Jīng Wu student: “Look here! Now, just what is the point of this?”

Translator: “Just that the Chinese are a race of weaklings, no comparison to us Japanese.”

– Fist of Fury, dubbed version

Jīng Wu student: “One question, are you Chinese?”

Translator: “Yes, but even though we are of the same kind, our paths in life are vastly different”

– Fist of Fury, subtitled version1

DIFFERENT LEE

Bruce Lee has always been construed as a figure who existed at various crossroads – a kind of chiasmatic figure, into which much was condensed, and displaced. His films, even though in a sense being relatively juvenile action flicks, have also been regarded as spanning the borders and bridging the gaps between ‘trivial’ popular culture and ‘politicised’ cultural movements (see Brown 1997; Morris 2001; Prashad 2001; Kato 2007). That is, although on the one hand, they are all little more than fantastic choreographies of aestheticised masculinist violence, on the other, they worked to produce politicised identifications and modes of subjectivisation that supplemented many popular-cultural-political movements: his striking(ly) nonwhite face and unquestionable physical supremacy in the face of often white, always colonialist and imperialist bad-guys became a symbol of and for multiple ethnic, diasporic, civil rights, anti-racist and postcolonial cultural movements across the globe (see Prashad 2001; Kato 2007). Both within and ‘around’ his films – that is, both in terms of their internal textual features and in terms of the ‘effects’ of his texts on certain viewing constituencies – it is possible to trace a movement from ethnonationalism to a postnational, decolonising, multicultural imaginary (see Hunt 2003). This is why his films have been considered in terms of the interfaces and interplays of popular culture, postcolonial, postmodern and multiculturalist issues that they have been deemed to ‘reflect’, engage, dramatise, explore or develop (see Abbas 1997; Hunt 2003; Teo 2008). Lee has been credited with transforming intra- and inter-ethnic identification, cultural capital and cultural fantasies in global popular culture, and in particular as having been central to revising the discursive constitutions and hierarchies of Eastern and Western models of masculinity (see Thomas 1994; Chan 2000; Miller 2000; Hunt 2003; Preston 2007).

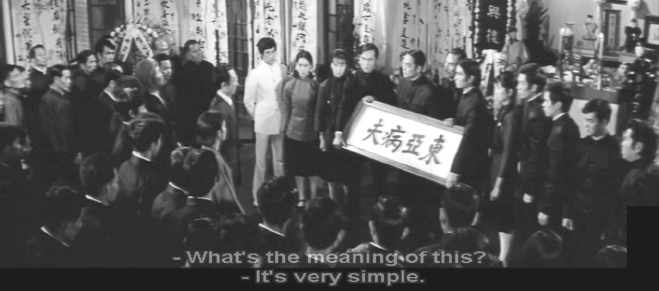

Figure 10: Fist of Fury

In the wake of such well-known and well-worn approaches to Bruce Lee, I would prefer at this point to take these types of arguments as read, and propose from here on to approach Lee somewhat differently – maybe peculiarly, perhaps even queerly. Specifically, I would like to propose that his celluloid cinematic interventions – no matter how fantastic and fabulous – ought to be approached as texts and contexts of cultural translation. However, to say this, a rather twisted or indeed ‘queer’ notion of translation needs to be established. To speak of cultural translation is not to simply refer to translation in a linguistic or hermeneutic sense. It is rather to be understood as something less ‘literal’ (or logocentric); as what Rey Chow calls ‘an activity, a transportation between two “media”, two kinds of already-mediated data’ (1995: 193). Furthermore, cultural translation would also be understood as a range of processes which mean that, for academics, ‘the “translation” is often what we must work with because, for one reason or another, the “original” as such is unavailable – lost, cryptic, already heavily mediated, already heavily translated’ (ibid.).

This is not a particularly unusual situation, of course. It is, rather, everyday. Such translated, mediated, commodified, technologised exchanges between cultures happen every day. This is also the situation we are in when encountering film, especially films that are dubbed or subtitled, of course, as in the case of Bruce Lee’s Hong Kong-produced films. Such films are translated, dubbed and subtitled. But this is not the start or end of translation. For the notion of cultural translation demands that we extend our attention beyond the scripts and into the matter of the very medium of film itself, the relations between films, between film and other media, and so on. This is important to emphasise because, despite its everydayness, despite its reality, and despite the arguable primacy of the situation of cultural translation between ‘translations’ with no (access to any) original, this situation of cultural translation is not often accorded the status it could be said to deserve. It is rather more likely to be disparaged by scholars, insofar as it occurs predominantly in the so-called ‘realms’ of popular culture and does not conform to a model of translation organised by the binary of ‘primary/original’ and ‘derived/copy’ (Chow 1995: 182). As Chow asks:

how is it that colleagues in the discipline of comparative literature tend to love the idea of translation – which, as a topic, is perhaps one of the most heavily theorized in the field – but at the same time seem to scorn the use of translated works for research and pedagogical purposes as improper, inauthentic, low-rent, etc., even in a comparative context? (2010: 456)

In awareness of this, Chow proposes that ‘the problems of cross-cultural exchange – especially in regard to the commodified, technologized image – in the postcolonial, postmodern age’ (1995: 182) demand an approach that moves beyond many traditional approaches. For instance, she points out, as well as the ‘literal’ matters of translation that arise within film, ‘there are at least two [other] types of translation at work in cinema’ (ibid.). The first involves translation understood ‘as inscription’: any film is a kind of writing into existence of something which was not there as such or in anything like that way before its constitution in film. The second type of translation associated with film, proposes Chow, involves understanding translation ‘as transformation of tradition and change between media’; in this second sense, film is translation insofar as a putative entity (she suggests, ‘a generation, a nation, [or] a culture’) are ‘translated or permuted into the medium of film’ (ibid.). So, film as such can be regarded as a kind of epochal translation, in the sense that cultures ‘oriented around the written text’ were and continue to be ‘in the process of transition and of being translated into one dominated by the image’ (ibid.). As such,

the translation between cultures is never West translating East or East translating West in terms of verbal languages alone but rather a process that encompasses an entire range of activities, including the change from tradition to modernity, from literature to visuality, from elite scholastic culture to mass culture, from the native to the foreign and back, and so forth. (1995: 192)

It is here that Bruce Lee should be placed. However, given the complexity of this ‘place’ – this relation or these relations – it seems likely that any translation or indeed any knowledge we hope might be attained cannot henceforth be understood as simple unity-to-unity transport. This is not least because the relations and connections between Bruce Lee and … well, anything else, will now come to seem always shifting, immanent, virtual, open-ended, ongoing and uncertain. This is so much so that the very notions of completeness, totality or completion are what become unclear or incomplete in the wake of ‘cultural translation’. In other words, this realisation of the complexity of cultural relations, articulations and encounters jeopardises traditional, established notions of translation and knowledge-establishment. Yet it does not ‘reject’ them or ‘retreat’ from them. Rather, it transforms them.2

To elucidate this transformation, Chow retraces Foucault’s analyses and argument in The Order of Things (1970) in order to argue that both translation and knowledge per se must henceforth be understood as ‘a matter of tracking the broken lines, shapes, and patterns that may have become occluded, gone underground, or taken flight’ (2006: 81).3 Referring to Foucault’s genealogical work on the history of knowledge epistemes in The Order of Things, Chow notes his contention that ‘the premodern ways of knowledge production, with their key mechanism of cumulative (and inexhaustible) inclusion, came to an end in modern times’; the consequence of this has been that ‘the spatial logic of the grid’ has given way ‘to an archaeological network wherein the once assumed clear continuities (and unities) among differentiated knowledge items are displaced onto fissures, mutations, and subterranean genealogies, the totality of which can never again be mapped out in taxonomic certitude and coherence’ (ibid.). As such, any ‘comparison’ must henceforth become ‘an act that, because it is inseparable from history, would have to remain speculative rather than conclusive, and ready to subject itself periodically to revamped semiotic relations’; this is so because ‘the violent yoking together of disparate things has become inevitable in modern and postmodern times’ (ibid.). As such, even an act of ‘comparison would also be an unfinalizable event because its meanings have to be repeatedly negotiated’; this situation arises ‘not merely on the basis of the constantly increasing quantity of materials involved but more importantly on the basis of the partialities, anachronisms, and disappearances that have been inscribed over time on such materials’ seemingly positivistic existences’ (ibid.).

To call this ‘queer’ may seem to be stretching – or twisting, contorting – things a bit. Clearly, such a notion of translation can only be said to be queer when ‘queer’ is understood in an etymological or associative sense, rather than a sexual one. Nevertheless, it strikes me that the most important impulse of queer studies was its initial and initialising ethico-political investment in stretching, twisting and contorting – with the aim of transforming – contingent, biased and partial societal and cultural norms.4 This is an element of queering that deserves to be reiterated, perhaps over and above queer studies’ always-possibly socially ‘conservative’ investment in sexuality as such (see Chambers and O’Rourke 2009). This is so if queering has an interest in transforming a terrain or a context rather than just establishing a local, individual enclave for new norms to be laid down. I believe that it does, which is one of the reasons that it seems worthwhile to draw a relation between cultural translation and queering, given their shared investments in ‘crossing over’, change, twisting, turning and warping. Given the undisputed and ongoing importance of Bruce Lee within or across the circuits of global popular culture, crossing from East to West and back again, as well as from film to fantasy to physicality, and other such shifting circuits, it seems worthwhile to consider the status of ‘crossing over’ in (and around) Bruce Lee films.

EXCESSIVE LEE

To bring such a complicated theoretical apparatus to bear on Bruce Lee films may seem excessive. This will be especially so because, as Kwai-Cheung Lo argues, most dubbed and subtitled martial arts films from Hong Kong, China or Japan have traditionally been approached not with cultural theories to hand but rather with buckets of popcorn and crates of beer, as they have overwhelmingly been treated as a source of cheap laughs for Westerners (2005: 48–54). Indeed, as Leon Hunt has noted, what is ‘loved’ in the ‘Asiaphilia’ of kung fu film fans is mainly ‘mindlessness’ – the mindless violence of martial arts. Like Lo, Hunt suggests that therefore even the Asiaphilia of Westerners interested in Eastern martial arts ‘subtly’ amounts to yet another kind of Orientalist ‘encounter marked by conquest and appropriation’ (2003: 12).

Lo’s argument has an extra dimension, however, in that as well as focusing on the reception of these filmic texts in different linguistic and cultural contexts, he also draws attention to the realm of production. Yet even this, in Lo’s terms, is far from theoretically complex: in Hong Kong film, he writes, ‘the process of subtitling often draws attention to itself, if only because of its tendency toward incompetence’ (2005: 48). Nevertheless, he suggests, ‘as a specific form of making sense of things in cross-cultural and cross-linguistic encounters, subtitling reveals realities of cultural domination and subordination and serves as a site of ideological dissemination and its subversion’ (2005: 46).5 For Lo, then, despite a base level of material ‘simplicity’ here, complex issues of translation do arise, and not simply with the Western reception of Eastern texts, but actually at the site of production itself, no matter how slapdash. As he sees it,

Unlike film industries that put a great deal of care into subtitles, Hong Kong cinema is famous for its slipshod English subtitling. The subtitlers of Hong Kong films, who are typically not well educated, are paid poorly and must translate an entire film in two or three days. (2005: 53)

At the point of reception or consumption, Lo claims, the ‘English subtitles in Hong Kong film often appear excessive and intrusive to the Western viewer’. Drawing on a broad range of Žižeko-Lacanian cultural theory, Lo suggests that the subtitles are ‘stains’ and that ‘just as stains on the screen affect the visual experience, subtitles undermine the primacy and immediacy of the voice and alienate the aural from the visual’ (2005: 49). In this way, by using one of Žižek’s favourite double-entendres – the crypto-smutty, connotatively ‘dirty’ word ‘stain’ (a word which, for Žižek, often signals the presence or workings of ‘the real’ itself) – and by combining it with a broadly Derridean observation about the interruption of the self-presence of auto-affection in the frustration of cinematic identification caused by non-synchronised image-and-voice and image-and-written-word, Lo crafts an argument that is all about excess.

The subtitles are excess. Their meaning is excess: an excess of sameness for bilingual viewers, and an excess of alterity for monolingual viewers. For the bilingual, who both hear and read the words, they produce both excessive emphases and certain discordances of meaning, because of their spatial and temporal discordances and syncopations with the soundtrack. But, Lo claims, ‘to a presumptuous Western audience, the poor English subtitles make Hong Kong films more “Chinese” by underscoring the linguistic difference’ (2005: 51). Thus, for bilingual viewerships (such as many Hong Kong Chinese, who have historically been able to speak both English and Cantonese), the subtitles introduce an excess that simultaneously introduces alterity through their fracturing and alienating effects. For monolingual ‘foreign’ viewerships, Lo argues, the subtitles also produce an ‘extra’ dimension: a very particular, form of pleasure and enjoyment. This extra is not extra to a primary or proper. It is rather an excess generated from a lack. It is an excess – pleasure, amusement, finding the subtitles ‘funny’. And Lo’s primary contention is that, in this sense, the subtitles actually preclude the possibility of a proper ‘weight’ or ‘gravity’ for the films; that they are a supplement that precludes the establishment of a proper status, a proper meaning, a properly ‘non-excessive’ non-‘lite’/trite status.

Thus, the subtitles are a visual excess, Lo contends.6 For monolingual or euro-lingual viewers, the visual excess is the mark (or stain) which signifies a semantic lack. This might be a mark of viewers’ own inability and lack of linguistic and cultural knowledge rather than any necessary semantic deficiency in the text itself; but the point is, argues Lo, ‘the words onscreen always consciously remind viewers of the other’s existence’ (2005: 48). In either case, this very lack generates an excess. As Lo puts it, ‘the fractured subtitles may puzzle the viewers who need them, and yet they also give rise to a peculiar kind of pleasure’; that is, ‘the articulation of the loss of proper meaning offers a pleasure of its own to those who treasure alternative aesthetics and practice a radical connoisseurship that views mass culture’s vulgarity as the equal of avant-garde high art’ (2005: 54). Lo calls this the pleasure of ‘being adrift’: ‘Drifting pleasure occurs when definite meaning can no longer be grasped. Bad English subtitles may kindle a kind of pleasure that was never meant to be there’ (ibid.), he proposes; going on to insist that

A subtitled Hong Kong film received in the West produces a residual irrationality that fascinates its hardcore fans. Apparently, a dubbed Hong Kong film would not offer the same sort of additional fun. The distorted meaning of the English subtitles is not to be overlooked. On the contrary, the distortion is written into the very essence of Hong Kong films and is one of the major appeals for Western fans. It is an unexpected boon that increases the viewer’s already considerable enjoyment. (2005: 56)

Thus, he argues against the suggestions of commentators like Antje Ascheid who have proposed that subtitled film fundamentally ‘contains a number of reflexive elements which hold a much larger potential to break cinematic identification, the suspension of disbelief and a continuous experience of unruptured pleasure’ (quoted in ibid.). Ascheid argues that subtitled films construct a ruptured space ‘for intellectual evaluation and analysis’ insofar as this confluence of features ‘destroys the usual unity between the spectator and the cinematic world he or she experiences [and] results in the perception of “difference” rather than the confirmation of “sameness” and identity’, which ‘potentially leads to a considerable loss of pleasure during the experience’ (quoted in ibid.). Against such arguments, Lo proposes that ‘In the case of subtitled Hong Kong films, these arguments are no longer valid’; this is because, with these martial arts films, the ‘disruption of cinematic identification and the perception of difference might generate extra enjoyment but never a loss of pleasure’ – in martial arts films, suggests Lo, ‘rupture does not necessarily give rise to “intellectual evaluation and analysis”; rather, it lends to a film’s fetishistic appeal’ (ibid.).

STUPID LEE

So, the subtitles are constructed with ‘incompetence’ by the undereducated and underpaid subtitlers. They are destined to be an unnecessary supplement for Chinese speakers and an excessive supplement for those who can also read Chinese. For Westerners, these supplements are destined to work to turn the movies into a joke. Indeed, apart from the thrills to be gained from watching the physical action of the martial choreography, the subtitles are destined to become the fetish defining the nature of Western viewers’ interest in Hong Kong films.

It has been well-documented in Western film guides and critical studies of Hong Kong films that the English subtitles are not viewed simply as troublesome but also as great fun for Western viewers. In the West, Hong Kong cinema enjoys great popularity among nonconformist subcultures – festival circuits, college film clubs, Internet fanzines, and fan groups – in which cult followers and lovers of camp celebrate the exploitation and peculiarities on display […]; its wild and weird subtitles further elevate the cinema’s fetishistic status and exotic flavor. The tainted object that obscures part of the screen and confuses the signification has been sublimated into a cult element by hardcore fans who look for off-center culture and down-market amusements. (Lo 2005: 54)

Fun, off-centre, camp, incompetent, uneducated, excessive, physical, intrusive: the way Lo constructs and represents Hong Kong cinema ‘in general’ is not particularly far removed from the way that the Hollywood camera constructs the bumbling, bothersome Mr Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (see Morris 2001). Of course, Lo is putatively dealing with the ‘reception’ and ‘interpretation’ of Hong Kong films by Western viewers. Thus, according to him, it is the Western viewers, in (and through) their ignorance, who construct the dubbed Hong Kong films as low-brow, ‘down-market amusements’. But the likelihood or generality of such a reception is overdetermined by the conspiring factors of undereducated subtitlers who are, moreover, overworked and underpaid by an industry in a hurry to shift its product. Thus, even if the Hong Kong films are sophisticated, complex texts, this dimension is going to be forever foreclosed to the monolingual or euro-lingual Western viewer. What is lost in the double translation from living speech to incompetent writing is logos. What remains is the nonsense of the body and some gibberish, unintelligible baby-talk. As such, the only people could possibly be interested in such a spectacle, are, of course, stupid people.

Lo does not say this explicitly, but everything in his argument suggests the operation of a very familiar logic: the denigration of popular culture; the conviction that it is stupid. In his own words, the badly subtitled film entails ‘the loss of proper meaning [which] offers a pleasure of its own to those who treasure alternative aesthetics and practice a radical connoisseurship that views mass culture’s vulgarity as the equal of avant-garde high art’ (2005: 54). Thus, to Lo, ‘mass culture’ is characterised by ‘vulgarity’ and is not the equal of ‘avant-garde high art’. Popular culture is stupid.

Lo’s attendant argument, that the clunky subtitles are not really an ‘obstacle’ to the smooth global circulation of commodities, but rather the condition of possibility for the success of the martial arts films, is similar. As he claims: ‘globalization is facilitated by the “hindrance” or the “symbolic resistance” inherent in the clumsy English subtitles – which represent a certain cultural specificity or designate certain ethnic characteristics of the port city’ (ibid.). Thus, Lo imagines the appeal of such films to be entirely fetishistic and ultimately racist. For, in his conceptualization, what Western audiences want is a foreignness to laugh at. As such, it is the films’ very palpable foreignness which helps them to succeed. Indeed, he concludes, ‘the subtitles as good and pleasing otherness are actually founded on the exclusion of the political dimension usually immanent in the encounter of the cultural other’ (2005: 58). This is a core dimension of Lo’s argument: ‘Hong Kong cinema is basically perceived as a “good other” to the American viewer insofar as it is analogous to the old Hollywood’ (2005: 57). Thus, for Lo, the matter of subtitles in Hong Kong film ultimately amounts to a process of depoliticisation. Yet is this in fact the case?

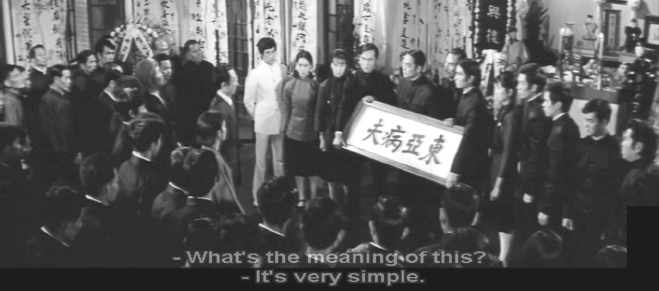

Figure 11: Questioning the Translator

ORIGINAL LEE

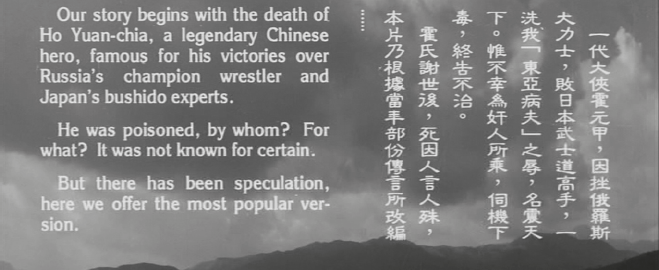

The 1972 international blockbuster Fist of Fury (also known as Jīng Wu Mén in Chinese and The Chinese Connection in America) begins with a burial. The founder of the Jīng Wu martial arts school in the Shanghai International Settlement (1854–1943) – the much mythologised historical figure, Huo Yuanjia – has died (1910). Before the very first scene, a narrator tells us that the events surrounding Master Huo’s death have always been shrouded in mystery, and that the film we are about to watch offers ‘one possible version’ (‘the most popular version’) of what may have happened. What happens – or what could have happened, according to this fable – is that Huo’s favourite pupil, Chen Zhen, played by Bruce Lee, returns to the Jīng Wu School and refuses to accept that his master died of natural causes.

At the official funeral the next day, an entourage from a Japanese Bushido School arrive, late. They bear a gift, as was traditional. But the gift turns out to be an insult and a provocation: a framed inscription of the words ‘Sick Man of Asia’ (dōng yà bìng fū). Upon delivering this, the Japanese throw down a challenge, via their intermediary, the creepy, effeminate and decidedly queer translator called Wu (or, sometimes, Hu): if any Chinese martial artist can beat them, the Japanese martial artists will ‘eat these words’.

So begins what has become regarded as a martial arts classic. The film is organised by Bruce Lee’s Chen Zhen’s ultimately suicidal quest for revenge against what turns out to have been not merely a Japanese martial arts challenge (Lee of course picks up the gauntlet thrown down by the Japanese – besting the entire Japanese school single-handedly the next day, in a fight scene that made martial arts choreographic history and is still clearly referenced in myriad fight scenes of all action genres to this day) but also a murderous piece of treachery: Lee subsequently discovers that his master was poisoned by two imposters who had been posing as Chinese cooks, but who were really Japanese spies. Again, their intermediary, their contact, the communicator of the orders, was the translator, Mr Wu. Thus, what begins with a crass and irreverent ethnonationalist slur at a Chinese master’s funeral turns out to be part of a concerted plot to destroy the entire Chinese institution. As Fist of Fury makes clear, the assassination and the plot to destroy Jīng Wu arose precisely because the Japanese were deeply concerned that the Chinese were far from being ‘sick men’, were actually too healthy, and could become too strong and pose too much of a potential challenge to Japanese power, if left to their own devices. However, as the film also makes clear, in this colonial situation, the odds have been stacked against the Chinese from the outset – no matter what they decide to do, they will not be left alone or allowed to prosper.

Figure 12: The opening frames of Fist of Fury

The translator is the first point of contact between the two cultures. The first face-to-face conscious contact follows the earlier behind-the-back, underhand and unequal contact of spying and assassination. To the Chinese, Wu is consistently belligerent, disrespectful and abusive. To the Japanese he is an obsequious crawler. On first face-to-face contact, at the funeral, Wu taunts the mourners, telling them that they are weak, pathetic and no better than cowardly dogs – simply because they are Chinese. A senior Chinese student (played by James Tien Chun) is evidently confused: he approaches Wu and demands an answer to one question. In the dubbed English version the question is: ‘Look here! Now, just what is the point of this?’ And the answer is given: ‘Just that the Chinese are a race of weaklings, no comparison to us Japanese.’ So, here, Wu is Japanese. However, in the English subtitled version, the question and answer are somewhat different. Here, the Chinese student says: ‘One question, are you Chinese?’ To this, the answer is: ‘Yes, but even though we are of the same kind, our paths in life are vastly different.’ So here, Wu is Chinese.

This disjunction between the subtitled version and the dubbed version may seem only to raise some fairly mundane questions of translation: namely, which version is correct, which version is faithful to the original? If by original we mean the Cantonese audio track, then, in this instance at least, it is the subtitles which follow it most closely.7 But, as my act of distinguishing the audio tracks from the visual material implies, it seems valid to suggest, precisely because it is possible to separate out these various elements, that it is the very notion of the original here that should be engaged. For, the film was ‘shot post-synch’, with the soundtrack added to the film only after the entire film was shot (see Lo 2005: 50). As such, the visual and the aural are already technically divergent, distinct textual combinations, even in the putative ‘original’. So, if we wish to refer to it, the question must be: which original?

It is of more than anecdotal interest to note at this point that the actor who plays the translator here – Paul Wei Ping-Ao – provided the voice over not only for the Cantonese audio but also for the English audio. This means that the actor who plays the translator is also actually an active part of the translation of the text. It also means that the translated version of this film is also another/different ‘original’ version; a secondary, supplementary original, playing the part of a translation. It equally means that, given the overlapping production and translation processes involved in the technical construction of not ‘this film’ but rather ‘these films’, the quest to establish and separate the original from the copy or the original from the translation becomes vertiginous.

Certain binaries are blurred because of this fractured bilinguality. These are the very binaries which fundamentally structure and hierarchise many approaches to translation: fidelity/infidelity, primary/secondary, original/copy, authentic/construction and so on. In fact, these several senses of translation, treachery and tradition all coalesce in the early scene in Fist of Fury. As we have seen, this scene – which initiates and initialises the action of the film – is dominated by an accusation: the Japanese declare that an unnamed addressee is the ‘Sick Man of Asia’. This is a brilliantly efficient insult, as it operates on all salient levels at once: This is the funeral of a Chinese martial arts master who apparently died of a sickness, so he was the sick man; but it is also directed at all Chinese, and equally to the nation of China, whose independence and powers had been drastically compromised by a wide range of foreign onslaughts. Reciprocally, of course, as Jachinson W. Chan (2000) emphasises, this is all organised through the other element of this copula: masculinity. Thus, the vocalisation of the accusation of sickness on all levels comes at a moment of profound cultural crisis. China is in a weakened state – hence the presence of such powerful Japanese in Shanghai. The funeral is that of the traditional Chinese master. Moreover, the deceased master was also the actual founder.

Here, the fractured bilinguality is itself symptomatic of what we might call (following Benjamin) a Chinese ‘intention’ in a text produced in British Hong Kong about Japanese coloniality. This is a multiple-colonised text about a colonial situation produced in a different colonial context. In it, the supposedly stable binaries of text and translation are substantially unsettled. Indeed, this is so much so, I think, that what we are able to see here is what Rey Chow calls a ‘materialist though elusive fact about translation’; namely, to use Walter Benjamin’s proposition, that ‘translation is primarily a process of putting together’ – as Chow explains, for Benjamin, translation is a process which ‘demonstrates that the “original”, too, is something that has been put together’ – and she, following this, adds: ‘in its violence’ (1995: 185). What part does ‘violence’ play, here?

VIOLENT LEE

There are several obvious forms of violence in the putting together of both the English and the Cantonese versions. Obviously there is the well-worn theme of the ethnonationalist violence of the film’s primary drama: Bruce Lee’s fantastic, phantasmatic, suicidal, symbolic victory (even in death) over the Japanese oppressors. But there is also the more subtle ‘violence’ or ‘forcing’ involved in constraining the English dubbing to synching with the lip movements of a different-language dialogue. This is ‘violent’ in its semiotic consequences. For instance, as we have already seen, it violently simplifies the complexity of the translator, Mr Wu. In the dubbed version, he becomes simply Japanese and therefore simply other. And this signals or exemplifies a further dimension. The dubbed version seems consistently to drastically simplify the situation of the film. That is, it dislodges the visibility of the themes of the politics of coloniality that are central to the subtitled (and presumably also to the Cantonese) versions, and empties out the socio-political complexity of the film, transforming it into a rather childish tale of bullies and bullying: in the dubbed version, the Japanese simply bully the innocent and consistently confused Chinese, simply because they are bullies. More complex issues are often elided. This is nowhere more clear than in the difference between the question ‘ni shì Zhōng guó rén ma?’ (‘are you Chinese?’) and the alternative question, ‘just what is the point of this?’

Figure 13: A very symbolic slap in the face; Fist of Fury

However, although ‘are you Chinese?’ is literally faithful to the Cantonese, and although ‘what is the point of this?’ is not, and is more simplistic, I do not want to discount, discard or disparage this literally inadequate translation. This is not least because the question ‘just what is the point of this?’ is surely one of the most challenging and important questions to which academics really ought to respond. It is also because the unfaithful translation is the one which perhaps most enables the film to be transmissible – that is, to make sense elsewhere, in the non-Chinese contexts of the film’s own transnational diasporic dissemination. It has an element of universality. This is to recall Benjamin’s proposal that a work’s ‘transmissibility’ actually arises ‘in opposition to its “truth”’ (Chow 1995: 199). This contention arises in Benjamin’s discussion of Kafka, in which he asserts that: ‘Kafka’s work presents a sickness of tradition’ in which the ‘consistency of truth … has been lost’; thus, suggests Benjamin, Kafka ‘sacrificed truth for the sake of clinging to its transmissibility’ (quoted in ibid.). Picking up on this, Chow adds Vattimo’s Nietzschean proposal that this ‘sickness’ is constitutive of transmissibility and is what enables and drives the ‘turning and twisting of tradition away from its metaphysical foundations, a movement that makes way for the hybrid cultures of contemporary society’ (ibid.).

The primary field of such twisting, turning, concatenation and warping is, of course, that supposed ‘realm’ (which could perhaps be rather better understood as the condition) called mass or popular culture. Thus, argues Chow:

There are multiple reasons why a consideration of mass culture is crucial to cultural translation, but the predominant one, for me, is precisely that asymmetry of power relations between the ‘first’ and the ‘third’ worlds. […] Critiquing the great disparity between Europe and the rest of the world means not simply a deconstruction of Europe as origin or simply a restitution of the origin that is Europe’s others but a thorough dismantling of both the notion of origin and the notion of alterity as we know them today. (1995: 193–4)

JUST WHAT IS THE POINT OF THIS?

The issue of transmissibility might be taken to suggest one of two things: either, ‘just what is the point of this?’ is the more primary or more ‘universal’ question, because it is more transmissible; or this translation/transformation loses the essential stakes of the local specificity of the ethnonationalist question ‘Are you Chinese?’

Rather than adjudicating on the question of transmissibility and (or versus) truth in ‘direct’ terms, it strikes me as more responsible to expose each of these questions to each other. Thus, in the face of the question ‘Are you Chinese?’ we might ask: ‘Just what is the point of this?’ and vice versa. In doing so, we ought to be able to perceive a certain ethnonationalist ‘violence’ lurking in the construction of the former question. For instance, ‘Are you Chinese?’ is regularly levelled – accusingly – at translated or globally successful ‘Chinese’ films. It is often asked aggressively, pejoratively, dismissively – as if simultaneously demanding fidelity and essence, at and the same time suggesting treachery.

The accusative question levelled at Hu the translator strongly implies that if Hu is Chinese, then he, in being a translator, is a traitor. But in Fist of Fury there is more. The translator is a pervertor: a pervertor of tradition, first of all. And also: a very queer character. The film draws a relation between the translator and queerness. It makes the translator queer. Because he crosses over.

According to the Italian expression ‘traduttore, traditore’, a translator is a traitor. Chow starts from this expression and the etymological intertwining of translation, tradition and treachery to consider the always-uneasy cultural place or plight of translation, translating and translators, and the overwhelming tendency for thinking about translation to be ineluctably involved in a fraught negotiation of the ‘ideology of fidelity’ (1995: 183). For the translator and the translation must be ‘faithful’, in some sense. But what is being asked of any act of translation would seem to be an act of infidelity, of moving over into alterity. Furthermore, Chow’s work implies, the problematic of fidelity and infidelity here has at least two kinds of connotation. The first is related to depth versus superficiality. The second is related to transmission, transgression and tradition. An incompetent translation is easily thought of as one which is unable to ‘plumb the depths’ and transfer them with fidelity; it is regarded as merely ‘surface’ or ‘superficial’ in some way. In other words, unless the translated work can somehow prove itself to have carried over the ‘depth’ of the original, it is merely shallow, superficial and unfaithful to the tradition of the original. In a discussion of the discourse of translation as it relates to ‘China’ in ‘Chinese’ film (and films about China produced for or consumed by non-Chinese viewerships), Chow puts the case rhetorically: ‘is not the distrust of “surfaces” … a way of saying that surfaces are “traitors” to the historical depth that is “traditional China”?’ (1995: 183). ‘And yet’, she immediately continues, ‘the word tradition itself, linked in its roots to translation and betrayal, has to do with handing over. Tradition itself is nothing if it is not a transmission. How is tradition to be transmitted, to be passed on, if not through translation? (ibid.).

Given Chow’s rhetorical formulation, she goes on, as one might hope and expect, to zone in on and problematise the terms she has identified as structuring so many approaches to questions of cultural translation: surface/depth, fidelity/ infidelity, original/translation, culture/tradition/transmission/translation and so on. We will explore aspects of Chow’s discussion of the possibilities of ‘cultural translation’ in our discussion of dubbing, subtitling and translation in relation to Fist of Fury. For, these several senses of translation, treachery and tradition all coalesce in the early scene in Fist of Fury.

TRANSMISSION, TRANSGRESSION

The translator and two Japanese martial artists enter the Jing Wu School in the midst of the funeral of the Chinese master, Huo Yuanjia. They enter whilst a senior Chinese is giving an impassioned oration about what the Jing Wu School ‘stands for’. The threnody is, of course, also a ‘pep talk’ or rallying call which is insisting that even though their institution has been struck hard by the death of their founder and master, his demise does not signal the demise of the institution, for Huo Yuanjia has taught them all well enough to ensure that the institution might continue, by following the principles he sought to inculcate. In other words, the threnody is also very much an appeal for continuity during a tense and difficult moment of crossing-over: the transition/translation from one cultural moment and institutional order to another. That is, at this point, upon the death of the master, what comes to the fore are urgent matters of transmission and tradition. What need to be transmitted now, more than ever, are the means to maintain stability. The tradition needs to be reiterated, reasserted, taking the form of emphatic words, in order to clarify what is to survive.

Immediately upon completing this (teleiopoietic) appeal, an entourage from the Japanese School arrive. They arrive in a literal hiatus: a moment’s silence during the service. They show great disrespect, offer a personally, ethnically and nationally insulting gift, and throw down physical challenges. This is all articulated by Mr Wu, the translator. Chen Zhen (Bruce Lee) wishes to pick up the gauntlet and to fight the challengers, but is verbally restrained by his senior. He has to be called to order by his superior. What is clear is that it is only because of the material presence of hierarchy, tradition and convention – in terms of the gaze and commands of his superiors – that Chen Zhen will restrain himself. We feel sure that, left to his own devices, Chen would have responded to the challenge. And the next scene confirms this when Chen enters the Japanese Bushido School alone, walks into the middle of their martial arts class and beats them all single-handedly. But, before this, Chen and all of the Chinese have to suffer the humiliation of respecting another tradition: the order and decorum of the funeral.

After this point, all hell breaks loose. Other than by focusing on the dimension of the Japanese aggression, one way to represent the reasons for the strife and pain experienced by all of the Chinese throughout Fist of Fury (although there are, of course, many different ways to represent this, depending on one’s concerns) devolves on the splitting of a stabilised entity that was putatively one into more (and less) than one, caused by two interpretations. The death of the univocal and unequivocal master is always a moment of great institutional jeopardy anyway. The eulogy given in Fist of Fury is an attempt to pre-empt problems of transmission and ward off a crisis. But then the Japanese agitators enter and provoke a very real crisis that demands to be answered there and then.

Chen Zhen, like many of the students, evidently wants to respond to the martial challenge. Certainly, there is an element of decorum and obligation to throwing down and picking up martial gauntlets in the world of martial arts schools. However, a funeral seems hardly the time or the place to start a fight. This is obviously the senior members’ interpretation: preserve this decorum. But, to the younger students, given that the Japanese have so completely transgressed the decorum of the official funeral ceremony already by offering the offensive ‘gift’, throwing down insults and offering to fight any of them there and then, the weight of obligation is taken to fall on answering the challenge. Yet, as Captain puts it after the Japanese leave, upon being asked why he would not let the Chinese fight: he ‘wanted to’ but ‘teacher taught us that we shouldn’t’.

The reasons for stoicism given repeatedly by Captain throughout the first half of Fist of Fury always involve insisting that the Jing Wu School studies martial arts to make healthy bodies, minds and subjects that will be available to serve the Chinese nation should they ever be required. To his mind, at first, the Japanese aggression is merely inter-school feuding; so rising to their challenge would be to abuse their skills, training, ethos and lineage. Little does he know – little do any of the Chinese know – how wrong this interpretation is. Captain is wrong to dismiss the ethnically inflected inter-school challenge as mere trouble. But by the time he realises that the challenge is actually a challenge to their very presence within the Japanese-controlled section of the international settlement of Shanghai it is too late. In other words, Captain imagines that fidelity to the nation-building ethos of the Jing Wu School involves ignoring this ethnically-inflected aggression and waiting for something like an official Chinese state call to arms.

Chen Zhen interprets things somewhat differently. According to his interpretation, propriety demands that the rude challenge be answered. After being reined in by his superior, Captain, Chen takes the first opportunity the next day to execute an exemplary demonstration of propriety in martial arts etiquette: he walks alone into the Japanese School, whilst they are all training, says he is returning the ‘gift’ and that he is prepared to fight ‘any Japanese here’.

Thus, the emergence of a challenge to the already precarious status of the Jing Wu institution in a moment of transition/translation introduces a disunity which causes the institution to fracture. The master constituted the embodiment of the actuality of the institution, its direction and its principles, and so could have decided unequivocally. His death transforms him into the absent spectral figure or ‘spirit’ in terms of which interpretations and decisions are to be made. Because operating with fidelity to his terms or ethos in his absence demands an engagement with the terms he used, then, because he is not there to take their decisions for them, and because analysing the key terms inevitably reveals them to be ambiguous, ambivalent and uncertain, then conflicting and contradictory interpretations inevitably enter. What has literally entered to precipitate such a crisis is the inevitability of translation.

QUEER LEE

The translator clearly requires some attention. In Fist of Fury the translator adopts Western sartorial norms and works for the powerful Japanese presence that exerts such a considerable force in the international settlement in Shanghai. He enables communication between the Chinese and the Japanese institutions, and also sabotages one institution’s development at a particularly fraught moment – the funeral, the moment of transition/translation/passing over from one generation to the next, from the stability of the founding master’s presence and protection to the uncertain leadership of his multiple senior students. As it turns out, the translator in fact precipitated this unnatural crisis in the first place – installing spies and transmitting assassination orders. The translator is a pervertor. So, it is unsurprising that he has been constructed as certainly ‘queer’ and probably gay.

In this largely erotically-neutered film, Mr Hu’s sexuality is unclear. All that is clear is that he is creepy and effeminate. But if we are in any doubt about his sexuality, this same character, played by the same actor, was to return in Lee’s next film, Way of the Dragon (1972). Way of the Dragon is a film that Lee himself directed and in which he plays Tang Lung, a mainland/New Territories Hong Kong martial artist who flies to Rome to help his friend’s niece when her restaurant business is threatened by a veritably multicultural, interracial ‘mafia’ gang. The Chinese title of Way of the Dragon (Meng Long Guo Jiang) is rendered literally as something like ‘the fierce dragon crosses the river’, which refers to travel and migration, and hence to the diasporic Chinese crossing over to Europe.

In both Fist of Fury and Way of the Dragon, the same actor plays virtually the same character. However, in the European location of Way of the Dragon, we have crossed over from ‘traditional’ China to ‘modern’ Europe. So the translator becomes blatantly gay: wearing flamboyant clothing and behaving flirtatiously with Lee’s character, Tang Lung (see Chan 2000). In the later film, the translator is queerness unleashed. But the point to be emphasised here is that essentially the same reiterated rendering of the translator as creepy and queer is central to both films – in much the same way that Judas is central to the story of Jesus. If it were not for him, none of this would be possible, but as a contact zone or agency of communication and movement, he is responsible for warping and perverting things. In both films, the translator enters at a moment or situation of crossing over, and signals the break, the end of stability, the severance from paternal protection, from tradition. ‘And yet’, as Chow has noted, ‘the word tradition itself, linked in its roots to translation and betrayal, has to do with handing over. Tradition itself is nothing if it is not a transmission. How is tradition to be transmitted, to be passed on, if not through translation?’ (1995: 183)

Chow’s championing of such translation notwithstanding, the answer to her rhetorical question (‘how is tradition to be transmitted, to be passed on, if not through translation?’) as (if) it is given by both films is not that ‘tradition ought to be transmitted through translation’, but rather that ‘tradition ought to be transmitted through monolingualism and monoculturalism’. The problem – and it is presented as a problem in the films – is that culture does not stay ‘mono’. Its authorities want it to be; its institutions try to make it stay so; but it cannot. Even the most pure repetition is never pure, but is rather impure – a reiteration which differs and alters, introducing alterity, however slightly: re-itera, as Derrida alerted us. Basically, that is, one does not ‘need’ an insidious translator to pervert things. The unstoppable flow of transnational popular cultural products, commodities and practices, mass media sounds and images, and filmic texts does the job of the pervertor quite well enough. And surely far more cross-cultural encounters, exchanges and transactions are enacted by way of mass commodities than by way of dry hermeneutic or linguistic translation.

Given this plague of contact zones, Chow argues: ‘cultural translation can no longer be thought of simply in linguistic terms, as the translation between Western and Eastern verbal languages alone’ (1995: 196–7). Rather, she proposes, ‘cultural translation needs to be rethought as the co-temporal exchange and contention between different social groups deploying different sign systems that may not be synthesizable to one particular model of language or representation’ (1995: 197). As such:

Considerations of the translation of or between cultures […] have to move beyond verbal and literary languages to include events of the media such as radio, film, television, video, pop music, and so forth, without writing such events off as mere examples of mass indoctrination. Conversely, the media, as the loci of cultural translation, can now be seen as what helps to weaken the (literary, philosophical, and epistemological) foundations of Western domination and what makes the encounter between cultures a fluid and open-ended experience. (Ibid.)

Once again, it strikes me as important to reiterate at this point that although the encounters of cultural translation may be fluid and open-ended, the treatment of such encounters by academics and cultural commentators is far from fluid and open-ended. On the contrary, such treatment seems rigid; overdetermined, even. Translatory encounters of or between cultures are, in fact, regularly treated by academics and cultural commentators in a manner akin to the way the translator is treated in these films: ridiculed, reviled, rejected and killed – but too late. Such films, whether putatively lowbrow like these or supposedly highbrow like those of Zhang Yimou or Ang Lee are often regarded with disdain: as not ‘real’, not ‘true’ or not ‘faithful’ translations of that fantastic phantasmatic essentialised entity known as ‘China’. Chow writes:

Using contemporary Chinese cinema as a case in point, I think the criticism (by some Chinese audiences) that Zhang and his contemporaries ‘pander to the tastes of the foreign devil’ can itself be recast by way of our conventional assumptions about translation. The ‘original’ here is not a language in the strict linguistic sense but rather ‘China’ – ‘China’ as the sum total of the history and culture of a people; ‘China’ as a content, a core meaning that exists ‘prior to’ film. When critics say that Zhang’s films lack depth, what they mean is that the language/vehicle in which he renders ‘China’ is a poor translation, a translation that does not give the truth about ‘China’. For such critics, the film medium, precisely because it is so ‘superficial’ – that is, organized around surfaces – mystifies and thus distorts China’s authenticity. What is implicitly assumed in their judgment is not simply the untranslatability of the ‘original’ but that translation is a unidirectional, one-way process. It is assumed that translation means a movement from the ‘original’ to the language of ‘translation’ but not vice versa; it is assumed that the value of translation is derived solely from the ‘original,’ which is the authenticator of itself and of its subsequent versions. Of the ‘translation’, a tyrannical demand is made: the translation must perform its task of conveying the ‘original’ without leaving its own traces; the ‘originality of translation’ must lie ‘in self-effacement, a vanishing act’. (1995: 184)

Such texts are regularly written off as trivial and trivialising, commodified, Orientalist, unfaithful, secondary, derived, warped, warping, and so on. But as the works of thinkers like Chow have proposed, such responses to migrant texts like these might be (essentialised as) essentialist. Nevertheless, asks Chow: ‘can we theorize translation between cultures without somehow valorizing some “original”?’; moreover, ‘can we theorize translation between cultures in a manner that does not implicitly turn translation into an interpretation toward depth, toward “profound meaning”?’ (1995: 192). She asks these questions not simply in the spirit of the post-structuralist, deconstructive or anti-essentialist problematisation of ‘essences’ and fixed/stable identities; but rather because of the extent to which many theories of translation focus exclusively on the ‘intralingual and interlingual dimensions of translation’ (ibid.) and hence miss the cultural significance ‘of intersemiotic practices, of translating from one sign system to another’ (1995: 193). Her answer urges us to rethink translation by way of mass commodities, whose ‘transmissibility’ arguably arises ‘in opposition to … “truth”’ (1995: 199) in the context of a ‘sickness of tradition’. This ‘sickness’ is actually constitutive of transmissibility, suggests Chow.

To this I would add: this sickness is queer. In constructing the translator as a traitor and therefore as queer, both of these films cling to tradition – a tradition that seems universal and seems to need no translating. If we ask of this tradition, ‘Are you Chinese?’ the answer must be: yes, but no; yes and no.8 And if we ask ‘Just what is the point of this?’ one answer must be that it points to a queer relation – but a clear relation – between translation and queering. About which much could be said. But the point I want to emphasise here is that the primary field of ‘translation between cultures’, through their twisting, turning, concatenation, warping and ‘queering’ is, of course, that supposed ‘realm’ (which of course really should be rather better understood as the condition) called mass or popular culture.

As we have seen, Chow’s contention is that ‘there are multiple reasons why a consideration of mass culture is crucial to cultural translation’; to her mind, ‘the predominant one’ is to examine ‘that asymmetry of power relations between the “first” and the “third” worlds’ (1995: 193). However, as she continues immediately, ‘critiquing the great disparity between Europe and the rest of the world means not simply a deconstruction of Europe as origin or simply a restitution of the origin that is Europe’s others but a thorough dismantling of both the notion of origin and the notion of alterity as we know them today’ (1995: 193–4). In Bruce Lee films, of course – in a manner akin to the arguments of the critics who regard popular filmic representations as betrayals of ‘China’ – the ‘origin’ is avowedly not Europe, but ‘China’ – the spectral, haunting, ‘absent presence’, the evocation (or illusion-allusion) of ‘China’. From this perspective, there are two alterities: the ‘simple’ alterity of the enemy, and the ‘double’ alterity of the translator. In Fist of Fury, alterity seems unequivocal: an enemy (the colonisers – Japan in particular). When the Hong Kong films cross over to Europe or America, for Way of the Dragon, however, origin and alterity become more complicated.

EURO-AMERICAN LEE

In Lee’s first martial arts film, The Big Boss (1971), he plays a migrant Chinese worker in Thailand – a country boy cum migrant proletarian whose enemy is a foreign capitalist/criminal. In Fist of Fury, when hiding from the authorities, Chen Zhen’s peers emphasise that even though they cannot find him he surely cannot be far away because he is a country boy who does not know Shanghai. In Way of the Dragon, in Italy, Lee’s character rejoices in the fact that he comes not from urban Hong Kong Island but from the rural mainland New Territories. Dragged grudgingly on a tour of the sites of Rome, he is evidently rather under-whelmed. In the sole scene of Fist of Fury that was filmed outdoors, at the entrance to a segregated public park, Lee’s character evidently only wants to go into the park because, being Chinese, he is not allowed – because China has been provincialised: a turban-wearing, English-speaking Indian official at the gate directs Lee’s attention to a sign which says ‘No Chinese and Dogs Allowed’.

In other words, all of the injustices in Lee’s Hong Kong films are organised along ethnonationalist and class lines, and the notion of the origin in these films is the idea of mainland China. This idea in itself provincialises the various locations of each of the films. All of the places that are ‘not China’ are just vaguely ‘somewhere else’, and that elsewhere is ‘bad’ (or at least not very good) because, wherever it is, it is ‘not China’ – not the free, proud, strong, independent ‘imagined community’ China ‘to come’.

Of course, in sharing this tendency, these films construct a Chinese identity that is also based on actively celebrating or enjoying being what Chow calls ‘the West’s “primitive others”’ (1995: 194). (In other words, actively involved in a complex dialectical identification akin to Hegel’s (1977) much (re)theorised dialectic of Lord and Bondsman, within which each identity depends on (is constituted and compromised by) the other’s (mis)recognition.) To this extent these films may easily seem, in Chow’s words, to be ‘equally caught up in the generalized atmosphere of unequal power distribution and [to be] actively (re)producing within themselves the structures of domination and hierarchy that are as typical of non-European cultural histories as they are of European imperialism’ (ibid.). Yet, at the same time, they are also and nevertheless (to use Dipesh Chakrabarty’s term) actively involved in ‘provincializing Europe’, albeit without any reciprocal (self-reflexive) problematisation of ‘China’ (see Chow 1995: 195).

However, it strikes me that such a problematisation was palpably embryonic and growing in many of Lee’s other works: in his TV roles, personal writings and interviews, Lee increasingly gestured to a postnationalist, liberal multiculturalist ideology; and it was perhaps ‘in the post’ at the time of his death in the form of his declared intentions for his unfinished film Game of Death. But even in his ‘early’ film, Way of the Dragon, even though it is certainly caught up in a degree of masochistic enjoyment of Chinese victimhood, the film arguably enacts what Chow’s proposed approach to film (‘as ethnography’) could construe as a significant discursive move. So it is with a brief – summary – consideration of this embryonic impulse that I would like to conclude this chapter.

The very first scenes of Way of the Dragon place Lee in the arrivals area of an airport in Rome. Lee is surrounded by white Westerners and is being stared at, implacably, unremittingly, and inscrutably by a middle-aged white woman. This lengthy, awkward and tense scene goes nowhere. The woman is eventually dragged away by a man who comes to meet her. It is followed immediately by an excruciatingly lengthy scene in which Lee’s character goes in search of food within the airport. First he approaches a child and asks ‘food?’, ‘eat?’, and then, pointing to his mouth, ‘eggs?’, whereupon the camera changes to the child’s point of view, showing a huge towering man looming over the child, pointing at his own mouth and making horrendous gurgling sounds. The child screams, and Lee’s Tang Lung hurries away. He soon stumbles across a restaurant, which he enters. Unable to make sense of the Italian menu, he jabs his finger confidently to more than half a dozen dishes – all of which turn out to be different kinds of soup. So Lee is presented with a ludicrous dinner of multiple bowls of soup, which he brazenly pretends he knew he had ordered.

These slow, clumsy and somewhat bizarre scenes could easily strike viewers, especially white Western viewers, as a peculiar way to begin a martial arts film – a film, it should be noted, that very soon opens out into extreme violence, murder, mortal treachery, and even a gladiatorial fight to the death in the Roman Coliseum. Beginning such a film with these rather torturous efforts at comedy seems to be a peculiar directorial decision.

However, there is something significant in the way that these opening scenes dramatise ethnic experience. The film shows us an ethnic ‘viewed object’. But it does so from a crucial point of view; one in which ‘“viewed object” is now looking at “viewing subject” looking’ (Chow 1995: 180–1). Thus, over twenty years before Chow proposed precisely such a twisting (or queering) of specular relations away from a simple subject/object diaeresis as the way to escape the deadlock of Western anthropology, ‘simple’ popular cultural artefacts like this film were already actively engaged in this deconstruction, in which Europe is not the viewing subject and Europe is not ‘the gaze’, and in which – as Way of the Dragon seems to be at pains to make plain – Europe is just some place in an increasingly fluid globality.

Europe never becomes origin or destination in the film. In fact Italy itself never really becomes much more than an airport lounge – a zone of indeterminacy, a contact zone; just some place or other, between origin A and destination B, C or D, or X, Y or Z. Lee left Hong Kong in the first place to help a diasporic working community. He flies to Europe. The Europeans cannot defeat him. Frustrated, they arrange to fly in ‘America’s best’. America’s best takes the form of ‘Colt’, a martial artist played by Chuck Norris. Colt flies in. His arrival is filmed from a low angle. He walks down from a jet plane, and towards the camera. A drum beat marks his every powerful step. As he approaches, what is more and more foregrounded is his crotch. When he reaches the camera, it is his crotch that comes to fill the entire screen and close the scene. And so it continues: as has been much remarked, Colt is all crotch, Lee is all lithe, striated torso. Their pre-fight warm-ups are more like foreplay; their fighting is more like love-making (see Chan 2000; Hunt 2003). But the film plays the standard semiotics of powerful masculinity; in other words, treading a fine line between emphasising heterornormativity and crossing over into outright homoeroticism. Hating the queer element is important in order to assert that this text itself is not of or for the queer; whilst all the time exemplifying the polymorphously perverse recombination, intermingling and reconstitution of cultures, provincialising and queering Europe. We will return to this in the next chapter.

notes