Figure 1

The political stakes of correlationist poststructuralism

Generally the debate between correlationism and speculative realism as well as new materialism has taken the form of whether or not and to what extent we are capable of thinking the absolute (that which is not correlated to a subject). Does everything have an intrinsic essence (strong realism)? By ‘intrinsic essence’ I mean that the properties of a thing truly belong to that thing themselves and do not arise from the cognitive or social agency that categorizes those things. This would seem to be what Harman’s object-oriented philosophy (OOP) sometimes seems to defend with the claim that all objects have an essence, albeit withdrawn.1 Are some properties ‘by-products’ and others ‘connected’ (weak realism)? This is the position I advocate, along with thinkers such as Lucretius and Ian Hacking.2 Here, some entities and properties like value, gender, ethnic identities, social roles and so on would be constructed, while others would have independent existence. Or is it the case that all entities and properties are constructed or the result of correlations, such that there are no beings independent of observers?

In what follows I would like to reframe the rather academic debate between correlationism (or antirealism) and realism in terms of the political stakes that lurk behind these abstract positions. First I will outline the set of considerations that have led radical emancipatory political thought to favour the correlationist or antirealist framework and why, against the position of theorists such as Graham Harman, some variant of correlationist thought is worth preserving. I will then outline how Luhmann’s theory of distinctions and systems theory, due to its abstraction and generality, provides us with the most thorough articulation of correlationist thought to date, allowing a wide body of diverse theory to be integrated according to a shared logic. Having developed this framework, I will then show how correlationist thought encounters difficulties dealing with the power exercised by material agencies that do not arise from correlations and that are crucial to understanding climate change, material features of environments and the impact of new technologies. Materiality acts not by virtue of signification, as correlationists contend, but by virtue of what it physically is. Correlationism tends to veil or render invisible these latter forms of agency. Finally, I conclude with a deconstructive reading of Luhmann, using his own theory of distinction and second-order observation to disclose the blind spot of correlationist thought and how this thought, despite itself, is led to realist claims. This deconstruction is not a destruction, but rather aims at a sublation that would allow us to retain what is best in correlationism when its proper limits are specified while also opening the way to the role played by material agencies in social assemblages.

It would be a mistake to think that there is anything like a unified philosophical position shared by those thinkers falling under the titles of ‘speculative realism’ (SR) and ‘new materialism’ (NM). The term ‘speculative realism’ arose as a compromise among participants at a conference devoted to realism and materialism held at Goldsmiths in April 2007.3 While there was a shared commitment to realism and/or materialism by Ray Brassier, Iain Hamilton Grant, Graham Harman and Quentin Meillassoux, these positions differ from one another.4 Each of these thinkers holds quite distinct positions that are in many respects opposed to one another. In short, there is a debate among speculative realists as to what constitutes the real and the material. As noted, like OOO, SR is a genus rather than species term, with debates among these thinkers as to just what the real is. The case is similar with NM, where thinkers such as Jane Bennett, Manuel DeLanda, Karen Barad, John Protevi and Stacy Alaimo, to name but a few, all share a commitment to exploring materiality while nonetheless proposing differing accounts of it.

What unites the speculative realisms and, to a lesser degree, the new materialisms – the plural here is crucial – is not a shared ontology but an opposition to what Quentin Meillassoux calls ‘correlationism’. As defined by Meillassoux, correlationism is ‘the idea according to which we only ever have access to the correlation between thinking and being, and never either term considered apart from the other’.5 He continues:

[c]orrelationism consists in disqualifying the claim that it is possible to consider the realms of subjectivity and objectivity independently of one another. Not only does it become necessary to insist that we never grasp an object ‘in itself’, in isolation from its relation to the subject, but it also becomes necessary to maintain that we can never grasp a subject that would not always already be related to an object.6

Meillassoux contends that it was Immanuel Kant who first inaugurated the correlationist turn. Although there were precursors, Kant announced the correlationist shift with his Copernican turn. As Kant remarks:

Up to now it has been assumed that all our cognition must conform to the objects; but all attempts to find out something about them a priori through concepts that would extend our cognition have, on this presupposition, come to nothing. Hence let us once try whether we do not get farther with the problem of metaphysics by assuming that the objects must conform to our cognition.7

With Kant we get a deontologization of reality insofar as the thesis that objects conform to mind entails that we can never know what objects are in themselves, but only phenomena presented to mind. Phenomena are produced by the distinctions supplied by mind. Whether those distinctions correspond to reality apart from mind can never be known. Nonetheless, for Kant something like reality is preserved insofar as there is a universal structure of mind that we all share. The project of transcendental idealism consists in uncovering and articulating this structure.

What, then, should we understand by the ‘deontologization of reality’? ‘Deontologization’ means that the properties we encounter in objects do not belong to the things themselves, but rather are contributed by mind. This is the core of the correlationist or antirealist position: what appeared to belong to the things themselves instead is contributed by us. Correlationism is not then the thesis that a subject must relate to an object to know that object. Every realist has advocated this claim. Rather, correlationism is either the thesis that (a) we can never determine whether the properties we attribute to things truly belong to the things themselves because we cannot determine what is contributed by our minds and what is contributed by the things themselves (weak correlationism); or that (b) it is, in fact, mind that structures reality such that properties are not contributed by the things themselves but rather things are the products of mind (strong correlationism). As Kant puts it, arguing for a rather strong variant of correlationism, ‘the a priori conditions of a possible experience in general are at the same time conditions of the possibility of the objects of experience’.8 For Kant, it is not just that the categories and forms of intuition structure our cognition but that they also constitute the objects of experience. In the B edition Kant will drive this point home, remarking that:

[s]pace and time [and the categories] are valid, as conditions of the possibility of how objects can be given to us, no further than for objects of the senses, hence only for experience. Beyond these boundaries they do not represent anything at all, for they are only in the senses and outside of them have no reality.9

Here we have the core of the correlationist thesis. It is not merely that a subject must relate to an object to know it; rather, that subject actively constitutes its object such that the object has no being or reality apart from subject. There might, of course, be being or reality apart from the subject – what Kant calls ‘noumena’ – yet we can know nothing of this and our categories and forms of intuition certainly do not mirror this reality. There is only ever reality ‘for us’, never reality in itself.

In addition to strong and weak correlationism we can also distinguish between universalist and pluralist correlationisms. Universalist correlationism holds that while the mind is not a mirror of reality because, in fact, it constitutes beings through its cognitive activities, there is nonetheless a universal reality because the structure of mind is the same for all rational beings. The task of universalist correlationism would thus consist in uncovering this universal structure of mind. In Kant, for example, this would consist of the articulation of the twelve categories, the forms of time and space, as well as the various ways in which these elements are synthesized to produce reality. Similarly, Claude Lévi-Strauss’s structural anthropology would be a variant of universalist correlationism insofar as it seeks to determine the universal structures of thought; while Husserl, under one reading, would be another. By contrast, pluralist correlationism would argue that there are no universal structures of mind but rather a variety of different structures. As a consequence, it would reject the thesis that there is one ‘reality’, for there would be no one way of constituting objects. Here the correlationisms would be called ‘contingent’ because, first, they would be the result of a history and, second, they would always be capable of being otherwise. Pluralist correlationism is the form taken by poststructuralist thought.

It is always, of course, possible to find exceptions, but Continental thought has largely been dominated by one form of correlationism or another.10 However, whether reference is made to phenomenology or poststructuralism, correlationism is certainly the dominant or molar tendency within Continental thought.11 Here it is likely that Heideggerians and poststructuralists will object, pointing out that Dasein is not the (Cartesian) subject, and that much poststructuralist thought describes, to use Althusser’s famous phrase, process without a subject. However, it is important to note that it is not correlation to a subject that is crucial to Meillassoux’s concept of correlationism. We can just as easily replace the term ‘subject’ with ‘language’, ‘power’, ‘Dasein’, ‘body’, ‘sign’, ‘discourse’, ‘society’, etc. Paraphrasing Meillassoux’s descriptions of correlationism presented elsewhere, a position is correlationist if it argues that there is no X without givenness of X to Y, and no theory about X without Y positing X.12 It matters little what we plug into the space of Y (the subject-function), so long as we make the claim that X cannot be thought without Y.

Correlationism ineluctably leads to some variant of idealism (of which social and linguistic constructivism are variants), for the claim is that we cannot speak of being independent of its relation to human being, whether in the form of a subject, a transcendental ego, a cogito, language, signs, power or economy. The practical imperative that arises from correlationism is the command to ‘observe the observer’. I will have more to say in justification of this characterization in a moment, but what is important for now is that correlationism directs us to investigate how being or objects are given to a particular society, language, subject, configuration of culture, system of signs or subject. Correlationism calls us to investigate how the object is given to a subject (or whatever else appears in the position of Y).

Yet strangely, despite the thesis that we cannot think an object apart from a subject, the object quickly disappears in correlationism. For in directing us to observe how the object is given to a subject, to observe how an observer observes, we very quickly recognize, under pluralist correlationism, the sheer contingency of observers. Reality, we notice, can be structured in a variety of different ways and has, in fact, been structured in different ways at different points in history or by different cultures. As such, any particular version of reality is just that, a version, and therefore contingent. Other structures are always possible. We are thus led to suspect that perhaps there is no in-itself or object at all, but rather that the subject somehow constitutes or creates its object. What is given for one set of subjects, for example, might not exist for another set.

Put differently, correlationism leads us to conceive the in-itself, the absolute, or being apart from a subject as a sort of undifferentiated continuum that is then cut up or individuated by some form of human agency. Given that we saw above that language, society, etc. can be placed in the slot of ‘subject’ in the structure of correlationism, it might seem odd to suggest that pluralist correlationism inevitably argues that some form of human agency structures reality. However, to our knowledge, language and society only exist for and are only produced by humans. Thus, regardless of how antirealist a humanism might claim to be (as in the case, for example, of Althusser), it is still a humanism at the end of the day. From the correlationist standpoint, beings are what they are as a result of some form of human agency.

Here Marx’s analysis of commodity fetishism in Capital provides a prototypical example. We begin by taking the value of the commodity as a feature or quality of the commodity itself – a realist stance with respect to value. We think that somewhere, within the diamond itself, dwells this property of being valuable, such that the diamond is intrinsically valuable. What Marx effectively demonstrates is the manner in which value is not a property of the diamond itself, but rather a feature that arises from social relations involved in producing the diamond:

the commodity-form, and the value-relation of the products of labour within which it appears, have absolutely no connection with the physical nature of the commodity and the material relations arising out of this. It is nothing but the definite social relation between men themselves which assumes here, for them, the fantastic form of a relation between things.13

The value of the diamond is not something that resides in the diamond but rather something that only arises in relation to a subject – in this case, the socioeconomic system presiding over production. Put differently, value is not something intrinsic to the diamond itself. As an aside, the example demonstrates why, in my view, we should take care not to reject all forms of correlationism: there are phenomena for which correlationist accounts are perfectly appropriate, such as value in the case of the commodity. Diamonds have no value for cats, but only for humans.

Marx’s critique of commodity fetishism and the correlationist thesis upon which it is based can be seen as the elementary schema of all critical theory. The basic gesture of critical theory and emancipatory political thought consists in showing that some property we took to be a feature of the thing itself is in fact a construction of social relations. As Lucretius wrote in the first century bce:

Whatever exists you will always find connected

To these two things, or as by products of them;

Connected meaning that the quality

Can never be subtracted from its object

No more than weight from stone, or heat from fire,

Wetness from water. On the other hand,

Slavery, riches, freedom, poverty,

War, peace, and so on, transitory things

Whose comings and goings do not alter substance –

These, and quite properly, we call by-products.14

Lucretius here draws a distinction between properties that belong to the things themselves (real properties) and properties that arise from a correlation with a subject. It might initially seem difficult to see just why such an abstract distinction between types of properties and the debate between realism and antirealism would be crucial to emancipatory politics. However, it is important to note that defences of dominant power structures are always based on an ontology that asserts that oppressed groups are not oppressed at all because the real or intrinsic features of their being entail that they should occupy their allotted place within the social order. For example, in his defence of slavery, Aristotle writes that:

where … there is such a difference as that between soul and body, or between men and animals (as in the case of those whose business is to use their body, and who can do nothing better), the lower sort are by nature slaves, and it is better for them as for all inferiors that they should be under the rule of a master.15

Aristotle’s thesis is that inferiority is an ontological, natural, connected or intrinsic feature of such persons and that therefore their status as slaves is both justified (by nature) and even desirable for these individuals themselves. The stakes of the debate over the status of these properties is thus quite clear. If these properties are ‘connected’, then the hierarchies we find in the social order are ontologically natural and therefore just. No doubt this is why so many critical theorists and poststructuralist correlationisms (PSCs) are suspicious of ontology. Far from being ‘natural’ or essential properties of persons, they take such properties to be historical social constructions and to represent unjust distributions of power.

The gesture of critical theory and poststructuralist thought will thus consist in the careful demonstration of the contingent, historical being of these predicates and how they are capable of being otherwise. For example, through exacting historical analysis, Michel Foucault will show how systems of power generate particular forms of subjectivity, while Judith Butler will show how gender, far from being a connected biological property of persons, is, in fact, performative or the result of the enactment of discursive systems inherited from the culture into which one is thrown.16 Perhaps more dramatically, Jacques Derrida will show how the foundational concepts of philosophy, far from being founded on identity, instead result from a precarious play of differences that prevent univocal meaning (and therefore fixed reference) from ever being established.17 Examples could be multiplied. Like Marx showing that the value of the commodity is, in reality, a product of social relations and Lucretius showing that predicates like slavery are by-products of correlations rather than intrinsic features of persons, the poststructuralists demonstrated the constructed nature of these predicates. If, then, it turns out that these properties are the result of correlations, it is possible for them to be otherwise and one can set about constructing new forms of life that would escape from these social hierarchies. We can thus see that the stakes of the issues surrounding the seemingly abstract issue of correlationism or the debate between realist and antirealists is quite high; and it is for this reason that SR’s critique of correlationism and defence of realism has generated so much controversy within critically minded thought in the humanities.

Luhmann, second-order observation and the logic of correlationism

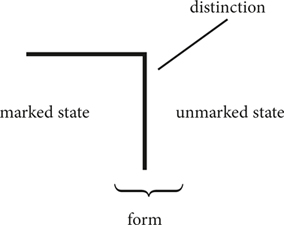

Throughout the foregoing I have sporadically referred to observers in my discussion of correlationism. Correlationism does not take observations at face value, but instead invites us to observe the observer and what the observer contributes to that which appears. It is here important to clarify the concept of observation, as this will help to shed light on the correlationist controversy and why there has been a renewal of realist and materialist orientations of thought. I draw the concept of observation from Niklas Luhmann, who retools the concept from Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela’s reworking of George Spencer-Brown’s account of forms. It’s important to note that ‘observation’ does not here refer to the five senses, nor even to living beings, but rather to a highly formal operation that consists in drawing distinctions. It is not the possession of organs of sense that is crucial to observation, but rather the existence of a distinction. As Spencer-Brown puts it, ‘we take as given the idea of distinction and the idea of indication, and that we cannot make an indication without drawing a distinction’.18 Indication is the act of observation, while distinction is what renders the observation possible. Alternatively, we could say that distinction is the transcendental condition or condition for the possibility of indications or observations.

Spencer-Brown contends that ‘a [world] comes into being when a space is severed or taken apart. The skin of a living organism cuts off an outside from an inside. So does the circumference of a circle in a plane.’19 Each of these worlds has its own immanent logic, a logic of visibility and invisibility arising from the distinctions that have been drawn, rendering observation possible. Here it is crucial to note that the distinctions drawn are contingent or capable of being drawn otherwise. As Spencer-Brown puts it, ‘the boundaries can be drawn anywhere [the observer] pleases’.20 Different worlds will come into visibility as a result.21 In a phenomenological register we could refer to observation as ‘phenomenality’ or ‘givenness’, while distinction would be that which gives the given. My thesis is that Luhmann’s theory of distinction allows us to articulate a common frame or logic belonging to a wide variety of different correlationisms. However, as we shall see, Luhmann’s theory of distinction, despite his own intentions, also allows us to critique correlationism.

Spencer-Brown represents the distinction that renders observation possible with the following symbol:

Figure 1

That which falls under the bracket is what can be indicated as a result of drawing the distinction. However, it is important to note that the distinction has two sides, which are referred to as the marked and unmarked spaces of the distinction.

Figure 2

The two sides of the distinction – the marked and unmarked space – taken together are referred to as a ‘form’. To reiterate: the observer just is the distinction – not an organism or organs – whether that observer be an animal, human, social system or computer technology. Already we see a posthuman twist in Luhmann’s theory of distinction, for a wide variety of entities can deploy distinctions and be observers.

Spencer-Brown’s point is that to observe or indicate anything at all a distinction must be drawn that excludes or places other beings, events, lines of thought, etc., in an unmarked space. Being or the universe as such cannot be indicated; or rather, the attempt to observe the universe as such would present only pure chaos. Thus, for example, when zoology observes horses there is a prior distinction that renders this indication possible – a distinction that delineates horses – and there is necessarily an exclusion of everything else that is not indicated by this distinction. In this context, it is crucial to note that it is zoology (not the scientist) that is the observer. In other words, there is a social system, a discursive system, that draws the distinction allowing horses to be observed. The distinction is itself contingent, such that it could be drawn differently. For example, while zoology might draw distinctions so as to indicate shared biological features among different species of equines, the discursive system of the preindustrial American military cavalry might have drawn distinctions to indicate the suitability of horses for war. These different distinctions cause very different things to appear.

The real value of Spencer-Brown’s theory of observation lies not in his account of indication but rather in how it draws attention to what is not indicated. Every form is haunted by two blind spots. There is, of course, the unmarked space of the distinction or that which is excluded from observation. However, more profoundly, what is also unobserved in observation is the observer or the distinction itself. As Luhmann puts it, drawing on Michel Serres, ‘the observer is the nonobservable. The distinction he uses to indicate the one side or the other [of the form] serves as the invisible condition of seeing, as blind spot.’22 It is as if distinction, in allowing something to appear, creates a sort of optical illusion where that which appears is encountered as identical to that which is rather than being an effect of the distinction (observer) that brings it into relief. As a consequence, Luhmann will constantly remind us that the observer ‘cannot see what it cannot see’, and that ‘reality is what one does not perceive when one perceives it’.23 If we cannot see what we cannot see, then this is because the distinction that constitutes the indication withdraws in the act of being used. By contrast, if we do not perceive reality when we perceive it, then this is because the distinction only exists for the system that observes reality and does not exist in the environment of the system without the act of observation. Thus Luhmann will remark elsewhere that for the system drawing the distinction, ‘the world as it is and the world as it is being observed cannot be distinguished’.24

Far from merely presenting an account of how indication or observation takes place, Luhmann’s theory of observation invites us to engage in second-order observation or to ‘observe the observer’. While an observer is not able to observe itself as operating with distinctions to make indications, another observation (deploying a new distinction) or observer can observe the first observer to discern both how the observed observer draws its distinctions and what its blind spots are. Investigating the distinctions that constitute and produce givenness for these systems is what takes place in second-order observation. Of course, in observing the observer a new distinction will be drawn with its own blind spots: one can operate with distinctions by making indications, or observe distinctions, but cannot do both at once:

All observation (including the observing of observations) presupposes the operative deployment of a distinction that at the moment of its use must be employed ‘blindly’ (in the sense of ‘non-observably’). If one wants to observe the distinction in its turn, one has to employ a different distinction for which the same is true.25

For example, the United States cavalry can either indicate horses suitable for war or observe the criteria it has formulated (distinctions) to indicate war-horses, but it cannot do both at once. If it indicates war-horses, the distinction it uses to make that observation becomes invisible; while if it observes those distinctions, war-horses become invisible. The distinction that renders the observation possible always goes unobserved, even as it functions as the condition for the observation. For the cavalry, horses just are what its distinctions have predelineated.

Here, then, the value of Spencer-Brown’s and Luhmann’s theory of observation becomes apparent. As Luhmann remarks, observation ‘can claim no extrawordly, privileged standpoint’.26 Furthermore, there is not an observer but observers – as many observers as there are distinctions. As a consequence, second-order observation ‘destroys [the] “one observer – one nature – one world” assumption’ characteristic of philosophy.27 No longer can we presuppose the existence of a universal cogito as in the case of Descartes, nor a transcendental unity of apperception as in the case of Kant, nor a transcendental ego as in the case of Husserl. In each case, these universal – or monotonously first-order – observers function to ground a shared and identical world. However, second-order observation reveals that there are as many observers as there are distinctions and that these observers need not at all be human (and on this basis the assumption that all humans draw distinctions in the same way or that there is even a universal set of features shared by all humans is highly questionable). Other animals, social systems and artificial intelligences are also observers.

Luhmann thus argues that second-order observation presents us with a theory in which there is no distinct reality out there,28 and that therefore second-order systems theory brings about a deontologization of reality.29 They do so because, as we saw earlier, systems cannot distinguish the world as it is and the world as it is observed. Luhmann will go even further and remark that ‘there are no correlates in the environment of [a] system … even for distinctions and designations’.30 As he continues, ‘all distinctions and designations are purely internal recursive operations of a system’.31 I hope to show in a moment why this is a questionable thesis, but for now it is sufficient to point out that if Luhmann is right, if it is the case that it is distinctions that allow beings to come forth and that distinctions do not exist in the environment of a system – and therefore that the entities that come forth do not exist in the environment of systems – then we can no longer speak of a reality out there apart from systems of observation. There is only that which presents itself to systems as a consequence of the distinctions deployed by that system; and because there are many different distinctions there will be many different realities.

Luhmann’s twist to Kant’s correlationist revolution consists in undermining the universality of the structure of correlation, showing how the drawing of distinctions is capable of producing a variety of different structures of phenomenality or givenness. It is here that we encounter his poststructuralist dimension. Luhmann doesn’t hesitate to characterize deconstruction as second-order observation or the activity of showing how distinctions produce different worlds or fields of phenomenality.32 In works like The Order of Things, Foucault can be thought as demonstrating the manner in which various systems of knowledge discursively produce their objects in different ways at different points in history through the distinctions they deploy.33 The uncanny effect of Foucault’s archaeologies lies in revealing the contingency of these systems of knowledge, or how they are contingent and lack a one-to-one correspondence with reality. Judith Butler does something similar with gender, showing how gender is discursively and performatively produced through the deployment of a contingent set of distinctions. In the case of Jacques Lacan it has shown how the fundamental fantasy functions as a frame or set of distinctions for the unconscious subject, structuring its relation to the Other and reality. While it would be a mistake to characterize Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari as correlationists, they do, following Jakob von Uexküll, develop a posthuman correlationism that explores the world of nonhuman organisms through a second-order observation of how these organisms observe that they call ‘ethology’.34 In addition to providing a formal framework for comprehending commonalities among these diverse thinkers through his formal theory of observation, Luhmann also contributes to the poststructuralist framework by developing a posthumanist account of how systems themselves are observers deploying their own distinctions (e.g. economic, political, religious and other systems) independent of humans. With qualifications when it comes to Deleuze and Guattari, and the later work of Foucault, each of these thinkers can be thought as engaging in a form of reflexive or second-order observation that reveals the contingency of a set of distinctions and their accompanying objects while also investigating the blind spots that haunt these systems.

Observing correlationism: Why realism and materialism now?

Correlationism invites us to engage in second-order observation of systems, of how these systems observe, revealing: (a) the contingency of the distinctions they deploy in the production of phenomena, the ‘given’, or objects; (b) the blind spots of these systems; (c) the reality-effect these systems produce; and, finally, (d) that these systems have no direct relationship to reality. In doing so, the second-order observation or correlationism common to poststructuralism presents a compelling critique of representationalist realist accounts of truth wherein systems conform to a reality that exists independent of that system.

Given the persuasiveness of poststructuralist correlationism’s critique (hereafter PSC), we might ask why we are witnessing a resurgence of realism? Why has realism not been safely buried and become a curious relic of intellectual history? It is likely that there is no single answer to this question. However, much of the resurgence of realism probably has to do with the material circumstances within which we find ourselves today: in our current circumstances the environment has increasingly forced itself to the attention of observing systems in ways that are not easily susceptible to correlationist or constructivist analysis. This intrusion of the environment into observing systems has taken place first and foremost with respect to climate change. However, it has also arisen from the new technologies that have transformed both the face of the globe and how we live, as well as the centrality of energy in sustaining our social systems. In all of these instances we must think a form of causal agency that doesn’t result from distinctions, but from the physical or material properties of entities themselves independent of whatever distinctions a system happens to draw.

To see why PSC has difficulty handling these sorts of material agencies we can engage in a second-order observation of correlationism itself, asking both what correlationism observes and what its blind spots are. Paradoxically, it is Luhmann’s theory of observation, which purports to deontologize reality, that allows us to critique PSC. With notable exceptions, such as Deleuze and Guattari and the later Foucault, it would not be amiss to say that PSCs predominantly observe meaning, signs, signification, narrative and discourses, demonstrating how entities and identities are effects of the distinctions drawn by these agencies. As Lacan formulates the thesis, ‘there’s no such thing as a prediscursive reality. Every reality is founded and defined by a discourse’.35 More dramatically yet, he remarks that ‘[t]he universe is the flower of rhetoric’.36 Within this framework, reality, then, is an effect of discourse or rhetoric. In his own work, Luhmann will argue that reality is an effect of communication. Yet climate change and the powers of technology are not effects of discourse, signs, signifiers or communication, but rather result from powers that belong to material entities themselves.

As a consequence of this thesis, it is discourse in some form or another that falls in the marked space of poststructuralist, correlationist thought. The referent of discourse and that which is outside of discourse but that does not appear in discourse falls into the unmarked space of PSC. While poststructuralism, as a variant of correlationism, claims to think the relation between system and object, it in fact reduces the object to signification. As Stacy Alaimo puts it, ‘[m]atter, the vast stuff of the world and of ourselves, has been subdivided into manageable “bits” or flattened into a “blank slate” for human inscription’.37 Materials, entities, are treated as blank slates that are carriers of human inscriptions or embodied forms of rhetoric. As a result, the object becomes a text to be deciphered and interpreted like a novel or film. One of the clearest examples of this would be Baudrillard’s System of Objects, where we are shown how commodities embody unconscious meanings that reinforce everything from class divisions to patriarchy;38 but also Slavoj Žižek’s The Plague of Fantasies, where we are presented with an analysis of French, German and English toilets, showing how each embodies a different national ideology (German reflective thoroughness, French revolutionary haste and English utilitarian pragmatism).39

While it seems to be the object that is indicated under PSC, it is in fact rather signification or discourse that comes to the fore. The blind spot of PSC is therefore materiality, things, or what Bruno Latour calls ‘actants’. Matters or things introduce differences into the world not by virtue of how they signify within a discourse but by virtue of what they are and the powers or capacities that they possess.40 Carbon emissions do not raise temperatures leading to the melting of polar ice because of signification but by virtue of how they prevent heat from escaping the atmosphere. Likewise, smart phones do not link people globally allowing for coordinated action across the world by virtue of the signifier but because of a system of radio towers, satellites, data bases and so on allowing for linkage via the internet. These are material differences, not signifying differences.

There is, to use Jane Bennett’s language, a force of things, a productive power of things, which does not arise from signification but which is a feature of these things themselves.41 Yet this power of things is precisely what becomes invisible under PSC because this formation of thought deploys a distinction that calls us to not investigate what powers things possess, but rather how they are carriers of meaning that systems have constituted. In observing the blind spot of PSC we are able to shift attention away from signification so as to draw attention to this power of things by virtue of what they are. In other words, through a second-order observation of PSC we cross its line of distinction and enter its unmarked space so as to observe from the standpoint of materiality. Furthermore, it is not merely that PSC prevents us from discerning the power of matters necessary for understanding things such as climate change, it is also that discursive power is not the only form that power takes. As Latour has so persuasively shown, for example, power is not simply exercised discursively but also nondiscursively through the agency of things and how they afford and constrain various social relations.42 While it is indeed the case that systems of signification exercise all sorts of power by virtue of how they sort, categorize and define us, material features of environments exercise power in all sorts of subtle and dramatic ways as well. Here we might think of different suburban home designs. To be sure, the architecture of homes reflects signifying assumptions regarding families, relations between men and women, relations between parents and children, the activities with which people occupy themselves, etc. However, power here is not exercised merely at the level of signification, but rather also involves physical features of the home. For example, a kitchen that is separated from the general living and dining area exercises a power of segregation from partners and children not merely by virtue of signification but by virtue of plaster, stone, sheet rock and wood that creates real physical separations between those who dwell in the home. It is not the signifier alone that exercises power, but also these material agencies. Indeed, as Foucault taught us in his discussion of the panopticon, the material features of architecture can exercise a power of its own independent of signification. A home, in its material being, could be thought as a sort of machine that separates and relates living bodies – let’s not forget animals that dwell in homes – both within the home through walls and hallways, as well as with respect to the outside world through openings, doors, and windows. These material channels and walls play a key role in how living bodies relate, yet all of this becomes invisible if we attend to signification alone.

Observing machines

It would be a mistake to abandon PSC for it has shown us, in a compelling way, how the identities we take as having being in their own right are, in fact, contingent constructions of social relations functioning as supports for unjust power. In demonstrating this, PSC opens a space for emancipatory politics; for where identities are constructions rather than natural beings it becomes possible to construct different identities and to contest systems of categorization that organize social relations and segregate living bodies. However, we have also seen that things exercise a power of their own, independent of signification, and that certain things such as climate change or the role that infrastructure, geography and technology play simply cannot be properly understood as long as we remain within the theoretical framework of PSC. These things require a realist framework that does justice to the power and agency of things. Although I cannot address the epistemological complexities of the issue here – in this context I advance my argument on pragmatic grounds – what is needed is some way of distinguishing those elements that are constituted by systems such that they do not exist in the environment of the system in which they appear from those that have independent existence in their own right.43

What is needed is, then, a framework powerful enough to capture both of these orientations without abandoning the gains of poststructuralist critique nor reducing things to carriers of signification and products of systems. While I can only sketch an outline of such an account here, it turns out that Luhmann’s thought ironically contributes many elements to such a theory. If such a move is surprising, then this is because Luhmann was so insistent in claiming that his thought deontologized reality and spelled the ruin of any notion of independent reality. Here everything spins on reading Luhmann against himself and in raising the question of whether he can coherently maintain the position he claims to defend. In other words, we must ask whether Luhmann’s thought does not harbour hidden realist resources that, in a sort of Aufhebung, allow us to both retain the contributions of PSC while also imagining a new form of realist thought.

We have already seen how Luhmann’s theory of distinctions and observation can be turned against itself to observe the blind spots of PSC, thereby paving the way to an observation of the contributions of material beings. However, it is also worth noting that Luhmann’s own thought, despite its avowed rejection of ontology, is itself dependent on a variety of ontological theses.44 As he remarks in Social Systems, ‘it is crucial to distinguish between the environment of a system and systems in the environment of this system’.45 That is, Luhmann’s sociological project of observing social systems cannot get off the ground without positing the existence of systems. Systems do not merely constitute beings through the distinctions they deploy, they are beings. Yet if we grant the existence of systems independent of other systems, why should we not grant the existence of other beings that are not of the order of observing systems but independent of them?

While I cannot here go into all the details of his complicated theory of systems, Luhmann draws a distinction between the environment that systems constitute and systems that exist independent of a system. Luhmann argues that ‘the point of departure for all systems-theoretical analysis must be the difference between system and environment’.46 His thesis is that systems constitute themselves by distinguishing themselves from an environment, but also that they constitute their environment. As he remarks, ‘the environment receives its unity through the system and only in relation to the system’.47 In other words, there is not one environment, but as many different environments as there are systems. The point here is quite simple: take the bee as an example of a system; bees constitute their environment and give it a unity in the sense that they are only selectively open to their environment in terms of what they can sense and what they attend to as relevant to their existence (flowers, the hive, other bees, certain predators, and so on). Luhmann contends that ‘elements are elements only for the system that employs them as units and they are such only through this system’.48 For example, for the bee, flowers are not flowers but sources of nectar. Similarly, what interests the capitalist is not the commodity as a physical object but only what it is as a unit in exchange. The biology of trees only interests capitalism insofar as it affects that system of exchange and otherwise falls into the unmarked space of capitalism. It is in this sense that systems constitute their own elements. Nonetheless, there are also other systems that exist in the environment of a system that may or may not belong to the environment the system constitutes. In the environment of the bee there are all sorts of microorganisms that do not belong to the bee’s environment; and leaves exist in the environment of the lumber market but are not elements in that system of exchange.

It is clear from the foregoing that a sleight of hand is at work in Luhmann’s thought, for he uses the term ‘environment’ in two quite different senses. On the one hand, there is the environment that systems constitute as a set of selections from the chaos of the world that are relevant to its ongoing operations. Let us abbreviate this environment as Ec to denote the constituted environment that the system observes through its distinctions. On the other hand, there is the environment that exists independent of the system regardless of whether the system observes it. We can call this environment Ei to denote the independently existing environment. Luhmann remarks that the constitution of Ec always involves risk in that

establishing and maintaining the difference between system and environment … becomes the problem, because for each system the environment is more complex than the system itself. Systems lack the ‘requisite variety’ … that would enable them to react to every state of the environment … There is … no point-for-point correspondence between system and environment.49

Clearly, when Luhmann refers to risk and an environment more complex than the system he is referring to Ei rather than Ec; an environment more complex than a system is one that is not registered by that system. Because of the constraints of time or acting on the one hand, and the overwhelming complexity of Ei on the other, the system is forced to select in constituting Ec. This selection involves risk, since that which it ignores in selecting might ultimately spell the demise of the system. For example, in failing to monitor asteroids in our solar system we risk the destruction of the earth due to a catastrophic impact, but one cannot monitor everything in real time and still operate.

We thus see that Luhmann’s position compels him to adopt a tempered form of realism along three fronts. First, Luhmann must posit the existence of other systems for his sociological project of observing systems to be coherent. These other systems can’t merely be constituted by the observing system if his sociology is to be informative. Other systems must themselves exist as entities independent of the system that observes them. We might have a distorted understanding of these systems as a result of our own distinctions but that doesn’t undermine their existence. Second, he must posit the existence of an environment external to a system (Ei) independent of the environment that the system constitutes (Ec) to account for what might be called the ‘perspectivism’ of systems theory and his account of risk, selection and complexity. Third, building on his commitment to systems theory, while systems might constitute their own elements, these elements cannot be constituted ex nihilo. They must draw on some sort of matter that is then formed as an element of the system. For example, an organism as a system constitutes its cells as elements of its own system, but it must draw on all sorts of materials to do this. Likewise, social systems must draw on all sorts of materials to constitute their elements (identities, roles, hierarchies, communications, etc.). Indeed, as Luhmann’s thought develops, we find that he increasingly discusses material phenomena such as writing and communications technologies that are not strictly of the order of observing systems constituting their own objects or elements, but which nonetheless play a key role in how social systems evolve and develop.50 These technologies contribute to the evolution of society not by virtue of what they communicate but by virtue of how they allow communications take place. As McLuhan famously put it, here ‘the medium is the message’.51

To be clear, the aim here is not one of abandoning Luhmann and PSC so as to defend a naive realism, but rather one of creating a space in which the resources of PSC can be preserved. While he is not often associated with the poststructuralists, it is my view that Luhmann provides the most sophisticated and, due to its formalism, the most integrative theory of PSC available – and it also allows us to think the contributions of materiality to social assemblages. Luhmann’s theory of systems and observation allows us to see how systems constitute fields of selective relevance (Ec), characteristic of how a system constitutes its elements, while also providing the means to think environments independent of systems (Ei) that nonetheless contribute to the form social assemblages take. Where many strains of PSC tended towards a sort of imperialism of language, signification or the outside, Luhmann’s systems theory shows the limits of constitution in Ecs, allowing us to think an outside while also giving us the means to explore the variety of ways in which systems constitute their environments and subject these constitutions to emancipatory critique.

Notes

1.There is a great deal of confusion surrounding the term ‘object-oriented ontology’ (OOO), treating it as synonymous with the ontology proposed by Graham Harman. I coined the term ‘object-oriented ontology’ in July 2009 to distinguish ontologies committed to the existence of substances, entities or objects from Harman’s specific ontology and its commitments, or ‘object-oriented philosophy’ (OOP); see Graham Harman, ‘Series Editor’s Preface’, in Levi R. Bryant, Onto-Cartography: An Ontology of Machines and Media (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014), p. ix. OOO is thus a genus term like ‘rationalism’, ‘empiricism’, ‘idealism’, ‘materialism’ or ‘poststructuralism’. It refers not to a unified ontology, but to a variety of different ontologies committed to the thesis that being is composed of substances. While these thinkers might not themselves accept the label, examples of object-oriented ontologies would be Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, Leibniz, Whitehead, Deleuze (under one reading), Bruno Latour, Isabella Stengers, Jane Bennett, Stacy Alaimo, etc. Clearly there are heated debates among these thinkers regarding just what constitutes a substance, just as there were debates among the reationalists, among the empiricists, and among the idealists. While often sympathetic, my onticology and machine-oriented ontology, developed elsewhere in The Democracy of Objects (Ann Arbor: Open Humanities Press, 2011) and Onto-Cartography, are proposed as materialist and Deleuzian alternatives to Graham Harman’s ontology of nonrelationality, vicarious causation and withdrawal.

2.See Ian Hacking, The Social Construction of What? (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000). Such positions argue that there are some features of entities that are intrinsic, while there are others that only exist for an observer.

3.Personal correspondence with Graham Harman in 2010.

4.Graham Harman has been a vocal critic of materialism. As a consequence, it should be noted that while all materialisms are necessarily realisms, not all realisms are materialisms.

5.Quentin Meillassoux, After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency, trans. Ray Brassier (New York: Continuum, 2008), p. 5.

6.Ibid.

7.Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, trans. Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), Bxvi.

8.Ibid., A111.

9.Ibid., B148.

10.In the world of philosophy and theory, it is not uncommon for one to find an exception to a generalization and triumphantly declare that the generalization is ill-founded. For example, Gilles Deleuze certainly does not fit the model of correlationism, nor, as Harman has argued, does Latour easily fit this model; see his Prince of Networks: Bruno Latour and Metaphysics (Melbourne: re.press, 2009). Harman, of course, shares the thesis that correlationism or philosophies of access dominate Continental thought. The issue here is not whether or not exceptions exist – they always do – but rather what view dominates within a discursive community. Within the discursive community of Continental thought defined by its presses, journals and graduate programmes, correlationist thought certainly defines the majoritarian or prevalent trend of philosophy.

11.Another name for ‘correlationism’ is antirealism. For a brilliant account of how antirealism or correlationism has dominated contemporary Continental philosophy, see Lee Braver, A Thing of This World: A History of Continental Anti-Realism (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2007).

12.Quentin Meillassoux, ‘Presentation by Quentin Meillassoux’, in Robin Mackay and Dustin McWherter, Collapse III: Unknown Deleuze [+ Speculative Realism] (Falmouth: Urbanomic, 2007), p. 409.

13.Karl Marx, Capital: Volume 1, trans. Ben Fowkes (New York: Penguin, 1990), p. 165.

14.Lucretius, The Way Things Are: The De Rerum Natura of Titus Lucretius Carus, trans. Rolfe Humphries (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1968), p. 33.

15.Aristotle, Politics, trans. Benjamin Jowett, in Jonathan Barnes (ed.), The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation: Vol. 2 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), 1254b15–21.

16.For Foucault, see Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1977). For Butler, see Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 2006).

17.See for example Derrida, ‘White Mythology: Metaphor in the Text of Philosophy’, in Margins of Philosophy, trans. Alan Bass (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1986).

18.George Spencer-Brown, Laws of Form (New York: EP Dutton Publishing, 1979), p. 1.

19.Ibid., p. xxix, modified.

20.Ibid., modified.

21.Throughout what follows I distinguish between ‘universe’ and ‘world’. ‘Universe’ denotes what is independent of all distinctions. It would be there regardless of whether or not distinctions were drawn. ‘World’ denotes that which appears as a consequence of a system drawing a distinction.

22.Niklas Luhmann, Theory of Society: Volume 1, trans. Rhodes Barrett (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012), p. 35.

23.Niklas Luhmann, ‘The Cognitive Program of Constructivism and the Reality that Remains Unknown’, trans. Peter Germain et al., in William Rasch (ed.), Theories of Distinction: Redescribing Descriptions of Modernity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002), pp. 129, 141.

24.Niklas Luhmann, The Reality of the Mass Media, trans. Kathleen Cross (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000), p. 11.

25.Luhmann, ‘Constructivism’, p. 135.

26.Luhmann, ‘Identity – What or How?’, in Distinction, p. 114.

27.Luhmann, ‘Deconstruction as Second-Order Observing’, in Distinction, p. 96.

28.Ibid., p. 108.

29.Luhmann, ‘The Program of Constructivism’, p. 132.

30.Ibid., p. 135.

31.Ibid.

32.Luhmann, ‘Deconstruction’.

33.Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences, trans. uncredited (New York: Vintage Books, 1994).

34.Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), pp. 256–65.

35.Jacques Lacan, Encore: On Feminine Sexuality, The Limits of Love and Knowledge, 1972–1973, trans. Bruce Fink (New York: W. W. Norton, 1998), p. 32.

36.Ibid., p. 56.

37.Stacy Alaimo, Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), p. 1.

38.Jean Baudrillard, System of Objects, trans. James Benedict (New York: Verso, 2005).

39.Slavoj Žižek, The Plague of Fantasies (New York: Verso, 1997), pp. 4–5.

40.While I cannot develop it in detail here, elsewhere I argue that entities are defined not by their qualities or properties but rather by their powers or capacities; see especially Bryant, Democracy, chapter four, and Onto-Cartography, pp. 40–6. In this, I follow Spinoza’s account of affect as well as the ontology developed by George Molnar.

41.Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010).

42.See, for example, Bruno Latour, Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies, trans. Catherine Porter (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999).

43.In Democracy, chapter two, I draw on Roy Bhaskar’s earlier work to develop a transcendental argument showing that experience and inquiry can only be coherently understood if the world (not mind, as Kant would have it) is a certain way and that entities independent of mind exist.

44.See Luhmann ‘Identity’ for his critique of ontology, which is a constant throughout all of his work.

45.Niklas Luhmann, Social Systems, trans. John Bednarz Jr. and Dirk Baecker (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995), p. 17.

46.Ibid., p. 16.

47.Ibid., p. 17.

48.Ibid., p. 22.

49.Ibid., p. 25.

50.Luhmann, Theory of Society, §§2.5–2.8.

51.Marshall and Eric McLuhan, Laws of Media: The New Science (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988), p. 5.