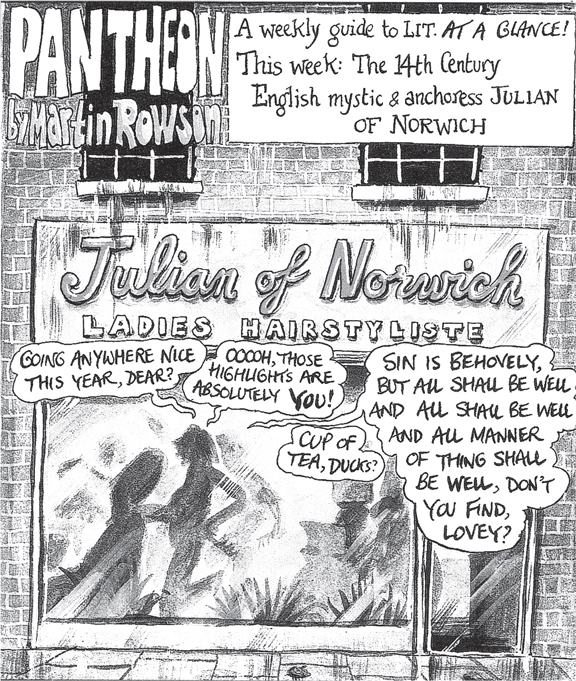

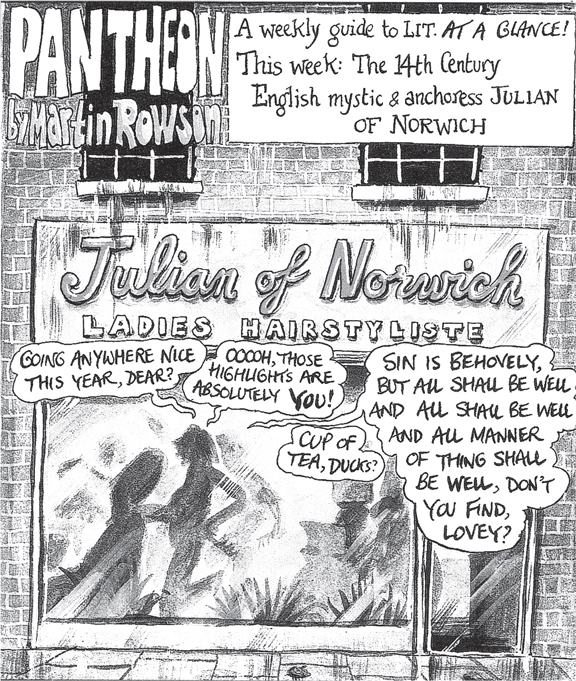

Plate 2. ‘Pantheon: Julian of Norwich’, a cartoon by Martin Rowson, Independent on Sunday, 8 March 1998, by kind permission of the artist.

SARAH SALIH

Julian of Norwich has never been completely forgotten. Alexandra Barratt’s textual history of A Revelation shows that:

Julian’s texts have had a more robustly continuous life than those of any other Middle English mystic. Their history – in manuscript and print, in editions more or less approximating Middle English and in translations more or less approaching Modern English – is virtually unbroken since the fifteenth century.1

Academic interest in her has increased rapidly since the mid twentieth century, and she is now a fixture in the academic canons of the Middle English mystics, of medieval women writers and of vernacular theologians. However, and almost alone amongst such figures, she has a present-day public profile beyond the academy of professional medievalists and theologians. Julian, in fact, currently enjoys what medievalists will recognise as a cult. Like a medieval cult, it adapts and supplements its core materials, in this case A Revelation, in order to construct a figure who can address changing circumstances. Julian has a cult centre at the reconstructed cell in St Julian’s Church, Norwich; she is the patron of the monastic Order of Julian of Norwich, based in Wisconsin; she is iconographically identifiable as a wimpled figure with a cat or hazelnut. Devotional objects and souvenirs, the modern-day equivalents of pilgrim badges, can be bought in worship centres, Christian bookshops and, increasingly, online. The word is spread by a proliferation of texts: as well as numerous editions, translations, abbreviations and selections of the Revelation, there are devotional commentaries, meditations and plays.2 Her words have been set to music and inserted into liturgies.3 Beyond committed Christian circles, she is known as a minor tourist attraction in her home town of Norwich, and via her presence, sometimes in disguise, in novels, poems and at least one film. Though almost all accounts of Julian are constructed from the basic elements of her texts, her anchoritism and something of the late medieval urban environment, the emphases vary, producing, amongst others, feminist Julians, conservative Julians and eco-Julians.

Most are grounded, however, in a consensual selection of the major points of interest in Julian’s writing. Almost all depictions cite her envisioning of all creation in a ‘little thing the quantity of an heselnot, lying in the palme of my hand’ (Vision, 5.7–8),4 and her assertion that ‘Jhesu Crist, that doth good against evil, is oure very moder’ (Revelation, 59.7). The most widely quoted passages are those which show her confidence in God’s love and in ultimate salvation: ‘love was his mening’ (Revelation, 86.14); ‘Thou shalt not be overcome’ (Revelation, 68.54) and, in the phrase which has come to stand for the totality of her thought, ‘alle shalle be wele’ (Revelation, 27.10).

The impact of the hazelnut vision has been greatly intensified since the mid twentieth century by its likeness to the quintessentially modern image of the world seen from space.5 It thus apparently testifies to the timeless truth of Julian’s vision and to the validity of ecological concerns. Kenneth Leech uses the image to call for an earth-based ‘hazelnut theology’.6 In imaginative responses to Julian’s text, the hazelnut’s ecological resonance contributes to its function as a synecdoche – and something of a reification – of mysticism itself. Denise Levertov, who said that she was drawn to Julian by her images, found in those images the extra-temporal moment of the visionary:

God for a moment in our history

placed in that five-fingered

human nest

the macrocosmic egg, sublime paradox

brown hazelnut of All that Is –

made, and belov’d, and preserved.

As still, waking each day within

our microcosm, we find it, and ourselves.7

As Nicholas Watson and Jacqueline Jenkins note, writers’ responses to the hazelnut often take the form of an identification with the visionary.8 Levertov’s dialogue with Julian imitates Julian’s dialogue with Christ; her text encloses Julian’s by incorporating italicized quotations from A Revelation. The conflation of egg and nut, here representing moments of Julian’s childhood and her maturity, make the image encompass all time, in the lifecycle contracted to an egg, as well as all matter. Levertov’s egg/nut also recalls Hildegard of Bingen’s vision of the cosmos as ‘a vast instrument, round and shadowed, in the shape of an egg’, the modern image constructing a thread of feminist-eco-mysticism to link these otherwise quite dissimilar medieval visionaries.9 In the poems of Sarah Law, a former administrator of the Julian Centre in Norwich, the hazelnut is imagined as both the content and the mechanism of another communication across time, space and cultures, between Julian and the Sufi mystic Rumi.10 Iris Murdoch recalls and deliberately twists the scene in her novel, Nuns and Soldiers, in which Christ appears to Anne Cavidge, a former nun who sees herself as a ‘secret anchoress’.11 Though Anne, who has doubtless read Julian, expects a hazelnut, he shows instead a pebble, but its import is the same, and within the novel’s reality the vision is both useful and true:

Still holding hard to the edge of the table, Anne stared at the stone. Then she said slowly, ‘Is it so small?’

‘Yes, Anne.’

‘Everything that is, so little?’

‘Yes.’12

The hazelnut’s ability to signify spiritual knowledge survives the translation of the image into narratives which are otherwise explicitly resistant to its ground in medieval Christian thought. The film Anchoress bases its protagonist on another fourteenth-century English anchoress, Christine Carpenter of Shere, Surrey.13 The historical Christine’s enclosure, unauthorized departure from the anchorhold and re-enclosure are documented, but there is no evidence for her inner life or the form of her piety.14 The film fills this blank space with Julian. In a recurrent shot of Christine holding a round object in the palm of her hand, the film quotes the vision of the hazelnut to signify the authentic, interior spirituality of the young anchoress, contrasted to a Church imagined as repressive, dogmatic and misogynist. The film thus appropriates Julian for an anti-ecclesiastical position, and in doing so produces a reification of mysticism as an unmediated expression of inner spirituality, independent of the devotional practices of its historical moment.

As Frodo Okulam writes, Julian’s exploration of the motherhood of Jesus answers a contemporary desire for ‘positive female images of the divine’.15 The topos has acquired a politics which it did not have in Julian’s day. In the author’s note to Mother Julian and the Gentle Vampire, Jack Pantaleo claims Julian as ‘the world’s first recorded feminist’, and though this novel rehearses various minority responses to Julian, there is indeed a strong feminist element in her present-day fame.16 As Karen Armstrong shows, supporters of women’s ordination cite Julian ‘to prove that the transcendent and ineffable reality of the divine can just as easily be represented by feminine as well as masculine imagery’ and hence that women can perform priestly functions.17 On her controversial election in June 2006 as the first woman leader of the US Episcopal Church, Bishop Katherine Jefferts Schori preached a homily which included the passage:

That bloody cross brings new life into this world. Colossians calls Jesus the firstborn of all creation, the firstborn from the dead. That sweaty, bloody, tear-stained labor of the cross bears new life. Our mother Jesus gives birth to a new creation – and you and I are His children.18

This is a clear echo of Julian’s meditation on a bleeding crucifix and her subsequent articulation of the motherhood of Christ:

oure very moder Jhesu, he alone bereth us to joye and to endlesse leving – blessed mot he be! Thus he sustaineth us within him in love, and traveyled into the full time that he wolde suffer the sharpest throwes. (Revelation, 60.16–18)

Schori’s allusion to Julian is an economical reminder that neither female participation nor feminine images of the divine are new to the Christian churches. That Julian should be cited in preference to the various Christian men who have written on God’s motherhood indicates that she functions as female role model as well as theological authority. However, Christian interest in Julian’s conception of divine maternity does not necessarily translate into support for women’s ordination, or indeed for any other feminist positions. Sheila Upjohn insists that ‘Julian never implies that Christ is female’ in order to allay the ‘alarming thought’ that ‘the militant feminists’ might be right to think of God as a woman.19

Many general readers must first have encountered Julian in the words woven into the meditation of time, timelessness and truth of T. S. Eliot’s ‘Little Gidding’:

And all shall be well and

All manner of thing shall be well

When the tongues of flame are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one.20

As I suggested earlier in this chapter, ‘All shall be well’ is the essential phrase which has come to signify ‘Julian of Norwich’. It captions images of Julian such as the modern window between the reconstructed cell and St Julian’s Church; is regularly highlighted in devotional booklets; appears on prayer cards, bookmarks, mugs and fridge magnets. Quotation of an isolated phrase, however, necessarily obscures the way in which the Revelation tests and worries at the implications of the statement. Christ’s words, ‘Sinne is behovely, but alle shalle be wele, and alle shalle be wele, and alle maner of thinge shalle be wel’ (Revelation, 27.9–11) do not go unchallenged: the questioning Julian persists ‘how might alle be wele?’, ‘methought it was unpossible that alle maner of thing shuld be wele’ (Revelation, 29.2–3; 32.39). Finally accepting the reassurance ‘That that is unpossible to the is not unpossible to me. I shalle save my worde in alle thing, and I shalle make althing wele’ (Revelation, 32.41–2), she nevertheless notes that it is not an answer. It is instead a formula which enables her to accept that the reconciliation of her vision to the teaching of the Church is possible somewhere outside of human understanding. Most sympathetic readers of Julian are at pains to emphasize that the optimism of her salvation theology is hard-won and complex; that it is not, as C. S. Lewis feared it might be, ‘mere drivel’.21 When it is printed in a decorative font on a household object, ‘all shall be well’ tends instead to function as a simpler and less provisional statement: Leech worries that such items mislead readers into ‘pseudo-optimism’.22 Removed from its dialogic context, ‘all shall be well’ seems to be an answer, even the answer, a truth which transcends the historical and textual locations of its articulation. Certainly the phrase has become a cliché, and quotations of ‘all shall be well’ in secular contexts often treat it sceptically or comically. Murdoch, whose fiction is deeply engaged with Julian-like questions about lived ethics, quotes the phrase itself with darkest irony. ‘All shall be well, and all shall be well, as Julian remarked’, says the protagonist of The Black Prince, with utterly unwarranted optimism, for all turns out, for him, very badly indeed.23

Julian the author has been resurrected from her text. Her persona and biography are constructed out of the handful of autobiographical details in A Vision, fewer in A Revelation, her appearance in The Book of Margery Kempe, contextual evidence and a good dose of supposition. The emphasis of this construction tends strongly towards making Julian seem more familiar and contemporary, in line with the often explicitly anti-historicist tenor of her cult: as Michael McLean, then the rector of St Julian’s, put it: ‘We believe that Julian is a woman of our day; that in some mysterious providence of God her wisdom has been “saved up” for our generation.’24

Several writers provide Julian with a history of personal relationships suitable for a woman of our day, using Benedicta Ward’s reconstruction of her biography. Ward argued that the showings occur in a secular household, not a nunnery, and that Julian was therefore more likely to have been, aged thirty, a ‘young widow living in her own household’ than a nun of Carrow priory.25 She tentatively suggests that Julian might have borne and lost at least one child, for which, as she acknowledges, there is no direct evidence. This last hypothesis relies on a circular argument: Julian wrote about motherhood, so we suppose her to have been a mother, which supposition then brings emotional intensity to our reading of her maternal imagery. This narrative appeals intuitively to many commentators: Upjohn, for example, felt Ward’s argument ‘had the ring of truth’.26 Dana Bagshaw’s play Cell Talk and Anya Seton’s novel Katherine, amongst others, take the opportunity of fictionalisation to insert a bereavement into Julian’s biography.27 Ralph Milton’s novel Julian’s Cell develops the theme at perhaps the greatest length to construct a Julian who is distinguished from her contemporaries by her guilt-free enjoyment of marital sexuality.28 Here Julian overcomes her mother’s alarming pre-wedding advice ‘You must lie down on your back and let him do whatever he wants. It will hurt at first. But it is necessary’, to find ‘gentle joy’ in her marriage bed, and rebukes Margery Kempe for her rejection of her husband.29 Milton imagines Julian’s theory of the motherhood of Jesus to be a straightforward transcription of her own experience of mothering:

her reverie sometimes brought a sense of closeness, of a holy presence, and many times she thought God’s nurturing love must be like the mothering love she felt as she fed the child with herself. In those moments she could not imagine anger at the tiny helpless infant in her arms, or imagine how a God who created such a wondrous child could feel anger toward it.30

Julian’s anchoritism provokes a certain unease: a life of virginity, silence and enclosure potentially seems self-indulgent, quietist or just too medieval. As Beelzebub says in Upjohn’s play Mind out of Time, ‘It’s ridiculously easy to discredit a woman, particularly one who probably never married and who spent all her life after the age of thirty in one room.’31 To have been married, then, and preferably a mother too, bolsters a woman’s credibility by establishing her successful achievement of heterosexuality. To suppose Julian to have been a lifelong virgin invites further questions as to whether she was asexual, whether she struggled with sexual temptation, or whether she was lesbian, possibilities which do not recommend themselves to the generally conservative sexual politics of writers on Julian. Upjohn acknowledges that the appeal of the widowhood hypothesis is that it enables her to reject R. H. Thouless’s vulgar-Freudian attribution of ‘suppressed primitive sexual desires’ to Julian.32 The significant exception is Mother Julian and the Gentle Vampire, a novel featuring a reverse-vampire heroine named, unsubtly, Lesbianna, and in which Julian is chastely ‘oned’ with her maid/companion, Lucy.33

Fictive and non-fictive treatments of Julian also accommodate her to modern tastes by reimagining the anchoress as counsellor. Although Ancrene Wisse discourages anchoresses from instructing or showing their learning to their visitors, the Book of Margery Kempe proves that Julian advised at least one person, or at the very least that contemporaries thought it credible that she might have done so.34 The Book also shows, however, that Julian’s reputation was, specifically, for expertise in the discernment of spirits. Margery describes her visions and devotions ‘to wetyn yf þer wer any deceyte in hem, for þe ankres was expert in swech thyngys & gowde cownsel cowd ʒeuyn’, and Julian’s lengthy answer directly addresses her concerns and does not stray from that topic.35 The passage has the dual effect of showing that the orthodoxy of Margery’s visions was confirmed by a qualified specialist and that Julian limited her teaching to one acknowledged area of expertise. Modern retellings, however, often expand Julian’s role into that of a general counsellor or even therapist. Robert Llewelyn suggests that recluses performed the functions of ‘social workers, marriage counsellors, Samaritans, psychiatrists’.36 Brian Thorne calls Julian a ‘radical psychotherapist’ and refers to her ‘work as a counsellor’.37 Thorne’s version of the meeting with Margery articulates his own therapeutic ideal, while departing in many respects from the scene in the Book:

The Julian who listened patiently to the garrulous Margery Kempe who reports the experience in her own writings had no desire to intervene with gratuitous and pious platitudes. She knew that letting Margery talk about herself was a sure way to bring her back to trust in herself and in God as long as she was not impeded by adverse judgements or condemnatory looks.38

This account omits any reference to the established doctrine and practice of discretio spirituum or to the Book’s use of the scene to place both women securely within orthodoxy. The concern of the Book was not Margery’s sense of self but the nature of her visionary experiences, and Julian could hardly have gained a reputation for discernment unless an adverse judgement were a real possibility. Such historically specific concerns, however, would be irrelevant or even counter-productive to the reconstruction of Julian into a figure who meets a more modern need for a patron saint of therapy.

The meeting of Margery and Julian is the main topic of Bagshaw’s play Cell Talk, which elaborates the single recorded encounter into a long-standing relationship of mutual support; of Law’s poem ‘Margery’s Harbour’; and of an icon-painting by Brother Leon of Walsingham, of which postcard reproductions can be bought at the Julian Centre.39 All of these depart from Thorne’s – and indeed the Book’s – model of wise counsellor and humble client by constructing a mutually respectful relation between women whose differences are complementary, rather than oppositional. Law’s poem is particularly noticeable for allowing Margery’s voice, to which she allots a richly concrete string of images of cloth, sea and ships, to tell the meeting. Milton, however, uses the encounter to contrast Julian’s spirituality with Margery’s thoroughly medieval – that is, incoherent, anti-sexual, self-dramatising and guilt-ridden – religiosity, and follows through this conception of a non-meeting of minds to the unconventional conclusion that Julian’s counsel failed because ‘Margery didn’t really hear what she had to say.’40

However, the most widely circulated scene of Julian as counsellor was published in 1954, when The Book of Margery Kempe was known only to a handful of academic medievalists. In Anya Seton’s still-popular bodice-ripper Katherine, Julian’s advice saves the heroine, Katherine Swynford, from despair. Seton’s Julian represents an interiorized, indeed proto-Protestant, piety. She discourages physical penance and the ‘shining mist’ of her face is contrasted with the ‘bland, wooden, indifferent’ face of the statue of the Virgin at Walsingham, represented in traditional anti-Catholic fashion as an imposition on the credulous.41 The imaginative task Seton sets herself is that of putting Julian in dialogue with a historically attested contemporary whose career and concerns would seem on the face of it quite alien to her. Seton shares the perception of John Swanson that Julian’s thought constitutes an effective pastoral theology.42 Katherine begins the episode sceptical that Julian’s spiritual knowledge has any relevance to her personal troubles, but Seton constructs a dialogue in which passages from A Revelation are adapted as Julian’s response to Katherine’s depression:

‘Lady’, whispered Katherine, ‘it must be these visions were vouchsafed to you because you knew naught of sin – not sins like mine – lady, what would you know of – of adultery – of murder –’

Julian rose quickly and placed her hand on Katherine’s shoulder. At the touch, a soft rose flame enveloped her, and she could not go on.

‘I have known all manner of sin’, said Julian quietly. ‘Sin is the sharpest scourge. … Yet listen to what I was shown … He turned on me His face of lovely pity and he said: it is truth that sin is the cause of all this pain: sin is behovable – none the less all shall be well.’43

Plate 2. ‘Pantheon: Julian of Norwich’, a cartoon by Martin Rowson, Independent on Sunday, 8 March 1998, by kind permission of the artist.

The ensuing conversation, continuing this juxtaposition of romantic narrative with direct quotation, is occasionally awkward, but it is the product of a synthetic historical imagination.

The identification of a recluse as a counsellor helps modern readers to familiarize anchoritism. It counters arguments that the anchoritic life is solipsistic or quietist without either endorsing the very concrete late-medieval attitude to prayer-treasuries or having recourse to functionalist anthropological explanations, such as those which see the recluse as a communal safety-valve, enacting the virtues which a mercantile society cannot afford to practise for itself. Leech imagines Julian counselling John Ball, in order to argue that ‘Her life of solitude was not a selfish, egotistical withdrawal … but a life of love, warmth and care towards her “even-Christians”.’44 The counselling scene also appeals to feminist commentators as an exercise in practical sisterhood, which shows Julian able to bond with a woman of a different style of piety, such as Margery Kempe, or a secular woman, such as Katherine Swynford.

It is presumably this incarnation of Julian as supreme agony aunt which accounts for her presence on the back cover of Donna Freitas’s Becoming a Goddess of Inner Poise: ‘With InStyle magazine on one nightstand, and Julian of Norwich on the other, author Donna Freitas has her finger on the pulse of a new generation of women and understands the spiritual issues that most concern them.’ This is particularly telling because Freitas in fact does not synthesize or adapt Julian’s thought to present-day concerns, but invokes her only to reject her as irredeemably medieval:

How does Chick Lit stand up spiritually to the likes of Showings, by Julian of Norwich – nun-extraordinaire from the fourteenth century (as Julian was not doing a lot of shagging, nor hitting the bottle, except perhaps at church and then in v. limited quantities, I assume). … Can the likes of Bridget Jones’s Diary and Confessions of a Shopaholic prove to be sacred stories?45

Julian is entirely irrelevant to Freitas’s pursuit of the spiritual message of chick-lit, and is invoked only to be superseded. The blurb-writer, however, evidently assumed that it is obligatory to cite Julian in any Christian text directed at women.

Such perfunctory invocations of Julian construct an object ripe for satire. Reductive constructions of Julian as counsellor, nurturer and optimist are ridiculed in Martin Rowson’s ‘Pantheon’ cartoon (Plate 2), in which the anchorhold is modernized into the secular feminine confessional enclosure of the hairdressing salon. Julian, often feminized to ‘Juliana’, or to ‘Dame’, ‘Lady’ or ‘Mother’ Julian, is here an androgynous figure seen dimly through the glass.46 ‘All shall be well’ becomes phatic soothing, emptied of content.

A final example of the modernisation of Julian is the invention of Julian’s cat. This animal originates in Ancrene Wisse’s permission for anchoresses to keep a cat and appears in several images, including the very high-profile window in St Saviour’s chapel, Norwich Cathedral, as a visual signifier of anchoritism.47 This symbolic image is then read as evidence of the historical existence of an actual cat. The cat has made its way from iconography to narrative fiction and has even become the protagonist of a children’s book, Julian’s Cat.48 Pantaleo takes the cat as a given, and weaves it into the plot with the detail that it could sense Julian’s impending visions.49 The cat rounds off the construction of a domesticated persona of Julian as an altogether cosier kind of single woman than the enclosed career-virgin and learned theologian which she was.

The comparison of Julian with her contemporary, Margery Kempe, is irresistible and instructive, for Margery has also been reimagined as our contemporary, but by an entirely different constituency. Margery, though predicted a local cult in her Book, has not acquired a significant devotional following. Julian’s words have been frequently excerpted, with the first and most popular pocket-book of quotations, Enfolded in Love, selling around 100,000 copies.50 I know of only one devotional booklet of quotations from Margery, and even that introduces her with the qualification that she was ‘not a teacher’ but a ‘housewife’.51 The leaflet sold at Margery’s parish church, St Margaret’s, King’s Lynn, describes her as ‘more than just a pilgrim’, but stops well short of endorsing her as saint or mystic.52 Margery’s current constituency is instead dominated by academics, to some of whom she is a figure of more than historical interest. She has recently become one of the key exhibits of the branch of postmodern literary theory which Jeffrey Jerome Cohen calls ‘critical temporal studies’, and which disrupts the concept of time as moving at uniform speed in a single linear direction.53 Carolyn Dinshaw considers Margery as an exemplar of queerness, arguing that her misfit with her contemporaries makes her ‘an anachronism even in her own (temporally heterogeneous) time’ and recommends reading her in a simultaneously historicized and dehistoricized fashion, as a figure who ‘lives in a multitemporal, heterogenous now’ and can be ‘a life possibility for the present’.54 The non-academic public for Julian, however, has for years been operating under the assumption that Julian offers a life possibility for the present, and indeed that she belongs more properly to the present than to the Middle Ages in which she happened to live and write.

* Versions of this material were delivered at the Uses of the Past Conference, Norwich, July 2006, the New Chaucer Society Congress, New York, July 2006 and the Gender and Medieval Studies Group Conference, Norwich, January 2007: thanks to the organisers and to all who attended.

1 Alexandra Barratt, ‘How Many Children Had Julian of Norwich? Editions, Translations and Versions of her Revelations’, in Vox Mystica: Essays on Medieval Mysticism in Honour of Professor Valerie M. Lagorio, ed. Anne Clark Bartlett (Cambridge, 1995), pp. 27–39 (27).

2 The British Library catalogue lists twenty-five versions of Julian’s text, and Amazon.co.uk has twenty-nine.

3 Alan Wilson, Our Faith is a Light: For Soprano Solo, S.A.T.B. Choir and Organ (London, 1985).

4 All references to Julian’s writing will be taken from The Writings of Julian of Norwich: A Vision Showed to a Devout Woman and A Revelation of Love, ed. Nicholas Watson and Jacqueline Jenkins (Turnhout, 2006) and will be cited by section/chapter and line.

5 Sheila Upjohn, Why Julian Now? A Voyage of Discovery (London, 1997), p. 131.

6 Kenneth Leech, ‘Hazelnut Theology: Its Potential and Perils’, in Kenneth Leech and Benedicta Ward, Julian Reconsidered, (Oxford, 1988), pp. 1–9 (5).

7 Ed Block, ‘Interview with Denise Levertov’, Renascence 50, 1–2 (1997), pp. 4–15 (7); Denise Levertov, ‘The Showings: Lady Julian of Norwich, 1342–1416’, in Breathing the Water (New York, 1987), pp. 75–82, section 4.

8 Writings, ed. Watson and Jenkins, p. 20.

9 Hildegard of Bingen, Scivias, trans. Columba Hart and Jane Bishop (New York, 1990), p. 93.

10 Sarah Law, ‘Two Mystical Poems’, in The Lady Chapel (Exeter, 2003), pp. 40–1.

11 Iris Murdoch, Nuns and Soldiers (London, 1980), p. 62.

12 Ibid., p. 292.

13 Anchoress, dir. Chris Newby (1993). Thanks to Jacqueline Jenkins whose paper, ‘Styling History: Aesthetics and Authority in The Anchoress and The Navigator’, at The Middle Ages on Film conference, St Andrews, July 2005, alerted me to this connection and to Liz Herbert McAvoy for the gift of a copy of the film.

14 Copies and translations of the documents of her enclosure and re-enclosure are displayed in St James’s Church, Shere, Surrey, for an analysis of which see Liz Herbert McAvoy, ‘Gender, Rhetoric and Space in the Speculum Inclusorum, Letter to a Bury Recluse and the Strange Case of Christina Carpenter’, in Rhetoric of the Anchorhold: Place, Space and Body in the Discourses of Enclosure, ed. Liz Herbert McAvoy (Cardiff, 2008 forthcoming), pp. 111–26. See also Miri Rubin, ‘An English Anchoress: The Making, Unmaking and Remaking of Christine Carpenter’, in Pragmatic Utopias: Ideals and Communities 1200–1630, ed. Rosemary Horrox and Sarah Rees Jones (Cambridge, 2001), pp. 204–17 for further detail on the historical record and the film.

15 Frodo Okulam, The Julian Mystique: Her Life and Teachings (Ottawa, 1998), p. 1.

16 Jack Pantaleo, Mother Julian and the Gentle Vampire (Roseville, 1999), p. 4. Thanks to Sarah Law for telling me about this book.

17 Karen Armstrong, The End of Silence: Women and the Priesthood (London, 1993), p. 139.

18 http://www.ecusa.anglican.org/75383_76300_ENG_HTM.htm.

19 Sheila Upjohn, In Search of Julian of Norwich (London, 1989), pp. 53, 51.

20 T. S. Eliot, Collected Poems 1909–1962 (London, 1974), p. 223.

21 C. S. Lewis, Collected Letters vol. II: Books, Broadcasts and War 1931–1949, ed. Walter Hooper (London, 2004), p. 369.

22 Leech, ‘Hazelnut Theology’, p. 7.

23 Iris Murdoch, The Black Prince (London, 1999), p. 221. The butt of a baroque Murdochian plot, he dies while wrongfully imprisoned for the murder of a rival writer, having been framed by the victim’s vengeful wife, jealous of his love for her daughter, Julian.

24 Michael McLean, ‘Introduction’, in Julian: Woman of our Day, ed. Robert Llewelyn (London, 1985), pp. 1–10 (2).

25 Benedicta Ward, ‘Julian the Solitary’, in Leech and Ward, Julian Reconsidered, pp. 11–35 (23). The argument had been made previously, but Ward’s version has circulated most widely.

26 Upjohn, Why Julian Now? p. 118.

27 Dana Bagshaw, Cell Talk, performed by Cameo Theatre Company, St Julian’s, Norwich, 11 September 2005; Anya Seton, Katherine (London, 1954), p. 514.

28 Ralph Milton, Julian’s Cell: An Earthly Story of Julian of Norwich (Kelowna, 2002). I am grateful to Daniel Pinti for letting me know of this text.

29 Milton, Julian’s Cell, pp. 27, 30, 199.

30 Milton, Julian’s Cell, p. 34.

31 Sheila Upjohn, Mind out of Time (Norwich, 1979), p. 15.

32 Upjohn, Why Julian Now? p. 86.

33 Pantaleo, Mother Julian, p. 88.

34 Ancrene Wisse, trans. Hugh White (Harmondsworth, 1993), p. 35.

35 The Book of Margery Kempe, ed. Sanford Brown Meech and Hope Emily Allen, EETS o.s. 212 (London, 1940), p. 42; see Nancy Caciola, Discerning Spirits: Divine and Demonic Possession in the Middle Ages (Ithaca, NY, 2003) for the intense anxiety raised by this problem and Naöe Kukita Yoshikawa, Margery Kempe’s Meditations: The Context of Medieval Devotional Literature, Liturgy and Iconography (Cardiff, 2007), pp. 62–7 for a discussion of the issue in the Book. I am grateful to Naöe for prepublication access to her work.

36 Robert Llewelyn, With Pity not Blame: The Spirituality of Julian of Norwich and The Cloud of Unknowing (London, 1982), p. 6.

37 Brian Thorne, Mother Julian, Radical Psychotherapist, Annual Julian Lecture 1993 (Norwich, undated), p. 7.

38 Brian Thorne, Julian of Norwich: Counsellor for our Age (London, 1999), p. 17.

39 Law, Lady Chapel, pp. 37–9.

40 Milton, Julian’s Cell, p. 200.

41 Seton, Katherine, p. 511, p. 502.

42 John Swanson, ‘Guide for the Inexpert Mystic’, in Julian: Woman of our Day, ed. Llewelyn (London, 1985), pp. 75–88 (87).

43 Seton, Katherine, p. 511

44 Kenneth Leech, ‘Contemplative and Radical: Julian meets John Ball’, in Julian: Woman of our Day, ed. Llewelyn (London, 1985), pp. 89–101 (90).

45 Donna Freitas, Becoming a Goddess of Inner Poise: Spirituality for the Bridget Jones in All of Us (San Francisco, 2005), p. 9. Thanks to Anke Bernau for telling me of this book.

46 ‘Dame Ielyan’, is used in The Book of Margery Kempe, but there is no contemporary attestation for the other titles; Book of Margery Kempe, p. 42.

47 Ancrene Wisse, p. 192.

48 Mary E. Little, Julian’s Cat: The Imaginary History of a Cat of Destiny (Wilton, 1989).

49 Pantaleo, Mother Julian, p. 262.

50 Enfolded in Love: Daily Readings with Julian of Norwich, ed. Robert Llewelyn (London, 1980); Robert Llewelyn, Memories and Reflections (London, 1998), p. 183.

51 The Mirror of Love: Daily Readings with Margery Kempe, ed. Gillian Hawker (London, 1988), p. vii.

52 Elizabeth James, The St Margaret’s of Margery Kempe, pamphlet.

53 Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Medieval Identity Machines (Minneapolis, 2003), p. 9.

54 Carolyn Dinshaw, ‘Margery Kempe’, in The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Women’s Writing, ed. Caroline Dinshaw and David Wallace (Cambridge, 2003), pp. 222–39 (236, 237).