The Sword

The first draft of this book included only a 500-word subsection on the sword. When my editor offered her initial critiques of this book, one of them was, “Why didn’t you write more about the sword?” Good question. Why wasn’t I writing more about the sword? I love my ritual sword just as much as I love my athames, and it’s been a part of my rituals on both sides of the United States. (I’ve always wondered what TSA, the Transportation Safety Administration, thinks when they find my sword in my checked luggage.) So what was my initial reasoning for not including a lengthy bit on the sword?

The athame and the sword are inexorably linked. Everything one can do with an athame one can do with a sword, and vice versa. Would enacting the Great Rite with a sword be a bit difficult? Sure, but it would also be completely acceptable. In many ways, a Witch’s ritual sword is simply an extremely long athame, but there’s also a bit about it that’s fundamentally different.

Almost every Witch I know owns an athame. A smaller but still sizable number own a boline. Those two blades are common and easily obtainable, especially the athame. Most Witches I know don’t own a sword. Due to their size, swords are fundamentally more expensive, and more difficult to simply hide away. It’s hard to find a fitting space for a ritual sword in a one-room apartment or a dorm room. Can it be done? Certainly, but it’s a lot harder.

Even some of my teachers and mentors, people who have been practicing the Craft for three decades or more, don’t own a sword. I’ve been a part of covens where everyone brings their athame to ritual, but that’s never happened with a sword. It’s expected that I own an athame, but my swords are seen as a bonus.

So the scarcity of the sword is one of the reasons I initially chose not to write very much about it, but that’s not the only reason. Swords are also often shared by a coven, and used sparingly. In my own coven, we use the sword specifically for casting the circle, and nothing else. The sword we use has been in my possession for eighteen years, but it feels less like my sword at this point and more like it belongs to the coven. In a legal sense I “own” the sword we use in ritual, but I’m rarely the one who wields it in coven situations. There are Witch covens that have been operating for over fifty years, and their sword is continually passed down from high priestess to high priestess. Imagine a sword with fifty years of history, not with one individual but with one group, being wielded by perhaps dozens of Witches over the decades!

This is in sharp contrast to the athame, a tool so personal that most Witches ask before picking up another Witch’s blade. People sometimes ask to borrow my sword depending on the situation, but no one has ever asked to borrow one of my athames. This is the primary reason I was initially reluctant to write about swords in this book. There’s a big difference between the two tools: one is primarily a personal working tool and the other is often shared and used by a variety of individuals.

I often think of the sword as a tool of “high magick,” meaning that it’s more likely to turn up in a circle practicing ceremonial magick than in a coven of Witches. The tools of the Witch are generally easily obtainable (and easily hidden) objects. For much of their history, swords were generally only in the possession of soldiers or individuals with a lot of money.

There’s also a level of seriousness that seems to accompany the sword. In the Golden Dawn, the sword “is to be used in all cases where great force and strength are required, but principally for banishing and for defense against evil forces.” 18 I’ve always taken my athame seriously, but I’ve never thought of it quite in those terms.

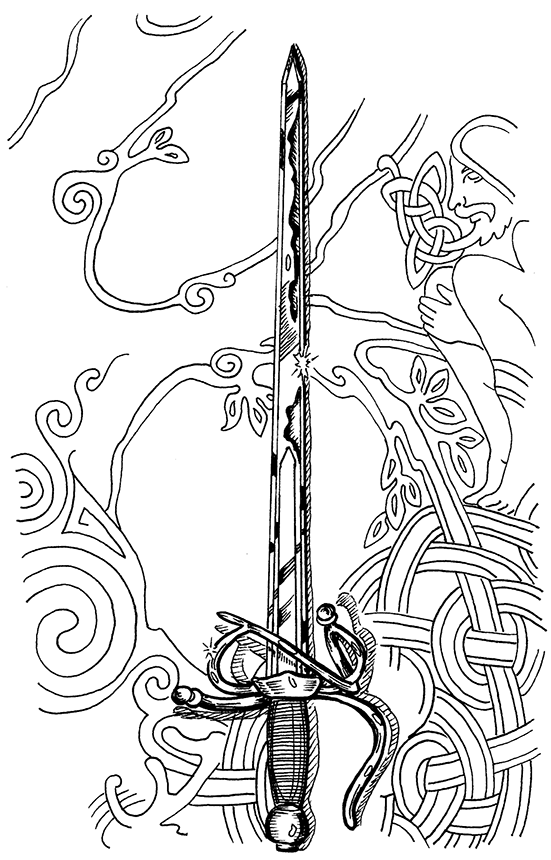

When I use my sword in ritual, it tends to attract a lot of attention, more so than my knife. Part of this might be because it’s old in a way that the rest of my tools are not. I have trouble imagining using an eighty-year-old chalice in ritual, but it just feels right that my sword is over a hundred years old. Crafted in Toledo, Spain, back in 1910, my sword is the only ritual tool I own whose history is a complete mystery to me. Was it used during the Spanish Civil War or in the rituals of a Masonic lodge? Just how did it end up in Detroit, Michigan, with my friend Dwayne, who gave it to me? There’s no other tool I use on a regular basis where such questions would be acceptable, but it feels right with my sword.

Due to its age and (presumed) large number of unknown caretakers, my sword has a certain weariness not shared by my other tools. Everything else I own is in remarkably good condition, but my sword is beaten up and probably a bit rusty. There are several knocks on the blade where it looks like someone tried to use it to chop down a tree. It’s not sharp enough to cut through warm butter, but it always feels right in my hands. For all of its issues, it also has some beautiful scrollwork etched into the blade and has a solidity to it not often found in this day and age.

My old and slightly battered sword

My old and slightly battered sword

My sword looks like it’s been on a journey and has a story to tell, and in that sense it’s very much like a lot of swords throughout history. Few weapons have inspired such love and devotion as the sword. Everyone is familiar with King Arthur and his sword Excalibur. Nearly as well known is Sting, the sword of hobbit Bilbo Baggins, and fans of modern fantasy probably recall that Arya Stark’s sword is named Needle. (Arya is a character in Game of Thrones and steals every scene she’s in.) Few objects possess the magick and mystery of the sword.

The Sword in History

While the sword is lionized today, that hasn’t always been the case. The history of the sword is much more recent than that of the knife. Much of that is because the sword is a far more advanced piece of technology. A sword made of bone or stone is impractical because it will break in short order. Wooden swords are more durable, but they quickly lose their edge. Swords truly require metal, and to be truly effective, they need to be made of iron, and better yet, steel.

Today we think of spears as primitive weapons, but in the ancient world they were a primary weapon. The pottery of the ancient Greeks, for instance, depicts a whole lot of spears and very little in the way of swords. Certainly there were a lot of soldiers who carried swords, but those swords were very much a secondary weapon. Even the Romans primarily used the spear for much of their history, generally because sword technology was still rather limited. Early swords were made of bronze, a metal alloy consisting primarily of copper and tin. Bronze swords were eventually replaced with swords made of iron.

Bronze and iron are both so important in the development of human civilization that they have ages named after them. Bronze Age cultures existed from 3300 BCE and up until 600 BCE in parts of Europe. The Iron Age began as early as 1200 BCE in some places and lasted until 700 CE in others. The terms Bronze Age and Iron Age are problematic because every civilization had its own individual Bronze and/or Iron Age. Just because iron was being used in Rome doesn’t mean it was being used in Germany. In Europe, the Iron Age ended in the year 1 CE, the beginning of the modern era, or Common Era (CE).

The ancient Greece of mythology and Homer’s Odyssey is a Bronze Age culture, and swords from the period are common in museums and can even be purchased by private collectors. Bronze swords were sharp and mostly durable, but bronze just wasn’t strong enough to make the sword a primary weapon. Swords in battle often bent, which was not ideal in combat. There are humorous stories of bronze weapons having to be straightened out on the battlefield; it’s no wonder spears held sway for such a long period of time.

Early iron swords weren’t much better than bronze. While they didn’t bend as much, they often were brittle and were more likely to shatter. As technology improved, so did the sword, and eventually the Romans were able to manufacture quality steel swords like the gladius. The gladius was a strong short-sword that was an effective tool for both stabbing and hacking.

The sword as we generally think of it today came of age during the (European) Middle Ages (500–1500 CE). Utilizing technology borrowed from the Middle East, European blacksmiths began making high-quality swords. When we think of swords, we tend to think of knights, and that’s because the sword rose to prominence during the Age of Chivalry, where it became immortalized in history, myth, and legend.

Swords in Mythology and History

Swords existed in mythology before the Middle Ages, but on a much more limited basis. Greek and Roman mythology is full of heroes, but they didn’t wield swords like Excalibur. The most famous sword in Greek mythology is famous not because it was wielded by a brave warrior but because it became a popular metaphorical expression.

The Sword of Damocles was the name given to a sword suspended by a single horsehair over the throne of the Sicilian tyrant-king Dionysius II. In order to prove to the philosopher Damocles just how difficult ruling was, Dionysius allegedly offered Damocles his throne. But the throne came with one caveat: a sword suspended over the philosopher’s head. The sword served as a constant reminder of just how difficult rule could be, and that the rich and powerful often face problems that are overlooked by those envious of their status.

In Greek myth, the hero Theseus comes of age by moving a large rock and taking up his father’s sword and sandals. In this case, Theseus’s father is Aegeus, the king of Athens, and the sword signifies his heir-in-waiting status relative to the city-state’s throne. Due to their rarity, swords in Bronze Age Greece conferred status. Theseus later used his father’s sword to kill the dreaded and legendary Minotaur.

Though the sword features in Greek and Roman myth periodically, it reached legendary status in the myths of the Middle Ages. The sword features prominently in the myths of King Arthur, along with the Welsh and Irish myths that preceded and influenced the stories of the Knights of the Round Table. Norse and Anglo-Saxon myths also reference the sword. Many of the most popular and legendary figures of the Middle Ages possessed magical swords.

Excalibur is probably the most celebrated sword in all of mythology, but its history is a bit more tangled than most people realize. There are even two different versions of how Arthur obtained his legendary sword. The best-known version is “the sword in the stone” tale, where only the true king of the Britons can remove Excalibur from a large rock. Originally the sword was encased in an anvil, before being changed into a stone in later versions of the tale.

In the story of King Arthur, Excalibur represents justice, and the rock it was drawn from is symbolic of Jesus Christ. By pulling a sword of justice from a stone representing Christ, Arthur establishes himself as a king by divine right.19 In some versions of this story, it’s the knight Sir Galahad who removes a sword from a stone in preparation for his quest for the Holy Grail.

In the more magical version of how Arthur received Excalibur, he’s given his sword by the mysterious Lady of the Lake on the Isle of Avalon. In that version, a hand breaks the surface of the lake and throws Excalibur and its scabbard to him. While Excalibur established Arthur as king, it was the sword’s scabbard that was truly magical. The scabbard was said to protect its wearer from physical harm, but that bit of magick just doesn’t capture the imagination like a powerful, shiny sword. Celtic swords were often more magical than the swords in other mythologies, with some even capable of song during battle!

Ties between Celtic myth and the stories of King Arthur are tedious at best, but Excalibur has several parallels in Welsh mythology. The swords Caladbolg and Caledfwich are often compared to Arthur’s legendary blade, with the latter even appearing in both Celtic and Arthurian tales.

Norse mythology is full of swords, though none of them are quite as famous as Thor’s hammer, Mjölnir. (Curiously, in some version of Thor’s myth, Mjölnir isn’t a hammer at all, but an ax, another weapon with a sharp blade.) Swords in Viking mythology were generally prized for their strength and not their magical properties, though any sword capable of killing a dragon would have to have been infused with some degree of magick.

The creation of a sword was often seen as a magical event, and sometimes the smiths who forged famous swords became just as legendary as the heroes who wielded them. The most famous smith in all of European mythology is probably the Anglo-Saxon/Norse Wayland (often spelled Waland and sometimes Wieland), whose legend existed across Europe. Wayland has been known to show up in the mythology of the Franks, Anglo-Saxons, and the Norse and is still a popular figure in modern fantasy literature.

Wayland was more than a smith; in some myths he was also the Lord of the Elves! His legend was so powerful that he made swords for more than just gods and heroes; several historical figures also have swords attributed to Wayland. Durendal, the sword of Roland, nephew of the emperor Charlemagne, was said to have been made by the legendary smith. Wayland also shows up in the Norse Edda and the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf.

Famous swords weren’t just reserved for mythological and pagan figures. In Islamic tradition, Ali, the son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad, wielded the legendary Zulfiqar. Ali’s sword is one of the more unique swords in history and legend, and is often depicted as having two points (looking a lot like an open pair of scissors). Zulfigar was a gift either from Muhammad or from the angel Gabriel.

In Christian tradition, a whole host of famous personages have had famous swords. The Frankish Emperor Charlemagne wore Joyeuse at his side, a sword so special it was said to shine brighter than even the sun. Eventually French kings used a sword purported to be Joyeuse at their coronation ceremonies.

The two most popular figures in Christian tradition after Jesus himself are both associated with the sword. The Apostle Peter actively used a sword in the New Testament, cutting off the ear of a servant (or slave) named Malchus. That sword allegedly still exists at a basilica in Poland (scholars today believe it to be a medieval forgery). The Apostle Paul is the “saint of swordsmen,” and his symbol in the Roman Catholic Church is a sword positioned in front of a book.

The Wallace Sword, said to belong to the legendary Scottish freedom fighter William Wallace, is currently on display at the national monument that bears his name. It’s unlikely that the sword actually belonged to the character depicted in the movie Braveheart because it’s just too big. It’s a two-handed sword with a blade over five feet long! To effectively wield what is today known as the Wallace Sword, Sir William would have had to have been unusually tall for his era.

Not only did the sword rule the Middle Ages, but it seems to rule the modern-day world as well. In fact, swords might be more popular today than they were a thousand years ago. They show up in books and are also part of several movie and video game franchises.

The Harry Potter series is probably best known for its use of the wand, but it makes room for blades as well. The Sword of Gryffindor plays a large role in J. K. Rowling’s story, and Harry (along with his friends Ron Weasley and Neville Longbottom) uses the sword several times along his way to defeating the evil Lord Voldemort. The wands in Harry Potter are certainly cool, but I’d much rather have that Gryffindor sword!

We don’t usually associate science fiction with swords, but they often show up there anyway. The most famous sword style of the last thirty-five years might be the lightsaber. It’s no coincidence that Jedi “Knights” wield a weapon that looks remarkably similar to a sword. Blasters might be practical, but they lack the romance of a blade. My favorite sword duels are just as likely to involve Darth Maul, Luke Skywalker, and Yoda as they are King Arthur.

With over fifty million units sold, the Legend of Zelda video game franchise is one of the biggest in the industry. Central to the game is the Master Sword (or Skyward Sword) utilized by Zelda’s hero, Link. In the Super Smash Brothers spinoff, Link’s weapon of choice is also the sword. Zelda isn’t the only series of video games to use swords; the weapon is central to games like Dragon Quest and entire online universes like that found in World of Warcraft.

J. R. R. Tolkien’s Middle-Earth is home to several famous swords. The most famous is probably the glowing-blue Sting first used by Bilbo Baggins in The Hobbit and then later by his nephew Frodo in the Lord of the Rings trilogy. More powerful than Sting was Gandalf’s Glamdring, which glowed white when in the presence of orcs. The sword Andúril, wielded by the hero Aragorn, was capable of stabbing both the living and the dead, and, just like Excalibur, indicated kingship.

In the series Percy Jackson and the Olympians, the protagonist (Percy Jackson, of course) also wields a sword. Since swords are pretty cumbersome and don’t fit in your pocket, Jackson’s sword Riptide turns into a pen when he’s not using it. Author Rick Riordan’s Jackson books are introducing a whole new audience to the Greek gods, and there’s no better way to introduce people to that mythology than with the sword as your hero’s primary weapon.

High fantasy has turned into big business since the release of the Harry Potter and the Lord of the Rings movies, and that means we are only going to see more swords in the future. No other weapon in history has been as romanticized as the sword, and I’m reminded of that every time I see the Witch’s circle cast with one.

Sword Lore

The sword has long been a symbol of royal power, and this has continued into the present day. When a new king or queen is crowned in Great Britain, there are five different swords used in the coronation ceremony. All five swords are also considered part of the United Kingdom’s “Crown Jewels.” One of those swords, the Curtana (or Sword of Mercy), dates back to the thirteenth century, and the largest sword in the collection, the Great Sword of State, is used annually to open Parliament.

Beginning in the Middle Ages, Christians used to swear and take oaths on a sword most likely because it resembles a cross. Those who swore on a sword generally did so at the intersection of the guard and hilt, the most cross-like part of any sword. For Witches, this is all of little consequence, but the image of a knight kneeling on one knee in front of a sword, with his hands on the top of his sword, is one that is recognizable in all sorts of mythology and literature.

Perhaps due to their rather aggressive and masculine energy, swords have been involved in several different courtship rites throughout the centuries. Prospective grooms who were lucky and rich enough to own a sword in the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance often popped the question by presenting a wedding ring on their sword’s hilt. No doubt the sword hinted at the groom’s virility and strength.

Even more virile is a Norwegian tradition that involves the groom plunging a sword into the ceiling beam of a house. A good strike guaranteed a productive and successful marriage, and a bad one was seen as a sign of potential trouble and, more quietly, future impotence on the part of the groom. This tradition lasted into the eighteenth century, so it’s not all that far removed from the modern world.

While swords were certainly seen as symbols of masculinity and power, they also had the power to prevent copulation. In the legend of Tristan and Iseult (dating back to the eleventh and twelfth centuries), the couple is sometimes cleared of the crime of premarital sex because they kept a sword between them while sleeping. The idea that a sword might prevent a couple from making love is present in several Western cultures. The idea is found among the Norse and Arabic as well as the French and Irish sources that inspired the stories of Tristan and Iseult.

In Taoism, swords are used to cleanse and purify altars, ridding them of negative energies. Because swords are so beloved and honored by many Taoists, China has a great deal of sword folklore. It’s considered bad luck, for instance, to place a sword on the ground or partially unsheathe a blade. When someone offers a blade to you, it’s considered proper form (and good luck) to accept the sword with both hands.

In China and Japan, swords are thought to have something akin to souls, and as such people often honor them with offerings. Gifts such as flowers or scented oils will draw good spirits and energies into your sword, while gifts of blood or red meat will draw more negative entities. In some Eastern traditions, it’s important to give your sword an offering so it won’t turn on the one wielding it.

I’m not sure that there’s a spirit hiding in my sword, but there is a lot of energy. Much like my athames, I think that my sword has a definite personality, and the more I think about it, a gift or offering to my sword is probably a good idea. It certainly couldn’t hurt!

Blessing a Sword for

Coven Work or Group Ritual

Swords are one of the few working tools often shared by an entire coven. Because of the sword’s unique nature, a group blessing can help every covener take a small bit of ownership in a shared group sword

Before blessing the coven sword, make sure it’s properly consecrated. The consecration ritual in chapter 4 of this book is a great place to start. The consecration and group blessing of the coven sword can be done back to back or over the course of a few gatherings. The best lunar phase for tool consecration is the new moon, as it symbolizes and empowers new beginnings. For blessings, a moon of abundance is the best choice, with the full moon (or time around the full moon) being optimal. Sometimes waiting for lunar phases isn’t practical, but when you can do so, I think it adds a little extra oomph to the rites.

This particular blessing is designed to do two things for the sword and those in the coven:

1. Familiarize everyone in the coven with the sword’s own unique energies and introduce the sword to the energies of everyone in the coven. We all make introductions to those individuals with whom we practice the Craft, so why not also introduce ourselves to the tools we will be using?

2. Give everyone in the coven a bit of ownership in the sword. Unless your coveners have all chipped in together to buy a new sword, it’s likely that the coven sword has one individual owner who is allowing the whole coven to borrow it, so to speak. In my own coven, that’s our situation. Our sword is technically mine, but I want everyone I circle with to feel a bit of an attachment to it. It’s a very important tool in ritual—it’s what takes us between the worlds! That’s a pretty big deal, and I want my covenmates to know that as long as we are performing ritual together, the sword is also “theirs.”

At the start of the blessing rite, the sword should be in the hands of the coven’s ritual leader. She should begin by slowly walking around the circle deosil (clockwise), with the sword stretched out before her almost as if she was in the process of casting a magick circle. As she walks, everyone in the coven should take a few moments to really look at the coven sword. They should notice its newness, or in some cases, the wear and tear it has endured over the years, decades, or centuries. Those looking should reach out to the sword with all their senses to see if they can detect a bit of its history or energy.

As she walks around the circle, the high priestess should make some remarks about the coven sword and the role it plays in the coven.

With this sword we travel between the worlds. It is our gateway into a time that is not a time and to a place that is not a place. This sword is our gateway to the lands where both gods and mortals dwell. Because this sword transports all of us in this coven to that magical realm, it’s important that we all feel an attachment to it, that we all know this sword, and that it knows us.

The priestess should now return to her customary place in the circle. Once there, she should hold the sword out and away from her body horizontally, with one hand on the hilt and another on the blade. (She should do this if the blade is not sharp. If it is sharp, the sword should be held vertically with the point facing downward.) Holding the sword comfortably but with power and authority, she should say:

This sword was born in fire, and tonight it is blessed and reborn in service to this coven! One by one we shall bless our coven sword and share with it our energy. By doing so, it will better recognize those who stand here and better work with our own energies.

The priestess should now slowly tip the sword downward so that its point lightly touches the floor. When the sword is in the proper place, she should continue:

When the sword is passed to you, slowly lower the point to the floor and then push a bit of your own energy inside of it. Feel the energy flow from you down through your hands and into the hilt and then the blade. Be sensitive to that energy as it descends down the blade. When you feel it reach the point of the sword, open yourself up to the sword’s energy and feel it travel up the length of the blade until that power touches the hilt and then you. Once the energy has returned to you, speak a truth about how our sword will be used in ritual.

The sword should be slowly raised off the floor and then handed horizontally to the coven member on the priestess’s left, the sword now moving around the circle deosil. Coveners can say whatever they wish after exchanging energy with the sword, but here are a few ideas:

With this blade we shall walk between the worlds.

This sword is our gateway to the mysteries.

With steel and iron at our side, we shall be safe

in this circle from all that would wish us harm.

This is the key that shall unlock the magick

of the Lady and the Lord.

To journeys past and the journeys that await.

In perfect love and perfect trust

we walk this path together.

Thou art an entryway to the land of spirit.

May this sword always lead us

toward love, joy, and truth.

From this blade, power and wisdom.

May this sword always be a light that will help to return us all home to this coven.

A shield against all wickedness and evil.

May this sword assist in the work

and legacy of this coven.

Together we share this sword, and it a bit of us.

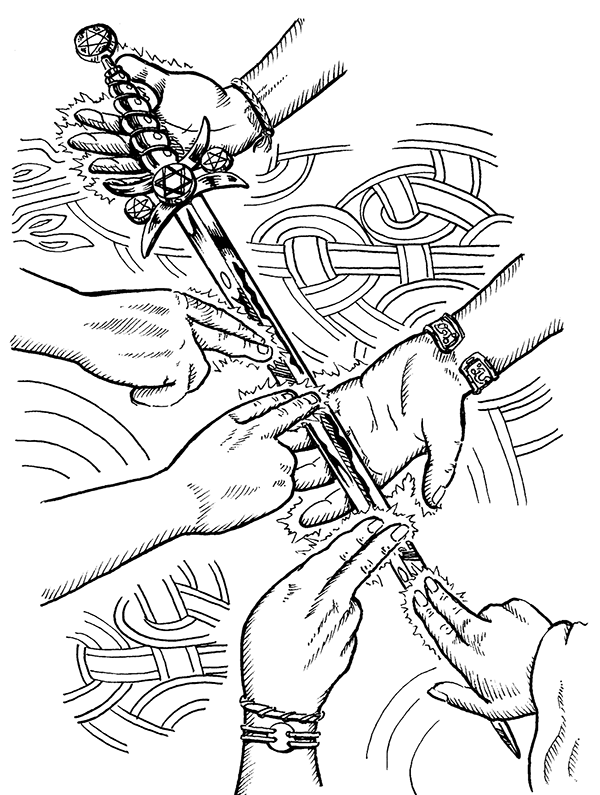

Once the sword has been passed around the coven and returned to the high priestess, she should hold it over the center of the altar and instruct everyone to gather around it. Once the coven has been gathered, everyone but the high priestess (who is holding the sword) should hold their middle and index fingers to their lips and share a kiss with the sword. (Fingers should be kissed and then brought down to the sword.)

With everyone touching the sword, the priestess says:

Together we have blessed this sword that it might better serve our coven. In perfect love and perfect trust we close this rite with the words: so mote it be! (So mote it be! is repeated by the coven.)

The sword has now been blessed and should be returned to its customary place on the altar until it is used to release the circle.

Many hands touching a sword as a form of blessing

Many hands touching a sword as a form of blessing