavy and walking off into the moonlight with him, but that wasn’t the case. A wavy blade is considered “wrong” in some Witchcraft traditions, including the one I signed up for. Such things were never said aloud to me, but in my tradition blades are traditionally double-edged, with a black handle. My blade did not have a double edge nor a black handle. In order to meet the requirements of my tradition, I would have had to purchase or make a new blade.

Making a new blade was not possible; there was no way my wife was going to let me play with fire and red-hot pieces of metal. I settled for buying a rather ordinary knife with a two-sided blade off the Internet. As far as athames go, it was (and is) perfectly serviceable, but it didn’t really feel like an extension of myself. I even lost it for about ten months, but that loss never really bothered me. It was clear that my “serviceable blade” wasn’t going to cut it at as my primary working tool.

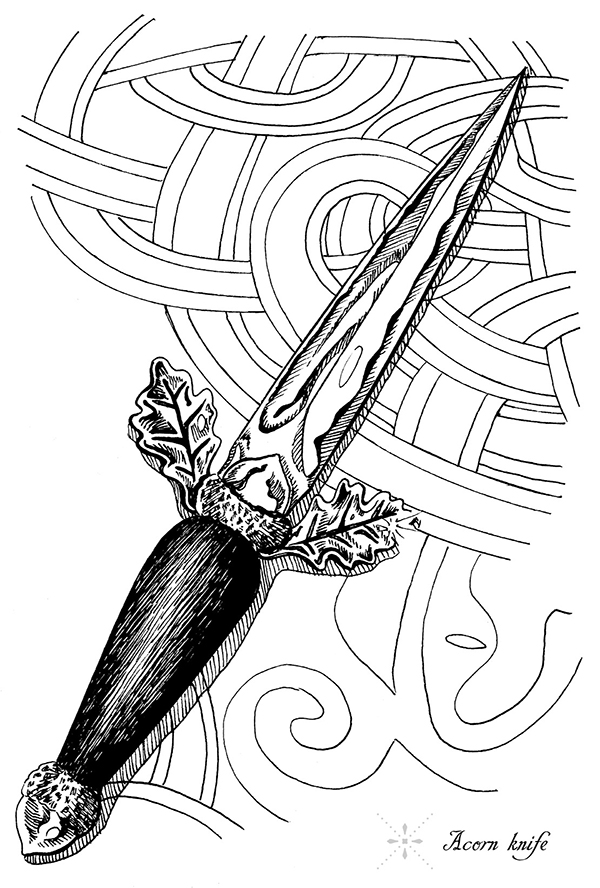

Six months before I began writing this book, I found a lovely athame online that looked absolutely perfect for me. It was double-sided and had the required black handle, but that was only the beginning. Its silver blade emerged from an acorn on the crossguard, flanked by two gold oak leaves, with the pommel also in the shape of an acorn. As the name of my coven is the Oak Court, an “acorn knife” felt particularly apt. It was something I had been hoping to receive as a gift at Yuletide, but since it was a custom-made piece, the wait time on my athame was five months. It ended up being a very long five months.

About a month after receiving my acorn athame, my serviceable brown-hilted knife was returned to me. I was actually happy to see it again, and its return coincided nicely with the writing of this book. Nearly all of the “athame experiments” written about in this book were done on my once “orphaned” blade. It will never be my primary athame, but at least I like working with it now.

Why a Knife? The Practicality and

the Inconvenience of the Athame

It’s easy to find reasons to be uncomfortable with knives. Outside of the dinner table and camping trips, knives are generally seen as weapons, but that’s a rather recent development. As we’ve moved further and further away from our agrarian roots, we’ve had less need for knives in general, but for most of history knives have been an integral part of day-to-day human existence. People used them for a variety of purposes, and they were an extremely common and handy tool.

As a boy (and a Boy Scout), I owned several knives growing up. My favorite was an old pocketknife that I used for a variety of camping activities. I cut rope with it, whittled sticks with it, and even used it for cutlery when eating dinner. It was a constant companion and something that I thought I literally couldn’t live without while in the woods.

For centuries there were many people who really couldn’t live without a knife. They used knives to kill and clean game, cut down branches for shelter, and harvest food. Most pioneers didn’t own guns, but I’m guessing that the majority of them owned a knife. We live in an era where most of us don’t hunt our own food or go out into the wilderness for days and weeks at a time. Seeing someone with anything other than a kitchen knife today is sometimes unsettling, but that’s a relatively recent phenomenon.

The tools of a Witch, above all, are practical. Sixty years ago, a random knife on a small table (altar) was unlikely to elicit much comment. Today it’s probably a bit more noticeable if your athame is more ornate than a steak knife, but the beginnings of every tool used by the Witch are rooted in practical application. The cup, the broom, even a dish of salt—these are all common items that can be used for a variety of purposes.

Because knives can be used as weapons, various states and countries have laws prohibiting their use in public. If you are a public Witch, be sure to check your state and local laws to see whether it’s legal to use a metal blade in a public space (such as a park). Some places even restrict how a knife can be transported in public. If you have to take your athame with you somewhere, it’s best to keep it in your car’s trunk and wrapped in a small towel or blanket.

Many Pagan festivals and Pagan-friendly places like Renaissance fairs allow steel blades to be worn if they are “peace-bonded.” A peace-bonded weapon is one that is tied into its scabbard so that it can’t be drawn. In such instances the sword or knife in question is more of a decorative prop than a magical tool. At some of the indoor Pagan festivals I attend, athames are allowed during ritual but not in other public spaces, and they have to be wrapped up when walking them through the hotel or convention center.

We’ve come a long way since the days when knives were common in public spaces. I don’t think the restrictions on blades in public spaces are going to change anytime soon (if ever), but it’s always worth remembering that knives were common at one point in our history. Just because they are uncommon in a lot of situations today doesn’t mean they were looked at that way one hundred years ago. The knife has a long and mostly noble history, and because of that our athames should sit proudly on our altars and rest mightily in our hands.

getting to the point

Angus McMahan

from 1996–1998, i was the manager of the first witchy store in Santa Cruz County, called 13: Real Magick. In sight of the front door (but strategically at the rear of the store) was the athame case. It was only three feet high—just a small glass-fronted hutch—and it only had space for about eight normal-size blades, if you crammed ’em in, Tetris fashion.

But that little display of glittering prizes was magnetic.

A person would enter our store for the first time and give the place a quick overlook, and then their gaze would fall on those two mirrored shelves—that reflected the BLADES. And our guest would get this sleepy, intense, thoughtless, lustful look on their face. They would stagger through the store, heedless of my greeting (as well as the herbs, books, and incense to their port and starboard), intent only on getting closer—immediately—to the KNIVES. Oh … MY …

And then, just as quickly, their interest would cease after only a cursory perusal of the athames.

We didn’t have their athame. The one for them.

The one.

For no other tool in the basic altar kit is as deeply personal, as receptive, as mutual, as a Witch’s athame. (I suppose there is an argument to be made for wands, but this was the ’90s, and athames reigned supreme in that pre-Hogwarts era.)

Our customers never lingered at the tiny knife hutch. A quick glance would suffice. Is mine here? No. Okay. Someday … soon, maybe …

But every so often, the blade and its owner would find each other. And then the attraction would be downright primal. My employees and I learned to be quick with the keys when we saw this reaction. And sometimes it was difficult to get the Witch to stand back so we could unlock the little glass doors; we were between them and their blade!

And then, the tenderness … the focus … the weighing and balancing … It was almost too personal to witness, like a teenager’s first kiss.

We learned that we could charge almost anything for an athame. Once the knife and its owner had connected, well then, here’s-all-my-money, I have to GO. NOW.

The dirty little retail secret was that the athame case was not a big moneymaker, even with some elevated mark-up on our part. Sales were always slow. Dramatic, intimate, but few and far between. And maddeningly, the connections that were made were always beyond any trends or fashion—so buying the athames from our suppliers was fairly arbitrary. You just never knew what blade was going to click with what Witch.

And we acquired only good-quality, black-handled, double-sided blades to begin with, so our wholesale investment was substantial for each knife. Our favorite suppliers were the ones who touted “no minimum order.”

Cleaning the athame case was always a bit of a chore. For one thing it was small and low to the ground. To play with the knives you had to kneel before the case, which seemed appropriate. But to dust all that mirror and black-handledness was a delicate (and frequent) affair.

And, retail secret here: We often found that we were removing more than just fingerprints, because sometimes our guests would place psychic “holds” on various blades if they couldn’t afford them or were just sloppy with their spellwork. So part of our task list for some days was to wash the athames and freshen their energies.

And don’t forget to lock the glass doors when you’re done!

Angus McMahan

All-around word-jockey and

award-winning storyteller •

www.angus-land.com