Over the years, Flash has acquired many new features, but at heart it's still an animation tool. The best way to learn Flash is to jump in and start drawing. So that's exactly what you'll do in this chapter. It starts with tips for planning your animation and then moves on to specific tools like the Pen, the Pencil, the Shape tool, the Line tool, and the Brush. You'll draw a simple picture and see how to use Flash to draw in different styles, from cartoons to mechanical drawings. Once you've created some drawings, you'll learn more about moving and arranging objects on the stage.

In the next chapter, you'll add a few more drawings and string them together to create a simple animation.

If you're just creating a simple banner ad, you probably already have a concept in mind and are itching to start drawing and animating. On the other hand, if you're creating a new feature for the Cartoon Network, then you need to think like a movie director. If you're creating a handheld or phone app or a rich Internet application (RIA), then you need to think like a graphic user interface (GUI) designer. Whatever you're producing, it pays to plan. In the case of an ad, what do you want your audience to do? What sales message will motivate it? If your goal is to entertain, then you need to think about how to tickle people's funny bones or how to move them emotionally. If the story is complicated, then you need to break it down into scenes and use the entire storyteller's toolkit to be effective. To learn some of the tricks of the storytelling trade, try the techniques animators and graphic novelists use. If you're designing an application, whether it's for a handheld device or a full-size web page, you need to think about the needs of the app's users. What do they want to do? What tools do they expect to use?

Drawing a single picture is relatively easy. But creating an effective animation—one that gets your message across, entertains people, or persuades them to take an action—takes a bit more up-front work. And not just because you have to generate dozens or even hundreds of pictures: You also have to decide how to order them, how to make them flow together, when (or if) to add text and audio, and so on. With its myriad controls, windows, and panels, Flash gives you all the tools you need to create a complex, professional animation, but the creativity comes from you. You can avoid pitfalls and wasted time by planning before you draw.

Say you want to produce a short animation to promote your company's great new gourmet coffee called Lotta Caffeina. You decide your animation would be perfect as a banner ad. Now, maybe you're not exactly the best artist since Leonardo da Vinci, so you want to keep it simple. Still, you need to get your point across—BUY OUR COFFEE!

Before you even turn on your computer (much less fire up Flash), pull out a sketch pad and a pencil and think about what you want your animation to look like.

For your very first drawing, you might imagine a closeup of a silly-looking face on a pillow, belonging to a guy obviously deep in slumber, eyes scrunched tight, mouth slack. Next to him is a basic bedside table, empty except for what appears to be a jangling alarm clock.

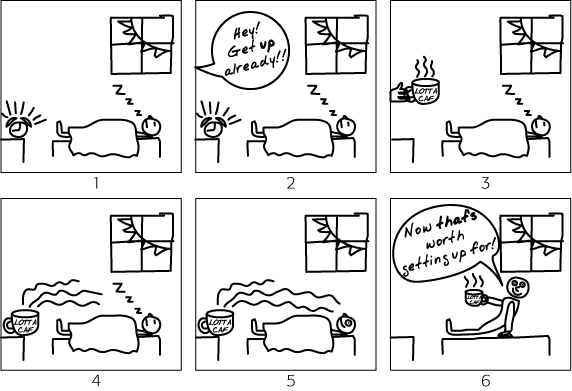

OK, now you've made a start. After you pat yourself on the back—and perhaps refuel your creativity with a grande-sized cup of your own product—it's time to plan and execute the frame-by-frame action. You do this by whipping out six quick pencil-and-paper sketches. When you finish, your sketch pad may look something like this:

The first sketch shows your initial idea—Mr. Comatose and his jangling alarm clock.

Sketch #2 is identical to the first, except for the conversation balloon on the left side of the frame, where capped text indicates that someone is yelling to your unconscious hero (who remains dead to the world).

In sketch #3, a disembodied hand appears at the left side of the drawing, placing a cup bearing the Lotta Caffeina logo on the bedside table next to Mr. Comatose.

Sketch #4 is almost identical to the second, except that the disembodied hand is now gone, and Mr. Comatose's nose has come to attention as he gets a whiff of the potent brew.

Sketch #5 shows a single eye open. Mr. Comatose's mouth has lost its slackness.

The last sketch shows a closeup of the man sipping from the cup, his eyes wide and sparkling, a smile on his lips, while a "thought bubble" tells viewers, "Now, that's worth getting up for!"

In the animation world, your series of quick sketches is called a storyboard.

Figure 2-1 shows a basic storyboard.

Creating your Flash animation will go more smoothly if you can answer these five basic questions:

What do you want to accomplish with this Flash creation? Give yourself a mission statement, just as if you were in one of those tedious business meetings. You want something like "Generate 1,000 hits for the Lotta Caffeina website" or "Create a 22-minute animation set on the planet Galactrix" or "Develop an iPhone app for movie lovers."

Who's your audience? Different types of people require different approaches. For example, kids love all the snazzy effects you can throw at them; adults aren't nearly as impressed by animation for animation's sake. The better sense you have of the people most likely to view your Flash creation, the better you can target your message and visual effects specifically to them.

What third-party content (if any) do you want to include? Content is the stuff that makes up your Flash animation: the images, text, video, and audio clips. Perhaps you want your animation to include only your own drawings, like the ones you'll learn how to create in this chapter. But if you want to add images or audio or video clips from another source, then you need to figure out where you're going to get them and how to get permission to use them. (Virtually anything you didn't create—a music clip, for example, or a short scene from a TV show or movie—is protected by copyright. Someone somewhere owns it, so you need to track down that someone, ask permission, and—depending on the content—pay a fee to use it. Chapter 11 lists several royalty-free, dirt-cheap sources of third-party content.)

How many frames is it going to take to put your idea together, and how do you want them to be ordered? For a simple banner ad, you're looking at anywhere from a handful of frames to around 50. A tutorial or product demonstration, on the other hand, can easily require 100, 200, or more frames. Whether you use storyboarding or just jot down a few notes to yourself, getting a feel for how many frames you'll need helps you estimate the time it's going to take to put your animation together.

How will you distribute it? In other words, what's your target platform? If you plan to put your animation up on a website, then you need to keep file size to a minimum so people with slow connections can see it; if you plan to make it available to hearing-impaired folks, then you need to include an alternative way to communicate the audio portion; if you're creating an animation you know will be played on a 100-inch monitor, then you need to draw large, bold graphics. Your target platform—the computer (or device) and audience most likely to view your project—always affects the way you develop your animation.