M

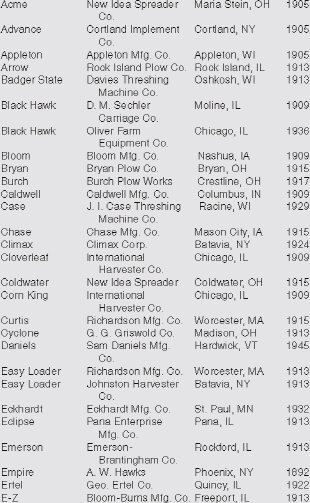

Manure Spreaders

Only a few patents were issued for manure spreaders prior to 1875. Of these, none gained any importance. Subsequently, Joseph S. Kemp designed a spreader while residing at Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. His original 1875 design marked the beginning of a practical and successful manure spreader. By 1904, Kemp had accumulated nearly 15 different patents on manure spreaders, the first one coming in 1877.

Farmers were well aware of manure’s value as a soil conditioner and fertilizer. Numerous agriculturists editorialized on the subject and several books were written on the subject. Despite this, the pre-spreader days saw an unpleasant task for every farmer, since the only alternative was to pile it up in the yard. When manure spreaders first came to the forefront in the 1880s, they were a welcome sight; by 1910 the majority of farms across the United States owned a manure spreader. Considering the number of farms at the time, there was a tremendous demand and manufacturers abounded. After market saturation, one after another left this business for another or perhaps abandoned business aspirations altogether.

Today, manure spreaders bear little resemblance to those early designs, yet the underlying purpose remains the same—fertilize the soil with animal manure. Occasionally, the term “fertilizer distributor” was used in the early days, but most farmers and most manufacturers called it what it was—a manure spreader.

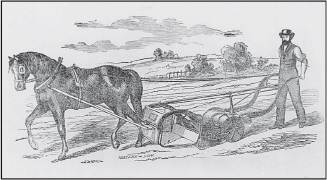

Before the invention of the manure spreader, farmers loaded barnyard manure onto a wagon, then drove to the field and scattered it by hand. Leaving large clumps wouldn’t work; later on it would plug up the plow. This is what it was like in the “good ol’ days.”

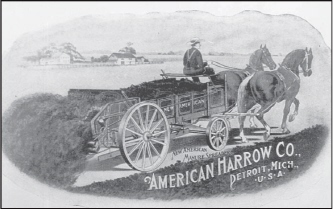

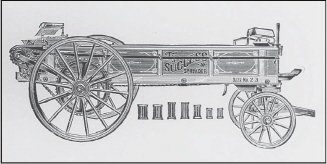

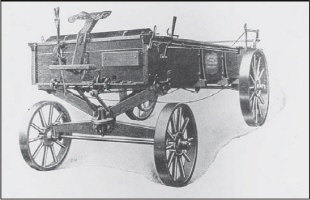

American Harrow Co., Detroit, Mich.

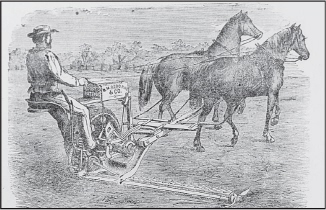

For 1905, this was the appearance of the New American manure spreader from American Harrow Co. It was typical of the time, using what was essentially a heavy wagon chassis to which was fitted the spreader box and mechanism.

American Seeding Machine Co., Springfield, Ohio

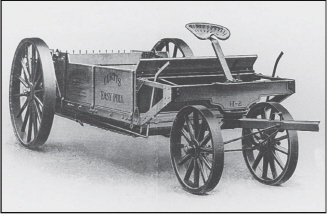

D.M. Sechler Carriage Co., Moline, Ill., developed the Black Hawk manure spreader in the early 1900s. Eventually, this firm went out of business, apparently being acquired by American Seeding Machine Co. The latter offered several styles in subsequent years, this one being the New Black Hawk No. 40A of 1927.

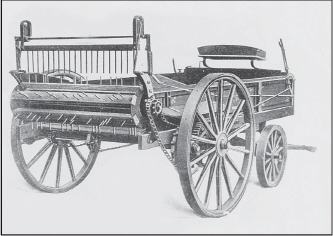

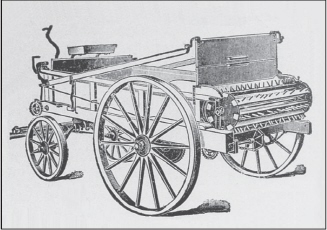

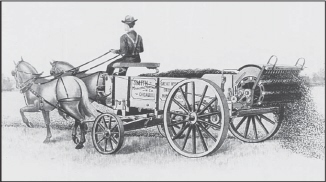

Appleton Manufacturing Co., Batavia, Ill.

Appleton offered this style of manure spreader in 1906. It was a heavy wooden design, but offered cut-under front wheels to permit the short turns required to back into a barn or shed for ease in loading. By 1906, the market was booming in the manure spreader business.

A radical departure from the high-profile spreader designs of earlier times was this low-down style offered by Appleton in 1917. Appleton began building spreaders in 1905 and this machine of 12 years later shows marked improvement, including the use of a steel frame.

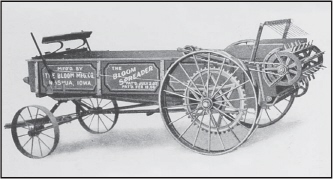

Bloom Manufacturing Co., Nashua, Iowa

Two sizes of Bloom spreaders were available in 1910—the 65-bushel model and the larger 75-bushel spreader. Bloom’s spreader evidenced the trend to a low-profile design; farmers disliked pitching manure by hand into a spreader nearly as tall as they were. Bloom apparently began building spreaders about 1906. Eventually, the company relocated to Independence, Iowa.

Cedar Rapids Implement Works, Cedar Rapids, Iowa

In 1906, the Up-2-Date Manure Spreader appeared from this firm; it was billed as being the most modern spreader of the time. This one, like many others, used a returnable apron instead of the continuous apron design. The latter was not held in high esteem at the time, but has since come to be the universal method of delivering material to the beaters. This operation lasted but a few years.

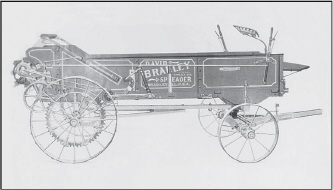

David Bradley Manufacturing Co., Bradley, Ill.

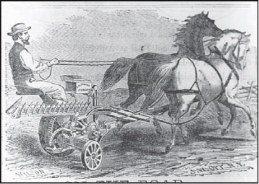

From about 1910 comes this illustration of the David Bradley Manure Spreader, which it claimed was the “strongest, simplest and most perfect working spreader made.” An attractive feature of this lightweight spreader was that it carried a price of only $69.50.

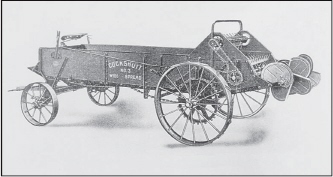

Cockshutt Plow Co. Ltd., Brantford, Ontario

About 1914, the Cockshutt No. 3 Manure Spreader appeared; this one was fitted with Hyatt roller bearings for easier draft and longer life. This spreader typified the low-profile design to follow at least into the 1930s. It was simple and, best of all, it was low to the ground.

Cortland Implement Co., Cortland, N.Y.

A 1905 advertisement illustrates the Improved Advance spreader with an endless apron design. For the Midwest, J.I. Case Plow Works at Racine, Wis., functioned as agents and this likely improved the sales base considerably. Little is known of this company.

Deere & Co., Moline, Ill.

An important design development was embodied in the John Deere manure spreader of 1924. As pictured here, the main beater was mounted directly over the drive axle. This permitted a low profile while providing beater teeth exactly where they were needed. Deere manure spreaders are also illustrated in the color section of this book.

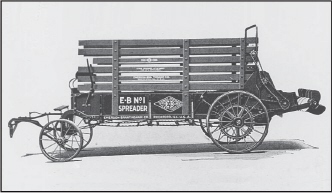

Emerson-Brantingham Co., Rockford, Ill.

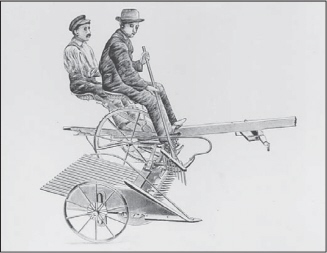

Emerson-Brantingham built several sizes and styles of manure spreaders. Its 1919 offering included this one-man straw-spreader attachment. This device was primarily for hauling the remainder of a straw stack back to the field in spring to be used as fertilizer. The straw attachment is attached to the E-B No. 1 spreader.

A.B. Farquhar Co. Ltd., York, Pa.

In the 1930s, Farquhar offered its Non-Wrap spreader. This referred to the beater design, intended to minimize wrapping of long straw around the beater blades. Farquhar spreaders were sold primarily in the Eastern states and were not as well known in the Midwest.

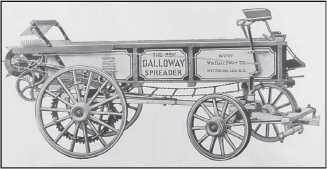

Wm. Galloway Co., Waterloo, Iowa

By 1912, the Galloway catalog was going to thousands of farmers and included items like this Wagon Box Spreader. For about $50, a farmer could buy one of these spreaders, attaching it to his own running gear and instantly having a manure spreader. This design was fairly popular, especially since the same running gear could be used for other purposes. Within a few years this style lost out to dedicated designs.

Galloway’s catalog mail-order business included almost everything for the farm, including the 80-bushel Jumbo spreader, shown in its 1914 catalog. At the time, this was a huge spreader, particularly when most designs ranged from 50 to 65 bushels. This spreader retailed for $93.50.

Glen Wagon Co., Seneca Falls, N.Y.

The Johnson Star Manure Spreader is shown here from a 1909 advertisement. This model was sold through numerous jobbing houses, including Dain Manufacturing Co., Parlin & Orendorff, plus several others in the Midwest. However, nothing is known of the company or the spreader, aside from this advertisement.

Independent Harvester Co., Plano, Ill.

By the time this 1917 promotion appeared, most companies had developed a low-profile design for its spreaders. For the Independent, this was achieved by using narrowed front wheels and a cut-under design to permit sharp turns, as when backing into a barn or shed.

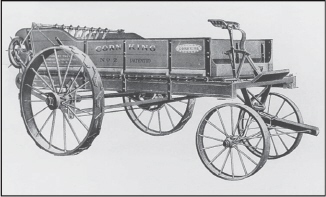

International Harvester Co., Chicago, Ill.

Almost from its 1902 beginning, IHC sold Kemp spreaders through its dealer organization. Harvester bought the Kemp factory at Newark Valley, N.Y., in 1906, along with certain of the Kemp patents. In addition, Harvester leased the company’s factory at Waterloo, Iowa, until 1908, but did not renew the lease after that time. Shown here is the IHC Corn King Spreader No. 2 of 1905.

A 1905 offering from IHC was its Cloverleaf Spreader No. 2. It was much like the competing Corn King model; one style was sold by Deering dealers and the other by McCormick dealers. Operating several different companies under a single corporate umbrella created many problems, including some interesting clashes between dealers in the same town.

By 1920, the IHC manure spreader line included the International roller-bearing model with an auto-steer front axle, a tight bottom and a wide-spread attachment. Few farm machines saved as much labor for the farmer as did the manure spreader. While the tractor-mounted manure loader didn’t become a practical reality until the 1930s and later, pitching the manure onto the spreader wasn’t the worst job on the farm and was certainly better than having to pitch the same load off by hand once in the field.

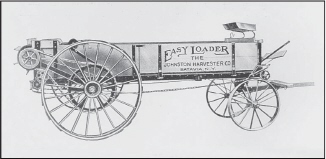

Johnston Harvester Co., Batavia, N.Y.

In 1913, Johnston bought out the Richardson Manufacturing Co., of Worcester, Mass. The latter had been building the Worcester-Kemp spreaders for some years, with Johnston buying its spreaders from Richardson until the 1913 takeover. Subsequently, Johnston began manufacturing the “Easy Loader” spreaders at its own plant in Batavia. Johnston sold out to Massey-Harris in 1917.

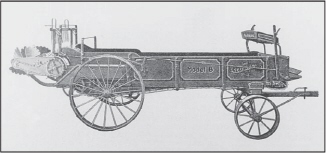

J.S. Kemp Manufacturing Co., Newark Valley, N.Y.

In 1875, Joseph Kemp built the first successful manure spreader. At the time, Kemp was working in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. This first machine carried about 25 bushels and was made at a cost of about $300. From this first design came a host of manufacturers looking for a share of the market by 1900.

By the beginning of 1900, Kemp had introduced its 20th Century manure spreaders. At this point, Kemp had already enlisted numerous branch houses and agents to distribute the new machine and set up a branch office at Cedar Rapids, Iowa. By the time this 1903 advertisement appeared, Kemp was selling spreaders to International Harvester Co.

In the early 1900s, Kemp set up a Midwestern factory at Waterloo, Iowa. IHC leased this factory for two years commencing in 1906 and ending in 1908. Subsequently, Kemp announced its new Kemp’s Triumph spreader, a front-unloading design. Also known as The Federal Spreader Works, this 1908 company advertised heavily for a time that year; after that, no further trace has been found.

Kemp & Burpee Manufacturing Co., Syracuse, N.Y., apparently was operating in the early 1900s or perhaps before; meanwhile, the Newark Valley, N.Y., factory was also viable. By the 1920s, parts for the Original Kemp spreaders were available from Deere & Co.

Litchfield Manufacturing Co., Waterloo, Iowa

Litchfield began manufacturing manure spreaders in the early 1900s, apparently continuing in this business approximately until World War II. This design of about 1915 was quite popular with Midwestern farmers and bore a striking resemblance to other low-down designs of the period. The company also made various other farm implements.

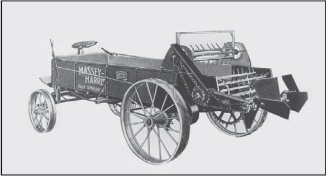

Massey-Harris Harvester Co., Batavia, N.Y.

With the 1917 purchase of Johnston Harvester Co., Massey-Harris acquired a fully developed line of manure spreaders. The 1920s included this No. 7 model, a modern looking outfit with a wide spread attachment. During the 1920s and 1930s, manure spreaders changed little, but, with the coming of small row crop tractors, farmers were soon looking for power-driven tractor manure spreaders.

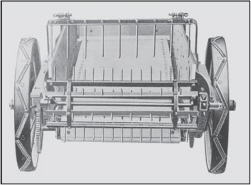

Geo. B. Miller & Son Manufacturing Co., Waterloo, Iowa

Numerous farm equipment manufacturers have been located at Waterloo, Iowa. One of these, Geo. B. Miller & Son, manufactured many items of farm equipment, electing to build the Robinson spreaders for a time in the 1920s. Shown here is the Robinson straight-beater design; the endless wooden apron is also evident.

To provide a wide-spread feature to the ordinary beater, the Robinson angle beater was used. This one used a rather complicated set of castings with interlocking teeth at the center. They permitted the beater to tear the straw apart at the rear of the machine, all the while casting it out in a wide pattern. The Robinson design came from the Robinson Spreader Co. noted below.

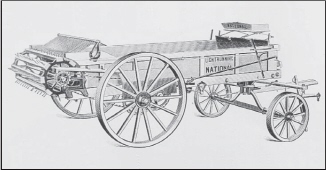

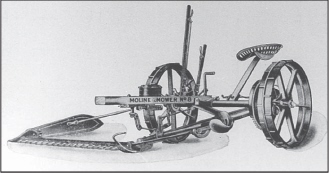

Moline Plow Co., Moline, Ill.

In 1906, Moline Plow Co. announced its National Light Running Manure Spreader. This one was built at the company’s Mandt Wagon Co., in Stoughton, Wis. In a promotional piece, Moline gave more than 20 reasons why farmers should select its spreader above all others. A later style of the Moline spreader is pictured in the color section of this book.

New Idea Spreader Co., Maria Stein, Ohio

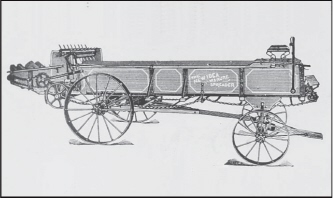

For 1905, New Idea offered their Acme Manure Spreader. At this time the company was situated at Maria Stein, Ohio, but later relocated to nearby Coldwater, Ohio.

Of all manure spreader manufacturers, New Idea was one of the most prolific, building numerous models and sizes over a long career in the business. Shown here is its original New Idea design; this spreader was built in the 1904-09 period.

In the 1909-12 period, New Idea offered this new design; it had a 75-bushel capacity and also included a wide-spread attachment. In fact, New Idea claimed to be the original design with a wide-spread attachment.

By 1922, the New Idea line included this improved style, with a noticeably different wide-spread attachment. The latter would change but little for some years to come. The New Idea B-3 was a continuation of the Model B spreader of the 1912-14 period.

New Idea sold its spreaders under the NISCO trademark for a number of years, with this one being the New NISCO Model 6 of 1926. A New Idea parts book notes that this one was “painted red with black lettering.”

In 1927, New Idea emerged with its No. 8 spreader; it had a 70-bushel capacity. Roller bearings were extensively used, along with 7-inch rear drive wheels. Company parts books note that this spreader “is painted a dark orange with green trimmings.”

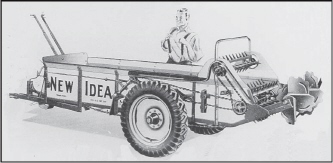

By 1940, New Idea was offering the farmer a new Model 12 tractor drawn spreader. This was a ground-driven model that gained tremendous popularity and enjoyed a long production run.

Newark Machine Co., Newark, Ohio

A 1908 advertisement noted that this spreader was “the result of twenty-five years of experience.” That would mean that the Miller spreader from Newark Machine Co., saw first light in 1883. Little else is known of the company aside from this illustration.

Ohio Cultivator Co., Bellevue, Ohio

Ohio Cultivator Co. apparently did not begin manufacturing its own manure spreaders until the early 1920s. However, the Ohio spreaders became fairly popular within a short time, partially due to the company’s reputation with various other farm implements. In 1935, the company announced its new Famous Ohio spreader, an improved version with many of the modern features found on spreaders of its time.

Oliver Farm Equipment Co., Chicago, Ill.

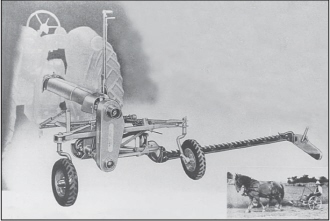

In 1939, the Oliver Superior manure spreader line was augmented with the tractor spreader (in the bottom part of the illustration). It was a second choice over the conventional horse-drawn model shown at the top. The Oliver spreader line had the Superior spreader from American Seeding Machine Co. as its direct ancestor. The latter was one of the partners in the 1929 merger forming Oliver Farm Equipment Co.

Racine-Sattley Co., Kansas City, Kan.

For reasons now unknown, this spreader was manufactured by Racine-Sattley Co., of Kansas rather than at the main plant in Springfield, Ill. Another curiosity is that this Up-to-Date manure spreader reappears at Cedar Rapids Implement Co., a couple of years later. Further details are unknown.

Richardson Manufacturing Co., Worcester, Mass.

In 1903, Richardson Manufacturing Co. advertised this Worcester Kemp manure spreader; it was built under license of certain Kemp patents. Numerous jobbing houses handled the Worcester Kemp spreader, including several in the Midwestern states. Eventually, the line was bought out by Johnston Harvester Co., Batavia, N.Y.

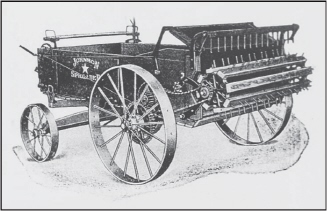

Robinson Spreader Co., Vinton, Iowa

Apparently, beginning about 1906, Robinson offered this spreader to the farmer. The unique feature was a wide-spread beater unlike any other. Various claims were made for this design and the company continued building these spreaders for several years. Eventually, the Robinson factory closed, with Geo. B. Miller & Sons at Waterloo, Iowa, taking up the design and putting it on the market for a few more years.

Rock Island Plow Co., Rock Island, Ill.

Rock Island Plow Co., introduced the Model B spreader shown here in 1922. This design was fairly popular, although it continued to use a stiff front axle at a time when many companies were opting for the auto-steer front axle. The latter eventually became the norm, since it permitted sharp turns that were impossible for the design shown here. Rock Island began selling the Great Western spreaders from Smith Manufacturing Co. in 1911.

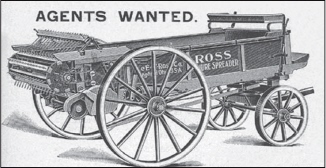

E. W. Ross Company, Springfield, Ohio

E. W. Ross had developed a sizable implement line by 1905, especially with ensilage cutters and feed cutters. The Ross Manure Spreader of the time was offered in 50, 70, and 100-bushel sizes. The largest model was indeed big. Few companies offered anything more than a 70-bushel size.

Rude Bros. Manufacturing Co., Liberty, Ind.

A product of the 1920s was this Rude manure spreader. As noted elsewhere, Rude had a long history in the farm equipment business, finally opting to concentrate all its efforts on manufacturing manure spreaders. Sometime in the 1930s, Rude became a part of General Implement Co.; in the 1940s, repair parts could be secured from B.F. Avery Co.

Did You Know?

A corn binder in good condition will fetch in excess of $200 today.

D.M. Sechler Carriage Co., Moline, Ill.

For 1906, the Black Hawk spreader from D.M. Sechler Carriage Co. took the same essential form as the Kemp spreaders of the same period. More than likely the design was built under license from Kemp. Sechler continued to build the Black Hawk for a number of years; eventually, parts for the Black Hawk could be secured from Oliver Farm Equipment Co.

Smith Manufacturing Co., Chicago, Ill.

By 1905, the farm implement line from Smith Manufacturing Co. was well known and was also very extensive. Its Great Western line included an endless apron manure spreader by 1905 and this continued for some years. In 1911, Smith made an agreement with Rock Island Plow Co. for the latter to handle its spreaders. Eventually, Rock Island came into control of the Great Western line.

Standard Harrow Co., Utica, N.Y.

Another of many early spreaders using the Kemp designs was the Standard shown in its 1904 edition. Farmers were anxious to buy manure spreaders because they saved a tremendous amount of work. Besides, taking another load to the field gave an opportunity for rest before pitching on another load.

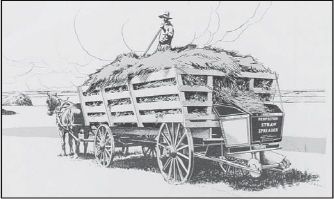

Union Foundry & Machine Co., Ottawa, Kan.

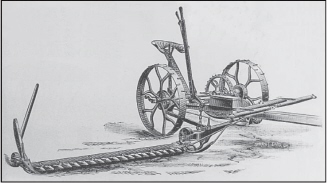

In some areas, particularly the wheat-growing regions, there was always far more straw than could be used. Thus came the Perfection Straw Spreader in 1915. This $75 outfit attached to the rear of a hay rack, providing the means to evenly spread unused straw over the fields. The company also advertised this device as a manure spreader. But since it had no apron or unloading device, it is unlikely that this application was of any great value.

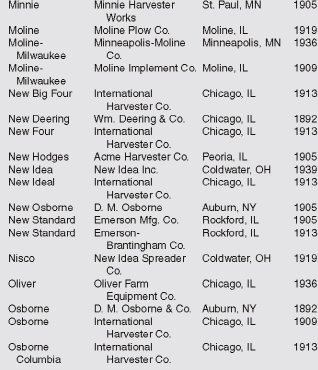

Trade Names

Milking Machines

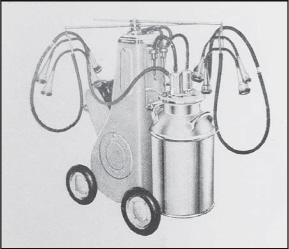

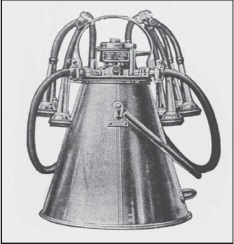

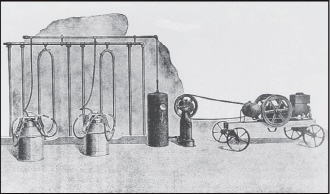

About 1910, the first practical milking machines appeared, but most of the early models remained on the market for a short time, then disappeared. Work continued, however, on milking machine designs; by the 1920s, there were some practical models available. Particularly in the Midwestern states, dairy cows were a part of most farms. Some farmers had half a dozen cows or less, while others might milk 15 or 20 cows by hand, morning and night, every day of the year. Particularly to the latter group, the milking machine came as a great invention.

Conventional milkers, as shown in this section, flourished until the 1950s, when the coming of pipeline milkers and dairy parlors changed the methodology once again. An aside to the milking machines themselves were some of the peculiar devices used for the required vacuum system. Some companies made a specialty of these units, as is noted below. Other companies built milking machines that are not shown here, primarily due to a lack of illustrations for these machines. No particular antique value has been established for vintage milking machines.

Ben H. Anderson Manufacturing Co., Madison, Wis.

Outside of this 1940 advertisement, nothing is known of the Clean Easy Portable Milker. This machine used an ordinary milk can as the storage receptacle, conveying milk directly from the cow to the can. When it was full, the can was hoisted into a large tank of chilled water for immediate cooling.

Babson Bros., Chicago, Ill.

In the late 1920s, the Surge milkers appeared from Babson Bros., at Chicago. With this design a long surcingle was placed over the cow’s back, and the notched handle shown here was hooked into place. This eliminated the long tubes required of other designs. Surge milkers immediately became very popular and the Surge line is still well known among dairymen. This illustration dates to 1927.

D.H. Burrell & Co., Little Falls, N.Y.

A 1910 offering was the Burrell-Lawrence-Kennedy Milking Machine, also known simply as the B-L-K milker. This one first came out in 1908 and remained on the market for several years.

DeLaval Separator Co., New York, N.Y.

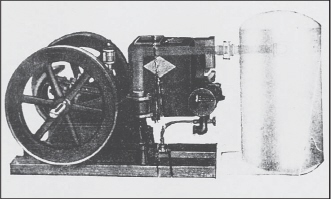

DeLaval pioneered the development of the cream separator and was a leading force in the development of the milking machine. This 1928 illustration shows the Alpha-DeLaval engine to the right; it is belted to the vacuum-pump system. Two milkers are in place, with the farmer moving to another cow in the interim. Milking machines greatly lessened the time required for this twice-daily process.

Empire Cream Separator Co., Bloomfield, N.J.

About 1917, Empire began offering milking machines to the farmer; the company had already made a name for itself with its cream separators. The Empire line proved to be quite popular, so much so, that in 1925, Rock Island Plow Co., took on the Empire milker line, offering it through its Rock Island implement dealer organization.

Globe Milker Inc., Des Moines, Iowa

In 1941, the Globe portable milker appeared. This design was a completely self-contained unit with its own vacuum pump built into the milker. Probably due to the onset of World War II, it does not appear that the Globe milker was marketed for any length of time, but additional information has not been located.

Liberty Cow Milker Co., Hammond, Ind.

For 1910, Liberty offered its cow-milker direct to the farmer, noting that there were “no jobbers, no catalogue houses and no trusts” to deal with. Aside from this advertisement, nothing more can be found on the company. Up to about 1915, these machines were usually billed as “cow milkers.” The term “milking machine” came into vogue after that time.

Perfection Manufacturing Co., Minneapolis, Minn.

Perfection milkers were well known by dairymen. The company developed this machine sometime before World War I and continued to build milkers for decades. Meanwhile, many other manufacturers entered the market and left again after only a short time in business.

Taylor Engine Co., Elgin, Ill.

By the early 1920s, the Taylor Vacuum engine appeared. This special design included a vacuum piston and cylinder cast in place directly behind the engine piston. Thus, the engine served as a vacuum pump and an engine within a single unit. Various other engine-vacuum pump combinations were built, but none compared to the Taylor design.

Waterloo Gasoline Engine Co., Waterloo, Iowa

In 1916, this company announced its Waterloo Boy Milker. To the right is the vacuum pump and storage tank. Belted to the pump is a Waterloo Boy gasoline engine; to the left are two milker units. Deere & Co., bought out Waterloo Gasoline Engine Co., in 1918, but nothing regarding the Waterloo Boy milker has been found in its literature.

Trade Names

Trade Names

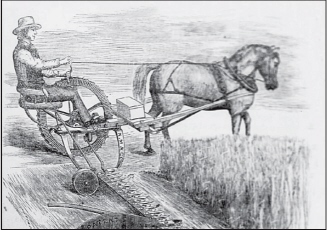

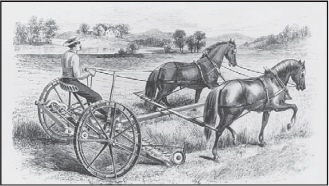

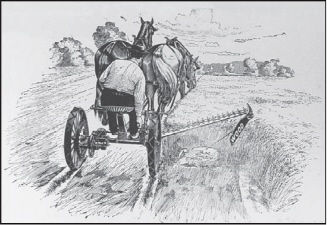

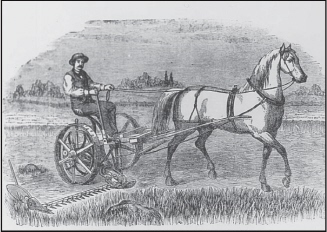

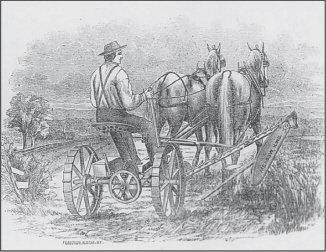

Mowers

When first developed in the 1850s, mowers were also known as mowing machines. The latter title stuck for 20 years or so, but eventually everyone—manufacturers and farmers alike—opted for the simpler term. “Mower” has been the term ever since.

In the author’s 150 Years of International Harvester (Crestline/Motorbooks: 1981), an outline is presented regarding the complex tangle of patents, infringement suits and the pandemonium created by a host of mower patents held or licensed by a host of manufacturers. Complicating matters further, some reapers were built as double-purpose machines, being a reaper or a mower. Although the idea didn’t work very well, it still was better than having neither machine and resorting to hand methods once again.

This section illustrates many different mowers built at various stages of their development, being the products of many different manufacturers. Of those shown, many others were built but for which no illustrations were available as the book was assembled. Complicating the matter further, the same mower was sometimes built simultaneously by two or more companies.

Among collectors of vintage farm equipment, old mowing machines have acquired a market value that is quite variable. Very old machines often bring $250 or more, even in poor condition. Later machines, usually after 1920, can sometimes sell for $100 or more, but many of these can be bought for much less, especially those that have resided outdoors for half a century or more.

Acme Harvester Co., Peoria, Ill.

This 1899 advertisement for the Hodges Mower lists the company as Acme Harvesting Machine Co., Pekin, Ill. By 1903, Acme was listed at Peoria and building the New Hodges Mower, an improved design. Little of the history concerning Acme can presently be found.

Did You Know?

Disc harrows are generally not a highly prized item; restored and repainted examples, however, might bring $200 to $300.

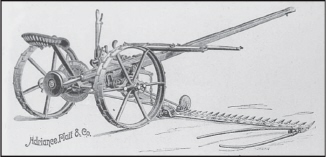

Adriance, Platt & Co., Poughkeepsie, N.Y.

An 1895 advertisement illustrates the Adriance Buckeye Mower which they termed as being The Original Buckeye. Adriance, Platt & Co. had a long career in the mower business, but this ended when the company was bought out by Moline Plow Co. in 1912.

Aetna Manufacturing Co., Salem, Ohio

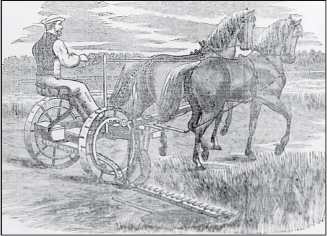

For 1869, Aetna offered its Mower and Reaper, built under the Amos Rank patents. Particularly during the 1860s and 1870s, mower patents abounded, with many of them overlapping to such a degree that patent suits were commonplace. In this engraving, the Aetna is shown “on the road.” Little history of the firm can now be found.

Ames Plow Co., Boston, Mass.

During the 1850s, Ames Plow Co., emerged as a major Eastern manufacturer of plows and other implements. By the late 1860s, the company was offering the Perry Gold Medal mower as shown. This unusual design placed the mower bar within the center of the right-hand wheel, as shown in the engraving. By 1866, Ames Plow Co. had taken over Nourse & Mason Co. also of Boston; the latter had become well known for building the Kirby mowers.

C. Aultman & Co., Canton, Ohio

For 1868, Aultman offered this style of the Buckeye Mower &Reaper. Through a tangled series of takeovers, buyouts, reorganizations and mergers, Ball, Aultman & Co. appears in the mix, with Lewis Miller as the inventive force. Eventually, Miller came to own most of Ball, Aultman & Co.

By 1878, Aultman & Co. had announced its New Buckeye mower; this hinged-bar design was due to the inventiveness of Lewis Miller. The latter is generally credited with inventing the hinged-bar design; in fact, once the Miller design was marketed, there were so many other “hinged-bar” patents that eventually they were combined in the Hinged Bar Pool so that participating manufacturers could build under license from the pool and avoid the constant tangle of infringement suits.

Aultman, Miller & Co., Akron, Ohio

Extensive research would be required to follow the development of the Buckeye mowers. Aultman, Miller & Co. appeared, apparently by the 1880s, as the successor to Ball, Aultman & Co. Its 1901 catalog illustrates this center-cut mower, a design still on the market, despite some 30 years of hinged-bar machines.

A 1901 Aultman-Miller catalog illustrates its hinged-bar mower of the day. By this time, mowing machines had been well perfected and would give the farmer day after day of trouble-free operation. Subsequently, Aultman, Miller & Co., came under stock control of International Harvester Co., in 1903. In 1905, the implement line was abandoned and the factory was converted to making twine and automobiles.

Koenig mowers appear in a 1907 advertisement, with the copy noting that “The Koenig Mower is an exact duplicate of the old Aultman, Miller & Co. Mower.” This design was offered for sale by Weber Implement Co., St. Louis.

B.F. Avery & Sons, Louisville, Kty.

A 1916 catalog illustration shows the Avery Champion one-horse mower. This machine was made in two sizes—a 3-1/2 and a 4-foot model. This style was billed as being ideal for places where the ordinary two-horse model would be too large. If desired, the thills could be replaced with an ordinary tongue for use with two horses.

Champion Improved Mowers took the form shown here for the 1916 Avery catalog. By this time, most mowers had the same general form, featuring a hinged bar, foot-lift device and cast-iron wheels. The most noticeable differences were in the drive mechanism.

J.I. Case Co., Racine, Wis.

Case introduced its new Oil-Bath Mower in 1934. This model was a major leap forward because the drive gears were now enclosed in an oil-tight case. Aside from this feature, the mower was a continuation of the designs created by Emerson-Branting-ham Co. J.I. Case purchased E-B in 1928.

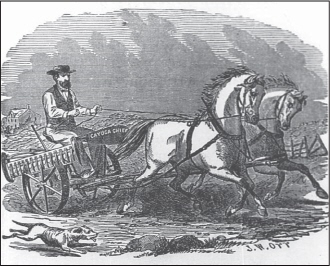

Cayuga Chief Manufacturing Co., Auburn, N.Y.

The Cayuga Chief emerged in the 1860s as a leading design from Cyrenus Wheeler Jr. Major conflicts existed between Wheeler’s patents and those of several others, especially Lewis Miller. Eventually, the contentions subsided; in 1874, the Cayuga Chief came under ownership of D.M. Osborne Co., also in Auburn.

Clipper Mower & Reaper Co., Yonkers, N.Y.

An engraving of 1870 shows the one-horse Clipper at work. This machine used a 3-1/2 foot cutter bar and weighed but 480 pounds. Clipper first marketed this machine in 1866, building 50 units that year. Two years later, the company made 580 machines, but could not fulfill all of its orders. Little else is known of the company outside of this illustration and accompanying data.

Corry Machine Co., Corry, Pa.

Outside of an 1869 engraving, nothing is known of the Climax Mower from Corry Machine Co. Numerous manufacturers built mowers for a time, particularly during the 1860s and 1870s. Usually these were built under license from another company or perhaps from the Hinged Bar Pool, a patent pool that operated for several years, ending in 1871.

Dain Manufacturing Co., Ottumwa, Iowa

Dain’s early manufacturing efforts centered on haying equipment. This included the Dain Center-Draft Mower shown here in its 1894 version. Little is known of this early Dain design; in fact, when this mower was built, Dain was still operating his factory in Missouri. The company was founded in 1881 and came under control of Deere & Co., in 1911.

Deere & Co., marketed much of the Dain equipment line prior to gaining stock control of the Dain operation in 1911. A 1908 John Deere Plow Co. catalog illustrates the Dain Vertical Lift Mower; this model was made in 5- and 6-foot sizes.

Deere & Co., Moline, Ill.

In 1927, Deere offered this High-Lift Mower as part of its haying machine arsenal. The Deere mowers were direct descendants of the Dain mower, pioneered in the 1890s and sold by Deere for some years until a final takeover in 1911.

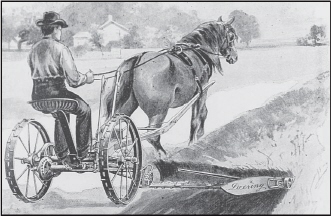

Deering Harvester Co., Chicago, Ill.

For 1885, Deering offered mowers in several styles, including the Deering Ideal Giant, its largest model. At this point in time, the principles of mower design were well established and Deering had a factory capable of building a top quality machine. In addition, Deer-ing had already developed an extensive dealer organization.

Deering Ideal one-horse mowers for 1899 were offered in 3-1/ 2 and 4-foot sizes. This small mower was ideal for the small farmer and indeed, the “Ideal” trade name lent further credence to an excellent design.

By 1899, Deering had further developed the Ideal and Ideal Giant mowers of the 1880s, with these mowers continuing into the 1902 merger that formed International Harvester Co. Deering mowers continued in the IHC line into the 1920s.

Emerson-Brantingham Co., Rockford, Ill.

The Emerson line of mowers went back to the 1850s with the Manny reapers. Subsequently, the company built and sold numerous styles of mowing machines. This New Standard mower is of 1907 vintage. Essentially the same mower was built by Emerson-Brantingham until the company sold out to J.I. Case in 1928.

In 1919, Emerson-Brantingham acquired D.M. Osborne & Co. from International Harvester. Subsequently, the company offered E-B Osborne mowers in many styles and sizes. Shown here is its 1919 version of the No. 2 mower, a small model made in a 4-1/2 and a 5-foot cut.

An unusual mower for 1919 was this E-B Standard 8-foot mower. While most horse mowers were of 5- or 6-foot design, a few were made in 7-foot sizes. Rare indeed was the 8-foot model, since most farmers considered it to be too heavy for a team, especially considering the side draft.

Frost & Wood Manufacturing Co. Ltd., Smiths Falls, Ontario

A 1910 offering of Frost & Wood was the Giant Mower. This Canadian company built several styles of mowers at the time, but little history of the firm has been located, aside from its 1910 catalog.

R.L. Howard, Buffalo, N.Y.

Sometime prior to 1860, R.L. Howard Co. acquired the interests of the Ketchum mower. The Ketchum design was one of the earliest successful mowing machines and Howard continued building it for some years; the style shown here graced the cover of its 1860 catalog. Eventually, Howard slips from view and no further information has been located.

Hussey Mower & Implement Co., Knightstown, Ind.

A 1903 advertisement illustrates the Hussey No-Pitman Mower. This rather complicated design was intended to obviate the need for the usual mower pitman which sometimes caused problems. However, the advantages were probably offset by the complicated mechanism of the design. Aside from this 1903 illustration, nothing further is known of the company.

International Harvester Co., Chicago, Ill.

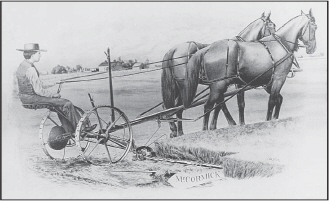

A 1920 catalog lists the McCormick No. 6 mower. This was essentially the same McCormick mower that the company had been building for years. By this time, McCormick mowers had been shipped all over the world, in addition to being a household term in the United States.

Deering mowers of 1920 were little different than those the company brought into the 1902 merger forming International Harvester Co. From the McCormick and the Deering designs, the company came out in the 1920s with a McCormick-Deering design that embodied all the best from both designs.

Johnston Harvester Co., Batavia, N.Y.

Johnston Harvester had roots going back to the 1840s, with the firm operating under the title of Johnston, Huntley & Co. for some years. During the 1860s, Johnston-Huntley sold its patented Cycloid mower as pictured here. Its success led to the subsequent development of improved designs.

Johnston’s Wrought Iron Mower made its appearance in the 1870s. This design was unusual in its placement of the cutter bar; the latter pivoted in line with the main axle and was supported by offset bars extending from the machine frame.

By the 1890s, Johnston had developed an entirely new line of mowers and harvesting equipment under its Continental trade name. Shown here is the Continental Mower No. 6 of 1892. This machine featured a variable speed drive so that it could easily be adapted to various mowing conditions.

Johnston Harvester Co., came under stock control of Massey-Harris about 1910, with the latter acquiring the company outright in 1917. During the early 1900s, Johnston continued marketing new mower designs, with this one being known as the Johnston No. 10 Lever-Fold Mower.

McCormick Harvesting Machine Co., Chicago, Ill.

McCormick began building mowers in the 1860s, using its past experience in the reaper business to develop a unique and practical mower. In the years that followed, the McCormick remained a popular design, having developed to the style shown here for 1896.

One of the popular McCormick models was this No. 4 Steel Mower. Billed by McCormick as “the acknowledged king of grass cutters,” the No. 4 embodied great strength and durability. With the extensive McCormick dealer organization, farmers also found it easy to secure repair parts when needed.

Massey-Harris Harvester Co., Batavia, N.Y.

With stock control of Johnston Harvester Co. in 1910, Massey-Harris broadened its sales base considerably. Massey-Harris was based at Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and the usual problems of shipping across national borders prompted the firm to expand with a factory in the United States. With this accomplished, the company bought out Johnston in 1917, continuing to market mowers such as this Massey-Harris No. 20 model.

During the 1930s, many companies recognized the coming of tractor power to all phases of farming. Thus the company developed its No. 5 Semi-Mounted mower strictly for tractor use. Many other companies developed tractor mowers during the 1930s, bringing an end to horse-drawn mowers by the early 1950s.

Milwaukee Harvester Co., Milwaukee, Wisc.

Milwaukee Harvester Co. was a partner of the 1902 merger forming International Harvester Co. The roots of this company went back to the 1850s, with the Milwaukee Harvester name appearing first in 1884. Subsequent to the IHC merger, much of the Milwaukee line was phased out, with its factories being devoted to other manufacturing activities.

Moline Plow Co., Moline, Ill.

Moline Plow Co. made its first major entry into the mower business with its 1912 purchase of Adriance, Platt & Co., Pough-keepsie, N.Y. Subsequently, Moline built on this prior experience and marketed mowers of its own design, including the Moline No. 8 of 1919 vintage; it is shown here.

North River Agricultural Works, New York, N.Y.

An 1866 catalog from North River Agricultural Works illustrates Swift’s Improved Lawn Mower, an interesting machine pulled by one horse and guided by hand. Decades have turned into centuries, so no other information has been located.

Nourse, Mason & Co., Boston, Mass.

The Davis Improved Mowing Machine was built under the Ketchum patents and marketed in this form for 1861. In 1866, the company came under control of Ames Plow Co., but subsequent developments have eluded the current research.

D.M. Osborne & Co., Auburn, N.Y.

For 1866, Osborne offered Kirby’s American Harvester shown here as a mower; this machine was convertible to a reaper. Os-borne was an active participant in the development of the mowing machine and garnered a great many significant patents.

An 1869 pamphlet displays the Kirby mower in the transport position. This was a combination machine designed as a mower, a reaper and a self-raker. Changing from one machine to another was accomplished with relative ease, but the majority of farmers preferred dedicated machines that could mow or reap or rake, but not all in the same unit.

Osborne operated on its own until coming under control of International Harvester Co., about 1903, and coming to a close in 1905. Curiously, IHC continued to sell numerous items of the Osborne line for some years and under the Osborne trademark. Shown here is an Osborne Columbia mower of 1900.

Plano Manufacturing Co., Plano, Ill.

Founded in 1881, Plano was offering the Jones Chain-Drive Mower shortly afterwards; it took the form shown here in 1889. The chain drive was simple and eliminated the need for noisy and troublesome gears, but it also had its disadvantages. A chain is no stronger than its weakest link and weak chain links certainly were cause for a farmer to have extras on hand.

A 1900 advertisement in the American Agriculturist shows the Jones mower at that time; it differs very little from its 1889 edition. Subsequently, the Plano line was merged into International Harvester when the latter was organized in 1902.

Sandwich Manufacturing Co., Sandwich, Ill.

This company, formed in 1867, was a well-known manufacturer of corn shellers. Several members of the Adams Family were involved in the company, among them being J. Phelps Adams, who devised a hinged-bar mower somewhat similar to that of Lewis Miller (see Aultman, Miller & Co. listing). In the 1880s, the Sandwich Chain Geared Mower appeared; it continued on the market for several years. The 1890 model is pictured here.

Seiberling & Miller Co., Doylestown, Ohio

An illustration of about 1900 shows the No. 3 Standard Senior Mower from Seiberling & Miller. It is equipped with a hand-operated dropper. With the dropper teeth raised as shown, hay or grain accumulated until the operator tripped the hand lever to leave behind gavels of grain suitable for hand binding. Little else is known of the company aside from this illustration.

James A. Smith & Co., Ancaster, Ontario

Wheeler’s Combined Reaper & Mower is illustrated in this 1874 engraving. Obviously, it was being built under patents owned or controlled by Cyrenus Wheeler Jr. The latter was a major force in the American development of the mowing machine. The mower is shown here in its transport position.

Sprague Mowing Machine Co., Providence, R.I.

From 1872 comes this illustration of the Sprague mower. William Sprague was its president and had been involved in the design of mowing machines for some years. This model uses a hinged-bar design; the gearing is enclosed in a huge cast-iron case to keep out dust and dirt. With occasional oiling, gears and bearings in these early machines lasted far longer than might have been expected.

Syracuse Agricultural Works, Syracuse, N.Y.

An advertisement of the 1880s illustrates the new Hubbard mower from Syracuse Agricultural Works. Moses G. Hubbard was responsible for at least four different patents on mowing machines; in fact, when McCormick Harvesting Machine Co., entered the arena, its first mowers were built under license from Hubbard.

Warder, Bushnell & Glessner Co., Springfield, Ohio

Warder, Brokaw & Child at Springfield, Ohio included a sheet of instructions for its Champion Mowing Machine of 1855. Farmers were warned to “Follow the Directions or No Warranty.” This early design preceded the hinged-bar mowers; the machine shown here had the cutter bar attached rigidly to the frame.

An 1892 advertisement displays the Whiteley’s Champion mower of the time; this was a hinged bar machine that included all the latest developments of the Champion line. Ten years later, the Champion line would become a part of International Harvester Co.

Warrior Mower Co., Little Falls, N.Y.

From the June 6, 1874, issue of Boston Cultivator comes this engraving of the Warrior mower, a hinged-bar machine typical of its day. It is shown here with the farmer raising the lever to dodge a large stone. The Warrior was undoubtedly built under license from one or more patentees, but no further information on the firm has been located.

Wilber, Stevens & Co., Poughkeepsie, N.Y.

An advertisement of the 1880s shows this company’s Eureka mower at work in the field. This was a center-cut design and, unlike most of these machines, the Eureka employed an unusual hitch that placed the horses outside of the cutting area.

No promotion would have been complete without this demonstration of the Eureka on the road. Since the farmer’s coattails are flying, one gets the impression of a substantial road speed. J.D. Wilber acquired several mower patents in the 1860s and 1870s.

Walter A. Wood Mowing & Reaping Machine Co.,Hoosick Falls, N.Y.

From 1887, this engraving illustrates the Wood Mowing Attachment as used on the company’s reapers. Numerous companies offered these conversion units for a multiple-use or combination machine. Apparently, they met a mediocre reception, partially because of the work required to convert the machines back and forth for varying duties.

Organized already in the 1850s, the Wood operations continued under Walter A. Wood’s leadership, until his death in 1892. The Wood design was the first to feature enclosed gearing; this was a distinct advantage in prolonging the life of the machine. Shown here is a Walter A. Wood mower of 1887.

In the 1890s, Walter A. Wood announced its new Tubular Steel Mower. This new design did away with much of the cast iron formerly used and simultaneously provided great strength. By the 1920s, repair parts for these mowers were still available from the company; this, too, came to an end about 1930.

Wm. Anson Wood, Albany, N.Y.

Current research has not determined the connection, if one existed, between this company and Walter A. Wood’s Co., Hoosick Falls, N.Y. For 1878, William Anson Wood advertised the Eagle mower as shown here. Beyond the illustration, no further information can be located.

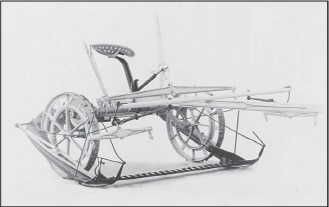

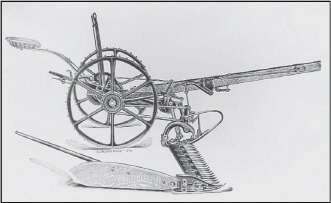

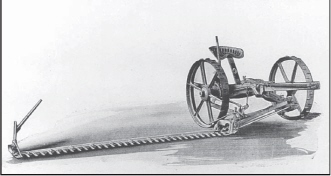

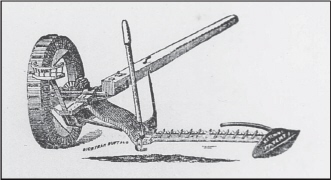

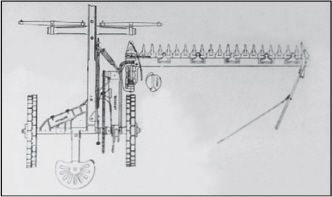

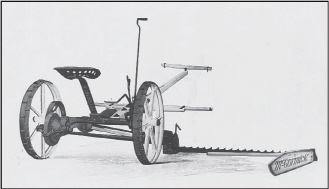

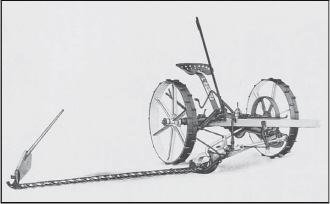

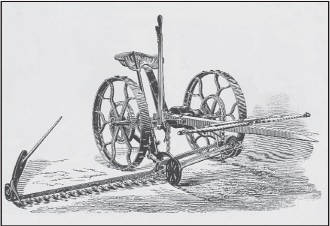

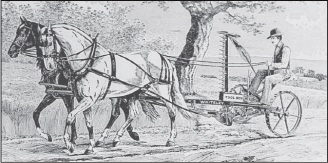

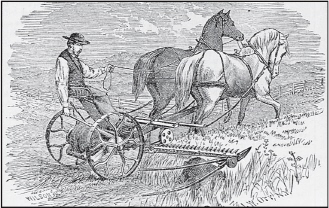

Miscellany

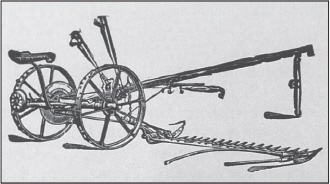

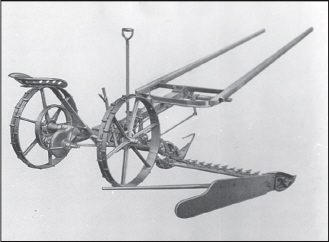

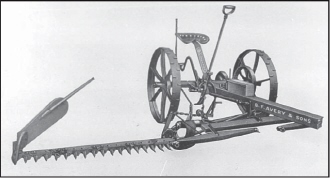

During more than a quarter century of research, the author has acquired many unidentified illustrations, with a few of them being pictured here. All of these machines display interesting designs and perhaps further research will determine the names of their respective manufacturers.

One-horse Kniffen, priced at $110.

Meadow King mower.

Granite Mowing Machine of 1866.

An 1884 engraving illustrates the Improved Seven-Foot Cut Smith Mower.

Trade Names

Did You Know?

A fanning mill will have a reasonable market value; it is not uncommon for a good machine to bring $100 or much more. Quite often, they are purchased for farm use, rather than as a farm antique.